Abstract

Background

Feather damage (FD) resulting from feather pecking remains a concern in non-cage housing systems for laying hens worldwide. This study aimed to identify bird-, housing-, and management-related factors associated with FD in non-cage housing systems as the egg production sector phases out the conventional cage system in Canada. A survey on housing and management practices was developed and distributed to 122 laying hen farms where 39 respondents provided information on non-cage flocks. Farmers visually assessed 50 birds throughout the barn for FD using a 0–2 scoring scale according to severity. Prevalence of FD was calculated as the percentage of birds with any form of FD (score > 0). Multivariable linear regression modeling was used to identify factors associated with FD prevalence.

Results

Six variables were included in the final model and accounted for 64% of the variation in FD between farms. FD prevalence was higher with increasing flock age (0.9% ± 0.29) and when birds were housed in all wire/slatted barns compared with all litter barns (37.6% ± 13.1). Additionally, FD prevalence tended to be higher in barns with manure removal only after depopulation (20.1% ± 10.70). Enrichment also tended to be associated with higher FD (19.1% ± 8.04), possibly indicating that it was provided after FD was observed as a control measure, or, was not efficient in reducing the development of FD.

Conclusions

These findings emphasize the role of litter provision and management (e.g., manure removal effects on air quality), and its potential impact on FD among laying hens in non-cage housing systems in Canada. Further longitudinal and/or intervention studies are needed to assess the potential of the identified factors to function as a management strategy to prevent or reduce FD in non-cage housed laying hens.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Canadian egg production has grown over the past 11 years, with a 4.1% increase from 2016 to 2017 in the sale of table eggs – a trend predicted to continue throughout 2018 due to consumers’ positive outlook on eggs and their associated health benefits [1]. With this growth in egg consumption comes a growing consumer interest in enhanced animal welfare standards and a market for cage-free specialty eggs (e.g., free-run, free-range, organic, and nutrient-enhanced). This interest is demonstrated, for example, by a study in British Columbia in which consumption of specialty eggs rose from a combined 8 to 33% for free-range eggs and 12% for organic eggs over a 2-year period [2]. Canada’s major grocers and other food corporations such as McDonald’s® and Tim Hortons® have also contributed to this shift, pledging to buy only cage-free eggs by 2025 [3].

In light of changing market trends, Canadian egg farming is transitioning away from conventional cage housing of hens and into furnished cage and non-cage systems, such as single-tier floor systems and multi-tier aviaries [4]. Though these housing systems offer birds the space and resources to better perform natural behaviours, they pose welfare risks in other ways, most notably a greater opportunity for feather pecking (FP) behaviour and resulting feather damage (FD). FP is the action by which hens peck or pluck at, and sometimes eat the feathers of their conspecifics, causing FD (feathers that are broken, deformed, or deviate from a smooth and intact state) and feather loss typically on the back/rump, vent, and tail areas [5,6,7]. Loss of feather cover can eventually progress to tissue pecking and mortality due to cannibalism [5].

Feathers are integument features unique to birds and are critical for survival in wild birds. They are smooth, flexible structures largely composed of beta-keratin protein [8]. The various feather types distributed over the body enable birds to carry out locomotive behaviours such as flight or wing-flapping to escape predators and navigate the environment [9, 10], reproductive and social behaviours such as mating displays and shows of aggression through feather raising [8], as well as thermoregulatory behaviours as feathers enable birds to stay warm and dry by providing insulation and a waterproof exterior [11]. In the wild, feathers are kept in good shape with a large portion of the day being dedicated to maintaining their integrity through preening i.e., cleaning, restoring their structure, and applying preen oil [8]. Feathers, much like hair and nails, when damaged cannot repair themselves; thus old feathers get shed through normal preening and replaced through the renewal process of molting [8]. Replacement of feathers can be an immense metabolic stressor, including the replacement of up to 30% of a bird’s body mass [reviewed by [12]] and a basal metabolic rate which can double during molting in avian species [13].

Healthy and functional feather cover is just as important for domestic birds as for wild birds but is much harder to maintain for hens kept in modern housing systems when FP is present. Feather cover damage due to the pecking and pulling out of feathers by other birds represents one of the more common and frustrating challenges in birds kept in intensive production systems [14]. Epidemiological studies in Europe have shown that up to 80% of non-cage flocks exhibit severe FP and FD [15,16,17]. The most well-accepted hypothesis as to the origin of FP is that it is a redirected foraging/feeding behaviour [18] induced by the stress and frustration of living in a barren environment, but it is ultimately multifactorial, including environmental, nutritional, psychological, and genetic factors [19, 20].

