Abstract

Background

Making tobacco products associated with lower risks available to smokers who would otherwise continue smoking is recognized as an important strategy towards addressing smoking-related harm. Predicting use behavior is an important major component of product risk assessment. In this context, risk perception is a possible factor driving tobacco product uptake and use. As prior to market launch real-world actual product use cannot be observed, assessing risk perception can provide predictive information. Considering the lack of suitable validated self-report instruments, the development of a new instrument was undertaken to quantify perceived risks of tobacco and nicotine-containing products by adult smokers, former smokers and never-smokers.

Methods

Initial items were constructed based on a literature review, focus groups and expert opinion. Data for scale formation and assessment were obtained through two successive US-based web surveys (n = 2020 and 1640 completers, respectively). Psychometric evaluation was based on Rasch Measurement Theory and Classical Test Theory.

Results

Psychometric evaluation supported the formation of an 18-item Perceived Health Risk scale and a 7-item Perceived Addiction Risk scale: item response option thresholds were ordered correctly for all items; item locations in each scale were spread out (coverage range 75–87%); scale reliability was supported by high person separation indices > 0.93, Cronbach’s alpha > 0.98 and Corrected Item-Total Correlations > 0.88; and no differential item functioning was present. Construct validity evaluations met expectations through inter-scale correlations and findings from known-group comparisons.

Conclusions

The Perceived Risk Instrument is a psychometrically robust instrument applicable for general and personal risk perception measurement, for use in different types of products (including cigarettes, nicotine replacement therapy, potential Modified Risk Tobacco Products), and for different smoking status groups (i.e., current smokers with and without intention to quit, former smokers, never smokers).

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Cigarette smoking causes many serious diseases [1]. The best way to reduce the adverse health consequences of smoking is to stop smoking [2]. For smokers who choose to continue to smoke, reducing exposure to toxicants and safer delivery of nicotine are among the strategies that have been introduced to reduce the risk of smoking-related diseases [3]. As new tobacco products, which may be a less harmful alternative to continued smoking, become increasingly available (e.g., smokeless tobacco, e-cigarettes, heat-not-burn products), this has created new challenges for policy makers [4]. In the United States (US), a regulatory framework has been put in place since 2012 for manufacturers to market a modified risk tobacco product (MRTP) – that is, any tobacco product that is sold or distributed for use to reduce the risk of tobacco-related disease associated with commercially marketed tobacco products [5].

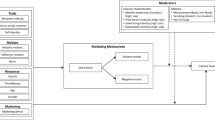

As population health impact is a function of product risk and product uptake distribution, predicting product use prior to market launch is an important component of product risk assessment. In particular, the effect that an MRTP’s marketing will have on consumer understanding and perception is an important consideration as it is essential that the product communication materials be an accurate, non-misleading, and scientifically substantiated reflection of the product characteristics, permitting adult smokers to understand the risks and benefits compared to other tobacco products, without encouraging non-smokers to initiate or reinitiate tobacco use [6]. Part of validating these requirements is the assessment of consumer risk perception, as such perceptions might be crucial determinants of product use among both current tobacco users and non-users [7, 8]. At the same time, valid instruments to measure consumer responses to tobacco products are largely lacking [9] and there is currently no self-report instrument available that would allow the quantification of perceived risks of different tobacco and nicotine-containing products [10].

A self-report instrument should be: (1) appropriate to capture the individual perspective and include relevant and meaningful domains; (2) applicable across a wide range of tobacco and nicotine-containing products; (3) suitable for a range of respondent groups such as users and non-users; (4) underpinned by an appropriate psychometric measurement model; (5) straightforward to administer and score; and (6) applicable for clinical and population-based studies. These criteria reflect current standards of valid measurement in terms of qualitative aspects (i.e., relevant and meaningful domains as evidence of content validity) and quantitative requirements of construct validity (i.e., psychometric criteria), as well as regarding the practicability and usefulness. Other desirable psychometric properties include: unidimensionality (meaning that there is one underlying latent variable accounting for the observed item scores); separation of person and item parameter estimates (allowing for a detailed examination of the extent to which a set of items proposed to form a scale separates participants and allows for precise measurement); and lack of item bias with respect to subpopulations (thus the properties of the participants, their distribution and other characteristics, should not impact on the item properties). These psychometric properties support a metrological framework for the social sciences, and can be realized by using the Rasch model which: provides parameter separability, statistical sufficiency, and specific objectivity [11]; is embedded in Georg Rasch’s general philosophy of measurement [12]; and, is subsequently formalized in the language of measurement traceability [13] and uncertainty [14].

Previous research [10] showed the measurement of perceived risks typically relies on, at most, a small number of self-report items [9, 15,16,17,18,19,20,21]. However, single items, or short scales, do not allow for a comprehensive measurement of risk perception, and provide little insight into the underlying perceived risk continuum. Also, short scales tend to lack reliability, and, by implication, measurement precision [22]. And psychometric measurement models cannot be easily applied, limiting the quantitative assessment of construct validity. Current measurements of perceived risks are typically product-specific (e.g., for cigarettes) [15, 21, 23,24,25] or rely on a single statement of comparative risk between a pair of products [26, 27]. In the context of an MRTP assessment, flexible and indirect comparison is needed between all tobacco- or nicotine-containing products [5, 28]. Finally, existing approaches tend to focus on current users (e.g., cigarette smokers). Considering the lack of suitable validated self-report instruments, the objective of the present work was to develop a new instrument to quantify perceived risks of tobacco and nicotine-containing products by adult smokers, former smokers and never-smokers. Here, we describe the overall process and subsequently focus on the development of two scales addressing Perceived Health Risk and Perceived Addiction Risk.

Methods

Development of the draft instrument and pre-testing

To support the development of a conceptual framework and subsequent item generation, a literature review and a series of qualitative studies were conducted, including focus groups and expert opinion elicitation. All this qualitative research is described in detailed somewhere else [10], and is only briefly summarized below. Prior to formal psychometric evaluation, cognitive debriefing interviews (CDIs) and a pilot testing were conducted to ascertain the good comprehension and acceptability of the draft instrument.

