Abstract

Background

The purpose of this study was to define the potency of amikacin and comparator agents against a collection of blood and respiratory nosocomial isolates implicated in ICU based pulmonary infections gathered from US hospitals.

Methods

Minimum inhibitory concentrations of amikacin, aztreonam, cefepime, ceftazidime, ceftolozane/tazobactam, ceftriaxone, ciprofloxacin, imipenem, meropenem, piperacillin/tazobactam and tobramycin were tested against 2460 Gram-negative isolates. Amikacin had 96 % susceptibility against the combined E. coli and K. pneumoniae isolates and 95 % susceptibility against P. aeruginosa.

Results

Ninety-six percent of all of isolates tested were susceptible (i.e., MICs ≤16 mg/L) to amikacin by current laboratory standards which demonstrates a high level of activity to combat infections caused by these organisms including ESBL, MDR, β-lactam and fluoroquinolone resistant strains. Moreover, 99 % of all organisms had amikacin MICs ≤64 mg/L.

Conclusions

Overall, these data highlight the continued potency of amikacin and suggest that the achievable lung concentrations of approximately 5000 mg/L with the administration of the amikacin by inhalation (Amikacin Inhale, BAY41-6551) will exceed the MICs typically observed for P. aeruginosa, E. coli and K. pneumoniae in the hospital setting.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

The management of hospital-acquired pneumonia (HAP) and ventilator-associated pneumonia (VAP) has been made increasingly difficult due to the emergence of resistance and the potential for reduced antibiotic lung penetration in the intubated patient. HAP continues to be the second most common cause of nosocomial infections in the United States and is associated with increases in hospital length of stay, healthcare costs and represents a major cause of mortality especially in critically ill patients [1, 2]. VAP, a subset of HAP, that occurs in mechanically ventilated patients more than 48 h after tracheal intubation and occurs in 9–40 % of mechanically ventilated patient’s making it among the most frequent infections in the ICU [1, 3].

Gram-negative bacteria are responsible for a substantial proportion of HAP and VAP infections. Pseudomonas aeruginosa, along with the Enterobacteriacae, Escherichia coli and Klebsiella pneumoniae are amongst the most common etiological organisms representing approximately two-thirds of causative agents [4, 5]. Nosocomial pneumonia caused by P. aeruginosa, E. coli and K. pneumoniae continues to pose significant challenges in US hospitals due to their prevalence and the acquisition of numerous antimicrobial resistance mechanisms. As a result, the selection of empirical antibiotic therapy in patients with nosocomial respiratory tract infections has become increasingly challenging as the number of potentially effective agents has been reduced due to evolving resistance. Yet more challenging is delivering sufficiently high antibiotic concentrations to the lung as many parenteral therapies have poor or variable penetration. The delivery of antibiotics directly to the site of infection presents a unique clinical opportunity to enhance patient outcomes by achieving high local concentrations that overcome resistance while minimizing the potential for toxicity associated with systemic administration.

Amikacin Inhale (BAY41-6551) is a reformulated solution of amikacin (AMK) combined with a drug-delivery module that is currently under phase III study as an adjunctive therapy for the treatment of Gram-negative pneumonia in intubated and mechanical ventilated patients. In vitro pharmacodynamic models evaluating the achievable epithelial lining fluid (ELF) concentrations after the administration of AMK inhalation against Gram-negative organisms demonstrated rapid and sustainable bactericidal killing of AMK both alone and in combination with systemic exposures of meropenem when AMK MICs were ≤256 mg/L [6]. Our objective was to define the potency and MIC distribution of AMK against a US collection of P. aeruginosa, E. coli, K. pneumoniae nosocomial isolates and relate these data to achievable lung concentrations of the compound when delivered via the aerosol route.

