Abstract

Background

Grasses are hyper-accumulators of silicon (Si) and often up-regulate Si following herbivory. Positive correlations exist between Si and plant water content, yet the extent to which Si uptake responses can be mediated by changes in soil water availability has rarely been studied and never, to our knowledge, under field conditions. We used field-based rain-exclusion shelters to investigate how simulated grazing (shoot clipping) and altered rainfall patterns (drought and elevated precipitation, representing 50% and 150% of ambient precipitation levels, respectively) affected initial patterns of root- and shoot-Si uptake in a native Australian grass (Microlaena stipoides) in Si-supplemented and untreated soils.

Results

Si supplementation increased soil water retention under ambient and elevated precipitation but not under drought, although this had little effect on Si uptake and growth (tiller numbers or root biomass) of M. stipoides. Changes in rainfall patterns and clipping had strong individual effects on plant growth and Si uptake and storage, whereby clipping increased Si uptake by M. stipoides under all rainfall treatments but to the greatest extent under elevated precipitation. Moreover, above-ground–below-ground Si distribution only changed following elevated precipitation by decreasing the ratio of root:shoot Si concentrations.

Conclusions

Results highlight the importance of soil water availability for Si uptake and suggest a role for both active and passive Si transport mechanisms. Such manipulative field studies may provide a more realistic insight into how grasses initially respond to herbivory in terms of Si-based defence under different environmental conditions.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

In defending themselves against herbivores, plants can tolerate (e.g. via compensatory regrowth) and/or resist (e.g. via production of toxic chemicals or defensive structures) herbivory. Investment in defence requires resources that could otherwise be invested in growth or reproduction, and are thus costly to the plant. In order to mitigate these costs, many plant defences are induced in response to damage instead of being constitutively expressed [1, 2]. Many species of grasses, for example, are frequently defoliated by grazing ungulates, and often tolerate herbivory by replacing lost biomass. In comparison to woody plants, grasses make limited use of secondary metabolites and structural components to resist herbivores, however [3]. Phytoliths (i.e. microscopic deposits of silica, SiO2), in particular, confer defence against herbivores through abrasion on their mouthparts and diminished nutrient acquisition via reduced palatability and digestibility of foliage [4]. While grasses generally show fewer defences based on secondary metabolites than other plant taxa, Si may prime production of chemical defences, especially those associated with the jasmonic acid pathway (e.g. [5]).

Many grasses are hyper-accumulators of silicon (Si), sometimes accumulating up to 10% of their dry mass, more than any other inorganic constituent [6]. Their capacity for Si accumulation varies among species, however, with some species taking up more Si from the soil than predicted from the rate of transpiration (these are termed “active accumulators”) and others the same or even less (“passive” and “rejective” accumulators, respectively) [7, 8]. Si, as an energetically cheaper resource for plant structural support, may trade-off with carbon (C)-based defences [9]. Thus, plants that have high Si uptake typically have lower levels of C, and only recently has this been demonstrated in the roots [10]. Indeed, most studies have considered Si accumulation in the shoots, with little experimental work on how biotic and abiotic factors affect Si uptake and accumulation in the roots. This may provide only a partial insight because the majority of Si is often stored in the roots [11] and if Si is retained in the roots this would likely affect the extent to which Si accumulates in the shoots.

While changes in the Si-accumulating responses of grasses have been linked to grazing [2, 12], and have been associated with an active Si transport mechanism, others have identified no (e.g. [13]) or species-specific (e.g. [14]) Si uptake responses to grazing. Emerging evidence suggests that Si uptake can vary with soil Si availability, root and shoot biomass, and transpiration rate [15, 16], yet there is particular controversy over the extent to which induction responses can be mediated by changes in soil water availability and transpiration rate [17]. Moreover, as highlighted by SE Hartley and JL DeGabriel [4], we lack field-based data about how grasses accumulate Si, especially under different environmental conditions.

