Abstract

Background

The aims of the present study were to assess changes in weight status between the first and last year of primary education among children with overweight/obesity in response to locally implemented school-based prevention programs, and to assess the influence of process indicators, expressed as child-staff ratios (CSRs), on these changes.

Methods

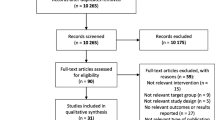

To meet the study objectives, a quasi-experimental design was used. Four municipalities that systematically monitored the weight status of schoolchildren and participated in the “Vivons en Forme” program agreed to provide the data available in their school medical service records. The local implementers involved in training sessions were mainly municipal staff in charge of serving midday school meals, which is compulsory in France, and those in charge of designing and facilitating creative, interactive activities at school between and after classes. CSRs were determined by occupation (school catering service/facilitator of extracurricular activities) and training session (healthy eating/physical activity) in each municipality program, and classified as low (1–5 children per adult) or moderate.

Results

During the 4 years of primary education, weight status improved in half of the children with overweight/obesity, and worsened in 6.6% of children with overweight/normal weight. In children who remained overweight, the BMI z-score diminished over time. Estimates of the positive 4-year weight changes were related to low CSRs in locally implemented variations of the program. Estimates increased with age and were significantly higher in low-to-moderate CSR multicomponent interventions than moderate CSR single-component intervention (reference). The moderate CSR multicomponent intervention had a similar effect as the reference. The estimated negative weight change decreased with age.

Conclusions

Our findings suggest that training ancillary school staff in experiential-focused interventions for healthy eating and physical activity in locally implemented school-based programs contributed positively to reducing childhood obesity during the four years of primary education without interfering with educational activities. The results also provide preliminary evidence that low CSRs could be pivotal for optimal outcomes, especially in deprived areas.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

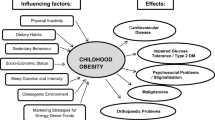

The rates of obesity and overweight are still increasing worldwide [1], and remain unchanged in France, affecting nearly 1 in 5 children, with the highest prevalence in deprived populations [2]. Obesity in childhood is difficult to reverse [3] and often persists into adulthood, causing many health problems [4]. According to systematic reviews, school-based prevention programs may be effective in promoting healthy behaviors [5,6,7]. These programs typically include educational, environmental, and social activities designed to improve dietary habits and reduce sedentary time in schoolchildren [8, 9]. However, even sound, evidenced–based interventions yield modest effects on adiposity measures [10, 11].

Insights from implementation science may partly explain these mitigated outcomes. How authorities bring prevention programs into the school communities may dramatically influence local dynamics. In France, the Education, Health, and Territory (EST) program included the core principles of health-promoting schools, such as staff training and support to develop school health policies focusing on the school environment and adaptation to a local context, community involvement, and the development of health-related knowledge, skills, and competencies [12], but decisions and approvals came from higher authorities, and this “top-down” approach created a reluctance to participate locally [13]. In addition, health education programs require teachers to acquire additional competencies [14] and to include health education in their curriculum [15]. However, teachers’ work is already described as increasing in complexity and intensity because of societal changes, reformed and increased work tasks, and multitasking [16]. Urgent unforeseen priorities, competing responsibilities, and high workload may also constitute barriers to successful implementation [17], especially when training and activities seem complex or theoretical [13].

The success of school-based prevention initiatives involves balancing evidence-based interventions with the flexibility to permit local educational communities to target their specific needs [18]. Fostering commitment entails giving local implementers the freedom to select the intervention components that best meet their needs and providing training to persons interacting with children [19], including teachers and ancillary staff in charge of non-teaching duties at school [13], such as catering and extracurricular activities. Following these core principles, some associations provide organizational backbone support [20] to local communities in charge of the education and care of children. This alternative approach to downstream interventions may induce variation between locally implemented programs, warranting a thorough examination of the relationship between process and outcome indicators through a quasi-experimental study design [21].

