Abstract

Background

Sjögren syndrome (SS) is a rare disease in pediatrics, and little attention has been paid to the clinical feature in these patients. To date, there are few cases concern about neurological and nephrological disorders in childhood Sjögren syndrome. We describe a case of Sjögren syndrome in a 12-year-old girl who developed neurological disorders and interstitial nephritis and review the literature currently available on this topic.

Case presentation

A 12-year-old girl was admitted to our hospital for arthritis and glucosuria. She was required to do labial gland and renal biopsy, because the positive for anti-nuclear antibody and anti-Sjögren syndrome B (anti-SSB) antibody. Then the biopsy was performed revealing the lymphocytic infiltrate in the small area and renal tubular interstitial damage,thus the diagnosis of Sjögren syndrome with tubular interstitial damage was made. Three months later, she presented again with headache, fever, nausea, vomiting and was recovered without drug therapy. Based on the patient’s medical history, laboratory and imaging examination, and treatment, we speculate that the disorders of the nervous system were caused by the Sjögren syndrome. The girl has stable renal function and no residual nervous system damage in the next 1.5 years, but she underwent low dose prednisone therapy because of persistent renal glucosuria.

Conclusions

Nephrological disorders and neurological involvement are rare manifestations of Sjögren syndrome in children, and rarely presented as the initial symptoms. It should be suspected in children presenting with unexplained renal diseases, neurological abnormalities, or unexplained fever. Although there is no guidelines on the diagnosis and treatment of children Sjögren syndrome are currently available, early recognition and the appropriate treatment of renal damage and neurologic involvement would improve prognosis and prevent complications.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Sjögren syndrome (SS) is a complex autoimmune disease characterized by inflammation of the lacrimal and salivary glands leading to keratoconjunctivitis sicca and xerostomia with up to half of affected adults developing additional extraglandular manifestations. It is one of the most common autoimmune rheumatic diseases in adults, and organ systems associated with extraglandular manifestations (EGMs) are frequently involved, including the nervous, pulmonary, and vascular system [1]. However, the incidence of primary SS in children is much lower than in adults, and the presentation of childhood Sjögren syndrome often differs between children and adults. To date, few cases of primary childhood SS combined with neurological disorders and nephrological damage have been reported in the literature. Here, we describe a case of juvenile Sjögren syndrome in a 12-year-old girl who developed arthralgia, neurological disorders, and interstitial nephritis.