Literature review

A systematic search of studies related to risk perception and tobacco products published between January 2000 and September 2012 was conducted in Embase® and MEDLINE®. Further sources were identified by three public health experts,Footnote 1 covering quality of life research, consumer risk perception research, and scale development. A total of 136 papers were identified by database search, 36 by experts, leading to 42 papers being selected for a detailed review. The literature review revealed four broad domains with perceived health risk (including addiction risk) being the most widely captured domain (referenced in 24 papers). Less frequently, social, financial, and time-related aspects of perceived risk were addressed (referenced in 8, 2, and 2 papers, respectively).

Focus groups

In order to gain insights into the respondents’ perspectives, 29 focus groups were conducted in the US, UK, Italy, and Japan. Smoking status groups were defined in accordance with the World Health Organization (WHO) guidelines [29] and the Prochaska and DiClemente stages of change model [30] (see Table 1 for demographics). In the focus groups, conventional cigarette, electronic cigarette and a nicotine replacement therapy (NRT) samples were used to stimulate participants to discuss risks associated to tobacco and nicotine-containing products. The emerging domains showed wide overlap across countries. Health and addiction risks dominated the concepts in all countries except in Japan, where societal/social risks and material/financial risks were about equally prevalent.

Expert opinion

Four expertsFootnote 2 in nicotine addiction, motivational aspects of consumer perception, and epidemiology proposed relevant themes and reviewed the identified domains. Expert opinions widely agreed with the findings of the literature review and the focus groups and facilitated the consolidation of all qualitative input to the conceptual framework. However, experts recommended health risk to others as a separate aspect of health risk, and addiction risk as a domain on its own. The final conceptual framework thus comprised five potential domains:

-

Perceived Health Risk to Self. The perceived negative risk (or impact) of product use to the user’s physical health, ranging from minor immediate concrete manifestations of health risk (e.g., having poor gum health) to more serious long-term ones (e.g., having lung cancer);

-

Perceived Addiction Risk. The perceived negative risk (or impact) that product use may have on the user’s sense of being addicted to using the product;

-

Perceived Health Risk to Others. The perceived negative risk (or impact) to the physical health of nonsmokers when being around during product use (not to be confused with the category of general risk, i.e., the risk of active use of tobacco products for active users in general);

-

Perceived Social Risk. The perceived negative risk (or impact) that product use will affect interpersonal interactions adversely or how the user is perceived by others;

-

Perceived Practical Risk. The perceived negative risk (or impact) that product use may have on the user’s time and finances.

Item generation

Two versions of a sentence stem presented at the top of each page were generated for all items within a domain. For Perceived Health Risk to Self, one stem referred to the personal risk to the individual respondent (e.g., with regards to cigarette smoking: “What do you think is the risk, if any, to you personally of getting the following (sometime during your lifetime) because you smoke cigarettes …”). The other stem referred to the risk to a user of a product in general (“In general, what do you think is the risk, if any, to smokers of getting the following (sometime during their lifetime) because of smoking cigarettes …”). Similar sentence stems were used for other domains. The items themselves consisted of brief expressions mostly in the order of four to six words, e.g., “having mouth or throat cancer” or “having reduced stamina”.

A five-point fully verbalized rating scale ranging from “no risk” to “very high risk” was used to allow for expressing a medium level of perceived risk (“moderate risk”). The option “don’t know” was added for respondents not relating to some items and therefore lacking a perception. Two English language versions of the new proposed Perceived Risk Instrument (PRI) were drafted for personal (PRI-P) and general risk assessment (PRI-G). The intention was that the PRI would be applicable to: (1) adult smokers with intention to quit, adult smokers with no intention to quit, adult former smokers, and adult never smokers; and to (2) tobacco and nicotine-containing products as well as Cessation (perceived risk from having smoked in the past).

Cognitive debriefing interviews

The draft versions of the PRI-P and PRI-G were presented to UK and US participants using the same sampling frame as for the focus groups (Table 1 for demographics). Overall, participants found the content to be comprehensive, the stems to be clear, and the items and response formats straightforward to complete. Importantly, participants could discriminate between the two versions of the PRI and to assess personal as well as general risks accordingly. A few minor changes were made to the draft version of the instrument, including: (1) the adjustment of stems for participants with different smoking status and for different product types; (2) the removal of two items in the health risk to others domain due to ambiguity and lack of relevance; and (3) improvements of the wording of some items.

In addition, feedback from never smokers suggested that it was challenging to assess their personal risk of products (specifically NRT) they would never consider using. This led to the decision not to administer the PRI-P to NRT and Cessation to never smokers. The final draft versions of the PRI comprised a total of 67 items each, related to five domains: Perceived Health Risk to Self (31 items); Perceived Health Risk to Others (3 items); Perceived Addiction Risk (11 items); Perceived Social Risk (13 items); and Perceived Practical Risk (9 items).

Pilot field testing

After the qualitative stage, the five-domain draft PRI was administered in a pilot study (web-survey with 233 completers) to assess the feasibility of developing the five scales in parallel. Floor effects (between 12 and 41%) occurred for perceived social and perceived practical risks when applied to products other than cigarettes (CCs). It was concluded that developing scales for perceived social and perceived practical risk would in all likelihood, at this stage, not result in properly targeted scales with a broad coverage of the latent continuum. Rather, additional qualitative research appeared to be necessary. This led to the decision to, for the time being, solely focus on perceived health and addiction risks for the psychometric evaluation of the PRI. Perceived health and addiction risks also were the most widely addressed domains of risk in the extant literature [10]. Therefore, the quantitative field tests were restricted to the three health-related domains, i.e., Perceived Health Risk to Self, Perceived Health Risk to Others, and Perceived Addiction Risk

Psychometric evaluation

For the psychometric evaluation of the draft PRI, two online cross-sectional surveys were conducted in the USA. Survey 1 served scale formation and item reduction, while Survey 2 was used for cross-validation of the PRI.

