Abstract

Background

Socioeconomic inequalities are associated with oral health status, either subjectively (self-rated oral health) or objectively (clinically-diagnosed dental diseases). The aim of this study is to compare the magnitude of socioeconomic inequality in oral health and dental disease among adults in Australia, Canada, New Zealand and the United States (US).

Methods

Nationally-representative survey examination data were used to calculate adjusted absolute differences (AD) in prevalence of untreated decay and fair/poor self-rated oral health (SROH) in income and education. We pooled age- and gender-adjusted inequality estimates using random effects meta-analysis.

Results

New Zealand demonstrated the highest adjusted estimate for untreated decay; the US showed the highest adjusted prevalence of fair/poor SROH. The meta-analysis showed little heterogeneity across countries for the prevalence of decayed teeth; the pooled ADs were 19.7 (95% CI = 16.7–22.7) and 12.0 (95% CI = 8.4–15.7) between highest and lowest education and income groups, respectively. There was heterogeneity in the mean number of decayed teeth and in fair/poor SROH. New Zealand had the widest inequality in decay (education AD = 0.8; 95% CI = 0.4–1.2; income AD = 1.0; 95% CI = 0.5–1.5) and the US the widest inequality in fair/poor SROH (education AD = 40.4; 95% CI = 35.2–45.5; income AD = 20.5; 95% CI = 13.0–27.9).

Conclusions

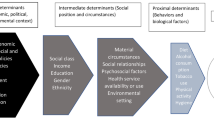

The differences in estimates, and variation in the magnitude of inequality, suggest the need for further examining socio-cultural and contextual determinants of oral health and dental disease in both the included and other countries.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Socioeconomic status has long held interest for its effect on general and oral health. Most evidence indicates that socioeconomic inequalities are associated with oral health status, whether subjectively (self-rated oral health) or objectively (clinically-diagnosed dental diseases) determined [1,2,3,4]. Monitoring social inequalities in oral health is important to provide information on population differences in oral health care needs, preventive practices and oral health system priorities.

Previous studies have demonstrated that socioeconomic position is negatively associated with oral health and dental disease [3, 5], which means the higher the socioeconomic position, the better the perception of oral health and the less experience of clinically-diagnosed dental diseases. Education and income are the most common and relevant indicators used in epidemiology for socioeconomic status measurement [3,4,5,6,7]. Oral health, as a significant constituent of general health, relies on subjective perceptions, whereas disease measurement uses objective clinical indicators [1, 2].

Most previous studies estimated the association between socioeconomic and oral health status based on national surveys or on a specific population [5, 7,8,9,10]. Population determinants of health and disease are more likely to vary across countries than within countries, but it is impossible to generalize the strength and direction of associations across populations and time [11]. Therefore, a global approach is considered fundamental to ‘public health epidemiology’ because it allows identification of international patterns that lead to hypothesis generation, essential to scientific progress [11]. In addition, these studies generally estimated the association by using only one socioeconomic factor with clinical indicators of dental disease. Few studies have tackled both subjective (health) and objective or normative (disease) aspects [12]. Some have focused on low to middle income countries, with few cross-national comparisons [13,14,15,16,17,18]. Hence, the aim of this paper is to compare the magnitude of socioeconomic inequality in oral health and dental disease using representative datasets of adults in Australia, Canada, New Zealand and the United States.

Methods

Comparable high-income countries with dental health care delivery for the adult population based largely on fee-for-service [19, 20] were selected on the availability of nationally-representative survey examination data within a 5 year timeframe. The sources of data were: (1) Australia’s National Survey of Adult Oral Health (NSAOH), conducted between 2004 and 2006 [21]; (2) the Canadian Health Measures Survey (CHMS) that was conducted between 2007 and 2009 [22]; (3) the New Zealand Oral Health Survey (NZOHS) that was conducted from February to December 2009 [23] and; (4) the 2003–2004 module of the US National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) [24]. All surveys included a comprehensive oral examination and detailed demographic and socioeconomic position data.