Case presentation

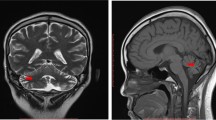

A 12-year-old girl presented to our clinic with left knee joint pain that had lasted for 7 days. The patient had no symptoms of fever, skin purpura, dry mouth, dry eyes, or parotitis. There was no past history of neck or face radiotherapy. Her physical examination revealed swelling in the left knee joint. Other physical findings were normal. Laboratory testing indicated normal complete blood counts and an erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) of 33 mm (0–20 mm/h). The patient tested positive for glucosuria upon urine screening, but was negative for hematuria and proteinuria. Then, we administered an oral glucose tolerance test (OGTT) and measured glycosylated hemoglobin A-1c(HbA1c) to evaluate glucose intolerance. Eventually,she was diagnosed as having renal glucosuria (RG) with normal glucose tolerance and normal HbA1c. She also tested positive for anti-nuclear antibody (ANA) (1:100), anti-Sjögren syndrome B (anti-SSB/Ro), Perinuclear antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody(P-ANCA)(1:10), and ESR (33 mm/h). Tests for anti-Sjögren syndrome A (anti-SSA/La), anti-Sm, anti-double stranded DNA (anti-dsDNA), anti-ribonnucleoprotein (anti-RNP), ani-Scl70, anti-phospholipid, anti-Jo-1, anti-myeloperoxidase antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody (anti-MPO-ANCA), rheumatoid factor (RF), anti-cyclic citrullinated peptide (anti-CCP) antibody, hepatitis B virus (HBV), hepatitis C virus (HCV), human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), IgG, IgA, IgM, C3, and C4 were negative or normal. Ophthalmological assessment revealed her schirmer’s test was positive. Ultrasonography of shallow lymph glands showed enlarged lymph nodes in the bilateral parotid gland. Histopathological analysis of minor salivary gland biopsy showed a lymphocytic infiltrate around the ducts and acinus in the small area (> 50 lymphocytes/4 mm2; Fig. 1). Renal biopsy showed tubular interstitial damage (Fig. 2). Light microscopy demonstrated previously unapparent proliferation of glomerular mesangial cells, increases in mesangial matrix, tubular interstitial and acinus damage, renal tubule epithelial cell swelling and degeneration, focal tubular atrophy, and tubular epithelial cell fusion (< 5%), while an interstitial lymphoplasmacytic infiltrate was not obvious. Electron microscopy revealed partial foot process fusion and no other significant ultrastructural abnormalities. Immunofluorescence showed no deposition of immunoglobulins (IgG, IgA, and IgM) or complement (C3, C4, and C1q), and the kappa and lambda chains were also negative. Based on the 2012 American College of Rheumatology Classification (ACR) criteria for Sjögren syndrome and kidney biopsy, she was diagnosed as primary Sjogren syndrome (pSS) with tubular interstitial damage. Her treatment consisting of celebrex (200 mg/d) and hydroxychloroquine (100 mg/d) was administered during the first week, with hydroxychloroquine (200 mg/d) and sulfasalazine enteric-coated tablets (400 mg/d) during the next half year of treatment. After the first 2 months of treatment, the girl’s joint pain was in complete remission and the complete blood counts and erythrocyte sedimentation rate were all normal. Three months later, she developed temporal headache, which was intermittent,being worst in the afternoon and relieved in the morning. The next day, she began to have a fever of 38.8 °C with nausea and vomiting. With worsening symptoms, the patient came to our hospital directly, where an MRI scan of the brain was normal (Fig. 3). Her physical examination showed superficial sensation disorder in the upper limbs and Kernig signs. Complete blood counts,c-reactive protein, procalcitonin, and the erythrocyte sedimentation rate were all unremarkable. For further investigation, lumbar puncture was performed, which revealed normal cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) pressure (> 125 mmH2O). High leucocyte counts of 30 cells 10^6 L with lymphocytic predominance (60%),a CSF glucose level of 3.1 mmol/L,a chlorine level of 126.1 mmol/L, and a CSF protein level of 206 mg/L were noted. Cytology of the CSF showed large lymphocytes and occasional histiocytic cells with normal morphology. Bacterial culture of the CSF was negative. Virus antibody testing of the CSF was negative for herpes simplex 1 and 2, cytomegalovirus, echovirus, coxsackievirus, and Epstein-Barr virus. Cryptococcus neoformans and Mycobacterium tuberculosis were also not found in the CSF. After these test results, she was diagnosed with aseptic meningoencephalitis but we could not exclude the possibility of viral meningitis. Therefore, the patient was treated with intravenous acyclovir. However,due to drug allergy,we stopped acyclovir treatment early. After 3 days, her headache and rash were significantly relieved. Based on the patient’s medical history, CSF examination, and treatment, we speculate that the disorders of the nervous system were more likely caused by the pSS. During the follow up of 1.5 years, her renal function was stable and no residual nervous system damage was apparent. She underwent low dose prednisone therapy (5-10 mg/d) for half a year because of persistent renal glucosuria.

Discussion and conclusions

We aimed to review all full-text, peer-review publications reporting childhood Sjogren syndrome with kidney or nerve damage. Records were identified from the PubMed, EMBASE databases. The search terms were primary Sjogren syndrome, child, children, and childhood. Results were limited to case reports written in English. The search date was December 23, 2019.

The initial search yielded 511 articles, after excluding the duplicate articles and reading titles and abstracts, 61 papers were then read in detail. Finally, 20 case reports were included in the literature review after extracting and analyzing the data from the articles (Fig. 4). The information that was extracted from the papers were as follows: references and year, age and gender of patient, symptoms at onset, dry eyes or mouth, parotitis,neurologic manifestation, renal damage, elevated ANA, presence of anti-SSA and SSB antibodies, ESR, RF, hyperglobulinemic, schirmer test, CSF, renal and salivary gland biopsy and immunomodulatory therapy (Table 1) [2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21].

