Abstract

Background

The biological effects of nanoparticles depend on several characteristics such as size and shape that must be taken into account in any type of assessment. The increased use of titanium dioxide nanoparticles (TiO2NPs) for industrial applications, and specifically as a food additive, demands a deep assessment of their potential risk for humans, including their abilities to cross biological barriers.

Methods

We have investigated the interaction of three differently shaped TiO2NPs (nanospheres, nanorods and nanowires) in an in vitro model of the intestinal barrier, where the coculture of Caco-2/HT29 cells confers inherent intestinal epithelium characteristics to the model (i.e. mucus secretion, brush border, tight junctions, etc.).

Results

Adverse effects in the intestinal epithelium were detected by studying the barrier’s integrity (TEER), permeability (LY) and changes in the gene expression of selected specific markers. Using Laser Scanning Confocal Microscopy, we detected a different behaviour in the bio-adhesion and biodistribution of each of the TiO2NPs. Moreover, we were able to specifically localize each type of TiO2NPs inside the cells. Interestingly, general DNA damage, but not oxidative DNA damage effects, were detected by using the FPG version of the comet assay.

Conclusions

Results indicate different interactions and cellular responses related to differently shaped TiO2NPs, nanowires showing the most harmful effects.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

The food industry has used titanium dioxide (TiO2) since it was approved by the Food and Drug Administration (USA) in 1966 as a food additive [1]. The European Food Safety Authority (EFSA) designated the “E number” E171 to TiO2, granting it as a substance that can be used as a food additive [2]. In addition, recent evidence indicates that the use of nanosized titanium dioxide (TiO2NPs) in consumer and industrial products has exponentially increased due to their highly valuable refractive, photocatalytic and pigmenting properties [3, 4]. Even though TiO2 was classified by the International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC) as a possible human carcinogen on group 2B in 2010, the Nanotechnology Consumer Products Inventory has documented around 100 consumer products containing TiNPs and TiO2NPs to date [5]. Estimations based on the consumption of TiO2-containing food lead to the conclusion that, in the US, children and adults may be ingesting around 1–2 and 0.2–0.7 mg/kg bw/day of TiO2, respectively [6]. This highlights the relevance of ingestion as an important entryway of TiO2 and TiO2NPs in human exposures.

Nanotechnology allows the design and synthesis of TiO2NPs which present the desired physicochemical characteristics (e.g. shape, phase, and structure) in order to improve, increase, and diversify NPs’ applicability. Therefore, as the range of nanoparticle types and applications increases, the potential toxicities of these novel materials and the properties driving such toxic responses must be fully understood. To date, research with microorganisms has evidenced that the biocidal activity and cytotoxic effects of NPs are structure-, shape-, and size-dependent [7,8,9]. Furthermore, in vitro mammalian cells’ studies have reported distinct reactive oxygen species (ROS) generation patterns by different-types of TiO2 nanowires [10], differences in cytotoxicity between various crystalline-structure TiO2NPs [11], and variations in the intracellular accumulation of different crystal-phase food-grade TiO2 [12]. It has also been well documented that the crystalline phase and the primary NP diameter alters the biological impact (e.g. biodistribution, toxicokinetics, etc.) of TiO2NPs in vivo [13,14,15].

Considering oral exposure as one of the principal entry routes to the human body, the lack of conclusive studies reporting the impact of newly engineered TiO2NPs, due to the extreme difficulty of NPs detection, and how they behave across the gastrointestinal tract, is stricking. Accordingly, our study aims to evaluate the biointeractions, biodistribution, and toxicokinetics of TiO2NPs in the intestinal barrier, by assessing the biological effects of three differently shaped TiO2NPs (nanospheres, nanorods and nanowires). For this purpose, we used an in vitro model comprised of Caco-2/HT29 cocultures. After 21 days, the coculture acquires a barrier structure that faithfully mimics the human small intestine epithelium at both the morphological and functional level [16, 17]. Derived from a human colon adenocarcinoma, Caco-2 cells, as enterocyte-like cells, are able to express microvilli, tight junctions (TJ) and present paracellular, transcellular, active and transcytotic transport [18]. Differentiated Caco-2 cells also express all of the major integral membrane enzymes in charge of nutrient hydrolysis, uptake, storage and absorption [19, 20]. In parallel, HT29 cells, known as goblet cells and also derived from a human colon adenocarcinoma, are characterized by their ability to produce and secrete mucus [21].

We have shown that, when seeding at a ratio of 90% Caco-2 to 10% HT29 and culturing for 3 weeks, this in vitro model reaches good integrity levels (> 200 Ω/cm2) and is covered by a dense mucus layer, working as a barrier with two distinct scenarios, the lumen and the mucosa [22]. We previously worked in improving a more complex in vitro model, the Caco-2/HT29/Raji-B model, which also faithfully reproduces the transcytotic M cells of Payer’s Patches [22]. However, the low amount of M cells along the small intestine, as well the fact that the M-like cells expressed in the in vitro model are less than 5% [23], reduces the probability of NPs to be ingested by M-like cells. Consequently, the uptake of NPs by M-cells is difficult to detect by TEM and impossible by confocal microscopy. According to this, we chose the Caco-2/HT29 model to determine whether the mucus layer, as well as the barrier structure, could be compromised by the exposure to TiO2NPs. Moreover, we aimed to assess if the potential adverse effects are shape- and structure-dependent by comparing the most commercialized TiO2NPs, namely nanospheres (anatase-structure), nanorods (rutile-structure) and nanowires (TiO2-structure). For this purpose, we analyzed the barrier’s integrity and permeability after 24 and 48 h of TiO2NPs’ exposure, detected cellular uptake and intracellular localization by using laser confocal microscopy, and assessed the barrier functionality by gene expression. In addition, genotoxic and oxidative DNA damage were also evaluated by using the comet assay.

Methods

Nanomaterial dispersion and characterization

Three different shapes of titanium dioxide nanoparticles (TiO2NPs), pure anatase crystal-structure nanospheres of TiO2 (< 25 nm, TiO2NPs-S), pure rutile crystal-structure nanorods of TiO2 (< 100 nm of diameter, and about 250 nm of length, TiO2NPs-R), and nanowires of TiO2 (< 10 nm of diameter and 100 μm of length, TiO2NPs-W) were purchased from Sigma Chemical Co. (St. Louis, MO). To disperse them, TiO2NPs were pre-wetted in 0.5% absolute ethanol and suspended in 0.05% filtered bovine serum albumin (BSA) dissolved in autoclaved MilliQ water. TiO2NPs were sonicated in their dispersion medium for 16 min at 10% of amplitude obtaining a dispersed stock of 2.56 mg/mL, according to the Nanogenotox protocol [24]. A complete characterization of the three TiO2NPs was carried out to see their behaviour in the cell culture medium used. First, transmission electron microscopy (TEM) was used to determine the dried nanoparticle’s size and morphology on a JEOL JEM-1400 instrument (Jeol LTD, Tokyo, Japan). For this purpose, grids covered with Holey carbon film were immersed carefully in each NPs stock (2.56 mg/mL) and left to dry. Then, TEM images of random fields of view were processed with Image J software to measure and calculate the diameter of 200 NPs. Moreover, the hydrodynamic size and ζ-potential of the three TiO2NPs diluted in DMEM cell culture medium (12.5, 50, 100 and 350 μg/mL) were evaluated at 0, 24 and 48 h after sonication by dynamic light scattering (DLS) and laser Doppler velocimetry (LDV) methodologies in a Malvern ZetasizerNano-ZS zen3600 device (Malvern, UK).

