Abstract

Background

A history of prior cancer commonly results in exclusion from cancer clinical trials. However, whether a prior cancer history has an adversely impact on clinical outcomes for patients with advanced prostate cancer (APC) remains largely unknown. We therefore aimed to investigate the impact of prior cancer history on these patients.

Methods

We identified patients with advanced prostate cancer diagnosed from 2004 to 2010 in the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) database. Propensity score matching (PSM) was used to balance baseline characteristics. Kaplan–Meier method and the Cox proportional hazard model were utilized for survival analysis.

Results

A total of 19,772 eligible APC patients were included, of whom 887 (4.5 %) had a history of prior cancer. Urinary bladder (19 %), colon and cecum (16 %), melanoma of the skin (9 %) malignancies, and non-hodgkin lymphoma (9 %) were the most common types of prior cancer. Patients with a history of prior cancer had slightly inferior overall survival (OS) (AHR = 1.13; 95 % CI [1.02–1.26]; P = 0.017) as compared with that of patients without a prior cancer diagnosis. Subgroup analysis further indicated that a history of prior cancer didn’t adversely impact patients’ clinical outcomes, except in patients with a prior cancer diagnosed within 2 years, at advanced stage, or originating from specific sites, including bladder, colon and cecum, or lung and bronchus, or prior chronic lymphocytic leukemia.

Conclusions

A large proportion of APC patients with a prior cancer history had non-inferior survival to that of patients without a prior cancer diagnosis. These patients may be candidates for relevant cancer trials.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Prostate cancer represents the most common malignancy in men, accounting for estimated 164,690 new cases in the United States, in 2018 [1]. According to the latest statistical report, prostate cancer still represents the second most common cause of death in men (9 % of all cancer deaths) [2]. Although great advances have been made in the past several years, huge challenges still exist in patients with advanced prostate cancer, which is still associated with substantial morbidity and mortality, particularly in patients who develop resistance after multiple lines of therapy. The National Comprehensive Cancer Network hold the opinion that the best management for those patients with advanced disease is clinical trials, because well-designed clinical trials are pivotal for exploring new treatments and improving patients’ clinical outcomes. Unfortunately, patients who had a prior cancer history are often excluded by strict eligibility criteria in cancer trial. Given the dramatical increase in the number of cancer survivors as well as the decreasing cancer mortality rate, the exclusion criterion may limit the accrual and generalizability of clinical trials, and thus leaves many pivotal clinical issues unanswered [3, 4].

It was reported that up to 18 % of lung cancer patients were unconditionally excluded by over 80 % of lung cancer trials due to a history of prior cancer [5]. This practice is mainly due to concerns regarding to prior treatment interference and its survival impact, though little evidence clearly support this assumption. However, a previous retrospective study made by Laccetti et al. reported that a prior cancer history did not adversely affect survival of patients with advanced lung cancer, regardless of different stage or types of prior cancer [6]. Another study also suggested that the prognosis of patients with uterine papillary serous carcinoma was not affected by a prior breast cancer and tamoxifen exposure [7]. On the contrary, it was also reported that the overall survival were significantly lower in breast cancer patients as the second primary cancer than in that of patients with breast cancer as the primary cancer [8]. These different results implied that the survival impact of a prior cancer may vary among different cancer types. However, until recently, it remain unknown whether a history of prior cancer affects the clinical outcomes of APC patients.

Therefore, we conducted this study to assess the prevalence, types, timing, and prognostic impact of a prior cancer diagnosis on patients who developed advanced prostate cancer as a second primary malignancy by using the SEER database. Our finding may provide implications for exclusion criteria of relevant clinical trial.

Methods

Data source and case selection

The SEER*Stat software (v. 8.3.6.1) was utilized to extract data from the custom SEER database [Incidence- SEER 18 Regs Custom Data (with additional treatment fields), Nov 2018 Sub (1975–2016 varying)], which covers approximately 28 % of the United States population [9]. We included patients who were diagnosed with advanced prostate cancer (site code C) from 2004 to 2010 in order to ensure a 5-year follow-up at least. Patients were eligible if they had stage IV prostate cancer (N1M0 or M1) according to the 8th edition of the AJCC Cancer Staging Manual. Only patients with a single primary tumor or patient who had exactly one prior tumor were included. Other exclusion criteria were listed as follows: (1) patients whose prior cancer was prostate cancer; (2) patients with incomplete follow-up; (3) patients with only death certificates or autopsy records; (4) patients whose diagnosis time of malignancy was not known.