Feather loss and FD undoubtedly cause bird discomfort and present a significant welfare issue. In addition to health and well-being implications of poor feather cover, images of birds without feathers do not meet consumer expectations and increase the risk that consumers will lose trust in egg farming and the livestock food system as a whole [21]. Consumers are increasingly interested in food production practices, with a strong relationship between transparency and trust [22]. A 2017 survey indicated that farmers are those held most responsible for demonstrating trust-building transparency in regards to animal well-being [22]. Furthermore, not having a fully feathered flock can affect farmers through poor financial return due to flock health issues or negative consumer perceptions, but also in terms of diminished job satisfaction due to the daily visual impact of compromised bird welfare [23].

Elucidating the contributing factors leading to FD is thus essential for providing good welfare to millions of hens, but also for fostering continued trust between egg farmers and consumers, and consequently, sustainability within the egg farming community. Though numerous epidemiological studies have been conducted in Europe, to the best of the researchers’ knowledge, no large-scale investigations into FD have been done in alternative housing systems in North America. This study was part of a project to investigate FD in the Canadian context where climate, feeding, and management practices can differ considerably from those in Europe and across regions within Canada. Previously, we presented the methodology used to assess FD by farmers [24] as well as research findings of the project in the context of furnished cage systems [25]. In this paper, we present associations between FD and different aspects of management, environment, health, and genetics, which were identified in an effort to provide farmers with strategies to prevent or control FD.

Results

Response rate

Survey packages were distributed to 122 farms with laying hens in alternative housing systems. A total of 64 returned packages were received (52.5% response rate) detailing information for 65 flocks.

General flock information

Thirty-nine of the 65 flocks were housed in non-cage systems (65%), of which 17 flocks were housed in single-tier floor systems (43.6%), and 22 flocks were housed in multi-tier aviary systems (56.4%). A detailed description of study flocks and their management, including their geographic distribution, is provided in van Staaveren et al. [26]. Descriptive statistics for flock size, flock age, and FD prevalence of the non-cage flocks are presented in Table 1. All flocks were beak-treated at day 1 in the hatchery using an infrared laser. With respect to feather colour, 32% of flocks were white-feathered and 68% were brown-feathered. Within the 30 out of 39 flocks that had available breed information, 60.0% were a Lohmann strain, while other strains included Dekalb (6.7%), Hy-line (16.7%), ISA (10.0%), and Novogen (6.7%).

Univariable analysis of factors in non-cage systems

Variables associated at a liberal significance level (α = 0.25), or biologically relevant with FD in non-cage laying flocks at the univariable level of analysis are presented in Table 2. These variables were factors related to farmer characteristics, flock characteristics, housing features, litter management, rearing management, nutrition, and feeding and lighting practices (Table 2).

Linear regression analysis for non-cage systems

Floor type, the frequency of manure removal/manure belt operation, flock age, enrichment provision, matching of rearing and laying environment by providing litter substrate, and provision of a dawn/dusk period were included in the final model and accounted for 64% of the variation in FD between flocks (Table 3). “Age”, “floor type” (with the largest effect contributed by all wire/slatted barns), and “provision of enrichment” were significantly associated with higher FD. Additionally, FD prevalence tended to be higher with decreasing “manure belt frequency” (with the largest effect when manure was removed only at the end of lay). Not matching litter in both rear and lay, as well as not providing a dawn/dusk phase were positively associated with FD however, the associations were not significant (Table 3).

Discussion

Using a nationally distributed questionnaire and the collection of FD scores from sampled flocks, management, environmental, and genetic factors associated with FD outcomes in laying hen flocks housed in non-conventional cage housing systems were assessed. On average, approximately one quarter of the birds within these flocks exhibited some form of FD, either moderate or severe, and factors most strongly associated with FD included increasing flock age, housing with all wire or slatted floors, manure removal only at the end of production, and provision of enrichment material.

