Abstract

Background

Peri-implantitis (PI) is an inflammatory reaction associated with functional deterioration of supporting bones around the dental implant. Recent studies suggested Epstein–Barr virus (EBV) is involved in the pathogenesis of periodontitis. We investigated the association between EBV and Porphyromonas gingivalis in Japanese PI patients.

Methods

Fifteen periodontally healthy individuals, 15 healthy implant patients and 15 PI patients were recruited. Forty five subgingival plaque samples were collected from the deepest probing pocket depth (PPD) site from each patient. Real-time PCR was used to detect EBV DNA and P. gingivalis.

Results

EBV and P. gingivalis were detected in 7 and 3 PPD sites of the healthy controls, in 9 and 4 PPD sites of the healthy implants, and in 13 and 14 PPD sites of the PI patients. P. gingivalis and coexistence of EBV and P. gingivalis were detected significantly higher in the PI patients than healthy controls and healthy implant patients. EBV was detected significantly higher in the PI patients than healthy controls.

Conclusions

Higher levels of EBV and P. gingivalis were detected in PPD sites of PI patients. These results suggest that coexistence of EBV and P. gingivalis may serve pathogenic factors cause for PI in Japanese dental patients.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

The Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) is an enveloped herpes virus with double-stranded DNA [1]. EBV is one of the most common viruses, infecting more than 90% of the adult population worldwide [2, 3]. EBV infection is usually asymptomatic during childhood, but the infection leads to infectious mononucleosis when it is delayed until adolescence. It is transmitted from host to host by salivary contact, and the virus passes through the oropharyngeal epithelium to B lymphocytes, where it establishes a lifelong latent infection [4,5,6]. EBV is associated with Burkitt’s lymphoma, Hodgkin’s lymphoma, natural killer/T-cell lymphoma, post transplantation lymphoproliferative disorder and nasopharyngeal cancer [7,8,9]. EBV is adsorbed to CD21 receptors which are expressed on B lymphocyte [10,11,12]. The reactivation of EBV from latent infection occurs frequently and multiplies with the epithelium cells of the pharyngeal and is exhausted in saliva [13].

Association between EBV infection and periodontitis has been reported [14, 15]. Therefore, we have studied the relationship between EBV and Porphyromonas gingivalis which is representative periodontal disease pathogen in chronic periodontitis (CP). EBV DNA and P. gingivalis were detected in deeper periodontal pockets of Japanese CP patients [16, 17]. Our findings suggest that EBV DNA may serve as a pathogenic factor leading to CP. We also provide evidence for potential interactions between EBV and P. gingivalis in the etiopathogenesis of CP [17]. A systematic review indicated that herpesviruses including EBV are significantly associated with CP [18]. Lu et al. [19] reported an EBV and P. gingivalis coinfection may promote the development of CP among pregnant women.

Peri-implantitis (PI) is an inflammatory reaction associated with functional deterioration of supporting bones around dental implants [20]. PI is the most frequent long-term complications of dental implants [20,21,22,23,24]. It provokes bone destruction with suppuration (SUP), and encountered swelling and bleeding on probing (BOP) around implants. Clinical manifestations characterized by the destruction of bone are similar to periodontitis. Several studies showed that the periodontopathic bacteria are detected in PI sites and that these bacteria are also detected in periodontitis [25,26,27,28]. On the other hand, several studies suggest that the bacteria flora from PI sites were different from periodontitis sites, or tend to create ecologically different bacterial communities between PI and periodontitis [29,30,31,32].

Therefore, the purpose of this study was to examine whether EBV DNA and P. gingivalis are associated with deep pockets in Japanese PI patients.

Methods

Subjects and subject distribution

Fifteen periodontally healthy individuals (healthy controls: mean age, 55.5 ± 14.8 years), 15 healthy implant patients (mean age, 60.7 ± 10.0 years) and 15 PI patients (mean age, 63.9 ± 12.7 years) were included in this study. They received periodontal initial treatment at Nihon University Hospital School of Dentistry at Matsudo, Japan. The Institutional Review Board at the Nihon University School of Dentistry at Matsudo approved the study (EC14–11–027-1, EC15–005). Written informed consent was obtained from each study subject after all experiments were fully explained. Diagnosis of PI was defined as changes in the level of the crestal bone on radiographic examination in conjunction with BOP, with or without concomitant deepening of peri-implant pockets [33]. SUP is a common finding in PI sites. Healthy implant sites showed no clinical signs of peri-implant mucositis or PI. A group of 15 individuals without periodontitis were included as the healthy control group. The healthy controls showed no clinical signs of gingivitis or attachment loss, no detectable bone loss on radiographic examination, and a probing pocket depth (PPD) of ≤3 mm. All samples were taken from the deepest PPD site per patient (15 healthy controls, 15 healthy implant patients, and 15 PI patients). All patients were systemically healthy and had no history of periodontal treatment or any type of antibiotic therapy for at least three months prior to the present study.