Covariates

Multiple variables including demographic characteristics (diagnosed year, age, race, and marital status), disease characteristics (Seer stage, histologic grade, and prior cancer type), and treatment modalities (surgery, chemotherapy and radiotherapy). Marital status was categorized as single, married and other status (divorced, widowed, separated and domestic partner). The record of SEER sequence number was used to determine the prior cancer diagnosis. For example, patients who had only one primary tumor were recorded as “00”. For patients with multiple malignancies, the sequence number of “01” represented the first tumor, and “02” represented the second one, and so forth. We then calculated the timing, namely the time interval between two cancer record, by subtracting the diagnosis date of the prior cancer from that of index prostate cancer. Detections of vital status and cause-specific death classification were used to define the primary outcomes including overall survival (OS) and cancer-specific survival (CSS).

Statistical analysis

Pearson chi-square test was utilized to compare clinicopathologic characteristics between patients with or without prior cancer. The propensity score matching (PSM) method was used to reduce the bias in baseline characteristics. Propensity scores were calculated based on variables including age, diagnosed year, race, marital status, histological grade, surgery, chemotherapy, and radiotherapy, with a ratio of 1:1 and a calliper of 0.2 [10]. Kaplan–Meier method and log-rank test were utilized to compare differences of OS in patients with no prior cancer vs. any prior cancer, before and after PSM. Multivariate Cox proportional hazards models were also built to determine whether prior cancer affects patients’ prognosis independently. Descriptive statistic, Pearson Chi-square test, and Cox proportional hazards model were performed using SPSS 24.0 (IBM Corp). The Kaplan–Meier plot and log-rank test were plotted or conducted by using R software version 4.0.0. A 2-sided P value of < 0.05 was considered as statistical significance unless otherwise stated.

Results

A total of 19,772 eligible APC patients were extracted from SEER database, of whom 887 (4.5 %) carried a history of prior cancer. As shown in Table 1, the median age at prior cancer diagnoses was 70 years old, and that of subsequent APC was 77 years old. The median (interquartile range, IQR) time interval between two cancer diagnoses was 49 (22-95.5) months (Table 1). The Table 2 indicated that a history of prior cancer was more common among the elderly (75.6 years vs. 69.3 year), black (84.7 % vs. 75.4 %), and married (65.8 % vs. 59.8 %) individuals. After propensity score matching (PSM), all the baseline characteristics between patients with or without prior cancer history were balanced (Table 2). Figure 1 showed that the most common types of prior cancer in APC survivors included urinary bladder (19 %), colon and cecum (16 %), melanoma of the skin (9 %), and non-hodgkin lymphoma (9 %).

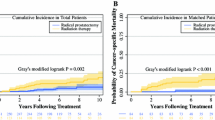

The Kaplan–Meier plot was utilized to compare the OS between patients who had, or had not prior cancer. As shown in Fig. 2a, the OS of patients with a history of prior cancer was dramatically lower (P < 0.001) than that of patients without a prior cancer history. After PSM, the Kaplan–Meier plot still showed a worse survival for patients who had a history of prior cancer, presenting a potential adverse effect of a prior cancer history on clinical outcome (P = 0.004) of patients with subsequent advanced prostate cancer (Fig. 2b).

In order to further investigate the survival impact of prior cancer, subgroup analyses were subsequently performed for APC patients stratified by timing (time interval), stage categorization and types of prior cancer. As shown in Fig. 3, we found that patients who had a prior cancer diagnosis with time interval of 2 years or longer showed non-inferior prognosis (P > 0.05) to that of patients without a prior cancer diagnosis. We also found that only prior cancer with advanced stage had significantly adverse impact on OS, while no survival detriment was observed in patients with a prior cancer diagnosed at in situ, localized, or regional stage (Fig. 4). Furthermore, our results also showed that a prior bladder, colon and cecum, lung and bronchus cancer, or CLL had a dramatically (P < 0.05) adverse effect on survival of patients with subsequent advanced prostate cancer (Fig. 5 and Additional file 1: Fig. S1). However, patients whose prior cancers originating from other sites presented similar OS as compared with that of patients without a prior cancer diagnosis.