The prevalence of FD found among participating flocks was approximately 26% (95% CI: 15.6–36.2%). This is likely an underestimation of the true prevalence of FD typically exhibited on farms in Canada since the surveyed flocks included some that were relatively young or newly brought into lay. Research on FP behaviour and resultant FD has consistently shown that both increase as birds age [27,28,29]. This too is illustrated in the findings of the current study in that a small but positive association between the age of a flock and the level of FD was observed. The flocks surveyed in this study were not uniform in age when scored. While younger flocks may be at risk in terms of FP, they may not have begun to show signs of FD at the time of scoring. Had the study surveyed all flocks at the same age in the middle of the production period, median and mean FD prevalence would have likely been greater in value. Previous epidemiological studies in which laying flocks were scored at the same week of age or within a specific age range past 30 weeks, such as that performed in Sweden by Gunnarsson et al. [30], reported damage on the back area in a median of 62% of birds. In the Netherlands, Bestman and Wagenaar [31] found moderate or severe FD in 71% of birds, and more recently, de Haas et al. [17] found 49% of flocks displayed FD.

The hen integument is damaged in all types of housing systems [32, 33]. Research suggests that FP behaviour is initiated by a small percentage of birds and proceeds to spread throughout a flock [34, 35]. Therefore, housing of large flocks in non-cage systems can contribute to an increased prevalence of FD [36, 37]. In comparison, Decina et al. [25] found a FD prevalence of 21.9% in furnished cages compared to the 25.9% prevalence reported here in non-cage systems, which was not different. When comparing the proportion of birds with FD between flocks in conventional cages, furnished cages, free-run barns, and free-range systems, Sherwin et al. [32] found proportions of birds with FD within each system (24.7, 24.9, 26.9, and 15.5%, respectively). However, while the free-range system had the lowest prevalence, they similarly reported no differences in FD prevalence between the furnished cage and barn system.

Floor type had the largest effect on FD, largely due to the effect of all wire or slatted floors, correlated with an increase in FD of approximately 38% in such flocks. Other epidemiological studies have similarly found associations with absence of litter and increased FP activity or FD, such as an absence of loose litter at the end of lay [38] and restriction to the slatted area during nest box training (severe FP was 24 times more likely) [15]. This profound effect is also in line with the generally accepted notion that FP arises from a lack of foraging substrate [18, 39, 40] and the research demonstrating how chicks and pullets reared without suitable litter material show severe FP and poor plumage later in life [41,42,43].

Low frequency of manure belt running for manure removal was the third factor associated with greater FD. Removal of manure only at the end of the production cycle contributed the most to this effect in that flocks were estimated to exhibit 20% more FD compared to those where manure was cleared more than three times per week. This factor is likely an indicator of air quality, where less frequent manure removal can contribute to increased levels of ammonia in the barn. Concentrations of ammonia tend to be higher in housing systems with manure composting inside the facility compared to systems with regular manure removal, such as manure belts [37]. This has been found in numerous studies when measuring ammonia concentrations in cage systems compared to free-run floor and aviary systems (as reviewed by [44]). Birds find ammonia aversive above concentrations of 20-25 ppm, where it can impair health and reduce immune function [44]. Ammonia at this level is also aversive to barn staff and can compromise their health [45], leading to reduced care and detection of welfare issues within the flock when workers are reluctant to enter the barn. Poor air quality as a general irritant and source of stress plays into the multifactorial nature of FP behaviour, as found by Drake et al. [46] where FD increased with higher carbon dioxide and ammonia in early lay. It is important to note that data was collected in the autumn and early winter months of October to December when ventilation begins to be reduced to conserve warmth in the barn. Decreased ventilation in colder weather paired with humid conditions inside the barn can increase litter moisture and therefore provide a better environment for bacteria to produce ammonia gas [47], a factor which may have influence here.

Removing manure from the barn only at the end of a flock’s cycle can additionally impact air quality in litter systems due to high dust levels when the litter is not changed, and there is poor ventilation of the facility. Dust is contributed by bedding material, feed, dry manure, skin cells, and feathers [48]. Dust and gasses can harm the respiratory system, such as through the loss of cilia needed to clear debris from the upper respiratory tract [49], as well as macro- and microscopic lesions throughout the trachea, lungs, and air sacs [50]. Birds are then predisposed to secondary respiratory diseases caused by bacterial, viral, and fungal infections when the mucosa is compromised [50, 51]. When poor air quality from a multitude of sources leads to negative health outcomes, it contributes to the stress birds experience in these systems and thus increases the risk of FP behaviour and resultant FD.