The aims of the present study were to assess changes in weight status among schoolchildren between the first and last year of primary education in response to locally implemented school-based prevention programs, and to assess the influence of process indicators, expressed as child-staff ratios (CSRs) by occupation/component, on these changes.

Methods

Intervention

The Vivons en Forme (VIF; “live healthy”) organization is a community-based prevention program aimed at promoting healthier lifestyles among children and their families, and involves municipal service in charge of child education and care under the supervision of a local coordinator. VIF is a continuation of the obesity prevention scheme previously known as Epode [22] in which local actors distributed toolkits fostering educational messages. However, providing information is modestly effective in changing behavior [23], and the non-governmental organization acting as a backbone structure changed its process in 2010, following four new pathways in order to improve program efficiency. First, the name of the program was changed for greater acceptance by the local stakeholders, including families and children, removing the mention of obesity in the name of the interventions. Second, a full social marketing approach was included for each yearly implemented theme [24]. Third, toolkit materials were pilot-tested in living labs to collect input from users and stakeholders before application in real-life settings and the participating cities [25]. Lastly, the implementation process was centered around local stakeholders, including school staff, as well as participation and empowerment [26]. The principle aim was to foster self-efficacy and a long-lasting effect in local school staff newly involved in the field of prevention and health promotion. Local coordinators have the freedom to select the components on which they want to focus their interventions and can request additional interventions during the course of the program. The basic underlying principle of this “choose-and-pick” approach was to foster staff involvement and sustainably change their interactions with children and parents. Each participating municipality applies for a minimal 5-year period, and their representatives have to regularly attend regional coordination meetings to receive up-to-date information on training sessions and tool upgrades.

Study design and participant selection

A quasi-experimental design was used was to meet the study objectives (Fig. 1). Four municipalities that systematically monitored the children’s weight status in the primary schools and were participating in the VIF program agreed to provide the data available in their school health records. In these municipalities, VIF counselors (a nutritionist, a sociologist, and the leading coordinator of the program) organized training sessions for the municipal staff in charge of school catering and extracurricular activities (ECAs) in primary schools. Training sessions and toolkits integrated roadmaps for conducting interactive activities with the children and to reinforce child-staff interactions via concrete experiences (Table 1). Brochures highlighting the beneficial effect of healthy eating (HE) and physical activity (PA) for children were systematically provided to parents [26]. They included tips on how to help kids stay hydrated by drinking water, on breakfast preparation, food breaks (including fruit), avoiding snacking between meals, on treats and smart portion sizes, and how to easily cook healthy meals at low cost.

Measures

Weight status

School nurses received training and standardized weighing scales to measure body mass index (BMI) in children using a BMI chart established by the International Obesity Task Force, which allows classification of children into weight categories [27] (i.e., underweight, normal weight, overweight, and obesity). They assessed the weight status of children during the first year of primary education at the school premises several weeks before the launch of each program in 2011. Children wore light clothing and no shoes during the weighing sessions. In addition, BMI Z-scores were determined using BMI-for-age reference standards [28] in order to account for the severity of overweight/obesity. A second weight assessment was performed among the same children during the last year of their primary education in 2015.

Socio-demographics

Weight status was matched for sex and age at inclusion, and whether children were schooled in a zone of priority education (zone d’education prioritaire, ZEP) was indicated. ZEP refers to schools in deprived, usually urban, settings that are earmarked for special state support. The decision to categorize a school as a ZEP was left to the administrative authorities, who can release additional funding to finance special needs education. Households and individuals of lower socio-economic status (unemployed, single mothers) are overrepresented in ZEPs compared to other city areas.

Process indicators

The number and occupation (school catering or ECAs) of persons who attended training sessions between 2011 and 2015 were systematically recorded by thematic component (i.e., HE and/or PA).

