Abstract

Background

Timely initiation of breastfeeding is putting the newborn to the breast within 1 h of birth. Its practice can prevent neonatal and under-5 mortality. This study aims to assess the prevalence and factors associated with timely initiation of breastfeeding among mothers in Ghana.

Methods

We used data from the 2017–2018 Ghana multiple indicator cluster survey and our analysis was restricted to 15,305 mothers who had a live birth within 2 years. Multivariable logistic regression was used to estimate the factors associated with timely initiation of breastfeeding whilst adjusting for potential confounders, and accounted for clustering, stratification, and sample weights.

Results

The prevalence of timely initiation of breastfeeding was 51.3% (95% CI 48.1, 54.6%). Mothers who received antenatal care were twice as likely to timely initiate breastfeeding compared to mothers who did not receive antenatal care (Adjusted prevalence odds ratios [aPOR] 2.01, 95% CI 1.03, 3.95). Mothers who were assisted by a skilled attendant at birth had 90% higher odds of timely initiation of breastfeeding compared to mothers who were not assisted by a skilled attendant (aPOR 1.90, 95% CI 1.41, 2.55). Mothers who delivered by caesarean section had 76% lower odds of timely initiation of breastfeeding compared to mothers who had a vaginal delivery (aPOR 0.24, 95, 95% CI 0.16, 0.36). Mothers who had planned their pregnancy had 45% higher odds of timely initiation of breastfeeding compared to mothers who had an unplanned pregnancy (aPOR 1.45, 95% CI 1.09, 1.92). There were also 84% and 55% higher odds of timely initiation of breastfeeding among mothers who perceived their baby was large (aPOR 1.84, 95% CI 1.32, 2.58), and of average size (aPOR 1.55, 95% CI 1.11, 2.17) at birth respectively, compared to mothers who perceived their baby was small.

Conclusions

Interventions to increase timely initiation of breastfeeding should provide breastfeeding support to mothers who have had a caesarean section or small sized babies, prevent unplanned pregnancies, and promote antenatal care attendance among pregnant women.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Appropriate child feeding practice involves timely initiation of breastfeeding, 6 months of exclusive breastfeeding and complementary feeding from 6 to 24 months of the child’s age, even though breastfeeding may continue to more than 2 years of age [1]. Timely initiation of breastfeeding is putting the newborn to the breast within 1 h of birth [2]. Colostrum is the first breast milk and its ingestion by the newborn within the first hour of life confers passive and active immunity to the neonate against a wide variety of pathogens [3]. The rich protective factors in colostrum can reduce neonatal mortality when given to the newborn within the first hour of birth [4]. The risk of neonatal mortality is high when breastfeeding is not initiated within the first hour [5]. Colostrum also helps develop a healthy gut microbiome which can have long term health benefits [6]. Timely initiation of breastfeeding also stimulates the release of oxytocin and enables contraction of the uterus and decreases postpartum haemorrhage [7]. It also facilitates mother-infant bonding and is positively associated with exclusive breastfeeding practice [8].

In spite of the benefits of timely initiation of breastfeeding, globally only 39% of mothers initiated breastfeeding within the first hour of life, and this varies across regions [9]. Studies have found that factors such as household wealth, maternal education and place of residence are positively associated with the prevalence of timely initiation of breastfeeding [4, 8, 10,11,12,13], but these findings have been inconsistent. Whilst John et al. found that wealthier mothers were more likely to initiate breastfeeding within the first hour of birth than their poor counterparts, Khanal and his colleagues observed that mothers from poor household were more likely to timely initiate breastfeeding [11, 13]. Studies in Zimbabwe and Bangladesh also found that mothers from rural settings timely initiated breastfeeding compared to their peers from urban households [10, 12], but these were contrary to findings in Ethiopia and Nigeria [14, 15].

