Abstract

Background

Opinion about euthanasia has been explored among the general population and recently in patients receiving palliative care. 96% of the French population declared themselves in favor of euthanasia while less of 50% of palliative care patients are. The aim of the present study was to explore and identify potential determinant factors associated with favorable or unfavorable opinion about euthanasia in a French population of cancer patients receiving palliative care.

Methods

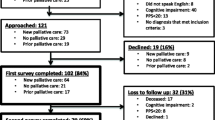

We performed a cross-sectional study among patients in two palliative care units. Eligible patients were identified by the medical staff. Face-to-face interviews were performed by two investigators. Two groups were defined as favorable or unfavorable about euthanasia according to the answer on the specific question about patient opinion on euthanasia. A multivariate analysis including age, belief in God, chemotherapy and gender was built.

Results

Seventy-eight patients were interviewed. Median age was 60.5 years (range: 31–87.2). In univariate analysis, patients with a favorable opinion were most often under 60 years old (62 versus 38% unfavorable; p = 0.035), in couple (64 versus 35%; p = 0.032), didn’t believe in God (72 versus 28% were non-believers; p < 0.001) and had more frequently an history of chemotherapy treatment (58 versus 42% received at least one cycle of chemotherapy; p = 0.005). In a multivariate analysis, age < 60 years, absence of belief in God and an antecedent of chemotherapy were independently associated with a favorable opinion about euthanasia (OR = 0.237 [0.076–0.746]; p = 0.014, OR = 0.143 [0.044–0.469]; p = 0.001, and OR = 10.418 [2.093–51.853]; p = 0.004, respectively).

Conclusion

We report here determinants of opinion about euthanasia in palliative care cancer patients. Thus, young patients who do not believe in God and have a history of chemotherapy treatment are more likely to request the discontinuation or restriction of their treatment. A better understanding of these determinants is essential for the development of information and/or interventions tailored to the palliative context.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Societal issues related to end of life and euthanasia have led to substantial public debate worldwide [1]. In Europe, euthanasia legislation differs from one country to another and is legalized in only three countries [2]. Because of many factors of social, cultural, historical or religious nature, even the definition of euthanasia could be controversial. Based on French law, euthanasia can be defined as “the act of a third party who deliberately ends a person’s life with the intention of putting an end to a situation deemed unbearable” (French National Consultative Committee on Ethics, CCNE, Opinion No. 63, January 2000). In France, the question whether euthanasia should be legalized has been topical for several years. A first law regulated patients’ rights and end-of-life care, called the Leonetti Law [3], after the man who originally proposed the law, in 2005. This law explicitly allows physicians to provide far-reaching symptom control, even at the risk of shortening life, in order to relieve the person’s suffering at an advanced stage of a serious and incurable disease. Thus the concept of double effect was introduced, while prohibiting physician-assisted suicide and euthanasia. It has been suggested that the Leonetti’s law also allows continuous deep sedation as a form of ongoing symptom control [4], although it does not mention the practice. The end of life remains a topic of legal, political and ethical debate in France. After the re-examination by a parliamentary commission of questions related to the accompaniment of patients at the end of life and euthanasia, the French Government voted a new law in February 2016 called the Claeys-Leonetti Law [5], which introduce various significant amendments to the existing Leonetti’s law. This law establishes the right to deep and continuous sedation, consisting of sedative and analgesic treatment leading to a profound and continuous change of vigilance to death if the patient is likely to suffer pain, associated with the cessation of all life-sustaining treatments including artificial nutrition and hydration [6]. Claeys-Leonetti law increased patients’ autonomy by strengthening the value of advance directives and extending the spectrum of unreasonable obstinacy to the sustainment of vital treatments [7]. The law also confirmed the ban on euthanasia per se [5]. However, while 96% of French people have been found to be in favor of euthanasia [8], fewer than 50% of physicians are [9]. We recently explored opinion about euthanasia among patients receiving palliative care [10]. This previous study showed that patients in an end-of-life setting are probably more reticent to legalize euthanasia than general population since only 48% of palliative care patients were favorable to this practice. This reflects a large difference of opinion between the general population, healthy, and patients with a fatal incurable disease such as cancer. The aim of the present study was to explore and identify potential determinants factors associated with favorable or unfavorable opinion about euthanasia in a French population of cancer patients in palliative care units.

