Abstract

Nutritional disorders are now spreading worldwide both in developed and developing countries. Body image ideals and dissatisfaction have been linked to a number of poor health outcomes, including nutritional disorders. While previous studies have offered insight into weight status and body image perception of immigrants in North America, very few studies have analysed these aspects in migrants from Africa to Europe. Our review examines the effects of the migration process on beauty ideals and body dissatisfaction in African immigrants in Europe compared to residents in their own countries. The PubMed, PsycINFO and Google Scholar databases were searched for studies published from January 2000 till November 2015. Of the 730 titles identified, 26 met the inclusion criteria and were included in the present review. Among African residents, the body preferences depend on the country of residence and their socio-cultural status. Ethnic groups living in great isolation or with low incomes still have an ancestral idea of beauty, preferring a shapely body. However ethnic groups living in urban areas are moving toward Westernization of beauty ideals, preferring underweight or normal weight bodies. This review highlights that both residents and migrants are at high risk of nutritional disorders due to the adoption of Western beauty ideals. The results suggest that body dissatisfaction and BMI are increasing from Southern Africa to Europe according to a geographical gradient (described for females by Spearman’s coefficient and linear regression, respectively). We emphasize the need for monitoring of the weight and psychological status of immigrants and the development of specific preventive strategies in European countries.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

A wide body of research has described the relationships between health and weight status in different populations and environmental contexts. The categorization of weight status by BMI is a simple way to estimate underweight or overweight for a given height for general assessment of health status in a population. The increasing incidence of overweight and obesity worldwide is now reaching alarming proportions. As an effect of the nutritional transition, these diseases concern both developed and developing countries. Hence the latter are facing a dual burden of malnutrition, with a high prevalence of both underweight and overweight/obesity [1–3].

Body image perception is one of the psycho-social factors that can affect the weight status. As a consequence of a misperception, thin people might overestimate their weight and, conversely, many overweight/obese people are unaware that their body weight is too high. In such cases, as well as in case of dissatisfaction with one’s body image, there is often an association with weight-related behaviors [2, 4].

The relationship between weight status and body self-perception is also influenced by others factors such as cultural and social factors [5–8]. Previous studies in Western countries have reported lower accurate perceptions of overweight in low socio-economic status (SES) groups and this misperception contributes to the persistence of unhealthy lifestyle [9, 10]. This aspect is particularly burdensome in immigrants who, misperceiving their overweight/obesity, do not attempt to lose weight, leading to an increase of these nutritional disorders. Furthermore, people from low-to-medium-income countries who have migrated to high-income countries seem to be more susceptible to overweight and obesity than their local counterparts [11]. In addition, overweight and obesity among immigrants appear to increase significantly with time after migration, with rates approaching or overtaking those of the host population [12]. The process of “acculturation” leads to great changes in the “hosted” group, influencing diet and favouring the adoption of obesogenic behaviours [13, 14].

However, this process is not uniform across all immigrant groups and depends on ethnicity, gender, age at the time of migration and period of residency in the new country [15, 16]. Since socio-cultural factors influence the standards of desirable body weight within cultures, body image perception and body shape preferences are culturally determined [5]. Furthermore, the ideals of beauty may change as a result of immigration, leading immigrant people, especially women, to pursue ideals of thinness. Thus, in immigrants in which the beauty ideals determine an increased level of dissatisfaction, the risk for the development of nutritional disorders increases.

As is the case of immigrants, the comparison of body image perception and body shape preference across populations living in developing countries is complicated by the variety of environmental and cultural conditions. However, the diffusion and subsequent adoption of Western ideals of thinness also in these countries can affect changing body ideals of populations and thus their lifestyle, diet and physical activity patterns. This is related to ‘modernization’, media influence and recent rapid transitions of the economy and urbanization [17–19]. Nevertheless, it is not so clear if the recent preference for slimmer body size is only due to the Westernization process. It is also probably related to the idea that “plumpness” is revered only when it is a rare condition in a context of food scarcity, while it loses desirability when overweight and obesity become more prevalent [17].

Body size and body image perception have mainly been investigated among immigrant groups in the USA [11] and there are few data regarding migrants from Africa to Europe.

