Abstract

Background

Home-based care is used in many countries to increase quality of life and limit hospital stay, particularly where public health services are overburdened. Home-based care objectives for HIV/AIDS can include medical care, delivery of antiretroviral treatment and psychosocial support. This review assesses the effects of home-based nursing on morbidity in people infected with HIV/AIDS.

Methods

The trials studied are in HIV positive adults and children, regardless of sex or setting and all randomised controlled. Home-based care provided by qualified nurses was compared with hospital or health-facility based treatment. The following electronic databases were searched from January 1980 to March 2015: AIDSearch, CINAHL, Cochrane Register of Controlled Trials, EMBASE, MEDLINE and PsycINFO/LIT, with an updated search in November 2016. Two authors independently screened titles and abstracts from the electronic search based on the study design, interventions and types of participant. For all selected abstracts, full text articles were obtained. The final study selection was determined with use of an eligibility form. Data extraction was performed independently from assessment of risk of bias. The results were analysed by narrative synthesis, in order to be able to obtain relevant effect measures plus 95% confidence intervals.

Results

Seven studies met the inclusion criteria. The trial size varied from 37 to 238 participants. Only one trial was conducted in children. Five studies were conducted in the USA and two in China. Four studies looked at home-based adherence support and the rest at providing home-based psychosocial support. Reported adherence to antiretroviral drugs improved with nurse-led home-based care but did not affect viral load. Psychiatric nurse support in those with existing mental health conditions improved mental health and depressive symptoms. Home-based psychological support impacted on HIV stigma, worry and physical functioning and in certain cases depressive symptoms.

Conclusions

Nurse-led home-based interventions could help adherence to antiretroviral therapy and improve mental health. Further larger scale studies are needed, looking in more detail at improving medical care for HIV, especially related to screening and management of opportunistic infections and co-morbidities.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

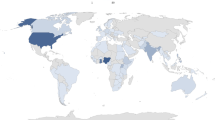

HIV/AIDS is a significant cause of morbidity and mortality in low and middle-income countries (LMICs), where health services already contend with poor infrastructure and limited resources including staff, drugs and equipment. Approximately 36.7 million people are living with HIV and around 52% of these are in Sub-Saharan Africa [1]. In 2015, an estimated 2.1 million people became newly infected with HIV/AIDS while 1.1 million of those with HIV/AIDS died [1].

The 2016 World Health Organisation (WHO) guidelines broaden the number of people eligible to start life-saving antiretroviral therapy (ART) [2]. Although these changes can improve clinical outcomes and reduce the incidence of HIV, they pose a challenge for public health services already overburdened with limited human and financial resources. Global coverage of antiretroviral therapy increased to 46% at the end of 2015 but disparities remain between high and low income countries [1].

Barriers to accessing and retaining care include amongst others transport costs, long waiting times and a shortage of healthcare staff [3]. Decentralising HIV treatment to community or home based settings and task-shifting using non-physician health workers for the initiation and maintenance of ART may help to overcome some of these problems, and these measures are being adopted as key management strategies [4,5,6].

Home-based care

The WHO defines home-based care (HBC) as any form of care given to ill people in their homes, including physical, psychosocial, palliative and spiritual activities [7]. There are various types of HBC including integrated HBC where all service providers are involved, single service HBC involving one organisation, and informal HBC with no formal support structure [8]. HBC can be carried out by a variety of people including qualified healthcare practitioners, nurses, trained lay community health workers, peer health workers and HBC volunteers [9].

Providing care in the home can overcome some of the barriers to care, such as transport costs and waiting times, and help to reduce the burden on health facilities [10]. Other benefits of HBC include lower costs at both individual and country level, personalised care and being in familiar surroundings. It can also reduce demand on hospital beds and increase effective time use in hospitals [10].

Home-based care for HIV

HBC has been defined by the Committee on a National Strategy for AIDS (CNSA) for the USA as care at the patient’s residence to supplement or replace hospital care including medical management, palliative care and social support [8]. HBC objectives for HIV/AIDS can include improved medical care, delivery of ART and improved psychosocial well-being (Fig. 1 Home-based care as a management strategy for people with HIV). It could have positive social outcomes by helping to reduce the stigma surrounding HIV, thereby improving support, access and adherence to ART and uptake of testing [10, 11]. An integrated approach using HBC to provide co-ordinated care for a number of conditions has been suggested, for instance combining HIV and tuberculosis management [12, 13].

Recent expansion of ART programmes has led to a growing emphasis on the decentralisation of HIV treatment in LMICs. Kredo assessed the effects of decentralised HIV care in relation to both initiation and maintenance of ART [5]. Wringe reviewed whether the conditions are in place to effectively scale up HBC programmes for increased ART, in terms of available human resources, health systems and funding mechanisms. They concluded that sustainable funding needs to be ensured, and policies to encourage staff retention and service integration are needed [10].

Home-based care for other conditions

A number of reviews have examined the effects of home care for a variety of conditions. Okwundu found that home or community-based programmes for treating malaria could increase the number of people who receive appropriate anti-malarial treatment and may reduce all-cause mortality [14]. For cardiovascular disease, Clark found that home-based secondary prevention programmes conducted by health professionals are as effective as hospital based cardiac rehabilitation, and considerably lower in cost [15]. A study looking at end of life care at home for terminal patients supported the use of home care programmes for increasing the numbers of patients who will die at home [16]. In contrast, Smeenk concluded that the effectiveness of home care programmes for patients with terminal cancer remains unclear [17].