Sampling

Fifteen subgingival plaque samples were collected from one periodontally healthy site of PPD (≤3 mm) among 15 healthy controls, and 15 subgingival plaque samples were collected from one healthy implant site of PPD (≤4 mm) among 15 healthy implant patients, and 15 subgingival plaque samples were collected from one PI site of PPD (≥5 mm) among 15 PI patients. Before sampling, supragingival plaque was removed with Gracey curette. Sterile paper points were inserted to the sample site (three times), retained for 30 s, pooled in Eppendorf tubes, and then stored at −80 °C [17].

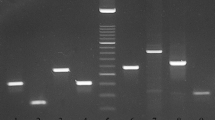

DNA extraction and real-time PCR

DNA samples from the subgingival plaque were prepared using High Pure Viral Nucleic Acid Kit (Roche Applied Science, Mannheim, Germany). Quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction (PCR) was used to measure the copy numbers of EBV DNA and P. gingivalis in the samples, using the following primer sets: EBV forward, 5′-CCTGGTCATCCTTTGCCA-3′; EBV reverse, 5′-TGCTTCGTTATAGCCGTAGT-3′; P. gingivalis forward, 5′-AGGCAGCTTGCCATACTGCG-3′; P. gingivalis reverse, 5′-ACTGTTAGCAACTACCGATGT-3′; glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) forward, 5′-GCACCGTCAAGGCTGAGAAC-3′; and GAPDH reverse, 5′-ATGGTGGTGAAGACGCCAGT-3′ [17]. SYBR Premix Ex Taq in a TP800 thermal cycler dice real-time system (Takara-bio, Tokyo, Japan) was used for real-time PCR reaction in a total volume of 25 μl (12.5 μl 2× SYBR Premix Ex Taq, 0.2 μl forward and reverse primers, and 12.1 μl as the DNA sample (300 ng per 1 well) and the PCR products comprised of 95 bp for EBV, 404 bp for P. gingivalis, and 142 bp for GAPDH. The thermal cycling conditions were 10 s at 95 °C, 45 cycles of 5 s at 95 °C and 30 s at 60 °C. The dynamic ranges of the real-time PCR assays were determined through serial dilution of DNA extracts either as AKATA cells or P. gingivalis TDC60 of the standards in the range of 109 ∼ 101copies/ml [34, 35].

Statistical analysis

The chi squared test for independence, confirmed by Fisher’s exact probability test, was used to determine whether individual pathogens were associated with PI, and to calculate the odds ratio. P values of <0.05 were considered to be statistically significant.

Results

The age, sex, PPD, BOP, SUP, loading time of implants and patient distribution are summarized in Table 1. The mean PPD of the healthy controls was 2.73 ± 0.44 mm (mean ± SD). The average PPD of the healthy implant sites and the PI sites were 2.87 ± 0.62 mm and 6.20 ± 1.60 mm, respectively. BOP was detected in 1 healthy implant site and 11 PI sites and undetectable in healthy controls. Moreover, SUP was detected in 9 PI sites. Table 2 shows clinical data and counts of EBV DNA and P. gingivalis (copies/ml) in the healthy controls. EBV DNA and P. gingivalis were detected in 7 of 15 healthy PPD sites (46.7%, range from 9.19 × 103~3.88 × 108 copies/ml) and 3 of 15 healthy PPD sites (20.0%, range from 9.17 × 106~1.31 × 109 copies/ml). Table 3 describes clinical data and counts of EBV DNA and P. gingivalis in the healthy implants. EBV DNA and P. gingivalis were detected in 9 of 15 healthy implant sites (60.0%, range from 1.71 × 104~2.97 × 108 copies/ml), and 4 of 15 healthy implant sites (26.7%, 2.38 × 107~6.79 × 1010 copies/ml). Table 4 shows clinical data and counts of EBV DNA and P. gingivalis in the PI sites. EBV DNA and P. gingivalis were detected in 13 of 15 PI sites (86.7%, range from 1.06 × 104~4.79 × 109 copies/ml), and 14 of 15 PI sites (93.3%, range from 5.4 × 106 ~ 4.42 × 1010 copies/ml). Loading time of healthy implant group and PI group were 4.45 ± 2.53 years (mean ± SD) and 5.63 ± 2.72 years, respectively (Table 1). Mean loading time of PI group was longer than healthy implant group. However, there was no significant difference between two groups.

