Abstract

Background

Acute appendicitis (AA) is the most common surgical disease, and appendectomy is the treatment of choice in the majority of cases. A correct diagnosis is key for decreasing the negative appendectomy rate. The management can become difficult in case of complicated appendicitis. The aim of this study is to describe the worldwide clinical and diagnostic work-up and management of AA in surgical departments.

Methods

This prospective multicenter observational study was performed in 116 worldwide surgical departments from 44 countries over a 6-month period (April 1, 2016–September 30, 2016). All consecutive patients admitted to surgical departments with a clinical diagnosis of AA were included in the study.

Results

A total of 4282 patients were enrolled in the POSAW study, 1928 (45%) women and 2354 (55%) men, with a median age of 29 years. Nine hundred and seven (21.2%) patients underwent an abdominal CT scan, 1856 (43.3%) patients an US, and 285 (6.7%) patients both CT scan and US. A total of 4097 (95.7%) patients underwent surgery; 1809 (42.2%) underwent open appendectomy and 2215 (51.7%) had laparoscopic appendectomy. One hundred eighty-five (4.3%) patients were managed conservatively. Major complications occurred in 199 patients (4.6%). The overall mortality rate was 0.28%.

Conclusions

The results of the present study confirm the clinical value of imaging techniques and prognostic scores. Appendectomy remains the most effective treatment of acute appendicitis. Mortality rate is low.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Acute appendicitis (AA) is the most common surgical disease with a lifetime risk of 7–8% [1]. Traditionally, appendectomy has been the treatment of choice for acute appendicitis. Mortality rate after appendectomy is very low and may range from 0.07 to 0.7% rising to 0.5 to 2.4% in patients without and with perforation [2, 3]. Furthermore, overall postoperative complication rates ranged between 10 and 19% for uncomplicated AA and reaching 30% in cases of complicated AA.

Improving the diagnostic pathway is the cornerstone for decreasing the negative appendectomy rate and the risk of wrong diagnosis. Before the wide spread use of CT scans, the diagnosis of acute appendicitis was mainly based on symptoms, signs, and laboratory data.

Several diagnostic scoring systems for acute appendicitis have been described. The most commonly used are the Alvarado score and AIR—Appendicitis Inflammatory Response (Andersson) score [4, 5]. Both of these scoring systems can increase the diagnostic accuracy, thus guiding the decision-making and decreasing the need of potentially harmful and expensive imaging. In view of the potentially higher morbidity associated with open appendectomy, several authors have proposed less invasive management. Although many controversies exist regarding non-operative management of AA, antibiotics play an important role in the treatment of patients with AA as demonstrated by several prospective trials and meta-analyses [6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14]. AA successfully treated with antibiotics remains a potential cause of recurrent appendicitis. Postoperative wound infections and post-appendectomy adhesional bowel obstruction occurring many decades after the index surgery are commonly described sequalae of appendectomies. Therefore, the comparison of surgery and antibiotic therapy still represent a challenging and debated issue.

The effort to distinguish non-complicated from complicated appendicitis is paramount in ensuring appropriate patient management. Utilizing a CT scan to diagnose cases of suspected AA has been demonstrated, it has high sensitivity (0.99) and specificity (0.95) [15,16,17]. However, even a CT scan struggles to differentiate between uncomplicated and complicated appendicitis [18, 19].

In the last decade, the laparoscopic approach has overtaken open surgery for most surgeons worldwide in the treatment of both simple and complicated AA. However, it is not yet unanimously considered the “gold standard” in the management of AA because of its higher operative time, increased intra-abdominal abscess risk, and higher costs compared to open appendectomy. Several meta-analyses of prospective randomized trials were performed in an attempt to define the role of laparoscopic appendectomy [20,21,22,23,24,25]. Literature reports that 2 to 7% of appendicitis tend to present with complex features such as a phlegmon or peri-appendicular abscess [26, 27]. Various published papers suggest treating such patients conservatively, by such methods as ultrasound-guided percutaneous drainage and antibiotic therapy, followed by delayed interval appendectomy [28,29,30,31]. The role of appendectomy after successful drainage and resolution of clinical symptoms is even more controversial than percutaneous drainage. The recommendation for interval appendectomy is based on the risk of recurrence and risk of missing an underlying malignancy [32]. However, the recurrence rate has been reported by several studies to be around 7%, reassuringly low; thus, according to some authors, after successful conservative treatment, an interval appendectomy may not be always necessary [32,33,34,35,36,37].

Recently, a new AA grading system has been proposed by the World Society of Emergency Surgery (WSES). This new grading system is based on clinical presentation, imaging, and surgical findings and aims to provide a standardized classification system based on a uniform patient stratification. The new scoring system intends to aid in determining the optimal post-appendectomy management according to the grade of severity and ultimately contribute to clinical research in appendicitis [38].