In this review we evaluate body dissatisfaction and weight discrepancy among African immigrants in Europe compared to people still living in Africa, tracing a pattern of geographical variation where possible.

Furthermore, specific aims included: to compare body image perception in different population samples from the same country; to compare body image perception between women and men; to consider how weight status interacts with body image perception. The changing self-perception among immigrants entails new challenges in Europe for the development of appropriate strategies aimed at ethnic groups more at risk for nutritional disorders.

Methods

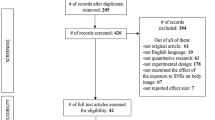

An extensive search for publications regarding body image perception and body size preferences in different ethnic groups from Africa, both in their countries of origin and after their migration to Europe, was carried out with Web-based search engines (PubMed and PsycINFO). Further searches were carried out in the search engine Google Scholar. In particular, experimental or review articles published from January 2000 to November 2015 were screened by one author (NR) on the basis of titles and abstracts. The inclusion of the full-text studies was then decided by all authors. A combination of the following key words was used for literature identification: “immigration”, “immigrants”, “migrants”, “refugees”, “ethnic minorities”, “body size preferences”, “body dissatisfaction”, “body image dissatisfaction”, “body image”, “weight”, “weight perception”, “Europe”, “Africans”, “North Africa”, “Central Africa”, “Southern Africa”.

In addition, the reference lists of all the selected articles were examined to find other non-indexed papers. In the selection, we took into consideration only cross-sectional studies with samples of healthy subjects aged 15 years or more; longitudinal studies, case reports or studies of subjects in childhood or with concomitant diseases (i.e. diabetes) were excluded. In total, 730 records were found, both through database and references searching, and 582 records were screened after duplicates removal. A number of 36 full-text articles were assessed for eligibility. After the omission of four studies on samples of too young or unhealthy subjects, three studies without body image outcomes and other three studies not focused on African migrants in Europe or on African residents, we included in this review 26 full-text papers (Fig. 1). A summary sheet was developed for extracting data including qualitative or quantitative methodologies to assess body image perception; sample size; age, gender and nationality of participants; host country; body mass index (BMI); prevalence of overweight and obesity (according to WHO cut-off points); actual and ideal figures, level of dissatisfaction. As there are few articles available in the literature on this topic, we considered all of them, irrespective of sample size, for a general listing.

Most of the considered studies classified subjects into weight categories by BMI. In some cases, height and weight were self-reported by the participants. There was wide variability among studies regarding the methods used for the evaluation of body image perception (silhouettes developed by different authors; self-reported questionnaires). In some studies, the Feel minus Ideal Difference index (FID) [20] representing the discrepancy between the actual figure and the ideal figure, was reported as the level of body image dissatisfaction, while in other studies the percentage of satisfaction, or of dissatisfaction (desire to lose/gain weight), was indicated.

An evidence synthesis was carried out by weighted means and pooled standard deviation (SD) of FID and BMI for African residents and immigrants in Europe to check for any trend. Only aggregations of data from studies reporting both BMI and FID for samples ≥ 50 subjects were considered for this purpose. According to the inclusion criteria, only female samples were considered. Linear regression analysis and Spearman R coefficient were carried out to estimate the geographical patterns on the basis of the weighted means of BMI and FID, respectively. For calculation purposes, the geographical areas were identified by numbers 1 (Southern Africa), 2 (Central Africa), 3 (North Africa) and 4 (African immigrants to Europe). Comparisons of mean BMI values between independent samples were carried out by Student’s t-test.

The results were statistically significant when p was <0.05. The statistical analysis was carried out using STATISTICA for Windows, Version 11.0 (StatSoft Italia srl, Padua, Italy).

This review was carried out in accordance with the PRISMA guidelines [21].

