Abstract

Background

The indication for operative treatment of clavicular fractures with bone shortening over 2 cm is much debated. Correct measurement of clavicular length is essential, and reliable measures of clavicular length are therefore highly requested by clinical decision-makers. The aim of this study was to investigate if three commonly scientifically used measurement methods were interchangeable to each other.

Methods

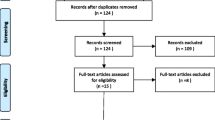

A retrospective study using radiographs collected as part of a previous study on clavicular fractures. Two independent raters measured clavicle shortening on 60 patients using conventional radiographs on two separate sessions. The two measurement methods described by Hill et al. and Silva et al. were used on unilateral pictures. Side difference measurements according to Lazarides et al. were made on panoramic radiographs. The measurements were analyzed using intraclass correlation, Weir’s protocol for Standard error of measurement (SEM) and minimal detectable change (MDC), and Bland-Altman plots.

Results

None of the methods were directly interchangeable. The side difference method by Lazarides et al. was the most reliable of the three methods, but had a high proportion of post-fracture bone lengthening that indicated methodological problems. The Hill et al. and Silva et al. methods had high minimal detectable change, making their use unreliable.

Conclusion

As all three measurement methods had either reliability or methodological issues, we found it likely that differences in measurement methods have caused the differences in clavicular length observed in scientific studies.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Clavicular fractures are common and represent approximately 2.5–7% [1] of all fractures. Depending on the site and severity of the fracture, they are predominately treated non-operatively with good results. Various relative operative indications exist for mid-clavicular fractures, one such indication being post-fracture bone shortening above 20 mm0, [2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9] as conservative treatment has been linked to adverse outcome in terms of decreased strength and overhead motion of the arm. This is much debated, however, as a handful of studies have not been able to confirm these adverse results [10,11,12,13].

Essential for the correct treatment and classification of shortening is accurate measurement. However, there is no standardized method of measuring shortening, and different methods seem to have been used equivalently [3, 7]. The most commonly used measurement methods can be divided into two concepts: fragment overlap [3, 14] and side difference [7]. These two measurement approaches appear to be very different as they build on different concepts. The fragment overlap methods build on the principle of drawing a perpendicular line between the lateral and medial fragment. Shortening is then defined as distance from this line to the tip of the upper fragment. The side difference method uses the uninjured clavicle as reference. Shortening is then the difference in length from the injured clavicle length.

It is therefore very likely that measurement method used could influence the conclusion on shortening, and in the end be the cause for the debate about clavicular bone shortening. A previous study comparing different methods to measure shortening of healed clavicular fractures have shown that the estimated shortening varied significantly according to the method used [15]. Whether the estimated shortening on initial radiographs of acute displaced clavicular fractures is influenced by the measurement method is unknown. To investigate if the choice of measurement method could explain the different conclusions of peer-reviewed studies, we designed a validation study.

The aim of the current study was to compare three methods for measuring acute post-fracture mid-clavicular bone shortening with the objectives of describing measurement results by each method, estimating the inter- and intra-observer reliability and the inter-method agreement. The three methods were Silva et al. [14] and Hill et al. [3] (both based on the principles of fragment overlap) and Lazarides et al. [7](based on the principles of side difference).

Ethical considerations

The study was a retrospective comparative study using radiographs that were collected as part of a not yet published study on clavicular fractures [ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT01483482]. The original study had been approved by the National Danish Data Registry (reference number: 2011–41-6031). Approval by the local ethical committee of the capital region was unnecessary.

Method and power calculation

A power calculation was done using the formula, limits of agreement = \( \sqrt{\frac{3}{n}}S \) = 16, where s is the standard deviation of the measurement difference between methods and n is the sample size. We wanted to estimate the limits of agreement within a margin of +/− 2.5 mm. We set the s as the normal anatomical standard deviation for clavicle length of approximately 10 mm [16] and found the number needed was 48 patients.

Of the 105 radiographs from the original study [ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT01483482], 25 were excluded due to non-accessible x-rays in the database and a further 20 were excluded because of incomplete panorama radiographs. The final study thus included 60 radiographs (60 patients) with acutely displaced clavicular fractures.

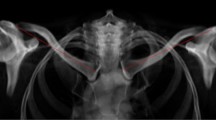

Two raters measured the radiographs in five separate sessions at least two weeks apart. The raters were experienced junior consultants in orthopedics and trauma medicine who viewed the original articles for method instructions and agreed on how each measure was attained. During the sessions, the original studies were consulted for guidance if the raters were in doubt about the methodology, and the raters were blinded to each other’s results. The single anterior posterior radiographic view was used for the methods described by Silva et al. and Hill et al., while the panorama view including both clavicles was used for the method described by Lazarides et al. (Fig. 1). Length was measured using the available software (Carestream health inc. Verona street 150, Rochester NY 14608) which was noted in centimeters and converted to millimeters by the authors. For each radiograph, date and time were noted to ensure that the same radiograph was measured consecutively.

