Abstract

Background

Law enforcement personnel have been recognized as having a high risk for several lifestyle-related health conditions which, in combination with the nature of their work (sedentary roles interspersed with intermittent high-intensity activity, shift work, and a high stress-load), can have a negative impact on their health. The aim of this study was to investigate the dietary habits and factors or barriers influencing these habits within a cohort of law enforcement personnel in the United States of America.

Method

Cross-sectional data were obtained via validated paper-based surveys being the Perceived Barriers to Healthy Eating, Food Choice Questionnaire and Rapid Eating Assessment for Participants, Short Version.

Results

A total of 159 participants (median age = 27 [range 19–60] years; 74% males) participated. Barriers to healthy eating included being busy and irregular working hours. Overall, 91% (n = 143) placed high importance on consuming nutritious food and 80% (n = 126) on food high in vitamins and minerals. A further 80% (n = 127) emphasized high protein content and 41% (n = 62) followed a high protein diet. Barriers to healthy eating included busy lifestyle (60%, n = 94), and irregular working hours (41%, n = 64). Overall, 80% (n = 127) were very willing to make changes in eating habits to be healthier.

Conclusion

Law enforcement officers know what they should eat and report convenience and health the most important factors guiding their food choices. Knowing this, officers find challenges putting good dietary practices into practice due to factors like a busy lifestyle and irregular work hours. Reportedly “very willing” to make changes in their eating habits to be healthier, future interventions should focus on how to effect changes to their eating habits as opposed to focussing on what to eat.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Law enforcement personnel have been recognized as being prone to obesity [1] and having a high risk for several lifestyle-related health conditions [2,3,4]. The nature of their work, including sedentary roles interspersed with intermittent high-intensity activity, shift work, and a high stress-load can have a negative impact on their health and performance [5,6,7]. These personnel should maintain a requisite level of physical fitness to optimize their concentration, performance and safety; and as such while a focus on nutrition strategies that promote good health are important, a broader focus that encompasses strategies that optimize nutrition for performance is also warranted. Despite this, little is known about law-enforcement personnel’s dietary intake.

In law enforcement personnel, several studies have captured the duties involved in law enforcement and the corresponding impact on health [5,6,7]. In addition, there have been several studies linking socio-cultural and occupational factors with body composition and/or physical fitness [8,9,10]. However, few studies have directly explored dietary intake for this population [11,12,13]. Briley et al. evaluated the efficacy of a nutrition education component of a wellness program (pre- and post-implementation data) however, the baseline diet was not detailed [11]. Mumford et al. surveyed officers in law enforcement agencies regarding physical activity patterns, job characteristics, substance use, critical incidents, job-related stress, personal health and healthcare usage [12] and used a two-item measure of fruit and vegetable consumption on a typical day. They reported ~ 17.2% of respondents ate over 5 serves of fruit and vegetables per day, with a higher intake positively correlated with self-reported health status [12]. To date – the most comprehensive dietary study in law-enforcement personnel was performed by Gibson et al. [13]. The researchers performed a large-scale cohort study of law enforcement personnel worldwide by analysing participant data extracted from the Airwave Health Monitoring Study [13]. The Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension (DASH) score was used to determine dietary quality and a 7-day food record for dietary intake. The study reported dietary intake data and identified that a poor DASH score was associated with other negative lifestyle behaviours (inactivity, smoking and TV viewing). Furthermore, long working hours and high job strain (in men) increased the odds of reporting a dietary intake associated with cardiometabolic risk. Finally, the SHIELD study assessed law-enforcement personnel fruit and vegetable consumption using the National Cancer Institute’s fruit and vegetable all-day screener with additional questions to assess frequency, amount of dietary fat and self-reported healthy eating [14]. Rather than reporting dietary intake per se, the study focussed on changes in dietary scores pre and post intervention. Similarly and more broadly, several studies have demonstrated the successful impact of health or nutrition promotion programs on health attitudes and behaviors for athletic teams, firefighters, and law enforcement personnel [14,15,16,17].