Kaplan–Meier survival curves of prior cancer impact on the overall survival (OS) stratified by timing of prior cancer in patients with advanced prostate cancer. a The OS analysis with time interval less than 1 year; b The OS analysis with time interval between 1–2 year; c The OS analysis with time interval between 2–3 year; d The OS analysis with time interval between 3–5 year; e The OS analysis with time interval between 5–10 year; f The OS analysis with time interval longer than 10 years

Kaplan–Meier survival curves of prior cancer impact on the overall survival (OS) stratified by stage of prior cancer in patients with advanced prostate cancer. a The OS analysis with prior cancer at in situ stage; b The OS analysis with prior cancer at localized stage; c The OS analysis with prior cancer at regional stage; (D) The OS analysis with prior cancer diagnosed at advanced stage

Kaplan–Meier survival curves of prior cancer impact on the overall survival (OS) stratified by different types of prior cancer in patients with advanced prostate cancer. a The impact of prior bladder cancer on OS; b The impact of prior colon and cecum cancer on OS; c The impact of prior melanoma skin cancer on OS; d The impact of prior non-hodgkin lymphoma on OS; e The impact of prior rectum cancer on OS; f The impact of prior lung and bronchus cancer on OS

After adjusted for age, race, marital status, histologic grade, and treatment modalities, the multivariate Cox regression analysis showed that a prior cancer history was significantly associated with worse OS (HR = 1.13; 95 % CI [1.02–1.26]) for patients with advanced prostate cancer (Table 3). Similar to the Kaplan–Meier method, the multivariate Cox analysis for the subgroup analysis further demonstrated that only prior cancer with time interval less than 1 years (HR = 1.35; 95 % CI [1.11–1.66]) or within 1–2 years (HR = 1.27; 95 % CI [1.02–1.57]), with prior cancer diagnosed at advanced stage (HR = 1.31; 95 % CI [1.08–1.58]), or with prior cancer of bladder (HR = 1.39; 95 % CI [1.16–1.66]), colon and cecum (HR = 1.23; 95 % CI [1.02–1.48]), lung and bronchus cancer (HR = 1.54; 95 % CI [1.15–2.08]) or CLL (HR = 1.47; 95 % CI [1.01–2.15]) significantly affected the prognosis of patients with advanced prostate cancer. Nevertheless, patients with other different timing, with other stage categorization or with other types of prior cancer had non-inferior survival to that of patients without a prior cancer diagnosis. Our result also showed that patients with a history of prior cancer presented non-inferior or even slightly superior prostate cancer-specific survival to patients without a prior cancer history. Detailed data can be seen in Table 3.

Discussion

This study focused on survival impact of a prior cancer history on APC patients. Approximately 4.5 % of patients with advanced prostate cancer had a prior cancer history. Those patients showed a worse prognosis in comparison with patients without a prior cancer diagnosis. Nevertheless, subgroup analyses indicated that a history of prior cancer didn’t adversely affect patients’ survival, except for patients with prior cancer diagnosed within 2 year, or those with prior cancer diagnosed at advanced stage, or those with specific types of prior cancer, including bladder, colon and cecum, lung and bronchus cancer, or CLL .

Over the last few decades, the population of cancer survivors has been steadily increasing in the United States because of the aging of the population and the great advances in early detection and cancer treatment [11,12,13]. This population had a high risk of developing second primary cancer [14, 15]. Previous study reported that about one-tenth of younger adults and one-fourth of the elderly cancer patients had a prior cancer history [16].

Similar to other types of cancer, prostate cancer is frequently diagnosed as a second malignancy. In our study, we focused on assessing the survival impact of a prior cancer history on APC patients who are often candidates for clinical trials. We found that approximately 4.5 % of patients had exactly one non-prostate prior cancer before the diagnosis of APC. This proportion was similar to advanced breast cancer but lower than advanced lung cancer [6, 17]. Besides, similar to studies reported by Bluethmann et al. [16] and Murphy et al. [18], our study suggested that the elderly patients were more likely to have a history of prior cancer than the younger patients. The median time interval between advanced prostate cancer and prior cancers was approximately four years, which was longer than some cancers [3, 8]. The urinary bladder, colon and cecum, melanoma of the skin, and Non-hodgkin lymphoma exhibited as the most common types of prior cancer in the APC patients, of which the distribution differs from other cancers, such as nasopharyngeal cancer [3], lung cancer [19] and breast cancer [8].

The cancer trials exerts as a promising way for improving survivorship of advanced cancer patients. However, fewer than 5 % of patients can be enrolled in cancer trials due to the overly restrictive exclusion criteria [20], and a history of prior cancer was the commonly used one in most trials. This could mainly due to the widely accepted belief that a prior cancer can adversely affect patients’ survival, though no authoritative data have proved it. The stringent criteria may weed out a large number of patients who had urgent need, which could limit generalizability and lead to premature trial termination [4, 21]. Therefore, liberalizing the exclusion criteria, especially for a history of prior cancer, has been proposed by several working groups [5, 22]. Furthermore, the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has introduced a draft guidance implying that patients who had a prior cancer history could generally be enrolled in clinical trials [23].