Task-shifting

Task shifting from medical doctors to nurses is a potentially effective strategy to overcome the medical workforce shortage and to address the needs associated with chronic HIV/AIDS [13]. The increasing use of lay health workers to fill gaps in the work force raises the issues of training required and the quality of care provided. A review examining the use of lay health workers in the management of infectious diseases found them to be effective for improving tuberculosis outcomes but there was insufficient evidence to make a conclusion regarding adherence support in HIV/AIDS [18].

Kredo found that there is probably no reduction in the quality of care when trained nurses or community health workers initiate and maintain ART. When nurses initiate and maintain ART, there may also be lower loss to follow-up compared with doctors [6]. More research is needed into the level of training required and the ability of these workers to perform effectively whilst taking on multiple roles [9, 19].

Why is it important to do this review?

In addition to the delivery of ART, other current key issues in the multidimensional care of HIV/AIDS include counselling and home-based testing, pre-ART care (such as repeating eligibility assessment), delivery of preventative interventions, distribution of prophylaxis, treatment of opportunistic infections and supportive psychosocial activities.

Young found a range of HBC models and interventions for HIV but these were generally from small studies and the majority were based in developed countries [20]. Since this review was published, there has been a change in the evidence with more focus on HBC in LMICs. Home-based HIV voluntary counselling and testing has been found to have the potential to increase uptake in developing countries [21]. Nurses are an important element of HBC for HIV but have not been covered in depth in Young or any other recent review. This review assesses the effects of home-based nursing to reduce morbidity in people infected with HIV/AIDS.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

We included all randomised controlled trials (RCTs) conducted amongst HIV/AIDS positive individuals, adults and children, comparing home-based care, including all forms of treatment, care and support offered in the HIV/AIDS positive person’s home by qualified nurses who have received a formal professional certificate or tertiary education degree, compared to hospital or health-facility based treatment. Home-based HIV voluntary counselling and testing was excluded as it is covered in Bateganya [21]. Initiation and delivery of ART was excluded as it is covered in Kredo [5]. We considered various outcomes including progression to AIDS, death, psychosocial outcomes (mood scores, stigma, patient and carer preferences), quality of care, quality of life, inpatient days, and number and type of opportunistic infections.

Search methods for identification of studies

The following electronic databases were searched from 1980 to March 2015: Cochrane Register of Controlled Trials, MEDLINE, EMBASE, AIDSearch, CINAHL, PsycINFO/LIT, with an updated search in MEDLINE in November 2016. Detailed search strategies were compiled for each database searched (Table 1 details the MEDLINE search strategy). Clinicaltrials.gov and the WHO International Clinical Trials Registry Platform were searched in March 2015 to identify on-going trials. The strategy was iterative, in that references of included studies were searched for additional references. All languages were included.

Selection of studies, data collection and analysis

Titles, abstracts and descriptor terms of the electronic search results were screened independently by two authors for relevance based on predefined eligibility criteria. Full text articles were obtained of all selected abstracts and final eligibility assessed. Data including administrative details, study design, details of the intervention and control, and outcomes were extracted independently by two authors using a standardised data extraction form.

The risk of bias of included studies was also evaluated independently by two authors using the Cochrane risk of bias tool. We assessed and summarised the following main items in the ‘Risk of Bias’ table: sequence generation, allocation concealment, blinding of participant and personnel, blinding of outcome assessment, whether incomplete outcome data were adequately addressed, selective reporting and any other bias.

Missing or inadequate data were addressed by contacting authors. We resolved disagreements by discussion.

Relevant effect measures and the 95% confidence intervals (CI) were reported. We planned to assess sources of clinical and methodological heterogeneity by looking at characteristics of studies, evaluating similarity between type of participants, intervention used and outcomes. However, due to the varied outcomes used in the included studies no meta-analysis could be conducted.

Results

Description of studies

Seven studies met the inclusion criteria (Fig. 2 Flow diagram of study selection). In addition, we identified one on-going trial currently being conducted in Kenya investigating home-based directly observed ART [22]. Fifty studies were excluded. Reasons for exclusion are detailed in Table 2.

Individuals were randomised in each of these seven studies. Trial sizes varied from n = 37 to n = 238. Only one trial was conducted in children [23] whilst the rest were conducted in adults (≥18 years). One trial focused on female adults [24] and the others included males and females. Five studies were conducted in the USA [23,24,25,26,27] and two in China [28, 29].

The interventions studied and outcomes measured varied between studies (Table 3). Four studies could be classified under home-based adherence support [23, 27,28,29]. Five studies investigated providing home-based psychosocial support [24,25,26, 28, 29].

Detailed information on the participants, interventions, controls and outcomes can be found in Table 3.

Risk of bias in included studies

The risk of bias assessment is summarised in Table 4.

Allocation (selection bias)

All trials stated that participants were randomised. Five trials used adequate methods for generating the allocation sequence. Of these five trials, two used random number tables [23, 24], one used a computer generated algorithm [26] and two used a stratified randomisation procedure [27, 29]. Allocation concealment was adequate in two trials [23, 26] and not reported in the remaining trials.

Blinding (performance bias and detection bias)

In Williams 2006 all personnel (except the home intervention team) and the interviewers were blind throughout the course of the study whereas in Hanrahan and Miles, only the data collectors were blinded [24, 26, 27]. Blank was designed to be single blind for the research staff but participants sometimes disclosed information, which made it possible to identify their experimental status [25].

In Williams 2014 there was no blinding of the participants but it was unclear whether the outcome assessors were blinded [29]. Berrien used no blinding and Wang did not report blinding [23, 28].

Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias)

Three trials reported a loss to follow up of less than 20% and two reported a loss to follow up of less than 30% [23, 26, 28]. Miles had a high loss to follow up of 51% in the intervention group and 58% in the control group [24]. One study did not report loss to follow up [25].

