Abstract

Background

We undertook ethnobotanical and ecological studies on fodder plants grazed by cattle across Benin national area. The study aims to ascertain the top priority fodder plants in order to catalogue the indigenous knowledge regarding their use.

Methods

Data were collected through semi-structured interviews and covered 690 breeders and 40 days of pasture walk. These were analysed using similarity index of Jaccard (IS), relative frequency citation (RFC) and fodder value during pasture walk (FVPW).

Results

We documented a total of 257 fodder plant species, of which 116 recorded during ethnobotanical investigations and 195 during pasture walk. These species belong to 181 genera and 54 families. Both methods shared 52 species. Leaves (58%) and leafy stem (28%) were the most grazed parts of plant. The most common species used as fodder included Andropogon gayanus, Panicum maximum, Pterocarpus erinaceus and Flueggea virosa. The top species with a highest FVPW were Panicum maximum and Pterocarpus erinaceus. A total of 16 species were considered as top fodder plants in Benin.

Conclusions

The wide diversity of plants reported indicates that there is a number of promising fodder species in the flora of Benin. The insight gained in this study relating to bovine feeds could guide in the selection and introduction of feed innovations that could improve livestock production.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Worldwide, indigenous knowledge about the uses of plants as fodder or medicine played an important role in animal breeding development. Animal breeding is an ancient practice that represents an important subsistence source for low-income households worldwide [1]. In Benin, this activity plays an important role in the local economy and contributes to maintaining rural areas’ activity, their involvement in environment’s quality and poverty alleviation [2]. The considerable headway made in the field during recent decades, in particular the respect of schedules of vaccination campaigns becoming more and more rigorous, breeder awareness and their training on alimentation and the sanitary security of their cattle, and the increase of the credits allocated to them, have led to the steady growth of livestock production. From 1994 to 2013, livestock inventory in Benin increased by 39.18% for cattle and 35.40% for sheep and goats according to the FAOSTAT official database (http://www.fao.org/faostat/en/#home). Unfortunately, livestock sub-sector is still confronted by feeding problems [3], related to the availability and the quality of fodder resources. Indeed, natural pastures constitute the basis and, in most cases, the total food resources of ruminants. These pastures are in the majority dominated by annual plant species, characterised by a short development cycle that entirely unrolls in rain season. In this period, pasture contributes to ensure feed of cattle, but during the dry season, the longest season, it exists only the straws which are qualitatively poor and quantitatively deficient [4]. Although Benin is characterised by a vegetation type diversity [5], environmental pressures and strong influence of climatic seasonality limit the productive and nutritional potential of the fodder resources and hinder to maintain flocks, especially during drought periods. So, many breeders devote oneself to the ligneous that dispose leaves and fruits with high protein contents.

To face the unfavourable situation to the breeding development, it is important to capitalise traditional knowledge about fodders. Understanding traditional knowledge of people will result in four major outputs: the database creation of fodder plants consumed by cattle, identification of their properties and optimisation of their uses. To these, we can add the selection of fodders with top priority in stock farming based on their use value. According to Nunes et al. [6], a combination of traditional and scientific knowledges could allow to optimise the selection of useful fodder plants.

Ethnobotanical investigations about ruminants fodder plants have been developed in African countries such as Ethiopia, Nigeria, Ghana and Uganda [7,8,9,10], and elsewhere in Asia, India and Mexico [6, 11,12,13]. In Benin, there is no overall documentation about the relative importance of these feeds to farmers, although some researchers reported on tree fodders or medicinal tree fodders browsed by ruminants on natural pasture in northern Benin [14,15,16]. This study aims to (i) document fodder plants of natural pastures and state farms in Benin, (ii) assess the local knowledge regarding their use and (iii) select the most important fodder plants. The results of this study will be used to provide a checklist of fodder resources for further anatomical investigation and a possible improvement of food diet in controlled stock farming in Benin.

Methods

Study area

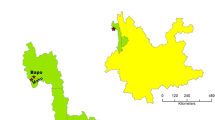

Study was conducted across national area of the Republic of Benin (Fig. 1), located in West Africa between the latitudes 6° 10′ N and 12° 25′ N and longitudes 0° 45′ E and 3° 55′ E. It is bordered by Togo in the west, Nigeria in the east, Atlantic Ocean in the south and Burkina Faso and Niger in the north. The fieldwork was carried out in 23 localities (Fig. 1) and 4 state farms described in Table 1.