Design and procedure

Survey 1 and Survey 2 were designed as internet cross-sectional studies with stratified sampling of four subpopulations defined according to self-reported smoking status at the time of data collection. Respondents reporting having smoked at least 100 cigarettes in their lifetime and currently smoking at least one cigarette (no brand restrictions) per day (disregarding religious fasting) at the time of data collection were classified as adult current smokers. The latter were further divided into those with, and those without intention to quit, in accordance to Prochaska and DiClemente’s Stages of Change model [31]. Respondents reporting that they were former daily smokers and, at the time of study, had been quitting smoking more than 30 days ago, were classified as former smokers. Those who reported that they had never smoked at all, or who had never been daily smokers and had smoked less than 100 cigarettes in their lifetime, were classified as never smokers.

Within each smoking status group, quota sampling based on age, sex, and education was applied. A web-based data capture tool (i.e., Confirmit Horizons version 16) was used to gather responses from study participants from an opt-in proprietary database maintained by Toluna Group Ltd. (Wilton, Connecticut USA), consisting of individuals with expressed interest in participating in online survey research. The samples within each stratum were not fully representative in terms of exactly matching the structure of the US population. Rather, the sample composition served the purpose of scale development and satisfied the needs in this regard, such as adequate representation of each segment defined by the quota criteria.

In Survey 1, respondents completed the PRI for the assessment objects CC, the Tobacco Heating System (THS) 2.2 (a heat-not-burn Reduced Risk Product (RRP)Footnote 3 developed by Philip Morris Products S.A.), a nicotine patch and Cessation (defined as having successfully stopped smoking and not using any tobacco and nicotine-containing product). In Survey 2, E-cigarettes were added to the assessment and nicotine patch was replaced by nicotine replacement therapy (NRT) as a general category. Participants were quota-randomized to pre-determined sequences so that an equal number of participants of each demographic stratum would be exposed to a specific sequence of product assessment. A minimum of 1600 completers, with an equal representation of each of the four subpopulations defined by smoking status, was estimated as an appropriate sample size for psychometric evaluation for each survey [22, 32, 33].

Survey 1 (administered between February and March 2014) and Survey 2 (administered between May and June 2014) were both approved by the New England Institutional Review Board and the participants received complete information about the study before agreeing with an informed consent form (ICF). The total participation time for each survey was between 30 and 45 min and participants were rewarded with 3500 points to exchange for vouchers or gifts at the reward partner network of the company hosting the survey (Toluna Group Ltd).

Measurements

Three draft scales each for the PRI-P and PRI-G were evaluated: Perceived Health Risk to Self (31 items), Perceived Health Risk to Others (3 items), and Perceived Addiction Risk (11 items). A 5-point response scale was used, with ratings ranging from 1 (no risk) to 5 (very high risk), additionally offering a “don’t know” option.

Tobacco use history was captured by the Smoking Questionnaire [34], addressing current and past use of tobacco-related products. Age, sex, education, income, and ethnicity were also captured (see Table 1).

In Survey 2, additional measures were administered for convergent validity assessment: (1) overall measures of the relative perceived risks associated to the five objects (i.e., CC, THS 2.2, E-cigarettes, NRTs, Cessation), based on two 100 mm visual analogue scales (VAS); one for overall health risk to self and one for overall addiction risk [16, 18]; and (2) five items addressing the participant’s perceived short and long-term consequences of smoking [35].

Data analysis

Survey 1 analyses aimed at identifying the items with the best psychometric properties. Perceived Health Risk to Self (31 items) and Perceived Health Risk to Others (3 items) were initially combined to explore the potential of forming one inclusive 34-item scale. The internal construct validity of the items was assessed by Rasch measurement theory (RMT) analysis, which examined: response scale ordering (presence of disordered thresholds which are indicative of inconsistent use of response options); scale targeting (percentage of coverage item threshold distribution), model fit (item and person fit statistics); local dependence (item residual correlations); reliability (person separation index); and differential item functioning (DIF) assessed by age, sex, education, smoking status as well as across different tobacco and nicotine-containing products, and across the application of the scales to personal risk and risk in general (see Table 2 for more details on the definitions and acceptability criteria for RMT analysis).

The application of the Rasch model was motivated by its useful properties such as parameter separation and raw score sufficiency [36]. Parameter separation ensures invariance as a consequence of specific objectivity [12] in the Rasch model. Specific objectivity means that item characteristics do not depend on the respondents who are instrumental in their estimation, and vice versa, respondent characteristics are independent of the items used in their estimation. Hence, comparisons of items, and respondents, are invariant [37]. In other words, the instrument works in the same way for all individuals [38]. Raw score sufficiency proves beneficial from a practical point of view as it permits a simple raw-score-to-measure conversion. At this stage, the unrestricted polytomous Rasch model, also known as the partial credit model, was used [37].

Classical test theory (CTT) analyses were conducted on the item-reduced scales resulting from RMT analyses, including: assessment of data quality (proportion of missing data as an indication of a lack of acceptability); scaling assumptions (similarity of item means and variances, item-total correlations); scale-to-sample targeting (floor and ceiling effects, skewness of item scores); and internal consistency reliability (Cronbach’s alpha) (see Table 3 for more details on the definitions and acceptability criteria for CTT analysis).

Survey 2 analyses replicated the same analyses on the item-reduced scales obtained from Survey 1 for cross-validation with an independent sample. In addition, construct validity (i.e., convergent and known-group) was evaluated. Convergent validity was assessed by non-parametric correlations with individual items of related measures (i.e., VAS on overall health risk; VAS on addiction risk and the five items on short and long-term consequences of smoking). PRI score differences between respondent groups that were expected to differ based on subject matter considerations (known-group validity) were assessed with t-tests. The group differences examined were: (1) perceived personal versus general risk among current smokers (with perceived personal risk expected to be lower) [39, 40]; (2) current versus never smokers (with perceived risk of smoking expected to be lower for current smokers) [40]; and (3) between smokers with versus without intention to quit (with perceived risk of smoking in smokers intending to quit expected to be higher) [41].

To explore the extent to which the PRI scores were influenced by the position of the assessment object in the sequence, mean scores were calculated by object, sequence and smoking group for all PRI scales, based on RMT logit measures transformed into a 0–100 score. Since the number of sequences was very large (120 possible sequences), the assessment of sequence effects was based on pairwise comparisons of objects using t-tests for independent samples [42].