The NSAOH used a three-stage, stratified clustered design, with 14,123 adults aged 15 years and older taking part in a telephone interview. Of these, 5,505 respondents were invited for, and accepted, a dental examination [21]. The CHMS used a multi-stage stratified sampling design to interview and examine a total of 5,586 participants, including both children and adults [22]. The NZOHS examined 3,196 children and adults. The study base were participants in the previous New Zealand 2006/2007 health survey who agreed to be contacted for future surveys; this second survey was still found to be representative [23]. NHANES, a stratified multistage probability sample of the civilian non-institutionalized population of the US, examined 7,072 people [24].

The response rates for each survey were 49.0% (the interview participation rate) and 43.7% (the examination rate) (NSAOH) [21]; 69.9% of the selected households and among households, 88.3% and 84.9% of individuals (questionnaire and clinic component, respectively) (CHMS) [22], 41.0% (NZOHS) and 79% (interview) and 76% (examination) (NHANES) [25].

In this study, health was captured through the variable self-rated oral health, an indicator of subjective oral health status. In the NSAOH, the self-rated question read: “How would you rate your own dental health?” In the CHMS, the question used was “In general, would you say the health of your mouth is…” The NZOHS asked “How would you describe the health of your teeth or mouth?” In NHANES, the question was “How would you describe the condition of your teeth?” All surveys used the following ordinal response options: ‘Excellent’, ‘Very good’, ‘Good’, ‘Fair’ or ‘Poor’. The responses were dichotomized into ‘excellent, very good or good’ and ‘fair or poor’. Disease was assessed through clinical examination by registered and calibrated dental examiners by using a standard oral epidemiological method /the examination protocol - the U.S. National Institute of Dental Research (National Institute of Dental Research 1987) [26], as untreated tooth decay (% DT > 0) and the mean number of decayed teeth (mean DT). All analyses were based on 28 teeth, excluding third molars.

We used education and income as measures of socioeconomic position. Education was grouped into 4 comparable categories across the surveys (primary, secondary, post-secondary and University). We grouped income categories for each country by quantiles into equal thirds (low, medium, high). However, when converting the categories of income from the survey into tertiles, the resulting proportions were not exactly equal because of prior categorization in the original data collected in each survey.

We limited the analysis to adults aged 25 years and older in order to have a more stable measure of final educational attainment. We calculated absolute differences in prevalence (AD) to examine socioeconomic inequalities and we estimated pooled measures of inequality estimates using random effects meta-analysis.

All analyses were age and gender adjusted to the average covariate distribution of the four surveys combined. In addition, to make population inferences, we utilized survey weights to account for individual probabilities of selection and complex survey designs [21,22,23,24]. We used Stata statistical software (version 13.1) for all analyses [27].

Results

The combined study sample included 14,960 participants, of whom 33.9% were from Australia, 21.9% from Canada, 13.6% from New Zealand and 30.5% from the United States. Table 1 indicates that, across all countries, a slightly higher proportion of females were represented, with the mean population age ranging between 47.9 years for Canada and 49.5 years for Australia. In Australia, a greater proportion of individuals had a University educational level; in Canada, New Zealand and the United States, there was a greater proportion with post-secondary education. Australia also had the highest proportion of individuals with only primary education, and Canada the lowest.

Table 2 shows differences in prevalence and mean estimates among countries; for example, the prevalence of decayed teeth for highly educated New Zealanders was equal to that of the lowest educated group in the United States. The same was observed in the mean number of teeth with untreated decay. Downward gradients by educational level and income within countries favored the more socially advantaged socioeconomic groups. Australia showed a clear gradient in the adjusted estimate for the two disease measures (% DT > 0 and Mean DT) but it is less obvious for fair/poor self-rated oral health. Canada presents a gradient in the proportion of individuals with at least one untreated decayed tooth. New Zealand shows educational gradients in the proportion with untreated decay and fair/poor self-rated oral health. The apparent inconsistency in educational gradients for Canada and New Zealand in disease severity (mean DT) was minor and is likely explained by sampling variability. The United States consistently showed gradients that favor the most highly educated. By income, all countries present gradients for all measures in which lower income groups are more heavily burdened with poorer oral health.