Selective reporting (reporting bias)

All outcomes stated were reported.

Effects of interventions

The effects of the various interventions are summarised in Table 5.

Adherence support

Four studies, one in children [23] and three in adults [27,28,29] examined the effects of an intensive home based nursing programme compared to standard care on adherence to ART. Berrien, Williams 2006 and Williams 2014 also reported viral load and CD4 counts [23, 27, 29]. However, due to differences in the way these three outcomes were measured and reported we could not do a meta-analysis.

In Berrien’s study (n = 37) a home care registered nurse made eight pre-planned home visits over three months, aiming to increase patient understanding of HIV infection and ARVs and prevent issues with adherence [23]. Standard care in a clinic included the doctor, nurse, and social worker providing customary medication adherence education. Medication adherence measured by pharmacy drug refill was significantly better (mean refill score 2.7 in the intervention group and 1.7 in control group, p = 0.002). The intervention group also showed improvement in their knowledge score compared to the control group (p = 0.02) and in their reported adherence although this difference was not statistically significant (p = 0.07).

There were no significant differences in the change in CD4 counts or viral loads either immediately or 6–11 months later. 45% of participants in the intervention group maintained or achieved a viral load, < 2.6 log10copies/ml (<400copies/ml) compared to 24% in the control group. CD4 figures were not reported [23]. This study had a low risk of selection and attrition bias but the small sample size of the study reduces the quality of these results.

Wang (n = 116) provided nurse-delivered home visits combined with telephone calls to HIV-infected heroin users to the intervention group, whilst the control group received routine care involving a monthly clinic visit [28]. Assessment of selection, performance and detection bias was not possible due to lack of reporting of these methodological aspects. There was a low risk of attrition bias and at the end of the eight months, participants in the experimental group were more likely to report taking 100% of pills (Mantel-Haensel 1.57, 95% CI 1.19 to 2.07, reported p = 0.0001) and taking pills on time (Mantel-Haensel 2.50, 95% CI 1.51 to 4.13, reported p = 0.0001) than those in the control group.

Williams 2006 (n = 171) assessed an adherence tool which followed a structured educational model facilitated by a nurse and community support worker conducting home visits, compared to standard care [27]. Adherence was recorded as the ratio of the number of Medication Event Monitoring Systems cap (MEMS cap) openings to number of openings expected if the medication was taken as prescribed. There was a low risk of detection bias, loss to follow-up of 28% and 25% respectively, and allocation concealment was not reported. The median CD4 counts were 345 and 341 for the intervention and control arms respectively. Comparing the proportion of participants with greater than 90% adherence, there was a statistically significant difference between the two arms at 15 months, favouring the intervention group (reported extended Mantel-Hansel test 5.80, p = 0.02). There were no significant changes at 12 and 15 months in proportion of people with CD4 count greater than 200 or undetectable viral loads (actual figures not reported).

Williams 2014 (n = 110) investigated the effects of an adherence intervention, which included home-based social and educational components provided by a nurse and peer educator, compared to standard care adherence clinic support services [29]. A visual analogue scale was used to evaluate adherence to ART over the previous 30 days. There is a risk of attrition bias with differential loss to follow-up of 5% and 22% at 12 months. At baseline all subjects reported taking 90% or less of prescribed medication (pre-ART or ART). In reported bivariate analyses, there was a significant difference in adherence between the two groups at 6 and 12 months (p = 0.003 and p = 0.005). In reported multivariate analyses, controlling for baseline factors, the experimental group had a significantly higher proportion of people who were adherent (p = 0.009). The proportion of those with an undetectable viral load increased in both groups at 6 months (44% in control group, 57% in intervention group) and at 12 months (59% control group, 72% intervention group). But in multivariate analyses controlling for baseline factors, there was no difference between groups (p = 0.18). In reported multivariate analyses CD4 count did not differ by group (p = 0.65) but an overall increase in CD4 count category was seen in all subjects between baseline and 12 months (p = 0.003).

Psychosocial support

Five studies investigated the effects of a home-based programme provided by nurses on psychological wellbeing [24,25,26, 28, 29].

Psychiatric care

Blank (n = 238) examined a home-based advanced practice psychiatric nurse intervention in individuals with serious mental illness and HIV [25]. The nurse provided in-home consultations and co-ordinated medical and mental health services. Growth curve analysis estimating the treatment effects on viral load (log10copies/ml) and Medical Outcomes Study 12-Item Short-Form Health Survey (SF-12) mental health scores, showed that the intervention reduced the rate of change over time in viral load and increased the rate of change over time in SF-12 mental health outcomes. They also compared CD4 percentage and the SF-12 mental health score, showing only significant treatment effect for SF-12 mental health score. A model comparing viral load and SF-12 physical health scores showed a significant decline in viral load but no change in perceptions of physical health status. A model comparing CD4 and SF12 physical health showed no significant change. Therefore, results show significant improvement in health-related quality of life for a mental health subscale but not for a physical health subscale. However, there was a risk of both detection and performance bias.

Hanrahan (n = 238) evaluated a home-based advanced practice psychiatric nurse intervention in individuals with serious mental illness and HIV [26]. The nurse provided in-home consultations and co-ordinated medical and mental health services. Both groups had a reduction in psychiatric symptoms (Colorado Symptom Index (CSI) score) from baseline to 12 months, but the relative difference in these improvements was not significant (reported effect (d) = − 4.03, 95% CI -15.99 to 7.83, p = 0.51). However, during the same period symptoms of depression (PHQ-9 score) significantly decreased in the experimental group compared to the control group, with an average treatment effect of an increased PHQ-9 score of 4.40 (95% CI -2.66 to 11.46, p = 0.2). There was no clear difference in changes in health-related quality of life outcomes (SF-12) over time between groups. In repeated measured random regression models, Group x Time interactions were all non-significant (reported p > 0.05). Allocation concealment was adequate and data collectors were blinded.

