Abstract

Background

Several surgical reconstructive options are available to treat massive rotator cuff tears (MRCTs). The rotator cable has an important function and we evaluated the clinical result after arthroscopic reconstruction of the rotator cable with an autograft tendon.

Methods

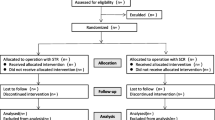

A prospective pilot study was performed with inclusion of four patients, average age of 64 years, with an irreparable MRCT. The patients underwent an arthroscopic reconstruction of the rotator cable with the use of the long head of biceps tendon autograft, except for one which was reconstructed with a hamstring tendon. Pre- and postsurgically, the Constant-Murley Score (CMS), Western Ontario Rotator Cuff Index (WORC), Simple Shoulder Test (SST), visual analog scale (VAS) scores, and an MRI was performed. Clinical results of the study group were compared with clinical results of comparable cohort of patients with a MRCT, treated non-operatively with physiotherapy.

Results

The CMS score increased after surgery in three of the four patients. The improvement of CMS score was comparable to the improvement of the CMS score encountered in a comparable cohort. The MRI at 12 months follow-up showed that the reconstructed rotator cable was disintegrated in all patients and the rotator cuff was detached and retracted.

Conclusions

In our pilot study, arthroscopic reconstruction of the rotator cable using a tendon autograft failed over time and showed no clinical benefit in comparison to the non-operative treatment with physiotherapy.

Trial registration

The regional Medical Ethical Committee (Zwolle) gave approval at 14th of October 2016 and assigned no. 16.06100.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Massive rotator cuff tears (MRCTs) are defined as cuff tears involving two or more cuff tendons or a retraction of ≥ 5cm [1]. Patients frequently present with pain and loss of function (pseudoparalysis), sometimes after minimal trauma. A MRCT can have a huge impact on daily life and eventually could lead to a cuff arthropathy. Variable success rates are seen after primary cuff repair in small-to-medium-sized tears with retear rates between 14 and 25% [2]. If the repair is successful and the cuff has healed after surgery, patients have a better outcome compared with patients after conservative or failed surgical therapy [3, 4]. MRCT defects cannot be easily closed, and there is a rate of retears reaching up to 94% [5, 6]. Several surgical reconstructive options for MRCTs are available, each with its own reported advantages and complications [7]. Patches and grafts are expensive and can lead to rejection. Another technique is superior capsular reconstruction to treat these lesions [8]. Initial results for reconstruction of the superior capsule seem promising, although long-term results are awaited. Reversed shoulder arthroplasties and tendon transfers are alternative options, yet these are major surgeries with considerable morbidity [9].

A tenotomy or tenodesis of the long head of the biceps tendon is often performed as part of rotator cuff surgery. This offers the possibility of using the biceps tendon as a graft. Different studies used this tendon as a free graft or leaving the distal or proximal attachment intact, reporting significant improvement of function [10]. In the native shoulder, the rotator cable is a thickening in the rotator cuff that serves as a primary load-bearing structure between the rotator cuff and the humerus and functions as a tension bridge. Recent studies show the clinical and biomechanical importance of this structure [11, 12].

We developed a technique to treat MRCTs by reconstructing the rotator cable with a long head of biceps tendon autograft [13]. But a hamstring tendon is also suitable. This technique represents a reconstruction with several advantages: use of an autograft, ease of harvesting, no graft reactions, fixation of cuff to reconstructed rotator cable instead of footprint, and potential prevention of cuff arthropathy.

The aim of this study is to evaluate the clinical and radiological result after arthroscopic reconstruction of the rotator cuff cable with an autograft tendon in patients with irreparable massive rotator cuff tears.

Methods

Indications

A prospective pilot study was conducted between February and December 2016. Patients aged 50 or older diagnosed with an irreparable MRCT (2–3 tendon tears, Patte stage 3 retraction), based on MRI, were included [14]. At physical examination, all had impaired abduction and decreased strength of the infraspinatus and supraspinatus muscles. All had undergone conservative treatment of at least 3 months consisting of physiotherapy and/or subacromial injections, without the expected effect. Exclusion criteria were as follows: symptomatic glenohumeral or acromioclavicular osteoarthritis, rheumatoid arthritis, previous surgery on the same shoulder or arm, and cognitive or linguistic issues. After 1 year of inclusion, the clinical results of this new operative technique were evaluated. Four patients were included in this year. The local institutional review board approved this study (no. 16.06100), and all patients gave informed consent. The study was done according to the ethical standards of the 1964 Helsinki Declaration and its later amendments.

