Abstract

Smaller groups of victims of violence, abuse, neglect or exploitation – such as male victims of intimate partner violence (IPV), victims of elder abuse, victims of abuse by carers, victims of parent abuse, victims of human trafficking, girls and boys below 18 years engaging in sex work, victims of sexual exploitation by gangs or groups and victims of honour based violence (such as forced marriages and female genital mutilation) – are often in contact with the health care system without being identified as such and frequently do not receive appropriate treatment. To address this problem, two things need to happen: 1) that ALL groups of victims of violence, abuse, neglect or exploitation are explicitly listed in policies and protocols, and 2) that both the similarities as well as the differences between the groups with regard to identification, support and referral – described in this article – are explained, so that health providers are appropriately supported in this important function.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background: Lesser-known victims of violence, abuse, neglect or exploitation

A positive development in global public health and social policy in the past few decades has been the recognition of the importance of adequate responses to victims of violence, abuse, neglect or exploitation (‘VANE’, from hereon). This has led to much improved policies and practices supporting female victims of intimate partner violence (IPV) and victims of child abuse. However, other specific groups of victims of VANE are often neglected in current policies and service delivery. As a result, health providers lack knowledge of these lesser-known groups, often meaning victims are in contact with the health system without being identified as such [1, 2] and frequently do not receive appropriate treatment [1,2,3]. E.g., while up to 88% of victims of human trafficking encounter a health provider while being trafficked, less than 20% of providers knows enough to identify or appropriately support them [4, 5]. Further examples of these often-neglected groups are provided in Table 1, in addition to IPV against women and child abuse. The table also lists their global and UK one-year prevalence.

Main text: Similarities and differences between various groups of victims of VANE

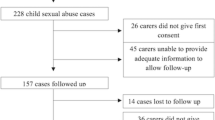

It is key that health providers recognize both the similarities and differences between these groups. Similar steps may be taken to a) identify, b) support and c) refer victims (if needed) (Fig. 1):

-

1.

researching and documenting signs of VANE (including asking about VANE in the first place – that’s ‘step 0’ in this model);

-

2.

consulting peers and experts;

-

3.

deciding if it is appropriate to interview the patient (and/or others involved) and if yes, doing so;

-

4.

conferring with other professionals who know the patient (e.g., teachers); and

-

5.

reaching decisions about whether:

-

A)

the situation needs to be ‘reported’, meaning that the health provider chooses to discuss the situation with an organization with a legal mandate to 1) provide advice on domestic violence or child abuse and 2) arrange referral when needed (‘reporting’ is mandatory in some countries for certain types of cases of VANE. E.g., in the Netherlands, this is mandatory when i) there is (risk of) acute or structural unsafety, or ii) when the health provider is not able to provide or organise help/care him−/herself. This ensures that VANE professionals are involved in decision-making processes when needed);

-

B)

care/help can be provided by the health provider him−/herself or whether the patient needs to be referred.

To be able to make these two decisions, two questions need to be answered about the situation: 1) Is there a suspicion of VANE? and 2) is there acute or structural unsafety? [6,7,8].

-

A)

Five steps for deciding how to respond as a health provider when you suspect someone is a victim of violence, abuse, neglect or exploitation (VANE). This figure is based on the identification, support and referral protocol in the Netherlands; [6,7,8] other countries may have their own protocols that may differ from the one described here. In the Netherlands, the organization with a legal mandate to 1) provide advice on domestic violence or child abuse and 2) arrange referral when needed, is “Veilig Thuis”, meaning “Safe at Home”. Whenever possible, ‘reporting’ should be done with the consent of the patient, but when the health provider is of the opinion there is acute and/or structural unsafety, he/she may be justified or even obligated to break confidentiality and report the situation to this organization against the wishes of the patient

Recognizing that these general steps are the same for all types of VANE makes it easier for providers to respond appropriately to lesser-known types, as they can follow the same protocol.

At the same time, there are differences between the various groups of victims that providers need to take note of (Additional file 1). In terms of identification, the signs of VANE that could lead to identification differ by group, e.g., the signs of honour-based violence are quite different to those for IPV. Similarly, the risk factors that make someone more likely to be a victim differ by group, e.g., specific risk groups are known for female genital mutilation and parent abuse. Besides this, there are specific identification, support and referral considerations for most groups, around, for example:

-

assessing safety, e.g., with human trafficking criminal networks may be involved leading to different safety assessments;

-

breaking confidentiality, e.g., considerations around breaking confidentiality to ‘report’ VANE are different for VANE against adults than for child abuse [7];

-

urgency, e.g., victims of some types of VANE, such as parent abuse and honour-based violence, typically present very late, necessitating swift action;

-

communication, e.g., with some types of VANE, such as honour-based violence or cross-border human trafficking, if patients do not speak your language, it is important to speak to them via an independent translator when they are accompanied by someone (it should be the policy to speak to a potential victim alone for all types of VANE).

In many countries, protocols are available, either at national or local level, to guide health providers and social workers in a) identifying, b) supporting and c) referring victims (if needed). Unfortunately, these protocols are often limited in the types of VANE that they cover [7]. Explicitly including ALL types of VANE in such protocols increases the awareness of lesser-known groups, makes it easier for providers to respond appropriately to all types of victims using one protocol (Fig. 1) and makes providers take note of the differences between the groups of victims (Additional File 1). Therefore, at a policy level, explicitly including all groups of victims of VANE in relevant policies and protocols is key in improving standards of care for ALL the groups in Table 1.