Primary Sjogren syndrome is an autoimmune disorder that causes inflammation and injury to the exocrine glands [22], predominantly the lacrimal and salivary glands, resulting in dry eyes and mouth (sicca syndrome). There are few reports on childhood primary Sjogren syndrome, because SS is more common in adults than in children. The female to male ratio in adults is 9:1, and joint problems were present in 30–50%, while the incidence of kidney disease varies from 0.3% to up to 33.5%, depending on the study [23,24,25,26,27]. Other extraglandular diseases, such as cutaneous vasculitis, pulmonary manifestations, and peripheral nervous system manifestations occur in less than 10% [22]. In children, the sex ratio was 83–92.3% female [28, 29], and the most frequent symptom was parotid swelling,which was present in 42.3–53%, while central nervous system symptoms were present in 8.7%, and renal manifestations were present in 9.9–11.5%. Central nervous system and renal damage is uncommon in pediatric cases. We report a case of childhood pSS presenting with interstitial nephritis and neurological disorders.

We reviewed all full-text articles on childhood primary Sjogren syndrome and focused on cases of pediatric pSS with kidney or nerve damage (Table 1). In the review, 20/22 children were female, and 10/22 children had neurologic manifestations, often prior to the diagnosis of pSS. We reported a case in a female pediatric patient that had fever and superficial sensation disorder in the limbs months after pSS was diagnosed. Neurologic disorders included the peripheral nervous system (PNS) and the central nervous system (CNS), and involved fever, headache, mental disorder, gaze deviation, lethargy, muscle weakness, urinary incontinence, hypalgesia, difficulty with ambulation, or ptosis. Until now, no studies have been performed on the epidemiology and characteristics of neurological damage in children with pSS. The prevalence of neurologic manifestations in adults ranges between 28 and 67.5% according to the different study populations and the definition or methods for the detection of neuropathy [30,31,32]. The studies showed that 46–80% of adult patients with neurological symptoms developed such symptoms prior to the diagnosis of pSS [30, 31]. The frequency of constitutional symptoms and lung involvement was significantly higher in pSS with neurological involvement than in pSS without neurological involvement, and the articular symptoms were significantly less frequent in pSS with neurological involvement [33]. At present, the pathogenic mechanisms for most forms of neurological involvement in pSS have not been elucidated. However, several mechanisms have been considered to explain this involvement. In the development of PNS involvement in pSS patients, vascular or peripheral inflammatory infiltrates with or without necrosis may be found, and vasculitis of the vasa nervorum has also been proposed as a pathogenic mechanism [34,35,36,37,38]. These CNS disorders may be explained by three pathogenic factors. The first hypothesis involves the direct infiltration of the CNS by mononuclear cells [39]. The second hypothesis involves vascular injury that may be related to the presence of antineuronal antibodies and anti-Ro antibodies [40]. Finally, researchers [41,42,43] suggest that the underlying mechanism of CNS lesion development in pSS involves ischemia secondary to small vessel vasculitis.