Counselling and emotional support

Miles (n = 109) assessed the psychosocial impact of home visits carried out by three registered nurses in the homes of African American women with HIV who were the principal caregivers for one or more children under the age of nine [24]. At six months, there was a statistically significant difference in scores for physical functioning (Medical Outcomes Survey-HIV (MOS-HIV)) (WMD 1.45, 95% CI 0.01 to 2.89), HIV stigma (Demo HIV stigma scale) (WMD -0.25, 95% CI -0.49 to − 0.01) and HIV worry (HIV worry scale) (WMD -0.46, 95% CI -0.89 to − 0.03). For depressive symptoms (Centre for Epidemiological Studies Depression (CESD) scale), mood (Profile of Mood States (POMS)), general health, and overall functioning (MOS-HIV), no statistically significant difference was found. This study however had a high loss to follow up which weakens the quality of results.

Wang (n = 116) examined the effects of nurse-delivered home visits combined with telephone calls on the quality of life of HIV-infected heroin users [28]. The intervention had a significant effect in reducing the symptoms of depression (assessed using Chinese version of Self-rating Depression Scale (SDS)) (MD -11.53, 95% CI -17.74 to − 5.92). Quality of life measures (measured by the Chinese version of WHO Quality of Life) also improved including physical (MD 2.97, 95% CI 1.75 to 4.19), psychological (MD 2.72, 95% CI 1.61 to 3.83), social (MD 2.10, 95% CI 0.78 to 3.42) and environmental (MD 2.40, 95% CI 1.23 to 3.57) domains.

Williams 2014 (n = 110) investigated the effects of nurse-delivered home visits on symptoms of depression (CESD scale), social support (Social Support Rating Scale (SSRS)) and stigma (HIV stigma scale) [29]. At baseline, reported multivariate analyses adjusting for baseline social support, stigma and raw CESD score, showed a significant difference in overall depression scores between the two groups (p = 0.001), with the control group having a higher percentage of people with CESD score ≥ 16. When baseline CESD scores were compared to 12-month CESD scores, they reported a significant decrease in depressive symptoms in the intervention group compared to the control group (p = 0.03). There was also a significant change between the six-month CESD scores and 12-month CESD scores, with an increase in depressive symptoms in control subjects and decrease in intervention subjects (p = 0.05). Baseline raw CESD and baseline stigma were significant predictors of CESD scores (p < 0.001 and p = 0.003 respectively) but not baseline social support.

Discussion

Over the past five years various reviews have assessed community-based care for HIV (Table 6). Interventions have looked at decentralised treatment and use of lay health workers and volunteers. The WHO recommends that nurse-led teams can deliver most interventions including initiating and monitoring ART, managing uncomplicated opportunistic infections and providing primary mental health and neurological care [30]. Our review adds to what is known by focussing on assessing the effects of home-based nursing on morbidity in people with HIV/AIDS.

To minimise publication and indexing bias, we used two authors working independently to select studies, perform data extraction and risk of bias assessments. The review included seven studies, conducted in the USA and China. Included studies were small, conducted mainly in adults. Five trials used adequate methods for generating the allocation sequence [23, 24, 26, 27, 29] and allocation concealment was adequate in two trials [23, 26]. Only one trial reported high losses to follow up [24]. This type of intervention is difficult to blind and only one trial blinded personnel and data collectors [27]. Another limitation is that grey literature was not searched.

Reported adherence to ART improved with nurse-led home-based care. Self-reported adherence measures could be liable to a social desirability bias in which participants felt obliged to report that their adherence was better at the end of the trial because they were aware that this is what the intervention is aiming to achieve. However more objective measures to adherence such as the pharmacy drug refill did also support this. Despite improved adherence to ART, the interventions did not appear to affect biological parameters. Interestingly a review of direct observation in HIV therapy, mostly performed in the community, also reported no effect on virological suppression [31]. Possible reasons for a high viral load despite adherence include drug resistance, treatment failure or an adequate adherence irrespective of the intervention [31]. Another systematic review examining interventions for enhancing adherence to ART also concluded that nurse-led home-based strategies are effective [32].

In terms of psychological support, psychiatric nurse home interventions improved depressive symptoms in those with an existing mental health condition. Other findings for home based psychological support were mixed. Two studies found a reduction in symptoms of depression, whilst another found no difference, but stigma scales and physical functioning were improved. This highlights the potential psychosocial benefits of home-based care but with the self-reported scales, there could also be an element of the social desirability bias mentioned above, particularly as participants were not blinded. Wouters 2012 also found that community-based initiatives providing social support and counselling to people living with HIV could effectively support and improve medical care [9].

None of the included studies looked at improved medical care (Fig. 1). With the current move to test and treat, pre-ART care is now not so relevant but other medical care such as screening for opportunistic infections and co-morbidities and related referral is important. Oni et al. found a high prevalence of multiple morbidities among ART patients aged under 45 years [33]. With the increase in diseases of lifestyle, such as diabetes and hypertension, early identification and management of co-morbidities is also important [33].

Conclusions

The results indicate that nurse led home-based interventions could help adherence to ART. Psychiatric nurse support in those with existing mental health conditions improved mental health and depressive symptoms. Home-based psychological support impacted on HIV stigma, worry and physical functioning and in certain cases depressive symptoms.

However, studies were generally small and conducted in limited geographic areas, limiting the quality of evidence. Further larger scale studies are needed looking in more detail at improving home-based medical care for HIV, for example screening for opportunistic infections and co-morbidities.