As indicated by the adjusted absolute differences in Table 2, the greatest absolute inequalities between the extreme levels of education (Primary versus University) were in Canada for the proportion of individuals with untreated decay (AD = 22.1), in New Zealand for the mean number of untreated decayed teeth (AD = 0.8), and in the United States for fair/poor self-rated oral health (AD = 40.4). Also, shown in Table 2, the greatest absolute inequality in outcomes between extreme levels of income (Low versus High) is in New Zealand for the proportion with untreated decay (AD = 17.5) and the mean number of untreated decayed teeth (AD = 0.99), whereas, for fair or poor self-rated oral health, the greatest gap is in the United States (AD = 20.5).

Figure 1 presents meta-analysis estimates for educational inequality. The findings on educational inequality for the proportion of individuals with at least one tooth with untreated decay indicate that all variability in the effect sizes is attributable to sampling error (I2 = 0.0%); results for this measure may be considered to be essentially homogenous, with a pooled adjusted AD of 19.7. There was moderate heterogeneity (I2 = 57.5%) for the mean number of untreated decayed teeth; that is, roughly half of the variability was among countries and half of the variability was within countries. New Zealand had the widest absolute socioeconomic inequality (AD = 0.8) and the United States had the narrowest (AD = 0.4). For fair or poor self-rated oral health, the United States had the widest inequality gap (AD = 40.4) and Australia the narrowest (AD = 10.9) with almost all of the variation occurring across countries (I2 = 97.1%).

The meta-analysis for income inequality (Fig. 2) indicates modest heterogeneity across countries in the pooled estimate for the prevalence of untreated decayed teeth (I2 = 29.3%), with New Zealand having the widest gap and the United States the narrowest (AD = 17.5 and 8.9, respectively). The other measure of dental disease ─ the mean number of teeth with untreated decay ─ showed more profound heterogeneity of effect estimates (I2 = 76.4%). Again, New Zealand presented the greatest magnitude of absolute inequality (AD = 0.99), translating into a clinical difference of one tooth, and the United States presented the lowest magnitude of effect (AD = 0.22). There was low heterogeneity in the measure of fair/poor self-rated oral health, with a pooled adjusted absolute difference of 15.8 percentage points, ranging from 13.9 for Australia to 20.5 for the United States.

Discussion

The findings demonstrate socioeconomic inequality in self-rated oral health and untreated dental caries among adults in Australia, Canada, New Zealand and the United States, yet they also highlight some important differences across countries. While New Zealand had the highest absolute inequality in measures of disease, the United States had the highest gaps in perceptions of oral health.

Measures of health status based solely on the objective assessment of pathological abnormality do not include non-biological aspects of health such as the mental and social wellbeing of individuals. We represented disease through normative clinical measures of untreated tooth decay and the magnitude or extent of the disease through the mean number of decayed teeth. To measure oral health, we used self-rated health, considered as “the most feasible, most inclusive and most informative measure of health status” [28].

Interestingly, our findings indicate that New Zealand had greater disease and wider socioeconomic gaps in the proportion and mean number of untreated decay than the other countries, despite having arguably the most comprehensive, wide ranging and free public dental service in the world, that is available to all aged below 18 years (through the School Dental Service). A possible explanation may lie in New Zealand not having a means-tested public dental service for low-income adults (those aged 18+ years), whereas such services are available in Canada, Australia and, to some extent, the United States.

Our study did not examine the effects of other contributing factors such as water fluoridation. It is estimated that 79% of the Australian population, 53% of the New Zealand population, 42% of Canadian population and 60% of the US population is supplied with artificially fluoridated water [29]. Water fluoridation has been regarded as the most effective way to reduce the prevalence and severity of caries, as well as socioeconomic disparities in its occurrence [30]. Although a side-effect of water fluoridation is mild fluorosis of enamel, manifesting a slightly more opaque enamel that is generally perceived by lay people as being aesthetically better, with concomitant effects on their self-rated oral health [31].

The United States had the most unfavorable indicators of oral health, in terms of self-ratings, which is in sharp contrast with self-ratings of general health, in which Americans perform relatively well [32]. In global health measures, the intrinsic value individuals assign to health is driven by a multitude of factors including socio-cultural environments and personal experiences [33].