Primary outcome was the Constant-Murley Score (CMS). We looked secondarily at the Simple Shoulder Test (SST) [15], Western Ontario Rotator Cuff Index (WORC) [16], and visual analog scale (VAS) [17] on pain, disability, and patient satisfaction. Scores were taken preoperatively at 3, 6, and 12 months.

Prior to surgery and 12 months postoperatively, an MRI scan was performed and the rotator cuff retraction and fatty infiltration were graded with Patte and Fuchs scores [14, 18]. Extension of the tear and number of torn tendons were also noted. Evaluation was done by an experienced musculoskeletal radiologist.

The results were compared with a cohort of patients with a MRCT, Patte stage 3, treated non-operatively with physiotherapy. These patients were selected from a previous RCT performed at our institution, comparing surgical rotator cuff repair with conservative treatment for degenerative rotator cuff tears [3]. The conservative protocol has been described previously, and scores were collected with the same interval during 12 months [3]. From the patients treated non-operatively with physiotherapy, eight patients with a MRCT had a Patte stage 3 and were included; in five patients, all follow-up data were available and used as a comparable cohort.

Surgical procedure

This technique was first tested on cadavers to assess feasibility and detect any pitfalls. All surgeries were performed by one shoulder surgeon (CK). The surgical technique was extensively described in a previous report [13].

Patients were operated in the beach chair position after an interscalene block of the brachial plexus and general anesthesia. The standard procedure started by introducing the scope through the posterior portal. After confirming the diagnosis of MRCT, the intra-articular portion of the biceps was tenotomized just distally of the insertion on the superior labrum. Next, the tendon was harvested through a small anterolateral incision at the bicipital sulcus. In case this tendon was degenerated, a hamstring autograft was used.

Cuff preparation and mobilization

The subacromial space was inspected, and a bursectomy was performed through a lateral portal to create a clear view of the remnants of the rotator cuff. An extensive release of the cuff was performed subacromially and between the cuff and the superior labrum with close attention to the suprascapular nerve.

Biceps graft fixation

The tendon was prepared and marked, with 20 mm tendon left on each side to be inserted into the humeral bone with biotenodesis screws (tenodesis biocomposite anchors, 7 × 19.1 mm) (Fig. 1). An additional posterolateral portal was made to drill a hole for the posterior screw with a diameter equal to the tendon, approximately in the middle of the footprint of the infraspinatus on the greater tubercle. With the biceps autograft under tension, this posterior screw was tightly inserted until the pre-marked portion of the biceps tendon (Fig. 2). After positioning of the graft, a drill hole was made in the bicipital groove at the superior part of the lesser tubercle.

Final rotator cuff repair to rotator cable

The final step was the actual cuff repair. The sutures were passed transversely around and through the biceps tendon autograft (Fig. 3). The medial part of the sutures was passed through the infraspinatus and supraspinatus tendons with a suture-passing device. An average of five sutures were needed in order to bring the rotator cuff to the tendon autograft.

Postoperative protocol

The shoulder was immobilized for 6 weeks, during which passive movements were allowed under the guidance of a physiotherapist. Afterwards, further guided active mobilization was started.

Statistical analysis

Patient characteristics are expressed descriptively. The SPSS statistical software (version 20.0; IBM, Armonk, NY, USA) was used for data compilation and statistical analyses. Only descriptive statistics were considered suitable considering the number of patients in each group. Because of the pilot study design, a sample size calculation was not feasible.

Results

A total of four patients were included in this study. Patient characteristics are depicted in Table 1. Mean age of the study population was 64 years (61–67 years), all with their dominant side affected, and one was a smoker. In all patients, a massive cuff tear of the supraspinatus and infraspinatus tendon was present with a Patte stage 3 retraction; in one patient, a partial subscapularis tendon tear was found and repaired. Fatty infiltration on the postoperative MRI scan differed between Fuchs stages 2 to 3 on the preoperative MRI. One patient discontinued the study 9 months after surgery because of lack of postsurgical improvement, and a reversed shoulder prosthesis was inserted. The final scores of this patient were considered as an endpoint.

For comparison, a similar group of patients who were treated conservatively was selected. This comparable cohort consisted of five patients, mean age was 65 years (57–72 years), and more women were present in this group. All patients had a massive cuff tear of the supraspinatus and infraspinatus tendon with a Patte stage 3 retraction; in one patient only, the supraspinatus was torn and was treated using physiotherapy.