In renal manifestations, the main damage in childhood pSS is tubulointerstitial nephritis (TIN), and the clinical features of renal involvement are proteinuria, hematuria, glucoseuria, or alkalineurine. A literature review of pediatric pSS showed that renal manifestations were present in 9.9%, including renal tubular acidosis (RTA), membranous glomerulonephritis (MGN), hypokalemia, and interstitial nephritis [28]. Glomerular damage is rare, and we only found three cases,one report a case of pSS with mesangial proliferative glomerulonephritis and IgA deposits [8], another report a girl with pSS complicated by MGN [15], the last one reported a case of pauci-immune crescentic glomerulonephritis [12]. It has been proposed that the course of renal impairment might be shorter in the interstitial nephritis group, and the incidence of cryoglobulinemia and low C4 might be higher in the glomerulonephritis (GN) group [9]. The prevalence of renal involvement in adult pSS has been reported to range from 1% in some large retrospective registries, to 5–14% in most European studies, and > 30% in a cohort of 573 Chinese patients [44]. Unlike children, the renal damage in adults is manifested by overt or latent distal RTA, nephrogenic diabetes insipidus, and rarely, proximal RTA [27, 44, 45]. The frequency of GN in adults varies from 16.6 to 58.2% depending on race, center, and number of cases [23, 24, 46,47,48]. In renal biopsies of GN, membranoproliferative glomerulonephritis (MPGN) secondary to cryoglobulinaemia is the most common type, and other pathological types include membranous nephropathy, IgA nephropathy, focal segmental glomerulosclerosis, minimal change disease, unspecified proliferative glomerulonephritis, crescentic glomerulonephritis, and global glomerulosclerosis [44]. A large cohort of adult pSS patients revealed that patients with TIN have a better prognosis and clinical outcome, while patients with GN have a less favorable prognosis and a higher risk of developing lymphoma, which is related to cryoglobulinemia .

From the review, except the girl we reported, 20 of 21 children were positive for ANA and anti-SSA, while, 8 out of 20 were anti-SSB negative. This result is consistent with previous observations that the positive rate of ANA and anti-SSA is higher than anti-SSB in adults and children [32, 49, 50]. From a systematic review of primary Sjogren syndrome in pediatric populations, the presence of anti-SSA (Ro), anti-SSB (La), and anti-nuclear antibodies (ANA) was positive in 36.4–84.6%, 27.3–65.4%, and 63.6–96.2%, respectively [50]. New research showed that patients positive for both anti-SSA and anti-SSB had a substantially higher risk of cerebral infarction and venous thromboembolism than the general population [51].

Meanwhile, we also found an interesting phenomenon, hyperglobulinemia presented in 12 cases, and 11/12 were IgG, only 3 cases were IgA. High IgG levels are a common feature of SS and might reflect greater B cell activation [52]. Research showed that patients with high IgG levels had a higher prevalence of purpura and immunological markers (ANA, RF, anti-SSA, and anti-SSB) [53]. All of the 3 cases with high IgA had renal damage, so we speculated whether IgA participated the pSS and kidney disease at the same time. Plasma cells producing IgA rather than IgG or IgM are dominantly observed in the salivary glands of SS patients [54]. Enrichment of anti-SS-B IgA antibodies in the saliva of patients with SS may suggest enhanced local synthesis of anti-SS-B IgA [55]. The presence of IgA autoantibodies against M3 muscarinic acetylcholine receptors is also considered to be a pathophysiological factor of primary SS [56]. These findings suggest that abnormal immunity of IgA production may attributable to SS, but unfortunately immunofluorescent findings of the 3 children indicated no deposition of IgA. More extensive investigations will be needed to support the hypothesis.

All the patients in our report received immunomodulatory therapy including glucocorticoid, azathioprine, rituximab, hydroxychloroquine, cyclophosphamide, mycophenolate mofetil, and methotrexate. At present, the treatment of childhood pSS presenting with renal and nerve damage lacks large-scale evidence-based medicine and is mostly based on clinical experience. Although the long-term outcome of renal damage in pediatric pSS is usually good, glucocorticoids were often used in pediatric cases with RTA and TIN, and chronic immunosuppression is needed for the glomerular involvement often associated with a progressive course [5, 7, 57]. Long term outcomes may be related to the improvement in overall survival rate, renal survival rate, and complete remission rate of renal disease in childhood pSS treated with immunosuppressive therapy. From our review, steroids (1 mg/kg/day) were often used as the initial immunosuppressive treatment in pediatric pSS patients with TIN or GN. However, the outcome of children presenting with neurological diseases in the review is relatively less favorable. All the cases here reported residual neurologic manifestations, even though these children received steroids (1–2 mg/kg/day) or other immunosuppressive therapies. Kornitze [3] reviewed reported cases of childhood Sjogren syndrome with CNS complications in which 10 of 10 cases received steroid therapy and 7 of 10 patients had residual neurological deficits at follow-up. The effectiveness of glucocorticoids combined with other immunosuppressants in children still requires further study.