Abbreviations

- AIDS:

-

acquired immunodeficiency syndrome

- ART:

-

antiretroviral therapy

- CD4 cell:

-

T helper cell (type of white blood cell) that is a vital part of the human immune system

- CESD:

-

Centre for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale

- CHW:

-

community health worker

- CI:

-

confidence interval

- CNSA:

-

Committee on a National Strategy for AIDS

- DOT:

-

directly observed treatment

- HBC:

-

home-based care

- HIV:

-

human immunodeficiency virus

- LMIC:

-

low and middle income country

- MEMS:

-

Medication Event Monitoring Systems

- MOS-HIV:

-

Medical Outcomes Survey-HIV

- PLWHA:

-

People living with HIV/AIDS

- RCT:

-

randomised controlled trial

- SF-12:

-

Medical Outcomes Study 12-Item Short-Form Health Survey

- WHO:

-

World Health Organisation

- WMD:

-

weighted mean difference

References

UNAIDS: Global Aids update 2016. 2016.

WHO CG: The use of antiretroviral drugs for treating and preventing HIV infection. 2016.

Govindasamy D, Ford N, Kranzer K. Risk factors, barriers and facilitators for linkage to antiretroviral therapy care. AIDS. 2012;26:2059–67.

WHO: Consolidated guidelines on the use of antiretroviral drugs for treating and preventing HIV infection. Recommendations for a public health approach. 2013.

Kredo T, Ford N, Adeniyi FB, Garner P. Decentralising HIV treatment in lower- and middle-income countries. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013;6:CD009987.

Kredo T, Adeniyi FB, Bateganya M, Pienaar ED. Task shifting from doctors to non-doctors for initiation and maintenance of antiretroviral therapy. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014;7:CD007331.

WHO: Community home-based care in resource-limiited settings: a framework for action. 2002.

Uys L. A model for home based care. In Home based HIV/AIDS Care. Edited by Uys L, Cameron S. USA: Oxford University Press; 2003.

Wouters E, Van Damme W, van Rensburg D, Masquillier C, Meulemans H. Impact of community-based support services on antiretroviral treatment programme delivery and outcomes in resource-limited countries: a synthetic review. BMC Health Serv Res. 2012;12:194.

Wringe A, Cataldo F, Stevenson N, Fakoya A. Delivering comprehensive home-based care programmes for HIV: a review of lessons learned and challenges ahead in the era of antiretroviral therapy. Health Policy Plan. 2010;25:352–62.

Waterman H, Griffiths J, Gellard L, O’Keefe C, Olang G, Ayuyo J, Obwanda E, Ogwethe V, Ondiege J. Power brokering, empowering, and educating: the role of home-based care professionals in the reduction of HIV-related stigma in Kenya. Qual Health Res. 2007;17:1028–39.

Frasca K, Cohn J. Integration of HIV and tuberculosis in the community. J Int Assoc Provid AIDS Care. 2014;13(6):534–8.

WHO, PEPFAR, UNAIDS: Treat, train, retain. Task shifting. Global recommendations and guidelines. 2008.

Okwundu CI, Nagpal S, Musekiwa A, Sinclair D. Home- or community-based programmes for treating malaria. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013;

Clark AM, Haykowsky M, Kryworuchko J, MacClure T, Scott J, DesMeules M, Luo W, Liang Y. McAlister F a. A meta-analysis of randomized control trials of home-based secondary prevention programs for coronary artery disease. Eur J Cardiovasc Prev Rehabil. 2010;17:261–70.

Shepperd S, Wee B, Straus SE. Hospital at home: home-based end of life care. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2011;(7):CD009231.

Smeenk FW, van Haastregt JC, de Witte LP, Crebolder HF. Effectiveness of home care programmes for patients with incurable cancer on their quality of life and time spent in hospital: systematic review. BMJ. 1998;316:1939–44.

Lewin S, Munabi-Babigumira S, Glenton C, Daniels K, Bosch-Capblanch X, van Wyk BE, Odgaard-Jensen J, Johansen M, Aja GN, Zwarenstein M, Scheel IB. Lay health workers in primary and community health care for maternal and child health and the management of infectious diseases. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2010;(3):CD004015.

Schneider H, Lehmann U. Lay health workers and HIV programmes: implications for health systems. AIDS Care. 2010;22(Suppl 1):60–7.

Young T, Busgeeth K. Home-based care for reducing morbidity and mortality in people infected with HIV/AIDS. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2010;(1):CD005417.

Bateganya M, Abdulwadud OA, Kiene SM. Home-based HIV voluntary counselling and testing (VCT) for improving uptake of HIV testing. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2010;(7):CD006493.

Modified Directly Observed Antiretroviral Therapy - Full Text View - ClinicalTrials.gov. https://clinicaltrials.gov/show/nct01985269. Accessed Mar 2015.

Berrien VM, Salazar JC, Reynolds E, McKay K. Adherence to antiretroviral therapy in HIV-infected pediatric patients improves with home-based intensive nursing intervention. AIDS Patient Care STDs. 2004;18:355–63.

Miles MS, Holditch-Davis D, Eron J, Black BP, Pedersen C. Harris D a. an HIV self-care symptom management intervention for African American mothers. Nurs Res. 2003;52:350–60.

Blank MB, Hennessy M, Eisenberg MM. Increasing quality of life and reducing HIV burden: the PATH+ intervention. AIDS Behav. 2014;18:716–25.

Hanrahan NP, Wu E, Kelly D, Aiken LH, Blank MB. Randomized clinical trial of the effectiveness of a home-based advanced practice psychiatric nurse intervention: outcomes for individuals with serious mental illness and HIV. Nurs Res Pract. 2011;2011:1–10.