In Ghana, the policy on breastfeeding advocates for mothers to timely initiate breastfeeding, practice 6 months of exclusive breastfeeding followed by introduction of complementary foods with continued breastfeeding till the child is 2 years old and beyond [16]. Edmond et al. in Ghana observed that 22% of neonatal deaths can be saved if mothers initiate breastfeeding within the first 1 h of birth [4]. Whilst timely initiation of breastfeeding plays an important role in reducing neonatal mortality in Ghana, studies on factors associated with timely initiation of breastfeeding in Ghana are limited [17]. There is also considerable variation in the prevalence of timely initiation of breastfeeding in Ghana [17,18,19,20], and most of these studies were not nationally representative [18,19,20]. Therefore, our primary aim was to assess the prevalence and predictors of timely initiation of breastfeeding among mothers using the most recent multiple indicator cluster survey (MICS). The findings of this study will be relevant in designing appropriate interventions to improve timely initiation of breastfeeding in Ghana.

Methods

Study design, study population and data collection

We used data from the MICS conducted in Ghana from 2017 to 2018. The MICS is a representative household survey which provides national data on women and children [21]. The study population was made up of women of reproductive age (15–49 years) with a live birth within 2 years. The MICS uses a two-stage sampling procedure which involves selection of census enumeration areas from each sampling strata using a probability proportionate to the number of households in an enumeration area. The second stage of sampling employs a systematic random sampling to select households from each enumeration area to form survey clusters. Detailed description of the MICS sampling design and procedures are published elsewhere [22, 23].

Primary outcome

Our primary outcome of interest was timely initiation of breastfeeding. Timely initiation of breastfeeding was defined as a mother who puts her baby to the breast within 1 h of birth [14].

Predictors

The predictors in our study were antenatal care attendance, delivery assisted by a skilled attendant, mode of delivery, planned pregnancy and perceived delivery size of baby. We compared mothers who had received at least one antenatal care to mothers who did not receive antenatal care. We also compared mothers who perceived the size of their baby at birth was larger than average, and mothers who perceived their baby was of average size to mothers who perceived their babies were smaller than the average size. Other predictors were categorized as: delivery assisted by a skilled attendant (yes, no); mode of delivery (cesarean section, vaginal delivery); and planned pregnancy (yes, no). A skilled attendant was any health professional such as a doctor, midwife or nurse who assisted the mother at delivery.

Covariates

Our covariates of interest were: mother’s age, marital status, educational level of mothers, household wealth and place of residence. Mother’s ages were categorized as 15–24, 25–34 and 35–49 years. Marital status was categorized as married/cohabitation and never married. The educational level of mothers was categorized as no formal education, primary, secondary and college or higher education. We used household wealth quintiles to construct upper two, middle and lower two wealth quintiles which were used to denote high income, middle income, and poor income households respectively. Place of residence was either rural or urban.

Data analysis

We conducted descriptive statistics and logistic regression analysis using SAS version 9.3 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC). Descriptive statistics were used to assess the prevalence and characteristics of study population. Complex survey univariate logistic and multivariable logistic regression models were used to assess the relationship between predictor variables and our primary outcome of interest. In the multivariable logistic regression analysis, we adjusted for potential confounders (i.e. covariates) as a priori, as we believe there is a biological plausibility that they might be associated with both predictor variables and primary outcome. In all our analysis and because of the complex sampling design, we accounted for clustering, stratification, and applied sampling weights to ensure representativeness of our results. A P - value of less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Characteristics of the study population and prevalence of timely initiation of breastfeeding

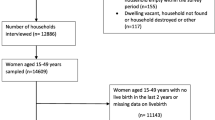

The study population was made up of 15,305 mothers with a live birth in the past 2 years (Fig. 1). The number of hospitals in our study that served as a place of delivery for mothers were made up of 6317 Government hospitals and 839 private hospitals. The mean age of mothers was 28.6 years (results not shown). Our study included 6920 (48.4%) mothers who were aged 25–34 years, 12,831 (84.5%) were married/cohabitation. Majority of the mothers had a secondary level of education, 7133 (49.2%). Most of the mothers were from poor income households, 8063 (43.6%), and more than half of them were living in rural settings, 9910 (60.7%) (Table 1).