While full, accurate dietary assessments can be difficult in law enforcement personnel, gaining an understanding of dietary patterns and diet quality is useful and can inform nutrition interventions. Correspondingly, a greater understanding of the factors that influence dietary patterns and diet quality in law enforcement personnel is needed to further inform potential interventions [18]. In particular, the identification of barriers to the consumption of healthy foods must be identified in the design of effective behaviour change interventions [19,20,21]. Law enforcement personnel are known to have a range of challenges including shift work, overtime, and lack of structured breaks due to their nature of their work [5,6,7, 13, 22] hence understanding their perception of barriers is useful.

To the authors’ knowledge, no research has been undertaken exploring the factors that influence food choice, beliefs, and diet quality (as measured by REAPS-S) in law enforcement personnel. Broadly, this study will investigate the dietary habits and food choices of a cohort of law enforcement personnel including custody assistants, civilian jailers, sworn deputies and police officers, and reserve peace officers in the United States of America (USA). The specific aims of this study are 1) to explore self-reported barriers to optimised dietary intake; 2) to report participant perceptions of factors that influence food choice; and 3) perform a rapid assessment of diet quality and willingness to change in a cohort of law enforcement personnel. The surveys chosen are validated, brief surveys that are suitable for use by time-poor law enforcement personnel [23,24,25]. It is anticipated that this research will provide valuable information for nutrition, performance, and health promotion strategies that support behaviour change, as well as organizational and systematic changes and future research that support this high-risk population.

Methods

This single site, cross-sectional survey study was conducted in 2019 and evaluated data of law enforcement personnel in a large, metropolitan facility in the USA Cross-sectional data were obtained via validated paper-based surveys being the Perceived Barriers to Healthy Eating, Food Choice Questionnaire (FCQ) and Rapid Eating Assessment for Participants, Short Version (REAP-S). The questionnaires have been previously published [23,24,25] and are designed to measure perceived barriers/difficulties in eating a healthy diet, participants attitudes and beliefs on the factors that influence their dietary intake and a rapid first-choice dietary assessment indicating diet quality and willingness to change [23,24,25].

The Perceived Barriers to Healthy Eating questionnaire [24] was developed by a group of experts in attitudinal research and contains a list of 22 possible barriers for participants to select which they perceive as major difficulties in trying to eat a healthier diet. The Food Choice Questionnaire (FCQ) is a seminal tool which has been developed to measure multidimensional factors related to food choice at the individual level and through factor analysis health, mood, convenience, sensory appeal, natural content, price, weight control, familiarity and ethical concern emerged [23]. The questionnaire contains 36 questions and a five-point Likert Scale for responses ranging from ‘not important’ to ‘very important’. Since it was developed, the FCQ has been applied in a large number of countries from all continents [20], is used in a range of population groups [26,27,28]. The REAP-S was developed at the Albert Einstein College of Medicine of Yeshiva University and contains 13 questions regarding how often participants consume various foods or dietary patterns in an average week. There are three response categories of ‘usually/often’, ‘sometimes’, ‘rarely/never’ or ‘does not apply to me’ results indicating consumption frequency of various foods or dietary patterns. Survey scores provide an indicator of diet quality and the survey also asks how willing participants are to make changes in eating habits to be healthier; highlighting readiness to change.

Each of the surveys were provided to participants in a paper-based format to self-report following the obtainment of written informed consent. Ethics approval was provided by an International Review Board (IRB 15–074), and Bond University’s Human Research Ethics Committee (RO1927). The study has been reported according to STROBE guidelines [29] survey.

Participants were conveniently sampled; all law enforcement personnel present at a recruitment training unit over 20 weeks were invited to participate in the study. Three categories of personnel were captured: custody assistants or civilian jailers, sworn deputies and police officers and reserve peace officers. Inclusion criteria were a) adults aged ≥18 years, b) participants able to understand English, and c) participants provide voluntary consent. Participants were not required to declare medical conditions or health status but would have all passed a medical assessment to have been employed as law enforcement personnel.