RMT analyses were performed using RUMM2030 and all other analyses were performed with SPSS (version 21). All statistical tests were conducted at a test-wise alpha level of 5%.

Results

Participants

The baseline characteristics of the 2020 and 1640 participants who completed Survey 1 and Survey 2, respectively, are summarized in Table 1. Due to the quota sampling, similar numbers of males and females completed the surveys (46% and 48% of males respectively). Between 61% and 65% of the participants had a high school or higher education and slightly more participants completed Survey 1 in the 46+ years of age group (41% and 36%, respectively). In both surveys, most participants categorized themselves as Caucasians (81% and 80%, respectively). Disposition of participants in Survey 1 and 2 is presented in Table 4.

Scale formation and item reduction (Survey 1)

The 34 items assessing Perceived Health Risk demonstrated no disordered thresholds, reasonable coverage of the item thresholds (88%) and good reliability as assessed by the PSI of 0.97 (Table 5). Through a series of three iterations, a total of 16 items were removed from the initial item pool. Although the psychometric red flags were misfit (n = 9), and uniform DIF (n = 7), the totality of evidence to support the extent to which scales were fit for purpose (i.e., conceptual clarity, contexts of use, intended application and use cross cultural studies) was leveraged in each instance to make the final decisions in relation to item retention. A re-analysis of the reduced 18-item Perceived Health Risk scale (for items see Table 6) revealed that the scale performed appropriately (i.e., no disordered threshold, no DIF for any of the subgroups tested, coverage of 84% of participants, and a PSI of 0.97; Table 5).

Psychometric performance based on CTT methods was also strong: skewness of 0.05; Cronbach’s alpha of 0.99; and corrected Item-Total Correlations ranging from 0.89 to 0.93 (Table 7). The percentage of missing data was 0.1% at most at the item-level, demonstrating high acceptability of the PRI. The proportion of “don’t know” responses was between 11% and 15%. While “don’t know” responses were valuable qualitative information, they had to be treated as missing data in the psychometric analysis. However, the observed proportion of “don’t know” responses had no adverse consequences for parameter estimation and scale evaluation, given the large number of responses in total.

The 11 items assessing Perceived Addiction Risk showed no disordered item thresholds, reasonable coverage of the item thresholds (80%) and good reliability with a PSI of 0.94 (Table 5). Three items showed misfit and one item uniform DIF. Once again, we leveraged all the available evidence to decide on item retention. A re-analysis of the reduced 7-item Perceived Addiction Risk scale (for items see Table 6) revealed that the scale performed appropriately (Table 5). Among the seven items, three are applicable for all objects but for Cessation. One item (feeling anxiety when in a situation where people smoke) was retained for administration only for Cessation (4-item scale for Cessation and 6-item scale for all other tobacco and nicotine-containing products). A re-analysis of the reduced 7-item Perceived Addiction Risk scale revealed that the scale performed appropriately: No disordered thresholds, no DIF for any of the subgroups tested, coverage of 75% and a PSI of 0.93 (Table 5). Psychometric performance based on CTT methods was also strong: Skewness of − 0.41; Cronbach’s alpha of 0.98; Corrected Item-Total Correlations ranging from 0.90 to 0.93 (Table 7). The item-level missing data percentages were at 0.1% at most. At the item level, the proportion of “don’t know” responses was between 8% and 12%.

For both the Perceived Health and Addiction Risk scales, the personal versus general risk versions performed equivalently from a psychometric point of view (i.e., no DIF).

Psychometric cross-validation (Survey 2)

The analysis of the Survey 2 18-item Perceived Health Risk scale data revealed that the scale performed appropriately: no disordered thresholds; no DIF; 87% of coverage of participants; and a PSI of 0.97 (see Table 5 for summary statistics and Table 6 for item statistics). Psychometric performance based on CTT methods was also strong: skewness 0.02; Cronbach’s alpha of 0.99; and Corrected Item-Total Correlations ranging from 0.88 to 0.92 (Table 7).

At the item-level, the percentage of missing data was 0.1% at most, confirming very high acceptability of the PRI. Among completers, 99% of the study participants provided responses to all items, including the “don’t know” option, the latter being treated as missing data in the psychometric analysis. At the item level, the proportion of “don’t know” responses was in the range of 12% and 14%. The item thresholds ranged between − 4.5 and + 4.0 providing for a broad area where the scale was effective allowing for precise and interpretable measurement.

The 7-item Perceived Addiction Risk scale showed no disordered item thresholds, reasonable coverage of the category thresholds (78%) and good reliability with a PSI of 0.94 (see Table 5 for summary statistics and Table 6 for item statistics). Psychometric performance based on CTT methods was also strong: Skewness of − 0.32; Cronbach’s alpha of 0.98; Corrected Item-Total Correlations ranging from 0.92 to 0.95 (Table 7). As for the Perceived Health Risk Scale, the item-level missing data percentages were at 0.1% at most. At the item level, the proportion of “don’t know” responses was between 8% and 13%. The item thresholds of the Perceived Addiction Risk scale ranged between − 5.4 and + 5.3 providing for a broad area where the scale was effective allowing for precise and interpretable measurement.

Construct validity (Survey 2)

For the assessment objects CC, THS 2.2, E-cigarettes and NRT, all correlations between the VAS scores and PRI measures for both Perceived Health Risk and Perceived Addiction Risk were in the range of 0.52 to 0.68 across both types of risk (i.e., personal and general; Table 8). Assuming a reliability of the VAS of 0.6 and applying the Spearman Brown formula [43] for disattenuation imply correlations in the order of 0.68 and 0.89.

Correlations of the 18-item Perceived Health Risk measure with all five items on short- and long-term consequences of smoking were all in the expected direction for both personal and general risk (Table 9). Correlations were mostly weak to moderate, regardless of smoking status and type of risk, with absolute values ranging from 0.10 to 0.40 for personal risk and from 0.20 to 0.46 for general risk. The size of these correlations was not expected to be very high given the specific content of the individual items of the short- and long-term consequences of smoking questionnaire. Importantly, correlations were of similar magnitude across items focusing on short-term (first three items) or long-term consequences of smoking CC (last two items). This provides strong evidence that the 18-item Perceived Health Risk scale is balanced in terms of short- and long-term risks.