Plants can only acquire Si via uptake of silicic acid (Si(OH)4) from soil water by the roots [18]. Thus, decreases in soil water availability might be predicted to impair Si uptake. Increases in extreme precipitation events, including drought and elevated precipitation predicted for the future [19, 20], have a number of impacts on plant growth, physiology, nutrition and allocation to defences [21,22,23], yet we know relatively little about how water stress affects Si uptake and deposition, especially in non-crop plants. Some studies have shown that Si levels in grasses decline under drought [13, 24], whereas others suggest that grasses can maintain uptake [25, 26].

Using a field-based rain-exclusion experimental facility, this study aimed to determine how the growth and chemical characteristics of weeping grass (Microlaena stipoides Labill.) respond to water stress (drought and elevated precipitation), simulated grazing (i.e. clipping) and the application of Si to the soil, with a particular focus on changes in silicification of above- and below-ground tissues. Microlaena stipoides is common within grazed native pastures in the high rainfall zone (> 550 mm average annual rainfall) of south-eastern Australia [27] and is highly valued for its fodder quality, year round growth and resistance to drought. It is adapted to a wide variety of soil types and has been shown to accumulate high levels of shoot Si [28], making it an excellent candidate for testing Si uptake responses to water availability and grazing. Based on the high Si-accumulating capacity of grasses, their tendency to up-regulate Si in response to herbivory [12] and the importance of water availability in determining Si accumulation [13], we hypothesised that simulated grazing would increase Si uptake in M. stipoides roots and shoots, which would be enhanced by increased levels of precipitation. Moreover, Si might substitute for C as a cheaper plant structural resource [9], so increases in Si uptake were expected to coincide with decreases in C concentrations.

Methods

Rain-exclusion shelters

Rain-exclusion shelters (249 cm × 188 cm) located at the Hawkesbury campus of Western Sydney University near Richmond, NSW (latitude − 33.609396, longitude 150.737800), as described by Johnson et al. [29], were used to exclude 100% of ambient rainfall from four mesocosms beneath each of 18 shelters. Mesocosm pots (41 cm × 41 cm × 31 cm) were arranged in a 2 × 2 formation and dug into the ground so that the rim of the pot was flush with the soil surface. Each of the 72 mesocosms was filled with the excavated soil (chemical composition defined in Additional file 1: Table S1; methods from GE Rayment and DJ Lyons [30]), which was air-dried and sieved to < 4 mm.

Experimental procedure

Six Microlaena stipoides (var. Burra) seeds were sown and grown in 288 individual seed cells (38 × 57 mm) under field conditions. After 4 weeks (on 26 September 2016), four cells were transplanted into each mesocosm pot. Shelters were assigned at random to one of three rainfall treatments giving six shelters per rainfall regime. The ambient treatment was set at 65 mm per month, which was the average precipitation in Richmond between September and November over the previous 30 years (Bureau of Meteorology, Australia). The drought and elevated precipitation treatments comprised 50% and 150% of the ambient rainfall amounts, respectively. This translated to an application of 586 mL (ambient precipitation), 293 mL (drought) and 878 mL (elevated precipitation) of rainfall water collected at the site three times per week. Soil moisture measurements were taken weekly using a 12 cm Hydrosense II probe (Campbell Scientific, Queensland, Australia).

Each of two of the four mesocosms underneath each shelter were supplemented with Si by dissolving 146.5 mg of sodium metasilicate (Na2SiO3.9H2O) into the water applied under each watering regime. Four weeks after transplantation, grasses in two of the four mesocosms (one with Si applied and one without) were clipped, using hand shears, to leave approximately 40% of their aboveground biomass. The factorial treatment design under each shelter therefore comprised one mesocosm with Si applied alone (Si), one mesocosm with clipped grasses alone (Clipped), one mesocosm with both treatments applied (Si + Clipped), and one mesocosm with neither (Control; Fig. 1a). Plant heights and tiller numbers were recorded every 2 weeks throughout the experiment and whole plants were harvested 7 weeks after transplanting (when plants were 11 weeks old). Soil samples were taken from the centre of each mesocosm at a depth of approximately 5 cm and oven-dried. Roots were separated from shoots and frozen at − 20 °C, then oven-dried and weighed prior to chemical analysis.