Key demographic data were featured on the paper questionnaire, including self-reported height and weight which has been found to be accurate within a law enforcement population [30]. In addition, physical activity (resistance and endurance training frequency), and descriptive data on diets (diets followed, who prepares meals) were also collected. Height and weight were used to calculate body mass index via the following formula; weight (kg) / [height (m)]2 and classified as per the World Health Organization categories [31].

The validated paper-based survey responses were transferred to Statistical Package for the Social Science 25 (SPSS Statistics) where data were cleaned, categorized, and analysed. All continuous variables (age, weight, height) were not normally distributed hence are reported as median (range). Categorical variables were reported as frequency (n) and total percentage with all percentages referring to the valid data available for the variable. As a secondary analysis, a chi-square test was used for categorical variables to report associations between the different groups training; or Fisher’s exact test (two-sided) when results had ≥20% of cells with an expected count less than five. Significant difference and association were defined as p < 0.05 a priori. Survey results were synthesized and narratively discussed.

Results

A total of 159 participants (median age = 27 [range 19–60] years; 74% males) undergoing training in the USA participated in the study. This included 40 custody assistants or civilian jailers, 99 sworn deputies and police officers and 20 reserve peace officers representing a cross-section of law enforcement personnel. All 159 participants answered all questionnaires. Demographic related characteristics of grouped participants are displayed in Table 1. Comparisons between group demographics are in Additional file 1. With the exception of a significant difference (p < 0.001) in the median age of reserve peace officers 42 (22–60) years compared to custody assistants and sworn deputies (median age 25 (19–39) and 26 (20–50) years respectively); there were no other significant demographic differences between groups. All law enforcement personnel reported doing regular resistance and aerobic exercise with the majority doing ≥3 sessions per week (n = 108, 69% and n = 117, 73% respectively). There was a significant difference between groups as fewer reserve peace officers reported ≥3 sessions per week of resistance (n = 8, 40%) and aerobic (n = 10, 50%) exercise compared to custody assistants (n = 24, 62% and n = 25, 63% respectively) and sworn deputies (n = 76, 77% and n = 82, 82% respectively) (p = 0.036 for resistance and p = 0.004 aerobic respectively). Additionally, there were differences in who most often prepares meals with reserve peace officers taking responsibility less (n = 7, 35%) compared to custody assistants (n = 22, 57.9%) and sworn deputies (48, 51.1%) (p = 0.003).

Results on the perceived barriers to healthy eating can be seen in Table 2. Main barriers included busy lifestyle (60%, n = 94), irregular working hours (41%, n = 64), lengthy food preparation (35%, n = 55), price of healthy food (32%, n = 51) and cooking skills (30%, n = 48). Additional file 1 features between-group differences.

Results from The FCQ can be seen in Table 3. The majority of participants placed high importance on consuming nutritious food that keeps them heathy and is high in vitamins and minerals (91%, n = 143 and 80%, n = 126 respectively), as well as having a high protein content (80%, n = 127) (Table 3). Nearly half of participants followed a high protein diet (41%, n = 62). (Table 1). Of those that report following a high-protein diet only 4 participants reported usually/often eating more than 8 oz of meat a day (6.5%, n = 4). Overall, convenience and health were the most important factors influencing food choice (Table 3).

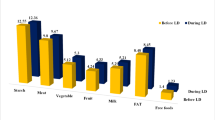

Results from the REAP-S survey including intake of core food groups, discretionary foods, and dietary patterns can be seen in Table 4. Scores from the REAP-S varied with 20% scoring between 19 and 27 (n = 32), 70% scoring 28–34 (n = 112) and 10% scoring 35–37 (n = 15). When asked ‘how willing are you to make changes in your eating habits in order to be healthier?’ the majority reported being very willing (80%, n = 127) followed by 14% willing (n = 22), 4% neutral (n = 7), 1% not very willing (n = 1) and 1% not willing at all (n = 2).