Descriptive statistics of the PRI scales by object (Table 10) showed that the perceived risk of CC was always the highest for both Perceived Health Risk and for Perceived Addiction Risk. This was true for personal and general risk. The risk of THS 2.2 was uniformly considered second-highest after CC. E-Cigarettes were perceived to be less risky compared to THS 2.2. The perceived risks of NRT and Cessation generally marked the lower end. Since the risks associated with NRT referred to the risk of using NRT for a certain period of time in the future, while Cessation meant the perception of incurred risks of smoking CC in the past, this could explain that NRT was perceived as more risky than Cessation. It might seem obvious to compare the levels of observed perceived risk with actual objective risk as another way of assessing convergent validity of the PRI. Indeed, the perceived risk of ongoing use of CC was clearly higher than Cessation or using NRT, which was in line with what one would have expected. However, the evaluation of objective risk of E-cigarettes is still a matter of ongoing research and no final assessment has been made yet. Even less is known about the objective risk of THS 2.2. Thus, the potential to compare perceived risks and objective risk is limited. In fact, the lack of objective evidence of risks associated with using THS 2.2 was one of the main reasons to develop the PRI.

With respects to known-group validity, all mean differences were in the expected direction. In terms of the effect sizes (Cohen’s d), differences between smokers and never smokers were more pronounced than differences between personal and general risk among current smokers (Table 11). Regarding the differences between current smokers with and without intention to quit, known-group validity was confirmed as well by the perceived risk being higher for smokers with quitting intention.

Carry-over effects (Survey 2)

For the assessment objects CC, THS 2.2 and E-cigarettes no differences were detected between measures of Perceived Health Risk when the product was presented first versus second or later (Table 12). However, for Cessation, both personal and general Perceived Health Risk were higher when Cessation was presented as the first assessment object compared to it being presented after any other assessment. For NRT, a similar effect was found for perceived general risk, with the level of perceived risk being higher when NRT was assessed first.

Discussion

The psychometric performance of the PRI was strong across both RMT and CTT analyses, supporting the conclusion that the 18-item Perceived Health Risk scale and the 7-item Perceived Addiction Risk scale are reliable and psychometrically valid. Construct validity evaluations of both scales met expectations through inter-scale correlations and findings from known-group comparisons. At the same time, the assessment of convergent validity was limited due to the absence of an undisputed gold standard measure for perceived risk assessment. Specifically, no definitive assessment of objective risks of products, such as E-Cigarettes or THS 2.2, has been made that would allow to compare objective and perceived risks. The PRI scale measures were correlated with single items (VAS or items from the short- and long-term consequences of smoking questionnaire), resulting overall in moderate convergent validity, mostly due to the lack of reliability of single items compared to PRI scale measures.

To enable appropriate use of the PRI, the final outcome of the present study was the development of a calibrated scoring table (available through MAPI Research Trust), based on weighted likelihood estimation (WLE) [44]. Given the participant raw scores and item parameters, the calibration was done with the restricted Rasch model for polytomous responses [45, 46]. For complete data, the resulting conversion table transfers sum scores to logit measures, which are mapped to a 0–100 scale for convenience. The conversion is a simple linear transformation that changes the logit mean of 0 to 50 and converts the most extreme measures to 0 and 100, respectively.

The application of the Rasch model for measurement [45, 46] implied that item discrimination was supposed to be the same across all items in a scale. While this property of the model provides for invariance in the parameters of the model as an advantageous property facilitating generalizability, it undoubtedly represents a restriction to the data. More general item response theory (IRT) models, such as the Generalized Partial Credit model [47], account for different item discrimination by estimating additional parameters. However, in the case of the PRI, the assumption of equal discrimination was empirically supported. Therefore, estimating discrimination parameters would have run contrary to the general scientific principle of parsimony and would not have significantly improved the fit of the model to the data.

The relatively high item-intercorrelations (between 0.75 and 0.89 for Perceived Health Risk in Survey 2; Table 7) could be of concern as a potential indication of item redundancy. However, no specific pair of items stood out with respect to the item-intercorrelation. Rather, the high correlations were a result of consistency in the response patterns and high measurement precision. What is more, redundancy was a key criterion in the data analysis by examining residual correlations. In the item reduction phase, any potential duplication of content was thoroughly considered ensuring that the final scales lack any redundancy.

There are four key strengths in this instrument development program. First, the content validity of the new instrument (that is the scale scores represent the concepts of interest, and the instructions and item content are appropriate, comprehensive and understandable to the target population) was evidenced by information gathered from literature review, focus groups, expert opinions, cognitive debriefing interviews, and pilot field testing.

Second, the design of the quantitative studies included a broad range of subpopulations in the US in terms of smoking status, considering current and past smoking behaviour as well as intentions to quit smoking cigarettes. The diversity of subpopulations provided a broad frame of reference for which the validity of the PRI could be demonstrated. In addition, the sample design provided an approximately equal representation of all four smoking status groups, ensuring adequate psychometric analysis for all groups. Within each smoking status group, additional stratification allowed for the assessment of measurement equivalence across age groups, sex and levels of education. The psychometric cross-validation with an independent sample and the large total sample size support a robust psychometric quality of the items.

Third, the fit of the data to the unidimensional measurement model and the lack of DIF by assessment object demonstrate that the items for each scale worked as a set, representing manifestations of unidimensional perceived health and addiction risks, respectively, for a diversity of products, i.e., combustible cigarettes, heat-not-burn product, e-cigarettes, nicotine replacement therapy products as well as Cessation. Therefore, the instrument development provides a solid foundation for the scales to be used with other products (e.g., different potential RRPs). Nevertheless, for application of the PRI to products substantially different to those assessed here, such as smokeless tobacco, reinvestigating the validity of the scales is advisable. In particular, the comparability of the perceived risk measures with those related to products considered in the scale development project should be assessed at the item level by DIF analyses.

Fourth, the instrument development accounted for two types of risk perceptions: personal risk (risk to the individual respondent) and general risk (risk to users of the products in general). Both personal (PRI-P) and general (PRI-G) versions of the instrument performed equally well from a psychometric point of view, implying that either of the two could be used in future studies, depending on the design and objective.