The prevalence of EBV DNA and P. gingivalis in the healthy controls, healthy implants and PI sites are listed in Table 5. EBV DNA was detected significantly higher in the PPD sites of PI patients (86.7%) than healthy controls (46.7%), but not statistically significant higher than healthy implant patients (60.0%). P. gingivalis occurred at significantly higher frequencies in the PPD sites of PI patients (93.3%) than in the PPD sites of healthy controls (20.0%) and healthy implants (26.7%). Coexistence of EBV DNA and P. gingivalis was significantly higher in the PPD sites of PI patients (80.0%) than in the PPD sites of healthy controls (6.7%) and healthy implants (13.3%). To calculate the odds ratio of quantitative risk factors for PI, the findings of healthy implants and PI were compared with that of the healthy controls (Table 6). In the PPD sites of healthy implants, the odds ratios for EBV, P. gingivalis and the presence of both EBV and P. gingivalis were 1.71, 1.45 and 2.15. In the PPD sites of PI patients, higher odds ratios for EBV, P. gingivalis and both EBV and P. gingivalis were shown as 7.43, 56 and 56, respectively.

Discussion

In this study, we demonstrated for the first time that higher levels of EBV DNA, P. gingivalis and coexistence of EBV DNA and P. gingivalis were detected in deep PPD sites of Japanese PI patients compared with healthy controls and healthy implant patients. The results suggest that EBV and P. gingivalis may serve exacerbating factors caused by PI.

Although periodontopathic bacteria from pocket a reservoirs around periodontally compromised teeth are considered to be associated with for the subgingival plaque around implants in partially edentulous patients [26, 28, 36], it has become increasingly obvious that EBV is involved in the etiology of PI [37,38,39]. Bacterial activity alone is not sufficient to explain the following clinical characteristics of periodontitis, such as rapid bone resorption with minimal plaque, site specificity, and presence of active and quiescence phase [40, 41]. In this study, we examined whether higher prevalence of EBV DNA and P. gingivalis are associated with deeper PPD sites in Japanese PI patients, because several studies suggest that EBV and P. gingivalis act synergistically to potentiate periodontal disease progression and tissue destruction [16, 17, 19, 42, 43]. As expected, we detected higher levels of EBV DNA, P. gingivalis and coexistence of EBV DNA and P. gingivalis in deeper PPD sites of PI. EBV and human cytomegalovirus (HCMV) trigger a release of inflammatory cytokines that have the potential to activate osteoclasts and matrix metalloproteinases activities, impair antibacterial immune mechanisms, and permit the overgrowth of periodontopathic bacteria [41, 44, 45]. EBV may cooperate with P. gingivalis in the destruction of periodontal tissues [42, 45]. A significant correlation was found between presence of subgingival EBV and HCMV and clinical parameters of PI and healthy implant sites, and confirms the high prevalence of EBV and HCMV in subgingival plaque of PI sites [37]. PI lesions were 14.2 times and 3 times more likely to harbor EBV than healthy implant sites and saliva, respectively [39]. Verdugo et al. [46] reported saliva may act as a vehicle to transport EBV and periodontal pathogens into the sinus, and cause bone loss after sinus augmentation. Periodontal pathogen and EBV-associated periapical periodontitis might be the source of retrograde infectious PI [47]. Therefore, EBV could be a potential candidate in PI etiopathogenesis.

Gingival epithelial cells of the periodontium are commonly infected with EBV and may serve as an oral reservoir of latent EBV-infected cells, and the base level of epithelial EBV infection is significantly increased in periodontitis patients [48]. We have previously reported that the results of in situ hybridization of EBV-encoded small RNA (EBER) showed a large number of EBV-infected cells were observed in the inflamed gingival connective tissue subjacent to the gingival epithelium [16]. These results also support the high detection frequency of EBV DNA (46.7% and 60%) even in the gingival sulcus of healthy controls and healthy implant patients in the present study (Table 5).