The study zone is submitted to three climate types (subequatorial in the southern zone, transition between subequatorial and tropical in the centre zone and tropical climate in the northern zone). The mean annual rainfall fluctuates from 900 to 1400 mm. The vegetation grows under three climate zones. According to Adomou [17], the southern zone consists of savannah, grassland, farmland and fallow intermingled with small islands of closed forest (semi-deciduous and swamp forests). In the centre and northern zones, the natural vegetation is essentially made of a patchwork of woodlands and savannahs with belts of riparian forest along rivers.

The national area contains 2807 plants species belonging to 1130 genera and 185 families [18]. The population of the country was estimated at 9,983,884 inhabitants with the majority involved in agriculture and breeding [19]. The livestock are mainly cattle (2,005,000), sheep and goats (2,413,000), pigs (293,200) and birds (15,900,000) [20]. The cattle production is concentrated at 85% in north of the country and largely dominates those of other animals [21]. The composition of cattle herds is characterised by a predominance of cows which expresses the dairy and breeding vocation that breeders give them. There are two general types of traditional cattle production in Benin: sedentary production in the Guinean region, which accounts for about 20% of the national herd, and transhumant production, which accounts for the other 80%. The exploitation of cattle is based on natural pastures and crop residues [22]. The Peulh own 95% of the national cattle herd and are thus the essential actors for the supply of animal proteins from the country [23].

Data collection

We coupled ethnobotanical study and pasture walk for the data collection. During ethnobotanical investigations, 690 livestock owners were identified with the assistance of specialised animal production technicians for their experience in traditional breeding. Between February 2016 and May 2017, we conducted semi-structured individual interviews using 30 questionnaire slips per locality. The topics covered by the interview were socioeconomic parameters (ethnic group, sex, age, education level, profession, breeding type, size of livestock and source of knowledge) and fodder plants consumed by cattle (wild or crop, preference, parts of plants, collect modes and season of use).

In this paper, we use the term “fodder” to indicate plants grazed by the animals directly on pasture lands and those cut and carried to them. It includes grasses, cereal crops, legumes, shrubs and trees.

The pasture walk was authorised by the Coordinator of PAFILAV (Programme d’Appui aux Filières Lait et Viande) that ensures the management of state farms. It was conducted on the 4 state farms, and the data were recorded following the season (Table 2). On each farm, one herd and one animal were randomly selected by specialised animal production technician regarding state health of cattle. The pasture walk consisted of following the herd in natural vegetation neighbouring the farm between 9:00 am and 5:00 pm and to record plant species consumed by the targeted animal. The observations were repeated during 5 days.

Data analysis

Assessment of the taxonomical diversity

The data were organised, summarised and analysed using Excel spreadsheets. All species cited by informants and those recorded during pasture walk were identified using the Analytic Flora of Benin [18] and at the National Herbarium of Benin by comparing with already identified herbarium specimens. Voucher specimens of these plants were kept at the National Herbarium. A value of genus coefficient (GC) was determined by dividing the total number of species over the number of genera. In this study, recorded fodder flora presents high genus diversity when GC ≥ 1. Therefore, when GC < 1, this denotes low genus diversity.

The similarity index of Jaccard (IS) was calculated, and the similarity in fodder species composition between the pasture walk and the survey was compared following Kent and Coker [24]. IS was calculated as follows:

where, a is the number of species found only in rangelands, b is the number of species only cited in survey and c is the number of common species in pasture walk and survey. Finally, IS was multiplied by 100 to calculate the percentage similarity in species composition between pasture walk and survey.

Breeders’ knowledge assessment

The difference in richness of grazed species during the drought and rain seasons was found through the chi-square test. The relative frequency of citation (RFC) and percentage of fodder value during pasture walk (FVPW) of each species were calculated.

Relative frequency of citation (RFC) was determined by dividing the number of informants citing a fodder species (FC) by the total number of informants in the survey (N). RFC was calculated by the formula as described:

The FVPW corresponds to the number of times a species was grazed by the target animal bovine during pasture walk.

A regression procedure was used to examine the correlation between RFC and FVPW. The Pearson correlation coefficient was used for this. Species present on rangelands and having RFC values higher than the mean of RFC were considered as priorities among fodder plants consumed by cattle in Benin.