There are also some limitations to our study. First, web panels are not fully representative of the US population. In particular, a bias towards higher education is a typical and widespread phenomenon in panel-based online surveys [48]. In order to mitigate this limitation, education was included as a sampling quota. The relative simplicity of the items, their high comprehensibility as demonstrated in the CDIs and the very low rates of non-completers dropping out of the survey prematurely suggest the suitability of the PRI for a broad range of educational levels. This conclusion was also supported by evidence from the psychometric analyses, with DIF analyses confirming that the scales work equivalently for participants with higher and lower education.

Second, as the study was administered as a web survey, all psychometric findings are in principle confined to this mode of administration. As a suggestion for future research, the administration of the PRI as a paper-and-pencil questionnaire or as a telephone interview should involve a cross-method comparison of the psychometric properties. The likelihood of the validity of the PRI to be maintained when administered in modes other than online, particularly through paper-and-pencil, is deemed high, as the instruments proved very stable in terms of diverse subpopulations (e.g., based on smoking status) and objects (products, behaviours). The simplicity of the items themselves also contributes to high comprehensibility of the PRI, as demonstrated in the qualitative phase (cognitive debriefing interviews), which indeed included the presentation of the instruments on paper.

Third, the assessment of perceived health risks concerning different types of tobacco and nicotine-containing products was not completely free of carry-over effects. In principle, fit of the data to the Rasch model supports specifically objective measurement and, thus, invariance. However, specific objectivity only applies within a frame of reference, for which invariance of comparisons has been empirically demonstrated [49]. The analysis of repeated measurements of perceived risks provided evidence that the study design may jeopardize invariance and, therefore, comparability of measures. The assessment of one type of tobacco and nicotine-containing product may have a priming effect on the subsequent assessment of another product. Studies applying the PRI in a repeated measurement design should thus take the potential of carry-over effects into account, particularly if perceived risks of Cessation and of NRTs are to be assessed. Our findings suggest that these effects may best be accommodated by a fixed order of objects presented to the participants. The best-known product should be presented first, to set a meaningful reference point. Thereafter, tobacco products should be presented by decreasing familiarity. Based on the principle of moving from use of products to their non-use, objects related to quitting smoking should be presented last, with Cessation (not involving any use of NRT) to be presented as the very last object.

Finally, a possible concern when applying the PRI to multiple objects in a repeated measurement design could be response burden. However, the structural simplicity of the PRI consisting of items that are brief statements allows for a straightforward and fast completion (less than 5 min per object). We did consider a shorter 9-item version of the Perceived Health Risk scale. In terms of traditional reliability, the short version would only be slightly less reliable. The standard error of measurement for an individual respondent, though, would increase by up to about 80%, depending on the level of perceived risk. Given the predominant role of perceived health risk from a respondent’s perspective, we therefore recommend the application of the full 18-item scale.

Conclusions

By quantifying perceived tobacco and nicotine-containing product risks, the PRI fills an important methodological gap and may be used in clinical and population-based studies. Based on the structured development process and the amount of validation data, the PRI can be a valuable self-report instrument that provides a scientifically rigorous method to quantify the perceived risks of tobacco and nicotine-containing products and related behaviors. With increasing numbers of researchers incorporating the PRI into their studies, we envision a rapidly expanding knowledge-base, informing further interpretation of risk perception data comparing a large spectrum of tobacco and nicotine products, so that the health and public policy communities can make more informed decisions on the potential public health impact of MRTPs. Such data will provide meaningful information on: (1) the effects of risk perception on tobacco and nicotine-containing product use behavior among current tobacco users; (2) the effects on product use initiation among non-users; and (3) the effects of risk communication on consumer understanding and perception.

Notes

The three experts involved in the literature review have strong expertise in public health and quality of life, consumer risk perception, qualitative and quantitative research in scale development. They currently hold, or previously held, positions at governmental regulatory bodies, universities or contract research organisations.

The four experts involved at this stage were subject matter key opinion leaders (KOLs) in fields of nicotine and other addictions, motivational aspects of consumer perception, in epidemiologic study design, data management, and evaluation, measurement of clinical concepts, evidence-based medicine, and statistical analysis in health. All experts hold leading positions at universities or organisations in health care in the USA or Canada. The KOLs have a long record of publications in the healthcare sector and have contributed to governmental programs at treating various kinds of addictions in public health. None of the four experts was involved in the previous literature review.

Reduced Risk Products (“RRPs”) is the term used by Philip Morris Products S.A. to refer to products with the potential to reduce individual risk and population harm in comparison to smoking cigarettes. More details are available on www.pmiscience.com.

Abbreviations

- CC:

-

Conventional cigarette

- CDI:

-

Cognitive debriefing interview

- CTT:

-

Classical test theory

- DIF:

-

Differential item functioning

- FDA:

-

Food and Drug Administration

- ICF:

-

Informed consent form

- MRTP:

-

Modified risk tobacco product

- NRT:

-

Nicotine replacement therapy

- PRI:

-

Perceived Risk Instrument

- PSI:

-

Person separation index

- RMT:

-

Rasch measurement theory

- RRP:

-

Reduced risk products

- THS 2.2:

-

Tobacco Heating System 2.2

- VAS:

-

Visual analog scale

- WLE:

-

Weighted likelihood estimation

References

U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. The health consequences of smoking - a report of the surgeon General. Atlanta, GA: US Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Office on Smoking and Health; 2004.

U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. The health benefits of smoking cessation. Rockville: US Department of Health and Human Services Public Health Service Centers for Disease Control Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion Office on Smoking and Health; 1990. DHHS Publication No. (CDC)9O-8416

Stratton K, Shetty P, Wallace R, Bondurant S. Clearing the smoke: the science base for tobacco harm reduction-executive summary. Tob Control. 2001;10:189–95.

WHO (World Health Organization). Monograph: advancing knowledge on regulating tobacco products. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2009.

FDA (Food and Drug Administration). Guidance for industry - Modified risk tobacco product applications - Draft Guidance. Silver Springs, Maryland: FDA; 2012.

Hatsukami DK, Biener L, Leischow SJ, Zeller MR. Tobacco and nicotine product testing. Nicotine Tob Res. 2012;14:7–17.