Williams AB, Fennie KP. Bova C a, burgess JD, Danvers K a, Dieckhaus KD. Home visits to improve adherence to highly active antiretroviral therapy: a randomized controlled trial. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2006;42:314–21.

Wang H, Zhou J, Huang L, Li X, Fennie KP, Williams AB. Effects of nurse-delivered home visits combined with telephone calls on medication adherence and quality of life in HIV-infected heroin users in Hunan of China. J Clin Nurs. 2010;19:380–8.

Williams AB, Wang H, Li X, Chen J, Li L, Fennie K: Efficacy of an evidence-based ARV adherence intervention in China. AIDS Patient Care STDs 2014.

WHO: Priority interventions: HIV/AIDS prevention, treatment and care in the health sector. 2010.

Ford N, Nachega JB, Engel ME, Mills EJ. Directly observed antiretroviral therapy: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised clinical trials. Lancet. 2009;374:2064–71.

Mbuagbaw L, Sivaramalingam B, Navarro T, Hobson N, Keepanasseril A, Wilczynski NJ, Haynes BR, Team the PAR. Interventions for enhancing adherence to antiretroviral therapy (ART): a systematic review of high quality studies. AIDS Patient Care STDs. 2015;29:248–66.

Oni T, Youngblood E, Boulle A, Mcgrath N, Wilkinson RJ. Disease multi-morbidity in peri-urban South Africa- a cross sectional study patterns of HIV, TB, and non-communicable disease multi-morbidity in peri-urban South Africa- a cross sectional study; 2015. p. 1–8.

le Roux IM, Tomlinson M, Harwood JM, O’Connor MJ, Worthman CM, Mbewu N, Stewart J, Hartley M, Swendeman D, Comulada WS, Weiss RE, Rotheram-Borus MJ. Outcomes of home visits for pregnant township mothers and their infants in South Africa: a cluster randomised controlled trial. AIDS. October 2012;2013:1461–71.

Nsibande D, Doherty T, Ijumba P, Tomlinson M, Jackson D, Sanders D, Lawn J. Assessment of the uptake of neonatal and young infant referrals by community health workers to public health facilities in an urban informal settlement, KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa. BMC Health Serv Res. 2013;13:47.

Tomlinson M, Doherty T, Ijumba P, Jackson D, Lawn J, Persson LÅ, Lombard C, Sanders D, Daviaud E, Nkonki L, Goga A, Rohde S, Sitrin D, Colvin M, Chopra M. Goodstart: a cluster randomised effectiveness trial of an integrated, community-based package for maternal and newborn care, with prevention of mother-to-child transmission of HIV in a south African township. Trop Med Int Heal. 2014;19:256–66.

Antoni MH, Cruess DG, Cruess S, Lutgendorf S, Kumar M, Ironson G, Klimas N, Fletcher MA, Schneiderman N. Cognitive-behavioral stress management intervention effects on anxiety, 24-hr urinary norepinephrine output, and T-cytotoxic/suppressor cells over time among symptomatic HIV-infected gay men. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2000;68:31–45.

Iwuji CC, Orne-Gliemann J, Tanser F, Boyer S, Lessells RJ, Lert F, Imrie J, Bärnighausen T, Rekacewicz C, Bazin B, Newell M-L, Dabis F. Evaluation of the impact of immediate versus WHO recommendations-guided antiretroviral therapy initiation on HIV incidence: the ANRS 12249 TasP (treatment as prevention) trial in Hlabisa sub-district, KwaZulu-Natal South Africa: study protocol for a clus. Trials. 2013;14:230.

Maharaj SS, Chetty V. Rehabilitation program for the quality of life for individuals on highly active antiretroviral therapy in KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa: a short report. Int J Rehabil Res. 2011;34:360–5.

Promoting Uptake and Retention of Option B+ in Malawi - Full Text View- ClinicalTrials.gov. https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT02005835. Accessed Mar 2017.

Singer P, Levine R, Rothkopf M, Askanazi J. Home parenteral lipids in AIDS: a three-month study. Nutrition. 1997;13:104–9.

Baigis J, Korniewicz DM, Chase G, Butz A, Jacobson D, Wu AW. Effectiveness of a home-based exercise intervention for HIV-infected adults: a randomized trial. J Assoc Nurses AIDS Care. 2002;13:33–45.

Chang LW, Kagaayi J, Nakigozi G, Ssempijja V, Packer AH, Serwadda D, Quinn TC, Gray RH, Bollinger RC, Reynolds SJ. Effect of peer health workers on AIDS care in Rakai, Uganda: a cluster-randomized trial. PLoS One. 2010;5:1–7.

Colford JM, Saha SR, Wade TJ, Wright CC, Vu M, Charles S, Jensen P, Hubbard A, Levy DA, Eisenberg JNS. A pilot randomized, controlled trial of an in-home drinking water intervention among HIV + persons. J Water Health. 2005;3:173–84.

Dolan SE, Frontera W, Librizzi J, Ljungquist K, Juan S, Dorman R, Cole ME, Kanter JR, Grinspoon S. Effects of a supervised home-based aerobic and progressive resistance training regimen in women infected with human immunodeficiency virus: a randomized trial. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166:1225–31.

Flatley-Brennan P. Computer network home care demonstration: a randomized trial in persons living with AIDS. Comput Biol Med. 1998;28:489–508.

Gustafson DH, Hawkins R, Boberg E, Pingree S, Serlin RE, Graziano F, Chan CL. Impact of a patient-centered, computer-based health information/support system. Am J Prev Med. 1999;16:1–9.