Herein we report the results of a prospective observational multicenter worldwide study on AA conducted on behalf of the WSES. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first large-scale observational study on AA performed in institutions from different countries.

Methods

Aim

The primary aim of the POSAW study is to describe the clinical, diagnostic, treatment, and pathological profile of patients with AA in surgical departments of worldwide hospitals.

Study design

This prospective multicenter observational study was performed in 116 worldwide surgical departments from 44 countries over a 6-month period (April 1, 2016—September 30, 2016). All consecutive patients admitted to surgical departments with clinical diagnosis of AA were included in the study. Patient demographics included the following: age, sex, previous episodes of suspected appendicitis, comorbidities (immunosuppression, severe cardiovascular disease, Charlson Comorbidity Index (CCI)) [39], previous antimicrobial therapy, clinical data (axillary temperature, diffuse tenderness, right lower quadrant pain, right lower quadrant tenderness, vomiting) and laboratory findings at admission (white blood count (WBC) and C-reactive protein (CRP)), radiological diagnosis (ultrasound (US) and computer tomography (CT) findings), Alvarado Score, Andersson’s Score [4, 5], type of surgical treatment and adequate source control, WSES Grading System [38], type and duration of antimicrobial therapy, collection of peritoneal swab, microorganisms isolated, admission to intensive care unit (ICU), duration of hospitalization, re-operation, management of postoperative complications at days 7 and 30, Clavien-Dindo Score [40], histopathological findings, and mortality. All patients were monitored until they were discharged or transferred to another ward. The center coordinator of each participating medical institution collected and compiled clinical data in an online case report database. Differences in local surgical practice of each center were respected, and no changes were impinged on local management strategies. Each center followed its own ethical standards and local rules. The study was monitored by a coordinating center, which processed and verified any missing or unclear data submitted to the central database. The study did not attempt to change or modify the clinical practice of the participating physicians: neither informed consent nor formal approval by a local ethics committee was required because of the purely observational nature of the study. The data was completely anonymized, and no patient or hospital information was collected in the website. The study protocol was approved by the board of the WSES, and the study was conducted under its supervision. The board of the WSES grants the proper ethical conduct of the study.

Inclusion criteria

All patients with suspected clinical diagnosis of AA confirmed by imaging and seen by a surgeon were included in the study.

Statistical analysis

Data were analyzed in absolute frequency and percentage, in the case of qualitative variables. Quantitative variables were analyzed as medians and interquartile range (IQR). Univariate analyses were performed to study the association between risk factors and in-hospital mortality using a chi-square test, or a Fisher’s exact test, if the expected value of a cell was < 5. All tests were two-sided, and p values of 0.05 were considered statistically significant. To investigate factors associated with death, we constructed a logistic regression model, including variables with p < 0.05 in the univariate analysis. All statistical analyses were performed using Stata 11 software package (StataCorp, College Station, TX, USA).

Results

Patients and diagnosis

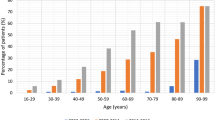

A total of 4282 patients were enrolled in the POSAW study. They included 1928 (45%) women and 2354 (55%) men, with a median age of 29 years (IQR, 21–44). 427 (10%) patients had previous episodes of AA. Seventy-one (1.7%) patients were immunosuppressed, and 154 (3.6%) patients suffered from severe cardiovascular disease. Three thousand six hundred seventy (85.7%) patients had no comorbidities (CCI = 0), 589 (13.8%) patients had a CCI between 1 and 5, and in 23 (0.5%), the CCI was greater than 5. 327 (7.6%) where patients received an antimicrobial therapy in the previous 30 days. Clinical and laboratory findings are reported in Table 1.

Nine hundred and seven (21.2%) patients underwent abdominal CT scan, 1856 (43.3%) patients had an US, 285 (6.7%) patients both CT scan and US, and 1234 (28.8%) patient did not undergo any radiological investigation during hospitalization. Three thousand eight hundred fifty-seven (90.1%) patients had their Alvarado Score recorded, with a median value of 7 (IQR, 6–8). The Alvarado score was ≤ 4 in 460 (11.9%) patients, between 5 and 6 in 1067 (27.7%) patients, between 7 and 8 in 1614 (41.8%) patients, and between 9 and 10 in 716 (18.6%) patients. Three thousand seven hundred fifty-one (87.6%) patients had their Andersson’s Score recorded, with a median value of 6 (IQR, 5–8). In 709 (18.9%) patients, the Andersson’s score was ≤ 4, between 5 and 8 in 2423 (64.6%) patients, and between 9 and 12 in 619 (16.5%) patients. The Alvarado Score was ≥ 5 in 3132 (89.8%) cases of AA confirmed by pathologic exam (RR = 1.11, 1.07–1.15 CI 95%, p < 0.001), while Andersson’s Score was ≥ 5 in 2736 (83.4%) cases of AA confirmed by histopathology (RR = 1.11, 1.07–1.14 CI 95%, p < 0.001).