Bandura A. A social cognitive theory of action. In: Forgas JP, Innes JM, Science IUoP, Society AP, editors. Recent advances in social psychology: an international perspective. North-Holland: Elsevier; 1989. p. 127–38.

Ajzen I. The theory of planned behavior. Organ Behav Hum Decis Process. 1991;50:179–211.

Rees VW, Kreslake JM, Cummings KM, O’Connor RJ, Hatsukami DK, Parascandola M, Shields PG, Connolly GN. Assessing consumer responses to potential reduced-exposure tobacco products: a review of tobacco industry and independent research methods. Cancer Epidemiol Biomark Prev. 2009;18:3225–40.

Salzberger T, Chrea C, Cano SJ, Martin M, Atkison M, Emilien G, Mainy N, Ramazzotti A, Weitkunat R, Lüdicke F. Perceived risks associated with the use of tobacco and nicotine-containing products: findings from qualitative research. Tob Sci Technol. 2017;50:32–42.

Rasch G. Probabilistic models for some intelligence and attainment tests. (Expanded edition (1980) with foreword and afterword by B.D. Wright, Chicago, Illinois: The University of Chicago Press). Copenhagen: Danish Institute for Education Research; 1960. Reprinted by MESA Press, 1980

Rasch G. On specific objectivity: an attempt at formalizing the request for generality and validity of scientific statements. Dan Yearb Philos. 1977;14:58–94.

Fisher WP, Stenner AJ. Theory-based metrological traceability in education: a reading measurement network. Measurement. 2016;92:489–96.

Andrich D, Pedler P. On a law of ordinal error. J Phys Conf Ser. 2018;1044:012055.

Rindfleisch A, Crockett DX. Cigarette smoking and perceived risk : a multidimensional investigation. J Public Policy Mark. 1999;18:159–71.

Rodu B, Plurphanswat N, Hughes JR, Fagerstrom K. Associations of proposed relative-risk warning labels for snus with perceptions and behavioral intentions among tobacco users and nonusers. Nicotine Tob Res. 2015;18(5):809–16.

Hamilton WL, Norton G, Ouellette TK, Rhodes WM, Kling R, Connolly GN. Smokers’ responses to advertisements for regular and light cigarettes and potential reduced-exposure tobacco products. Nicotine Tob Res. 2004;6(Suppl 3):S353–62.

Biener L, Bogen K, Connolly G. Impact of corrective health information on consumers’ perceptions of “reduced exposure” tobacco products. Tob Control. 2007;16:306–11.

O’Connor RJ, Hyland A, Giovino GA, Fong GT, Cummings KM. Smoker awareness of and beliefs about supposedly less-harmful tobacco products. Am J Prev Med. 2005;29:85–90.

Shadel WG, Lerman C, Cappella J, Strasser AA, Pinto A, Hornik R. Evaluating smokers’ reactions to advertising for new lower nicotine quest cigarettes. Psychol Addict Behav. 2006;20:80–4.

Park ER, Ostroff JS, Rakowski W, Gareen IF, Diefenbach MA, Feibelmann S, Rigotti NA. Risk perceptions among participants undergoing lung cancer screening: baseline results from the National Lung Screening Trial. Ann Behav Med. 2009;37:268–79.

Linacre JM. Sample size and item calibration stability. Rasch Meas Trans. 1994;7:328–9.

Budd GM, Preston DB. College student’s attidudes and beliefs about the consequences of smoking: development and normative scores of a new scale. J Am Acad Nurse Pract. 2001;13:421–7.

Jeffries SK, Catley D, Okuyemi KS, Nazir N, McCarter KS, Grobe JE, Ahluwalia JS. Use of a brief smoking consequences questionnaire for adults (SCQ-A) in African American smokers. Psychol Addict Behav. 2004;18:74–7.

Gilliard J, Bruchon-Schweitzer M. Development and validation of a multidimensional smoking behaviour questionnaire. Psychol Rep. 2001;89:499–509.

Smith SY, Curbow B, Stillman FA. Harm perception of nicotine products in college freshmen. Nicotine Tob Res. 2007;9:977–82.

O’Connor RJ, McNeill A, Borland R, Hammond D, King B, Boudreau C, Cummings KM. Smokers’ beliefs about the relative safety of other tobacco products: findings from the ITC collaboration. Nicotine Tob Res. 2007;9:1033–42.

IOM (Institute of Medicine). Scientific standards for studies on modified risk tobacco products. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press; 2012.

WHO (World Health Organization). Monitoring tobacco use. In: Guidelines for Controlling and Monitoring the Tobacco Epidemic. Geneva: WHO; 1998. p. 76–101.

Prochaska JO, DiClemente CC. Stages and processes of self-change of smoking: toward an integrative model of change. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1983;51:390–5.

Prochaska JO, Di Clemente CC. Transtheoretical therapy: toward a more integrative model of change. Psychol Psychother Theory Res Pract. 1982;19:276–88.

Wright BD, Stone MH. Best test design. Rasch measurement. Chicago, IL, USA: MESA Press; 1979.

Hobart JC, Cano SJ, Warner TT, Thompson AJ. What sample sizes for reliability and validity studies in neurology? J Neurol. 2012;259:2681–94.

Weitkunat R, Coggins CRE, Sponsiello-Wang Z, Kallischnigg G, Dempsey R. Assessment of cigarette smoking in epidemiologic studies. Beiträge zur Tabakforschung Int. 2013;25:638–48.

Slovic P. What does it mean to know a cumulative risk? Adolescents’ perceptions of short-term and long-term consequences of smoking. J Behav Decis Mak. 2000;13:259–66.

Fischer GH, Molenaar IW. Rasch models: foundations, recent developments, and applications. New York: Springer-Verlag; 1995.

Andrich D. Rasch models for measurement. Beverly Hills: Sage Publications; 1988.

Hagquist C, Bruce M, Gustavsson JP. Using the Rasch model in nursing research: an introduction and illustrative example. Int J Nurs Stud. 2009;46:380–93.

Weinstein ND. Accuracy of smokers’ risk perception. Nicotine Tob Res. 1999;1(Suppl 1):S123–30.