Results

Taxonomical, morphological and habitat’s diversity of recorded fodder plants

A total of 257 fodder plants of which 116 for ethnobotanical investigations and 195 for pasture walk, with 52 common species, were recorded as consumed by cattle in Benin. These belong to 181 genera and 54 families. The average number of species recorded per family was 4.78, with 8 families (14.61% of the total) having more species than the average (Table 3). The 10 families that contributed 72.86% of all species were Leguminosae, Poaceae, Euphorbiaceae, Combretaceae, Asteraceae, Rubiaceae, Malvaceae, Moraceae, Acanthaceae and Amaranthaceae. The most speciose ones being Leguminosae (76 species, 29.45%) and Poaceae (57 species, 22.09%). These families were followed by Euphorbiaceae (12 species, 4.65%), Combretaceae (9 species, 3.48%), Asteraceae (9 species, 3.48%), Rubiaceae (7 species, 2.71%) and Malvaceae and Moraceae (6 species each, 2.37%). Twenty-seven families (50% of the total) were represented by only 1 species each. The remaining 27 families contributed between 2 and 5 species each (0.77–29.45% of the total). The ratio of the number of genera to the number of species was 1.41; we concluded high genera diversity among recorded species. The richest genera were Desmodium, Hypparhenia and Indigofera with 6 species each. The next most diversified genera in terms of species richness were Andropogon, Crotalaria (5 species each), Combretum, Ficus, Schizachyrium, Senna and Tephrosia (4 species each) followed by Acacia, Albizia, Brachiaria, Commelina, Pennisetum, Setaria, Sida, Terminalia and Vigna (3 species each). The low value of Jaccard’s similarity index (34%) means that the species harvested on pasture are distinct from those indicated by the breeders.

Only 38.74% of species are available during all seasons (perennial species). Concerning their life form, fodder plants include mostly herbs (58%). These were followed by trees (21%), shrubs (16%) and lianas (5%). The majority of these plants were wild (92%) followed by cultivated (5%) while about 3% were reported as wild or cultivated. Fallows and farmlands (79%) were habitat with high proportion of species. The remaining includes the savannah (16%), forest (3%), habitation and meadow (1% each).

Plant parts consumed

Even though major plant parts are significant in the bovine alimentation, leaves were the most commonly used plant part with 58% of citation (Fig. 2). It was followed by leafy stem (28%), flowers and fruits (4% each). However, whole plant was cited in 6% of cases.

Fodder value about recorded plants

The relative frequencies of citation (RFC) of 116 cited species are shown in Table 3. RFC varies from 1.12 to 5.81%, with 16 species having RFC higher than 1.38 (the average of RFC). Plant species such as Andropogon gayanus, Panicum maximum, Pterocarpus erinaceus and Flueggea virosa which were frequently cited were the four dominant plants used as cattle fodder by the breeders in Benin (Table 3). These were followed by Andropogon tectorum (RFC = 4.24%), Anogeissus leiocarpa (3.16%), Piliostigma thonningii (2.83%), Pseudocedrela kotschyii (2.57%), Prosopis africana (2.52%), Digitaria horizontalis (2.29%) and Annona senegalensis (2.21%). Those with the lowest citation frequencies included fodder plants such as Bambusa vulgaris and Vetivera nigritana (0.12% each).

Percentage of fodder value during pasture walk (FVPW) varied from 3% (52 species) to 50% (2 species) (Table 3). We established 3 groups according to the palatability of fodder: 16 highly palatable, 73 weakly palatable fodder and 113 fairly palatable plants (Table 3).

Selection of priority fodder plants consumed by cattle and their characteristics in Benin

Results from regression analysis showed a significantly positive correlation between relative citation of the species (RFC) and fodder value percentage during pasture walk (FVPW) (r = 0.814; p < 0.001). There was 66.66% of the variation of RFC that were explained by the variation of FVPW (Fig. 3). Species with higher RFC values often had higher FVPW and included Andropogon gayanus, Panicum maximum and Pterocarpus erinaceus.

We considered the 16 fodder plants having RFC higher than 1.38% (the average of RFC), as top fodder species in Benin (Table 4). According to local people, only 38% of them were highly palatable (Table 4).