Table 2 shows the clinical outcome of the study group after surgery and the group treated with physiotherapy. Total CMS score increased significantly after surgery in three of the four patients, with a mean improvement of 26.4 points after 12 months (p = 0.023) (Fig. 4). The WORC index, depicted as a percentage of a normal score, showed a mean improvement of 5 points (p = 0.191). SST, VAS pain, VAS disability, and VAS satisfaction scores also improved in these patients. All except for patient 4 showed improvement on the scores. In all patients, an MRI was performed 12 months after surgery. In all patients, the reconstructed rotator cable had disintegrated and the rotator cuff was detached from the rotator cable and retracted. Fatty infiltration of the infraspinatus muscle before surgery was grade 2 in two patients and grade 3 in two patients. At follow-up, all patients had fatty infiltration of the infraspinatus muscle grade 3 on MRI. The partial subscapular repair was healed on MRI in patient 3. None of the patients had any signs of osteoarthritis on MRI before or after surgery.

Compared with the patients who were treated conservatively, the CMS and VAS pain and disability scores of the surgical group were similar before treatment and at 12 months follow-up. At 3 and 6 months after surgery, the clinical results were inferior to the non-operative group.

Discussion

Clinical and radiological results after tendon autograft for reconstruction of the rotator cable were collected in four patients with a MRCT. On the MRI scan, 1 year after surgery, the rotator cable reconstruction disintegrated and failed; clinical results were not superior to the results after non-operative treatment with physiotherapy. Because of disappointing preliminary results and a vanishing reconstructed rotator cable on MRI during 1 year of inclusion, no further patients were included. When developing this new surgical procedure, we hypothesized that the procedure might have several advantages. This technique results in a biomechanical reconstruction leading to transporting force couples from the rotator cuff to the humeral head. As the remaining rotator cuff was attached to the rotator cable and not to the footprint, we were able to reattach the rotator cuff to the cable in irreparable cuff tears. With this technique, tension on the massive cuff tear gap was minimized by medializing the new rotator cable. The technique represents a reconstruction with the use of an autograft. The biceps tendon is easy to harvest and gives no graft reactions. In other studies, the biceps tendon was used as an augmentation of the rotator cuff with good clinical results. Although we observed improved clinical results in three out of four patients 1 year after surgery with the CMS and WORC exceeding the minimal important clinical difference of 10.4 points [19] and 282.6 points [20] respectively, MRI showed failure of the reconstructed rotator cable in all patients.

While performing the index operation, we used margin convergence to close the cuff partially to the reconstructed rotator cable, but on MRI scan at follow-up, the cuff was re-torn and retracted compared with the preoperative situation. The improvement in pain and function could not be attributed to the reconstruction of the rotator cable as this construct failed over time [21]. The clinical improvement over time in the surgical group was similar to the improvement noted in the control group, treated non-operatively with physiotherapy. In two randomized controlled studies about cuff repair versus conservative treatment of degenerative rotator cuff tears, good clinical improvement was also found after conservative treatment. These studies showed a mean improvement of the CMS of 16.8 points after 1 year [3] and 18.4 points after 2 years [22] following conservative treatment. In both studies, this was not significantly different from the surgically treated patients. In our control group, a mean improvement of the CMS of 19.1 points was found after 1 year.

The rotator cuff showed fatty infiltration (grade 3 in two out of four patients). This may have resulted in low healing capacity and eventually a detachment of the rotator cuff from the reconstructed rotator cable on the control MRI. Previous studies also show that this is a predictor for worse outcomes in cuff repairs [23], even in cases of successful repair [24]. Reconstruction of the rotator cable failed over time in all patients. The biceps tendon may have been degenerative, thus preventing ingrowth, although histological analyses show that a degenerated biceps tendon is still rich in collagen [25]. In one patient, a hamstring graft was used because of a missing long head of biceps during surgery. This may be a bias confounding the outcome. The study group is small and consisted only of four patients. In our study protocol, we decided to include patients for this new technique for 1 year, and then evaluate the clinical and radiological results. Because the construction failed in all patients, we decided to end this pilot study. There is a possibility that this technique might be successful in some patients when a larger group of patients would be operated. Comparing the results of our study with other studies using a biceps tendon graft for rotator cuff repair, a superior outcome was found when the biceps tendon was used for augmentation with an improvement of 44.1 points on the CMS by Cho et al. [26]. Also, the long-term outcome scores of the latissimus dorsi transfer as treatment for massive rotator cuff tears were better, with an increase of 27 points on the CMS [27].