Discussion

Several studies have demonstrated the successful impact of health and nutrition promotion programs on health attitudes and behaviours for athletic teams, firefighters, and law enforcement personnel [14,15,16,17]. However, to effectively target nutrition interventions for law enforcement personnel, it is important that they are tailored specifically for the requirements of this high-risk population. This study provides insight into the factors that influence food choice, perceived barriers to healthy eating, dietary patterns, and willingness to change in law enforcement personnel undergoing training.

Firstly, and importantly, the majority of law enforcement personnel in this study reported being “very willing” to make changes in their eating habits to be healthier (80%, n = 127). However, qualitative studies within law enforcement officers found they believed their attempts to make healthier dietary changes were often sabotaged by the “nature of the job” including irregular work hours and unpredictable events [32]. Therefore, well-intentioned nutrition programs that instruct personnel on what they should eat as a base without a practical and tailored approach may not be successful. Instead, focusing on how to change is beneficial, and is part of the premise of beneficial programs such as the SHIELD program in law enforcement officers [14]. The team-based health promotion program was found to be feasible and effective at 6 months in improving diet across a range of variables (e.g. fruit and vegetable consumption and healthy eating) and in improving other health-related variables (e.g. sleep quality and quantity and stress levels). Overall, the program was feasible, effective, and durable for improving dietary changes.

While education is an important strategy for optimizing dietary intake, few law enforcement personnel identified not knowing enough about healthy eating as a barrier (n = 46, 29%). While the focus of the study was not on dietary intake per se; diet quality was indicated from the REAP-S. Twenty percent scored between 19 and 27 (n = 32) indicating lower diet quality, 70% scored from 28 to 34 (n = 112) and 10% scored 35–37 (n = 15) indicating a higher diet quality. Interestingly, it has been shown that perceived diet quality in American adults is associated with actual diet quality [33]. These findings suggest that while law enforcement personnel may have an awareness of what they should be eating, they may not always put this knowledge into practice. For example, the majority of participants placed a high importance on consuming nutritious food that kept them heathy and was high in vitamins and minerals (91%, n = 143 and 80%, n = 126 respectively), however their fruit and vegetable intake were low with more than half reporting ‘usually’ or ‘sometimes’ eating less than two serves a day (n = 105, 66% and n = 100, 65% respectively). This intention-behaviour gap may highlight that focusing on factors beyond nutrition knowledge that enable behaviour change (e.g. time management and organization, quick-healthy foods) may be important.

Collectively factors of convenience were reported as the most influential over food choice, and barriers to healthy eating included being busy and irregular working hours (n = 64, 41% and n = 94, 60% respectively). These food choice behaviours were expressed in the personnel’s dietary patterns; for example, 57% of respondents skipped breakfast often or sometimes (n = 91) and similarly, over half of the participants reported often or sometimes eating four or more meals from sit-down or take out restaurants (52%, n = 83). Law enforcement personnel are subject to shift work, overtime and often do not have structured breaks due to their nature of their work. As a result, law enforcement personnel may not adhere to conventional mealtimes. In addition, they may have an increased reliance on snacking and take-away food which include proportionally higher quantities of sweet and savory bakery products, soft drinks, juices and other non-alcoholic beverages compared to eating at home [34]. Interestingly, of the individuals who reported that they were responsible for their meal preparation (n = 77, 48.4%), only 5% reported eating out often compared to 46% who reported that when their partner cooked and 56% when a family member cooked. This reinforces a benefit for law enforcement personnel to be actively involved in their own food preparation, which may translate to better food preparation knowledge and organization.