Cell culture and the in vitro coculture model

The human colorectal adenocarcinoma cell line Caco-2 was kindly provided by Dr. Isabella Angelis, from Istituto Superiore di Sanità (ISS, Italia). HT29, another human cell line derived from a colorectal adenocarcinoma, was purchased from American Type Culture Collection (ATCC, Manassas VA 20108 USA). Both cell lines were maintained in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s High Glucose medium without pyruvate (DMEM w/o pyruvate, Life Technologies NY) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS), 1% non-essential amino acids (NEAA) (PAA Laboratories GmbH, Pasching, Austria) and 2.5 mg/mL plasmocin (Invivo Gen, San Diego, CA). Cells were placed in a humidified atmosphere of 5% CO2 and 95% air at 37 °C. Routinely, Caco-2 and HT29 cell lines were subcultured once a week with 1% trypsin-EDTA (PAA Laboratories GmbH, Pasching, Austria) at 7.5 × 105 cells/flask and 4 × 105 cells/flask, respectively, in 75 cm2 flask.

The in vitro coculture model was seeded in 12-well culture plates using a Polyethylene Terephthalate Transwell® (PET) insert with 1 μm pore size and an area of 1.12 cm2 (Millipore®) (Merck KGaA, Darmstadt, Germany). Briefly, 1.7 × 105 Caco-2 and HT29 cells clones were mixed and seeded on the apical side of the transwell in a ratio of 90:10, respectively. Finally, Caco-2/HT29 cocultures were left to differentiate for 21 days and the cell culture medium was changed every 3 days.

As indicated in Additional file 1: Figure S1, the Caco-2/HT29 barrier shows a structure similar to the one constituted by Caco-2 monocultures, without relevant overgrown.

Viability studies

To choose the range of sub-toxic doses to be used in our studies, an initial toxicity study was carried out. Cell viability was determined by the Beckman counter method with a ZTM Series coulter-counter (Beckman Coulter Inc., CA). Twenty-one days-old Caco-2/HT-29 cocultures were exposed for 24 and 48 h to different concentrations of TiO2NPs-S, −R and –W, ranging from 0 to 350 μg/mL. After exposure to the given NPs, barriers were washed three times with 0.5 mL of PBS (1%) and incubated 4 min at 37 °C with 0.25 mL of trypsin-EDTA 1%, to detach and individualize the cells. Finally, cells were diluted in ISOTON solution (1/100) and counted with the Beckman Cell Counter. Viability values for each concentration were calculated by averaging three independent viability experiments, each containing three replicates per sample (n = 9).

Evaluation of the barrier’s integrity in the in vitro coculture model

To monitor the formation of the differentiated barrier and its integrity, its trans-epithelial electrical resistance (TEER) was measured weekly with a Voltmeter (Millicell-ERS volt/ohm meter). TEER was measured 7, 14 and 21 days after seeding Caco-2/HT29 in PET transwells. Caco-2/HT29 cocultures with TEER values higher than 200 Ω/cm2 were used for further experiments. TEER values were also measured after TiO2NPs-S, TiO2NPs-R, and TiO2NPs-W exposure for 24 and 48 h. Briefly, after NPs exposure, the apical and basolateral chambers of the barriers were washed three times with PBS (1%) to remove the NPs as much as possible and fresh DMEM cell culture medium was placed again in the transwells. Each sample was measured three times in different parts of the insert before and after NPs exposure. TEER values for each concentration were calculated by averaging three independent experiments. TEER values were calculated according to the formula TEER = [Ω (cell inserts) - Ω (cell-free inserts)] × 1.12 cm2.

Paracellular transport through the coculture barrier

To support the integrity studies of the Caco-2/HT29 barrier, the paracellular passage of Lucifer yellow (LY) was analyzed. Briefly, after 24 and 48 h of exposure to the different TiO2NPs, barriers were washed three times with transport buffer (HBSS; Ca2+, Mg2+, + 10 mM HEPES, pH 7.4). The inserts were transferred to a new 12-well plate with 1.5 mL of HBSS in the basolateral compartment. LY diluted in HBSS was added to the apical compartment at a final concentration of 0.4 mg/mL and plates were then placed in a 37 °C incubator for 2 h. One hundred μL of each basal compartment was transferred in triplicates to a black 96-well plate. LY leakage through the barrier was measured in a prompt fluorimeter (Victor III, Perkin Elmer) plate reader using a 405–535 nm excitation-emission spectrum.

TiO2NPs localization by confocal microscopy

Laser Confocal Microscopy has demonstrated to be a useful method for localizing metallic NPs inside cells [25]. This method was used to visualize and locate the three different TiO2NPs through the cocultured barrier. For this purpose, Caco-2/HT29 barriers were exposed to 150 μg/mL of TiO2NPs-S, −R and -W for 24 and 48 h. After the exposure time, barriers were stained in situ with Hoechst 33,351 and WGA Alexa Fluor™, diluted in DMEM cell culture medium at concentrations of 1/500 and 1/100, respectively, for 15 min. Images were obtained by using a confocal laser scanning microscope Leica TC2 SP5. The three types of TiO2NPs were visualized thanks to their own reflective capability and manually masked with green colour, in contrast with the blue colour of the cells’ nucleus and the red colour or the extracellular membrane and the mucus layer. Confocal images were processed with the software Huygens Essential 4.4.0p6 (Scientific Volume Imaging, Netherlands), and Imaris 7.2.1 (Bitplane, AG).

TiO2NPs transport across the Caco-2/HT29 coculture barrier

To detect the TiO2NPs crossing through the Caco-2/HT29 barriers, laser confocal microscopy was also used. To discern if TiO2NPs’ transport was shape-, concentration- or time-dependent, coculture barriers were exposed to different concentrations (12.5, 50, 100, and 350 μg/mL) of TiO2NPs-S, −R and -W for 24 and 48 h. After the NPs’ exposure, the cell culture medium (1.5 mL) in the basolateral compartment was collected. To eliminate the inorganic material aggregates and crystallized proteins, samples were treated with proteinase K (100 μg/mL) during 30 min at 37 °C. Next, samples were centrifuged in a speed vacuum at 37 °C for 2 h to concentrate the NPs present in the medium. Finally, 10 μL of each sample was placed in slides, covered with a cover-slip, and the NPs were observed under the confocal microscopy. Several images were taken from random fields of each sample. Confocal images were processed with Huygens Essential 4.4.0p6 (Scientific Volume Imaging, Netherlands) and Imaris 7.2.1 (Bitplane, AG) softwares, where the percentage of the reflective area of each sample was calculated. Semi-quantitative values were obtained from three different experiments.

RNA extraction and gene expression by real-time qPCR

Total RNA from Caco-2/HT29 coculture barriers exposed to 0, 50 and 150 μg/mL of TiO2NPs-S, −R and –W, for 24 and 48 h, was extracted using TRIzol® Reagent (Invitrogen, USA) following the manufacturer’s instructions. RNase-free DNase I (DNA-free TM kit; Ambion, UK) was used to discard residual DNA contamination. The first-strand cDNA synthesis kit (Roche, Basel, Switzerland) was used to obtain cDNA from 100 ng of total RNA. The resulting cDNA was subjected to real-time PCR analysis on a LightCycler-480 to evaluate the relative expression of the brush border enzymes sucrase-isomaltase, alkaline phosphatase, and solute carrier family. Gene expression of tight junction components such as claudin 2, zonula occludens, and occludin. The expression of β-actin was used as the housekeeping control. The primer sequences are summarized as a table in Additional file 1: (Table S1). Each 20 μL of reaction volume contained 5 μL cDNA, 10 μL of 2× LightCycler 480 SYBR Green I Mater (Roche, Germany), 3 μL of distilled H2O and 1 μL of each primer pairs at a final concentration of 10 μM. The cycling parameters were the following: an initial step of 95 °C for 5 min, then 45 cycles of 95 °C for 10 s, 62 °C for 15 s and 72 °C for 25 s. Cycle time (Ct) values were calculated with the LightCycler 480 software package and then normalized with β-Actin Ct values.