Lastly, the provision of enrichment in non-cage systems showed a tendency of association with increased FD and was estimated to promote 19% more FD compared to flocks without enrichment. This finding is in opposition to the existing literature – additional foraging opportunities afforded by enrichments such as pecking blocks, hay bales, and hanging objects are viewed as effective methods of FP and FD prevention, especially during rearing [52,53,54]. It is possible here that if birds were reared in a non-enriched environment, provision of these enrichments during the laying period were ineffective at preventing or minimizing FD, as suggested by Glatz [55]; however the questionnaire did not capture information on enrichment during rearing so this issue cannot be further investigated here. Additionally, producers that have regular issues with FP may have been the ones to provide enrichment. Within the questionnaire, follow-up questions regarding enrichment use revealed that some farms only provided enrichment in response to FD already observed in the flock. Therefore, the effect of enrichment for non-cage flocks should be interpreted with some caution.

It should be noted that this was an exploratory study, as it is the first of its kind in Canada, and thus the p-values exhibited should be considered exploratory [56]. Further investigation is needed regarding the impact of factors discussed here. Additionally, no age restrictions were imposed on flocks in lay in this study. It should therefore be recognized that the factors investigated may not have yet reflected their impact on feather cover when the feather assessment was performed for certain flocks newly brought into lay. It should also be acknowledged that data from all provinces were analyzed together; thus, any regional differences in farm practices, which were not distinguished by stratification, could have influence on the results found here. Furthermore, much of the literature comprises studies conducted in Europe where some flocks were not beak-trimmed, and where free-range and organic farming is more common practice than in Canada. Different methods of FD scoring regarding scales used and number of body regions scored also make comparison among study findings difficult.

Conclusion

Overall, a FD prevalence of approximately 26% was found in a survey of laying hen flocks across Canada, indicating that FP activity is a problem in non-cage systems within the country. Reduced feather cover has important implications for bird welfare (thermoregulation, housing navigation difficulties, and susceptibility to injury), as well as egg farmers (economic losses, low morale or motivation, reduced public support), and consumers (loss of trust in farming practices and animal caretaking). The investigation of housing, management, and genetic factors related to FD indicated that providing birds the opportunity to forage and dustbathe in litter areas in barns continues to be an important element in reducing FD in laying flocks. Cleanliness of the floor area, amount of manure in the barn, and air quality related to these factors should be considered in barns where manure is not removed until the end of lay; such farms could see FD improvement with more frequent manure removal and/or replacement of the litter. Finally, despite contrasting findings of the effect of enrichment on FD outcomes, diversity of the environment through pecking objects and toys is still encouraged for use in the laying barn while attention should be given to enrichment during rearing as well. The factors discussed here would benefit from a longitudinal follow-up study to further investigate the impact of management changes in FD prevention and to better inform the egg farming community on how to prevent FD as more flocks enter alternative housing systems.

Methods

Study objectives were achieved in three steps: 1) the design of a simplified and easy to use yet comprehensive FD scoring system that does not require handling to assess FD prevalence on-farm, 2) the design of a questionnaire about housing and management practices distributed to egg farmers currently using alternative systems across the country, and 3) linking farm characteristics and practices with the occurrence of FD through regression modelling.

Feather damage (FD) scoring system

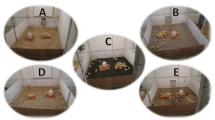

Farmers scored FD in their flock on a severity scale (Table 4) using a devised visual scoring system [24] adapted from previously validated scoring schemes [57,58,59,60]. Here, FD encompasses both the destruction of feathers and their loss, while the range of scores covered both good and poor feather condition along with an intermediate score for birds not severely affected by FD. The back/rump of the birds was inspected as this is a frequently targeted region of the body where damage typically reflects FP [28, 61]. The newly developed, simplified scoring system prioritized ease of use and time efficiency to encourage farmer participation.

For the recording of FD scores, farmers were instructed to score a sample of 50 birds selected proportionately from all sections of the barn, as described in previous studies [17, 59, 62]. Detailed and illustrated instructions were provided to assist farmers with selection of birds from different tiers/rows, slatted areas, and litter areas, depending on the housing system. Additionally, instructions included full-colour photographs of white- and brown-feathered birds representing the different scoring categories.

Questionnaire on housing and management practices

The questionnaire for laying hen farmers was based on a study by Lambton et al. [29], where associations between FP in laying hens and management and environmental factors in alternative systems was investigated. The current questionnaire was tailored using the research team’s expertise to be specific to current practices and standards in Canada [4]. Feedback was sought from federal and provincial egg boards, as well as commercial farmers, to receive input on how well questions reflected commercial settings, to determine if there were discrepancies in how questions would be interpreted, and to gauge overall comprehensiveness, i.e. whether the subject areas being asked about were sufficient, needed further inquiry, or could be pared down for better conciseness. The questionnaire covered the broad areas of flock and bird characteristics, housing features, litter management, flock health, staff duties, rearing history, diet, lighting, and air quality (Table 5). The questionnaire consisted of a mix of open-ended and closed questions with multiple answer options (see Additional file 1), and both English and French versions were made available.