Results

Description of included studies

Twenty-six studies were included in this review on the basis of available data on samples of African origin living in Europe (EU) or still in their own countries (Table 1). Six of them were carried out on body image and body size ideals of Africans who had migrated to EU: three on North African (NA) immigrants in the Netherlands [18, 22, 23], one on NA immigrants in Italy [24] and two on Southern African (SA) immigrants in the UK [25, 26]. For the comparison with their peers still resident in Africa, we utilized studies on Moroccans, Tunisians, Egyptians [17, 22–24, 27–33] and people living in Zimbabwe and South Africa [2, 25, 26, 33–38]. Unfortunately, no study was found on Central African (CA) immigrants in EU. However, for completeness and comparative purposes, we report data for residents in this area [4, 33, 39–43] in order to have a full picture of body image perception and dissatisfaction throughout Africa.

Studies on North Africans

Nicolau et al. [22] focused on body size preference and body size perception of Moroccan immigrants in the Netherlands (Amsterdam), reporting that most Moroccan women wished to be thinner than they were (Table 1). The majority of Moroccan men were unaware of being overweight. Another two studies [18, 23] found that both female Moroccan immigrants in the Netherlands and residents in Morocco expressed a preference for thin and normal body size. Many of them wished to lose weight.

Research on NA immigrant women in Italy compared to Moroccan and Tunisian residents in their countries [24] suggested that there were great similarities in the ideal figure among NA immigrant women and Tunisian residents while Moroccan residents tended to prefer a heavier ideal figure. Body image dissatisfaction was slightly (albeit not significantly) higher in NA immigrants (FID: 1.99 ± 2.31) than in NA residents (Moroccans FID: 1.50 ± 1.83; Tunisians FID: 1.40 ± 2.41).

As regards NA residents, misperception of body weight [30] and a preference for fat body size [27, 28] were reported in three studies on Moroccan populations (Table 1). In particular, despite their high percentage of normal weight and overweight, Amazigh men and women from the High Moroccan Atlas underestimated their body mass and wished to gain weight [30]. Moroccan Saharoui women [27, 28] were generally satisfied with their body weight (almost 80 % satisfaction) in spite of the high prevalence of overweight and obesity, with a small percentage of them wishing to gain weight and an even lower percentage wishing to lose weight. Moroccan women living in Casablanca [29] had a high percentage of overweight and obesity, but most of them were not aware of their body size: about half of the normal weight women considered themselves too thin, while most of the overweight and obese women considered themselves “normal weight”. Another study taking in consideration Moroccan women living in Casablanca [24] reported that they were aware of their body size but they are dissatisfied because they wanted to be thinner. Also Egyptian university students were dissatisfied with their body weight, especially women [31, 32], which is consistent with the results obtained by Gualdi et al. [24] and by Nicolau et al. [23] on NA residents. In Tunisia, Tlili et al. [17] reported that over half of the women in a peri-urban area of Tunis were dissatisfied with their body weight, with most of them preferring a lighter ideal body size and a smaller proportion wanting a heavier one. Moreover, the majority of overweight and obese women preferred a slimmer silhouette. A normal body size was generally seen in the most positive light, although some positive attributes were associated with overweight. An association between BMI or body size preferences and age or level of education was found in this study [17]. Consistently with these results, the young Tunisian men and women examined by Jaeger et al. [33] and Tunisian women examined by Gualdi-Russo et al. [24] were aware of their body size (normal weight or slightly overweight), but they wished to be thinner.

Studies on Central Africans

As already mentioned, no studies were found regarding CA immigrants in EU. However, in order to have a complete picture of body image perception and beauty ideals in Africa, we included five studies on CA residents from different countries in Table 1. Three of them considered Ghanaian women, reporting their preference for a slightly overweight or normal weight body shape and rather low level of FID [4, 33, 39]. The studies of Frederick [4] and Benkeser et al. [39] found that, unlike normal weight Ghanaian men and women studied by Jaeger et al. [33], there was a misperception of their weight status since, despite their obesity status (according to BMI), they saw themselves as overweight [4, 39]. Siervo et al. [40] reported that Gambian men and women had a preference for overweight body shapes. In particular, the oldest group of men and women wanted to be fatter. Higher body dissatisfaction emerged only in the oldest group of females, since they were aware of being obese and wanted to be slightly slimmer. Senegalese women generally had a good perception of their body [41], showing only slight body dissatisfaction because their ideal was a little slimmer than their actual figure (slightly overweight). Both male and female residents in Nigeria and Gabon had, on average, low levels of FID and a normal BMI. They had good perception of their body and a preference for normal body size [33, 42]. Moreover, the majority of Nairobi slum residents were in normal weight with a tendency for men to overestimate their body size and for women to underestimate it. Unlike men, women had low levels of dissatisfaction with a preference for normal body size [43].