Data blinding and confidentiality

Each municipality provided data collected in the schools under their supervision without identifying a particular school or area. A study number was attributed to each municipality (City #) and each child in the database to ensure confidentiality. The final database was completed in 2016, but anonymized data were transmitted to researchers in charge of statistical analyses in 2018 due to the administrative authorization procedure in each participating city.

Statistical analysis

Process indicators were expressed as number and occupation of school ancillary staff attending training sessions by thematic component in each municipality, and then converted into CSRs, the number of children to each trained staff member, for each occupation and thematic session. Because an average ratio of 8 children per adult was found in early childhood education and care settings [29]. The CSR was classified as “low” if between 1 and 5 children per adult, and “moderate” otherwise.

Categorical data were expressed as numbers and percentages and compared using the chi-squared test, or the McNemar test. Numerical data were expressed as means and standard deviations (SDs) and compared by one-way analysis of variance or the non-parametric Wilcoxon comparison test. Outcome indicators were 4-year changes in weight status, which were considered “positive” if obesity changed to overweight/normal weight or if overweight changed to normal weight, and “negative” if normal weight changed to overweight/obesity or if overweight changed to obesity. To investigate the influence of process indicators on weight changes, we entered each CSR (low, moderate) as a covariate in a logistic regression using positive 4-year weight change as the binary outcome (yes/no), with and without adjustments for age at inclusion, gender, and school area (deprived/non-deprived). To investigate the effect of combined CSRs, the four variations of the VIF program locally implemented in the participating municipalities were entered in a regression model as a categorical covariate, as collinearity precluded the use of multiple regression with interaction terms. The same statistical procedure was carried out with negative 4-year weight change as a binary outcome in children characterized as overweight/normal weight at inclusion. Estimates were expressed as odds ratios (ORs) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs). Statistical analyses were performed using the SPSS statistical package, version 20 (SPSS, Chicago, Illinois, United States).

Results

Of the 900 first-grade children schooled in the four participating municipalities, 23 (2.7%) were not enrolled based on parental request, whereas 50 (5.6%) were lost to follow-up and excluded from further analyses. Comparisons revealed that those schooled in deprived areas were less frequently lost to follow-up (3.9%) than others (8.9%; p = 0.007). The 827 children included in the analyses (Table 2) were gender-balanced, with an average age of 6.4 years (SD 0.79), and 59.3% were schooled in deprived areas during the first year of primary education. The mean age was significantly higher in City 1 than the other municipalities (p < 0.001), whereas children schooled in deprived areas were significantly overrepresented in City 4 (77.4%) and City 1 (71.6%) compared to City 3 (45.3%) and City 2 (0%; p < 0.001). The distributions of gender and weight status were similar between municipalities.

At inclusion, 137 children met the criteria for overweight (16.6%) and 32 for obesity (3.9%; Table 3). Four years later, 101 children met the criteria for overweight (12.2%) and 31 for obesity (3.7%; p = 0.002). In children who remained overweight (n = 58), the BMI z-score decreased from 2.24 (0.48) to 2.04 (0.69; p = 0.014), but it remained unchanged in children with obesity [4.51 (1.82) vs. 4.09 (1.49)]. Weight status improved in half of the children with overweight/obesity (48.2 and 59.4%, respectively), with lower estimates in City 1 (38%) and City 2 (45.5%) and higher estimates in City 3 (68.4%) and City 4 (55.1%). Concomitantly, weight status worsened in 6.6% of children with overweight/normal weight.

The local implementers involved in training sessions were mainly municipal staff in charge of serving midday school meals, which is compulsory in France, and those in charge of designing and facilitating creative, interactive activities at school between and after classes. Over the 4-year study period, City 1 requested two training sessions on HE for the school catering staff, whereas City 2, City 3, and City 4 requested 3, 5, and 15 training sessions, respectively, on HE and PA for staff in charge of the school catering and staff in charge of ECAs. Finally, each participating municipality implemented a specific variation of the VIF program over the 4-year period (Table 4).