Jaffar S, Amuron B, Foster S, Birungi J, Levin J, Namara G, Nabiryo C, Ndembi N, Kyomuhangi R, Opio A, Bunnell R, Tappero JW, Mermin J, Coutinho A, Grosskurth H. Rates of virological failure in patients treated in a home-based versus a facility-based HIV-care model in Jinja, Southeast Uganda: a cluster-randomised equivalence trial. Lancet. 2009;374:2080–9.

León A, Cáceres C, Fernández E, Chausa P, Martin M, Codina C, Rousaud A, Blanch J, Mallolas J, Martinez E, Blanco JL, Laguno M, Larrousse M, Milinkovic A, Zamora L, Canal N, Miró JM, Gatell JM, Gómez EJ, García F. A new multidisciplinary home care telemedicine system to monitor stable chronic human immunodeficiency virus-infected patients: a randomized study. PLoS One. 2011;6(1):e14515.

Lule JR, Mermin J, Ekwaru JP, Malamba S, Downing R, Ransom R, Nakanjako D, Wafula W, Hughes P, Bunnell R, Kaharuza F, Coutinho A, Kigozi A, Quick R. Effect of home-based water chlorination and safe storage on diarrhea among persons with human immunodeficiency virus in Uganda. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2005;73:926–33.

MacPherson P, Lalloo DG, Webb EL, Maheswaran H, Choko AT, Makombe SD, Butterworth AE, van Oosterhout JJ, Desmond N, Thindwa D, Squire SB, Hayes RJ, Corbett EL. Effect of optional home initiation of HIV care following HIV self-testing on antiretroviral therapy initiation among adults in Malawi: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2014;312(4):372–9.

Melchior JC, Chastang C, Gelas P, Carbonnel F, Zazzo JF, Boulier A, Cosnes J, Boulétreau P, Messing B. Efficacy of 2-month total parenteral nutrition in AIDS patients: a controlled randomized prospective trial. The French multicenter total parenteral nutrition cooperative group study. AIDS. 1996;10:379–84.

Muhamadi L, Tumwesigye NM, Kadobera D, Marrone G, Wabwire-Mangen F, Pariyo G, Peterson S, Ekström AM. A single-blind randomized controlled trial to evaluate the effect of extended counseling on uptake of pre-antiretroviral care in eastern Uganda. Trials. 2011;12:184.

Potterton J, Stewart A, Cooper P, Becker P. The effect of a basic home stimulation programme on the development of young children infected with HIV. Dev Med Child Neurol. 2010;52:547–51.

Roos R, Myezwa H, Van AH, Musenge E. Effects of an education and home-based pedometer walking program on ischemic heart disease risk factors in people infected with HIV. A Randomized Trial. 2014;67:268–76.

Selke HM, Kimaiyo S, Sidle JE, Vedanthan R, Tierney WM, Shen C, Denski CD, Katschke AR, Wools-Kaloustian K. Task-shifting of antiretroviral delivery from health care workers to persons living with HIV/AIDS: clinical outcomes of a community-based program in Kenya. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2010;55:483–90.

Cherin DA, Huba GJ, Brief DE, Melchior LA. Evaluation of the Transprofessional model of home health care for HIV/AIDS. Home Health Care Serv Q. 1998;17:55–72.

Nickel JT, Salsberry PJ, Caswell RJ, Keller MD, Long T, O’Connell M. Quality of life in nurse case management of persons with AIDS receiving home care. Res Nurs Health. 1996;19:91–9.

Efficacy of promoting home-based HIV testing with online counseling on increasing HIV testing among men who have sex with men. ChiCTR-PRC-13003310. Chinese Clinical Trial Register. http://www.chictr.org.cn/showprojen.aspx?proj=6249. Accessed Mar 2015.

DallaPiazza M, Aberg JA. HIV counseling and testing for household members of HIV-infected individuals in Africa: should prevention programs focus on home-based rather than clinic-based outreach? Curr HIV/AIDS Rep. 2011;8:75–7.

Doherty T, Tabana H, Jackson D, Naik R, Zembe W, Lombard C, Swanevelder S, Fox MP, Thorson A, Ekström AM, Chopra M. Effect of home based HIV counselling and testing intervention in rural South Africa: cluster randomised trial. BMJ. 2013;346(June):f3481.

Fylkesnes K, Sandøy IF, Jürgensen M, Chipimo PJ, Mwangala S, Michelo C. Strong effects of home-based voluntary HIV counselling and testing on acceptance and equity: a cluster randomised trial in Zambia. Soc Sci Med. 2013;86:9–16.

Jackson D, Naik R, Tabana H, Pillay M, Madurai S, Zembe W, Doherty T. Quality of home-based rapid HIV testing by community lay counsellors in a rural district of South Africa. J Int AIDS Soc. 2013;16:1–4.

Jürgensen M, Sandøy IF, Michelo C, Fylkesnes K, Mwangala S, Blystad A. The seven Cs of the high acceptability of home-based VCT: results from a mixed methods approach in Zambia. Soc Sci Med. 2013;97:210–9.

Jürgensen M, Sandøy IF, Michelo C, Fylkesnes K. Effects of home-based voluntary counselling and testing on HIV-related stigma: findings from a cluster-randomized trial in Zambia. Soc Sci Med. 2013;81:18–25.

Labhardt ND, Motlomelo M, Cerutti B, Pfeiffer K, Kamele M, Hobbins MA, Ehmer J. Home-based versus mobile clinic HIV testing and counseling in rural Lesotho: a cluster-randomized trial. PLoS Med. 2014;11:e1001768.

Low C, Pop-Eleches C, Rono W, Plous E, Kirk A, Ndege S, Goldstein M, Thirumurthy H. The effects of home-based HIV counseling and testing on HIV/AIDS stigma among individuals and community leaders in western Kenya: evidence from a cluster-randomized trial. AIDS Care. 2013;25(Supplement 1):S97.