Questionnaire distribution

Questionnaire distribution followed the procedures described by Decina et al. [25]. In brief, packages containing all documents (i.e., layer questionnaire, feather cover damage scoring guide, scoring sheets, cover letter, and return-addressed envelope) were posted to participating producers and also made available via Qualtrics® online survey software [63]. Both types of administration were used in order to accommodate groups that favour the ease and speed of an online survey format, as well as groups that may not have reliable access to the Internet or refrain from its use. Participants provided their consent through the return of the questionnaire in agreement with the Tri-Council Policy Statement: Ethical Conduct for Research Involving Humans – TCPS 2 (2018). This study was approved by the University of Guelph Research Ethics Board (REB17–06-010).

Distribution was facilitated through the provincial egg boards to target egg producers that housed flocks in non-cage housing systems and to ensure participant privacy while achieving geographic proportionality. Each package was assigned a 3-digit numeric code in order to ensure all package documents from a participant would remain together throughout the analysis. The data collection period ran from October to December 2017 with reminders sent out by the egg boards 2–4 weeks after initial distribution and two weeks before the end of data collection.

Statistical methods

Statistical analysis was conducted similarly as for the furnished cage flocks as described by Decina et al. [25], but with a focus on the non-cage flocks. In brief, the percentage of birds with a FD score greater than zero was calculated to estimate the FD prevalence within a flock. Associations between FD prevalence and the different factors investigated through the questionnaire were analyzed using R version 3.4.3 “Kite-Eating Tree” [64] in combination with RStudio [65].

Model building

Double manual entry of questionnaire responses was used to limit errors. Variables were screened for excessive missing values (> 50% of responses missing) or insufficient variation (e.g. a proportion of responses within one category of approximately > 0.85), and those were subsequently excluded from further investigation. Several variables were retrospectively collapsed to avoid rare or unobserved categories. For example, due to only a small proportion of farmers indicating different, specific breeds, this variable could not be included, and instead, feather colour was used as the closest proxy. Following this, a total of 61 variables were included in univariable analyses. Variables were examined for collinearity, and associations between each variable were assessed using Spearman rank-correlations (continuous variables) and Pearson’s χ2-tests (categorical variables). Twenty-four of the 61 variables reached the criterion of P ≤ 0.25, or were considered biologically relevant, and were used as predictor variables for FD prevalence in multivariable analysis using a mixed linear regression model with a forward variable selection approach. The final model included variables that were significant (P ≤ 0.05) and/or contributed to a high adjusted R2. Relevant interactions between predictor variables were assessed, but none were found to significantly influence the final model. Centering of flock age at 40 weeks was done to allow for a more intuitive interpretation of FD prevalence.

Diagnostic procedures

Normality of residuals and homogeneity of variance were graphically inspected using QQ-plots and scatterplots of standardized residuals against fitted values [66]. The Variance Inflation Factor (VIF) was used to assess collinearity, while a boxplot of model residuals was used to check for outliers, and Cook’s distance was used to check for influential data points.

Availability of data and materials

The dataset used and analyzed during the current study is available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- FD:

-

Feather Damage

- FP:

-

Feather Pecking

References

EFC. Annual Report 2017. Ottawa, Canada: Egg Farmers of Canada; 2018.

Bejaei M, Wiseman K, Cheng KM. Influences of demographic characteristics, attitudes, and preferences of consumers on table egg consumption in British Columbia. Canada Poult Sci. 2011;90(5):1088–95.

Noakes S. Cage-free eggs only a goal for major Canadian grocers by 2025 | CBC news. CBC News 2016.

National Farm Animal Care Council (NFACC). Code of practice for the care and handling of pullets and laying hens. Ottawa, Canada; 2017.

Savory CJ. Feather pecking and cannibalism. Worlds Poult Sci J. 1995;51(2):215–9.

McAdie TM, Keeling LJ. Effect of manipulating feathers of laying hens on the incidence of feather pecking and cannibalism. Appl Anim Behav Sci. 2000;68(3):215–29.