Management

In 3764 (87.9%) patients, WSES Grading System was recorded. One hundred forty-five (3.8%) patients had grade 0, while 1896 (50.4%) had grade 1, 632 (16.8%) grade 2a, 129 (3.4%) grade 2b, 332 (8.8%) grade 3a, 181 (4.8%) grade 3b, 73 (1.9%) grade 3c, and 376 (10.0%) grade 4.

A total of 4097 (95.7%) patients underwent surgery, of which 1809 (42.2%) underwent open appendectomy and 2215 (51.7%) laparoscopic appendectomy, 19 (0.5%) had open lavage and drainage, 4 (0.1%) had laparoscopic lavage and drainage, 29 (0.7%) had an open ileocaecal resection, 3 (0.1%) had laparoscopic ileocaecal resection, 10 (0.2%) underwent percutaneous drainage, and 8 (0.2%) had other surgical procedures. One hundred eighty-five (4.3%) patients did not undergo any surgical intervention, 48 of these patients had uncomplicated appendicitis.

A total of 3463 (80.9%) patients received antibiotics during the hospitalization, which was monotherapy in the case of 1335 (38.6%) patients (Table 2). The median duration of the antimicrobial therapy was 4 days (IQR, 2–7). Among the 3463 patients who received antibiotics, 583 patients received them as antibiotic prophylaxis.

Intraperitoneal microbiological swab was collected from 803 patients (803/4097, 19.6%) who underwent surgical intervention, resulting in 275 (34.2%) positive cultures. The aerobic and anaerobic bacteria identified in samples of peritoneal fluid are reported in Table 3. Additionally, four Candida albicans isolates were also identified.

Outcome

The median length of hospital stay was 3 days (IQR, 2–5). One hundred and seventy-two patients (4%) had a 1-day hospital stay.

In the early postoperative phase, 184 (184/4097, 2.5%) patients were admitted to the ICU. Fifty-four (54/4097, 1.3%) patients underwent re-laparotomy. A total of 3631 (3631/4097, 88.6%) appendixes were analyzed by histopathology, with the following reports: 144 (4%) were normal appendixes, 236 (6.5%) showed evidence of periappendicitis, 1147 (31.6%) of inflammation, 1176 (32.4%) were suppurative appendixes, 255 (7.0%) showed evidence of perforation, and 673 (18.5%) were gangrenous appendixes.

A total of 3117 (3117/4097, 76.1%) patients were monitored for complications at 7 days after the intervention. Major complications (Clavien-Dindo III–IV) [41] occurred in 199 patients (4.6%). A total of 287 patients (287/3117, 9.2%) developed complications at 7 days. Among these patients with complication, there were 60 with intra-abdominal abscesses (1.9%), 194 surgical site infections (6.2%), 6 paralytic ileus (0.2%), 6 seromas (0.2%), 9 other abdominal complications (0.3%), and 12 other medical complications (0.4%). A total of 2667 (2667/4097, 65.1%) patients were monitored for complication at 30 days after the intervention, and among them, 88 (88/2667, 3.3%) developed a complication. The complications occurred by 30 days were intra-abdominal abscesses (1.3%) in 35 cases, surgical site infections (1.9%) in 51 cases, paralytic ileus (0.1%) in 2 cases, other abdominal complications (0.2%) developed in 6 cases, and other medical complications (0.2%) in 5 cases. The overall mortality rate was 0.28%. The distribution of predictive variables of in-hospital mortality registered at univariate analysis is reported in Table 4. Independent variables associated with mortality according to the multinomial logistic regression are reported in Table 5.

Discussion

AA is one of the most commonly occurring clinical challenges for emergency surgeons, because of its diagnostic work-up. The clinical presentation of AA may vary widely from mild symptoms, like moderate abdominal pain or fever, to most severe scenarios, such as diffuse peritonitis and sepsis [42]. The most frequent clinical symptom is right lower quadrant abdominal pain. If fever with chills is present, systemic involvement should be suspected. However, these symptoms are not specific for AA, since they can be present in other septic conditions, like infectious gastrointestinal disorders or genitourinary tract disorders in young female patients [41]. The median age of 29 years demonstrates the prevalence of this disease in young population. Our data showed that right lower quadrant pain and tenderness were the most frequently reported symptoms (91.2 and 69.6%), followed by vomiting, fever, and diffuse tenderness (42, 24.7, and 11.7%, respectively). Laboratory findings showed a high prevalence of white blood count (WBC) > 10,000 cells/ml (80.2%) and C-reactive protein (CRP) > 10 mg/L in 46.1% of cases. As reported in various studies, WBC and CRP are the most significant laboratory markers to be considered in case of AA. A WBC cut-off > 10,000/ml has a range of sensitivity between 65 and 85% and specificity between 32 and 82%, and CRP values > 10 mg/L have a range of sensitivity between 65 and 85% and specificity between 59 and 73% [43].