In the univariate analysis (Table 5), estimated positive 4-year weight changes increased significantly with low CSRs compared to moderate CSRs, even after adjusting for sex, age, and deprived school area. When the four variations of the VIF program were entered as categorical covariates in the regression model (Table 6), the estimated positive 4-year weight change was significantly higher in low-to-moderate CSR multicomponent interventions than the reference (moderate CSR single-component intervention), and increased with age after adjustment. The moderate CSR multicomponent intervention had a similar effect as the reference program. In children with overweight/normal weight at inclusion (N = 795), the estimated 4-year negative weight change decreased with age and was unrelated to the process indicators being studied.

Discussion

Between the first and the last year of primary education, weight status improved in half of the schoolchildren characterized as overweight/obesity at inclusion. In children who remained overweight, the BMI z-score diminished significantly over time, and being schooled in a deprived area had a negative, but not significant, influence.

The implementation mode under study was similar to traditional school-based prevention programs in that it provided training and materials to local stakeholders [12]. However, the VIF program provides tools previously tested in real-life settings and addresses thematic content over a long period of time based on a comprehensive social marketing methodology [30]. In addition, the interventions avoided interference with teachers’ curricula, enriching the existing school environments/interactions rather than implementing unusual and potentially disruptive procedures [13], and promoting experiential learning instead of lectures [19]. On the other hand, upstream discussions revealed that teachers had no particular interest in adding HE/PA to their curriculum, despite the recommendations of health experts [31]. Imposing their participation may have jeopardized local dynamics [13].

Yet, the data analyses elicited interesting insights. First, weight trajectories were reversed in half of children with overweight/obesity over 4 years, compared to approximately 38% over a 9-year period at the national level [2, 32]. Negative weight changes were marginal, and overweight severity diminished over time. This is important because 16.6% of children were considered overweight and 3.9% obese in the participating municipalities, compared to 10.1 and 2.4% of French children aged 6–10 years [2]. The higher than national average estimates could be due to the high level of social deprivation in these locations [33, 34], except for City 2, where others factors could be at play [35]. Second, positive changes in weight status were steadily related to lower CSRs, even after adjusting for sex, age, and deprived school area. Multi-component programs are widely acknowledged to be more successful than single-component interventions [36]. However, moderate CSRs weakened this benefit of the intervention in City 2, and the presence of low CSRs characterized the most effective variations in the VIF program. Many studies have investigated the relationship between CSRs and outcomes in childhood education and care, mostly on the cognitive and emotional development of the child, but the first attempt to systematically review and meta-analyze this highly complex and heterogeneous literature revealed few, if any, relationships [21]. These process indicators are often overlooked in obesity prevention program evaluations [10], and the reasons for variation at the local level warrant further examination. However, CSRs seem pivotal in childhood obesity prevention programs, though their optimal values still remain to be determined. Finally, it seems that older age had a positive influence on 4-year weight changes, though the children were relatively close to one another in regards to age (mean 6.38 years, SD 0.76). Minor differences in this life period could mark the transition between two milestones of cognitive development, but the complexity of developmental theories warrants caution [37]. If confirmed elsewhere, this result would advocate, at the very least, for including 2nd grade children in these programs.

The present study has limitations related, in part, to the implementation mode under examination. The avoidance of prescriptive approaches may have contributed to fostering local dynamics, but also precluded comparisons between balanced interventions. The lack of a control group constitutes a major limitation, as many factors besides the intervention could have influenced findings during the 4-year period. However, quasi experimental designs are frequently used to examine the effects of social programs [38], and assessing the intervention effect between the first and last year of primary education is consistent with monitoring school-based prevention programs. Furthermore, interactions between parents, children, and municipal school staff in charge of PA and HE were targeted by the programs but not directly assessed in the study. In addition, the municipalities participating in the study may have differed from other cities in France, as they systemically monitor the weight status of schoolchildren under their supervision. Considering the present findings, low CSRs in childhood prevention programs could be even more important in deprived areas [39]. This proportionate universalism [40] warrants further examination in relation to parental involvement and other variables of interest [35]. Nevertheless, a strength of this prospective study is that it relied on comparisons of reliable estimates of weight status collected twice at a 4-year interval among the same children at primary schools from distant municipalities, which avoided contamination.