Treating MRCTs remains a significant challenge for the clinicians. Several surgical options are available for patients with a MRCT if conservative treatment fail: debridement, long head of biceps tenotomy, partial repair, rotator cuff advancement, bridging graft repair, superior capsular reconstruction, subacromial spacer, and reverse total shoulder arthroplasty. The variability in patient characteristics, co-interventions, outcome reporting, and length of follow-up in studies on MRCTs complicates sound comparison of treatments [28]. Joint preserving procedures are preferably used in young patients; in the older population, reversed shoulder arthroplasty or maybe the subacromial balloon spacer might be indicated. The superior capsular reconstruction has become a popular surgical technique. The short-term results of superior capsular reconstruction show consistent improvement in shoulder functionality and pain reduction. However, on longer follow-up, decreased acromiohumeral intervals indicate dermal allograft elongation and persistent superior migration of the humerus [29]. Placement of the subacromial balloon spacer is a minimally invasive, technically simple procedure with favorable patient-reported outcomes at limited short-term follow-up. However, inherent methodological limitations and patient heterogeneity between studies using the subacromial spacer may impair the ability to fully characterize the long-term efficacy, particularly relative to other potential surgical options [30, 31].

Conclusions

In conclusion, the arthroscopic reconstruction of the rotator cable using a tendon autograft failed over time in this pilot study, and showed no clinical benefit in comparison with the non-operative treatment with physiotherapy in patients with a MRCT. We therefore cannot recommend using this surgical procedure to treat patients with a massive rotator cuff tear.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- CMS:

-

Constant-Murley Score

- MRCT:

-

Massive rotator cuff tear

- MRI:

-

Magnetic resonance imaging

- SST:

-

Simple Shoulder Test

- VAS:

-

Visual analog scale

- WORC:

-

Western Ontario Rotator Cuff

References

Lädermann A, Denard PJ, Collin P. Massive rotator cuff tears: definition and treatment. Int Orthop. 2009;39(12):2403–14.

Millett PJ, Warth RJ, Dornan GJ, et al. Clinical and structural outcomes after arthroscopic single-row versus double-row rotator cuff repair: a systematic review and meta-analysis of level I randomized clinical trials. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2014;23:586–97.

Lambers Heerspink FO, van Raay JJ, Koorevaar RC, et al. Comparing surgical repair with conservative treatment for degenerative rotator cuff tears: a randomized controlled trial. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2015;24:1274–81.

Yang J Jr, Robbins M, Reilly J, et al. The clinical effect of a rotator cuff retear: a meta-analysis of arthroscopic single-row and double-row repairs. Am J Sports Med. 2017;45:733–41.

Galatz LM, Ball CM, Teefey SA, et al. The outcome and repair integrity of completely arthroscopically repaired large and massive rotator cuff tears. J Bone Joint Surg. 2004;86(2):219–24.

Hein J, Reilly JM, Chae J, et al. Retear rates after arthroscopic single-row, double-row, and suture bridge rotator cuff repair at a minimum of 1 year of imaging follow-up: a systematic review. Arthroscopy. 2015;31:2274–81.

Steinhaus ME, Makhni EC, Cole BJ, et al. Outcomes after patch use in rotator cuff repair. Arthroscopy. 2016;32(8):1676–90.

Pennington WT, Bartz BA, Pauli JM, et al. Arthroscopic superior capsular reconstruction with acellular dermal allograft for the treatment of massive irreparable rotator cuff tears: short-term clinical outcomes and the radiographic parameter of superior capsular distance. Arthroscopy. 2018;34:764–73.

Deprés-tremblay G, Chevrier A, Snow M, et al. Rotator cuff repair: a review of surgical techniques, animal models, and new technologies under development. J Shoulder Elb Surg. 2016;25(12):2078–85.

Veen EJ, Stevens M, Diercks RL. Biceps autograft augmentation for rotator cuff repair: a systematic review. Arthroscopy. 2018;34:1297–305.

Mesiha MM, Derwin KA, Sibole SC, et al. The biomechanical relevance of anterior rotator cuff cable tears in a cadaveric shoulder model. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2013;95:1817–24.

Rahu M, Kolts I, Põldoja E, et al. Rotator cuff tendon connections with the rotator cable. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2017;25:2047–50.

Veen EJ, Koorevaar CT, Diercks RL. Using the long head of biceps tendon autograft as an anatomical reconstruction of the rotator cable: an arthroscopic technique for patients with massive rotator cuff tears. Arthrosc Tech. 2018:e699–703.

Patte D. Classification of rotator cuff lesions. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1990;254:81–6.