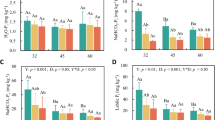

Schematic diagram of experimental plots beneath one rain-exclusion shelter (a). Significant treatment effects of rainfall, silicon application (Si) and simulated grazing (Clipping) on soil water content (b), the number of tillers (c) and root mass (d). Significance indicated by *(P < 0.05), **(P < 0.01), ***(P < 0.001). Values are means (± SE). Bars with the same letters were not significantly different (P < 0.05) according to Tukey's post hoc tests. Timeline of experimental events shown (c)

Chemical analyses

Dried root and shoot material and soil samples were ball-milled to a fine powder. Plant material from each mesocosm was pooled to provide enough dried material to conduct chemical analyses, giving one root and shoot sample per mesocosm (i.e. 72 roots and 72 shoots). Carbon (C) and nitrogen (N) concentrations were determined with a Carlo Erba CE1110 elemental analyser and total Si concentrations (% of dry soil mass) were determined with an X-ray fluorescence spectrometer (Epsilon-3x, PANalytical, EA Almelo, The Netherlands), as described in I Hiltpold, L Demarta, SN Johnson, BD Moore, SA Power and C Mitchell [31]. The “uptake efficiency” of Si (mg Si per mg root mass) was calculated by dividing the total content of Si in foliar tissue (i.e. % Si × shoot mass) by the total root mass.

Statistical analyses

The R statistical interface v3.3.3 [32] was used to conduct statistical analyses. Impacts of simulated grazing, Si-application and rainfall on plant and soil chemistry (C, N and Si concentrations) were analysed using general linear models (based on pooled plant samples for each mesocosm). Plant growth characteristics (height until clipped, root mass and tiller numbers) and soil moisture were analysed with mixed models in the nlme statistical package [33], with mesocosm number and time (date) as random effects to account for repeated measures. The fixed terms for all models included clipping (clipped and unclipped), Si-application (Si + and Si −) and rainfall (ambient precipitation, drought and elevated precipitation). Two-way and three-way interactions between these terms were included in the model. Pairwise comparisons of means for treatment and interaction effects were made with Tukey’s post hoc tests utilising the glht function in the multcomp package [34]. Where necessary, dependent variables were transformed before analysis (Table 1). Correlations between Si and C concentrations were determined using the function cor.test in the package stats.

Results

Soil moisture and plant growth

Soil moisture was significantly affected by the interaction between rainfall and Si-application (Table 1), whereby soil moisture retention increased when Si was applied to the soil, but only under ambient and elevated precipitation conditions (Fig. 1b). Before the clipping treatment was applied, heights were significantly lower under drought compared with ambient and elevated precipitation and increased in Si-supplemented soils compared with untreated soils (Table 1). In general, plants under drought had significantly fewer tillers than those under ambient and elevated precipitation. Similarly, plants that were clipped had fewer tillers than those that were not clipped (Fig. 1c). Tiller numbers did not differ significantly between plants grown in Si-supplemented (13.18 ± 0.33) and untreated (12.62 ± 0.35) soil. Root mass decreased in plants subjected to drought, whereas root mass in plants under elevated precipitation did not vary significantly from those under ambient precipitation (Fig. 1d). Root mass was not significantly affected by clipping (clipped: 59.04 ± 2.50, unclipped: 70.18 ± 4.06) or Si-application (supplemented: 59.57 ± 2.97, untreated 64.65 ± 4.06). Full statistical results are shown in Table 1.