Glatz PC. Effect of poor feather cover on feed intake and production of aged laying hens. Asian-Australas J Anim Sci. 2001;14(4):553–8.

Scanes CG, editor. Sturkie’s avian physiology. 6th ed. London: Academic Press; 2015.

LeBlanc S, Tobalske B, Quinton M, Springthorpe D, Szkotnicki B, Wuerbel H, et al. Physical health problems and environmental challenges influence balancing behaviour in laying hens. PLoS One. 2016;11(4):1–16.

LeBlanc C, Tobalske B, Bowley S, Harlander-Matauschek A. Development of locomotion over inclined surfaces in laying hens. Animal. 2018;12(3):585–96.

van Zeeland YRA, Schoemaker NJ. Plumage disorders in psittacine birds - part 1: feather abnormalities. Eur J Companion Anim Pract. 2014;24(1):34–47.

Rubinstein J, Lightfoot T. Feather loss and feather destructive behavior in 728 pet birds. Vet Clin North Am - Exot Anim Pract. 2014;17(1):77–101

Lindström Å, Visser GH, Daan S. The energetic cost of feather synthesis is proportional to basal metabolic rate. Physiol Zool. 1993;66(4):490–510.

Hartcher KM, Wilkinson SJ, Hemsworth PH, Cronin GM. Severe feather-pecking in non-cage laying hens and some associated and predisposing factors: a review. Worlds Poult Sci J. 2016;72(1):103–14.

Lambton SL, Knowles TG, Yorke C, Nicol CJ. The risk factors affecting the development of gentle and severe feather pecking in loose housed laying hens. Appl Anim Behav Sci. 2010;123(1–2):32–42.

Gilani A-M, Knowles TG, Nicol CJ. The effect of rearing environment on feather pecking in young and adult laying hens. Appl Anim Behav Sci. 2013;148:54–63.

de Haas EN, Bolhuis JE, de Jong IC, Kemp B, Janczak AM, Rodenburg TB. Predicting feather damage in laying hens during the laying period. Is it the past or is it the present? Appl Anim Behav Sci. 2014;160(1):75–85.

Blokhuis HJJ. Feather-pecking in poultry: its relation with ground-pecking. Appl Anim Behav Sci. 1986;16(1):63–7.

Rodenburg T, Van Krimpen M, DE Jong I, DE Haas E, Kops M, Riedstra B, et al. The prevention and control of feather pecking in laying hens: identifying the underlying principles. Worlds Poult Sci J. 2013;69(2):361–73.

Brunberg EI, Rodenburg TB, Rydhmer L, Kjaer JB, Jensen P, Keeling LJ. Omnivores going astray: a review and new synthesis of abnormal behavior in pigs and laying hens. Front Vet Sci. 2016;3:57.

Bennett RM, Jones PJ, Nicol CJ, Tranter RB, Weeks CA. Consumer attitudes to injurious pecking in free-range egg production. Anim Welf. 2016;25(1):91–100.

The Canadian Centre for Food Integrity. Public Trust Research. 2017:2017.

Palczynski L, Buller H, Lambton S, Weeks C. Farmer attitudes to injurious pecking in laying hens and to potential control strategies. Anim Welf. 2016;25(1):29–38.

Decina C, Berke O, van Staaveren N, Baes CF, Harlander-Matauscheck A. Development of a scoring system to assess feather damage in Canadian laying hen flocks. Animals. 2019;9(7):436.

Decina C, Berke O, van Staaveren N, Baes CF, Widowski TM, Harlander-Matauschek A. An investigation of associations between management and feather damage in Canadian laying hens housed in furnished cages. Animals. 2019;9(4):135.

van Staaveren N, Decina C, Baes CF, Widowski TM, Berke O, Harlander-Matauschek A. A description of laying hen husbandry and management practices in Canada. Animals. 2018;8(7):114.

Huber-Eicher B, Sebö F. The prevalence of feather pecking and development in commercial flocks of laying hens. Appl Anim Behav Sci. 2001;74(3):223–31.

Bilcik B, Keeling LJ. Changes in feather condition in relation to feather pecking and aggressive behaviour in laying hens. Br Poult Sci. 1999;40(4):444–51.

Lambton SL, Nicol CJ, Friel M, Main DCJ, McKinstry JL, Sherwin CM, et al. A bespoke management package can reduce levels of injurious pecking in loose-housed laying hen flocks. Vet Rec. 2013;172(16):423.