The frequency of renal damage and neurologic involvement in childhood pSS is much lower than in adults, and the clinical symptoms may be significantly different than what is seen in adults. If children present with unexplained renal diseases, neurological abnormalities, and unexplained fever, pSS should be considered. Special serological screening tests should be added to routine laboratory tests, while kidney biopsy may contribute to assessing the extent of renal damage and the need for immunomodulatory therapy. Early recognition and the appropriate treatment of renal damage and neurologic involvement would improve prognosis and prevent complications. Long term follow-up is essential for these children due to the possibility of rapid progression.

Availability of data and materials

Data sharing not applicable to this article as no datasets were generated or analyzed during the current study.

Abbreviations

- SS:

-

Sjögren syndrome

- pSS:

-

primary Sjogren syndrome

- EGMs:

-

extraglandular manifestations

- ESR:

-

erythrocyte sedimentation rate

- OGTT:

-

oral glucose tolerance test

- HbA1c:

-

glycosylated hemoglobin A-1c

- RG:

-

renal glucosuria

- ANA:

-

anti-nuclear antibody

- anti-SSB:

-

anti-Sjögren syndrome B

- P-ANCA:

-

perinuclear antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody

- anti-SSA:

-

anti-Sjögren syndrome A

- anti-dsDNA:

-

anti-double stranded DNA

- anti-RNP:

-

anti-ribonnucleoprotein

- anti-MPO-ANCA:

-

anti-myeloperoxidase antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody

- RF:

-

rheumatoid factor

- anti-CCP:

-

anti-cyclic citrullinated peptide

- HBV:

-

hepatitis B virus

- HCV:

-

hepatitis C virus

- HIV:

-

human immunodeficiency virus

- CSF:

-

cerebrospinal fluid

- PNS:

-

peripheral nervous system

- CNS:

-

central nervous system

- TIN:

-

tubulointerstitial nephritis

- RTA:

-

renal tubular acidosis

- GN:

-

glomerulonephritis

- MGN:

-

membranous glomerulonephritis

- MPGN:

-

membranoproliferative glomerulonephritis

References

Ienopoli S, Carsons SE. Extraglandular manifestations of primary Sjogren’s syndrome. Oral Maxillofac Surg Clin North Am. 2014;26:91–9.

Matsui Y, Takenouchi T, Narabayashi A, Ohara K, Nakahara T, Takahashi T. Childhood Sjogren syndrome presenting as acute brainstem encephalitis. Brain Dev. 2016;38:158–62.

Kornitzer JM, Kimura Y, Janow GL. Primary Sjogren syndrome in a child with a Neuromyelitis Optica Spectrum disorder. J Rheumatol. 2016;43:1260–1.

Arabshahi B. Devic disease in a child with primary Sjogren syndrome. J Child Neurol. 2006;21:284–6.

Bogdanovic R, Basta-Jovanovic G, Putnik J, Stajic N, Paripovic A. Renal involvement in primary Sjogren syndrome of childhood: case report and literature review. Mod Rheumatol. 2013;23:182–9.

Kumon K, Satake A, Mizumoto M, Kobayashi I, Ishikawa N. A case of sensory neuropathy associated with childhood Sjogren syndrome. Eur J Pediatr. 2000;159:630–1.

Pessler F, Emery H, Dai L, Wu YM, Monash B, Cron RQ, Pradhan M. The spectrum of renal tubular acidosis in paediatric Sjogren syndrome. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2006;45:85–91.

Jung SK, Park KH, Yim HE, Yoo KH, Hong YS, Lee JW, Won NH. Primary Sjogren’s syndrome with mesangial proliferative glomerulonephritis and IgA deposits in a child. Pediatr Nephrol. 2010;25:567–8.

Igarashi T, Itoh Y, Shimizu A, Igarashi T, Yoshizaki K, Fukunaga Y. A case of juvenile Sjogren’s syndrome with interstitial nephritis. J Nippon Med Sch. 2012;79:286–90.