Methods

Design and setting

We performed a cross-sectional study among patients in two palliative care units: Timone University Hospital (Marseille, France) and La Maison (Gardanne, France, non-profit association under the terms of the french 1901 law), which is an institution run by a non-profit association providing palliative care. Eligible patients were identified by the medical staff. They were selected after an initial interview with psychologists and a members of the medical team in order to identify anxious or depressed patients and those who would not be physically and/or psychologically able to answer questions during the study interview. Two investigators conduct face-to-face interviews on the two sites alternatively. A translation of the interview questionnaire is available in Additional file 1. Before starting the interview, investigators presented the purpose of the study and the nature of the questions to the patient. The interview did not last longer than 30 min.

Population

Inclusion criteria were as follows: age ≥ 18 years old; locally advanced or metastatic cancer; patient with palliative care (as defined by the French Society of Palliative and Support Care, SFAP, as active care in a global approach to persons with progressive or terminal illness) [6] in a palliative care unit or in specific palliative care beds in non-palliative care units; without sleepiness (Epworth scale: score > 16) [11]; without anxiety and/or mood disorder (HAD scale: score < 7) [12]; and providing written informed consent for participation. Patients already sedated or those unable to communicate or to understand the purpose and conditions of the study (based on the clinician’s judgment) were excluded.

Data collection

Socio-demographic data (age, gender, educational level, professional activity, family situation) and clinical data (chemotherapy yes/no, regardless the number of line or cycle of treatment) were collected from medical records then confirmed during the interview. Pain data was collected during interview (visual analogic pain scale from 0 to 10; 0 no pain, 10 maximal pain expressed as a categorical variable: yes (pain > 3/10) / no (pain ≤3/10) and paroxysmal pain (maximal pain they had felt during their hospitalization) [13]; mention of believing in God (yes/no); a question about the quality of global information they received about their treatments (well-informed: yes/no); a question about support from family and friends (yes/no); a question about whether they had given advance directives (yes/no) and a specific question (yes/no) about their opinion on euthanasia.

Ethics, consent and permission

All procedures performed in this study involving human participants were done in accordance with the French ethical standards and with the 2008 Helsinki declaration. As this was a non-interventional study, ethical approval was not needed, according to French law (Article L1121–1, Law n°2011–2012 29 December 2011 - art. 5). All subjects participated on a voluntary basis. Written consent for participation in the study was obtained from all participants.

Statistical analysis

Categorical variables were described using counts and frequencies and quantitative variables were described using medians and ranges. Two groups were defined as favorable or unfavorable about euthanasia according to the answer on the specific question about patient opinion on euthanasia. Patients’ characteristics were compared with χ2 or exact Fisher’s tests for discrete variables and rank-Wilcoxon’s tests for continuous variables according patient opinion on euthanasia. A multivariate analysis was conducted using logistic regression including variables selected on their clinical interest and/or a threshold p-value ≤0.05 during univariate analysis: age (≤60 vs. > 60 years), belief in God (no vs. yes), chemotherapy (no vs. yes) and gender (female vs. male). Results were expressed as odds ratios and their 95% confidence intervals. The level of statistical significance was set at 1-α = 0.95. Statistical analyses were carried out with the SPSS® software version 17.

Results

Patients

A total of 78 patients were interviewed. Median age was 60.5 years (range 31 to 87.2), 56% were women (n = 44), 40% were in a couple (n = 31) and 54% believed in God (n = 42). The main cancer sites were pulmonary (24%; n = 19), digestive (20%; n = 16), head and neck (14%; n = 11) and gynecologic (13%; n = 10). 79% had already received chemotherapy (n = 62).

Opinion about euthanasia

50% of patients interviewed had a favorable opinion about euthanasia (n = 39).Univariate analysis (Table 1) showed differences between patients with a favorable opinion and those without. Patients with a favorable opinion were most often under 60 years old (62% of patients < 60 years old were favorable versus 38% unfavorable; p = 0.035), in couple (64 versus 35%; p = 0.032), didn’t believe in God (72 versus 28% were non-believers; p < 0.001) and had more frequently an history of chemotherapy treatment (58 versus 42% received at least one cycle of chemotherapy; p = 0.005). Pain level did not statistically impact the opinion about euthanasia despite a tendency, patients with a visual analogic pain scale > 3 seemed less favorable to euthanasia (p = 0.080). Gender, educational degree, information on treatment and redaction of advance directives were not statistically associated with patients’ opinions. In a multivariate analysis (Table 2), age < 60 years and absence of belief in God were independently associated with a favorable opinion about euthanasia (OR = 0.237 [0.076–0.746]; p = 0.014 and OR = 0.143 [0.044–0.469]; p = 0.001 respectively). Absence of previous use of cytotoxic chemotherapy was independently associated with an unfavorable opinion about euthanasia (OR = 10.418 [2.093–51.853]; p = 0.004).