Imaging plays a cardinal role in the diagnosis of AA. Reliable imaging in patients with clinical suspicion of appendicitis results in reducing the rate of negative appendectomy by almost 15%. The most commonly used imaging techniques are ultrasonography (US), computed tomography (CT), and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) [43]. In our study, about one third (28.8%) of patients did not undergo any radiological examination, whereas the majority (43.3%) underwent US and only 21.2% had a CT scan. The data demonstrates that often an accurate clinical examination supported by laboratory findings can help the surgeon to manage AA. However, in some cases, a radiological confirmation of the clinical suspicion is paramount, and when US is not sufficient for definitive diagnosis or there is no availability of US-specialized radiologists (i.e., during night-time in some hospitals), a CT scan would be the ideal option, with a sensitivity of 98.5% and a specificity of 98% [44, 45].

Different prognostic scores have been proposed for the clinical evaluation of AA. Alvarado and Appendicitis Inflammatory Responses (AIR; also called Andersson’s score) scores are the most commonly used and validated, being the result of a combination of clinical and biochemical variables with a significant predicting value [4]. Alvarado score has a sensitivity and specificity of 99 and 43% to rule out the diagnosis of AA when < 5 and a sensitivity of 82% and specificity of 81% if < 7. Andersson’s score has a sensitivity of 96% to rule out AA when < 4 and a specificity of 99% to diagnose appendicitis when > 8 [46]. In our study, Alvarado and Andersson’s scores were recorded in 90.1 and 87.6% of cases, respectively. The Alvarado Score was ≥5 in 3132 (89.8%) cases of AA confirmed by pathologic exam (RR = 1.11, 1.07–1.15 CI 95%, p < 0.001), while Andersson’s Score was ≥ 5 in 2736 (83.4%) cases of AA confirmed by pathologic exam (RR = 1.11, 1.07–1.14 CI 95%, p < 0.001).

The WSES grading score [38] was extensively used (87.9%), and about half of the patients were grade 1. In this case, the appendix is inflamed and this is probably the most common situation for an emergency surgeon. WSES grade 1 is also a specific condition where, if the appendix has hyperemia, edema, and fibrin exudates, a significant plasma exudation into the abdominal cavity may occur, with 10% risk of presence of gram-negative bacteria [47]. Therefore, grade 1 appendicitis can sometimes be at risk of developing post-operative peritonitis or abscesses and this risk should be considered, since it is the most common situation recorded in our study. Another important result is the low incidence of WSES grade 0 cases (3.8%), which in the daily practice represents the absence of pathological findings in the appendix. These cases represent the so called “normal-looking appendix” [46]. Such results correlate well with the pathology report of 4% of normal appendixes.

The vast majority of patients in our study underwent surgery (95.7%). More than half the cases were performed laparoscopically (51.7%), 42.2% had open appendectomy, and only 4.3% patients did not receive any surgical treatment. Despite there being several reports in the literature regarding non-operative management of uncomplicated AA [13, 48, 49], this global snapshot from our study demonstrates how operative management still forms the backbone of treatment by surgeons.

Both laparoscopic and open approach are safe and effective techniques for the treatment of suspected AA. Both techniques are associated with good clinical outcomes and few complications [50]. The benefits of laparoscopic approach include reduced incidence of surgical site infections, shorter postoperative stay, less pain, reduced incidence of incisional hernias, and faster postoperative recovery and return to everyday activities, along with better cosmesis [24, 51, 52]. However, the traditional open approach is still widely used, probably due to reduced cost, shorter operative and anesthetic times, the increased risk of intra-abdominal abscess associated with laparoscopic appendectomies and a reduced requirement of higher surgical skill levels [23, 24, 53,54,55].