Gottfried JA, Finkel TH, Hunter JV, Carpentieri DF, Finkel RS. Central nervous system Sjogren’s syndrome in a child: case report and review of the literature. J Child Neurol. 2001;16:683–5.

Wong S, Pollock AN, Burnham JM, Sherry DD, Dlugos DJ. Acute cerebellar ataxia due to Sjogren syndrome. Neurology. 2004;62:2332–3.

Kagan M, Bervina N, Vorobyeva O, Wouters C, Levtchenko E. Pauci-immune crescentic glomerulonephritis complicating Sjogren’s syndrome in a 12-year-old girl. Pediatr Nephrol. 2011;26:991–2.

DeGuzman M, Fishman MA, Lewis RA, McCluggage C, Warren RW, Finegold MJ. Chronic neurologic disease with visual, gait, and bladder problems in a male teenager. J Pediatr. 1998;132:742–7.

Skalova S, Minxova L, Slezak R. Hypokalaemic paralysis revealing Sjogren’s syndrome in a 16-year old girl. Ghana Med J. 2008;42:124–8.

Yoshida K, Suzuki J, Kume K, Suzuki S, Isome M, Kato K, Suzuki H. Sjogren’s syndrome with membranous glomerulonephritis detected by urine screening of schoolchildren. Acta Paediatr Jpn. 1996;38:533–6.

Berman JL, Kashii S, Trachtman MS, Burde RM. Optic neuropathy and central nervous system disease secondary to Sjogren’s syndrome in a child. Ophthalmology. 1990;97:1606–9.

Zawadzki J. Permeability defect with bicarbonate leak as a mechanism of immune-related distal renal tubular acidosis. Am J Kidney Dis. 1998;31:527–32.

Kobayashi I, Furuta H, Tame A, Kawamura N, Kojima K, Endoh M, Okano M, Sakiyama Y. Complications of childhood Sjogren syndrome. Eur J Pediatr. 1996;155:890–4.

Chang YC, Huang CC, Chiou YY, Yu CY. Renal tubular acidosis complicated with hypokalemic periodic paralysis. Pediatr Neurol. 1995;13:52–4.

Ohlsson V, Strike H, James-Ellison M, Tizard EJ, Ramanan AV. Renal tubular acidosis, arthritis and autoantibodies: primary Sjogren’s syndrome in childhood. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2006;45:238–40.

Hoshina T, Yamaguchi Y, Ohga S, Kira R, Ishimura M, Takada H, Tanaka T, Hara T. Sjogren’s syndrome-associated meningoencephalomyelitis: cerebrospinal fluid cytokine levels and therapeutic utility of tacrolimus. J Neurol Sci. 2008;267:182–6.

Fogo AB, Lusco MA, Najafian B, Alpers CE. AJKD atlas of renal pathology: kidney disease in primary Sjogren syndrome. Am J Kidney Dis. 2017;69:e29–30.

Maripuri S, Grande JP, Osborn TG, Fervenza FC, Matteson EL, Donadio JV, Hogan MC. Renal involvement in primary Sjogren’s syndrome: a clinicopathologic study. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2009;4:1423–31.

Goules AV, Tatouli IP, Moutsopoulos HM, Tzioufas AG. Clinically significant renal involvement in primary Sjogren’s syndrome: clinical presentation and outcome. Arthritis Rheum. 2013;65:2945–53.

Ramos-Casals M, Brito-Zeron P, Solans R, Camps MT, Casanovas A, Sopena B, Diaz-Lopez B, Rascon FJ, Qanneta R, Fraile G, et al. Systemic involvement in primary Sjogren’s syndrome evaluated by the EULAR-SS disease activity index: analysis of 921 Spanish patients (GEAS-SS Registry). Rheumatology (Oxford). 2014;53:321–31.