Discussion

Diversity of recorded fodder species

Fodder plants consumed by cattle represent 9.01% of the flora of Benin reported by Akoègninou et al. [18]. Among them, only 23.23% are hold by breeders. This shows their low knowledge level about fodder resources. Locally, the clear distinction between the species harvested on pasture and those quoted by the breeders can be explained by the non-control of the plants by the breeders. In vegetation, they are not concerned about feeding cattle as the resource is available and do not continuously monitor the animals. Except in drought, due to lack of grasses, breeders make the choice to cut the branches of shrubs and trees to allow the animals to feed. This was the same on the farms where the drovers cut branches of species to facilitate grazing on the herd. Complementation of cattle diet in the dry season with woody leaves is a common practice in several tropical countries [25,26,27,28,29,30]. This technique makes it possible to provide supplements and to limit the decline in milk production, but the choice of a well-browsed and productive species is necessary [28]. Among species affected by this practice are Khaya senegalensis, Afzelia africana, Prosopis africana, Pterocarpus erinaceus, Leucaena leucocephala, Piliostigma thonningii, Acacia sieberiana, etc. The nutrient input of ligneous fodder is significant in quantitative terms, for reducing seasonal fodder shortfalls and maintaining the livestock, but it is not enough to significantly improve the nitrogen levels of diets, which is a production-limiting factor [29].

Specific richness obtained was 5.27, 10.12 and 1.70 times higher the numbers reported by Sèwadé et al., Sidi et al. and Sinsin et al. [15, 16, 31] respectively for fodder flora in the country. These differences would be due to the national scope of the present study and the combined effect of ethnobotanical studies and the transit walks, contrary to earlier work which covered only part of the country, the ethnobotanical investigations or based only on tree fodder inventory. On the other hand, if we compare our data with the number of fodder species reported outside Benin, specific richness appeared to be relatively higher or lower. César and Zoumana [32] reported 214 species consumed by cattle, sheeps and goats in savannahs of Côte-d’Ivoire. In southwest China [13] and northeast Brazil [6], it was respectively reported 143 and 136 fodder plant species consumed for cattle. These gaps can only be explained by the same arguments given above. Many of these plant species were widely exploited by livestock in other regions of Africa, for example Uganda, Kenya, Zimbabwe, Ethiopia, Nigeria, Rwanda and Mozambique [7, 33,34,35,36,37,38,39], and elsewhere in the world [6, 40]. They are species with important nutritious value for ruminants and highly used in cropping systems. We can cite Leucaena leucocephala, Panicum maximum, Andropogon gayanus, Imperata cylindrica, Pterocarpus erinaceus, Cynodon dactylon, Digitaria horizontalis, Anacardium occidentale, Mangifera indica, Anogeissus leiocarpus, Alchornea cordifolia, Chamaecrista rotundifolia, Eleusine indica, etc.

Among 185 plant families represented in Benin [18], 29.18% were recorded as fodder plant families. The most diversified in terms of species were Leguminosae and Poaceae. The importance of these families is not a particularity for the fodder flora, but it is a general characteristic of Benin flora because they respectively represent 14.8 and 9.3% among 2807 species [18]. Our findings suggested high genera diversity among recorded species. Thus, in a context of the species rarity, Benin flora provides the possibility to select a great number of fodder species.

Knowledge about recorded fodder species and use priority by local communities

Though the importance of Leguminosae and Poaceae among recorded plant families is related to the characteristic of Benin flora, this is prominent in the literature, and information regarding the potential productivity and nutritional value is abundant, mainly due to the preference of animals for these two families. Breeders, in permanent touch with their animals, accumulate concurrently day by day the experiences as well on zoo-technique plan as sanitary in order to improve their knowledge on the production and reproduction of animals. Thus, traditional knowledge about fodders of communities should build on the base of their observations and this is orally handed down through generations. Today, they have increased their knowledge and they select great fodders following two main criteria namely quality and availability during the dry season. When we asked factors determining fodder quality, they had cited the palatability, aptitude of the fodder to increase milk production, to treat cattle pathologies, and their ability to fatten cattle. As overall objective of breeders is to sustainably feed cattle in order to improve their production and reproduction, important fodders were selected on the base of these criteria. Indeed, our study revealed Benin breeders preferentially use 16 fodder species that should be considered as priorities. They mostly belong to Leguminosae and Poaceae; Leguminosae being classified as sweet and fattening plants while Poaceae classified as palatable and productive in other regions. These findings are consistent with many studies [9, 41,42,43]. Among the 16 priority species selected, some have already been identified by Sidi et al. [15] as priority fodder plants in northern Benin namely Pterocarpus erinaceus, Afzelia africana, Acacia sieberiana, Piliostigma thonningii and Flueggea virosa. These species were also reported in other regions (Sénégal, Cameroon, Niger, etc.) [25, 27, 28] as priority woody species used by pastoralists in Sudanian zone.