Soil and plant chemistry

At the experiment’s conclusion, the Si concentration of Si-supplemented soil was significantly higher than soil that was not supplemented with Si (Fig. 2a), which likely reflected an increase in bioavailable silicon in the soil (c. 21 mg kg−1). The application of Si had no significant effect on the concentration of Si in the roots or shoots of M. stipoides, however. When plants were clipped, the concentrations of Si in the roots and shoots increased by 12 and 41%, respectively, compared with those that were not clipped (Fig. 2b). Grass roots and shoots tended to have higher concentrations of Si (Fig. 2b) and lower concentrations of C (Fig. 2c) under elevated precipitation compared with drought and ambient rainfall conditions, although these effects were less pronounced in the roots (Table 1). Root chemistry, in particular, responded more to drought than elevated precipitation, with Si and C concentrations decreasing and increasing, respectively, under drought compared with ambient rainfall. Concentrations of C and Si were negatively correlated (Fig. 2d). Moreover, Si concentrations in the roots relative to the shoots (i.e. the ratio of root to shoot Si) were significantly reduced in plants under elevated precipitation compared with those under ambient precipitation and drought. In other words, high water availability increased the uptake of Si in plant shoots relative to concentrations in their roots (Table 1). Rainfall had a significant effect on Si uptake efficiency (F2,30 = 39.83, P < 0.001), which increased by 84% under elevated precipitation (11.87 ± 0.75) and decreased by 40% under drought (3.89 ± 0.35) relative to ambient rainfall conditions (6.46 ± 0.76). In general, average soil moisture content was positively correlated with root (r = 0.25, P = 0.034, df = 70) and shoot Si concentrations (r = 0.61, P < 0.001, df = 70) and negatively correlated with root (r = − 0.26, P = 0.025, df = 70) and shoot C concentrations (r = 0.55, P < 0.001, df = 70). Root N concentrations increased and decreased under elevated precipitation (1.68 ± 0.03%) and drought (1.32 ± 0.03%), respectively, relative to ambient rainfall (1.53 ± 0.04%), whereas shoot N concentrations did not vary between treatments. Rainfall, Si-application and clipping had no significant effects on soil C or N concentrations (Table 1).

The effects of rainfall, silicon application (Si) and simulated grazing (Clipping) on soil silicon concentrations (a), Microlaena stipoides root and shoot silicon (b) and carbon (c) concentrations and negative correlations (± 95% CI) between concentrations of silicon and carbon (d). Significance indicated by *(P < 0.05), **(P < 0.01), ***(P < 0.001). Values of bars are means (± SE). Bars with the same letters were not significantly different (P < 0.05) according to Tukey's post hoc tests

Discussion

Only a handful of empirical studies [13, 35] have attempted to quantify the relative importance of biotic factors (e.g. grazing) and abiotic factors (e.g. water availability) on plant silicification, particularly in the field, as was recently highlighted by SE Hartley and JL DeGabriel [4]. The current study is one of the first experiments to manipulate precipitation regimes in relation to simulated grazing and Si uptake.

Soil and plant responses to Si-application and water availability

The application of Si to the soil increased the retention of water in the soil, especially as rainfall increased, which was likely responsible for the increase in plant height in Si-supplemented plots observed before the clipping treatment was applied. The observed increase in soil water could be associated with either a physical effect of Si-application on the soil profile (via improved soil structure and water penetration; [36]) or an increase in plant water-use efficiency [37]. The application of Si in the form of Na2SiO3 could slightly increase soil concentrations of sodium (Na), though treatment concentrations were very low (1 mM) and field soil has the capacity to dissipate impacts. In any case, plants would most likely be unaffected as uptake of Na tends to decrease as plants take up Si [38].