Dissatisfaction with dental appearance is associated with tooth alignment and crowding, fractures in anterior teeth, and discrepancies in tooth shade [34,35,36]. It relates respectively to orthodontic treatment, aesthetic restorations and tooth bleaching [34, 35, 37]. Oro-facial aesthetics and appearance have been shown to be associated with self-ratings of oral health in diverse population samples [36, 38,39,40,41]. It is possible that the contemporary emphasis on dental aesthetics (such as tooth whitening) contributes to a general dissatisfaction in dental appearance and hence poorer self-rated oral health, whereas the same does not occur for general health.

Differences in reporting may arise from cultural perceptions of health, differences in health expectations and adaptability to ill-health, but also from the way in which the ordinal scale is understood by different individuals and how they weigh the different factors involved in the global measure [42, 43]. In this study, the wording of the SROH question varied slightly among the countries, with NSAOH and NHANES asking specifically about dental health/teeth, Canada framed the question in terms of health of the mouth and New Zealand asked for the health of both the teeth and mouth. Also noteworthy is that the United States asked about the ‘condition’ of the teeth, whereas all other countries framed the question around ‘health’, which could influence how the question is interpreted and may aid in explaining the large difference between the United States and the other countries. A limitation of the study was the inability to measure the extent to which the differences in terminology influenced the findings.

Differences in self-reports may be explained in terms of optimism, such as the ability among older people to adapt to slow declining health, and higher expectations when more socially advantaged groups, for example, report poorer health states [44]. Rousseau and colleagues [45] reported as such, arguing that the complete loss of all teeth is considered by middle-class people to be far more catastrophic than it is by working-class people, because of differing social norms. It is also possible that the frame of reference through which societies in a given country view disease differs; for example, Australians had the lowest levels of self-rated fair or poor health yet their levels of disease were as high as or higher than disease in the United States. Even subtle differences in subjective ratings point towards cultural, social and psychosocial influences on oral health [46]. Given the cultural and context-specific nature of self-rated health, our findings cannot necessarily be generalized to countries beyond those included in the analysis, and caution needs to be taken when making international comparisons [28, 33].

The study explored two socioeconomic indicators to draw a clear picture of social inequalities. Education has the potential to translate into employment opportunities, receptiveness to health messages and the ability to navigate health care systems, as well as representing values, beliefs, and attitudes. It captures the long-term effects of early life conditions and adult resources on health [47]. Income, which measures material resources and living standards, has a cumulative effect over the life course yet is dynamic in the short-term and may be prone to reverse causality if deteriorating health contributes to changes in income [47].

Whereas educational gradients in oral health and disease show some inconsistencies among countries, income shows consistently clear gradients across all countries. In terms of dental disease, this reflects the ability to access oral health care, favoring populations with higher income. In terms of perceived oral health, those with lower incomes reported lower self-ratings. If this general dissatisfaction were to lead to lower self-ratings than warranted by ‘objective’ health, and higher social groups were to systematically report better health than justified, such differences could lead to overestimates of health inequities [43]. Our study did not explore such possibilities at the individual level, but, on average, socially advantaged groups had better oral health, indicating that such overestimation is unlikely.

The limitations of the study were:

(1) there was no overlap of time period for all four surveys, although it is unlikely inequality estimates would differ systematically as major changes in chronic dental diseases are not expected within short time frames; and (2) Missing data for each survey could affect the findings; however, analyses of bias due to survey non-response was carried out independently, at least in the NSAOH, [21] indicating estimates are unlikely to be affected by systematic error. In addition we used weighted data to account for sampling probabilities and adjusted for age and gender.

An important next step is to compare socio-cultural and health system characteristics that shape disease and health status measures among different countries in order to have a better understanding of the roles these factors and other social determinants play in population oral health.

Conclusion

Our findings demonstrate differences in oral health and dental disease experience across income and education groups, with socioeconomic gradients for both clinically determined and self-reported indicators. Individuals from lower income and education groups consistently experienced higher burdens of untreated dental decay and poorer self-rated oral health. Differences in outcome estimates within countries also indicate conceptual differences between health and disease. The variation in the magnitude of inequality across countries suggests the need for further understanding socio-cultural and contextual determinants of oral health and dental disease.