Methods

Fifty US hospitals, 41 teaching and 9 community provided non-duplicate nosocomial blood and respiratory isolates of E. coli, K. pneumoniae and P. aeruginosa from adult inpatients. Additionally, five of these hospitals also provided S. maltophilia respiratory isolates. Organisms were identified at each participating site using the standard methods. The isolates were transferred to trypticase soy agar slants for shipping to the Center for Anti-Infective Research and Development, Hartford Hospital, Hartford, CT, USA. Collection occurred from 2013 into 2014.

Clinical Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI) defined broth microdilution methods were employed to determine minimum inhibitory concentration (MICs) for AMK, aztreonam (ATM), cefepime (FEP), ceftazidime (CAZ), ceftolozane/tazobactam (C/T), ceftriaxone (CRO), ciprofloxacin (CIP), imipenem (IPM), meropenem (MEM), piperacillin/tazobactam (TZP) and tobramycin (TOB) [7]. Antibiotics were purchased from Sigma (St. Louis, MO) except for C/T which was provided by Cubist Pharmaceuticals. Quality control was performed on each batch of MIC testing using E. coli 25922 and P. aeruginosa 27853 as defined by CLSI. All transfer and colony counts were performed on trypticase soy agar plates containing 5 % blood. CLSI and FDA breakpoints were used to define susceptibility. For C/T the FDA breakpoints of 2 mg/L for Enterobacteriaceae and 4 mg/L for P. aeruginosa were utilized [8]. Isolates that were non-susceptible to AMK (i.e., ≥32 mg/L) by current laboratory definitions were repeated and confirmed.

Pseudomonas aeruginosa were identified as multidrug resistant (MDR) if they displayed resistance to 3 or more classes as represented by the following phenotypic resistance profiles: CIP (MIC ≥4 mg/L), IPM (MIC ≥8 mg/L), CAZ (MIC ≥32 mg/L), TZP (MIC ≥128 mg/L) and TOB (MIC ≥16 mg/L) [9].

Escherichia coli and K. pneumoniae were tested for extended spectrum β-lactamases (ESBL) production if they had an MIC of ≥1 to 2 mg/L of the following: ATM, CRO or CAZ. CLSI defined ESBL confirmation studies were then undertaken using additional MIC testing with CAZ, CAZ with clavulanate, cefotaxime and cefotaxime with clavulanate [7].

Isolates testing non-susceptible to ertapenem, imipenem, or meropenem were evaluated for carbapenemase production using the CarbaNP test [10].

Results

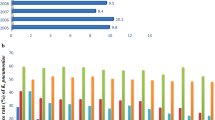

Hospitals provided nosocomial blood (n = 1118) and respiratory isolates (n = 527) of E. coli (n = 811) and K. pneumoniae (n = 835). Demographic from these patients are shown in Table 1. Rank order % susceptibility for the Enterobacteriaceae, was as follows: AMK 96 %, IPM 96 %, MEM 96 %, C/T 94 %, TZP 88 %, FEP 87 %, CAZ 85 %, ATM 85 %, TOB 84 %, CRO 84 % and CIP 74 % (Table 2). For AMK 96 % of these organisms had MICs ≤16 mg/L, 2 % 32 mg/L and 2 % ≥64 mg/L (Fig. 1). Comparing AMK against both FEP (n = 216) and TZP resistant (n = 191) isolates only 2 % of the organisms had MICs ≥128 mg/L, respectively. Interesting one E. coli isolate was found to have an AMK MIC of 65,536 mg/L. Isolates from blood had a slightly higher (1–7 %) susceptibility for all agents tested than the respiratory isolates.