Trees and shrubs represented high proportion among fodders cited by local communities. The preference of breeders for these life forms should be due to their availability in all the seasons but also to the relative low contents of crude protein and some minerals in tropical grass species [6, 32, 44, 45].

The plant part used in animal feed is an important criterion of the nutritional [12, 46] and ecological [47] point of view. The widespread use of leaves for fodder in our study is in accordance with the findings of Ayantundé et al. [48] in southwestern Niger, where leaves are the most widely plant part used for fodder and traditional medicine by the agropastoralists.

Fodder species and sustainable production of cattle in Benin

We think that the valorization and sustainable utilisation of 16 priority fodders could help to improve the cattle production. Among these plants, breeders listed Afzelia africana, Acacia sieberiana, Prosopis africana, Piliostigma thonningii, Digitaria horizontalis, Leucaena leucocephala, Pterocarpus erinaceus, Flueggea virosa, Panicum maximum and Andropogon gayanus as forage providing important nutritional properties with high palatability. Literature informs that this nutritive value hold by these plants is due to their content in total nitrogenous substances, which are mostly important in L. leucocephala, P. erinaceus, A. africana, A. sieberiana, P. africana [48] and P. maximum and A. gayanus [49]. This makes these plants genuine protein banks for feeding of ruminants during the both seasons due to the presence of two types of fodders (annual and perennial). In addition, according to the breeders, some of these fodders hold many medicinal properties. Tephrosia purpurea was recognised as being efficiently used to treat helminthiasis, whereas Detarium microcarpum was cited to address several gastrointestinal disorders notably diarrhoea and constipation. Furthermore, breeders recognised P. africana and A. africana as plants involved in increasing of the production of milk after their grazing by the cow. This knowledge hold by local breeders comes from a deep relation between human and biological resources of its local environment. Volpato and Puri [49] showed the Sahrawi recognise in detail the relations between forage and the taste, smell or health and nutritional properties of camel milk because camel milk was the main output of camel husbandry and a staple food in the Sahrawi pastoral system. Currently, the valorization of the local knowledge related to these species needs further studies in particular phytochemical and pharmacological to confirm medicinal properties, as well as anatomical, to identify their anti-nutritional drivers’ content such as lignins, which block the digestibility of nitrogen in rumen.

Most of top fodders form a component of livelihood strategies in the country because they remain an important source of health care and constitute an essential basis in traditional medicine improvement. They are also valued for their timber and their trade importance. Unfortunately, the large combined and increasing demand for these plants and the consequent increase in the rate of collection negatively affected the wild populations of many species, to the point that some species are now considered to be threatened with extinction. Thus, 2 fodder species among 16 priorities (12.50%) were classified as endangered plant species according to the International Union for Nature Conservation (https://www.iucnredlist.org/) and Adomou et al. [5]. We will cite A. africana and P. erinaceus. This handicaps their sustainable use. Agroforestry species such as Vitellaria paradoxa and Khaya senegalensis benefit from particular management practices such as assisted natural regeneration, seeding or often sapling transplantation within the farmlands [50]. But some species as A. africana seems to be neglected [50]. Urgent conservation measures must be taken for ensuring their sustainability use in Benin.

Pasture production is traditionally unknown in Benin, but forage cultivation is done on national farms [51]. Cultivated fodders have been experimented with but are of little importance in smallholder stock rearing. Fortunately, some fodders are cropped in several state farms such as L. leucocephala, Brachiaria spp., P. maximum and A. gayanus. However, this does not fully ensure their fodder needs for livestock. So the development of a breeding program or improvement of the priority forage species on these farms should be considered. After a promising species has been identified, evaluated and developed into a cultivar by selection or breeding, the seed of the resulting cultivar has to be made available to farmers for testing and use.

Conclusion

The combination of ethnobotanical studies and transit walks constituted efficient means for the documentation of 257 fodder plants consumed by cattle in Benin. Specific richness obtained during transit walk demonstrates the importance of follow-up in identifying fodder plants. In addition, this paper provided the lifespan, life form, most commonly used parts for fodder, in palatability, status, and a listing of priority fodder plants. The 16 top priorities were considered as important fodder resources used in Benin. Further studies are needed including an anatomical evaluation of 16 fodder species consumed by cattle for assessing their digestive capacity.