Our data indicated that the overall survival of APC patients with a history of prior cancer was significantly poorer than that of patients without a prior cancer history before and after PSM method. This result was consistent to the pan-cancer study by Zhou et al. [24]. However, subsequent subgroup analyses revealed that a prior cancer history could impair the survival of patients only when the interval time was less than two year. This time-frame finding was different from the study by Lin et al. that demonstrated no survival detriment in patients with advanced breast cancer who had prior cancer outside the timeframe of 4 years [17].

Our study also demonstrated that a prior cancer diagnosed at in situ, localized, or regional stage didn’t adversely affect the OS of APC patients. Moreover, subgroup analysis further showed that an inferior OS was only observed in APC survivors who had prior cancer originating from bladder, colon and cecum, or lung and bronchus, or prior CLL. In addition, these aforementioned results were further confirmed by the multivariable Cox analysis after adjusting for various clinicopathological variables. Hence, our data implied that a large number of APC patients who had a history of prior cancer may be eligible candidates for relevant cancer trials.

There are also several limitations in our study. First, other information such as efficacy and toxicity of treatment on prior cancer could not be considered due to lack of relevant data. Second, selection bias is inherent because of the intrinsic weaknesses of retrospective study. Therefore, further study is warranted to confirm the generality of our findings.

Conclusion

In conclusion, a large number of APC patients have a prior cancer history. Only prior cancer diagnosed within two year, at advanced stage, or some specific prior cancer adversely affect APC patients’ survival. Therefore, for APC cancer patients with prior cancer history, broader inclusion criterion should be adopted to increase the accrual rate for the relevant clinical cancer trials.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets generated and/or analysed during the current study are available in the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results Program repository, https://seer.cancer.gov/data/.

Abbreviations

- APC:

-

Advanced prostate cancer

- SEER:

-

Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results

- OS:

-

Overall survival

- CSS:

-

Cancer-specific survival

- PSM:

-

Propensity score matching

- HR:

-

Adjusted hazard ratio

- IQR:

-

Interquartile range

- CLL:

-

Chronic lymphocytic leukemia

References

Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2018. Cancer J Clin. 2018;68(1):7–30.

Saad F, Shore N, Zhang T, Sharma S, Cho HK, Jacobs IA. Emerging therapeutic targets for patients with advanced prostate cancer. Cancer Treat Rev. 2019;76:1–9.

Wang YQ, Lv JW, Tang LL, Du XJ, Chen L, Li WF, Liu X, Guo Y, Lin AH, Mao YP, et al. Effect of prior cancer on trial eligibility and treatment outcomes in nasopharyngeal carcinoma: Implications for clinical trial accrual. Oral Oncol. 2019;90:23–9.

Filion M, Forget G, Brochu O, Provencher L, Desbiens C, Doyle C, Poirier B, DuRocher M, Camden S, Lemieux J. Eligibility criteria in randomized phase II and III adjuvant and neoadjuvant breast cancer trials: not a significant barrier to enrollment. Clin Trials. 2012;9(5):652–9.

Gerber DE, Laccetti AL, Xuan L, Halm EA, Pruitt SL. Impact of prior cancer on eligibility for lung cancer clinical trials. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2014;106(11):302.

Laccetti AL, Pruitt SL, Xuan L, Halm EA, Gerber DE. Effect of prior cancer on outcomes in advanced lung cancer: implications for clinical trial eligibility and accrual. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2015;107(4):dvj002.

Pierce SR, Stine JE, Gehrig PA, Havrilesky LJ, Secord AA, Nakayama J, Snavely AC, Moore DT, Kim KH. Prior breast cancer and tamoxifen exposure does not influence outcomes in women with uterine papillary serous carcinoma. Gynecol Oncol. 2017;144(3):531–5.

Ji F, Yang CQ, Li XL, Zhang LL, Yang M, Li JQ, Gao HF, Zhu T, Cheng MY, Li WP, et al. Risk of breast cancer-related death in women with a prior cancer. Aging. 2020;12(7):5894–906.

Cronin KA, Ries LA, Edwards BK. The Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) Program of the National Cancer Institute. Cancer. 2014;120(Suppl 23):3755–7.

Austin PC. An introduction to propensity score methods for reducing the effects of confounding in observational studies. Multivar Behav Res. 2011;46(3):399–424.

de Moor JS, Mariotto AB, Parry C, Alfano CM, Padgett L, Kent EE, Forsythe L, Scoppa S, Hachey M, Rowland JH. Cancer survivors in the United States: prevalence across the survivorship trajectory and implications for care. Cancer Epidemiol Biomark Prev. 2013;22(4):561–70.

