Abstract

Background

For recurrent incarcerated and strangulated hernias, the optimal treatment strategy for each case is needed.

Case presentation

The study patient was a 70-year-old man. TAPP repair was performed for a left inguinal hernia (JHS Classification II-1) 7 years earlier. The patient experienced transient pain and swelling of the left inguinal region for 5 months and visited our emergency department for abdominal pain and vomiting. A CT scan showed a recurrent left inguinal hernia and small bowel incarceration, and emergency surgery was performed. Laparoscopic observation of the abdominal cavity revealed recurrent left inguinal hernia (Rec II-1) with small bowel incarceration. The small bowel was reduced after pneumoperitoneum, and no findings suggested intestinal tract necrosis. Adhesions around the herniated sac were dissected using an extraperitoneal approach and then shifted to mesh plug repair. No perioperative complications or hernia recurrence were observed in the 10 months after the surgery.

Conclusions

This report describes a novel, successful surgical treatment for a recurrent incarcerated hernia. In our patient, we could easily perform dissection and understand the positional relationship by hybrid surgery using the TEP method. Additionally, in patients with incarcerated hernias, we believe that performing hybrid surgery by combining the TEP method would be useful because bowel dilation caused by intestinal obstruction would not disturb the operative field.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Recurrent inguinal hernia is difficult to understand anatomically, and its repair is often challenging [1]. Therefore, several guidelines [2,3,4] propose that repeat laparoscopic repair procedures should be performed by a surgeon with sufficient procedural skill.

Furthermore, in the treatment of incarcerated and strangulated inguinal hernias, an open approach is recommended because no other additional skin incision is needed when performing intestinal resection. However, various judgments should be made for each case.

We successfully treated a patient with recurrent incarcerated hernia following repair with the transabdominal preperitoneal (TAPP) approach with hybrid surgery combining the extraperitoneal approach with mesh plug repair.

Case presentation

Patient

A man in his 70 s.

When he was in his 60 s, the patient underwent surgery for a left inguinal hernia [TAPP method, Japanese Hernia Society (JHS) classification [2] II-1, Bard® 3D MAX Light, M size].

He visited the emergency outpatient services of our hospital due to abdominal pain and vomiting 2 h prior. His abdomen was swollen and tense. In the left inguinal region, tender golf ball-sized swelling was noted. Abdominal and pelvic computed tomography (CT) findings showed a recurrent left inguinal hernia with complications of small intestine incarceration and obstruction. Ascites was observed within the hernia sac.

Upon suspicion of incarcerated hernia, manual reduction was attempted. However, reduction could not be achieved. Emergency surgery was adopted as the treatment policy.

Surgical findings

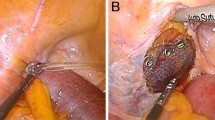

We judged that it was risky to insert the first port on the navel. Referring to the CT scan, we inserted the first port in the upper left abdomen for laparoscopy. Laparoscopic observation revealed the recurrence of left inguinal hernia (JHS classification Rec II-1), incarceration of the small intestine, and general dilatation of the bowel due to intestinal obstruction. Following pneumoperitoneum, the incarcerated small intestine spontaneously reduced. Mild hematoma was observed in the mesentery of the incarcerated bowel; however, there were no clear findings that suggested strangulation (Fig. 1). The mesh of the initial surgery was found to extend from near the root of inferior epigastric vessels to the medial umbilical fold (Fig. 2). The hernia orifice was found in Hesselbach’s triangle, and particularly severe scarring was noted on the medial side of the hernia orifice (Fig. 3). We assumed that the recurrence occurred as the first mesh was corrugated and shifted. Considering the difficulty involved in ensuring the visual field due to bowel dilatation using the TAPP method, we dissected the adhesions surrounding the hernia sac as much as possible using the TEP method (Fig. 4). In the extraperitoneal space, there was adhesions especially at the inner side of the hernia orifice, it was slightly difficult to treat adhesions at this site. Thereafter, we switched to mesh plug repair. The hernia sac could be easily identified and treated with Bard® Mesh Plug and an onlay patch. Upon re-examination of the intraperitoneal space, we confirmed that the hernia was repaired (Fig. 5), and no findings suggested strangulation in the bowel. The operative duration was 3 h and 40 min with minimal blood loss. The postoperative wound is presented in Fig. 6.

Postoperative progress

We did not observe any perioperative complications, and the subject was stable enough to be discharged on postoperative day 6. After rehabilitation, the subject was discharged on postoperative day 11. At the time of writing this report, at 10 months postoperatively, no signs of recurrence or infection were observed.

Discussion and conclusions

With regard to surgical procedures for recurrent hernia, few high-quality reports have recommended specific procedures. The presence or absence of preperitoneal detachment with prior surgery has the greatest impact on the selection of surgical procedure for recurrent hernia. The World Guidelines for Groin Hernia Management published as a draft by the HerniaSurge Group recommend anterior repair for recurrence following posterior repair, including laparoscopic surgery. Moreover, several guidelines also suggest that experienced practitioners select the surgical procedure based on comorbidities, form of recurrence and practitioner skill level [2,3,4,5].