Silicification of leaves has been shown to reduce water loss by as much as 30% in rice [39] and increase the biomass of drought-stressed wheat by 36% [40]. In this case, however, plant shoot and root Si concentrations did not respond to Si-application despite the increase in soil Si concentrations, suggesting that the uptake of plant-available H4SiO4 by M. stipoides may already be sufficient in the natural soil environment for optimal growth [41]. Under stressful conditions (e.g. grazing) or high water availability, however, the allocation of Si to structural defence or the passive uptake of Si, respectively, may increase, resulting in an increase in Si above the optimal level for plant growth [42].

Root and shoot Si concentrations and Si uptake efficiency were positively correlated with soil moisture, demonstrating the importance of plant water status in driving Si uptake and storage [13]. The accumulation of Si was associated with decreases in plant C concentrations, a trade-off response that has been identified in other grass species above- [43] and below-ground [10]. More specifically, however, the Si concentration of M. stipoides shoots relative to that of their roots was maintained under drought but was significantly higher under elevated precipitation, which was also evident in plants that had been clipped. The maintenance of shoot Si deposition under drought may be caused by or responsible for the drought tolerance that M. stipoides is generally known for [44], likely associated with osmotic adjustment and nutrient regulation [45]. Other grass species have been shown to maintain [25] or reduce foliar Si uptake under drought [24, 46]. Species-specific differences may be associated with changes in life-history strategies coupled with costs associated with Si accumulation [9]. Alternatively, the benefits of improved drought tolerance associated with Si accumulation in some species may outweigh the relative importance in others [47].

The effects of simulated grazing on plant growth and chemistry

Silicification patterns in roots are understudied, despite evidence that Si concentrations can occur at highest levels in these tissues [11]. This study quantified the short-term changes in Si dynamics in both above-ground and below-ground tissues. In terms of plant growth, the results demonstrated that simulated grazing decreased the number of tillers but had no effect on below-ground biomass. Therefore, no compensatory growth in response to clipping occurred. Instead, M. stipoides responded to clipping by storing Si in its roots and shoots, indicative of an induced defensive response, which was consistent across all watering regimes. Kindomihou et al. [14] also identified a Si-uptake response to simulated grazing in three of five tropical fodder grass species, whereas KM Quigley and TM Anderson [13] identified no effects of simulated grazing on Si accumulation in two Serengeti grasses, suggesting that Si uptake responses are contingent upon plant identity and/or grazing intensity. Grasses that respond to wounding by increasing Si uptake likely involve active processes that are regulated at the gene level, as demonstrated by E McLarnon, S McQueen-Mason, I Lenk and SE Hartley [16]. The effects of simulated grazing on C concentrations showed clear opposite responses to Si concentrations, which were correlated in both roots and shoots and were consistent across all rainfall treatments. Si clearly helps protect grasses from wounding but this investment in structural defence may limit C sequestration.

Simulated herbivory may not mimic natural damage exactly but it enables researchers to control the type, timing and intensity of damage with fewer confounding effects [48], which is especially useful in field systems such as this. Plants subjected to simulated grazing combined with the application of phagostimulants or natural herbivory by grazing vertebrates increase plant defensive responses more than those that are subjected to simulated grazing alone [4]. Moreover, studies with repeated defoliation events (i.e. continuous wounding) have been shown to increase the Si content of grasses compared with single defoliation events, with Si concentrations increasing by up to 400% in response to leaf damage [2] and persisting for several months ([16] and references therein). Microlaena stipoides may therefore show an even greater defence response in the form of higher grazing-induced uptake of Si when subjected to herbivore attack. High levels of rainfall may further enhance Si uptake by increasing transpiration overall [13], with implications for reducing palatability and digestibility by herbivores. Drought, however, is likely to reduce this defensive response to promote resource-conservation (i.e. water and nutrient-uptake) over investment in plant structural defence [49]. Above-ground–below-ground Si distribution only changed under elevated precipitation, under which shoot Si concentrations increased relative to root concentrations. Si may therefore remain in the roots until plants have enough water to enable the transfer of Si from the roots to the shoots.