Miller KD, Siegel RL, Lin CC, Mariotto AB, Kramer JL, Rowland JH, Stein KD, Alteri R, Jemal A. Cancer treatment and survivorship statistics, 2016. Cancer J Clin. 2016;66(4):271–89.

Oh CM, Won YJ, Jung KW, Kong HJ, Cho H, Lee JK, Lee DH, Lee KH. Cancer Statistics in Korea: incidence, mortality, survival, and prevalence in 2013. Cancer Res Treat. 2016;48(2):436–50.

Travis LB, Demark Wahnefried W, Allan JM, Wood ME, Ng AK. Aetiology, genetics and prevention of secondary neoplasms in adult cancer survivors. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2013;10(5):289–301.

Wood ME, Vogel V, Ng A, Foxhall L, Goodwin P, Travis LB. Second malignant neoplasms: assessment and strategies for risk reduction. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30(30):3734–45.

Murphy CC, Gerber DE, Pruitt SL. Prevalence of prior cancer among persons newly diagnosed with cancer: an initial report from the surveillance, epidemiology, and end results program. JAMA Oncol. 2018;4(6):832–6.

Lin C, Wu J, Ding S, Goh C, Andriani L, Shen K, Zhu L. Impact of prior cancer history on the clinical outcomes in advanced breast cancer: a propensity score-adjusted, population-based study. Cancer Res Treat. 2020;52(2):552–62.

Bluethmann SM, Mariotto AB, Rowland JH. Anticipating the “Silver Tsunami”: prevalence trajectories and comorbidity burden among older cancer survivors in the United States. Cancer Epidemiol Biomark Prev. 2016;25(7):1029–36.

Laccetti LA, Pruitt LS, Lei, Xuan AE, Halm ED, Gerber. Effect of prior cancer on outcomes in advanced lung cancer: implications for clinical trial eligibility and accrual.J Natl Cancer Inst 2015.

Kim ES, Bruinooge SS, Roberts S, Ison G, Lin NU, Gore L, Uldrick TS, Lichtman SM, Roach N, Beaver JA, et al. Broadening eligibility criteria to make clinical trials more representative: American Society of Clinical Oncology and Friends of Cancer Research Joint Research Statement. J Clin Oncol. 2017;35(33):3737–44.

Lemieux J, Goodwin PJ, Pritchard KI, Gelmon KA, Bordeleau LJ, Duchesne T, Camden S, Speers CH. Identification of cancer care and protocol characteristics associated with recruitment in breast cancer clinical trials. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26(27):4458–65.

Gerber DE, Pruitt SL, Halm EA. Should criteria for inclusion in cancer clinical trials be expanded? J Comp Effect Res. 2015;4(4):289–91.

Administration TFaD. Cancer Clinical Trial Eligibility Criteria: Patients with Organ Dysfunction or Prior or Concurrent Malignancies. Washington, DC: The Food and Drug Administration c2019 [cited 2019 Mar 7]. https://www.fda.gov/Drugs/GuidanceComplianceRegulatoryInformation/Guidances/default.htm.

Zhou H, Huang Y, Qiu Z, Zhao H, Fang W, Yang Y, Zhao Y, Hou X, Ma Y, Hong S, et al. Impact of prior cancer history on the overall survival of patients newly diagnosed with cancer: a pan-cancer analysis of the SEER database. Int J Cancer. 2018;143(7):1569–77.

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledged the efforts of the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) Program tumor registries in the creation of the SEER database.

Funding

This work was financially supported by the Grants 19-E-41 from Shanghai Baoshan District Medical and Health Project.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

YW, TC contributed to study conception and design. YW, XC, DQ contributed to data acquisition. YW, WW, YZ contributed to analysis and interpretation data. JH, JZ, QW contributed to drafting the manuscript. QW, TC were involved in revising the manuscript. All authors have read and approved the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

All analyses of human data conducted in this study were approved by the Institutional Review Board of The Shuguang Hospital Affiliated to Shanghai University of Traditional Chinese Medicine and in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. Informed consent was exempted because of the retrospective nature of this study. All authors signed authorization forms and received permission from SEER to access and use the dataset.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1:

Fig. S1. Kaplan-Meier survival curves of prior cancer impact on the overall survival (OS) stratified by different types of prior cancer in patients with advanced prostate cancer. (A) The impact of prior kidney cancer on OS; (B) The impact of prior chronic lymphocytic leukemia on OS; (C) The impact of prior larynx cancer on OS; (D) The impact of prior others cancer on OS.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Wu, Y., Chen, X., Qian, D. et al. Effect of prior cancer on survival outcomes for patients with advanced prostate cancer. BMC Urol 21, 26 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12894-021-00792-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12894-021-00792-w