In general, CA residents showed a preference for normal or slightly overweight body size, with a rather low level of dissatisfaction with their body.

Studies on Southern Africans

Two studies of SA migrants in EU reported the results for Zulus and Zimbabweans who had migrated to the UK [25, 26]. Both groups of immigrants wanted to lose weight and had general preferences for normal weight body size. The female Zimbabwean immigrants in the UK [25] had a more negative body image perception than their peers in Zimbabwe and their level of dissatisfaction was very high. They reported a greater weight discrepancy because they saw themselves as larger than they were to a greater degree than the Zimbabwean residents and they wanted a thinner body size. Instead the Zimbabwean women living in Zimbabwe still held to an ancestral idea of beauty, preferring a heavier body [25]. In Tovée’s study [26], there were substantial differences in the perception of female attractiveness in the different groups of immigrants examined. The peak of attractiveness for Zulus resident in South Africa shifted to a higher BMI, while for Zulus who moved to Britain (Female ideal BMI: 23.99) it seemed to be intermediate between those of their peers living in South Africa and Britons of African descent.

Five studies reported results for SA residents in urban (Cape Town) and rural (KwaZulu-Natal) areas [2, 33, 34, 36, 37]. Both rural and urban groups wished to lose weight but the greatest body discrepancy was among the urban residents, who preferred normal weight figures in contrast to the rural inhabitants who preferred an overweight body shape. Additionally, other two studies [35–38] found the presence of body dissatisfaction among South African residents in urban and rural areas, with normal weight men and women slightly overestimating their body weight.

Summary and general geographical pattern

In order to clarify the complex picture emerging from the literature, this paragraph provides a summary (Table 2) of the main results examined in detail above. It is organized around the main aims of this study focusing on weight status and body image perception in African residents and immigrants, compared to European populations, when possible.

To acquire a synthetic overview of body image perception in people with an African origin, we considered resident and immigrant African samples, combining the data from several studies for the following geographical areas: Southern Africa, Central Africa, North Africa, EU (immigrants from Africa). This analysis was possible only for females (Southern Africa: 140 Zimbabwes from Swami et al., 2012 [25]; Central Africa: two Gambian samples differently aged, 50 subjects each, from Siervo et al. [40]; North Africa: 124 Moroccans and 104 Tunisians from Gualdi-Russo et al. [24]; EU: 138 Zimbabwe immigrants to UK from Swami et al. [25] and 105 NA immigrants to Italy from Gualdi-Russo et al. [24]. Figure 2 shows the linear relationship between BMI and the geographical areas (statistically significant). The FID also increased significantly with the geographical gradient (Spearman R = 1). The mean increase in BMI was 0.53 kg/m2 per unit increase in geographical area (Fig. 2).

A different trend emerged for North Africa and Southern Africa (Fig. 3) when immigrants were compared with residents in the country of origin: SA immigrant women had higher values of FID than SA residents, but similar BMI values; NA immigrant women had significantly higher values of BMI (p < 0.05) than NA residents, but similar values of FID.

Discussion

In many non-Western and low-income countries, body fat is seen as an indicator of health and prosperity since only high-status individuals have the possibility to put on body weight because of the scarcity of food. Conversely in many industrialized countries with a food abundance, fatness is associated with poverty and poor health [17] while slimness is a sign of high economic status [44]. A recent study of South Africans [45] revealed that overweight women underestimate their size and have an inappropriate perception of the risk of the obesity. However, it was suggested that the degree of preference for plumpness in non-Western societies has been exaggerated by Western studies and that the fear of fatness is more likely to be expressed in those who have had a greater exposure to Western culture [46].

During the complex immigration process, everything that surrounds the person changes, including the diet, social and family relationships, climate and culture [47]. Factors such as acculturation, enculturation and socio-economic status (SES) have a strong effect on many parameters, including weight status and perception of body size.

