Abstract

Background

We are unaware of any studies describing the immediate effects of scoliosis-specific exercises on the Cobb angle measured by radiograph. This study aimed to describe the differences between radiographs obtained with and without corrective exercises after initial training and after one year.

Methods

A female with adolescent idiopathic scoliosis was first seen at age 13 years, 0 months with a Risser 0. She had a 43o left lumbar, 15o right thoracic curve. She was seen again after 6, 18 and 30 months and performed exercises from 18 to 30 months. She performed Barcelona Scoliosis Physical Therapy School (BSPTS) exercises for a four-curve type (lumbar dominant with pelvis deviation to the lumbar concave side). At 18 and 30 months, x-rays were obtained with and without performing corrective exercises.

Results

At 6 months, her lumbar and thoracic curves measured 41o and 28o, respectively. At 18 months, her lumbar and thoracic curves measured 47 o and 30o, respectively. Also at 18 months, immediately after her x-ray in the relaxed standing position, she performed her corrective exercises in standing with arms lowered for a second x-ray. Her lumbar and thoracic curves remained similar and measured 43o and 32o, respectively. At 30 months, she performed unsolicited corrective exercises during the x-ray. Her lumbar and thoracic curves measured 26o and 41o, respectively. Another x-ray in the relaxed position revealed lumbar and thoracic curves measuring 39o and 35o, respectively. The immediate effect of corrective exercises after a year of training was a 33 % improvement at the lumbar spine compared to only a 9 % improvement the previous year.

Conclusion

After initial training, corrective exercises during a standing x-ray did not significantly improve the Cobb angle for the major lumbar curve compared to the relaxed standing x-ray. However, a year after performing exercises, unsolicited corrective exercises resulted in a significantly improved Cobb angle compared to relaxed standing for the curve primarily targeted by the exercise program. Improved exercise ability and spinal flexibility may have contributed to the improved Cobb angle.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Auto-corrective exercises are integral to scoliosis-specific exercises [1–4]. The Cobb angle measured by radiograph is the most commonly used outcome measure to assess curve magnitude [5]. However, it is unclear whether and how corrective exercises affect the Cobb angle. A number of promising studies showed that Schroth corrective exercises for patients with scoliosis can slow curve progression or help patients achieve some curve correction [2, 3, 6–9]. We are also unaware of any studies describing the immediate effects of scoliosis-specific exercises on the Cobb angle. In an article on the Scientific Exercise Approach to Scoliosis (SEAS) method, Romano et al. [10] demonstrated x-ray images of one patient in a relaxed position and during corrective exercises [10]. However, no details were provided including the time frame of the x-rays and measurements of the exact Cobb angles. The aim of this study is to describe the differences between radiographs obtained with and without corrective exercises after initial training and after one year.

Methods

Since this is a de-identified case study, IRB approval was not required.

Case presentation

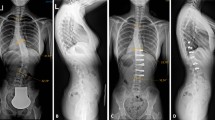

A female with adolescent idiopathic scoliosis was first seen at age 13, 0 months with a Risser 0, 2 months post-menarche. She had a 43o left lumbar, 15o right thoracic curve (Fig. 1). She had worn a Providence night-time brace for three months. At 6 months, her lumbar and thoracic curves measured 41o and 28o, respectively. Her Risser was 1−2 and she had grown 3 cm (Fig. 2). She was seen again after 6, 18 and 30 months. At the 18 month visit, she was instructed in Barcelona Scoliosis Physical Therapy School (BSPTS) exercises for a four-curve type (lumbar dominant with pelvis deviation to the lumbar concave side) [11]. See Fig. 3 for a clinical picture of her relaxed standing posture. She attended 8 visits for 2 h each over one week of intensive instruction by a BSPTS-certified physical therapist with 7 months of experience. After discharge from physical therapy, she was asked to alternate performing 5 of 8 home exercises (semi-hanging, prone-on-knees, prone-on-stool, sidelying, side-sitting, rotational-sitting, sitting, standing) for 30 min per day, 5 times a week. No direct care was provided during this interval, since the patient did not have access to a trained physical therapist. She performed exercises from 18 to 30 months. At 18 and 30 months, x-rays were obtained with and without performing corrective exercises without the physical therapist present.