The overall prevalence of timely initiation of breastfeeding was 51.3% (95% CI 48.1, 54.6%) with 1.34% (95% CI 0.71, 1.99%) of mothers not breastfeeding at all. The prevalence of timely initiation of breastfeeding was similar among mothers that were never married, 49.2% (95% CI 42.4, 55.9%) and mothers that were married/cohabitation, 51.8% (95% CI 48.2, 55.3%). This was also similar among mothers with different levels of education: no formal education (50.1, 95% CI 44.3, 55.9%); primary (49.8, 95%: 43, 56.5%); secondary (52.9, 95% CI 48.8, 57%); and college or higher education (49.2, 95% CI 36, 62.3%). The prevalence of timely initiation of breastfeeding was also comparatively similar among mothers living in rural settings, 51.9% (95% CI 48.1, 55.7%) to those in urban settings, 50.5% (44.7, 56.3%). We did however observe that the prevalence of timely initiation of breastfeeding was higher among mothers that had a planned pregnancy (55.6, 95% CI 51.5, 59.6%), received antenatal care (52, 95%, CI 48.6, 55.3%), had a vaginal delivery (54.6%, 95% CI 51.2, 58%), and was assisted by a skilled attendant (54.2, 95% CI 50.3, 58.1%), compared to mothers who did not plan their pregnancy (47.4, 95% CI 42.7, 52.2%), received no antenatal care (28.2, 95% CI 15, 41.4%), had a cesarean section (26.6, 95% CI 19.5, 33.7%), and were not assisted by a skilled attendant (42, 95% CI 36.4, 47.6%), respectively (Table 1).

Predictors of timely initiation of breastfeeding

The multivariable logistic regression results showed that mothers who received antenatal care were twice more likely to timely initiate breastfeeding compared to mothers who did not receive antenatal care (Adjusted prevalence odds ratios [aPOR] 2.01, 95% CI 1.03, 3.95). Mothers who were assisted by skilled attendant during delivery had 90% higher odds of timely initiation of breastfeeding as compared to mothers who were not assisted by a skilled attendant at birth (aPOR 1.90, 95% CI 1.41, 2.55). Mothers who had a caesarean section had 76% lower odds of timely initiation of breastfeeding compared to mothers who had a vaginal delivery (aPOR 0.24, 95, 95% CI 0.16, 0.36). Mothers whose pregnancies were planned had 45% higher odds of timely initiation of breastfeeding compared to their peers who had unplanned pregnancies (aPOR 1.45, 95% CI 1.09, 1.92). Mothers who perceived that their babies were larger than average size (aPOR 1.84, 95% CI 1.32, 2.58), and of average size (aPOR 1.55, 95% CI 1.11, 2.17), at birth had 84% and 55% higher odds of timely initiation of breastfeeding respectively, compared to mothers who perceived their babies were smaller than average size at birth. However, the age of a mother, educational level, household wealth, marital status and place of residence were not associated with timely initiation of breastfeeding (Table 2).

Discussion

Our study found that overall, one out of two mothers initiated breastfeeding within the first hour of birth. Our results showed that planned pregnancy, receiving antenatal care, delivery assisted by a skilled attendant and perceived size (average\large) were positively associated with timely initiation of breastfeeding, whilst caesarean section was negatively associated with timely initiation of breastfeeding. However, age, marital status, education, household wealth, and place of residence were not associated with timely initiation of breastfeeding.

The overall prevalence of timely initiation of breastfeeding in our study is higher than the reported overall prevalence of timely initiation of breastfeeding in the West African and Central African sub regions [24]. Timely initiation of breastfeeding in Ghana has increased from 45.9% in 2011 to 51.3% in 2018 [25]. Despite Ghana’s modest improvement in the prevalence of timely initiation of breastfeeding over the 7 year period, the prevalence is still markedly lower than its target of ensuring that 85% of all newborns are breastfed within the first 1 h of birth [26]. It has been predicted by Duodu et al. that Ghana may meet its target of timely initiation of breastfeeding by 2044 [17]. The prevalence of timely initiation of breastfeeding in Ghana is also substantially lower than that reported in countries such as Ethiopia (74.3%), Malawi (76.9%), Sudan (69%), Rwanda (81.5%), and Mozambique (77.7%) [11, 24, 27, 28]. The differences in prevalence of timely initiation of breastfeeding across countries might be attributed to differences in socio-cultural context, economy and health inequalities [11].