Genotoxic and oxidative DNA damage quantification

The potential induction of genotoxic and oxidative DNA damage in Caco-2/HT29 coculture barriers was assessed by the alkaline comet assay after 24 and 48 h of exposure to TiO2NPs-S, −R, and W treatments. The concentration-range was 0, 12.5, 50, 150, and 350 μg/mL for all the TiO2-shapes. The addition of formamidopyrimidine-DNA glycosylase (FPG enzyme) was used to measure oxidatively-damaged DNA bases. The used FPG was a gift from Prof. Andrew Collins (University of Oslo). Briefly, once treated, barriers were washed twice with PBS, trypsinized (1% trypsin), and centrifuged at 1000 rpm for 8 min. The pellet was then resuspended in PBS to a concentration of 700 cells/μL and placed in ice at 4 °C, to avoid DNA repair. 25 μL of cells’ suspension was mixed with 0.75% of LMP agarose at 37 °C and dropped (7 μL/drop and 3 drops/sample) on Gelbond (GB) films. Cells on GB were lysed in lysis buffer at 4 °C and pH 10 overnight. The next morning, GB were washed twice (1 × 5 min, and 1 × 50 min) in enzyme buffer at 4 °C and pH 8.0, followed by a 30 min incubation with the enzyme buffer at 37 °C. One GB was incubated with enzyme buffer and FPG enzyme (1/10.000), and the other in enzyme buffer without FPG. GB were incubated with electrophoresis buffer (alkaline buffer) for 35 min followed by the electrophoresis step for 20 min at 20 V and 300 mA at 4 °C. Finally, GB were rinsed twice in cold PBS for 5 min, in distilled water for 1 min, fixed in absolute ethanol for at least 2 h, air-dried overnight at room temperature, and stained with SYBR Gold for 20 min. Each GB film was cut into two similar-sized parts to fit in an acrylic slide (52.5 × 75 × 3 mm). A coverslip of 52.5 × 75 mm was placed on top of the drops, effectively sealing the samples. GB were observed using an epifluorescent Olympus BX50 and damage was quantified measuring the percentage of DNA in tail by using the Komet 5.5 Image analysis software. One hundred randomly-selected comet images were analyzed per sample. 30 min treatments of 5 mM of potassium bromate (KBrO3) and 2.5 mM of methylmethanesulfonate (MMS) were used as positive control of oxidative and genotoxic damage, respectively.

Statistical analysis

All measurements were made in triplicates, at least for 2 separate experiments. Results are expressed as mean ± standard error. One-way ANOVA with Tukey’s post-test, unpaired and paired Student’s t-test or two-way ANOVA were used to compare differences between means. Data were analyzed with GraphPad Prism version 5.00 for Windows (GraphPad Software, San Diego California USA, http://www.graphpad.com). Differences between means were considered significant at P < 0.05.

Results

Nanoparticles characterization

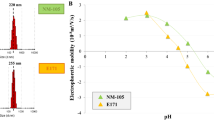

Our TEM images demonstrate that the sizes of TiO2NPs-S, TiO2NPs-R and TiO2NPs-W ranged from 70 to 80, 40–70 and 8–14 nm, respectively (Fig. 1; A.1, A.2 and A.3), which are similar to the sizes given by the manufacturer. In spite of the dry form sizes of the NPs, the hydrodynamic diameter measured with the DLS technique gives higher values for the three TiO2NPs, reaching mean diameters above 200 nm in most cases (Fig. 1e). These differences between primary and hydrodynamic size suggest that TiO2NPs aggregate in the cell culture medium. No significant changes were seen in size distribution for -S or -R forms in cell culture medium (DMEM) over the incubation time. However, a slight size reduction in -W was observed after 48 h. As differences between TiO2NPs structures and shapes were detected, we also aimed to study the hydrodynamic size distribution according to the used concentrations (Additional file 1: Figure S2). Interestingly, different behaviours among TiO2NPs were observed: -S presented a tendency to aggregate that was clearly concentration-dependent, as higher concentrations correlated with bigger NPs. On the contrary, no concentration nor time-dependent correlations were observed for TiO2NPs-R. Regarding -W size distribution, only the lowest concentration (12.5 μg/mL) decreased its aggregation over time, while the higher concentrations presented similar sizes distributions. In spite of the inaccuracy of the size data for nano-filaments measurements, DLS gives important information about the agglomeration state of our dispersion. As nanowires agglomerate, then move slower in the dispersion medium and the average diameter value is bigger [26]. PDI values were higher in -S (0.472, 0.581 and 0.544) and in -W (0.596, 0.565 and 0.629) than in -R (0.202, 0.211 and 0.216), suggesting that -R have greater monodisperse size distribution than the others.

TiO2NPs characterization. TEM images of TiO2NPs-S (A.1), TiO2NPs-R (B.1), and TiO2NPs-W (C.1) in their dry form. Size distribution of TiO2NPs-S (A.2), TiO2NPs-R (B.2), and TiO2NPs-W (C.2) of 200 randomly-selected nanoparticles. (E) Dynamic light scattering (DLS) and laser Doppler velocimetry (LDV) measurements of 50 μg/mL TiO2NPs over the exposure time (0, 24, and 48 h). Data are represented as mean ± SD

No changes in PDI values were detected over time for any of the evaluated TiO2NPs. The stability of the colloidal system was measured by LDV, indicating the TiO2NPs surface charge when dispersed in cell culture medium. Our results evince little stability in all TiO2NPs solutions since the ζ-potential values barely reach the ±30 mV (Fig. 1e).

Cytotoxic effects of the Caco-2/HT29 coculture barrier exposed to TiO2NPs

To determine the cytotoxic effects of TiO2NPs-S, −R and –W, and to know whether their shape and titanium-based structure play a role in cell viability, we exposed the 21-days cocultures to concentrations ranging from 12.5 to 350 μg/mL for 24 and 48 h. In Additional file 1: Table S3, we indicated the relationship between μg/mL and μg/cm2. Since ingested TiO2NPs have low absorption in rats [27], and human ingestion has shown to be daily [6], we evaluated the effects at two different times (24 and 48 h). As Fig. 2 indicates, noncytotoxic damage was detected after 24 h of -S, −R, and -W exposures, as all the registered viability values were above the 80%. Nevertheless, when cell viability was checked after 48 h of exposure, a drastic decrease in cell viability was observed for the three TiO2NPs-shapes, although these effects were not concentration-dependent. Interestingly, the concentration of 150 μg/mL seems to be the most toxic since it caused the highest mortality in all the TiO2NPs tested at 48 h. In spite of the observed toxicities, we can conclude that shape can be associated with adverse effects as cytotoxicity.

Evaluation of the barrier’s integrity after TiO2NPs’ exposure

The main function of an epithelial barrier is to confer stability, protection, and the desired permeability to each tissue and/or organ. In these functions, TJ play an important role forming belt-like and apical-most adhesive junctional complexes around mammalian cells [28]. We can evaluate the functional integrity of the barrier measuring the TEER before and after the exposure to TiO2NPs. No significant reduction was seen in the integrity of the barrier when exposed to TiO2NPs-S for 24 h (Fig. 3a). However, significant differences (P < 0.05) between TEER values were observed by exposing the barriers to 150 μg/mL of both TiO2NPs-W (Fig. 3c), and TiO2NPs-R (Fig. 3e). Moreover, rod-shaped NPs were also able to decrease the membrane’s stability at 350 μg/mL (P < 0.001). When the exposure time was extended to 48 h, statistically significant adverse effects on the barrier’s integrity were detected for all TiO2NPs shapes at different NPs concentrations (Fig. 3b, d and f), although no concentration-dependent effect was observed.