The data analysis in the present review revealed a wide variability of body weight/image perception in Africa: African residents generally showed a preference for heavier body size than their immigrant peers, but differences in preferences were evident in relation to the area of residence, ethnicity, and social and cultural factors even in the same population (i.e. Moroccans). Similarly, in a longitudinal study on changes in body composition of black urbanised South African women [48], the presence of two different groups of overweight/obese women was highlighted: one group, more aligned with Western values, wished to be thinner and the other one, more aligned with the African values, was content with its body size.

Some of the considered ethnic groups desired a thinner body image while others held to the idea that higher body weight is a positive factor. This puts the latter groups at higher risk of obesity and the maintenance of it over time. A high level of body size dissatisfaction can lead to eating disorders and poor eating habits.

Hence this review shows that there is a different awareness of weight among the examined groups, with different consequences for health and well-being.

We found in the analysis of general geographical pattern that the body image dissatisfaction (FID) increased with the increase in BMI from south to north, reaching the highest values in African immigrants in EU, who also had the highest values of BMI (on average, above the cut-off of overweight). These results indicate different beauty ideals of African populations and thus different degrees of satisfaction in the perception of their body image from Southern Africa to North Africa and, to a greater degree, with the migration to Europe. In addition to differences in ideals, there were changes in weight status, which increased from Southern Africa to North Africa and to EU.

The differences, for example, between Zulu immigrants and those resident in South Africa were explained in terms of adaptation to a new environment [26]. The adaptation to the new environment was supported by the comparison between UK Africans and UK Caucasians (BMI: 20.85) since both preferred medium BMI values. The beauty ideals of the immigrants became similar to those of the host Western population and increased the level of dissatisfaction, placing them at greater risk for the development of a negative body image and eating disorders [25].

There are some limitations to this review. Our synthesis of the African trend according to a geographical gradient is limited by the uncertainty involved in the data used to calculate the mean values of FID and BMI for each area. This uncertainty relates to the fact that only a few countries and small samples were available for each area. Another limitation of the review is the variety of methods utilized to assess body image and body size preferences, so that a comparison between different studies is difficult. Many authors did not utilize appropriate silhouettes for their studies or used self-administered questionnaires without figural references. Some studies were based on self-reported height and weight and this could result in an incorrect estimate of the BMI. Moreover, the studies did not report the same information, often overlooking one or more data (i.e. actual self-perception or the ideal body size). Nevertheless, due to the scarcity of studies focusing on body image perception and body size ideals in immigrants in Europe, we considered necessary to include all the studies reported in the literature in this review. Finally, only a few studies considered individuals of both sexes and the majority of them focused on female body shape or did not separate the results between the two sexes.

Conclusions

Although there are still few specific studies reported in the literature, our review is a good starting point to evaluate body image perception and body ideals in populations of African origin. The results for African immigrants in Europe suggest that body dissatisfaction is increasing with respect to populations living in the country of origin. There is a tendency to a simultaneous increase in BMI and a decrease in FID from Southern Africa to North Africa and Europe.

Therefore, the results highlighted in this review are evidence of preferences for slimness during the process of acculturation (for immigrants) and, more in general, of Westernization, involving greater body dissatisfaction and the risk of nutritional disorders.

The availability of local data on body image perception is essential to plan health strategies and to support non-communicable disease management. Continued monitoring of how the perception of body image is evolving, with a check of the changes of weight ideals over time, should be a primary health goal to ensure psychological well-being and health among immigrants in Europe.

Abbreviations

BMI, body mass index; CA, Central African; DIS, dissatisfied; EU, Europe; FID, feel minus ideal difference index; NA, North African; NW, normal-weight; OB, Obese; OW, Overweight; SA, Southern African; SAT, Satisfied; SD, Standard deviation; SES, Socio-economic status; UW, Underweight

References

Ng M, Fleming T, Robinson M, Thomson B, Graetz N, Margono C, et al. Global, regional, and national prevalence of overweight and obesity in children and adults during 1980–2013: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2013. Lancet. 2014;384:766–81.