Conclusions

Our findings suggest that training ancillary school staff in experiential-focused interventions in locally implemented school programs contributed positively to reducing childhood obesity during the four years of primary education without interfering in educational activities. They also provide preliminary evidence that low CSRs could be pivotal for optimal outcomes, especially in deprived areas, which warrants further investigation using a controlled study design.

Availability of data and materials

The dataset generated and analyzed during the current study is available in the Open Science Frame Network repository at https://osf.io/bfd8r

Abbreviations

- VIF:

-

Vivons en Forme (French: Live Healthy)

- HE:

-

Healthy Eating

- PA:

-

Physical activity

- BMI:

-

Body Mass Index

- ECA:

-

Extracurricular Activity

- CSR:

-

Chid-Staff Ratio

- ZEP:

-

(Zone d’éducation prioritaire: deprived area)

References

Fallah-Fini S, Rahmandad H, Huang TT, Bures RM, Glass TA. Modeling US adult obesity trends: a system dynamics model for estimating energy imbalance gap. Am J Public Health. 2014;104(7):1230–9.

Verdot C, Torres M, Salanave B, Deschamps V. Children and adults body mass index in France in 2015. Results of the Esteban study and trends since 2006. Bull Epidémiol Hebd. 2017;13:234–41.

Kamath CC, Vickers KS, Ehrlich A, McGovern L, Johnson J, Singhal V, et al. Clinical review: behavioral interventions to prevent childhood obesity: a systematic review and metaanalyses of randomized trials. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2008;93(12):4606–15.

Antony B, Jones G, Venn A, Cicuttini F, March L, Blizzard L, et al. Association between childhood overweight measures and adulthood knee pain, stiffness and dysfunction: a 25-year cohort study. Ann Rheum Dis. 2015;74(4):711–7.

Verrotti A, Penta L, Zenzeri L, Agostinelli S, De Feo P. Childhood obesity: prevention and strategies of intervention. A systematic review of school-based interventions in primary schools. J Endocrinol Investig. 2014;37(12):1155–64.

Knai C, Pomerleau J, Lock K, McKee M. Getting children to eat more fruit and vegetables: a systematic review. Prev Med. 2006;42(2):85–95.

Brown T, Moore TH, Hooper L, Gao Y, Zayegh A, Ijaz S, et al. Interventions for preventing obesity in children. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2019;7:CD001871.

Verjans-Janssen SRB, van de Kolk I, Van Kann DHH, Kremers SPJ, Gerards S. Effectiveness of school-based physical activity and nutrition interventions with direct parental involvement on children's BMI and energy balance-related behaviors - a systematic review. PLoS One. 2018;13(9):e0204560.

Kastorini CM, Lykou A, Yannakoulia M, Petralias A, Riza E, Linos A, et al. The influence of a school-based intervention programme regarding adherence to a healthy diet in children and adolescents from disadvantaged areas in Greece: the DIATROFI study. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2016;70(7):671–7.

Adab P, Pallan MJ, Lancashire ER, Hemming K, Frew E, Barrett T, et al. Effectiveness of a childhood obesity prevention programme delivered through schools, targeting 6 and 7 year olds: cluster randomised controlled trial (WAVES study). BMJ. 2018;360:k211.

French SA, Sherwood NE, Veblen-Mortenson S, Crain AL, JaKa MM, Mitchell NR, et al. Multicomponent obesity prevention intervention in low-income preschoolers: primary and subgroup analyses of the NET-works randomized clinical trial, 2012-2017. Am J Public Health. 2018;108(12):1695–706.