We found that mothers whose pregnancies were planned were more likely to initiate breastfeeding within the first hour of birth compared to mothers who had an unplanned pregnancy. This is consistent with a previous study in Turkey [29], and may reflect the poor breastfeeding behavior among mothers who had an unplanned pregnancy [30]. The lower prevalence of timely initiation of breastfeeding among mothers who had an unplanned pregnancy compared to mothers whose pregnancies were planned in our study may be attributed to delayed prenatal care, premature birth and negative physical and mental health effects associated with mothers who do not plan their pregnancies [31,32,33]. These adverse maternal and child health outcomes might account for the low prevalence of timely initiation of breastfeeding among mothers whose pregnancies were unplanned.

Our findings on the negative association between mothers who had a caesarean section and timely initiation of breastfeeding is corroborated with many previous studies in low-and middle-income countries [8, 10,11,12, 17]. There are several possible reasons that might account for the low prevalence of timely initiation of breastfeeding among mothers that had a caesarean section compared to mothers who had vaginal delivery. Mothers who had a caesarean section might need some time to recover from anaesthesia and may also not be comfortable adapting to breastfeeding positions [8, 34]. Newborns delivered by a caesarean section might suffer respiratory distress and this can lead to separation from their mothers [8].

Our finding on the positive association between assisted delivery by a skill attendant and timely initiation of breastfeeding was not surprising as we expect health professionals to do the right thing by supporting mothers to initiate breastfeeding within an hour compared to traditional birth attendants.

Our analysis showed that antenatal care attendance of at least one visit was associated with timely initiation of breastfeeding. This finding was consistent with results from Mekonen et al. in Ethiopia [14]. This finding in our study might be because antenatal care offers a unique opportunity for healthcare professional to educate women not only about their pregnancy, but on childbirth and neonatal care.

We did also observe in our results that mothers who perceived their babies were of average size or larger than average size at birth were more likely to timely initiate breastfeeding than mothers who perceived their babies were below average size. This finding is in agreement with previous studies [15, 35]. Average or large size babies are often healthy with strong breastfeeding reflexes, and this is associated with timely initiation of breastfeeding [36]. On the contrary small sized babies are often low birthweight, premature and have weak sucking reflexes, poor coordination coupled with difficulty in swallowing [15, 36]. This finding in our study suggests that mothers with small sized infant will require more breastfeeding support to initiate breastfeeding within the first hour of birth. In our results, we also found that marital status, age, education, household wealth, and place of residence were not associated with timely initiation of breastfeeding. Our findings on place of residence, household wealth and education level of the mothers were consistent with results from Bangladesh [37], but were in contrast to many previous studies [8, 11, 27].

The strength of our study is its national representative sample which allows for our findings to be generalized to Ghanaian mothers. However, our study had some limitations. The cross-sectional sample does not allow for our findings to infer causality. Some of our predictor variables were not objectively measured and were subject to measurement error. For example, perceived size of a baby at delivery is not an accurate measure of the weight of a baby. Our predictor variables were also self-reported, and thus are subject to recall bias. We expect recall bias to be similar between mothers who timely initiated breastfeeding, and those who did not. We also expect recall bias on our primary outcome to be similar between exposed and non-exposed predictor variables. We also could not control for potential confounders such as medications that could potentially prevent mothers from timely initiating breastfeeding.

Conclusions

This study found that receiving antenatal care, a planned pregnancy, assisted delivery by a skilled attendant and perceived average or large size of a baby at birth were positively associated with timely initiation of breastfeeding. However, caesarean section was negatively associated with timely initiation of breastfeeding. Interventions to increase timely initiation of breastfeeding in Ghana should focus on providing breastfeeding support to mothers who have had a caesarean section and mothers who have had small sized babies. Interventions should also educate women to attend antenatal care and on the prevention of unplanned pregnancies.

Availability of data and materials

MICS data is publicly available at: https://mics.unicef.org/surveys.

Change history

04 February 2021

A Correction to this paper has been published: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13006-021-00362-8

Abbreviations

- aPOR:

-

Adjusted prevalence odds ratios

- MICS:

-

Multiple indicator cluster survey

References

WHO, UNICEF. Global strategy for infant and young child feeding; 2003. http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/42590/9241562218.pdf. Accessed 22 May 2020.

Alebel A, Dejenu G, Mullu G, Abebe N, Gualu T, Eshetie S. Timely initiation of breastfeeding and its association with birth place in Ethiopia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int Breastfeed J. 2017;12:44.