Conclusions

This study provides clear evidence that water availability influences Si-based responses to damage in plants under field conditions. In particular, Si uptake responses to simulated grazing were enhanced when soil water availability was not limited, which are likely linked to a combination of active and passive uptake mechanisms. Field-based approaches such as this are fundamental to our understanding of how biotic and abiotic factors contribute to silicification in plants [4]. Studies that further incorporate changes in grazing intensity of above- and below-ground tissues would significantly advance our understanding of plant Si dynamics and its ecological importance.

Abbreviations

- C:

-

carbon

- N:

-

nitrogen

- Si:

-

silicon

- SiO2 :

-

silica

References

Kaplan I, Halitschke R, Kessler A, Sardanelli S, Denno RF. Constitutive and induced defenses to herbivory in above- and belowground plant tissues. Ecology. 2008;89(2):392–406.

Massey FP, Ennos AR, Hartley SE. Herbivore specific induction of silica-based plant defences. Oecologia. 2007;152(4):677–83.

Vicari M, Bazely DR. Do grasses fight back? The case for antiherbivore defences. Trends Ecol Evol. 1993;8(4):137–41.

Hartley SE, DeGabriel JL. The ecology of herbivore-induced silicon defences in grasses. Funct Ecol. 2016;30(8):1311–22.

Ye M, Song Y, Long J, Wang R, Baerson SR, Pan Z, Zhu-Salzman K, Xie J, Cai K, Luo S, et al. Priming of jasmonate-mediated antiherbivore defense responses in rice by silicon. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2013;110(38):E3631–9.

Epstein E. Silicon. Annu Rev Plant Physiol Plant Mol Biol. 1999;50(1):641–64.

Hodson MJ, White PJ, Mead A, Broadley MR. Phylogenetic variation in the silicon composition of plants. Ann Bot. 2005;96(6):1027–46.

Takahashi E, Ma J, Miyake Y. The possibility of silicon as an essential element for higher plants. Comments Agric Food Chem. 1990;2(2):99–102.

Cooke J, Leishman MR. Tradeoffs between foliar silicon and carbon-based defences: evidence from vegetation communities of contrasting soil types. Oikos. 2012;121(12):2052–60.

Frew A, Powell JR, Sallam N, Allsopp PG, Johnson SN. Trade-offs between silicon and phenolic defenses may explain enhanced performance of root herbivores on phenolic-rich plants. J Chem Ecol. 2016;42(8):768–71.

Debona D, Rodrigues FA, Datnoff LE. Silicon’s role in abiotic and biotic plant stresses. Annu Rev Phytopathol. 2017;55:4.1–4.23.

McNaughton SJ, Tarrants JL. Grass leaf silicification: natural selection for an inducible defense against herbivores. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1983;80(3):790–1.

Quigley KM, Anderson TM. Leaf silica concentration in Serengeti grasses increases with watering but not clipping: insights from a common garden study and literature review. Front Plant Sci. 2014;5:568.

Kindomihou V, Sinsin B, Meerts P. Effect of defoliation on silica accumulation in five tropical fodder grass species in Benin. Belgian J Bot. 2006;139(1):87–102.

Ma JF, Yamaji N, Tamai K, Mitani N. Genotypic difference in silicon uptake and expression of silicon transporter genes in rice. Plant Physiol. 2007;145(3):919–24.

McLarnon E, McQueen-Mason S, Lenk I, Hartley SE. Evidence for active uptake and deposition of Si-based defenses in tall fescue. Front Plant Sci. 2017;8:1199.

Exley C. A possible mechanism of biological silicification in plants. Front Plant Sci. 2015;6:853.

Ma JF, Yamaji N. Silicon uptake and accumulation in higher plants. Trends Plant Sci. 2006;11(8):392–7.