Jourdan D. A health education program based on training and support of stakeholders in the field. Sante Publique. 2013;25(4):421–31.

Darlington EJ, Violon N, Jourdan D. Implementation of health promotion programmes in schools: an approach to understand the influence of contextual factors on the process? BMC Public Health. 2018;18(1):163.

Jourdan D, Samdal O, Diagne F, Carvalho GS. The future of health promotion in schools goes through the strengthening of teacher training at a global level. Promot Educ. 2008;15(3):36–8.

Peralta LR, Dudley DA, Cotton WG. Teaching healthy eating to elementary school students: a scoping review of nutrition education resources. J Sch Health. 2016;86(5):334–45.

Brante G. Multitasking and synchronous work: Complexities in teacher work; 2009. p. 430–6.

van Nassau F, Singh AS, Broekhuizen D, van Mechelen W, Brug J, Chinapaw MJ. Barriers and facilitators to the nationwide dissemination of the Dutch school-based obesity prevention programme DOiT. Eur J Pub Health. 2016;26(4):611–6.

Ozer EJ, Wanis MG, Bazell N. Diffusion of school-based prevention programs in two urban districts: adaptations, rationales, and suggestions for change. Prev Sci. 2010;11(1):42–55.

Dudley DA, Cotton WG, Peralta LR. Teaching approaches and strategies that promote healthy eating in primary school children: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2015;12:28.

DuBow W, Hug S, Serafini B, Litzler E. Expanding our understanding of backbone organizations in collective impact initiatives. Community Dev. 2018;49(3):256–73.

Perlman M, Fletcher B, Falenchuk O, Brunsek A, McMullen E, Shah PS. Child-staff ratios in early childhood education and care settings and child outcomes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2017;12(1):e0170256.

Borys JM, Le Bodo Y, Jebb SA, Seidell JC, Summerbell C, Richard D, et al. EPODE approach for childhood obesity prevention: methods, progress and international development. Obes Rev. 2012;13(4):299–315.

WHOEurope, editor. Behaviour change strategies and health: the role of health systems. Regional Committee for Europe (Fifty-eighth session). Tbilisi, Georgia: WHO; 2008.

Raffin S. Le marketing social peut-il améliorer l’efficacité des programmes prévention ? Cahiers de Nutrition et de Diététique. 2013;48:184–90.

Evans J, Karvonen A. Living Laboratories for Sustainability: exploring the politics and epistemology of urban transition. In: Bulkeley H, Broto VC, Hodson M, Marvin S, editors. Cities and low carbon transition. Abingdon: Routledge; 2011.

Gurviez P, Raffin S. Social Marketing Campaigns for Healthier Eating Habits in France: VIF and “LES BONNES PORTIONS” (The Right Portions) Campaign Against Childhood Obesity. In: BasilGonzalo Diaz-Meneses ZD, Basil MD, editors. Social Marketing in Action: Cases around the world. Cham: Springer; 2019.

Cole TJ, Bellizzi MC, Flegal KM, Dietz WH. Establishing a standard definition for child overweight and obesity worldwide: international survey. BMJ. 2000;320(7244):1240–3.

de Onis M, Lobstein T. Defining obesity risk status in the general childhood population: which cut-offs should we use? Int J Pediatr Obes. 2010;5(6):458–60.

Department of Health. Minimum standards for childminding and day care for children under age 12. Belfast: Northern Ireland government;2012. http://childcarepartnerships.hscni.net/for-childcare-providers/minimum-standards-childminding-day-care (retrieved June 11th 2020).

Gurviez P, Raffin S. Social marketing campaigns for healthier eating habits in France. In: Basil D, Diaz-Meneses G, editors. Social marketing cases around the world. Cham: Springer International Publishing; 2019.