Discussion

While 96% of French people have been found to be in favor of euthanasia, our previous study showed that palliative care patients, like physicians, are more reluctant to legalize euthanasia than the general population [8]. To further understand this area, factors associated with opinions regarding euthanasia seems to be a key issue. Other authors have instigated attitudes of patients with advanced cancer towards euthanasia and/or living wills but did not report any determinants factors associated with favorable or unfavorable opinion [14,15,16]. To the best of our knowledge, our study is the first identifying determinants associated with favorable or unfavorable opinion about euthanasia in cancer patients receiving palliative care. Having a favorable opinion about euthanasia was independently associated with an age under 60 years, the lack of belief in God and an antecedent of chemotherapy treatment. The impact of young age is in contradiction with the data of De Vleminck A et al. [17] in general population. In a Belgian cohort, they report an association between age > 55 years and making advance directives about euthanasia. Moreover, the euthanasia registration documents compiled between 1 January 2008 and 31 December 2009 and examined by the Federal Commission for the Control and Evaluation of Euthanasia in Belgium showed that half of the acts of euthanasia performed concerned patients between 60 and 79 years old [18]. Religions may regard understanding death and dying as vital to finding meaning in human life [19]. So it’s not surprising that all faiths have strong views on euthanasia and that believer are more reluctant to it. Indeed, the independent effect of religiosity has been extensively discussed in previous studies in general population [20, 21]. Other study showed that stronger religious belief was associated with more positive support for euthanasia [22]. However, the measures used to assess religiosity in these studies were not the same and again, general population was considered. Nevertheless, “to believe in God” is a rather simplistic way to explore religiosity and spirituality and their impact upon wish to hasten death and euthanasia. Some authors built a religiosity index including different items [23]. Other studies used more specific questions as the “religious affiliation” [24], the “belief in the church’s teachings” [25], or the “attendance to religious services” [26]. The third independent factor associated with a favorable opinion was the antecedent of cytotoxic chemotherapy treatment. Unfortunately, we did not have access to data on tolerance and toxicity assessments during the cytotoxic treatment due to the multiple centers involved in the treatment of patients prior to their arrival in the palliative care unit. This information could have helped in the interpretation of this data. However, we can make some assumptions. The succession of drug treatments of these patients may have trivialized the interventionism of doctors and cause patient lassitude. Moreover the patient has been confronted with announcements of therapeutic failures thereby placing him in a position where he may feel neglected, Unlike patients for whom exclusive palliative care has been undertaken from the outset and would be well perceived as active.

Family situation had a statistical impact on opinion about euthanasia only in univariate analysis. An explanation for this may be that patients living in a couple might not want to be a burden for their partner by undergoing protracted agony. However, another explanation may be found in a study of the Austrian population in which W.J. Stronegger [27] found less rejection of active euthanasia among couples and people with children. Another finding was that information given by medical staff about the treatment did not influence our patients’ opinion about euthanasia. This could be a bias because most of patients in palliative care are generally well informed about their treatment, its side-effects and the possibility of improving the last moments of their life. In addition, educational level is probably responsible for a different representation of euthanasia but did not influence significantly our patients’ opinion about it. Furthermore, level of pain was not associated with adhesion to euthanasia. This finding is in contradiction to another study that found, albeit in a very small number of patients, one of the principal reasons for requesting euthanasia was fear of future pain [28].