A reduction in the barrier’s integrity and stability may cause increased permeability to a wide range of endogenous and exogenous particles and/or substances. Thus, we initially focused our integrity studies on analyzing the possible variations of paracellular transport, measuring the pass of LY across the barrier after TiO2NPs exposure. The results obtained agree with the TEER variations observed previously. As we can see in Fig. 4, no increases in the ratio of basolateral LY were observed when the barrier was exposed for 24 h to TiO2NPs-S. However, the highest concentrations of TiO2NPs-R, and –W significantly incremented LY’s passage (Fig. 4a). Also, 48 h exposures to all the three TiO2NPs induced significant increases in basolateral LY concentrations when compared to the control. Summarizing, our results show that all TiO2NPs disrupt the cell membrane’s integrity and permeability by increasing its paracellular transport. Interestingly, exposure to TiO2NPs-W was the most harmful, modifying stability parameters in most of the experimental conditions.

Percentage of LY found in the basolateral chamber of the transwell. The paracellular transport of LY was measured after treating the Caco-2/HT29 co-culture barriers with TiO2NPs-S, TiO2NPs-R, and TiO2NPs-W for 24 (a) or 48 h (b). Results represented as mean ± SEM. Bars that do not share any letter are significantly different according to the one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s post-test (P < 0.05)

Assessing detrimental effects of TiO2NPs exposure by gene expression

To support our integrity and permeability results, and to evaluate the barrier status, changes in gene expression of several markers associated with different intestinal barrier functions were analysed. To this aim, the Caco-2/HT29 coculture was exposed to 50 and 150 μg/mL of TiO2NPs-S, −R, and –W, for 24 and 48 h. We analyzed changes in the expression of genes related to nutrient uptake and digestion, as well as in genes responsible for sealing intercellular spaces, thus conferring the barrier function. This set of genes, their encoded proteins and their functions are summarized in Table 1.

Interestingly, we observed a significant and consistent down-regulation of ALPI in all exposure conditions and for all the TiO2NPs shapes tested (Fig. 5a). Contrarily, significant increases in SI expression were detected after 24 and 48 h of TiO2NPs-R, and -W exposure, while -S exposure was able to upregulate this gene’s expression only after 48 h (Fig. 5c). SLC15A1 gene expression also increased significantly, but only when the barrier was exposed to 50 μg/mL TiO2NPs-R for 48 h (Fig. 5e). Summarizing, the expression of different enzymatic functions could be affected distinctly depending on the TiO2NPs structure, dose and time, either by enhancement or by reduction.

Regarding the gene expression changes of the main integral membrane proteins located at the TJ (OCLN, CLDN2 and ZO-1), results were more homogeneous. Generally, the exposure to TiO2NPs-S did not significantly modify the gene expression of ZO1 at any time nor concentration. Conversely, ZO1 was significantly downregulated when the barrier was exposed to 50 and 150 μg/mL of TiO2NPs-R for 24 h, while 150 μg/mL TiO2NPs-W exposure upregulated ZO1 expression after 24 h (Fig. 5b). OCLN was upregulated after 24 h of exposure to TiO2NPs-S and also to TiO2NPs-R, and –W, both after 24 and 48 h (Fig. 5d). Finally, CLDN2 was significantly upregulated in all experimental conditions after exposing the barrier to TiO2NPs-S. However, only exposure to TiO2NPs-R and -W for 48 h upregulated CLDN2 expression (Fig. 5f). Taken together, these data suggest that the NPs’ shape could interact distinctly with the junctional complex modulating different responses.

Caco-2/HT29 barrier uptake of TiO2NPs

Confocal microscopy was used to qualitatively localize TiO2NPs in our barrier model, specifically in each of its components (i.e. mucus shed, cell cytoplasm, cell nuclei, apical and basal areas, etc.). As metallic NPs have the capability to reflect polarized light, their detection results easier by confocal microscope than by electron microscopy. Furthermore, we aimed to study whether the NPs’ structure and shape could influence uptake and/or translocation, and to check potential biointeractions and biodynamics over the exposure time. Briefly, the status of Caco-2/HT29 coculture barriers was analyzed after 24 h and 48 h exposures to 150 μg/mL of TiO2NPs-S, TiO2NPs-R, and TiO2NPs-W. Figure 6 shows confocal images corresponding to transversal cuts of the barrier, where it is possible to distinguish the cell nucleus in blue, the TiO2NPs in green, and the mucus secretions and cell membranes in red. As observed, after 24 h of exposure most of the TiO2NPs-S and TiO2NPs-R remained sedimented and/or attached to the apical side of the barrier, where the microvilli and mucus shed form an extracellular environment suitable for the NPs immobilization (Fig. 6a and c). Although not in a quantitative manner, we can assume that the trapped NPs in the apical side are more aggregated/agglomerated than those located deeper in the barrier (white circles). Interestingly, the amount of TiO2NPs-S detected in the apical part of the barrier was clearly reduced after 48 h of NPs exposure, while the amount of TiO2NPs-R was similar at both time points. As images E and F from Fig. 6 show, after 24 and 48 h of exposures to 150 μg/mL of TiO2NPs-W the barrier looked more damaged and compromised at a structural level when compared to the other TiO2NPs exposures. Also, the amount of internalized TiO2NPs-W, at both time points, was markedly lower.

Confocal microscope z-scans of Caco-2/HT29 co-culture barriers after TiO2NPs-S (a and b), TiO2NPs-R (c and d), and TiO2NPs-W (e and f) exposures lasting for 24 h (a, c and e), or 48 h (b, d and f). Cell nuclei (blue) were stained with Hoechst and cell membrane and mucus (red) with WGA. NPs were visualized by reflection and marked with a green mask. Images were processed with the Imaris 7.2.1 software

Using the confocal technique, we were able to elucidate the exact location of TiO2NPs in the cocultured cells, although the identification of each cell type was not possible. As white arrows indicate (Fig. 7), TiO2NPs-S (A), −R (C), and -W (E) were detected in the cell cytoplasm after 24 h of exposure, and in most cases, they reached the cell nucleus. When evaluating the three-dimensional images from samples exposed to the three different TiO2NPs shapes for 48 h, lower amounts of TiO2NPs-S were still immobilized in the apical part of the membrane (white circle), and fewer NPs were detected inside the cells (white arrows) (Fig. 7b). Similar results were obtained when the barriers were exposed to TiO2NPs-R (Fig. 7d), and TiO2NPs-W (Additional file 1: Figure S3) for 48 h. As previously observed, fewer cell junctions and cohesion were found when checking in detail the cocultures exposed to TiO2NPs-W for both 24 (Fig. 7e) and 48 h (Fig. 7f). Moreover, TiO2NPs-W were clearly detected at different levels of the barrier width (white arrow).

Three-dimensional confocal images of the Caco-2/HT29 co-culture barriers z-scans from Fig. 6. Images were taken after exposures of 24 or 48 h to TiO2NPs-S (a and b), TiO2NPs-R (c and d), and TiO2NPs-W (e and f). Cell nuclei (blue) were stained with Hoechst, and mucus (red) was stained with WGA. NPs were visualized by reflection and marked with a green mask. White arrows indicate NPs in the cell cytoplasm and NPs-nucleus interactions. Images were processed with the Imaris 7.2.1 software

Nanoparticles translocation through the Caco-2/HT29 barrier

As the capability of the three TiO2NPs to penetrate the Caco-2/HT29 coculture barrier was detected, we aimed to find and quantify any amount of translocated TiO2NPs by analyzing the basolateral medium of the barrier model. Our previous experience working with Caco-2 monolayers demonstrates that confocal microscopy is one of the best techniques to localize metallic NPs in the basolateral media. Thereby, after 24 or 48 h of TiO2NPs-S, −R, and -W exposure, we collected the entire basolateral medium (1.5 mL), treated it with proteinase K, and concentrated the sample by evaporating the cell medium using a speed vacuum. After that, each sample was analyzed under the confocal microscope, where several pictures were taken in random fields of a slide (Additional file 1: Figure S4). Semi-quantitative data was obtained by measuring the percentage of the area reflected by the different TiO2NPs. As Fig. 8 shows, the transport of TiO2NPs-S through the barrier was not concentration-dependent. However, the amount of NPs found in the basolateral chamber 48 h after exposure (~ 5% of the area) was almost two times higher than at 24 h (~ 2% of the area). On the other hand, the TiO2NPs-R transport was clearly concentration- and time-dependent. Finally, although TiO2NP-W in the basal growth medium also increased with the exposure time, nanowires behave differently than the rods, as its transport decreased when the exposure concentration increased.