Chiew FHS, Young WJ, Cai W, Teng J. Current drought and future hydroclimate projections in southeast Australia and implications for water resources management. Stoch Environ Res Risk Assess. 2011;25(4):601–12.

IPCC. Climate Change 2007: the physical science basis, contribution of working group I to the fourth assessment report of the intergovernmental panel on climate change: Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, United Kingdom and New York, NY, USA; 2007.

Mokany K, Ferrier S. Predicting impacts of climate change on biodiversity: a role for semi-mechanistic community-level modelling. Divers Distrib. 2011;17(2):374–80.

Knapp AK, Fay PA, Blair JM, Collins SL, Smith MD, Carlisle JD, Harper CW, Danner BT, Lett MS, McCarron JK. Rainfall variability, carbon cycling, and plant species diversity in a mesic grassland. Science. 2002;298(5601):2202–5.

Jamieson MA, Trowbridge AM, Raffa KF, Lindroth RL. Consequences of climate warming and altered precipitation patterns for plant-insect and multitrophic interactions. Plant Physiol. 2012;160(4):1719–27.

Eneji AE, Inanaga S, Muranaka S, Li J, Hattori T, An P, Tsuji W. Growth and nutrient use in four grasses under drought stress as mediated by silicon fertilizers. J Plant Nutr. 2008;31(2):355–65.

Kvedaras OL, Keeping MG, Goebel FR, Byrne MJ. Water stress augments silicon-mediated resistance of susceptible sugarcane cultivars to the stalk borer Eldana saccharina (Lepidoptera: Pyralidae). Bull Entomol Res. 2007;97(2):175–83.

Ryalls JMW, Moore BD, Johnson SN, Connor M, Hiltpold I. Root responses to domestication, precipitation and silicification: weeping meadow grass simplifies and alters toughness. Plant Soil. 2018;427(1–2):291–304.

Mitchell M, Stodart B, Virgona J. Genetic diversity within a population of Microlaena stipoides, as revealed by AFLP markers. Aust J Bot. 2014;62(7):580–6.

Johnson SN, Hartley SE. Elevated carbon dioxide and warming impact silicon and phenolic-based defences differently in native and exotic grasses. Glob Change Biol. 2018;24(9):3886–96.

Johnson SN, Lopaticki G, Barnett K, Facey SL, Powell JR, Hartley SE. An insect ecosystem engineer alleviates drought stress in plants without increasing plant susceptibility to an aboveground herbivore. Funct Ecol. 2016;30(6):894–902.

Rayment GE, Lyons DJ. Soil chemical methods: Australasia, vol. 3. Collingwood: CSIRO publishing; 2011.

Hiltpold I, Demarta L, Johnson SN, Moore BD, Power SA, Mitchell C. Silicon and other essential element composition in roots using X-ray fluorescence spectroscopy: a high throughput approach. In: Johnson SN, editor. Invertebrate Ecology of Australasian Grasslands: 2016. Hawkesbury: Western Sydney University; 2016. p. 191–6.

R Core Team. R: a language and environment for statistical computing. Vienna: R Foundation for Statistical Computing; 2017.

Pinheiro J, Bates D, DebRoy S, Sarkar D. nlme: linear and nonlinear mixed effects models. R package version 3.1–131. 2017. http://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/nlme/index.html.

Hothorn T, Bretz F, Westfall P. Simultaneous inference in general parametric models. Biom J. 2008;50(3):346–63.

Wieczorek M, Zub K, Szafrańska PA, Książek A, Konarzewski M. Plant–herbivore interactions: silicon concentration in tussock sedges and population dynamics of root voles. Funct Ecol. 2015;29(2):187–94.

Khattab H. Roles of silicon in improving drought tolerance in plants. In: Tripathi D, Singh V, Ahmad P, Chauhan D, Prasad S, editors. Silicon in plants: advances and future prospects. Boca Raton: CRC Press; 2016. p. 265–97.