Bardanzellu F, Fanos V, Reali A. “Omics” in human colostrum and mature milk: looking to old data with new eyes. Nutrients. 2017;9(8):843.

Edmond KM, Zandoh C, Quigley MA, Amenga-Etego S, Owusu-Agyei S, Kirkwood BR. Delayed breastfeeding initiation increases risk of neonatal mortality. Pediatrics. 2006;117(3):e380–6.

Victora CG, Bahl R, Barros AJ, França GV, Horton S, Krasevec J, et al. Breastfeeding in the 21st century: epidemiology, mechanisms, and lifelong effect. Lancet. 2016;387(10017):475–90.

McGee M, Earley B. Review: passive immunity in beef-suckler calves. Animal. 2019;13(4):810–25.

Palmeira P, Carneiro-Sampaio M. Immunology of breast milk. Rev Assoc Med Bras (1992). 2016;62(6):584–93.

Liben ML, Yesuf EM. Determinants of early initiation of breastfeeding in Amibara district, Northeastern Ethiopia: a community based cross-sectional study. Int Breastfeed J. 2016;11:7.

Oakley L, Benova L, Macleod D, Lynch CA, Campbell OMR. Early breastfeeding practices: descriptive analysis of recent demographic and health surveys. Matern Child Nutr. 2018;14(2):e12535.

Islam MA, Mamun A, Hossain MM, Bharati P, Saw A, Lestrel PE, et al. Prevalence and factors associated with early initiation of breastfeeding among Bangladeshi mothers: a nationwide cross-sectional study. PLoS One. 2019;14(4):e0215733.

John JR, Mistry SK, Kebede G, Manohar N, Arora A. Determinants of early initiation of breastfeeding in Ethiopia: a population-based study using the 2016 demographic and health survey data. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2019;19:69.

Mukora-Mutseyekwa F, Gunguwo H, Mandigo RG, Mundagowa P. Predictors of early initiation of breastfeeding among Zimbabwean women: secondary analysis of ZDHS 2015. Matern Health Neonatol Perinatol. 2019;5:2.

Khanal V, Scott JA, Lee AH, Karkee R, Binns CW. Factors associated with early initiation of breastfeeding in Western Nepal. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2015;12(8):9562–74.

Mekonen L, Seifu W, Shiferaw Z. Timely initiation of breastfeeding and associated factors among mothers of infants under 12 months in South Gondar zone, Amhara regional state, Ethiopia; 2013. Int Breastfeed J. 2018;13:17.

Berde AS, Yalcin SS. Determinants of early initiation of breastfeeding in Nigeria: a population-based study using the 2013 demograhic and health survey data. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2016;16:32.

Ministry of Health. Under Five’s Child Health Policy: 2007-2015; 2007. https://extranet.who.int/nutrition/gina/sites/default/files/GHA%202007%20Under%20Five%27s%20Child%20Health%20Policy%202007%20-%202015.pdf. Accessed 22 May 2020.

Duodu PA, Duah HO, Dzomeku VM, Boamah Mensah AB, Aboagye Mensah J, Darkwah E, et al. Consistency of the determinants of early initiation of breastfeeding in Ghana: insights from four demographic and health survey datasets; 2020. https://academic.oup.com/inthealth/advance-article/doi/10.1093/inthealth/ihaa017/5821035. Accessed 30 Sep 2020.

Asare BY, Preko JV, Baafi D, Dwumfour-Asare B. Breastfeeding practices and determinants of exclusive breastfeeding in a cross-sectional study at a child welfare clinic in Tema Manhean, Ghana. Int Breastfeed J. 2018;13:12.

Nukpezah RN, Nuvor SV, Ninnoni J. Knowledge and practice of exclusive breastfeeding among mothers in the tamale metropolis of Ghana. Reprod Health. 2018;15:140.

Dun-Dery EJ, Laar AK. Exclusive breastfeeding among city-dwelling professional working mothers in Ghana. Int Breastfeed J. 2016;11:23.

Khan S, Hancioglu A. Multiple Indicator cluster surveys: delivering robust data on children and women across the globe. Stud Fam Plan. 2019;50(3):279–86.

UNICEF. Multiple Indicator Cluster Survey (MICS); 2020. https://mics.unicef.org/. Accessed 22 May 2020.