While food choices reported by law enforcement personnel are relatively in line with nutritional recommendations within the USA, targeted support for this population is warranted. Considering that this population is at increased risk of several lifestyle-related health conditions, has increased physical requirements due to the demanding physical profession, and requires concentration in high-stress situations, optimizing dietary intake is of high importance as is maintain physical fitness. Law enforcement is a demanding profession and can place physical stress on personnel as they may be required to push, pull, lift, carry, or drag objects or people at any time during their shift [22]. Furthermore, daily tasks are often performed whilst carrying and wearing an external load that can weight around 10 kg [35]. In order to perform these physical tasks effectively, especially while wearing this external load, police officers are required to have a requisite amount of physical fitness [36, 37]. Considering this, while all law enforcement personnel within this study reported doing regular resistance exercise and aerobic exercise with the majority doing ≥3 sessions per week (n = 108, 69% and n = 117, 73% respectively), several dietary behaviours would not be considered optimal from a performance perspective. For example, a proportion of personnel rarely consumed more than 8 oz of protein-containing foods per day (n = 23, 15%) and the majority usually or sometimes consumed less than two serves of dairy-contain foods per day (n = 115, 73%); despite the majority believing protein intake was important or very important. When asked if they followed a special diet, 14% of participants reported following a low-carb diet (n = 22), 9% a no sugar diet (n = 13) and 7% a low-calorie diet (n = 12); indicating a tendency for some participants to eliminate food groups. Suboptimal dietary energy intake, and corresponding decreases in macro and micronutrients, are likely to influence performance in law enforcement personnel undergoing training [38, 39]. Furthermore, conscious restriction is often employed to control body weight however, imbalances in macronutrients may stimulate regulatory signals in the body, leading to overeating [40,41,42]. Where this dietary restriction is excessive or is coupled with concerning dietary beliefs and behaviours, an individualized approach with a dietitian or health professional is warranted.

There are several published team-based health and nutrition promotion programs supporting this population or similar population groups. Some reported topics included how to replace unhealthy fast food with healthy alternatives i.e. “a fast food makeover”, how to shop and cook healthy on a budget, how to reduce calories in snacks, lunches that can be brought from home “brownbag makeover” and counselling [14, 17, 43]. Additional strategies that have been reported have included time management or motivational tools including reminders, self-monitoring and reinforcement [43]. These types of strategies are supported by the current study. In addition, at a systematic or organizational level, further strategies for this workforce may include vehicle design and support for food and drink, choice architecture, healthy on-site food service provision and agreements/discounts with local healthy cafes and restaurants.

Strengths and limitations

The main strength of this study is the comprehensive and rigorous data collection via different validated surveys providing a broader description of diet pattern, diet quality, beliefs and motives as well as current barriers to healthy eating within a cohort of law enforcement personnel in the USA. With greater insight into these habits, tailored interventions at an individual and systematic/organizational level can be designed thereby increasing the chance of effectively initiating, and potential maintaining, enhanced nutrition behaviours. Noting this strength, several limitations require consideration. The current study was a single site study of law enforcement personnel undergoing training which can impact on its generalizability, for example its findings may not be applicable to law enforcement personnel in rural areas, in specialist roles, or after longer periods of service. To mitigate this limitation, the study does provide key information to inform future studies or interventions. A convenience sample was required due to difficulties capturing data from this population and the lack of current research in the area. While the study was undertaken in a relatively small sample size which did not support between-group analyses; it was undertaken in a group that are not commonly studied due to access and time constraints and featured a high response rate. While care was taken to choose appropriate tools, the surveys were not directly validated for this population. Though the validated tools are designed for self-reporting, some components may have been inaccurate or subject to biases. For example, BMI was included to provide demographic information on the personnel, but its limitations for an active population are acknowledged. To the authors’ knowledge, the validated studies are the best available for the population being studied at the time of data collection.