Results

At 18 months, her lumbar and thoracic curves measured 47o and 30o, respectively. Her Risser was 4. The brace was discontinued. Also at 18 months, immediately after her x-ray in the relaxed standing position, she performed her corrective exercises in standing with arms lowered for a second x-ray (Fig. 4). She performed the pelvis corrections for her curve type, auto-elongation, opening of her concavities, depressing her convexities, and shoulder counter-traction. Her lumbar and thoracic curves changed by less than 5o and measured 43o and 32o, respectively. At 30 months, one year after exercise instruction, her lumbar and thoracic curves measured 26o and 41o, respectively. She later explained her improved x-ray, stating she had used corrective exercises during the x-ray (without being asked). Another x-ray was obtained in relaxed position during the same visit. Her lumbar and thoracic curves measured 39o and 35o, respectively (Fig. 5). She was Risser 4 and had grown 1 cm the past year. The patient and parents reported home exercise compliance at 1–3 times a week the past year. The immediate effect of corrective exercises after a year of training was a 33 % improvement (13o) at the lumbar spine compared to only a 9 % (4o) improvement the previous year. The Cobb angle at the lumbar curve improved in the relaxed standing position by 8 o in the standing relaxed position compared to the 18 month visit. However, the Cobb angle at the thoracic curve worsened from 18 to 30 months (5° in the standing relaxed position and 9° with unsolicited correction).

Conclusion

The patient’s thoracic curve worsened slightly from her 18 month visit to her 30 month visit although she approached skeletal maturity (Risser 4, 1 cm growth). She was treated as a 4C curve type (dominant lumbar curve with a nondominant thoracic curve), but the focus of the corrections were at the main curve (lumbar spine). It is difficult to say whether the corrective exercises had a negative effect on the nondominant thoracic curve, since clinically the patient appeared more balanced. Auto-corrrective exercises should improve alignment throughout the spine in three dimensions [4]. However, it can be challenging to improve each aspect of spinal deformity with multiple and even opposing body blocks. Perhaps a bigger focus should have been placed on the thoracic curve. The thoracic spine is stiffer than the lumbar spine due to the ribs attaching to the lumbar spine. Future studies should investigate whether other patients have experienced curve progression at the nondominant curves despite approaching skeletal maturity. Other Schroth studies only reported curve magnitude at the main curves [6, 7, 9] or did not report data specifically about the secondary curves [8].

Since patients are able to improve their Cobb angle for radiographs, we emphasize that patients should stand in their relaxed posture for x-rays at all visits to follow proper standardized radiographic procedures. However, it is possible that patients that utilize scoliosis-specific exercises perform their corrective exercises during radiographs which may result in overestimated exercise effects. However, one could also argue that radiographs displaying exercise corrections despite requesting that patients stand in a relaxed natural position can capture patients’ ability to hold a corrected position throughout their daily life. Future exercise studies should clarify instructions given to patients during radiographic acquisition. Also, with an increasing availability of EOS imaging which includes significantly lower radiation effects, [12] facilities could consider imaging patients in both their relaxed and corrected postures. EOS imaging may monitor the ability of patients to perform their corrective exercises, to understand the relative effect of various corrective instructions, and to determine the effect of the three-dimensional nature of the exercises (planes of maximum deformity or angles of rotation).

After initial training, corrective exercises during a standing x-ray did not significantly improve the Cobb angle for the major lumbar curve compared to the relaxed standing x-ray. However, a year after performing exercises, unsolicited corrective exercises resulted in a significantly improved Cobb angle compared to relaxed standing for the curve primarily targeted by the exercise program. Improved exercise ability and spinal flexibility may have contributed to the improved Cobb angle. Wearable technology is needed to better understand how much time patients are spending in their corrected versus relaxed postures.