National Bureau of Statistics and UNICEF. Multiple indicator cluster survey, survey findings report. Abuja: National Bureau of Statistics and United Nations Children’s Fund; 2017.

Issaka AI, Agho KE, Renzaho AM. Prevalence of key breastfeeding indicators in 29 sub-Saharan African countries: a meta-analysis of demographic and health surveys (2010-2015). BMJ Open. 2017;7(10):e014145.

Ghana Statistical Service. Ghana Multiple Indicator Cluster Survey with an Enhanced Malaria Module and Biomarker, 2011, final report. Accra: Ghana Statistical Service; 2011.

Ghana Health Service. Ghana Health Service 2016 annual report Accra , Ghana; 2017.

Nkoka O, Ntenda PAM, Kanje V, Milanzi EB, Arora A. Determinants of timely initiation of breast milk and exclusive breastfeeding in Malawi: a population-based cross-sectional study. Int Breastfeed J. 2019;14:37.

Abdel-Rahman ME, El-Heneidy A, Benova L, Oakley L. Early feeding practices and associated factors in Sudan: a cross-sectional analysis from multiple Indicator cluster survey. Int Breastfeed J. 2020;15:41.

Yılmaz E, Doğa Öcal F, Vural Yılmaz Z, Ceyhan M, Kara OF, Küçüközkan T. Early initiation and exclusive breastfeeding: factors influencing the attitudes of mothers who gave birth in a baby-friendly hospital. Turk J Obstet Gynecol. 2017;14(1):1–9.

Kimani-Murage EW, Wekesah F, Wanjohi M, Kyobutungi C, Ezeh AC, Musoke RN, et al. Factors affecting actualisation of the WHO breastfeeding recommendations in urban poor settings in Kenya. Matern Child Nutr. 2015;11(3):314–32.

Gipson JD, Koenig MA, Hindin MJ. The effects of unintended pregnancy on infant, child, and parental health: a review of the literature. Stud Fam Plan. 2008;39(1):18–38.

Kost K, Lindberg L. Pregnancy intentions, maternal behaviors, and infant health: investigating relationships with new measures and propensity score analysis. Demography. 2015;52:83–111.

Faisal-Cury A, Menezes PR, Quayle J, Matijasevich A. Unplanned pregnancy and risk of maternal depression: secondary data analysis from a prospective pregnancy cohort. Psychol Health Med. 2017;22(1):65–74.

Tilahun G, Degu G, Azale T, Tigabu A. Prevalence and associated factors of timely initiation of breastfeeding among mothers at Debre Berhan town, Ethiopia: a cross-sectional study. Int Breastfeed J. 2016;11:27.

Adhikari M, Khanal V, Karkee R, Gavidia T. Factors associated with early initiation of breastfeeding among Nepalese mothers: further analysis of Nepal demographic and health survey, 2011. Int Breastfeed J. 2014;9:21.

Vieira TO, Vieira GO, Giugliani ER, Mendes CM, Martins CC, Silva LR. Determinants of breastfeeding initiation within the first hour of life in a Brazilian population: cross-sectional study. BMC Public Health. 2010;10:760.

Karim F, Khan ANS, Tasnim F, Chowdhury MAK, Billah SM, Karim T, et al. Prevalence and determinants of initiation of breastfeeding within one hour of birth: an analysis of the Bangladesh demographic and health survey, 2014. PLoS One. 2019;14(7):e0220224.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to the UNICEF MICS team for providing us with the data.

Funding

Authors were not funded.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

PAA conceived the study and analyzed the data. PAA and MTK wrote the manuscript and approved the final version for submission.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study did not require ethics approval as we used secondary data which is publicly available. Details of ethics approval for MICS is available at: https://mics.unicef.org/tools.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

Authors have no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

This article has been retracted. Please see the retraction notice for more detail:https://doi.org/10.1186/s13006-021-00362-8

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Apanga, P.A., Kumbeni, M.T. RETRACTED ARTICLE: Prevalence and predictors of timely initiation of breastfeeding in Ghana: an analysis of 2017–2018 multiple indicator cluster survey. Int Breastfeed J 15, 91 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13006-020-00335-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13006-020-00335-3