The latent form of EBV can be induced to enter the lytic replication cycle by treatment with various inducers, such as phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate, anti-immunoglobulin, calcium ionophore, transforming growth factor-β and butyric acid [5, 6, 49]. The EBV BZLF1 gene product ZEBRA is a master regulator of the transition from latency to the lytic replication cycle. Hypoacetylation of histone in the BZLF1 promoter by histone deacetylase (HDAC) is involved in maintaining EBV latency. Culture supernatant of P. gingivalis is containing a high concentration of butyric acid which is an inhibitor of HDAC, increased histone acetylation and transcriptional activity of the BZLF1 gene [5, 6]. These findings suggest that periodontitis and PI are risk factors for EBV reactivation in infected individuals.

Our research provides evidence for potential interactions between EBV and P. gingivalis in the etiopathogenesis of peri-implantitis. EBV and periodontal pathogen co-existence apparently leads to synergistic effects and exacerbates the progress of periodontitis and peri-implant diseases [39, 45]. EBV-infected periodontitis and PI lesions tend to harbor elevated levels of periodontopathic bacteria. Viral and bacterial co-existences were reported more frequently in deeper PPD sites of CP patients [42, 50]. We have previously reported that coexistence of EBV DNA and P. gingivalis was significantly higher in patients with deeper PPD sites (40%) than in those with shallow PPD sites (14%) or healthy controls (13%) [16]. In addition, coexistence of EBV DNA and P. gingivalis was significantly higher in the deeper PPD sites of CP patients (68%) than in the PPD sites of the healthy controls (15%) and shallow PPD sites of CP patients (12%) [17]. These results support the opinion that a combined presence of EBV and P. gingivalis increases the risk of developing periodontitis and PI.

Further studies are necessary to establish the EBV as an etiological agent of PI. Prevention and new treatment could be developed as a strategy to keep latency of the EBV.

Conclusions

The results from our study showed that coexistence of EBV and P. gingivalis was detected significantly higher in the PI patients than healthy controls and healthy implant patients. These results suggest that coexistence of EBV and P. gingivalis may serve pathogenic factors cause for PI in Japanese dental patients.

Abbreviations

- BOP:

-

Bleeding on probing

- CP:

-

Chronic periodontitis

- EBV:

-

Epstein-Barr virus

- GAPDH:

-

Glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase

- HDAC:

-

Histone deacetylase

- PCR:

-

Polymerase chain reaction

- PI:

-

Peri-implantitis

- PM:

-

Peri-implant mucositis

- PPD:

-

Probing pocket depth

- SUP:

-

Suppuration

References

Tao Q, Young LS, Woodman CB, Murray PG. Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) and its associated human cancers--genetics, epigenetics, pathobiology and novel therapeutics. Front Biosci. 2006;11:2672–13.

Lin JC, Lin SC, De BK, Chan WP, Evatt BL. Precision of genotyping of Epstein-Barr virus by polymerase chain reaction using three gene loci (EBNA-2, EBNA-3C, and EBER): predominance of type a virus associated with Hodgkin's disease. Blood. 1993;81:3372–81.

Maeda E, Akahane M, Kiryu S, et al. Spectrum of Epstein-Barr virus-related diseases: a pictorial review. Jpn J Radiol. 2009;27:4–19.

Thorley-Lawson DA, Gross A. Persistence of the Epstein-Barr virus and the origins of associated lymphomas. N Engl J Med. 2004;350:1328–37.

Imai K, Inoue H, Tamura M, et al. The periodontal pathogen Porphyromonas gingivalis induces the Epstein-Barr virus lytic switch transactivator ZEBRA by histone modification. Biochimie. 2012;94:839–46.

Imai K, Kamio N, Cueno ME, et al. Role of the histone H3 lysine 9 methyltransferase Suv39 h1 in maintaining Epsteinn-Barr virus latency in B95-8 cells. FEBS J. 2014;281:2148–58.

Timms JM, Bell A, Flavell JR, et al. Target cells of Epstein-Barr-virus (EBV)-positive post-transplant lymphoproliferative disease: similarities to EBV-positive Hodgkin's lymphoma. Lancet. 2003;361:217–23.

Toussirot E, Roudier J. Epstein-Barr virus in autoimmune diseases. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol. 2008;22:883–96.

Lai KY, Chou YC, Lin JH, et al. Maintenance of Epstein-Barr virus latent status by a novel mechanism, latent membrane protein 1-induced interleukin-32, via the protein kinase Cδ pathway. J Virol. 2015;89:5968–80.

D'Addario M, Libermann TA, Xu J, Ahmad A, Menezes J. Epstein-Barr virus and its glycoprotein-350 upregulate IL-6 in human B-lymphocytes via CD21, involving activation of NF-kappaB and different signaling pathways. J Mol Biol. 2001;308:501–14.