Gunnarsson S, Keeling LJ, Svedberg J. Effect of rearing factors on the prevalence of floor eggs, cloacal cannibalism and feather pecking in commercial flocks of loose housed laying hens. Br Poult Sci. 1999;40(1):12–8.

Bestman MWP, Wagenaar JP. Farm level factors associated with feather pecking in organic laying hens. Livest Prod Sci. 2003;80(1):133–40.

Sherwin CM, Richards GJ, Nicol CJ. Comparison of the welfare of layer hens in 4 housing systems in the UK. Br Poult Sci. 2010;51(4):488–99.

Lay DC Jr, Fulton RM, Hester PY, Karcher DM, Kjaer JB, Mench JA, et al. Hen welfare in different housing systems. Poult Sci. 2011;90(1):278–94.

Zeltner E, Klein T, Huber-Eicher B. Is there social transmission of feather pecking in groups of laying hen chicks? Anim Behav. 2000;60(2):211–6.

Appleby MC, Hughes BO, Elson HA. Poultry production systems: behaviour, management and welfare. Wallingford: CAB International; 1992.

Tauson R. Management and housing systems for layers – effects on welfare and production. Worlds Poult Sci J. 2005;61(3):477–90.

European Food Safety Authority. The welfare aspects of various systems of keeping laying hens. EFSA J. 2005;197:1–23.

Green LE, Lewis K, Kimpton A, Nicol CJ. Cross-sectional study of the prevalence of feather pecking in laying hens in alternative systems and its associations with management and disease. Vet Rec. 2000;147:233–8.

Huber-Eicher B, Wechsler B. The effect of quality and availability of foraging materials on feather pecking in laying hen chicks. Anim Behav. 1998;55(4):861–73.

Dixon LMM, Duncan IJHJH, Mason G. What’s in a peck? Using fixed action pattern morphology to identify the motivational basis of abnormal feather-pecking behaviour. Anim Behav. 2008;76(3):1035–42.

Johnsen PF, Vestergaard KS, Nørgaard-Nielsen G. Influence of early rearing conditions on the development of feather pecking and cannibalism in domestic fowl. Appl Anim Behav Sci. 1998;60(1):25–41.

Nicol CJ, Lindberg AC, Phillips AJ, Pope SJ, Wilkins LJ, Green LE. Influence of prior exposure to wood shavings on feather pecking, dustbathing and foraging in adult laying hens. Appl Anim Behav Sci. 2001;73(2):141–55.

de Haas EN, Bolhuis JE, Kemp B, Groothuis TGG, Rodenburg TB. Parents and early life environment affect behavioral development of laying hen chickens. PLoS One. 2014;9(3):e90577.

David B, Mejdell C, Michel V, Lund V, Moe RO. Air quality in alternative housing systems may have an impact on laying hen welfare. Part II -ammonia Animals. 2015;5(3):886–96.

Donham KJ, Cumro D, Reynolds SJ, Merchant JA. Dose-response relationships between occupational aerosol exposures and cross-shift declines of lung function in poultry workers: recommendations for exposure limits. J Occup Environ Med. 2000;42(3):260–9.

Drake KA, Donnelly CA, Dawkins MS. Influence of rearing and lay risk factors on propensity for feather damage in laying hens. Br Poult Sci. 2010;51(6):725–33.

Zhao Y, Shepherd TA, Li H, Xin H. Environmental assessment of three egg production systems -part I: monitoring system and indoor air quality. Poult Sci. 2015;94(3):518–33.

Widowski TM, Classen H, Newberry RC, Petrik M, Schwean-Lardner K, Cottee SY, et al. Code of practice for the care and handling of pullets, layers, and spent fowl: poultry (layers): review of scientific research on priority issues. Canada: Lacombe, AB; 2013.

Anderson DP, Beard CW, Hanson RP. Influence of poultry house dust, ammonia, and carbon dioxide on the resistance of chickens to Newcastle disease virus. Avian Dis. 1966;10(2):177–88.

Oyetunde OO, Thomson RG, Carlson HC. Aerosol exposure of ammonia, dust and Escherichia coli in broiler chickens. Can Vet J. 1978;19:187–93.

Anderson DP, Beard CW, Hanson RP. The adverse effects of ammonia on chickens including resistance to infection with Newcastle disease virus. Avian Dis. 1964;8(3):369–79.

McAdie TM, Keeling LJ, Blokhuis HJ, Jones RB. Reduction in feather pecking and improvement of feather condition with the presentation of a string device to chickens. Appl Anim Behav Sci. 2005;93:67–80.