Conclusion

In law enforcement, enhancing officer physical performance, health, and safety, as well as injury mitigation and management, is important and suboptimal nutrition can directly threaten these factors. This study aimed to investigate the readiness to change, dietary habits, factors that influence food choice, and barriers to healthy eating in a cohort of USA law enforcement personnel undergoing training. This research provides descriptions of the habits, barriers and factors influencing healthy eating of law enforcement personnel and highlighted several dietary and behavioural areas of concern that are specific to this high-risk group. Practically, the study has supported that; 1) Nutrition and health programs should recognize and support law enforcement personnel’s motivation and readiness to change. 2) Nutrition and health programs can include content to enhance knowledge; but this should be supported by practical strategies that support behaviour change and address reported barriers to health eating i.e. focusing on how to change is beneficial. 3) While individual responsibility is important, systemic, and organizational approaches are important as some barriers to health eating (e.g. shift work, access to good food issues) are outside of the law enforcement personnel’s control.

Further qualitative and quantitative research would be beneficial to further support the development of targeted nutrition programs and strategies for law enforcement personnel. For example, increased periods of service or decreasing physical activity may impact readiness to change, food behaviours, factors that influence food choice, and barriers to healthy eating for law enforcement personnel. In addition, while not an exhaustive list, exploring differences in gender, age, rural versus metropolitan, roles/ranks, or responses in periods of heightened stress may be useful. This research has provided valuable information for nutrition, performance, and health promotion strategies that support behaviour change, as well as organizational and systematic changes that support this high-risk population.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Change history

11 November 2020

In the original publication, the heading "Background" in the Abstract was spelt incorrectly. The article has been updated to rectify the error.

Abbreviations

- USA:

-

United States of America

- FCQ:

-

Food Choice Questionnaire

- REAP-S:

-

Rapid Eating Assessment for Participants – shortened version

- IRB:

-

International Review Board

- STROBE:

-

Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology

- SPSS:

-

Statistical Package for the Social Science

- SHIELD:

-

Safety & Health Improvement: Enhancing Law Enforcement Departments

References

Gu JK, Charles LE, Burchfiel CM, Fekedulegn D, Sarkisian K, Andrew ME, et al. Long work hours and adiposity among police officers in a US northeast city. J Occup Environ Med. 2012;54(11):1374–81.

Violanti JM, Burchfiel CM, Hartley TA, Mnatsakanova A, Fekedulegn D, Andrew ME, et al. Atypical work hours and metabolic syndrome among police officers. Arch Environ Occup Health. 2009;64(3):194–201.

Violanti JM, Burchfiel CM, Miller DB, Andrew ME, Dorn J, Wactawski-Wende J, et al. The Buffalo cardio-metabolic occupational police stress (BCOPS) pilot study: methods and participant characteristics. Ann Epidemiol. 2006;16(2):148–56.

Yoo H, Franke WD. Sleep habits, mental health, and the metabolic syndrome in law enforcement officers. J Occup Environ Med. 2013;55(1):99–103.

Vila BDK. Tired cops: the prevalence and potential consequences of police fatigue. National Institute Justice J. 2002;248:16–21.

Hem E, Berg AM, Ekeberg Ø. Suicide in Police—A Critical Review. Suicide Life Threat Behav. 2001;31(2):224–33.

Rajaratnam SM, Barger LK, Lockley SW, Shea SA, Wang W, Landrigan CP, et al. Sleep disorders, health, and safety in police officers. Jama. 2011;306(23):2567–78.

Sörensen L, Smolander J, Louhevaara V, Korhonen O, Oja P. Physical activity, fitness and body composition of Finnish police officers: a 15-year follow-up study. Occup Med (Oxford, England). 2000;50(1):3–10.

Boyce RW, Jones G, Lloys G, Boone E. A longitudinal observation of police: body composition changes over 12 years with gender and rance comparisons. J Exerc Physiol Online. 2008;11(6):1–11.

Lagestad P, Van Den Tillaar R. A comparison of training and physical performance of police students at the start and the end of three-year police education. J Strength Cond Res. 2014;28(5):1394–400.