Recently, WSES recommended the use of broad spectrum antibiotics in case of complicated AA for a minimum duration of 3–5 days of antibiotic treatment [46], and no postoperative antibiotics for uncomplicated appendicitis. In our study, 80.9% of patients received at least one antibiotic during hospitalization for a median duration of 4 days. The most commonly used antiobiotic was metronidazole (58.2%) followed by second- and third-generation cephalosporines (37.0 and 17.2%, respectively). Penicillin with beta-lactam inhibitors were used only in 14.4% cases. The overall number of antibiotics administered (n = 5775) was different from the number of patients receiving antibiotics (n = 3463) since 2128 patients received a combined antimicrobial therapy. This data correlates with the intraoperative findings of positive cultures collected in 275 patients (6.4% of the total population). Escherichia coli (aerobic gram-negative) was found in most of the cultures (57.8%), followed by anaerobic bacteria (Bacteroides spp. 38.2%) and Enterococcus faecalis (aerobic gram-positive) in 15.3%. The overall number of isolated microorganisms (n = 392) was different from the number of positive cultures (n = 275) since from 87 positive cultures, more than one microorganism was isolated. These multiple isolations correlated with the use of multiple antibiotics in about 70% of cases.

The reported incidence of postoperative complications in literature ranges from 3 to 28.7% [56, 57]. The most common complications quoted in the literature are small bowel obstruction, surgical site infection, stump leakage, abdominal abscess, and stump appendicitis [58, 59]. In our study, no stump leakage or stump appendicitis have been reported and although it is reported in the literature as occurring in patients with complicated appendicitis [60], there is no clear evidence of their incidence. Surgical site infection was the most common complication both at 7 and at 30 days after operation (6.2 and 1.9% incidence, respectively) and the reported incidence from the literature ranges between 1.2 and 12%. Small bowel obstruction is reported to have an incidence of around 2%, but in our study its occurrence was as low as 0.2% at 7 days and 0.1% at 30 days, much less than the rates reported in the literature. Abdominal abscesses are the second most frequent complication, with an incidence between 1.6 and 8% [59, 60]. Our study correlated with the incidence of abdominal abscesses reported in the literature with 1.9% at 7 days, but it was much lower at 30 days (1.3%). Complications were not recorded for 100% of the cases included in the study, and this represents a potential bias.

Histopathology showed 32.4% were suppurative appendixes, 31.6% inflammatory, and 18.5% gangrenous appendixes. These represent the majority of pathological diagnosis in case of AA, and they correlate well with preoperative diagnosis and scores registered in our study, but further analyses are necessary to better investigate the correlation between preoperative variables and intra−/postoperative findings. Unfortunately, the present study does not report any data on the incidence of appendiceal tumors, although this finding occurs in about 3% of all appendectomies in the literature [61, 62].

The median hospitalization of 3 days was less than the average length of hospital stay reported in literature [63]. The overall mortality rate following appendectomy in cases of complicated appendectomy can be up to 2.4% [2, 3], and the value of 0.28% is lower than the data reported in literature.

In the bivariate analysis, we have investigated the predictive factors of mortality. Significant variables were age > 80 years, immunosuppression, severe cardiovascular disease, Charlson Comorbidity Score > 5, previous episodes of suspected appendicitis, previous antimicrobial therapy, WSES stages 3c–4, and a pathologic report of perforation. At multivariate analysis, only Charlson Comorbidity Score > 5 (OR 52.45, p < 0.05) and WSES stages 3c (OR 11.77, p < 0.05) and 4 (OR 11.32, p < 0.05) were confirmed as independent variables that were predictors of mortality. Therefore, the presence of serious comorbidities is associated with significantly worse prognosis for such a benign disease, even in absence of complications. Surprisingly, perforation was not an independent risk factor associated to mortality; nonetheless, this should be interpreted with caution, due to the extremely low number of deaths.

Conclusions

The results of the present study gives a snapshot of current worldwide trend in the diagnostic work-up and therapeutic management of AA. Ultrasound is used in about 40% cases and CT in one third. Alvarado, Andersson’s, and WSES grading scores are useful methods to classify the patients, and they predict and correlate with the surgical or pathological diagnosis. More than 90% of patients are treated with surgery, which, in more than 50% cases, is performed using a laparoscopic approach, with a low conversion rate. The hospital stay is usually short, with few complications at 7 and 30 days postoperatively. Even if it is low, the mortality rate seems to correlate with the presence of relevant comorbidities in cases of complicated appendicitis with abscess or peritonitis. Further analysis based on the present data are needed to study in detail the role of preoperative diagnostic work-up, the usefulness of prognostic scores, the potential value of appropriate antibiotic therapy, and the real advantages of a laparoscopic approach.

References

Addiss DG, Shaffer N, Fowler BS, Tauxe RV. The epidemiology of appendicitis and appendectomy in the United States. Am J Epidemiol. 1990;132:910–25.

Blomqvist P, Ljung H, Nyren O, Ekbom A. Appendectomy in Sweden 1989–1993 assessed by the Inpatient Registry. J ClinEpidemiol. 1998;51:859–65.

Margenthaler JA, Longo WE, Virgo KS, Johnson FE, Oprian CA, Henderson WG, et al. Risk factors for adverse outcomes after the surgical treatment of appendicitis in adults. Ann Surg. 2003;238:59–66.