Lugada E, Levin J, Abang B, Mermin J, Mugalanzi E, Namara G, Gupta S, Grosskurth H, Jaffar S, Coutinho A, Bunnell R. Comparison of home and clinic-based HIV testing among household members of persons taking antiretroviral therapy in Uganda: results from a randomized trial. JAIDS J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2010;55:245–52.

Home-based Partner Education and Testing (HOPE) Study - Full Text View - ClinicalTrials.gov. https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT01784783. Accessed Mar 2015.

Osoti AO, John-Stewart G, Kiarie J, Richardson B, Kinuthia J, Krakowiak D, Farquhar C. Home visits during pregnancy enhance male partner HIV counselling and testing in Kenya: a randomized clinical trial. AIDS. 2014;28(July 2013):95–103.

Batamwita R. Assessment of antiretroviral therapy knowledge and willingness of persons with HIV to support its uptake in Uganda. Patient Prefer Adherence. 2011;5:499.

Brennan PF, Ripich S. Use of a home-care computer network by persons with AIDS. Int J Technol Assess Health Care. 1994;10:258–72.

Byakika-Tusiime J, Crane J, Oyugi JH, Ragland K, Kawuma A, Musoke P, Bangsberg DR. Longitudinal antiretroviral adherence in HIV+ Ugandan parents and their children initiating HAART in the MTCT-plus family treatment model: role of depression in declining adherence over time. AIDS Behav. 2009;13(Suppl 1):82–91.

Choy FN, Wilson DC, Willcox GS, Crocker KS. Experience with home aerosolized pentamidine treatment in patients with AIDS. DICP. 1990;24:592–4.

Di Sorbo PG, Chifamba DD, Mastrojohn J, Sisimayi CN, Williams SH. The Zimbabwe rural palliative care initiative: PCI-Z. J Pain Symptom Manag. 2010;40:19–22.

Holzemer WL, Bakken Henry S, Portillo CJ, Miramontes H. The client adherence profiling-intervention tailoring (CAP-IT) intervention for enhancing adherence to HIV/AIDS medications: a pilot study. J Assoc Nurses AIDS Care. 2000;11:36–44.

Kraak VI. Home-delivered meal programs for homebound people with HIV/AIDS. J Am Diet Assoc. 1995;95:476–81.

Leibowitz A, Iberti T. Home TPN and AIDS patients. J Parenter Enter Nutr. 1992;16:496–7.

Ndekha MJ, Manary MJ, Ashorn P, Briend A. Home-based therapy with ready-to-use therapeutic food is of benefit to malnourished, HIV-infected Malawian children. Acta Paediatr. 2005;94:222–5.

Morales JO, Von Behren L. Secondary bacterial infections in HIV-infected patients: an alternative ambulatory outpatient treatment utilizing intravenous cefotaxime. Am J Med. 1994;97:9–13.

Sandige H, Ndekha MJ, Briend A, Ashorn P, Manary MJ. Home-based treatment of malnourished Malawian children with locally produced or imported ready-to-use food. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2004;39:141–6.

Sjolander JC. Nursing management of the AIDS patient at home. J Enterostomal Ther. 1988;15(4):154–7.

Home-based AIDS Care Project - Full Text View - ClinicalTrials.gov. https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT00119093. Accessed Mar 2015.

Decroo T, Rasschaert F, Telfer B, Remartinez D, Laga M, Ford N. Community-based antiretroviral therapy programs can overcome barriers to retention of patients and decongest health services in sub- saharan africa: a systematic review. Int Health. 2013;5:169–79.

Mw ai GW, Mburu G, Torpey K, Frost P, Ford N, Seeley J. Role and outcomes of community health workers in HIV care in sub-Saharan Africa: a systematic review. J Int AIDS Soc. 2013;16:18586.

Nachega JB, Adetokunboh O, Uthman OA, Knowlton AW, Altice FL, Schechter M, Galárraga O, Geng E, Peltzer K, Chang LW, Van Cutsem G, Jaffar SS, Ford N, Mellins CA, Remien RH, Mills EJ. Community-based interventions to improve and sustain antiretroviral therapy adherence, retention in HIV care and clinical outcomes in low- and middle-income countries for achieving the UNAIDS 90-90-90 targets. Curr HIV/AIDS Rep. 2016;13:241–55.

Rachlis B, Sodhi S, Burciul B, Orbinski J, Cheng AHY, Cole D. A taxonomy for community-based care programs focused on HIV/AIDS prevention, treatment, and care in resource-poor settings. Glob Health Action. 2013;6:1–21.

Acknowledgements

Professor Paul Garner (Liverpool School of Tropical Medicine), for guidance and assistance. Alfred Musekiwa (Centre for Evidence-based Health Care), for advice on data analysis.

Availability of data and material

We included studies which are already in the public domain.

Funding

EMW, TY and TME are partially supported by the Effective Health Care Research Consortium (www.evidence4health.org), which is funded by UK aid for the UK Government for the benefit of developing countries (Grant: 5242). The views expressed do not necessarily reflect UK government policy.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

EMW is corresponding author and guarantor of this manuscript. EMW and TY reviewed the search results and selected potential studies for inclusion. EMW and BZ independently carried out data extraction, formal eligibility and risk of bias assessment. TME assisted with statistical analysis. EMW drafted the manuscript, in conjunction with BZ, TME and TY. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Wood, E.M., Zani, B., Esterhuizen, T.M. et al. Nurse led home-based care for people with HIV/AIDS. BMC Health Serv Res 18, 219 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-018-3002-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-018-3002-4