Yang HX, Wang J, Wen YB, Fei YY, Jiang MD, Zhou MY, Zhang W, Li H, Li XM, Zhang FC, et al. Renal involvement in primary Sjogren’s syndrome: a retrospective study of 103 biopsy-proven cases from a single center in China. Int J Rheum Dis. 2018;21:223–9.

Wang J, Wen Y, Zhou M, Shi X, Jiang L, Li M, Yu Y, Li X, Li X, Zhang W, et al. Ectopic germinal center and megalin defect in primary Sjogren syndrome with renal Fanconi syndrome. Arthritis Res Ther. 2017;19:120.

Means C, Aldape MA, King E. Pediatric primary Sjogren syndrome presenting with bilateral ranulas: a case report and systematic review of the literature. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 2017;101:11–9.

Yokogawa N, Lieberman SM, Sherry DD, Vivino FB. Features of childhood Sjogren’s syndrome in comparison to adult Sjogren’s syndrome: considerations in establishing child-specific diagnostic criteria. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2016;34:343–51.

Teixeira F, Moreira I, Silva AM, Vasconcelos C, Farinha F, Santos E. Neurological involvement in primary Sjogren syndrome. Acta Reumatol Port. 2013;38:29–36.

Morreale M, Marchione P, Giacomini P, Pontecorvo S, Marianetti M, Vento C, Tinelli E, Francia A. Neurological involvement in primary Sjogren syndrome: a focus on central nervous system. PLoS One. 2014;9:e84605.

Moreira I, Teixeira F, Martins Silva A, Vasconcelos C, Farinha F, Santos E. Frequent involvement of central nervous system in primary Sjogren syndrome. Rheumatol Int. 2015;35:289–94.

Massara A, Bonazza S, Castellino G, Caniatti L, Trotta F, Borrelli M, Feggi L, Govoni M. Central nervous system involvement in Sjogren’s syndrome: unusual, but not unremarkable--clinical, serological characteristics and outcomes in a large cohort of Italian patients. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2010;49:1540–9.

Mellgren SI, Conn DL, Stevens JC, Dyck PJ. Peripheral neuropathy in primary Sjogren’s syndrome. Neurology. 1989;39:390–4.

Kaltreider HB, Talal N. The neuropathy of Sjogren’s syndrome. Trigeminal nerve involvement. Ann Intern Med. 1969;70:751–62.

Chai J, Logigian EL. Neurological manifestations of primary Sjogren’s syndrome. Curr Opin Neurol. 2010;23:509–13.

Gono T, Kawaguchi Y, Katsumata Y, Takagi K, Tochimoto A, Baba S, Okamoto Y, Ota Y, Yamanaka H. Clinical manifestations of neurological involvement in primary Sjogren’s syndrome. Clin Rheumatol. 2011;30:485–90.

Tobon GJ, Pers JO, Devauchelle-Pensec V, Youinou P. Neurological disorders in primary Sjogren’s syndrome. Autoimmune Dis. 2012;2012:645967.

Bakchine S, Duyckaerts C, Hassine L, Chaunu MP, Turell E, Wechsler B, Chain F. Central and peripheral neurologic lesions in primary Gougerot-Sjogren syndrome. Clinicopathological study of a case. Rev Neurol (Paris). 1991;147:368–75.

Alexander EL, Ranzenbach MR, Kumar AJ, Kozachuk WE, Rosenbaum AE, Patronas N, Harley JB, Reichlin M. Anti-Ro (SS-A) autoantibodies in central nervous system disease associated with Sjogren’s syndrome (CNS-SS): clinical, neuroimaging, and angiographic correlates. Neurology. 1994;44:899–908.

Molina R, Provost TT, Alexander EL. Peripheral inflammatory vascular disease in Sjogren’s syndrome. Association with nervous system complications. Arthritis Rheum. 1985;28:1341–7.

lexander E, Provost TT. Sjogren’s syndrome. Association of cutaneous vasculitis with central nervous system disease. Arch Dermatol. 1987;123:801–10.

Alexander EL, Provost TT, Sanders ME, Frank MM, Joiner KA. Serum complement activation in central nervous system disease in Sjogren’s syndrome. Am J Med. 1988;85:513–8.