Alvarado A. A practical score for the early diagnosis of acute appendicitis. Ann Emerg Med. 1986;15:557–64.

Andersson M, Andersson RE. The appendicitis inflammatory response score: a tool for the diagnosis of acute appendicitis that outperforms the Alvarado score. World J Surg. 2008;32:1843–9.

Hansson J, Korner U, Khorram-Manesh A, Solberg A, Lundholm K. Randomized clinical trial of antibiotic therapy versus appendicectomy as primary treatment of acute appendicitis in unselected patients. Br J Surg. 2009;96:473–81.

Styrud J, Eriksson S, Nilsson I, Ahlberg G, Haapaniemi S, Neovius G, et al. Appendectomy versus antibiotic treatment in acute appendicitis. A prospective multicenter randomized controlled trial. World J Surg. 2006;30:1033–7.

Vonns C, Barry C, Maitre S, Pautrat K, Leconte M, Costaglioli B, et al. Amoxicillin plus clavulanic acid versus appendicectomy for treatment of acute uncomplicated appendicitis: an open-label, non-inferiority, randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2011;377:1573–9.

Salminen P, Paajanen H, Rautio T, Nordstrom P, Aarnio M, Rantanen T, et al. Antibiotic therapy vs appendectomy for treatment of uncomplicated acute appendicitis: the APPAC Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA. 2015;313:2340–8.

Ansaloni L, Catena F, Coccolini F, Ercolani G, Gazzotti F, Pasqualini E, et al. Surgery versus conservative antibiotic treatment in acute appendicitis: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Dig Surg. 2011;28:210–21.

Liu K, Fogg L. Use of antibiotics alone for treatment of uncomplicated acute appendicitis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Surgery. 2011;150:673–83.

Wilms IM, de Hoog DE, de Visser DC, Janzing HM. Appendectomy versus antibiotic treatment for acute appendicitis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2011;11:CD008359.

Varadhan KK, Neal KR, Lobo DN. Safety and efficacy of antibiotics compared with appendicectomy for treatment of uncomplicated acute appendicitis: meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. BMJ. 2012;344:e2156.

Di Saverio S, Sibilio A, Giorgini E, Biscardi A, Villani S, Coccolini F, et al. The NOTA Study (Non Operative Treatment for Acute Appendicitis): prospective study on the efficacy and safety of antibiotics (amoxicillin and clavulanic acid) for treating patients with right lower quadrant abdominal pain and long-term follow-up of conservatively treated suspected appendicitis. Ann Surg. 2014;260:109–17.

Apisarnthanarak P, Suvannarerg V, Pattaranutaporn P, Charoensak A, Raman SS, Apisarnthanarak A. Alvarado score: can it reduce unnecessary CT scans for evaluation of acute appendicitis? Am J Emerg Med. 2015;33:266–70.

Nelson DW, Causey MW, Porta CR, McVay DP, Carnes AM, Johnson EK, et al. Examining the relevance of the physician's clinical assessment and the reliance on computed tomography in diagnosing acute appendicitis. Am J Surg. 2013;205:452–6.

Duda JB, Lynch ML, Bhatt S, Dogra VS. Computed tomography mimics of acute appendicitis: predictors of appendiceal disease confirmed at pathology. J Clin Imaging Sci. 2012;2:73.

Horton MD, Counter SF, Florence MG, Hart MJ. A prospective trial of computed tomography and ultrasonography for diagnosing appendicitis in the atypical patient. Am J Surg. 2000;179:379–81.

Pinto Leite N, Pereira JM, Cunha R, Pinto P, Sirlin C. CT evaluation of appendicitis and its complications: imaging techniques and key diagnostic findings. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2005;185:406–17.

Bennet J, Boddy A, Rhodes M. Choice of approach for appendicectomy: a meta-analysis of open versus laparoscopic appendicectomy. Surg Laparosc Endosc Percutan Tech. 2007;17:245–55.

Liu Z, Zhang P, Ma Y, Chen H, Zhou Y, Zhang M, et al. Laparoscopy or not: a meta-analysis of the surgical effects of laparoscopic versus open appendicectomy. Surg Laparosc Endosc Percutan Tech. 2010;20:362–70.

Sauerland S, Jaschinski T, Neugebauer EA. Laparoscopic versus open surgery for suspected appendicitis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2010;10:CD001546.

Wei B, Qi CL, Chen TF, Zheng ZH, Huang JL, Hu BG, Wei HB. Laparoscopic versus open appendectomy for acute appendicitis: a metaanalysis. Surg Endosc. 2011;25:1199–208.

Ohtani H, Tamamori Y, Arimoto Y, Nishiguchi Y, Maeda K, Hirakawa K. Meta-analysis of the results of randomized controlled trials that compared laparoscopic and open surgery for acute appendicitis. J Gastrointest Surg. 2012;16:1929–39.

