Abstract

Background

BRCA1-Associated-Protein 1 (BAP1) is a dynamic tumor suppressor which, when mutated, has been associated with an increased risk of uveal melanoma, cutaneous melanoma, mesothelioma, and several other cancers. Germline BAP1 mutations have been extensively studied, where they have been found to cause hereditary cancer susceptibility. However, their sporadic counterparts, tumors that display a loss of BAP1 expression due to somatically arising mutations in the BAP1 gene, remain a poorly described entity.

Case presentation

Here we present the case of a 49-year-old female who presented with an asymptomatic dome-shaped pink papule on the dorsal foot which was found on biopsy to be deficient in the BAP1 tumor suppressor. While the patient’s family history did not suggest the presence of a familial cancer syndrome, germline genetic testing was performed and was negative. The patient underwent surgical excision of this sporadically appearing “BAPoma” by Mohs surgery.

Conclusions

Given the relatively banal clinical appearance of these dome-shaped neoplasms, sporadic BAPomas may often be overlooked by clinicians and dermatologists. In addition to providing a representative case, here we also provide a synopsis of the current understanding of these neoplasms, both in terms of the histopathological features, as well as the molecular mechanisms underlying BAP1 function and its ability to prevent tumorigenesis.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Within the last decade, the BRCA1-Associated-Protein 1 (BAP1) has been increasingly appreciated for its tumor suppressor activities, given that a loss of BAP1 can drive carcinogenesis in diverse tissue types. Germline mutations in BAP1 have been described in families with a hereditary increase in the risk of uveal melanoma, cutaneous melanoma, mesothelioma, Merkel cell carcinoma, and several other cancers [1]. Strikingly, a large-scale systematic review found that patients with BAP1 mutations face increased mortality, both general and cancer-specific, as well as increased likelihood of cancer relapse [2]. Thus, mutations in BAP1, along with family history, can be used as an assessment for a patient’s risk of certain cancers, and confers importance to the knowledge of a patient’s BAP1 mutation status.

More recently, sporadic somatic BAP1 mutations have been shown to occur in the setting of both mesothelioma and uveal melanoma [3]. In the skin, various neoplasms deficient in BAP1 have been described, typically presenting as dome-shaped to pedunculated growths which range from pink to light brown in color [1, 4]. These BAP1 negative tumors, or “BAPomas”, can be screened for using immunohistological staining, following which genetic testing can confirm the presence or absence of a BAP1 mutation in the germline. Sporadic BAPomas have been less thoroughly studied and reported than their familial counterparts. We present the case of a patient who presented with a sporadic BAPoma, describe her management, and provide a brief update on the current understanding of BAPoma histopathological categorization and BAP1 function.

Case presentation

A 49-year-old female presented with an asymptomatic pink to purple dome-shaped papule on the third digit of her right foot (Fig. 1). She has a history of actinic keratoses, but otherwise no other dermatological issues. Her family history is significant for a history of colon cancer and prostate cancer, as well as hypertension, hyperlipidemia, coronary artery disease, and diabetes, but no history of breast or ovarian cancer. A shave biopsy was performed.

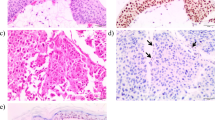

The sample proved to be a primarily dermal melanocytic proliferation (Fig. 2a), with a low proliferative index as determined by Ki67 staining. The lesion contained nests and strands of atypical epithelioid melanocytes surrounded by lymphocytes and pigmented macrophages (Fig. 2b). The lesion stained positive for MART-1 (Fig. 3a), however, BAP1 staining was negative (Fig. 3b), leading to the diagnosis of a BAPoma with epithelioid atypia and rare mitoses. Given that the atypical cells extended to the margins of the biopsy, a re-excision was recommended and the patient underwent Mohs surgery to clear the lesion. Although her personal and family history was not suggestive of a BAP1-associated cancer syndrome, the patient underwent genetic testing for a germline mutation in the BAP1 gene. Sequencing and deletion/duplication analysis of the BAP1 gene was negative, evidence supporting a sporadic BAP1 mutation in the lesion where the BAPoma formed. As there are no clear guidelines on screening for other cancers such as renal cell carcinoma or mesothelioma in these patients, only continued screening for cutaneous was recommended.

MART-1 staining (a) demonstrates positive staining of both typical (red arrows) and atypical melanocytes (yellow arrows). b BAP1 staining does not highlight the nuclei of atypical cells (yellow arrows), but does stain typical melanocytes (red arrows), suggesting the atypical epithelioid melanocytes have lost BAP1 expression

Discussion

Prior to the discovery of its key tumor suppressor role, BAP1 was primarily known for its role as a deubiquitinase. Ubiquitination is a common post translational modification by which proteins can be marked for degradation, with ubiquitin ligases and deubiquitinase working in opposition to maintain quality control of cellular proteins. In addition its clear role in ubiquitination and maintaining protein balance, BAP1 has been shown to be critical for a range of cellular processes associated with cancer, including differentiation and DNA repair [5, 6]. In addition, BAP1 has been implicated in the DNA damage response through its involvement in the ataxia telangiectasia-mutated (ATM) signaling pathway, as well as in epigenetic transcriptional regulation associated with preventing cancerous proliferation [7,8,9].