Our study has some limitations, lying mainly in the sample size and in the simplification of the questionnaire imposed by the context of patient vulnerability at the end of life. We arbitrary decided to consider the euthanasia opinion as a binary variable. Amount of information that patients wanted to share with us could be impacted by the idea they had about our own point of view on euthanasia. However, this approach was already used in similar works [26, 29] and leads to easier interpretation and presentation of results. Although investigating a wish to hasten death and opinions regarding euthanasia is of interest to for the development of information and/or interventions tailored to the palliative context, it poses considerable difficulties in terms of research. It raises questions about our current ability to care for and accompany patients through this most difficult of life stages. Medical advances, which have transformed diseases that once led to a quick death into chronic illnesses, coupled with increased life expectancy and other social phenomena linked to development, make it likely that far from being eradicated these situations will become more common [30]. The main contribution of this study is to demonstrate the feasibility of broaching sensitive issues such as euthanasia and cessation of care with patients in vulnerable situations. Based on this, we are currently conducting a national multicenter prospective study aimed to interview a thousand patients about the various points covered in the Cleays-Leonetti law, in order to minimize biases but also exploring a greater number of variables. We hope that our findings will be taken into account by lawmakers in France in order to satisfy the wishes of patients as well as possible.

Conclusions

The present study reports determinants of opinion about euthanasia in palliative care cancer patients. Thus, young patients who do not believe in God and who have a history of chemotherapy are more likely to request the discontinuation or restriction of their treatment. A better understanding of these determinants is essential for the development of information and/or interventions tailored to the palliative context.

References

Ferrand E, Rondeau E, Lemaire F, Fischler M. Requests for euthanasia and palliative care in France. Lancet Lond Engl. 2011;377:467–8.

Emanuel EJ, Onwuteaka-Philipsen BD, Urwin JW, Cohen J. Attitudes and practices of euthanasia and physician-assisted suicide in the United States, Canada, and Europe. JAMA. 2016;316:79–90.

LOI n° 2005–370 du 22 avril 2005 relative aux droits des malades et à la fin de vie. 2005. https://www.legifrance.gouv.fr/affichTexte.do?cidTexte=JORFTEXT000000446240&categorieLien=id.

Raus K, Chambaere K, Sterckx S. Controversies surrounding continuous deep sedation at the end of life: the parliamentary and societal debates in France. BMC Med Ethics. 2016;17 https://doi.org/10.1186/s12910-016-0116-2.

LOI n° 2016–87 du 2 février 2016 créant de nouveaux droits en faveur des malades et des personnes en fin de vie. 2016.

de Nonneville A, Marin A, Chabal T, Tuzzolino V, Fichaux M, Salas S. End-of-life practices in France under the Claeys-Leonetti law: report of three cases in the oncology unit. Case Rep Oncol. 2016;9:650–4.

Boulanger A. Les directives anticipées et le désir de maîtrise de sa fin de vie. Médecine Droit. 2017;2017:136–40.

IFOP - Le regard des Français sur la fin de vie. 2014. https://www.admd.net/sites/default/files/2017-01/Ifop%20Admd%20-%20avril%202015.pdf.

Dany L, Baumstarck K, Dudoit E, Duffaud F, Auquier P, Salas S. Determinants of favourable opinions about euthanasia in a sample of French physicians. BMC Palliat Care. 2015;14:59.

Boulanger A, Chabal T, Fichaux M, Destandau M, La Piana JM, Auquier P, et al. Opinions about the new law on end-of-life issues in a sample of french patients receiving palliative care. BMC Palliat Care. 2017;16 https://doi.org/10.1186/s12904-016-0174-8.

Mw J. A new method for measuring daytime sleepiness: the Epworth sleepiness scale. Sleep. 1991;14:540–5.

Zigmond AS, Snaith RP. The hospital anxiety and depression scale. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1983;67:361–70.

Price DD, McGrath PA, Rafii A, Buckingham B. The validation of visual analogue scales as ratio scale measures for chronic and experimental pain. Pain. 1983;17:45–56.

Suarez-Almazor ME, Newman C, Hanson J, Bruera E. Attitudes of terminally ill cancer patients about euthanasia and assisted suicide: predominance of psychosocial determinants and beliefs over symptom distress and subsequent survival. J Clin Oncol Off J Am Soc Clin Oncol. 2002;20:2134–41.

Wilson KG, Chochinov HM, McPherson CJ, Skirko MG, Allard P, Chary S, et al. Desire for euthanasia or physician-assisted suicide in palliative cancer care. Health Psychol Off J Div Health Psychol Am Psychol Assoc. 2007;26:314–23.

Mercadante S, Costanzi A, Marchetti P, Casuccio A. Attitudes among patients with advanced Cancer toward euthanasia and living wills. J Pain Symptom Manag. 2016;51:e3–6.