Of the 1646 E. coli and K. pneumoniae collected, 173 isolates were confirmed to be ESBL positive. Of these ESBL isolates, 87 % were found to have MICs ≤16 mg/L to AMK. When considering only the Enterobacteriaceae confirmed ESBL positive isolates the rank order susceptibility of the conventional agents was as follows: MEM 95 %, IPM 94 %, AMK 87 %, C/T 79 %, TZP 62 %, TOB 39 %, FEP 16 %, CIP 16 %, CAZ 14 %, ATM 9 % and CRO 5 %. For AMK 87 % of these organisms had MICs ≤16 mg/L, 9 % 32 mg/L and 2 % ≥64 mg/L. Of the total Enterobacteriaceae isolates collected three E. coli and 37 K. pneumoniae were carbapenemase-producing as defined by the CarbaNP test. The susceptibility of AMK, CIP and TOB for these isolates were 53, 15 and 10 %, respectively. All of the other agents had <9 % susceptibility. For AMK 53 % of these organisms had MICs ≤16 mg/L, 15 % 32 mg/L and 29 % 64 mg/L and 3 % 256 mg/L.

Hospitals provided 814 nosocomial blood and respiratory isolates of P. aeruginosa. Rank order % susceptibility was as follows: AMK 95 %, C/T 95 %, TOB 90 %, CAZ 74 %, FEP 73 %, MEM 71 %, CIP 68 %, ATM 67 %, TZP 67 % and IPM 62 % (Table 3). For AMK 95 % of these organisms had MICs ≤16 mg/L, 2 % 32 mg/L, 2 % 64 mg/L and 1 % ≥128 mg/L (Fig. 1). Comparing AMK against MEM resistant isolates (n = 236), 91 % of these organisms had MICs ≤16 mg/L, 6 % 32–64 mg/L and 3 % ≥128 mg/L. Comparing AMK against FEP resistant isolates (n = 222), 89 % of these organisms had MICs ≤16 mg/L, 9 % 32–64 mg/L and 2 % ≥128 mg/L. Comparing AMK against TZP resistant isolates (n = 267), 91 % of these organisms had MICs ≤16 mg/L, 7 % 32–64 mg/L and 1 % ≥128 mg/L. Like the Enterobacteriaceae, P. aeruginosa isolates from blood had a higher (3–14) % susceptibility for all agents tested than the respiratory isolates. The susceptibility profile of ATM, FEP, CAZ, IPM, MEM and TZP was 10 to 14 % higher from patients with blood cultures.

Fourteen percent (n = 116) of the P. aeruginosa population was defined as MDR. In this subset of MDR isolates, rank order %S was as follows: AMK 87 %, C/T 78 %, TOB 52 %, ATM 19 %, MEM 17 %, CAZ 16 %, FEP 13 %, IPM 11 %, CIP 11 % and TZP 6 %. While the MIC90 was 32 for AMK, 23 % of these organisms had MICs ≤4 mg/L, 38 % 8 mg/L, 26 % 16 mg/L 5 % 32 mg/L, 4 % 64 mg/L, 3 % 256 mg/L and 1 % ≥512 mg/L. Of note 2 P. aeruginosa isolates were found to have an AMK MIC of 65,536 mg/L.

The AMK distribution for S. maltophilia (n = 45) was 29 % of these organisms had MICs ≤16 mg/L, 16 % 32 mg/L, 9 % 64, 24 % 128 mg/L, 15 % 256 mg/L and 7 % ≥512 mg/L.

To determine if the susceptibility of these organisms are influenced by the source of infection and location of the patient, we evaluated the % susceptibility of ICU versus Non-ICU patients. The Enterobacteriaceae had no more than a 2 % difference in % susceptibility between the ICU (n = 539) and Non-ICU (n = 1106) patients. For the P. aeruginosa, we noted differing susceptibility profiles derived from the ICU and non-ICU setting. The susceptibility profile of ATM, FEP, CAZ, IPM, MEM and TZP was 5–11 % lower from patients in the ICU. In contrast, ≤3 % difference in was observed between the potency of ICU and non-ICU P. aeruginosa for AMK, C/T, CIP and TOB.