The three methods for measuring post-fracture clavicular length compared in this study. Silva [14]: a line is drawn through the middle of each fragment. From each middle line, a perpendicular line between each fragment is drawn. Bone shortening is defined as the distance between the perpendicular lines on single anterior-posterior view. Hill [3]: a line is drawn from the bottom fragment perpendicular to the top fragment. Bone shortening is defined from the line to the tip of the top fragment on single anterior-posterior view. Lazardis [7]: the length of each clavicle is measured. Bone shortening is defined as uninjured clavicle length minus injured clavicle length on a panorama view

Analysis

Statistical analysis was performed with use of STATA software (version 13.1; STATACORP, College Station, Texas). Simple descriptive statistics were used. Measurement distributions were assessed after dividing into three groups: lengthening (over 0 mm), neutral (between 0 mm and −19 mm) or clinical significant shortening (over 20 mm).

For comparison of reliability, we used the protocol described by Weir [17]. Inter-rater comparison used the second measurements made by each rater. The bone shortening intra-class correlation (ICC) was calculated for all three methods. A one-way random level for confidence was used for intra-observer reliability (one rater) while a two-way random level of confidence was used for inter-observer reliability (two raters). The obtained ICC values were used to calculate SEM, Standard error of measurement [SEM = SD × √ (1– ICC)] describing the given error for each measurement method. Afterwards MDC, minimal detectable change, was calculated with the use of SEM in the formula (MDC = 1.96 × √2 × SEM) to estimate the smallest given change each method would be able to detect.

Agreement between methods was visualized using Bland-Altman plots [18] estimating the convergent validity and limits of agreement comparing all three methods as reference.

Results

The final study group had a median age of 36.5 years (min. 18, max. 62) with 51 men and 9 women. Mean total length of the pooled all measurements clavicle for the injured unilateral clavicle was 160.8 mm (SD 14.9). For the pooled all measurements panorama radiographs, uninjured clavicle length was 168.2 mm (SD 12.8 mm) and injured 160.4 mm (SD 14.4 mm).

The plot of the results (Fig. 2) from all 240 measurements (n = 60) from each method showed visually that the side difference method by Lazarides et al. was very different from the two fragment overlap methods, which were more similar to each other. The method by Lazarides et al. also found more patients with lengthening and fewer with shortening over 20 mm. Histograms (Fig. 3) showed that all three methods had a normal distribution pattern for the 240 measurements (n = 60). The Silva et al. method gave a mean shortening of −20 mm (SD: 13 mm), the Hill et al. method had a mean shortening of −22 mm (SD: 12 mm), and the Lazarides et al. method had a mean shortening of −8 mm (SD: 12).

Plot of shortening as measured by the three respective measurement methods. Reference lines show 0 and −20 mm shortening. The side difference method by Lazarides et al. produced a large proportion of patients with lengthening of the bone after a fracture, while the Silva et al. and Hill et al. methods had a large proportion of patients with shortening over the clinical significant −20 mm

Histogram of shortening as measured by the three respective methods. The side difference method by Lazarides et al. found that 19% of all measurements had either lengthening or zero shortening. In comparison, the fragment overlap methods by Silva et al. and Hill et al. found that 4–5% of the measurements had either lengthening or zero shortening

When the measurements were divided into lengthening (over 0 mm), neutral (between 0 mm and −19 mm) or shortening (over 20 mm), the Silva et al. method showed that 5% of the measurements had lengthening, 43% were neutral and 52% had shortening. The Hill et al. method showed that 4% had lengthening, 31% were neutral and 65% had shortening. The Lazarides et al. method showed that 19% of the measurements had lengthening, 65% were neutral and 16% had shortening.

The three methods showed comparable ICC for both inter- and intra-observer reliability, with slightly better results for the Lazarides et al. method (Table 1) The mean bone shortening was comparable between Silva et al. and Hill et al., while Lazarides et al. had significantly shorter mean bone shortening. Standard error of measurement (SEM) was comparable for all three methods. The Silva et al. and Hill et al. methods had the largest minimal detectable change (MDC), while the method by Lazarides et al. had the smallest MDC of the three methods.

Using Bland-Altman plots stating limit of agreement and mean disagreement, the fragment overlap methods (Silva et al. and Hill et al.) showed good consistency with each other but with very wide limits of agreement (Table 2, Fig. 4). Both Silva et al. and Hill et al. had very poor agreement with Lazarides et al., both in mean difference and limits of agreement (Table 2, Fig. 4).