Percentage of the TiO2NPs-reflective area of the basolateral chamber of the transwell. The transport of TiO2NPs-S (a), TiO2NPs-R (b), and TiO2NPs-W (c) across the Caco-2/HT29 co-culture barrier was calculated using Laser Confocal microscopy and by measuring the reflected light of randomly selected slide fields. Data are represented as mean ± SEM

Genotoxic and oxidative damage. The comet assay

The comet assay was used to analyze the consequences of the TiO2NPs-cell nucleus interaction previously observed by confocal microscopy. Moreover, we also aimed to elucidate if this response was concentration and/or time-dependent. As depicted in Figs. 9, 24 h of TiO2NPs-S, TiO2NPs-R, and TiO2NPs-W exposure significantly increased the general genotoxic damage in our barrier model (Fig. 9a). Nevertheless, after 48 h of TiO2NPs exposure, only those barriers exposed to TiO2NPs-R sustained a non-concentration dependent genotoxic damage (Fig. 9b). Methyl methanesulphonate (MMS), a well-known genotoxic compound used as positive control, clearly induced general genotoxic damage to the cocultured cells (Fig. 8a and b).

DNA damage studies using the Comet assay complemented with the FPG enzyme. Genotoxic damage observed after 24 (a) or 48 (b) h of exposure to TiO2NPs (-S, −R and -W). Mean oxidative damage observed after 24 (c), and 48 (d) h of exposure to TiO2NPs (-S, −R and -W). (*) denotes significant differences according to the one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s post-test (*P < 0.05, **P < 0.01***P < 0.001). Results are represented as mean ± SEM

The potential ability to induce oxidative damage was also detected performing the alkaline version of the comet assay, where oxidatively-damaged DNA bases (e.g. 8-oxodG and FAPydG) were detected using the formamidopyrimidine glycosylase enzyme (FPG), thereby increasing the number of DNA breaks. The difference in the percentage of DNA in tail between cells treated with FPG and those left untreated gave us a measure of the amount of oxidative DNA damage [29, 30]. In this case, no significant increase in oxidative DNA damage was detected after 24 h of TiO2NPs-S, −R and -W exposure, or after exposures lasting for 48 h. As a positive control, we used the well-known oxidant agent, potassium bromate (KBrO3), which increased a 60% the oxidative DNA damage at the Caco-2/HT29 barrier.

Discussion

The International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC) performed the last reevaluation on the potential cancer risk of TiO2 in 2010 [31]. According to the collected information, TiO2 was classified as a potential human carcinogen in group 2B, because there was enough evidence that inhalation of nano-TiO2 may cause lung cancer. Although IARC considered the risk associated with oral exposure, inconclusive outcomes were obtained due to the lack of standardized procedures for nano-TiO2 risk assessment, as pointed out by Jacobs et al. [32]. Under this framework, we aimed to investigate the potential hazard of three different shapes and crystal structures of TiO2NPs using an in vitro model of intestinal barrier constituted by Caco-2 and HT29 cells cocultures.

A preliminary characterization of the selected TiO2NPs showed larger hydrodynamic diameter values than their primary sizes. This would agree with other studies showing the general tendency of NPs, and of TiO2NPs in particular, to form agglomerates in cell culture media [33, 34]. Interestingly, our results showed that crystallinity and morphology are not influential factors in determining the stability of TiO2NPs suspensions, which agrees with previously reported data [35]. Although most of the studies barely take into account the potential role of incubation time when characterizing NPs, we strongly believe that this should be a prerequisite to understanding the effects of the exposure time and their multiple potential biological effects. Accordingly, we took this parameter into consideration but we did not detect relevant variations in the hydrodynamic size for TiO2NPs-S or TiO2NPs-R over the incubation time (0, 24, and 48 h). Nevertheless, a slight reduction in the hydrodynamic size for TiO2NPs-W was observed, which would indicate the lack of time-dependent aggregation. The agglomeration status of NPs can influence the potential toxicity by changing their uptake and/or the way they interact with cells. In fact, changes in this parameter are considered as one of the main reasons for the contrasting data reported in different studies [33, 36].

Even though exposure to TiO2NPs occurs chronically in humans, it should be pointed out that cells from the gastrointestinal tract are submitted to a high turnover. Contrarily to this chronic in vivo exposures, most of the in vitro studies testing potential biological effects are performed evaluating effects over a short exposure time (e.g. after 4, 6 or 24 h). These short exposure times do not reflect the observed in vivo NPs effects [37]. To increase the fidelity of in vitro models, elongating the exposure time and minimizing the exposure concentration could be a useful approach; however, the increase of the exposure times (6, 24 and 48 h) did not cause variations in the observed effects on Caco-2 monolayers [38]. Going one step further, we have been able to detect a significant reduction in cell viability after 48 h for all TiO2NPs-shaped exposures using our Caco-2/HT29 coculture model, which points out the relevance of exposure time. Nonetheless, our results are in contradiction with those observed in Caco-2/HT29-MTX cocultures, where no cytotoxic effects were observed after similar exposure conditions [38, 39]. As previously stated, the agglomeration status after 48 h of TiO2NPs suspended in serum-containing cell culture medium was smaller for TiO2NPs-R and TiO2NPs-W and similar for TiO2NPs-S in our case. This could be a potential factor explaining the increased cytotoxicity over the exposure times. In addition, our model, using the HT29 clone, and the proportion 90% of Caco-2 and 10% of HT29, has demonstrated a proper mucus secretion that spreads all over the surface of the barrier, forming a thick mucus layer and conferring a good protection and integrity [22]. Since Dorier et al. [38] and Brun et al. [39] used a different HT29 cell clone, and their cocultures were composed by 70% of Caco-2 and 30% HT29-MTX, these factors would explain the observed differences and, at the same time, would reinforce the usefulness of our model.

To characterize the effects of the interaction of the three TiO2NPs shapes with the barrier, we assessed its functionality and permeability by TEER and LY paracellular crossing. Although TiO2NPs-S did not disrupt the integrity of our model after 24 h exposures, small but significant effects were observed for TiO2NPs-R and –W at this time point, pointing out the relevance of the NPs’ shape when analyzing its effects. The extension of the exposure time enhanced the damaging effects observed at 24 h, as the three different shapes of TiO2NPs affect the barrier’s integrity after exposures lasting for 48 h. Interestingly, the observed adverse effects on the barrier’s integrity depend on the shape of the TiO2NPs used as well: TiO2NPs-W causes the most adverse effects, while TiO2NPs-S is the least hazardous. Moreover, the observed upregulation in genes encoding different TJ components (ZO-1, OCLN, and CLDN2) indicates the presence of active repair by inducing de novo expression of junctional proteins [39], confirming the cell junctions’ and the barrier’s integrity impairment.