Gao X, Zou C, Wang L, Zhang F. Silicon improves water use efficiency in maize plants. J Plant Nutr. 2005;27(8):1457–70.

Kafi M, Rahimi Z. Effect of salinity and silicon on root characteristics, growth, water status, proline content and ion accumulation of purslane (Portulaca oleracea L.). Soil Sci Plant Nutr. 2011;57(2):341–7.

Rogers WE, Siemann E. Invasive ecotypes tolerate herbivory more effectively than native ecotypes of the Chinese tallow tree Sapium sebiferum. J Appl Ecol. 2004;41(3):561–70.

Gong HJ, Chen KM, Chen GC, Wang SM, Zhang CL. Effects of silicon on growth of wheat under drought. J Plant Nutr. 2003;26(5):1055–63.

Deshmukh R, Bélanger RR. Molecular evolution of aquaporins and silicon influx in plants. Funct Ecol. 2016;30(8):1277–85.

Power SA, Barnett KL, Ochoa-Hueso R, Facey SL, Gibson-Forty EVJ, Hartley SE, Nielsen UN, Tissue DT, Johnson SN. DRI-Grass: a new experimental platform for addressing grassland ecosystem responses to future precipitation scenarios in South-East Australia. Front Plant Sci. 2016;7:1373.

Ryalls JMW, Hartley SE, Johnson SN. Impacts of silicon-based grass defences across trophic levels under both current and future atmospheric CO2 scenarios. Biol Lett. 2017;13(3):1–5.

Waters C, Huxtable C, Whalley W. Microlaena stipoides (Microlaena). In: Williams JT, editor. Grassed up: guidelines for revegetating with Australian native grasses. Dubbo: NSW Agriculture; 2000. p. 59–61.

Rizwan M, Ali S, Ibrahim M, Farid M, Adrees M, Bharwana SA, Zia-Ur-Rehman M, Qayyum MF, Abbas F. Mechanisms of silicon-mediated alleviation of drought and salt stress in plants: a review. Environ Sci Pollut Res. 2015;22(20):15416–31.

Epstein E. Silicon: its manifold roles in plants. Ann Appl Biol. 2009;155(2):155–60.

Cooke J, DeGabriel JL, Hartley SE. The functional ecology of plant silicon: geoscience to genes. Funct Ecol. 2016;30(8):1270–6.

Hjältén J. Simulating herbivory: problems and possibilities. In: Weisser WW, Siemann E, editors. Insects and ecosystem function, vol. 173., BerlinSpringer: Heidelberg; 2004. p. 243–55.

de Vries FT, Brown C, Stevens CJ. Grassland species root response to drought: consequences for soil carbon and nitrogen availability. Plant Soil. 2016;409(1):297–312.

Ryalls JMW, Moore BD, Johnson SN. Data from: Silicon uptake by a pasture grass experiencing simulated grazing is greatest under elevated precipitation. BMC Ecol. 2018. https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.7361378.v1.

Authors’ contributions

JMWR, SNJ and BDM conceived the experimental design. JMWR acquired, processed and analysed the data. All authors contributed to the interpretation and drafting of the manuscript and take responsibility for the integrity of the work as a whole. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful to Lisa Bromfield and Andrew Gherlenda for their assistance in the field.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Availability of data and materials

Data from this paper are available at the Figshare digital repository at https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.7361378.v1 [50].

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Funding

The study was funded by the Australian Research Council (Discovery projects ARC DP14100636 awarded to SNJ and BDM, DP170102278 and Future Fellowship FT170100342 awarded to SNJ).

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional file

Additional file 1: Table S1.

Chemical composition of excavated soil (N = 12) used in the experimental study.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Ryalls, J.M.W., Moore, B.D. & Johnson, S.N. Silicon uptake by a pasture grass experiencing simulated grazing is greatest under elevated precipitation. BMC Ecol 18, 53 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12898-018-0208-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12898-018-0208-6