This basic knowledge has helped unravel BAP1’s role in tumor suppression in vivo. The 90 kDa protein was initially thought to reduce tumorigenesis through the deubiquitination of BRCA1, though it was later revealed that BAP1 can achieve its tumor suppressive role independently of BRCA1 [10]. Mechanistically, BAP1 localizes to the nucleus and employs its deubiquitinase activity to promote G1/S cell cycle transition and the induction of cell death, likely through impairment of normal DNA repair processes [10, 11]. Consistent with this, lung cancer cells with mutant BAP1 typically possess truncations or other mutations that negatively impact its deubiquitinase and nuclear localization ability. Most recently, extensive mechanistic work has demonstrated that BAP1-deficient cells not only accumulate increased levels of DNA damage, but also are unable to undergo apoptosis as compared to similarly damaged cells with normal levels of BAP1 [12]. In melanocytes, which undergo less turnover than neighboring keratinocytes, this accumulated damage likely combines with a failure of DNA repair and apoptosis to the increased chance of neoplastic proliferation seen both in patients with both inherited and sporadic deficiency of BAP1.

Histopathologically, cutaneous BAPomas are usually intradermal, comprised of a majority epithelioid melanocytes and containing large amounts of amphophilic cytosol with well-distinguished boundaries [4]. Some authors have classified these sporadic tumors into the heterogeneous of umbrella of atypical Spitz tumors, given that spitzoid melanocytic neoplasms can display immunohistochemical BAP1 staining that may be positive, negative, or only perinuclear with absent nuclear staining [13]. However, positive BRAFV600E expression in many BAP1 negative lesions, as well as a lack of epidermal hyperplasia, clefting between melanocytes, and Kamino bodies, sets this population apart from traditional Spitz nevi [4, 14]. Indeed, the study of both sporadic and germline BAPomas has and will continue to provide new insights into a previously unknown tumor suppressive pathway in the skin.

Abbreviations

- ATM:

-

Ataxia telangiectasia-mutated

- BAP1:

-

BRCA1-Associated-Protein 1

References

Wiesner T, Obenauf AC, Murali R, et al. Germline mutations in BAP1 predispose to melanocytic tumors. Nat Genet. 2011;43(10):1018–21.

Luchini C, Veronese N, Yachida S, et al. Different prognostic roles of tumor suppressor gene BAP1 in cancer: a systematic review with meta-analysis. Genes Chromosomes Cancer. 2016;55(10):741–9.

Rai K, Pilarski R, Cebulla CM, Abdel-Rahman MH. Comprehensive review of BAP1 tumor predisposition syndrome with report of two new cases. Clin Genet. 2016;89(3):285–94.

Wiesner T, Murali R, Fried I, et al. A distinct subset of atypical Spitz tumors is characterized by BRAF mutation and loss of BAP1 expression. Am J Surg Pathol. 2012;36(6):818–30.

Qiu GZ, Sun W, Jin MZ, Lin J, Lu PG, Jin WL. The bad seed gardener: Deubiquitinases in the cancer stem-cell signaling network and therapeutic resistance. Pharmacol Ther. 2016;

Huang X, Dixit VM. Drugging the undruggables: exploring the ubiquitin system for drug development. Cell Res. 2016;26(4):484–98.

Ismail IH, Davidson R, Gagne JP, Xu ZZ, Poirier GG, Hendzel MJ. Germline mutations in BAP1 impair its function in DNA double-strand break repair. Cancer Res 2014;74(16):4282-4294.

Dey A, Seshasayee D, Noubade R, et al. Loss of the tumor suppressor BAP1 causes myeloid transformation. Science. 2012;337(6101):1541–6.

LaFave LM, Beguelin W, Koche R, et al. Loss of BAP1 function leads to EZH2-dependent transformation. Nat Med. 2015;21(11):1344–9.

Ventii KH, Devi NS, Friedrich KL, et al. BRCA1-associated protein-1 is a tumor suppressor that requires deubiquitinating activity and nuclear localization. Cancer Res. 2008;68(17):6953–62.

Carbone M, Yang H, Pass HI, Krausz T, Testa JR, Gaudino G. BAP1 and cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 2013;13(3):153–9.

Bononi A, Giorgi C, Patergnani S, et al. BAP1 regulates IP3R3-mediated Ca2+ flux to mitochondria suppressing cell transformation. Nature. 2017;546(7659):549–53.

Gammon B, Traczyk TN, Gerami P. Clumped perinuclear BAP1 expression is a frequent finding in sporadic epithelioid Spitz tumors. J Cutan Pathol. 2013;40(6):538–42.

Yeh I, Mully TW, Wiesner T, et al. Ambiguous melanocytic tumors with loss of 3p21. Am J Surg Pathol. 2014;38(8):1088–95.

Acknowledgements

We appreciate Penn Cutaneous Pathology Services for their assistance in the pathological examination and interpretation of this case.

Funding

B.C.C. is supported by NIH K08 (AR07028901).

Availability of data and materials

All data from this manuscript are available within the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

KG and BCC wrote the manuscript. B.M. created the figures. KG, BM, WDJ, and BCC all edited and commented on the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This case was not a part of a clinical trial, but rather a patient seen during routine care in the dermatology clinic. The patient has consented to participate in this publication (see below and attached consent).

Consent for publication

The patient provided informed consent for the use and publication of the images in this manuscript. The consent has been uploaded with the manuscript files.

Competing interests

All authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Ghosh, K., Modi, B., James, W.D. et al. BAP1: case report and insight into a novel tumor suppressor. BMC Dermatol 17, 13 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12895-017-0065-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12895-017-0065-6