CDC. School-Based Obesity Prevention Strategies for State Policymakers. Washigton, DC: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2010.

Salanave B, Péneau S, Rolland-Cachera MF, Hercberg S, Castetbon K. Prévalences du surpoids et de l’obésité et déterminants de la sédentarité, chez les enfants de 7 à 9 ans en France en 2007. Saint-Maurice: Institut de veille sanitaire; 2011.

Kinra S, Nelder RP, Lewendon GJ. Deprivation and childhood obesity: a cross sectional study of 20,973 children in Plymouth, United Kingdom. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2000;54(6):456–60.

Conrad D, Capewell S. Associations between deprivation and rates of childhood overweight and obesity in England, 2007-2010: an ecological study. BMJ Open. 2012;2(2):e000463.

Stein D, Weinberger-Litman SL, Latzer Y. Psychosocial perspectives and the issue of prevention in childhood obesity. Front Public Health. 2014;2:104.

Waters E, de Silva-Sanigorski A, Hall BJ, Brown T, Campbell KJ, Gao Y, et al. Interventions for preventing obesity in children. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2011;12:CD001871.

Smith L. Critical readings on Piaget. Smith L, editor. New York: Routledge; 1996.

Fairweather GW, Tornatzky LG. Experimental methods for social policy research: Pergamon press; 1977.

Shackleton N, Hale D, Viner RM. Trends and socioeconomic disparities in preadolescent's health in the UK: evidence from two birth cohorts 32 years apart. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2016;70(2):140–6.

Carey G, Crammond B, De Leeuw E. Towards health equity: a framework for the application of proportionate universalism. Int J Equity Health. 2015;14:81.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to express their deepest gratitude to the municipal authorities and staff for their participation in this study.

Trial registration

The intervention was carried out at authors ‘discretion and not registered in a WHO primary registry.

Funding

The study was funded by the non-govermental organization leading the VIF program FLVS (Fédérons Les Villes pour la Santé), gathering financial support from local authorities in addition to the contributions of private partners, including Nestlé Foundation, Ferrero France, BEL, and Roquette Foundation. The funding bodies had no input in the study design; data collection, analysis, and interpretation; writing of the report; or the decision to submit the report for publication.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

SR, AL, GB, and RC contributed to the conception and design of the tools, trained the local stakeholders, and collected process indicators during interventions. BG suggested the study design, and AC performed the statistical analysis and wrote the first draft of the manuscript. AC, BG, and SR interpreted the data and drafted the final manuscript. All authors read and approved the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The study protocol was approved by the CNIL (Commission Nationale Informatique et Libertés), a governmental body in charge of checking compliance with ethical and individual data protection regulations in France. The CNIL fulfills the role of the Institutional Review Board (IRB) in France for non-invasive research. Children’s weight status and other variables were available from school medical service records and analysed after anonymization without Institutional Review Board oversight, as legally permitted in France (Article L. 541–1 du code de l’éducation) and in the United States (https://www.hhs.gov/ohrp/regulations-and-policy/decision-charts/index.html). The study’s protocol was approved by local authorities in charge of children’s education and care (municipal authorities, school directors, and school health services). Verbal consent was obtained from the parents prior to commencing the program. They received written information on the study objectives, about their right to accept or refuse research participation, and how to withdraw the child from the study once it started if they wished to do so. Since working with IRB was not required for routine school nurses practices in France, this procedure lacks an IRB examination. School nurses asked for the child’s permission before assessing weight status.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

Agnes Lommez (AL), Gaëlle Boulic (GB), and Raphaëlle Chaillou (RC) work at the VIF association. Sandrine Raffin (SR) is working for the VIF coordinating team.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Constant, A., Boulic, G., Lommez, A. et al. Locally implemented prevention programs may reverse weight trajectories in half of children with overweight/obesity amid low child-staff ratios: results from a quasi-experimental study in France. BMC Public Health 20, 941 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-020-09080-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-020-09080-y