Briley ME, Montgomery DH, Blewett J. Dietary intakes of police department employees in a wellness program. J Acad Nutr Diet. 1990;90(1):65–8.

Mumford EA, Taylor BG, Kubu B. Law enforcement officer safety and wellness. Police Q. 2015;18(2):111–33.

Gibson R, Eriksen R, Singh D, Vergnaud A-C, Heard A, Chan Q, et al. A cross-sectional investigation into the occupational and socio-demographic characteristics of British police force employees reporting a dietary pattern associated with cardiometabolic risk: findings from the airwave health monitoring study. Eur J Nutr. 2017;57(8):2913–26.

Kuehl KS, Elliot DL, Goldberg L, MacKinnon DP, Vila BJ, Smith J, et al. The safety and health improvement: enhancing law enforcement departments study: feasibility and findings. Front Public Health. 2014;2:38.

Goldberg L, MacKinnon DP, Elliot DL, Moe EL, Clarke G, Cheong J. The adolescents training and learning to avoid steroids program: preventing drug use and promoting health behaviors. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2000;154(4):332–8.

Elliot DL, Goldberg L, Moe EL, Defrancesco CA, Durham MB, Hix-Small H. Preventing substance use and disordered eating: initial outcomes of the ATHENA (athletes targeting healthy exercise and nutrition alternatives) program. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2004;158(11):1043–9.

Elliot DL, Goldberg L, Kuehl KS, Moe EL, Breger RKR, Pickering MA. The PHLAME (promoting healthy lifestyles: alternative models’ effects) firefighter study: outcomes of two models of behavior change. J Occup Health Psychol. 2007;49(2):204–13.

Sanders D. Success factors in community-based nutrition Programmes. Food Nutr Bull. 1999;20(3):307–14.

Steptoe A, Pollard TM, Wardle J. Development of a measure of the motives underlying the selection of food: the food choice questionnaire. Appetite. 1995;25(3):267–84.

Cunha LM, Cabral D, Moura AP, De Almeida MDV. Application of the food choice questionnaire across cultures: systematic review of cross-cultural and single country studies. Food Qual Prefer. 2018;64:21–36.

Plichta M, Jezewska-Zychowicz M, Małachowska A. Relationship between psychosocial impairment, food choice motives, and Orthorexic behaviors among polish adults. Nutrients. 2020;12(5):1218.

Locher JL, Ritchie CS, Roth DL, Sen B, Vickers KS, Vailas LI. Food choice among homebound older adults: motivations and perceived barriers. J Nutr Health Aging. 2009;13(8):659–64.

Dellava JE, Hamer RM, Kanodia A, Reyes-Rodríguez ML, Bulik CM. Diet and physical activity in women recovered from anorexia nervosa: a pilot study. Int J Eat Disord. 2011;44(4):376–82.

Spence M, Livingstone MBE, Hollywood LE, Gibney ER, O’Brien SA, Pourshahidi LK, et al. A qualitative study of psychological, social and behavioral barriers to appropriate food portion size control. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2013;10(1):92.

Kearney M, Gibney M, Martinez J, De Almeida M, Friebe D, Zunft H, et al. Perceived need to alter eating habits among representative samples of adults from all member states of the European Union. Eur J Clin Nutr. 1997;51:S30.

Dawes JJ, Orr RM, Siekaniec CL, Vanderwoude AA, Pope R. Associations between anthropometric characteristics and physical performance in male law enforcement officers: a retrospective cohort study. Ann Occup Environ Med. 2016;28(1):26.

Kearney JM, McElhone S. Perceived barriers in trying to eat healthier--results of a pan-EU consumer attitudinal survey. Br J Nutr. 1999;81(Suppl 2):S133–7.

Segal-Isaacson CJ, Wylie-Rosett J, Gans KM. Validation of a short dietary assessment questionnaire: the rapid eating and activity assessment for participants short version (REAP-S). Diabetes Educ. 2004;30(5):774–81.