Abbreviations

- Ann :

-

Annual

- C :

-

Cultivated

- D:

-

Dry season

- DR:

-

Dry and rainy season

- FEB :

-

State farm of Bétécoucou

- FEK :

-

State farm of Kpinnou

- FEO :

-

State farm of Okpara

- FES :

-

State farm of Samiondji

- Fl :

-

Flowers

- Fr :

-

Fruits

- FVPW:

-

Fodder value during pasture walk

- Le :

-

Leaves

- Leg:

-

Leguminosae

- LS :

-

Leafy stems

- MT:

-

Morphological type

- Per :

-

Perennial

- PP :

-

Plant parts

- R:

-

Rainy season

- RFC :

-

Relative frequency of citation

- Temp:

-

Temperature

- tub :

-

Tubercle

- W :

-

Wild

- WC :

-

Wild and cultivated

- WP :

-

Whole plant

References

FAO (Food and Agriculture Organization). State of the World’s forests. Rome: Food and Agriculture Organization; 2011. http://www.fao.org/docrep/013/i2000e/i2000e.pdf. Accessed 13 Sept 17.

Gbangboché AB, Hornick JL, Adamou-N’ Diaye M, Edorh AP, Farnir F, Abiola FA, et al. Caractérisation et maîtrise des paramètres de la reproduction et de la croissance des ovins Djallonké (Ovis amon aries). Ann Med Vet. 2005;149:148–60.

MAEP (Ministère de l’Agriculture, de l’Elevage et de la Pêche). Programme National d’Amélioration Génétique. Cotonou: MAEP; 2015. 362p

Ouédraogo S. Potentialités fourragères et essais d’amélioration de la valeur nutritive de trois ligneux fourragers: Piliostigma thonningii Schumach Mile-Redh, Piliostigma reticulatum (D.C.) Hoscht et Khaya senegalensis (Desr.) A: Juss. Mémoire de fin d’études pour l’obtention du diplôme d’Ingénieur du Développement Rural. Burkina-Faso: Université Polytechnique Bobo Dioulasso; 2006. p. 79.

Adomou AC, Agbani OP, Sinsin B. Plantes. In Protection de la Nature en Afrique de l’Ouest: Une Liste Rouge pour le Bénin. Nature Conservation in West Africa: Red List for Benin, Neuenschwander P, Sinsin B, Goergen G (eds). Ibadan: International Institute of Tropical Agriculture; 2011. p. 2146.

Okoli IC, Ebere CS, Uchegbu MC, Udah CA, Ibeawuchi II. Survey of diversity of plants utilized for feeding small ruminant feeding in southeastern Nigeria. Agriculture, Ecosystem and Environment. 2003;96:147–54.

Shenkute B, Hassen A, Assafa T, Amen N, Ebro A. Identification and nutritive value of potential fodder trees and shrubs in the mid rift valley of Ethiopia. Journal of Animal & Plant Sciences. 2009;22(4):1126–32.

Tabuti JRS, Lye KA. Fodder plants for cattle in Kaliro district. Uganda African Study Monographs. 2009;30(3):161–70.

Duku S, van der Zijpp AJ, Udo MJH. Household vulnerability and small ruminant benefits in the transitional zone of Ghana. Journal of Agricultural Extension and Rural Development. 2010;4(5):98–106.

Nahed J, Villafuerte L, Grande D, Pérez-Gil F, Alemán T, Carmona J. Fodder shrub and tree species in the highlands of southern Mexico. Anim Feed Sci Technol. 1997;68(3):213–23.

Nunes AT, Paiva de Lucena RF, dos Santos MVS, Albuquerque UP. Local knowledge about fodder plants in the semi-arid region of Northeastern Brazil. J Ethnobiology and Ethnomedicine. 2015;11:12.

Angami A, Gajurel PR, Rethy P, Singh B, Kalita SK. Status and potential of wild edible plants of Arunachal Pradesh. Indian J Trad Knowl. 2006;5(4):541–50.

Geng Y, Hu G, Ranjitkar S, Wang Y, Bu D, Pei S, et al. Prioritizing fodder species based on traditional knowledge: a case study of mithun (Bos frontalis) in Dulongjiang area, Yunnan Province, Southwest China. J Ethnobiol Ethnomed. 2017;13:24. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13002-017-0153-z.

Awohouédji DYG, Lesse P, Houinato M, Hounzangbé-Adoté S. Medicinal forage present in the natural pasture in Benin: review article. J Anim Prod Adv. 2013;3(11):301–10.