Discussion

Hospital-acquired pneumonia (HAP) and ventilator-associated pneumonia (VAP) are among the most frequent nosocomial infections encountered in the ICU and are responsible for increases in length of stay, mortality and morbidity in critically ill patients. P. aeruginosa, along with the Enterobacteriacae, E. coli and K. pneumonia represent a substantial proportion of HAP and VAP infections. The use of empirical broad spectrum antibiotics for the treatment of pneumonia has led to an increase in antimicrobial resistance along with the development of multidrug resistant Gram-negative organisms.

Appropriate antibiotic exposure at the site of infection is an important component for therapy to be clinically effective. Epithelial lining fluid (ELF) is considered to be the site of infection for pneumonia and achieving sufficiently high drug concentrations in ELF are critical for treating pneumonia. The rationale for inhaling antibiotics is to maximize drug delivery to the target site of infection (ELF in the case of pneumonia) and limit the potential for systemic side effects. The uses of inhaled antimicrobials have a long history in the treatment of lower respiratory tract infections specifically in patients with cystic fibrosis [11]. Due to the increasing prevalence of resistant Gram-negative organisms in VAP causing difficult to treat pneumonia along with the limited lung concentrations that can be achieved with standard parentally given antibiotics there has been an increased interest in the use of inhaled antimicrobials such as inhaled amikacin for respiratory tract infections such as in HAP and VAP [12]. In a recently published study, So et al. [6] investigated the in vitro pharmacodynamics of human simulated ELF concentrations of inhaled amikacin against variety of phenotypically diverse susceptible and non-susceptible K. pneumoniae and P. aeruginosa isolates and showed rapid bactericidal activity against isolates with an amikacin MICs of ≤256 mg/L.

The high overall susceptibility profile of amikacin against these Gram-negative organisms of interest in our current study appears to represent the sustained in vitro potency of the compound when compared to two previously reported surveillance programs [13, 14]. The INFORM study collected 7062 clinical P. aeruginosa isolates from Europe, Asia/South Pacific, Latin America and Middle East/Africa [13]. Similar to our data the INFORM global surveillance program found amikacin to have a high susceptibility (89.4 %) against the P. aeruginosa isolates tested. Moreover, the authors also reported similar (±6 %) susceptibility profiles for ceftazidime, cefepime, piperacillin-tazobactam and meropenem to that in our current study.

The SMART surveillance program collected intra-abdominal isolates of E. coli, K. pneumoniae, K. oxytoca and P. mirabilis [14]. E. coli (n = 434) maintained high susceptibilities to amikacin of >99 %, while K. pneumoniae (n = 231) had 93.5 %. Both organisms had ≥92 % susceptibility to imipenem and ertapenem. In the SMART program amikacin retained the highest susceptibility to MDR Enterobacteriaceae of all the agents tested.

Conclusions

In this study we defined the phenotypic profile of amikacin against 2460 blood and respiratory nosocomial isolates implicated in ICU based pulmonary infections collected from 50 US hospitals. AMK demonstrated a high level of activity to combat infections caused by the Enterobacteriacae, E. coli and K. pneumoniae including those strains producing ESBLs. When considering E. coli and K. pneumoniae our study found amikacin to have an MIC50 and MIC90 of 4 and 16 mg/L, respectively. Moreover, 96 % of organisms had a MIC of ≤16 mg/L and nearly all (99 %) organisms had MICs ≤64 mg/L despite concomitant β-lactam or fluoroquinolone resistance. In a study conducted by Sader et al. [15] analyzing the in vitro activity of amikacin against isolates gathered from patients hospitalized with pneumonia including VAP, across 62 US hospitals, the MIC50 and MIC90 was reported to be 1 and 32 mg/L, respectively, against K. pneumoniae. In a study investigating E. coli isolates across 66 Canadian medical centers the reported amikacin MIC50 and MIC90 were ≤2 and 4 mg/L, respectively [16].