Woodham BL, Cox MR, Eslick GD. Evidence to support the use of laparoscopic over open appendicectomy for obese individuals: a meta-analysis. Surg Endosc. 2012;26:2566–70.

Bradley EL 3rd, Isaacs J. Appendiceal abscess revisited. Arch Surg. 1978;113:130–2.

Bagi P, Dueholm S. Nonoperative management of the ultrasonically evaluated appendiceal mass. Surgery. 1987;101:602–5.

Oliak D, Yamini D, Udani VM, Lewis RJ, Arnell T, Vargas H, et al. Initial nonoperative management for periappendiceal abscess. Dis Colon Rectum. 2001;44:936–41.

Solomkin JS, Mazuski JE, Bradley JS, Rodvold KA, Goldstein EJ, Baron EJ, et al. Diagnosis and management of complicated intra-abdominal infection in adults and children: guidelines by the Surgical Infection Society and the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin Infect Dis. 2010;50:133–64.

Brown CV, Abrishami M, Muller M, Velmahos GC. Appendiceal abscess: immediate operation or percutaneous drainage? Am Surg. 2003;69:829–32.

Sartelli M, Viale P, Koike K, Pea F, Tumietto F, van Goor H, et al. WSES consensus conference: guidelines for first-line management of intra-abdominal infections. World J Emerg Surg. 2011;6:2.

Corfield L. Interval appendicectomy after appendiceal mass or abscess in adults: what is “best practice”? Surg Today. 2007;37:1–4.

Roach JP, Partrick DA, Bruny JL, Allshouse MJ, Karrer FM, Ziegler MM. Complicated appendicitis in children: a clear role for drainage and delayed appendectomy. Am J Surg. 2007;194:769–72. discussion 772-3

You KS, Kim DH, Yun HY, Jang LC, Choi JW, Song YJ, et al. The value of a laparoscopic interval appendectomy for treatment of a periappendiceal abscess: experience of a single medical center. Surg Laparosc Endosc Percutan Tech. 2012;22:127–30.

Keckler SJ, Tsao K, Sharp SW, Ostlie DJ, Holcomb GW III, St Peter SD. Resource utilization and outcomes from percutaneous drainage and interval appendectomy for perforated appendicitis with abscess. J Pediatr Surg. 2008;43:977–80.

Lasson A, Lundagårds J, Lorén I, Nilsson PE. Appendiceal abscesses: primary percutaneous drainage and selective interval appendicectomy. Eur J Surg. 2002;168:264–9.

Kaminski A, Liu IL, Applebaum H, Lee SL, Haigh PI. Routine interval appendectomy is not justified after initial nonoperative treatment of acute appendicitis. Arch Surg. 2005;140:897–901.

Gomes CA, Sartelli M, Di Saverio S, Ansaloni L, Catena F, Coccolini F, et al. Acute appendicitis: proposal of a new comprehensive grading system based on clinical, imaging and laparoscopic findings. World J Emerg Surg. 2015;10:60.

Charlson ME, Pompei P, Ales KL, MacKenzie CR. A new method of classifying prognostic comorbidity in longitudinal studies: development and validation. J Chronic Dis. 1987;40:373–83.

Dindo D, Demartines N, Clavien PA. Classification of surgical complications: a new proposal with evaluation in a cohort of 6336 patients and results of a survey. Ann Surg. 2004;240:205–13.

Ambe PC, Orth V, Gödde D, Zirngibl H. Improving the preoperative diagnostic accuracy of acute appendicitis. Can fecal calprotectin be helpful. PLoS One. 2016;11:e0168769.

Gorter RR, Eker HH, Gorter-Stam MA, Abis GS, Acharya A, Ankersmit M, et al. Diagnosis and management of acute appendicitis. EAES consensus development conference 2015. Surg Endosc. 2016;30:4668–90.

Shogilev DJ, Duus N, Odom SR, Shapiro NI. Diagnosing appendicitis: evidence-based review of the diagnostic approach in 2014. West J Emerg Med. 2014;15:859–71.

Pickhardt PJ, Lawrence EM, Pooler BD, Bruce RJ. Diagnostic performance of multidetector computed tomography for suspected acute appendicitis. Ann Intern Med. 2011;154:789–96. W-291

Krajewski S, Brown J, Phang PT, Raval M, Brown CJ. Impact of computed tomography of the abdomen on clinical outcomes in patients with acute right lower quadrant pain: a meta-analysis. Can J Surg. 2011;54:43–53.

Di Saverio S, Birindelli A, Kelly MD, Catena F, Weber DG, Sartelli M, et al. WSES Jerusalem guidelines for diagnosis and treatment of acute appendicitis. World J Emerg Surg. 2016;11:34.