Abbreviations

- AD:

-

Absolute differences

- CHMS:

-

The Canadian Health Measures Survey

- DT:

-

Decayed teeth

- NHANES:

-

The US National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey

- NSAOH:

-

Australia’s National Survey of Adult Oral Health

- NZOHS:

-

The New Zealand Oral Health Survey

- SROH:

-

Self-rated oral health

- US:

-

The United States

References

Locker D, Slade G. Association between clinical and subjective indicators of oral health status in an older adult population. Gerontology. 1994;11:108–14.

Bowling A. Concepts of functioning, health, well-being and quality of life. In: Measuring health. A review of quality of life measurement scales. 3rd ed. Maidenhead: Open University Press; 2005. p. 1–9.

Tsakos G, Demakakos P, Breeze E, Watt RG. Social gradients in oral health in older adults: findings from the English longitudinal survey of aging. Am J Public Health. 2011;101:1892–9.

Watson CA, Nilam S. Educational level as a social determinant of health and its relationship to periodontal disease as a health outcome. J Dent Sci Ther. 2017;1:8–11.

Mejia G, Jamieson LM, Ha D, Spencer AJ. Greater inequalities in dental treatment than in disease experience. J Dent Res. 2014;93:966–71.

Steele J, Shen J, Tsakos G, Fuller E, Morris S, Watt R, et al. The Interplay between socioeconomic inequalities and clinical oral health. J Dent Res. 2015;94:19–26.

Borrell LN, Burt BA, Neighbors HW, Taylor GW. Social factors and periodontitis in an older population. Am J Public Health. 2004;94:748–54.

Tsakos G, Sheiham A, Iliffe S, Kharicha K, Harari D, Swift CG, et al. The impact of educational level on oral health-related quality of life in older people in London. Eur J Oral Sci. 2009;117:286–92.

Sabbah W, Tsakos G, Sheiham A, Watt RG. The role of health-related behaviors in the socioeconomic disparities in oral health. Soc Sci Med. 2009;68:298–303.

Moradi G, Moinafshar A, Adabi H, Sharafi M, Mostafavi F, Bolbanabad AM. Socioeconomic inequalities in the oral health of people aged 15-40 years in Kurdistan, Iran in 2015: a cross-sectional study. J Prev Med Public Health. 2017;50:303–10.

Pearce N. Global epidemiology: the importance of international comparisons and collaborations. OA Epidemiology. 2013;1:15.

Takagi D, Watanabe Y, Edahiro A, Ohara Y, Murakami M, Murakami K, et al. Factors affecting masticatory function of community-dwelling older people: investigation of the differences in the relevant factors for subjective and objective assessment. Gerodontology. 2017;34:357–64.

Bhandari B, Newton JT, Bernabé E. Social inequalities in adult oral health in 40 low- and middle-income countries. Int Dent J. 2016;66:295–303.

Shen J, Listl S. Investigating social inequalities in older adults’ dentition and the role of dental service use in 14 European countries. Eur J Health Econ. 2016. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10198-016-0866-2.

Elani HW, Harper S, Allison PJ, Bedos C, Kaufman JS. Socio-economic inequalities and Oral health in Canada and the United States. J Dent Res. 2012;91:865–70.

Peres MA, Luzzi L, Peres KG, Sabbah W, Antunes JL, Do LG. Income-related inequalities in inadequate dentition over time in Australia, Brazil and USA adults. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 2015;43:217–25.

Sanders AE, Slade GD, John MT, Steele JG, Suominen-Taipale AL, Lahti S, et al. A cross-national comparison of income gradients in oral health quality of life in four welfare states: application of the Korpi and Palme typology. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2009;63:569–74.

He S, Thomson WM. An oral epidemiological comparison of Chinese and New Zealand adults in 2 key age groups. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 2018;46:154–60.

Downer MC, Drugan CS, Blinkhorn AS. Salaried services in the delivery of dental care in Western industrialised countries: implications for the National Health Service in England. Int Dent J. 2006;56:7–16.