After NPs ingestion, they can interact with a number of biologically significant tissues and structures, as the enterocytes’ brush border (microvilli). In fact, it has already been observed that the adsorption of NPs results in the disruption of the brush border’s structure [40, 41], where approximately 42% of microvilli were lost after the exposure to food-grade TiO2 [42]. In our case, we have found that exposures to different TiO2NPs’ shapes also altered significantly the Caco-2/HT29 brush border membrane and enzymatic function, as the expression of ALPI was readily and radically downregulated after exposure to all of the TiO2NPs. It must be noted that a recent study analyzing ALPI’s enzymatic activity in Caco-2/HT29-MTX cocultures observed an increased activity after acute and chronic TiO2NPs exposures [43]. These discrepancies between post-transcriptional and post-translational regulations lead us to hypothesize that an enzyme over-activation of ALPI in response to TiO2NPs might trigger the block of its gene transcription to mRNA. In addition, the SI gene expression was upregulated after most of the exposure conditions analyzed, suggesting an active response to carbohydrates starvation caused by the TiO2NPs exposure. Finally, the upregulation of SLC15A1 gene expression was detected after TiO2NPs-R exposure, but not after TiO2NPs-S and TiO2NPs-W ones. This would agree with what was observed in Caco-2 monolayers exposed to rutile TiO2NPs for 48 h [12]. Overall, TiO2NPs exposure affects the barrier’s integrity, but each brush border enzyme may follow different strategies to stabilize its correct function, independently of the concentration exposure and NP shape.

The disruption of the barrier integrity can potentially affect cellular uptake and translocation throughout the barrier of the TiO2NPs, making the evaluation of these parameters necessary to evaluate the risk of exposure. A wide number of mammalian cell type models internalize TiO2NPs, including differentiated Caco-2 cells [41, 44]. Interestingly, the capability of differentiated Caco-2 cells to internalize TiO2NPs depends on their structure, as more rutil- than anatase-structured TiO2NPs were observed in differentiated Caco-2 [12, 39]. When the Caco-2/HT29 cocultures are established, technical difficulties to follow and locate the NPs position inside individualized Caco-2 or HT29 cells appear. To elucidate the TiO2NPs distribution in our in vitro model of the intestinal barrier, we used laser scanning confocal microscopy. With this methodological approach, we detected that (i) numerous TiO2NPs-S and -R agglomerates remain deposited and entrapped in the apical part of the barrier, where the mucus shed and microvilli are located; while the smaller agglomerates could penetrate the barrier deeper; (ii) TiO2NPs-R were more confined between mucus and microvilli than TiO2NPs-S and TiO2NPs-W; (iii) differences in bio-persistence between NPs shapes were clearly seen through the time exposure; (iv) TiO2NPs-W apparently impaired the barrier structure readily after 24 h of NPs treatment; (v) the three shapes of TiO2NPs were able to cross the mucus shed, enter into the cell’s cytoplasm and, finally, go close the cell nucleus; (vi) more TiO2NPs-R/cell nucleus interaction events were seen when compared to TiO2NPs-S and -W, at the same concentration; and (vii) TiO2NPs-W presented more paracellular transport through the barrier than the other shapes. Taken together, we demonstrate the usefulness of our methodological approach, as well as the differential uptake depending on the NPs’ shape. In fact, Chen et al. [45] already demonstrated that spherical TiO2NPs and nanorods could be more readily internalized in HeLa cells than filamentous ones. In spite of the obtained images, a limitation of the technique is that it does not differentiate the NPs internalization rate on each cell type used in the model (absorptive or goblet cells). However, both cell types in monocultures have demonstrated to internalize TiO2NPs [44, 46].

TiO2NPs are absorbed in the gastrointestinal tract, delivered to the bloodstream and distributed to different organs [15]. According to this, translocation through our barrier model must be demonstrated. Using confocal microscopy, we detected the presence of the three different shapes of TiO2NPs in the basolateral chamber, indicating the ability of TiO2NPs to pass through the in vitro intestinal barrier, independently of their shape. A relationship between TiO2NPs’ shape-translocation ability was observed with an increasing concentration-dependent translocation for TiO2NPs-R and the opposite for TiO2NPs-W. Moreover, constant translocation was seen for all TiO2NPs shapes, as the amount of NPs was higher at 48 than at 24 h. This leads us to think that the physicochemical characteristics of each TiO2NPs shape can influence their translocation rate. Results from Brun et al. [39] only found TiO2NPs translocation in a Caco-2/Raji-B model, but not in the Caco-2/HT29-MTX one, suggesting that TiO2NPs pass only through transcellular transport through M cells. However, we provided enough evidence that TiO2NPs-S, −R and -W can alter the barrier’s integrity and paracellular transport permeability, to translocate to the serosa of the intestinal tract. Moreover, we also observed a clear TiO2NPs-S and -R internalization, probably by both cell types, also indicating a putative transcellular transport.

Among the potentially adverse health effects of TiO2NPs internalization, many authors point out genotoxicity on target cells. However, previous in vitro and in vivo studies evaluating the genotoxicity of TiO2NPs present conflicting results [47]. The review of Chen et al. [45] stated that in vitro models generated more positive results than the in vivo ones, and assays detecting DNA and chromosome damage produced more positive outcomes than those measuring gene mutation. Strong evidence indicates that the genotoxicity of TiO2NPs is specifically mediated through the generation of oxidative stress [48]. ROS production might lead to the formation of oxidative DNA damage, primarily 8-oxo-dG adducts, which are considered promutagenic lesions [49]. Hence, the accumulation of these lesions could trigger the cell transformation upon chronic exposures [24].

The morphological status of Caco-2 cells can play an important role in genetic damage prevention, as most studies on undifferentiated cells respond to NPs exposure [11, 50, 51], opposite to what is observed in differentiated cells [12]. This was also indirectly measured by the induction of ROS, observed only in undifferentiated Caco-2 cells [44]. This different behaviour can be explained by the higher uptake of NPs observed in undifferentiated cells, when compared to differentiated cells structured as a monolayer, something that has been demonstrated for nanoceria [52]. In our model, none of the tested TiO2NPs shapes was able to induce oxidative DNA damage at any of the tested conditions. This would agree with recently reported data in a Caco-2/HT29-MTX model under acute or chronic exposures [38]. In spite of this, we were able to detect DNA strand breaks in TiO2NPs-exposed cells. These DNA breaks could result from the direct interaction of TiO2NPs with the nucleus, as detected in our confocal images. General DNA strand breaks were detected readily after 24 h in all TiO2NPs shapes exposures. Interestingly, the genotoxic damage persisted after 48 h of TiO2-R treatment, which were the more biopersistent TiO2NPs in our intestinal barrier model. As previously mentioned, both Caco-2 and HT29 cell types may present different cell uptake rates and, consequently, different DNA damage levels. Unfortunately, we were not able to distinguish the most damaged cell type in the pool of Caco-2/HT29 cells, as the techniques used do not permit the identification of a particular cell type. The separation of both populations after the barrier’s exposure to NPs, by cell sorting methodologies, could bring light to this issue.

Conclusions

As a summary, the results of this study demonstrate that the three different shapes of TiO2NPs behave distinctly when dispersed in DMEM cell culture medium. This can affect their agglomeration status and, as a consequence, their toxic effects. The observed toxic effects aggravated by increasing the time of exposure, as a slight but significant reduction in cell viability was seen after 48 h. We have shown that all three NPs were able to cross the mucus layer, the cell barrier model, and reach the basolateral compartment. Both TiO2 nanospheres and nanorods were uptaken easier and faster than nanowires, using transcellular transport to cross the barrier model. However, more adverse effects were seen after exposing the barrier to TiO2NPs-W, as the nanowires clearly impaired and compromised the Caco-2/HT29 barrier’s integrity and permeability, using the paracellular transport to cross the barrier. Interactions between the three NPs and the cell nuclei were seen by confocal microscopy, and the consequences were reflected in a significant increase in DNA damage levels. However, we cannot discern if each cell type, Caco-2 and HT29, is equally sensitive to the adverse effects of the selected NPs. Although we have only focused on shape and exposure variables we are aware that other factors such as crystallinity can also to have some influence on the behavior of TiO2NPs. In fact, the anatase form induced strongly dendritic cells maturation and showed a stronger adjuvant activity in an in vivo allergy model than rutile form [53]. Further improvements in the model would be useful to solve some unanswered questions regarding the different sensitivities of the cell components of this model, as well as the effects of long-term exposures. In fact, in Caco-2 monolayers, significant differences between exposures lasting 24 or 72 h have been reported [54]. Nevertheless, in the Caco-2/HT29 model 72 h after barrier differentiation (21 days) the barrier starts to detach and destabilize. This is a challenge that must be overcome.