The advantage of using laparoscopy for recurrent inguinal hernia is that observation of the inguinal region with laparoscopy provides useful information on recurrence characteristics (e.g., the location of the hernia orifice and the previous mesh). It is important to confirm the dislocation of the previously placed mesh, the positional relationship of the mesh to the hernia orifice, and the degree of adhesion to prevent re-recurrence [6]. Furthermore, observation after repair makes it possible to confirm the adequacy of deployment of the newly inserted mesh [7]. However, this information cannot be obtained enough using intraperitoneal observation alone. Therefore, we adopted the preperitoneal approach (i.e., TEP repair). We dissected around the hernia sac as much as possible with preservation of the vasculature with the TEP technique. We believe it is advantageous when switching to mesh plug repair because it enables identification and dissection of the hernia sac to be performed safely and easily.

Factors that affect the selection of surgical procedures for hernias include the presence or absence of bowel incarceration and strangulation. Evidence in support of laparoscopic surgery for patients with incarcerated and strangulated hernias is limited.

Even if the incarcerated hernia is spontaneously reduced, intraperitoneal observation is recommended to assess the incarcerated organ [8]. At present, there are no established treatment methods for strangulated hernia. In patients with irreversible blood flow impairment in the incarcerated bowel and those requiring bowel resection and anastomosis, the approach and mesh use remain controversial [9]. To our knowledge, no RCTs have compared the two procedures, TAPP and TEP repair in incarcerated or strangulated hernia. We believe that TEP repair is useful because it enables the separation of the clean operative field and contaminated operative field, and even if concurrent bowel obstruction and the space within the peritoneum is limited, surgery can be performed easily with a relatively good visual field [10].

For recurrent incarcerated and strangulated hernias, the optimal treatment should be selected for each case, such as the details of previous surgery, skill level of the practitioner, and general condition of the patient. Based on our experience, we believe that performing concurrent TEP repair in the hybrid method is useful for dissecting around the hernia sac and reduces the risk of repeat recurrence. For cases of incarcerated and strangulated hernia, we also consider the method to be useful for securing the visual field and for isolating the noncontaminated area when performing contaminated surgery.

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Abbreviations

- TEP:

-

Totally extraperitoneal

- TAPP:

-

Transabdominal preperitoneal

- JHS:

-

Japanese Hernia Society

- CT:

-

Computed tomography

References

Burcharth J. The epidemiology and risk factors for recurrence after inguinal hernia surgery. Dan Med J. 2014;61:B4846.

Inguinal Hernia Treatment Guideline. The Japan Hernia Society. 2015.

Bittner R, Arregui ME, Bisgaard T, Dudai M, Ferzli GS, Fitzgibbons RJ, et al. Guidelines for laparoscopic (TAPP) and endoscopic (TEP) treatment of inguinal hernia [International Endohernia Society (IEHS)]. Surg Endosc. 2011;25:2773–843.

HerniaSurge Group. International guidelines for groin hernia management. Hernia. 2018;22:1–165.

The HerniaSurg Group. World guidelines for groin hernia management. 2016. http://www.herniasurge.com.

Hideaki M, Hideaki A, Masanao I, et al. Laparoscopy-assisted hernioplasty for a recurrent inguinal hernia after mesh plug repair. J Jpn Surg Assoc. 2002;63:219–22.

Hoshino A, Yamaguchi K, Kawamura Y, et al. Transabdominal preperitoneal repair for recurrent groin hernia. Gastroenterol Surg. 2018;41:381–9.

Hayashi M, Tochii K, Kokubo K, Takahashi K, Matsumoto M. Delayed stenosis of the small intestine after surgery via the femoral approach combined with laparoscopy for an incarcerated femoral hernia. J Jpn Surg Assoc. 2014;75:1292–5.

Sartelli M, Coccolini F, van Ramshorst GH, Campanelli G, Mandalà V, Ansaloni L, et al. WSES guidelines for emergency repair of complicated abdominal wall hernias. World J Emerg Surg. 2013;8:50.

Gass M, Scheiwiller A, Sykora M, Metzger J. TAPP or TEP for recurrent inguinal hernia? Population-based analysis of prospective data on 1309 patients undergoing endoscopic repair for recurrent inguinal hernia. World J Surg. 2016;40:2348–52.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Nature Research Editing Service (http://bit.ly/NRES_BS) for English language editing.

Funding

Not applicable.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

YO was responsible for collecting the data for the patient, follow-up, preparation of the manuscript, and wrote and edited the manuscript. YO and NH performed the operation. NH obtained the patient’s written informed consent to publish the report. NH, SM, RK, YI, AK, WF and KY contributed to the review and editing of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for publication of this case report and any accompanying images.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Ooe, Y., Horikawa, N., Miyanaga, S. et al. Management of an obstructed recurrent inguinal hernia using a hybrid method: a case report. BMC Surg 21, 48 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12893-021-01069-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12893-021-01069-7