Ju X, Brennan DS, Spencer AJ, Teusner DN. Longitudinal change in dental visits provided by Australian dentists. J Public Health Dent. 2016;76:30–7.

Slade GD, Spencer AJ, Roberts-Thomson KD. Australia’s dental generations. the National Survey of Adult Oral Health 2004–06. AIHW cat. No. DEN 165. Canberra: Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (Dental Statistics and Research Series No. 34); 2007. https://www.adelaide.edu.au/arcpoh/downloads/publications/reports/dental-statistics-research-series/nsaoh-report.pdf

Health Canada. Report on the findings of the oral health component of the Canadian Health Measures Survey 2007–2009. HC Pub.:100183. Ottawa: Publications Health Canada; 2010. http://publications.gc.ca/collections/collection_2010/sc-hc/H34-221-2010-eng.pdf Accessed 26 June 2017

New Zealand Ministry of Health. Our oral health: Key findings of the 2009 New Zealand oral health survey (NZOHS). Ministry of Health. 2010. http://www.health.govt.nz/publication/our-oral-health-key-findings-2009-new-zealand-oral-health-survey. Accessed 26 June 2017.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. National Center for Health Statistics. National Health and nutrition examination survey. 2005. https://wwwn.cdc.gov/nchs/nhanes/Default.aspx. Accessed 26 June 2017.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. National Center for Health Statistics. National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. https://wwwn.cdc.gov/nchs/data/nhanes3/ResponseRates/RRT0304MF.pdf. Accessed 16 February 2018.

National Institute of Dental Research. Oral Health of United States adult. National finding. NIH Publication. 87–2868. US Department of Health and Human Services, Public Service, National Institutes of Health, 1987.

StataCorp. Stata Statistical Software. Release 13. College Station: StataCorp LP; 2013.

Jylhä M. What is self-rated health and why does it predict mortality? Towards a unified conceptual model. Soc Sci Med. 2009;69:307–16.

O’Mullane DM, Baez RJ, Jones S, Lennon MA, Petersen PE, RuggGunn AJ, et al. Fluoride and oral health. Comm Dent Health. 2016;33:69–99.

Burt BA. Fluoridation and social equity. J Public Health Dent. 2002;62:195–200.

Do LG, Spencer AJ. Oral health-related quality of life of children by dental caries and fluorosis experience. J Public Health Dent. 2007;67(3):132–9.

Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion (ODPHP). Healthy People 2020. Washington: US Dept of health and human services; 2007. https://www.healthypeople.gov/2020/prevention-portal-508/office/office-of-disease-prevention-and-health-promotion. Accessed 26 June 2017

Hardy MA, Acciai F, Reyes AM. How health conditions translate into self-ratings: a comparative study of older adults across Europe. J Health Soc Behav. 2014;55:320–41.

Al-Zarea BK. Satisfaction with appearance and the desired treatment to improve aesthetics. Int J Dent. 2013;912368:7. https://doi.org/10.1155/2013/912368. Epub 2013 Feb 20.

Maghaireh GA, Alzaraikat H, Taha NA. Satisfaction with dental appearance and attitude toward improving dental esthetics among patients attending a dental teaching center. J Contemp Dent Pract. 2016;17:16–21.

Larsson P, John MT, Nilner K, List T. Normative values for the oro-facial esthetic scale in Sweden. J Oral Rehab. 2014;41:148–54.

Silva FBD, Chisini LA, Demarco FF, Horta BL, Correa MB. Desire for tooth bleaching and treatment performed in Brazilian adults: findings from a birth cohort. Braz Oral Res. 2018;32:e12.

Matthias RE, Atchison KA, Lubben JE, De Jong F, Schweitzer SO. Factors affecting self-ratings of oral health. J Public Health Dent. 1995;55:197–204.

Pattussi MP, Olinto MTA, Hardy R, Sheiham A. Clinical, social and psychosocial factors associated with self-rated oral health in Brazilian adolescents. Comm Dent Oral Epidemiol. 2007;35:377–86.

Pattussi MP, Peres KG, Boing AF, Peres MA, da Costa JSD. Self-rated oral health and associated factors in Brazilian elders. Comm Dent Oral Epidemiol. 2010;38:348–59.