Sidi H, Guédou A, Yétongnon D, Awohouedji G, Babatoundé S. Most consumed ligneous forages in ruminant breeding on natural pasture in north of Benin. Sci J Environ Sci. 2015;4(3):89–96.

Sèwadé C, Azihou AF, Fandohan AB, Houéhanou TD, Houinato M. Diversité, priorité pastorale et de conservation des ligneux fourragers des terres de parcours en zone soudanoguinéenne du Bénin. Biotechnol Agron Soc Environ. 2016;20(2):113–29.

Adomou CA. Vegetation patterns and environmental gradients in Benin. Implications for biogeography and conservation. Wageningen University, Wageningen: PhD thesis; 2005. 133p

Akoègninou A, Van der Burg WJ, Van der Maesen LJG. Flore Analytique du Bénin. Leiden: Backhuys Publishers; 2006. 1034 p

INSAE. Recensement Général de la Population et de l’Habitat (Résultats Provisoires). Cotonou: MDAEP. INSAE; 2013. 8p

DE (Direction de l’Elevage). Annuaire statistique sur l’élevage. Cotonou: Direction de l’Elevage; 2010. p. 09–82.

Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO). Country Stat 2013. www.countrystat.org/home on 13/09/17.

Dehoux JP, Hounsou-Vè G. Productivité de la race bovine Borgou selon les systèmes d’élevage traditionnels au Nord-Est du Benin. World Anim Rev. 1993;74(/75):36–48.

Djènontin JA. Dynamique des stratégies et des pratiques d’utilisation des parcours naturels pour l’alimentation des troupeaux bovins au Nord-Est du Bénin. Bénin: Thèse Doct., Université d’Abomey-Calavi, Faculté des sciences agronomiques; 2010. p. 214.

Kent M, Coker P. Vegetation description and analysis. England: A practical approach. John Wiley Ltd; 1992.

Onana J. Les ligneux fourragers du Nord-Cameroun. 1. Inventaire et phénologie. Revue Elev Méd vét Pays trop. 1995;48(2):213–9.

Mureithi JG, Njunie MN, Muinga RW, Ali R, Thorpe W, Mwatate CD. Adoption of planted forage by smallholder dairy farmers in coastal lowland Kenya. Tropical grasslands. 1998;32:221–9.

Petit S, Mallet B. L’émondage des arbres fourragers : détail d’une pratique. Bois et forêts des Tropiques. 2000;270:35–45.

Ickowicz A, Mbaye M. Forêts soudaniennes et alimentation des bovins au Sénégal : potentiel et limites. Bois et forêts des Tropiques. 2001;270(4):47–61.

Bechir AB, Mopate LY, Kaboré-Zoungrana CY. Evaluation de la disponibilité saisonnière du fourrage ligneux en zone soudanienne du Tchad: cas du terroir de N’Guetté 1. Int J Biol Chem Sci. 2009;3(1):135–46.

Sarr O, Diatta S, Gueye M, Ndiaye PM, Guisse A, Akpo LE. Importance des ligneux fourragers dans un système agropastoral au Sénégal (Afrique de l’ouest) Revue Méd. Vét. 2013;164(1):2–8.

Sinsin B, Ahanchédé A, Kreiss M. Étude des pâturages naturels du Borgou: périmètre Nikki-Kalalé-Sègbana. Département de Production Animale et Agro-Nutrition. 1988 ; 89p.

César J, Zoumana C. Les régimes alimentaires des bovins, ovins et caprins dans les savanes de Côte-d'Ivoire, et leurs effets sur la végétation. Fourrages. 1999;159:237–52.

Mpairwe DR, Sabiiti EN, Mugerwa JS. Effect of dried Gliricidia sepium leaf supplement on feed intake, digestibility and nitrogen retention in sheep fed dried KW4 elephant grass (Pennisetum purpureum) ad libitum. Agrofor Syst. 1998;41:139–50.

Roothaert RL, Paterson R. Recent work on the production and utilization of tree fodder in East Africa. Anim Feed Sci Technol. 1997;69:39–51.

Dzowela BH, Hove L, Maasdorp BV, Mafongoya PL. Recent work on the establishment, production and utilization of multipurpose trees as a feed resource in Zimbabwe. Anim Feed Sci Technol. 1997;69:1–15.

El Hassan SM, Kassi AL, Newbold CJ, Wallace RJ. Chemical composition and degradation characteristics of foliage of some African multipurpose trees. Anim Feed Sci Technol. 2000;86:27–37.