For P. aeruginosa, our study found amikacin to have an MIC50 and MIC90 of 8 and 16 mg/L, respectively. Against these isolates 95 % of organisms had amikacin MICs of ≤16 mg/L, moreover nearly all (97 %) organisms have MICs ≤32 mg/L. Similarly when compared to the Sader et al. [15] study, P. aeruginosa isolates from 62 US hospitals, amikacin was reported to have an MIC50 and MIC90 of 4 and 8 mg/L, respectively. Another study analyzing similar data from 127 isolates from Canadian hospitals, reported MIC50 and MIC90 of 4 and 16 mg/L, respectively [17].

With respect to resistant Gram-negative bacteria, our study demonstrated that amikacin maintained potent activity against P. aeruginosa MDR organisms. In regards to ESBLs this study showed that AMK was a potent antimicrobial with a high level of activity against these MDR isolates as 87 % had an MIC of ≤16 mg/L. Against MDR P. aeruginosa isolates, amikacin was the most potent antibiotic tested as 87 % of resistant isolates were considered susceptible (i.e., MIC of ≤16 mg/L).

The current surveillance study which incorporated a large number of US hospitals demonstrated the high potency of amikacin against contemporary isolates of E. coli, K. pneumoniae, P. aeruginosa originating from a blood or respiratory source. Moreover, despite resistance to representative agents from the β-lactam and fluoroquinolone classes, AMK maintained high susceptibility for all organisms. As a result of low MIC’s and high achievable lung concentrations of approximately 5000 mg/L, Amikacin Inhale has a potential adjunctive role in the management of bronchopulmonary infections caused by P. aeruginosa, E. coli and K. pneumoniae in the intubated patient. While Amikacin Inhale appears to be a viable adjunctive therapy, patients should also receive appropriate systemic antimicrobial therapy based on local susceptibilities or when available the susceptibility profile of the patient specific isolate(s).

Abbreviations

- HAP:

-

hospital-acquired pneumonia

- VAP:

-

ventilator-associated pneumonia

- ICU:

-

intensive care unit

- P. aeruginosa :

-

Pseudomonas aeruginosa,

- E. coli :

-

Escherichia coil

- K. pneumoniae :

-

Klebsiella pneumoniae

- CT:

-

Connecticut

- US:

-

United States

- AMK:

-

amikacin

- ELF:

-

epithelial lining fluid

- S. maltophilia :

-

Stenotrophomonas maltophilia

- CLSI:

-

Clinical Laboratory Standards Institute

- MICs:

-

minimum inhibitory concentration

- ATM:

-

aztreonam

- FEP:

-

cefepime

- CAZ:

-

ceftazidime

- C/T:

-

ceftolozane/tazobactam

- CRO:

-

ceftriaxone

- CIP:

-

ciprofloxacin

- IPM:

-

imipenem

- MEM:

-

meropenem

- TZP:

-

piperacillin/tazobactam

- TOB:

-

tobramycin

- MO:

-

Missouri

- FDA:

-

food and drug administration

- MDR:

-

multidrug resistant

- ESBL:

-

extended spectrum β-lactamases

- K. oxytoca :

-

Klebsiella oxytoca

- P. mirabilis :

-

Proteus mirabilis

References

Pfaller MA, Mendes RE, Sader HS, Jones RN. Telavancin activity against Gram-positive bacteria isolated from respiratory tract specimens of patients with nosocomial pneumonia. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2010;65(11):2396–404.

American Thoracic Society; Infectious Diseases Society of America. Guidelines for the management of adults with hospital-acquired, ventilator-associated and healthcare-associated pneumonia. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2005;171(4):388–416.

Barbier F, Andremont A, Wolff M, Bouadma L. Hospital-acquired pneumonia and ventilator-associated pneumonia: recent advances in epidemiology and management. Curr Opin Pulm Med. 2013;19(3):216–28.

Charles MP, Easow JM, Joseph NM, Ravishankar M, Kumar S, Sivaraman U. Aetiological agents of ventilator-associated pneumonia and its resistance pattern—a threat for treatment. Australasian Med J. 2013;6(9):430–4.