Slots J, Saygun I, Sabeti M, Kubar A. Epstein-Barr virus in oral diseases. J Periodontal Res. 2006;41:235–44.

Corstjens PL, Abrams WR, Malamud D. Saliva and viral infections. Periodontol. 2016;70:93–110.

Ikuta K, Satoh Y, Hoshikawa Y, Sairenji T. Detection of Epstein-Barr virus in salivas and throat washings in healthy adults and children. Microbes Infect. 2000;2:115–20.

Kamma JJ, Contreras A, Slots J. Herpes viruses and periodontopathic bacteria in early-onset periodontitis. J Clin Periodontol. 2001;28:879–85.

Slots J, Kamma JJ, Sugar C. The herpesvirus-Porphyromonas gingivalis -periodontitis axis. J Periodontal Res. 2003;38:318–23.

Kato A, Imai K, Ochiai K, Ogata Y. Higher prevalence of Epstein-Barr virus DNA in deeper periodontal pockets of chronic periodontitis in Japanese patients. PLoS One. 2013;8(8):e71990.

Kato A, Imai K, Ochiai K, Ogata Y. Prevalence and quantitative analysis of Epstein-Barr virus DNA and Porphyromonas gingivalis associated with Japanese periodontitis patients. Clin Oral Investig. 2015;19:1605–10.

Zhu C, Li F, Wong MC, Feng XP, Lu HX, Xu W. Association between Herpesviruses and Chronic Periodontitis: A Meta-Analysis Based on Case-Control Studies. PLoS One 2015;10:e0144319.

Lu H, Zhu C, Li F, Xu W, Tao D, Feng X. Putative periodontopathic bacteria and herpesviruses in pregnant women: a case-control study. Sci Rep. 2016;6:27796.

Ogata Y, Nakayama Y, Tatsumi J, et al. Prevalence and risk factors for peri-implant diseases in Japanese adult dental patients. J Oral Sci. 2017;59:1–11.

Berglundh T, Gislason O, Lekholm U, Sennerby L, Lindhe J. Histopathological observations of human periimplantitis lesions. J Clin Periodontol. 2004;31:341–7.

Bullon P, Fioroni M, Goteri G, Rubini C, Battino M. Immunohistochemical analysis of soft tissues in implants with healthy and peri-implantitis condition, and aggressive periodontitis. Clin Oral Implants Res. 2004;15:553–9.

Carcuac O, Berglundh T. Composition of human peri-implantitis and periodontitis lesions. J Dent Res. 2014;93:1083–8.

Cornelini R, Artese L, Rubini C, et al. Vascular endothelial growth factor and microvessel density around healthy and failing dental implants. Int J Oral Maxillofac Implants. 2001;16:389–93.

Mombelli A, Decaillet F. The characteristics of biofilms in peri-implant disease. J Clin Periodontol. 2011;38(Suppl 11):203–13.

Papaioannou W, Quirynen M, Van Steenberghe D. The influence of periodontitis on the subgingival flora around implants in partially edentulous patients. Clin Oral Implants Res. 1996;7:405–9.

Renvert S, Lindahl C, Renvert H, Persson GR. Clinical and microbiological analysis of subjects treated with Brånemark or AstraTech implants: a 7-year follow-up study. Clin Oral Implants Res. 2008;19:342–7.

Shibli JA, Melo L, Ferrari DS, Figueiredo LC, Faveri M, Feres M. Composition of supra- and subgingival biofilm of subjects with healthy and diseased implants. Clin Oral Implants Res. 2008;19:975–82.

Koyanagi T, Sakamoto M, Takeuchi Y, Maruyama N, Ohkuma M, Izumi Y. Comprehensive microbiological findings in peri-implantitis and periodontitis. J Clin Periodontol. 2013;40:218–26.

Kumar PS, Mason MR, Brooker MR, O'Brien K. Pyrosequencing reveals unique microbial signatures associated with healthy and failing dental implants. J Clin Periodontol. 2012;39:425–33.

Dabdoub SM, Tsigarida AA, Kumar PS. Patient-specific analysis of periodontal and peri-implant microbiomes. J Dent Res. 2013;92(12 Suppl):168S–75S.

Maruyama N, Maruyama F, Takeuchi Y, Aikawa C, Izumi Y, Nakagawa I. Intraindividual variation in core microbiota in peri-implantitis and periodontitis. Sci Rep. 2014;4:6602.

Lang NP, Berglundh T. Periimplant diseases: where are we now? - consensus of the seventh European workshop on periodontology. J Clin Periodontol. 2011;38(Suppl 11):178–81.