Von Elm E, Altman DG, Egger M, Pocock SJ, Gøtzsche PC, Vandenbroucke JP. The strengthening the reporting of observational studies in epidemiology (STROBE) statement: guidelines for reporting observational studies. Ann Intern Med. 2007;147(8):573.

Dawes J, Lockie R, Kukic F, Cvorovic A, Orr R, Kornhauser C, et al. Accuracy of self-reported height, body mass and derived body mass index in a group of United States law enforcement officers. J Criminalistics Law. 2019;24 doi: https://doi.org/10.5937/nabepo24-21191.

World Health Organization. Obesity: preventing and managing the global epidemic. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2000.

Ramey SL, Downing NR, Knoblauch A. Developing strategic interventions to reduce cardiovascular disease risk among law enforcement officers: the art and science of data triangulation. AAOHN J. 2008;56(2):54–62.

Powell-Wiley TM, Miller PE, Agyemang P, Agurs-Collins T, Reedy J. Perceived and objective diet quality in US adults: a cross-sectional analysis of the National Health and nutrition examination survey (NHANES). Public Health Nutr. 2014;17(12):2641–9.

Naska A, Katsoulis M, Orfanos P, Lachat C, Gedrich K, Rodrigues SSP, et al. Eating out is different from eating at home among individuals who occasionally eat out. A cross-sectional study among middle-aged adults from eleven European countries. Br J Nutr. 2015;113(12):1951–64.

Baran K, Dulla J, Orr R, Dawes JJ, Pope R. Duty loads carried by the LA sheriff's department deputies. J Australian Strength Conditioning Res. 2018;26(5):34–8.

Lockie RG, Dawes JJ, Balfany K, Gonzales CE, Beitzel MM, Dulla JM, et al. Physical fitness characteristics that relate to work sample test battery performance in law enforcement recruits. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2018;15(11):2477.

Orr R, Pope R, Stierli M, Hinton B. Grip strength and its relationship to police recruit task performance and injury risk: a retrospective cohort study. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2017;14(8):941.

O'Leary TJ, Wardle SL, Greeves JP. Energy deficiency in soldiers: the risk of the athlete triad and relative energy deficiency in sport syndromes in the military. Front Nutr. 2020;7(142):1–18.

Thomas DT, Erdman KA, Burke LM. Nutrition and athletic performance. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2016;48(3):543–68.

Simpson SJ, Raubenheimer D. Obesity: the protein leverage hypothesis. Obes Rev. 2005;6(2):133–42.

Flatt JP. The difference in the storage capacities for carbohydrate and for fat, and its implications in the regulation of body weight. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1987;499:104–23.

Birkenhead KL, Slater G. A Review of Factors Influencing Athletes' Food Choices. Sports Med (Auckland, NZ). 2015;45(11):1511–22.

Haynes R, McDonald HP, Garg A, Montague P. Interventions for helping patients to follow prescriptions for medications. Cochrane Database Systematic Reviews. 2002(2):CD000011. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD000011.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank all custody assistants, civilian jailers, sworn deputies and police officers, and reserve peace officers, law enforcement personnel and professionals who participated.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization by K.M., R.O. and J.D; Methodology, K.M. and R.O..; data collection, J.D.; formal analysis, C.M.; data curation, K.M. and C.M.; writing—original draft preparation, C.M.; writing—review and editing, K.M., R. O, and J.D.; project administration, C.M. All authors have read and approved the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Informed written consent was obtained, ethics approval was provided by an International Review Board (IRB 15–074), and Bond University’s Human Research Ethics Committee (RO1927).

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Additional file 1.

Inter-group comparison of demographic related and descriptive results.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

MacKenzie-Shalders, K., Matthews, C., Dulla, J. et al. Law enforcement personnel are willing to change, but report influencing beliefs and barriers to optimised dietary intake. BMC Public Health 20, 1638 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-020-09716-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-020-09716-z