De Vleminck A, Pardon K, Houttekier D, Van den Block L, Vander Stichele R, Deliens L. The prevalence in the general population of advance directives on euthanasia and discussion of end-of-life wishes: a nationwide survey. BMC Palliat Care. 2015;14:71.

Commission fédérale de contrôle et d’évaluation de l’euthanasie, available on: http://www.ieb-eib.org/fr/pdf/rapport-euthanasie.pdf

Krok D. The role of meaning in life within the relations of religious coping and psychological well-being. J Relig Health. 2015;54:2292–308.

Caddell DP, Euthanasia NRR. American attitudes toward the physician’s role Soc Sci Med 1982. 1995;40:1671–81.

MacDonald WL. Situational factors and attitudes toward voluntary euthanasia. Soc Sci Med 1982. 1998;46:73–81.

Hains C-AM, Hulbert-Williams NJ. Attitudes toward euthanasia and physician-assisted suicide: a study of the multivariate effects of healthcare training, patient characteristics, religion and locus of control. J Med Ethics. 2013;39:713–6.

Verbakel E, Jaspers E. A comparative study on permissiveness toward EuthanasiaReligiosity, slippery slope, autonomy, and death with dignity. Public Opin Q. 2010;74:109–39.

Lavoie M, Godin G, Vézina-Im L-A, Blondeau D, Martineau I, Roy L. Psychosocial determinants of physicians’ intention to practice euthanasia in palliative care. BMC Med Ethics. 2015;16:6.

Parpa E, Mystakidou K, Tsilika E, Sakkas P, Patiraki E, Pistevou-Gombaki K, et al. Attitudes of health care professionals, relatives of advanced cancer patients and public towards euthanasia and physician assisted suicide. Health Policy. 2010;97:160–5.

Peretti-Watel P, Bendiane MK, Moatti JP. Attitudes toward palliative care, conceptions of euthanasia and opinions about its legalization among French physicians. Soc Sci Med 1982. 2005;60:1781–93.

Stronegger WJ, Burkert NT, Grossschädl F, Freidl W. Factors associated with the rejection of active euthanasia: a survey among the general public in Austria. BMC Med Ethics. 2013;14:26.

Johansen S, Hølen JC, Kaasa S, Loge HJ, Materstvedt LJ. Attitudes towards, and wishes for, euthanasia in advanced cancer patients at a palliative medicine unit. Palliat Med. 2005;19:454–60.

Peretti-Watel P, Bendiane MK, Pegliasco H, Lapiana JM, Favre R, Galinier A, et al. Doctors’ opinions on euthanasia, end of life care, and doctor-patient communication: telephone survey in France. BMJ. 2003;327:595–6.

Monforte-Royo C, Villavicencio-Chávez C, Tomás-Sábado J, Balaguer A. The wish to hasten death: a review of clinical studies. Psychooncology. 2011;20:795–804.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to R. Cooke for editing the English. The patient advocacy group “Fondation de France” is also thanked for their support.

Funding

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Availability of data and materials

Socio-demographic and clinical data from patients included in this study were collected from medical records and confirmed during the interview. The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Study concepts: AN, TC, AM, JMP, MF, VT, FD, PA, AB, KB and SS.

Study design: AN, TC and SS.

Data acquisition: AN, TC, AB and SS.

Statistical analysis: AN, TC and SS.

Data interpretation: AN, TC, AM, JMP, MF, VT, FD, PA, AB, KB and SS.

Manuscript editing: AN, TC and SS.

Manuscript review: AN, TC, AM, JMP, MF, VT, FD, PA, AB, KB and SS.

All authors approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

All procedures performed in this study involving human participants were done in accordance with the French ethical standards and with the 2008 Helsinki declaration. As this was a non-interventional study, ethical approval was not needed, according to French law (Article L1121–1, Law n°2011–2012 29 December 2011 - art. 5). All subjects participated on a voluntary basis. Written consent for participation in the study was obtained from all participants.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Additional file

Additional file 1:

Translation of the interview questionnaire. (DOCX 17 kb)

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

de Nonneville, A., Chabal, T., Marin, A. et al. Determinants of favorable or unfavorable opinion about euthanasia in a sample of French cancer patients receiving palliative care. BMC Palliat Care 17, 104 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12904-018-0357-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12904-018-0357-6