Swami V, Frederock DA, Aavik T, Alcalay L, Allik J, Anderson D, et al. The attractive female body weight and female body dissatisfaction in 26 countries across 10 world regions: results of the international body project I. Pers Soc Psychol Bull. 2010;36:309–25.

Gualdi-Russo E, Zaccagni L, Manzon VS, Masotti S, Rinaldo N, Khyatti M. Obesity and physical activity in children of immigrants. Eur J Pub Health. 2014;24 Suppl 1:40–6.

Frederick. Female body dissatisfaction and perceptions of the attractive female body in Ghana, the Ukraine, and the United States. Psychological Topics. 2008;17:203–17.

Paeratakul S, White MA, Williamson DA, Ryan DH, Bray GA. Sex, Race/Ethnicity, Socioeconomic Status, and BMI in Relation to Self-Perception of Overweight. Obes Res. 2002;10:345–50.

Mama SK, Quill BE, Fernandez-Esquer ME, Reese-Smith JY, Lee RE. Body image and physical activity among Latina and African American women. Ethn Dis. 2011;21:281–7.

Gillen MM, Lefkowitz ES. Gender and racial/ethnic differences in body image development among college students. Body Image. 2012;9:126–30.

Brown SR, Hossain MB, Bronner Y. African American Male and Female Student Perceptions of Pulvers Body Images: Implications for Obesity, Health Care, and Prevention. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2014;25:1328–40.

Pampel FC, Krueger PM, Denney JT. Socioeconomic Disparities in Health Behaviors. Annu Rev Sociol. 2010;36:349–70.

Joh HK, Oh J, Lee HJ, Kawachi I. Gender and Socioeconomic Status in Relation to Weight Perception and Weight Control Behavior in Korean Adults. Obes Facts. 2013;6:17–27.

Delavari M, Sønderlund AL, Swinburn B, Mellor D, Renzaho A. Acculturation and obesity among migrant populations in high income countries--a systematic review. BMC Public Health. 2013;13:458. doi:10.1186/1471-2458-13-458.

Himmelgreen DA, Pérez-Escamilla R, Martinez D. The longer you stay, the bigger you get: length of time and language use in the US are associated with obesity among Puerto Rican women. Am J Phys Anthropol. 2004;125:90–6.

Gadd M, Sundquist J, Johansson S. Do immigrants have an increased prevalence of unhealthy behaviours and risk factors for coronary heart disease? Eur J Cardiovasc Prev Rehabil. 2005;12:535–41.

Hosper K, Nierkens V, Valkengoed I, Stronks K. Motivational factors mediating the association between acculturation and participation in sport among young Turkish and Moroccan women in the Netherlands. Prev Med. 2008;47:95–100.

Kaushal N. Adversities of acculturation? Prevalence of obesity among immigrants. Health Econ. 2009;18:291–303.

Calzada PJ, Anderson-Worts P. The obesity epidemic: Are minority individuals equally affected? Prim Care. 2009;36:307–17.

Tlili F, Mahjoub A, Lefevre P, Bellaj T, Romdhane HB, Eymard-Durvernay S, et al. Tunisian women’s perception of desiderable body size and chronic disease risk. Ecol Food Nutr. 2008;47:399–414.

Nicolau M, Benjelloun S, Stronks K, van Dam RM, Seidell JC, Doak CM. Influences on body weight of female Moroccan migrants in the Netherlands: a qualitative study. Health Place. 2012;18:883–91.

Swami V, Tovée MJ. Female physical attractiveness in Britain and Malaysia: a cross-cultural study. Body image. 2005;2:115–28.

Mciza Z, Goedecke JH, Steyn NP, Charlton K, Puoane T, Meltzer S, et al. Development and validation of instruments measuring body image and body weight dissatisfaction in South African mothers and their daughters. Public Health Nutr. 2005;8:509–19.

Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG, PRISMA Group. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS Med. 2009; doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000097.

Nicolaou M, Doak C, van Dam R, Hosper K, Seidell J, Stronks K. Body size preference and body weight perception among two migrant groups of non-Western origin. Pub Health Nutr. 2008;11:1332–41.