University of Bristol. FeatherWel: Improving Feather Cover. 2013.

Jones RB, McAdie TM, McCorquodale C, Keeling LJ. Pecking at other birds and at string enrichment devices by adult laying hens. Br Poult Sci. 2002;43(3):337–43.

Glatz PC. Beak trimming method: A review. Asian Austral J anim Sci. 2000:1619–37.

Matthews R, Wasserstein R, Spiegelhalter D. The ASA’s p-value statement, one year on. Significance. 2017;14:38–41.

Bright A, Jones TA, Dawkins MS. A non-intrusive method of assessing plumage condition in commercial flocks of laying hens. Anim Welf. 2006;15:113–8.

Tauson R, Kjaer J, Maria GA, Cepero R, Holm K-E. Applied scoring of integument and health in laying hens. Anim Sci Pap Reports. 2005;23(Supplement 1):153–9.

University of Bristol. AssureWel Laying Hens Assessment protocol. 2013.

Giersberg MF, Spindler B, Kemper N. Assessment of plumage and integument condition in dual-purpose breeds and conventional layers. Animals. 2017;7(12).

Nicol CJ, Bestman M, Gilani A-M, De Haas EN, De Jong IC, Lambton S, et al. The prevention and control of feather pecking: application to commercial systems. Worlds Poult Sci J. 2013;69(4):775–88.

Heerkens JLT, Delezie E, Kempen I, Zoons J, Ampe B, Rodenburg TB, et al. Specific characteristics of the aviary housing system affect plumage condition, mortality and production in laying hens. Poult Sci. 2015;94(9):2008–17.

Qualtrics. Qualtrics. Provo, Utah, USA; 2017.

R Core Team. R: a language and environment for statistical computing. Vienna: R Foundation for statistical Computing; 2017.

RStudio Team. RStudio: integrated development environment for R. Boston: RStudio, Inc.; 2016.

Dohoo I, Martin W, Stryhn H. Veterinary epidemiologic research. 2nd ed. Charlottetown, Prince Edward Island: VER Inc.; 2009. p. 339–58.

Acknowledgements

This research was done in partial fulfilment of the requirements for completion of a Master of Science degree by Caitlin Decina. Preliminary results were presented at the Poultry Science Association (PSA) 107th Annual Meeting, San Antonio, Texas, US, 23 – 26 July 2018 [Poultry Science 97 (E-Supplement 1), p. 73]. A special thanks to Prof. Christine Nicol from the Royal Veterinary College, University of London, for providing the research team with the questionnaire as used in Lambton et al., 2013 (Vet Record), which formed the basis of this study. The authors also thank all the laying hen farmers across Canada who generously offered their time and input by participating in this study.

Funding

The authors acknowledge the Egg Farmers of Canada (recipient: Dr. Harlander-Matauschek) for funding this research as part of the ‘Towards an Understanding of Beautiful Feather Cover in Laying Hens’ project. We also acknowledge the Mitacs Elevate Fellowship for providing additional funding for Dr. van Staaveren. The Egg Farmers of Canada played no role in the design of the study, analysis, interpretation of data, or in writing of the manuscript, however, the organization did play a role in collection of the data by assisting with the distribution of the questionnaires to participating farmers.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors (CD, OB, NvS, CB, TW, and AH) made substantial intellectual contributions to the conception of the study, study design and methodology, and interpretation of the data. CD and NvS carried out data collection and conducted statistical analysis, with assistance from OB. CD drafted the first version of the manuscript. CD, OB, NvS, CB, TW, and AH provided substantive input and contributions to manuscript revision. All authors (CD, OB, NvS, CB, TW, and AH) read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study was approved by the University of Guelph Research Ethics Board (REB17–06-010). Informed consent was obtained from all participants, as indicated by the return of the questionnaire by the participant in agreement with the Tri-Council Policy Statement: Ethical Conduct for Research Involving Humans – TCPS 2 (2018). All human participants consented to the use of their data in the generation of findings in this project. No personal or identifying information was shared in the communication of results.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Additional file 1.

Laying farms questionnaire (English versions). Complete questionnaire on housing and management practices distributed to egg farmers with alternative housing systems (English version).

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Decina, C., Berke, O., van Staaveren, N. et al. A cross-sectional study on feather cover damage in Canadian laying hens in non-cage housing systems. BMC Vet Res 15, 435 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12917-019-2168-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12917-019-2168-2