References

Code of Federal Regulations (CFR). Title 21, updated April 1, 2016. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/scripts/cdrh/cfdocs/cfcfr/CFRSearch.cfm.

European Food Safety Authority (EFSA). Re-evaluation of titanium dioxide (E171) as a food additive. (2016). http://www.efsa.europa.eu/en/efsajournal/pub/4545.

Chen X, Mao SS. Titanium dioxide nanomaterials: synthesis, properties, modifications, and applications. Chem Rev. 2007;107:2891–959.

Horie M, Sugino S, Kato H, Tabei Y, Nakamura A, Yoshida Y. Does photocatalytic activity of TiO2 nanoparticles correspond to photo-cytotoxicity? Cellular uptake of TiO2 nanoparticles is important in their photo-cytotoxicity. Toxicol Mech Methods. 2016;26:284–94.

Vance M, Kuiken T, Vejerano E, McGinnis S, Hochella M Jr, Rejeski D, Hull M. Nanotechnology in the real world: redeveloping the nanomaterial consumer products inventory. Beilstein J Nanotechnol. 2015;6:1769–80.

Weir A, Westerhoff P, Fabricius L, Hristovski K, von Goetz N. Titanium dioxide nanoparticles in food and personal care products. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2012;46:2242–50.

Pal S, Tak Y, Song J. Does the antibacterial activity of silver nanoparticles depend on the shape of the nanoparticle? A study of the gram-negative bacterium Escherichia coli. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2007;73:1712–20.

Ercan B, Taylor E, Alpaslan E, Webster T. Diameter of titanium nanotubes influences anti-bacterial efficacy. Nanotechnology. 2011;22:5102–12.

Aminedi R, Wadhwa G, Das N, Pal B. Shape-dependent bactericidal activity of TiO2 for the killing of gram-negative bacteria Agrobacterium tumefaciens under UV torch irradiation. Environ Sci Pollut Res. 2013;20:6521–30.

Park E, Shim H, Lee G, Kim J, Kim D. Comparison of toxicity between the different-type TiO2 nanowires in vivo and in vitro. Arch Toxicol. 2013;87:1219–30.

Gerloff K, Fenoglio I, Carella E, Kolling J, Albrecht C, Boots AW, Förster I, Schins RP. Distinctive toxicity of TiO2 rutile/anatase mixed phase nanoparticles on Caco-2 cells. Chem Res Toxicol. 2012;25:646–55.

Dorier M, Brun E, Veronesi G, Barreau F, Pernet-Gallay K, Desvergne C, Rabilloud T, Carapito C, Herlin-Boime N, Carrière M. Impact of anatase and rutile titanium dioxide nanoparticles on uptake carriers and efflux pumps in Caco-2 gut epithelial cells. Nanoscale. 2015;7:7352–60.

Grassian V, O’Shaughnessy P, Adamcakova-Dodd A, Pettibone J, Thorne P. Inhalation exposure study of titanium dioxide nanoparticles with a primary particle size of 2 to 5 nm. Environ Health Perspect. 2007;115:397–402.

Gui S, Zhang Z, Zheng L, Cui Y, Liu X, Li N, Sang X, Sun Q, Gao G, Cheng Z, Cheng J, Wang L, Tang M, Hong F. Molecular mechanism of kidney injury of mice caused by exposure to titanium dioxide nanoparticles. J Hazard Mater. 2011;195:365–70.

Zhao X, Ze Y, Gao G, Sang X, Li B, Gui S, Sheng L, Sun Q, Cheng J, Cheng Z, Hu R, Wang L, Hong F. Nanosized TiO2-induced reproductive system dysfunction and its mechanism in female mice. PLoS One. 2013;8:e59378.

Antunes F, Andrade F, Araújo F, Ferreira D, Sarmento B. Establishment of a triple coculture in vitro cell models to study intestinal absorption of peptide drugs. Eur J Pharm Biopharm. 2013;83:427–35.

Lozoya-Agullo I, Araújo F, González-Álvarez I, Merino-Sanjuán M, González-Álvarez M, Bermejo M, Sarmento B. Usefulness of Caco-2/HT29-MTX and Caco-2/HT29-MTX/Raji B coculture models to predict intestinal and colonic permeability compared to Caco-2 monoculture. Mol Pharm. 2017;14:1264–70.

Artursson P, Palm K, Luthman K. Caco-2 monolayers in experimental and theoretical predictions of drug transport. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2001;46:27–43.

Levy E, Mehran M, Seiman E. Caco-2 cells as a model for intestinal lipoprotein synthesis and secretion. FASEB J. 1995;9:626–35.

Shen H, Qin H, Guo J. Cooperation and metallothionein and zinc transporters for regulating zinc homeostasis in human intestinal Caco-2 cells. Nutr Res. 2008;28:406–13.

Lesuffleur T, Barbat A, Dussaulx E, Zweibaum A. Growth adaptation to methotrexate of HT-29 human colon carcinoma cells is associated with their ability to differentiate into columnar absorptive and mucus-secreting cells. Cancer Res. 1990;50:6334–43.

García-Rodríguez A, Vila L, Cortés C, Hernández A, Marcos R. Exploring the usefulness of the complex in vitro intestinal epithelial model Caco-2/HT29/Raji-B in nanotoxicology. Food Chem Toxicol. 2018;113:162–70.

Verhoeckx K, Cotter P, López-Expósito I, Kleiveland C, Lea T, Mackie A, Requena T, Swiatecka D, Wichers H. The impact of food bioactives on health: in vitro and ex vivo models. Heidelberg: Springer Int Publ; 2015.

Nanogenotox. 2011. http://www.nanogenotox.eu/files/PDF/Deliverables/nanogenotox%20%20%20deliverable%25%20203_wp4%20dispersion%20protocol.pdf.

Vila L, Marcos R, Hernández A. Long-term effects of silver nanoparticles in caco-2 cells. Nanotoxicology. 2017;11:771–80.

Bihari P, Vippola M, Schultes S, Praetner M, Khandoga AG, Reichel CA, Coester C, Tuomi T, Rehberg M, Krombach F. Optimized dispersion of nanoparticles for biological in vitro and in vivo studies. Part Fibre Toxicol. 2008;5:14.

Cho WS, Kang BC, Lee JK, Jeong J, Che JH, Seok SH. Comparative absorption, distribution, and excretion of titanium dioxide and zinc oxide nanoparticles after repeated oral administration. Part Fibre Toxicol. 2013;10:9.

Groschwitz KR, Hogan SP. Intestinal barrier function: molecular regulation and disease pathogenesis. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2009;124:3–20.

Collins AR, Ma AG, Duthie SJ. The kinetics of repair of oxidative DNA damage (strand breaks and oxidised pyrimidines) in human cells. Mutat Res. 1995;336:69–77.

Karlsson HL. The comet assay in nanotoxicology research. Anal Bioanal Chem. 2010;398:651–66.

IARC. Carbon Black, Titanium Dioxide, and Talc. In: IARC Monographs on the Evaluation of Carcinogenic Risks to Humans. World Health Organization, vol. 93. Lyon: IARC; 2010.

Jacobs JF, van de Poel I, Osseweijer P. Sunscreens with titanium dioxide (TiO2) nano-particles: a societal experiment. Nanoethics. 2010;4:103–13.

Prasad RY, Wallace K, Daniel KM, Tennant AH, Zucker RM, Strickland J, Dreher K, Kligerman AD, Blackman CF, Demarini DM. Effect of treatment media on the agglomeration of titanium dioxide nanoparticles: impact on genotoxicity, cellular interaction, and cell cycle. ACS Nano. 2013;7:1929–42.