Nicolau M, Benjelloun S, Stronks K, van Dam RM, Seidell JC, Doak CM. Cultural Transition: A Qualitative Study of Body Weight in Moroccan Migrants and their Non migrant Compatriots. In: Diet and Overweight Perception: An explorative study among Turkish, Moroccan and Surinamese migrants living in the Netherland. Amsterdam: VU University Amsterdam; 2009.

Gualdi-Russo E, Rinaldo N, Khyatti M, Lakhoua C, Toselli S. Weight status, fatness and body image perception of North African immigrant women in Italy. Public Health Nutr. 2016. doi:10.1017/S1368980016000872.

Swami V, Mada R, Tovée MJ. Weight discrepancy and body appreciation of Zimbabwean women in Zimbabwe and Britain. Body Image. 2012;9:559–62.

Tovée MJ, Swami V, Furnham A, Mangalparsad R. Changing perceptions of attractiveness as observers are exposed to a different culture. Evol Hu Behav. 2006;27:443–56.

Rguibi M, Belahsen R. Overweight and obesity among urban Sahraoui women of South Morocco. Ethn Dis. 2004;14:542–7.

Rguibi M, Belahsen R. Body size preferences and sociocultural influences on attitudes towards obesity among Moroccan Sahraoui women. Body Image. 2006;3:395–400.

Jafri A, Jabari M, Dahhak M, Saile R, Derouiche A. Obesity and its related factors among women from popular neighborhoods in Casablanca, Morocco. Ethn Dis. 2013;23:369–73.

Lahmam A, Baali A, Hilali MK, Cherkaoui M, Chapuis-Lucciani N, Boetsch G. Obesity, overweight and body-weight perception in a High Atlas Moroccan population. Obes Rev. 2008;9:93–9.

El Ansari W, Labeeb S, Moseley L, Kotb S, El-Houfy A. Physical and Psychological Well-being of University Students: Survey of Eleven Faculties in Egypt. Int J Prev Med. 2013;4:293–310.

El Ansari W, Dibba E, Labeeb S, Stock C. Body image concern and its correlates among male and female undergraduate students at Assuit University in Egypt. Glob J Health Sci. 2014;6:105–17.

Jaeger B, Ruggiero GM, Edlund B, Gomez-Perretta C, Lang F, Mohammadkhani P, et al. Body dissatisfaction and its interrelations with other risk factors for bulimia nervosa in 12 countries. Psychother Psychosom. 2002;71:54–61.

McHiza ZJ, Goedecke JH, Lambert EV. Intra-familial and ethnic effects on attitudinal and perceptual body image: a cohort of South African mother-daughter dyads. BMC Public Health. 2011;11:433.

Peltzer K, Pengpid S. Body Weight and Body Image among a Sample of Female and Male South African University Students. Gender Beh. 2012;10:4509.

Puoane T, Fourie JM, Shapiro M, Rosling L, Tshaka NC, Oelefse A. ‘Big is beautiful’ – an exploration with urban black community health workers in a South African township. South Afr J Clin Nutr. 2005;18:6–15.

Faber M, Kruger HS. Dietary intake, perceptions regarding body weight, and attitudes toward weight control of normal weight, overweight, and obese Black females in a rural village in South Africa. Ethn Dis. 2005;15:238–45.

Senekal M, Steyn NP, Mashego TAB, Nel JH. Evaluation of body shape, eating disorders and weight management related parameters in black female students of rural and urban origins. S Afr J Psichol. 2001;31:45–53.

Benkeser RM, Biritwum R, Hill AG. Prevalence of overweight and obesity and perception of healthy and desirable body size in urban, Ghanaian women. Ghana Med J. 2012;46:66–75.

Siervo M, Grey P, Nyan OA, Prentice AM. A pilot study on body image, attractiveness and body size in Gambians living in an urban community. Eat Weight Disord. 2006;11:100–9.

Holdsworth M, Gartner A, Landais E, Maire B, Delpeuch F. Perceptions of healthy and desirable body size in urban Senegalese women. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. 2004;28:1561–8.

Okoro EO, Oyejola BA, Etebu EN, Sholagberu H, Kolo PM, Chijioke A, et al. Body size preference among Yoruba in three Nigerian communities. Eat Weight Disord. 2014;19:77–88.