Carlsson V, Hakeberg M, Blomkvist K, Boman UW. Orofacial esthetics and dental anxiety: associations with oral and psychological health. Acta Odontol Scand. 2014;78:703–13.

Allison P, Locker D, Jokovic A, Slade G. A cross-cultural study of oral health values. J Dent Res. 1999;78:643–9.

Dowd JB. Whiners, deniers, and self-rated health: what are the implications for measuring health inequalities? A commentary on Layes, et al. Soc Sci Med 2012;75:10–13.

Layes A, Adada Y, Kephart G. Whiners and deniers – what does self-rated health measure? Soc Sci Med. 2012;75:1–9.

Rousseau N, Steele J, May C, Exley C. Your whole life is lived through your teeth: biographical disruption and experiences of tooth loss and replacement. Sociol Health Illn. 2014;36:462–76.

Slade GD, Nuttall N, Sanders AE, Steele JG, Allen PF, Lahti S. Impacts of oral disorders in the United Kingdom and Australia. British Dent J. 2005;198:489–93.

Shaw M, Galobardes B, Lawlor D, Lynch J, Wheeler B, Davey-Smith G. The handbook of inequality and socioeconomic position: concepts and measures. Chicago: The Policy Press; 2007.

Funding

JSK was supported by the Canada Research Chairs program. SH was partially supported by a Chercheur-boursier Junior 2 grant from the Fonds de recherche du Québec—Santé. NSAOH was supported by Australian Government health agencies, including National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC) grants #299060, #349514, and #349537. The Australian Dental Association and state and territory health departments and dental services are also acknowledged. Colgate Oral Care provided gifts for participants.

Availability of data and materials

The data that support the Australian, New Zealand and Canadian findings are subject to third party restrictions; data are available from the authors upon reasonable request and with permission from pertinent data custodians. NSAOH data, used with permission for this study, are available from the Australian Research Centre for Population Oral Health, University of Adelaide. Similarly, access to New Zealand data used in this study is provided by Statistics New Zealand under conditions designed to keep individual information secure in accordance with requirements of the Statistics Act 1975. The opinions presented are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent an official view of Statistics New Zealand. Access to CHMS data was obtained through Statistics Canada’s Research Data Centres (RDC). NHANES data is publicly available on the CDC-National Center for Health Statistics website [https://wwwn.cdc.gov/nchs/nhanes/Default.aspx].

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

GM contributed to the conception and design of the study, data acquisition, analysis and interpretation, drafting of the manuscript, critical revisions and approval of the final version. HE contributed to conception and design, acquisition, analysis and interpretation of data, critical review of manuscript drafts and approval of version to be published. SH and JK contributed to the conception and design of the study, interpretation of data, critical review of manuscript and approval of final version. MT contributed to the conception and study design, acquisition of data, analysis and interpretation, critically reviewed the manuscript and approved the final version. XJ contributed to the analysis and interpretation of the data, was involved in drafting and reviewing the manuscript and approved the final version. IK critically revised the manuscript for important intellectual content and provided final approval. LJ contributed to the conception and design of the study, acquisition of the data, interpretation of results, critical review of manuscript drafts and provided final approval. All authors read and approved the final manuscript

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study is informed by a secondary analysis of national survey data; the authors obtained de-identified data from data custodians and had no contact with survey participants. Ethical approval for the original studies/surveys was obtained from the New Zealand Health and Disability Multi-region Ethics Committee (Approval number MEC/07/11/149), the University of Adelaide, NCHS Research Ethics Review Board (Protocol number 98–12) and Health Canada Research Ethics Board. Approval for the study presented in this paper was obtained from the institutional review board (IRB) of McGill University Faculty of Medicine (IRB study number A03-E25-13B; IRB Assurance Number FWA 00004545) and Harvard School of Public Health (protocol number IRB13–1201), which includes all countries included in the analysis.

Consent for publication

Not Applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Mejia, G.C., Elani, H.W., Harper, S. et al. Socioeconomic status, oral health and dental disease in Australia, Canada, New Zealand and the United States. BMC Oral Health 18, 176 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12903-018-0630-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12903-018-0630-3