Lippitt SB, Harryman DT, Matsen FA. The shoulder: a balance of mobility and stability. Rosemont: American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons; 1993. p. p545–59.

Kirkley A, Alvarez C, Griffin S. The development and evaluation of a disease-specific quality-of-life questionnaire for disorders of the rotator cuff: the Western Ontario Rotator Cuff Index. Clin J Sport Med. 2003;13(2):84–92.

Price DD, McGrath PA, Rafii A, et al. The validation of visual analogue scales as ratio scale measures for chronic and experimental pain. Pain. 1983;17(1):45–56.

Fuchs B, Weishaupt D, Zanetti M, Hodler J, Gerber C. Fatty degeneration of the muscles of the rotator cuff: assessment by computed tomography versus magnetic resonance imaging. J Shoulder Elb Surg. 1999;8(6):599–605.

Kukkonen J, Kauko T, Vahlberg T, et al. Investigating minimal clinically important difference for constant score in patients undergoing rotator cuff surgery. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2013;22:1650–5.

Gagnier JJ, Robbins C, Bedi A, et al. Establishing minimally important differences for the American Shoulder and Elbow Surgeons score and the Western Ontario Rotator Cuff Index in patients with full-thickness rotator cuff tears. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2018;27:e166.

Burkhart SS. Reconciling the paradox of rotator cuff repair versus debridement: a unified biomechanical rationale for the treatment of rotator cuff tears. Arthroscopy. 1994;10(1):4–19.

Kukkonen J, Joukainen A, Lehtinen J, et al. Treatment of non-traumatic rotator cuff tears: a randomised controlled trial with one-year clinical results. Bone Joint J. 2014;97:1729–37.

McElvany MD, McGoldrick E, Gee AO, et al. Rotator cuff repair: published evidence on factors associated with repair integrity and clinical outcome. Am J Sports Med. 2015;43:491–500.

Gladstone JN, Bishop JY, Lo IK, et al. Fatty infiltration and atrophy of the rotator cuff do not improve after rotator cuff repair and correlate with poor functional outcome. Am J Sports Med. 2007;35:719–28.

Mazzocca AD, McCarthy MBR, Ledgard FA, et al. Histomorphologic changes of the long head of the biceps tendon in common shoulder pathologies. Arthroscopy. 2013;29:972–81.

Cho NS, Yi JW, Rhee YG. Arthroscopic biceps augmentation for avoiding undue tension in repair of massive rotator cuff tears. Arthroscopy. 2009;25(2):183–91.

El-Azab HM, Rott O, Irlenbusch U. Long-term follow-up after latissimus dorsi transfer for irreparable posterosuperior rotator cuff tears. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2015;97:462–9.

Kooistra B, Gurnani N, Weening A, van den Bekerom M, van Deurzen D. Low level of evidence for all treatment modalities for irreparable posterosuperior rotator cuff tears. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2019;27(12):4038–48. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00167-019-05710-0 Epub 2019 Sep 18.

Zastrow RK, London DA, Parsons BO, Cagle PJ. Superior capsule reconstruction for irreparable rotator cuff tears: a systematic review. Arthroscopy. 2019;35(8):2525–2534.e1. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.arthro.2019.02.053.

Malahias MA, Brilakis E, Avramidis G, Antonogiannakis E. Satisfactory mid-term outcome of subacromial balloon spacer for the treatment of irreparable rotator cuff tears. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2019. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00167-019-05485-4.4.

Stewart RK, Kaplin L, Parada SA, Graves BR, Verma NN, Waterman BR. Outcomes of subacromial balloon spacer implantation for massive and irreparable rotator cuff tears: a systematic review. Orthop J Sports Med. 2019;7(10):2325967119875717. https://doi.org/10.1177/2325967119875717 eCollection 2019 Oct.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank O.F.O Lambers Heerspink for his help with the database.

Funding

None

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors have made substantial contributions to the conception and design, acquisition of data, and analysis and interpretation. All authors have been involved in drafting the manuscript or revising it critically for important intellectual content. All authors have given final approval of the version to be published. All authors agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The regional Medical Ethical Committee (Zwolle) gave approval at 14th of October 2016 and assigned No. 16.06100. All patients gave their informed consent.

Consent for publication

Not applicable

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Veen, E.J.D., Diercks, R.L., Landman, E.B.M. et al. The results of using a tendon autograft as a new rotator cable for patients with a massive rotator cuff tear: a technical note and comparative outcome analysis. J Orthop Surg Res 15, 47 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13018-020-1568-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13018-020-1568-0