References

Negrini S, Aulisa AG, Aulisa L, Circo AB, de Mauroy JC, Durmala J, Grivas TB, Knott P, Kotwicki T, Maruyama T, Minozzi S, O'Brien JP, Papadopoulos D, Rigo M, Rivard CH, Romano M, Wynne JH, Villagrasa M, Weiss HR, Zaina F. 2011 SOSORT guidelines: Orthopaedic and rehabilitation treatment of idiopathic scoliosis during growth. Scoliosis. 2012;7(1):3.

Romano M, Minozzi S, Bettany-Saltikov J, Zaina F, Chockalingam N, Kotwicki T, Maier-Hennes A, Negrini S. Exercises for adolescent idiopathic scoliosis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;8:CD007837.

Monticone M, Ambrosini E, Cazzaniga D, Rocca B, Ferrante S. Active self-correction and task-oriented exercises reduce spinal deformity and improve quality of life in subjects with mild adolescent idiopathic scoliosis. Results of a randomised controlled trial. Eur Spine J. 2014;23(6):1204–14.

Fusco C, Zaina F, Atanasio S, Romano M, Negrini A, Negrini S. Physical exercises in the treatment of adolescent idiopathic scoliosis: An updated systematic review. Physiother Theor Pract. 2011;27(1):80–114.

Langensiepen S, Semler O, Sobottke R, Fricke O, Franklin J, Schönau E, Eysel P. Measuring procedures to determine the Cobb angle in idiopathic scoliosis: a systematic review. Eur Spine J. 2013;22(11):2360–71.

Kuru T, Yeldan İ, Dereli EE, Özdinçler AR, Dikici F, Çolak İ. The efficacy of three-dimensional Schroth exercises in adolescent idiopathic scoliosis: A randomised controlled clinical trial. Clin Rehabil. 2016;30(2):181–90.

Noh DK, You JS, Koh JH, Kim H, Kim D, Ko SM, Shin JY. Effects of novel corrective spinal technique on adolescent idiopathic scoliosis as assessed by radiographic imaging. J Back Musculoskelet Rehabil. 2014;27(3):331–8.

Schreiber S. Schroth exercises for adolescent idiopathic scoliosis – reliability, a randomized controlled trial and clinical significance. PhD dissertation. University of Alberta, Faculty of Rehabilitation Medicine; 2015

Otman S, Kose N, Yakut Y. The efficacy of Schroth’s 3-dimensional exercise therapy in the treatment of adolescent idiopathic scoliosis in Turkey results. Neurosci. 2005;10(4):277–83.

Romano M, Negrini A, Parzini S, Tavernaro M, Zaina F, Donzelli S, Negrini S. SEAS (Scientific Exercises Approach to Scoliosis): a modern and effective evidence based approach to physiotherapic specific scoliosis exercises. Scoliosis. 2015;10(3):3–19.

Rigo MD, Villagrasa M, Gallo D. A specific scoliosis classification correlating with brace treatment: description and reliability. Scoliosis. 2010;5(1):1.

Deschênes S, Charron G, Beaudoin G, Labelle H, Dubois J, Miron MC, Parent S. Diagnostic imaging of spinal deformities: reducing patients radiation dose with a new slot-scanning X-ray imager. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2010;35(9):989–94.

Declarations

This article has been published as part of Scoliosis and Spinal Disorders Volume 11 Supplement 2, 2016. Research into Conservative Management of Spinal Deformities: Short Articles from the SOSORT 2015 Meeting. The full contents of the supplement are available online http://scoliosisjournal.biomedcentral.com/articles/supplements/volume-11-supplement-2.

Availability of data and materials

All the data pertinent to this case is in the manuscript.

Authors’ contributions

KZ was the treating physical therapist. DS was the patient’s orthopaedic surgeon. KZ, DS, and EP helped draft the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Consent for publication

Consent for publication was received by the parent; assent was received by the patient.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study received a letter of exemption from Texas Scottish Rite Hospital’s Institutional Review Board.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Zapata, K., Parent, E.C. & Sucato, D. Immediate effects of scoliosis-specific corrective exercises on the Cobb angle after one week and after one year of practice. Scoliosis 11 (Suppl 2), 36 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13013-016-0101-z

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13013-016-0101-z