Francois H, Mariette X. Renal involvement in primary Sjogren syndrome. Nat Rev Nephrol. 2016;12:82–93.

Evans R, Zdebik A, Ciurtin C, Walsh SB. Renal involvement in primary Sjogren’s syndrome. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2015;54:1541–8.

Ren H, Wang WM, Chen XN, Zhang W, Pan XX, Wang XL, Lin Y, Zhang S, Chen N. Renal involvement and followup of 130 patients with primary Sjogren’s syndrome. J Rheumatol. 2008;35:278–84.

Lin DF, Yan SM, Yan Z, Wen Z, Meng-Tao LI, Zeng XF, Zhang FC, Yi D. Clinical and prognostic characteristics of 573 cases of primary Sj(o)gren’s syndrome. J Chin Med. 2010;123:3252–7.

Kidder D, Rutherford E, Kipgen D, Fleming S, Geddes C, Stewart GA. Kidney biopsy findings in primary Sjogren syndrome. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2015;30:1363–9.

Chen PH, Yang YH, Lin YT, Lee JH, Wang LC, Yu HH, Chiang BL. Clinical characteristics of children with positive anti-SSA/SSB antibodies. Rheumatol Int. 2014;34:1123–7.

Virdee S, Greenan-Barrett J, Ciurtin C. A systematic review of primary Sjogren’s syndrome in male and paediatric populations. Clin Rheumatol. 2017;36:2225–36.

Mofors J, Holmqvist M, Westermark L, Bjork A, Kvarnstrom M, Forsblad-d’Elia H, Magnusson Bucher S, Eriksson P, Theander E, Mandl T, et al. Concomitant Ro/SSA and La/SSB antibodies are biomarkers for the risk of venous thromboembolism and cerebral infarction in primary Sjogren’s syndrome. J Intern Med. 2019;286:458–68.

Kang KY, Kim HO, Kwok SK, Ju JH, Park KS, Sun DI, Jhun JY, Oh HJ, Park SH, Kim HY. Impact of interleukin-21 in the pathogenesis of primary Sjogren’s syndrome: increased serum levels of interleukin-21 and its expression in the labial salivary glands. Arthritis Res Ther. 2011;13:R179.

Zhao Y, Li Y, Wang L, Li XF, Huang CB, Wang GC, Zhang XW, Zhang ZL, Zhang X, Xiao WG, et al. Primary Sjogren syndrome in Han Chinese: clinical and immunological characteristics of 483 patients. Medicine (Baltimore). 2015;94:e667.

Berra A, Sterin-Borda L, Bacman S, Borda E. Role of salivary IgA in the pathogenesis of Sjogren syndrome. Clin Immunol. 2002;104:49–57.

Speight PM, Cruchley A, Williams DM. Quantification of plasma cells in labial salivary glands: increased expression of IgM in Sjogren’s syndrome. J Oral Pathol Med. 1990;19:126–30.

Horsfall AC, Rose LM, Maini RN. Autoantibody synthesis in salivary glands of Sjogren’s syndrome patients. J Autoimmun. 1989;2:559–68.

Schuetz C, Prieur AM, Quartier P. Sicca syndrome and salivary gland infiltration in children with autoimmune disorders: when can we diagnose Sjogren syndrome? Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2010;28:434–9.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Allen Cusack,PhD & MD for English language editing.

Ethics approval and consent to participation

Parental informed consent for publication was obtained.

Funding

No funding.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

JZ wrote the first draft of the manuscript and contributed to patient management. YZ contributed to patient management and to the literature review. MZ and XG contributed to the literature review. ZZ performed the radiological studies. QC critically revised the manuscript and supervised patient management. All the authors read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Consent for publication

Written informed consent was obtained from the patient’s legal guardians for publication of this case report and any accompanying images.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhao, J., Chen, Q., Zhu, Y. et al. Nephrological disorders and neurological involvement in pediatric primary Sjogren syndrome:a case report and review of literature. Pediatr Rheumatol 18, 39 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12969-020-00431-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12969-020-00431-y