Bland-Altman plots of the three methods plotted against each other. Top: The Silva method versus the Hill method. The Bland Altman plot shows good agreement between the two methods but with reasonably wide limits of agreements. No graph is superior. Middle: the Silva method versus Lazarides method Bland Altman plots shows very poor agreement between the two methods as well as very wide limits of agreement. No graph is superior. Bottom: the Hill method versus Lazarides method. The Bland Altman plot shows very poor agreement between the two methods. Limits of agreement are very wide

Discussion

In this study comparing three previously described methods for defining bone shortening in acutely displaced mid-clavicular fractures, we found the side difference method by Lazarides et al. to differ substantially from the two fragment overlap methods, which showed good immediate comparability. Use of the side difference method resulted in more measurements showing lengthening and significantly fewer measurements with shortening over 20 mm. The side difference method also showed the best reliability based on standard error of measurement (SEM) and minimal detectable change (MDC). The two fragment overlap methods had a high MDC making their clinical use questionable, despite a respectable SEM. The fragment overlap methods by Silva et al. and Hill et al. had comparable mean differences, but with extremely wide limits of agreement i.e. 95% confidence intervals, while the measurements done by the side difference method by Lazarides et al. not in any way was correlated to the other methods.

Our results indicate that the measurement method chosen is critical to the measurement of post-fracture clavicular bone shortening, and studies involving clavicular bone shortening should be read with this in mind. Until now, different measurement methods have been described as equivalent, but our results show there is a clear distinction. The simple descriptive statistics, graphs and analyses showed that the side difference method described by Lazarides et al. gave results that were very different from the fragment overlap methods described by Silva et al. and Hill et al. This is also to be expected from the difference in measurement concepts.

A similar pattern was seen when analyzing the reliability of the methods. The fragment overlap methods by Hill et al. and Silva et al. were comparable regarding the standard error of measurement (SEM) and minimal detectable change (MDC), but these methods had very wide MDC. This suggests that their clinical use is unreliable for measurements purposes, as the minimal clinically important length is set to 20 mm – and it would not help to change to a more arbitrary limit e.g. 25 mm. In comparison, the Lazarides et al. side difference method showed a much better SEM and MDC, which should make it more clinically relevant. However, in this study we found methodological issues with the side difference method as it showed three times as many measurements with post-fracture lengthening of the bone than the fragment overlap methods. Lengthening after a fracture should theoretically be unlikely, as muscle pull would always tend to shorten the bone. These findings are probably a consequence of previously stated methodological issues with the side difference method, as it relies on the concept of bilateral length symmetry within individuals. A previous study have shown that this is not always the case, and clavicles follow a randomly distributed left and right length difference ranging between 0 and 15 mm [19]. Consequently, the bone lengthening observed in this study could be attributed to an underlying methodological error. Ultimately, even the use of the side difference method by Lazarides et al. is therefore problematic.

The limitations of this study are that measurements were done consecutively and only two raters were used. Any mistake or misunderstanding of the measurement methods could possibly be aggravated over a larger series of measurements. We tried to avoid this by regularly consulting the original description by Hill et al. or Silva et al. if in doubt. Our intra-class correlation was in fact slightly higher than results reported by Silva et al. [14] indicating that we were able to minimize this bias. A final limitation was that we had to exclude 45 of 105 available participants due to lack of images or errors on the radiographs. In this particular study, this was not of great importance as it was the rater agreement that was of interest and we managed to include 60 patients, which was well above our power calculation. We would not expect to see any significant change in the intra-class correlation if a higher number of participants were to be included. The strengths of this study are that is the first of its kind to compare intra-class correlation and to quantify SEM and MDC within and between clavicular bone shortening measurement methods.

Conclusion

Our findings show that it is very likely that differences in measurement methods have caused the variation in results from studies on post-fracture clavicular bone shortening. Whether bone shortening results in adverse outcome is still subject to debate, but if used in a clinical setting it is important to have a reliable and accurate estimate. Based on our study, the side difference method by Lazarides et al. is the most accurate and reliable. However, as it relies on bilateral symmetry and identified a large proportion of patients as having bone lengthening rather than shortening, its use seems problematic. The two fragment overlap methods (described by Hill et al. and Silva et al.) appeared unreliable, and their use cannot be recommended. In conclusion, our findings raise a new question as to which method should be used, when taking both scientific and clinical grounds into consideration.

Abbreviations

- ICC:

-

Intra Class Correlation

- LOA:

-

Limits of agreement

- MDC:

-

Minimal detectable change

- SEM:

-

Standard error of measurement

References

Robinson CM. Fractures of the clavicle in the adult. Epidemiology and classification. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1998;80:476–84.