Vranic S, Gosens I, Jacobsen NR, Jensen KA, Bokkers B, Kermanizadeh A, Stone V, Baeza-Squiban A, Cassee FR, Tran L, Boland S. Impact of serum as a dispersion agent for in vitro and in vivo toxicological assessments of TiO2 nanoparticles. Arch Toxicol. 2017;91:353–63.

Liu X, Chen G, Su C. Effects of material properties on sedimentation and aggregation of titanium dioxide nanoparticles of anatase and rutile in the aqueous phase. J Colloid Interface Sci. 2011;363:84–91.

Raza G, Amjad M, Kaur I, Baalousha M, Lead J, Wen D. Stability and aggregation kinetics of titania nanomaterials under environmentally realistic conditions. Environ Sci Technol. 2016;50:8462–72.

Warheit DB, Sayes CM, Reed KL. Nanoscale and fine zinc oxide particles: can in vitro assays accurately forecast lung hazards following inhalation exposures? Environ Sci Technol. 2009;43:7939–45.

Dorier M, Béal D, Marie-Desvergne C, Dubosson M, Barreau F, Houdeau E, Herlin-Boime N, Carriere M. Continuous in vitro exposure of intestinal epithelial cells to E171 food additive causes oxidative stress, inducing oxidation of DNA bases but no endoplasmic reticulum stress. Nanotoxicology. 2017;11:751–61.

Brun E, Barreau F, Veronesi G, Fayard B, Sorieul S, Chanéac C, Carapito C, Rabilloud T, Mabondzo A, Herlin-Boime N, Carrière M. Titanium dioxide nanoparticle impact and translocation through ex vivo, in vivo and in vitro gut epithelia. Part Fibre Toxicol. 2014;11:13.

Koeneman BA, Zhang Y, Westerhoff P, Chen Y, Crittenden JC, Capco DG. Toxicity and cellular responses of intestinal cells exposed to titanium dioxide. Cell Biol Toxicol. 2010;26:225–38.

Faust JJ, Masserano BM, Mielke AH, Abraham A, Capco DG. Engineered nanoparticles induced brush border disruption in a human model of the intestinal epithelium. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2014;811:55–72.

Faust JJ, Doudrick K, Yang Y, Westerhoff P, Capco DG. Food grade titanium dioxide disrupts intestinal brush border microvilli in vitro independent of sedimentation. Cell Biol Toxicol. 2014;30:169–88.

Guo Z, Martucci NJ, Moreno-Olivas F, Tako E, Mahler GJ. Titanium dioxide nanoparticle ingestion alters nutrient absorption in an in vitro model of the small intestine. NanoImpact. 2017;5:70–82.

Song ZM, Chen N, Liu JH, Tang H, Deng X, Xi WS, Han K, Cao A, Liu Y, Wang H. Biological effect of food additive titanium dioxide nanoparticles on intestine: an in vitro study. J Appl Toxicol. 2015;35:1169–78.

Chen J, Zhou H, Santulli AC, Wong SS. Evaluating cytotoxicity and cellular uptake from the presence of variously processed TiO2 nanostructured morphologies. Chem Res Toxicol. 2010;23:871–9.

Schneider T, Westermann M, Glei M. In vitro uptake and toxicity studies of metal nanoparticles and metal oxide nanoparticles in human HT29 cells. Arch Toxicol. 2017;91(11):3517–27.

Martirosyan A, Schneider YJ. Engineered nanomaterials in food: implications for food safety and consumer health. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2014;11:5720–50.

Chen T, Yan J, Li Y. Genotoxicity of titanium dioxide nanoparticles. J Food Drug Anal. 2014;22:95–104.

Carriere M, Sauvaigo S, Douki T, Ravanat JL. Impact of nanoparticles on DNA repair processes: current knowledge and working hypotheses. Mutagenesis. 2017;32:203–13.

Zijno A, De Angelis I, De Berardis B, Andreoli C, Russo MT, Pietraforte D, Scorza G, Degan P, Ponti J, Rossi F, Barone F. Different mechanisms are involved in oxidative DNA damage and genotoxicity induction by ZnO and TiO2 nanoparticles in human colon carcinoma cells. Toxicol in Vitro. 2015;29:1503–12.

Proquin H, Rodríguez-Ibarra C, Moonen CG, Urrutia Ortega IM, Briedé JJ, de Kok TM, van Loveren H, Chirino YI. Titanium dioxide food additive (E171) induces ROS formation and genotoxicity: contribution of micro and nano-sized fractions. Mutagenesis. 2017;32:139–49.

Vila L, García-Rodríguez A, Cortés C, Velázquez A, Xamena N, Sampayo-Reyes A, Marcos R, Hernández A. Effects of cerium oxide nanoparticles on differentiated/undifferentiated human intestinal Caco-2 cells. Chem Biol Interact. 2018;283:38–46.

Vandebriel RJ, Vermeulen JP, van Engelen LB, de Jong B, Verhagen LM, de la Fonteyne-Blankestijn LJ, Hoonakker ME, de Jong WH. The crystal structure of titanium dioxide nanoparticles influences immune activity in vitro and in vivo. Part Fibre Toxicol. 2018;15:9.

Tada-Oikawa S, Ichihara G, Fukatsu H, Shimanuki Y, Tanaka N, Watanabe E, Suzuki Y, Murakami M, Izuoka K, Chang J, Wu W, Yamada Y, Ichihara S. Titanium dioxide particle type and concentration influence the inflammatory response in Caco-2 cells. Int J Mol Sci. 2016;17:576.

Acknowledgements

A. Garcia-Rodriguez and L. Vila were funded by postgraduate fellowships from the Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona and the Generalitat de Catalunya, respectively.

Funding

This investigation has been partially supported by the Ministry of Economy and Competition (SAF2015–63519-R).

Availability of data and materials

The data supporting our conclusions is included in the main body of the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

RM, AH and CC designed the experimental approach and wrote the manuscript. AGR and LV performed all the experimental part, including the statistical analyses. All authors reviewed and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declared that they have no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Additional file

Additional file 1:

Table S1. Primer sequences. Table S2. Interconversion of the used concentrations. The relationships between μg/mL and μg/cm2 are indicated. Figure S1. Monolayer confirmation of the intestinal in vitro model, Caco-2/HT29. Transversal cuts of the Caco-2/HT29 barrier stained in Alcian Blue (A and C). Transversal cuts of Caco-2 monocultures (B and D) stained in Hematoxylin and Eosin. Figure S2. Dynamic light scattering characterization of the NP’s over the incubation time. Hydrodynamic size for TiO2NPs-S (A), TiO2NPs-R (B), and TiO2NPs-W (C), suspended in DMEM cell culture medium at concentrations ranging from 12.5 to 350 μg/mL. Bars that do not share any letter are significantly different according to the one-way ANOVA with a Tukey’s post-test (P < 0.05). Data is represented as mean ± SD. Figure S3. Three-dimensional confocal image of the Caco-2/HT29 co-culture exposed to 150 μg/mL of TiO2NPs-Wires. Cell nuclei (blue) were stained with Hoechst and mucus (red) stained with WGA. NPs were visualized by reflection and marked with a green mask. NPs-cell nucleus interactions are indicated with white circles. Images were processed with the Imaris 7.2.1 software. Figure S4. Confocal images of the reflected NPs found in the collected basolateral medium after exposing the Caco-2/HT29 co-culture barrier to 150 μg/mL of TiO2NPs. (DOCX 3832 kb)

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

García-Rodríguez, A., Vila, L., Cortés, C. et al. Effects of differently shaped TiO2NPs (nanospheres, nanorods and nanowires) on the in vitro model (Caco-2/HT29) of the intestinal barrier. Part Fibre Toxicol 15, 33 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12989-018-0269-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12989-018-0269-x