Bayer HealthCare AG. Amikacin inhalation solution and the pulmonary drug delivery system [PDDS Clinical] Gram-negative pneumonia. 2012;08 Nov.

So W, Crandon JL, Hamada Y, Nicolau DP. Antibacterial activity of achievable epithelial lining fluid exposures of Amikacin Inhale with or without meropenem. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2016;2016(71):428–37.

Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute. 2014. Performance standards for antimicrobial susceptibility testing; twenty-fourth informational supplement. CLSI document M100-S24 U. Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute, Wayne, PA.

ZERBAXA (ceftolozane/tazobactam) for injection, for intravenous use. 2014. Initial U.S. Approval: 2014. Cubist Pharmaceuticals.

Bulik CC, Christensen H, Nicolau DP. In vitro potency of CXA-101, a novel cephalosporin, against Pseudomonas aeruginosa displaying various resistance phenotypes, including multidrug resistance. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2010;54(1):557–9.

Dortet L, Poirel L, Nordmann P. Rapid identification of carbapenemase types in Enterobacteriaceae and Pseudomonas spp. by using a biochemical test. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2012;56:6437–40.

Quon BS, Goss CH, Ramsey BW. Inhaled antibiotics for lower airway infections. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2014;11:425–34.

Nicolau DP, Dimopoulos G, Welte T, Luyt CE. Can we improve clinical outcomes in patients with pneumonia treated with antibiotics in the intensive care unit? Expert Rev Respir Med. 2016;3:1–12. doi:10.1080/17476348.2016.1190277.

Nichols WW, de Jonge BL, Kazmierczak KM, Karlowsky JA, Sahm DF. In vitro susceptibility of global surveillance isolates of Pseudomonas aeruginosa to ceftazidime-avibactam: INFORM 2012–2014. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2016. doi:10.1128/AAC.00220-16.

Zalacain M, Biedenbach DJ, Badal RE, Young K, Motyl M, Sahm DF. Pathogen prevalenceand antimicrobial susceptibility among enterobacteriaceae causing hospital-associated intra-abdominal infections in adults in the United States (2012–2013). Clin Ther. 2016. doi:10.1016/j.clinthera.2016.04.035.

Sader HS, Rhomberg PR, Farrell DJ, Jones RN. Arbekacin activity against contemporary clinical bacteria isolated from patients hospitalized with pneumonia. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2015;59(6):3263–70.

Zhanel, George G, et al. Antimicrobial susceptibility of 15,644 pathogens from Canadian hospitals: results of the CANWARD 2007–2009 study. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis. 2011;69:291–306.

Zelenitsky SA, Rubinstein E, Ariano R, et al. Integrating pharmacokinetics, pharmacodynamics and MIC distribution to assess changing antimicrobial activity against clinical isolates of Pseudomonas aeruginosa causing infections in Canadian hospitals (CANWARD). J Antimicrob Chemother. 2013;68(Suppl 1):67–72.

Authors’ contributions

CS and JV were involved in all aspects of this study including data collection, analysis and manuscript preparation. DPN was the principal investigator on this study. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Jennifer Tabor-Renniel, Lucinda Lamb, Sara Robinson, Debora Santini, Kimelyn Greenwood and Elizabeth Cyr for their collective efforts with MIC determination.

Competing interests

David Nicolau has received grants and is on the speakers’ bureau for Bayer Pharma. Christina Sutherland and Jamie Verastegui have no competing interests.

Availability of data and materials

Data will be shared upon request to the corresponding author david.nicolau@hhchealth.org.

Funding

This study was supported by Bayer Pharma AG, Berlin, Germany.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Sutherland, C.A., Verastegui, J.E. & Nicolau, D.P. In vitro potency of amikacin and comparators against E. coli, K. pneumoniae and P. aeruginosa respiratory and blood isolates. Ann Clin Microbiol Antimicrob 15, 39 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12941-016-0155-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12941-016-0155-z