Eskola A, Vainionpää S, Myllynen P, et al. Outcome of clavicular fracture in 89 patients. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 1986;105:337–8.

Hill J, McGuire M, Crosby L. Closed treatment of displaced middle-third fractures of the clavicle gives poor results. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1997;79:537–9.

Wick M, Müller EJ, Kollig E, Muhr G. Midshaft fractures of the clavicle with a shortening of more than 2 cm predispose to nonunion. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 2001;121:207–11.

McKee MD, Pedersen EM, Jones C, et al. Deficits following nonoperative treatment of displaced midshaft clavicular fractures. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2006;88:35–40. doi:10.2106/JBJS.D.02795.

Smekal V, Irenberger A, Struve P, et al. Elastic stable intramedullary nailing versus nonoperative treatment of displaced midshaft clavicular fractures-a randomized, controlled, clinical trial. J Orthop Trauma. 2009;23:106–12. doi:10.1097/BOT.0b013e318190cf88.

Lazarides S, Zafiropoulos G. Conservative treatment of fractures at the middle third of the clavicle: the relevance of shortening and clinical outcome. J Shoulder Elb Surg. 2006;15:191–4. doi:10.1016/j.jse.2005.08.007.

Postacchini R, Gumina S, Farsetti P, Postacchini F. Long-term results of conservative management of midshaft clavicle fracture. Int Orthop. 2010;34:731–6. doi:10.1007/s00264-009-0850-x.

Thormodsgard TM, Stone K, Ciraulo DL, et al. An assessment of patient satisfaction with nonoperative management of clavicular fractures using the disabilities of the arm, shoulder and hand outcome measure. J Trauma. 2011;71:1126–9. doi:10.1097/TA.0b013e3182396541.

Rasmussen JV, Jensen SL, Petersen JB, et al. A retrospective study of the association between shortening of the clavicle after fracture and the clinical outcome in 136 patients. Injury. 2011;42:414–7. doi:10.1016/j.injury.2010.11.061.

Oroko PK, Buchan M, Winkler A, Kelly IG. Does shortening matter after clavicular fractures? Bull Hosp Jt Dis. 1999;58:6–8.

Stegeman SA, de Witte PB, Boonstra S, et al. Posttraumatic midshaft clavicular shortening does not result in relevant functional outcome changes. Acta Orthop. 2015;86:545–52. doi:10.3109/17453674.2015.1040982.

Figueiredo GS de L, Tamaoki MJS, Dragone B, et al. Correlation of the degree of clavicle shortening after non-surgical treatment of midshaft fractures with upper limb function. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2015;16:151. doi:10.1186/s12891-015-0585-3.

Silva SR, Fox J, Speers M, et al. Reliability of measurements of clavicle shaft fracture shortening in adolescents. J Pediatr Orthop. 2013;33:e19–22. doi:10.1097/BPO.0b013e318287f73f.

Smekal V, Deml C, Irenberger A, et al. Length determination in midshaft clavicle fractures: validation of measurement. J Orthop Trauma. 2008;22:458–62. doi:10.1097/BOT.0b013e318178d97d.

McCormick WF, Stewart JH, Greene H. Sexing of human clavicles using length and circumference measurements. Am J forensic Med Pathol Off Publ Natl Assoc Med Exam. 1991;12:175–81.

Weir JP. Quantifying test-retest reliability using intraclass correlation coefficient and the SEM. J strength Cond Res. 2005;19:231–40.

Bland JM, Altman DG. Statistical methods for assessing agreement between two methods of clinical measurement. Lancet. 1986;1:307–10.

Cunningham BP, McLaren A, Richardson MMR. Clavicular length: the assumption of symmetry. Orthopedics. 2013; doi:10.3928/01477447-20130222-24.

Acknowledgements

Not Applicable.

Funding

This study was not funded externally.

Availability of data and materials

Upon publication, all datasets will be made available at the national library of Denmark. The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

PU, IB and AH was a major contributor for the collection of data. IB, LHF and AH were a major part in analyzing and interpreting the patient data. IB, LHF and AH were major contributors in writing the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The data used in this study were collected as part of a previous study, which had previously approved by the local ethical committee [ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT01483482]. The study was approved by the national Danish data registry as well. Informed consent had previously obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

Author Peter Muhareb Udby, Author Ilija Ban, Author Lars Henrik Frich, and Author Anders Thorsmark Høj declare that they have no conflict of interest nor competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Thorsmark, A.H., Muhareb Udby, P., Ban, I. et al. Bone shortening of clavicular fractures: comparison of measurement methods. BMC Musculoskelet Disord 18, 537 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12891-017-1881-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12891-017-1881-x