This may be aided by using a more inclusive umbrella term to describe these groups. Currently, umbrella terms that are used frequently are ‘domestic violence’ (this is limited to violence by family members or other persons in a domestic setting) and ‘IPV’ (this is limited to violence between partners), excluding victims of violence by people outside the home (e.g., abuse by gangs or VANE by someone in the workplace) or by non-partners respectively. Also, the term ‘violence’ is often interpreted quite narrowly, e.g., as meaning only physical violence (although arguably a more broad interpretation is possible); therefore, it is better to speak about ‘violence, abuse, neglect or exploitation’. These exclusions are missed opportunities, because clearly it is beneficial for victims of any type of VANE if health providers (or other professionals) are able to a) identify, b) support and, if needed, c) refer them appropriately. To address some of these problems, the Netherlands have opted to use the term ‘Violence in power-imbalanced relationships’, [9] which includes all types of VANE in any relationship (parents, partners, teachers, health providers, work colleagues, etcetera), regardless of setting – that is, all groups in Table 1. By using the word ‘power-imbalanced’ this term stresses that victims of VANE often have an unequal power relationship with the perpetrator. Although the word ‘violence’ in this term is mostly broadly interpreted in the Netherlands as meaning VANE, a further improvement may be to speak of ‘Violence, abuse, neglect or exploitation in power-imbalanced relationships’.

Conclusion

Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) 5 and 16 ask that we aim to end ALL forms of violence, neglect, abuse and exploitation. To this end, we recommend health ministries and professional health provider organizations ensure two things happen: 1) that all groups of victims of VANE are explicitly listed in policies and protocols, and 2) that both the similarities (e.g., Fig. 1) as well as the differences (e.g., Additional file 1) between the groups with regard to identification, support and referral are explained, so that health providers are appropriately supported in this important function. It may also be beneficial to adopt a more inclusive umbrella term to describe all types of VANE together.

Notes

We would like to note that in speaking about ‘health providers’ in this article we mean the broadest possible range of health and social care workers, including, for example, all medical and nursing professions, physiotherapists, dentists, midwives and social workers.

Abbreviations

- IPV:

-

Intimate partner violence

- SDGs:

-

Sustainable Development Goals

References

Ahn R, Alpert EJ, Purcell G, Konstantopoulos WM, McGahan A, Cafferty E, et al. Human trafficking: review of educational resources for health professionals. Am J Prev Med. 2013;44:283–9 Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/23415126. [cited 2013 Mar 27].

Alt KL, Nguyen AL, Meurer LN. The Effectiveness of Educational Programs to Improve Recognition and Reporting of Elder Abuse and Neglect: A Systematic Review of the Literature. J Elder Abuse Negl. 2011;23:213–33 Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/27119527. [cited 2017 Sep 13].

Balfour J, Abdulcadir J, Say L, Hindin MJ. Interventions for healthcare providers to improve treatment and prevention of female genital mutilation: a systematic review. BMC Health Serv Res. 2016;16:409 Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/27542732. [cited 2017 Sep 13].

Ross C, Dimitrova S, Howard LM, Dewey M, Zimmerman C, Oram S. Human trafficking and health: a cross-sectional survey of NHS professionals’ contact with victims of human trafficking. BMJ Open. 2015;5:e008682 Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/26293659. [cited 2017 Aug 2].

Hoofdstuk 4: Zicht op mensenhandel in de medische sector. Mensenhandel Tiende Rapp van Natl Rapp. Den Haag: Nationaal Rapporteur Mensenhandel en Seksueel Geweld tegen Kinderen; 2017.

KNMG-meldcode Kindermishandeling en huiselijk geweld. Utrecht: KNMG; 2014.

Model Reporting Code Domestic Violence and Child Abuse. Action plan for responding to signs of domestic violence and child abuse. Den Haag: Dutch Ministry of Health Welfare and Sport; 2013. Available from: http://www.government.nl/government/documents-and-publications/reports/2013/03/14/model-reporting-code-domestic-violence-and-child-abuse.html

Government of the Netherlands. Domestic violence and child abuse protocol [of the Netherlands] . Available from: https://www.government.nl/topics/domestic-violence/domestic-violence-and-child-abuse-protocol, [cited 2018 Sep 20]

Handelingsprotocol.nl, Vormen van Huiselijk Geweld. Samen Veilig Midden-Nederland / Veilig Thuis. https://www.handelingsprotocol.nl/utrecht-ko-stap-1-signaleren-3/utrecht-vormen-huiselijk-geweld. Accessed 8 Oct 2018.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the UK National Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Children for their help in finding statistics on child maltreatment.

Funding

The writing of this article was made possible by funding from: VSBfonds, Prins Bernhard Cultuurfonds, Stichting dr. Hendrik Muller’s Vaderlandsch Fonds, Stichting Studiefonds KETEL 1, Buwalda Stichting. The funding organizations had no input in any stage of the research, analysis or writing. The writers are independent from the funders.

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable; not a research study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

RV is the main author of the article and conceived the idea for the article; all other authors contributed equally to conception, development and writing of the article. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interest

The author(s) declare(s) that they have no competing interests.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable; not a research study.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Additional files

Additional file 1:

Examples of differences between smaller groups of victims of violence, abuse, neglect or exploitation (VANE) in terms of identification, support and referral: an overview for health providers and social workers. (DOCX 36 kb)

Additional file 2:

Sources used in the development of Table 1. (DOCX 47 kb)

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Viergever, R.F., Thorogood, N., Wolf, J.R. et al. Supporting ALL victims of violence, abuse, neglect or exploitation: guidance for health providers. BMC Int Health Hum Rights 18, 39 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12914-018-0178-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12914-018-0178-y