Gomes CA, Nunes TA, Fonseca Chebli JM, Junior CS, Gomes CC. Laparoscopy grading system of acute appendicitis: new insight for future trials. Surg Laparosc Endosc Percutan Tech. 2012;22:463–6.

Rollins KE, Varadhan KK, Neal KR, Lobo DN. Antibiotics versus appendicectomy for the treatment of uncomplicated acute appendicitis: an updated meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. World J Surg. 2016;40:2305–18.

Podda M, Cillara N, Di Saverio S, Lai A, Feroci F, Luridiana G, et al. Antibiotics-first strategy for uncomplicated acute appendicitis in adults is associated with increased rates of peritonitis at surgery. A systematic review with meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials comparing appendectomy and non-operative management with antibiotics. Surgeon. 2017;15:303–14.

Jaschinski T, Mosch C, Eikermann M, Neugebauer EA. Laparoscopic versus open appendectomy in patients with suspected appendicitis: a systematic review of meta-analyses of randomised controlled trials. BMC Gastroenterol. 2015;15:48.

Massoomi H, Mills S, Dolich MO, Ketana N, Carmichael JC, Nguyen NT, et al. Comparison of outcomes of laparoscopic versus open appendectomy in adults: data from the nationwide inpatient sample (NIS), 2006–2008. J Gastrointest Surg. 2011;15:2226–31.

Xiao Y, Shi G, Zhang J, Cao JG, Liu LJ, Chen TH, et al. Surgical site infection after laparoscopic and open appendectomy: a multicenter large consecutive cohort study. Surg Endosc. 2014;29:1384–93.

Wilson DG, Bond AK, Ladwa N, Sajid MS, Baig MK, Sains P. Intra-abdominal collections following laparoscopic versus open appendicectomy: an experience of 516 consecutive cases at a district general hospital. Surg Endosc. 2013;27:2351–6.

Swank HA, Eshuis EJ, van Berge Henegouwen MI, Bemelman WA. Short- and long-term results of open versus laparoscopic appendectomy. World J Surg. 2011;35:1221–6.

Li X, Zhang J, Sang L, Zhang W, Chu Z, Li X, et al. Laparoscopic versus conventional appendectomy—a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. BMC Gastroenterol. 2010;10:129.

Emil S, Elkady S, Shbat L, Youssef F, Baird R, Laberge JM, et al. Determinants of postoperative abscess occurrence and percutaneous drainage in children with perforated appendicitis. Pediatr Surg Int. 2014;30:1265–71.

Isaksson K, Montgomery A, Moberg AC, Andersson R, Tingstedt B. Long-term follow-up for adhesive small bowel obstruction after open versus laparoscopic surgery for suspected appendicitis. Ann Surg. 2014;259:1173–7.

Gandaglia G, Ghani KR, Sood A, Meyers JR, Sammon JD, Schmid M, et al. Effect of minimally invasive surgery on the risk for surgical site infections: results from the National Surgical Quality Improvement Program (NSQIP) Database. JAMA Surg. 2014;149:1039–44.

Advani V, Ahad S, Gonczy C, Markwell S, Hassan I. Does resident involvement effect surgical times and complication rates during laparoscopic appendectomy for uncomplicated appendicitis? An analysis of 16,849 cases from the ACS-NSQIP. Am J Surg. 2012;203:347–51.

Kanona H, Al Samaraee A, Nice C, Bhattacharya V. Stump appendicitis: a review. Int J Surg. 2012;10:425–8.

Bucher P, Mathe Z, Demirag A, Morel P. Appendix tumors in the era of laparoscopic appendectomy. Surg Endosc. 2004;18:1063–6.

Ma KW, Chia NH, Yeung HW, Cheung MT. If not appendicitis, then what else can it be? A retrospective review of 1492 appendectomies. Hong Kong Med J. 2010;16:12–7.

Ceresoli M, Zucchi A, Allievi N, Harbi A, Pisano M, Montori G, et al. Acute appendicitis: epidemiology, treatment and outcomes—analysis of 16544 consecutive cases. World J Gastrointest Surg. 2016;8:693–9.

Availability of data and materials

WSES online database.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

MS designed the study. MS, FF, and FML wrote the first draft of the manuscript. All the authors reviewed and approved the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The data was completely anonymized, and no patient or hospital information was collected in the database. The study protocol was approved by the board of the WSES, and the study was conducted under its supervision. The board of the WSES grants the proper ethical conduct of the study.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Sartelli, M., Baiocchi, G.L., Di Saverio, S. et al. Prospective Observational Study on acute Appendicitis Worldwide (POSAW). World J Emerg Surg 13, 19 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13017-018-0179-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13017-018-0179-0