Weinstein ND, Marcus SE, Moser RP. Smokers’ unrealistic optimism about their risk. Tob Control. 2005;14:55–9.

Borland R, Yong HH, Balmford J, Fong GT, Zanna MP, Hastings G. Do risk-minimizing beliefs about smoking inhibit quitting? Findings from the international tobacco control (ITC) four-country survey. Prev Med. 2009;49:219–23.

Wellek S, Blettner M. On the proper use of the crossover design in clinical trials: part 18 of a series on evaluation of scientific publications. Dtsch Arztebl Int. 2012;109:276–81.

Spearman C. The proof and measurement of association between two things. Int J Epidemiol. 1904;39:1137–50.

Warm TA. Weighted likelihood estimation of ability in item response theory. Psychometrika. 1989;54:427–50.

Andrich D. A rating formulation for ordered response categories. Psychometrika. 1978;43:561–73.

Andrich D. A general form of Rasch’s extended logistic model for partial credit scoring. Appl Meas Educ. 1988;1:363–78.

Muraki E. A generalized partial credit model. In: van der Linden WJ, Hambleton RK, editors. Handbook of modern item response theory. New York, NY: Springer New York; 1997. p. 153–64.

Schonlau M, van Soest A, Kapteyn A, Couper M. Selection bias in web surveys and the use of propensity scores. Sociol Methods Res. 2009;37:291–318.

Salzberger T. Reporting a Rasch analysis. In: Christensen KB, Kreiner S, Mesbah M, editors. Rasch Models in Health. NJ: iSTE London - Wiley Hoboken; 2013. p. 347–61.

Wright BD, Masters GN. Rating Scale Analysis: Pluribus Press; 1982.

Andrich D, de Jong JHAL, Sheridan BE. Diagnostic opportunities with the Rasch model for ordered response categories. In: Rost J, Langeheine R, editors. Applications of latent trait and latent class models in the social sciences. New York: Waxmann Publishing Co.; 1997. p. 59–70.

Yen WM. Effects of Local Item Dependence on the Fit and Equating Performance of the Three-Parameter Logistic Model. Applied Psychological Measurement. 1984;8:125–45.

Christensen KB, Makransky G, Horton M. Critical Values for Yen’s Q3: Identification of Local Dependence in the Rasch Model Using Residual Correlations. Applied Psychological Measurement. 2017;41:178–94.

Marais I. Local dependence. In: Rasch models in health Edited by Christensen KB, Kreiner S, Mesbah M. London, UK: Wiley-ISTE Ltd.; 2013. p. 111–30.

Andrich D. An elaboration of Guttman scaling with Rasch models for measurement. Sociological Methodology. 1985;15:33–80.

Andrich D. An index of person separation in latent trait theory, the traditional KR-20 index, and the Guttman scale response pattern. Edu Res Pers. 1982;9(1):95–104.

Andrich D, Hagquist C. Real and artificial differential item functioning. Journal of Educational and Behavioral Statistics. 2012.

WHOQOL Group. The World Health Organistion Quality of Life Assessment (WHOQOL): Development and general psychometric properties. Social science & medicine. 1998;46:1569–85.

Hays RD, Hayashi T. Beyond internal consistency reliability: rationale and user’s guide for Multitrait Analysis Program on the microcomputer. Behavior Research Methods, Instruments, & Computers. 1990;22:167–75.

DeVellis RF. Scale development: theory and applications. USA: Sage Publications; 2003.

Likert R. A technique for the measurement of attitudes. Archives of Psychology. 1932;140:5–53.

McHorney CA, Ware JEJ, Lu JF, Sherbourne CD. The MOS 36-item Short-Form Health Survey (SF-36): III. Tests of data quality, scaling assumptions, and reliability across diverse patient groups. Medical Care. 1994;32:40–66.

Guttman L. Some necessary conditions for common-factor analysis. Psychometrika. 1954;19:149–61.

Ware JE, Harris WJ, Gandek B, Rogers BW, Reese PR. MAP-R for Windows: Multitrait / multi-item analysis program-revised users' guide version 1. Boston MA: Health Assessment Lab; 1997.

McHorney CA, Ware JE, Raczek AE. The MOS 36-Item Short-Form Health Survey (SF-36): II. Psychometric and clinical tests of validity in measuring physical and mental health constructs. Med Care. 1993;31:247–63.

Hays RD, Anderson R, Revicki D. Psychometric considerations in evaluating health-related quality of life measures. Qual Life Res. 1993;2:441–9.

Cronbach LJ. Coefficient alpha and the internal structure of tests. Psychometrika. 1951;16:297–334.

Acknowledgements

We wish to thank Louis A. Morris at Louis A. Morris & Associates Inc., Steve Roulet and Pierpaolo Magnani at Philip Morris International Management S.A. for their input they provided during the development of the PRI.

Funding

This research was funded by Philip Morris Products S.A. However, the funders were not involved in the psychometric data analysis and interpretation.

Availability of data and materials

Please contact authors for data requests.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

SC and TS conducted and interpreted the data analysis, and wrote the manuscript. Authors CC, GE, and NM were involved in the conception and design of the studies. TA was the principal investigator for all fieldwork reported in the manuscript. AR, FL, and RW were involved in providing additional input and guidance on the study design and reviewing drafts of this manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Survey 1 (administered between February and March 2014) and Survey 2 (administered between May and June 2014) were both approved by the New England Institutional Review Board (reference numbers NEIRB# 13–431 and IRB# 14–211) and the participants received complete information about the study before agreeing with an informed consent form (ICF).

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

Authors #2, #5, #6, #7, #8, and #9 are employees from Philip Morris Products S.A. and AR from Philip Morris International Management S.A. Author #4 was an employee of Covance Market Access Inc. which was contracted and paid by Philip Morris International to perform all the studies reported in this article. Authors #1 and #3 are contracted and paid by Philip Morris International.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Cano, S., Chrea, C., Salzberger, T. et al. Development and validation of a new instrument to measure perceived risks associated with the use of tobacco and nicotine-containing products. Health Qual Life Outcomes 16, 192 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12955-018-0997-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12955-018-0997-5