Takada K, Horinouchi K, Ono Y, et al. An Epstein-Barr virus-producer line Akata: establishment of the cell line and analysis of viral DNA. Virus Genes. 1991;5:147–56.

Watanabe T, Maruyama F, Nozawa T, et al. Complete genome sequence of the bacterium Porphyromonas gingivalis TDC60, which causes periodontal disease. J Bacteriol. 2011;193:4259–60.

Mombelli A, Van Oosten MA, Schürch E, Lang NP. The microbiota associated with successful or failing osseointegrated titanium implants. Oral Microbiol Immunol. 1987;2:145–51.

Jankovic S, Aleksic Z, Dimitrijevic B, Lekovic V, Camargo P, Kenney B. Prevalence of human cytomegalovirus and Epstein-Barr virus in subgingival plaque at peri-implantitis, mucositis and healthy sites. A pilot study. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2011;40:271–6.

Jankovic S, Aleksic Z, Dimitrijevic B, Lekovic V, Milinkovic I, Kenney B. Correlation between different genotypes of human cytomegalovirus and Epstein-Barr virus and peri-implant tissue status. Aust Dent J. 2011;56:382–8.

Verdugo F, Castillo A, Castillo F, Uribarri A. Epstein-Barr virus associated peri-implantitis: a split-mouth study. Clin Oral Investig. 2015;19:535–43.

Socransky SS, Haffajee AD, Goodson JM, Lindhe J. New concepts of destructive periodontal disease. J Clin Periodontol. 1984;11:21–32.

Slots J. Human viruses in periodontitis. Periodontol. 2010;53:89–110.

Chalabi M, Rezaie F, Moghim S, Mogharehabed A, Rezaei M, Mehraban B. Periodontopathic bacteria and herpesviruses in chronic periodontitis. Mol Oral Micobiol. 2010;25:236–40.

Özcan E, Saygun NI, Serdar MA, Kubar A, Bengi VU. Porphyromonas gingivalis and Epstein-Barr Virus are associated with increased levels of visfatin in gingival crevicular fluid. J Periodontol. 2016;87:443–51.

Mogensen TH, Paludan SR. Molecular pathways in virus-induced cytokine production. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 2001;65:131–50.

Slots J. Herpesviral-bacterial interactions in periodontal diseases. Periodontol. 2010;52:117–40.

Verdugo F, Castillo A, Simonian K, et al. Periodontopathogen and Epstein-Barr virus contamination affects transplanted bone volume in sinus augmentation. J Periodontol. 2012;83:162–73.

Verdugo F, Castillo A, Simonian K, Castillo F, Farez-Vidal E, D'Addona A. Periodontopathogen and Epstein-Barr virus-associated periapical periodontitis may be the source of retrograde infectious peri-implantitis. Clin Implant Dent Relate Res. 2015;17:199–207.

Vincent-Bugnas S, Vitale S, Mouline CC, Khaali W, et al. EBV infection is common in gingival epithelial cells of the periodontium and worsens during chronic periodontitis. PLoS One. 2013;8(12):e80336.

Davies AH, Grand RJ, Evans FJ, Rickinson AB. Induction of Epstein-Barr virus lytic cycle by tumor-promoting and non-tumor-promoting phorbol esters requires active protein kinase C. J Virol. 1991;65:6838–44.

Saygun I, Kubar A, Sahin S, Sener K, Slots J. Quantitative analysis of association between herpesviruses and bacterial pathogens in periodontitis. J Periodontal Res. 2008;43:352–9.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

The study was supported by Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research (C; No. 17 K11994, C; No.16 K11526, Young (B); No.17 K17361) from the Ministry of Education, Science, Sports and Culture of Japan, and Nihon University Multidisciplinary Research Grant for 2017.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

AK, KI and YO were responsible for design and conception of the study. AK, HS and YO performed follow-up care of patients and sample collection. All authors were involved in the analysis and interpretation of data. AK and YO was responsible for drafting the manuscript. All authors revised it critically and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The study had been approved by the Institutional Review Board at the Nihon University School of Dentistry at Matsudo (EC14–11–027-1, EC15–005), in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. Verbal and written informed consent was received from each subject were then clinically examined.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Kato, A., Imai, K., Sato, H. et al. Prevalence of Epstein-Barr virus DNA and Porphyromonas gingivalis in Japanese peri-implantitis patients. BMC Oral Health 17, 148 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12903-017-0438-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12903-017-0438-6