Ibewiro B, Sanginga N, Vanlauwe B, Merckx R. Nitrogen contributions from decomposing cover crop residues to maize in a tropical derived savanna. Nutr Cycl Agroecosyst. 2000;57:131–40.

Niang AE, Styger GA, Hoekstra D, Coe R. Fodder quality improvement through contour planting of legume-shrub/grass mixtures in croplands of Rwanda highlands. Agrofor Syst. 1998;39:263–74.

Muir JP, Alage A. Seasonal herbage production from two range types in southern Mozambique. African Journal of Range & Forage Science. 2001;18:37–41.

Harun N, Chaudhry AS, Shaheen S, Ullah K, Khan F. Ethnobotanical studies of fodder grass resources for ruminant animals, based on the traditional knowledge of indigenous communities in Central Punjab Pakistan. J Ethnobiol Ethnomed. 2017;13:56. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13002-017-0184-5.

Osuji PO, Odenyo AA. The role of legume forages as supplements to low quality roughages - ILRI experience. Animal Feed Science Technology. 1997;69:27–37.

Awan KH, Ranjha AM, Mehdi SM, Sarfraz M, Hassan G. Response of rice line PB-95 to different NPK levels. Online J Bio Sci. 2003;3:157–66.

Lenné JM, Wood D. Is there a logic of fodder legumes in Africa? Food Policy. 2004;29:565–85.

Paterson R, Karanje G, Nraata O, Kariuki I, Roothaart R. A review of tree fodder production and utilization with in smallholder agroforestry system in Kenya. Agrofor Syst. 1998;41:181–99.

Bussman RW, Sharon D. Traditional medicinal plant use in Northern Peru: tracking two thousand years of healing culture. Ethnobiology and Ethnomedicine. 2006;2:47.

Naruhashi N, Nepalese R. V international symposium on Rubus and Ribes 262. 1989.

Dao Z, Long C, Liu Y. Preliminary study on plants used by Nu people in Gaoligongshan area, Yunnan. Biodivers Sci. 2003;11(3):231–9.

Ayantundé AA, Hiernaux P, Briejer M, Udo H, Tabo R. Uses of local plant species by agropastoralists in South-western Niger. Ethnobot Res Appl. 2009;7:053–66.

Volpato G, Puri RK. Dormancy and revitalization: the fate of ethnobotanical knowledge of camel forage among Sahrawi nomads and refugees of Western Sahara. Ethnobot Res Appl. 2014;12:183–210.

Balima LH, Nacoulma BMI, Ekué MRM, N’Guessan Kouamé F, Thiombiano A. Use patterns, use values and management of Afzelia africana Sm. in Burkina Faso: implications for species domestication and sustainable conservation. J Ethnobiol Ethnomed. 2018;14(23) https://doi.org/10.1186/s13002-018-0221-z.

Gruber I. The impact of socio-economic development and climate change on livestock management in Benin. Inaugural- Dissertation zur Erlangung des Grades Doktor der Agrarwissenschaften (Dr.agr.) der Hohen Landwirtschaftlichen Fakult ¨ at der Rheinischen Friedrich-Wilhelms-Universit ¨ at zu Bonn vorgelegt am 11. 2007. http://hss.ulb.uni-bonn.de/diss_online/.

Acknowledgements

We thank the agents of regional action centres for rural development (CARDER) and state farmers for their outstanding assistance in the conduct of ethnobotanical surveys and pasture walk. We also acknowledge the breeders and farmers who welcomed us and facilitated the investigations and sir Abraham Favi for his assistance for making the map of the study area.

Funding

The authors received no specific funding for this work.

Availability of data and materials

All datasets on which the conclusions of the paper rely made available in the manuscript. The voucher specimens are kept at the Laboratory of Botany and Plant Ecology at National Herbarium of Benin and will be available upon request.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

OJMAS, DGH and AAC conceived and designed the research. OJMAS collected the data. AAC and YF provided the botanical identification of the species. OJMAS, DGH and AAF analysed the data. OJMAS wrote the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

All farmers and breeders gave their consent before conducting the interview. The pasture walk was authorised by the Coordinator of PAFILAV (Programme d’Appui aux Filières Lait et Viande) that ensure the management of state farms.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Ouachinou, J.MA.S., Dassou, G.H., Azihou, A.F. et al. Breeders’ knowledge on cattle fodder species preference in rangelands of Benin. J Ethnobiology Ethnomedicine 14, 66 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13002-018-0264-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13002-018-0264-1