Ettarh R, Van de Vijver S, Oti S, Kyobutungi C. Overweight, obesity, and perception of body image among slum residents in Nairobi, Kenya, 2008–2009. Prev Chronic Dis. 2013;10:E212. doi:10.5888/pcd10.130198.

Bush HM, Williams RG, Lean ME, Anderson AS. Body image and weight consciousness among South Asian, Italian and general population women in Britain. Appetite. 2001;37:207–15.

Okop KJ, Mukumbang FC, Mathole T, Levitt N, Puoane T. Perceptions of body size, obesity threat and the willingness to lose weight among black South African adults: a qualitative study. BMC Public Health. 2016;16:365. doi:10.1186/s12889-016-3028-7.

Soh NL, Touyz S, Dobbins T, Surgenor L, Clarke S, Kohn M, et al. Body image disturbance in young North European and East Asian women with and without eating disorders in Australia and in Singapore. Eur Eat Disord Rev. 2008;16:287–96.

Toselli S, Gualdi Russo E, Marzouk D, Sundquist J, Sundquist K. Psychosocial health among immigrants in Central and Southern Europe. Eur J Pub Health. 2014;24 Suppl 1:26–30.

Gradidge PJ, Norris SA, Micklesfield LK, Crowther NJ. The role of lifestyle and psycho-social factors in predicting changes in body composition in black south African women. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0132914. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0132914.

Collins ME. Body figure perception and preferences among preadolescent children. Int J Eat Dis. 1991;10:199–208.

Thompson MA, Gray JJ. Development and validation of a new body-image assessment scale. J Pers Assess. 1995;64:258–69.

Leandris CL, Lynda A, Timothy E, Leaonard J. Body size and body shape: perception of black women with diabetes. Diabetes Educator. 1999;2:382–8.

Cooper P, Taylor MJ, Cooper Z, Fairburn CG. The development and validation of the body shape questionnaire. Int J Eat Disord. 1987;6:498–506.

Stunkard AJ, Sorenson T, Schulsinger F. Use of the Danish adoption register for the study of obesity and thinness. In: Kety SS, Rowland LP, Sidman RL, Matthysse SW, editors. The genetics of neurological and psychiatric disorders. New York: Raven Press; 1983. p. 115–20.

Williamson DA, Womble LG, Zucker NL, Reas DL, White MA, Blouin DC, et al. Body image assessment for obesity (BIA O): development of a new procedure. Int J Obes Relat Netabol Disord. 2000;24:1326–32.

Becker DN, Yanek LR, Koftman CM, Bronner YC. Body image preferences among urban African Americans and White from low income communities. Ethn Dis. 1999;9:377–86.

Swami V, Salem N, Furnham A, Tovée MJ. Initial examination of the validity and reliability of the female Photographic Figure rating Scale for body image assessment. Pers Indiv Diff. 2008;44:1752–61.

Avalos L, Tylka TL, Wood-Barcalow N. The body appreciation scale: development and psychometric evaluation. Body image. 2005;2:285–97.

Cash TF. The multidimensional Body Self Relation Questionnaire Users’ Manual. 2000. http://www.body-images.com. Accessed 26 May 2016

Acknowledgement

The authors wish to acknowledge the University of Ferrara for the financial support. We would also like to thanks the Reviewers of this submission for their constructive comments that enabled this article to be improved.

Funding

This research was funded by the University of Ferrara. The funder had no role in the design, analysis or writing of this article.

Availability of data and materials

The dataset supporting the conclusions of this article is included within the article.

Authors’ contribution

EG-R conceived of the study, and participated in its design and coordination. NR carried out the literature search, data extraction and table preparation. NR and ST interpreted data and prepared the draft manuscript. EG-R performed the statistical analyses and completed the manuscript writing. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Competing interests

All authors declare (1) no support from any organization for the submitted work; (2) no financial relationships with any organizations that might have an interest in the submitted work in the previous three years; and (3) no other relationships or activities that could appear to have influenced the submitted work.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Toselli, S., Rinaldo, N. & Gualdi-Russo, E. Body image perception of African immigrants in Europe. Global Health 12, 48 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12992-016-0184-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12992-016-0184-6