Abstract

Background

The United States has the highest incarceration rate in the world. Incarceration can increase HIV risk behaviors for individuals involved with the criminal justice system and may be a driver of HIV acquisition within the community.

Methods

We used an agent-based model to simulate HIV transmission in a sexual-contact network representing heterosexual African American men and women in Philadelphia to identify factors influencing the impact of male mass incarceration on HIV acquisition in women. The model was calibrated using surveillance data and assumed incarceration increased the number of sexual contacts and decreased HIV care engagement for men post-release. Incarceration of a partner increased the number of sexual contacts for women. We compared a counterfactual scenario with no incarceration to scenarios varying key parameters to determine what factors drove HIV acquisition in women.

Results

Setting the duration of male high-risk sexual behavior to two years post-release increased the number of HIV transmissions to women by more than 20%. Decreasing post-release HIV care engagement and increasing HIV acquisition risk attributable to sexually transmitted infections (STIs) also increased the number of HIV transmissions to women. Changing the duration of risk behavior for women, the proportion of women engaging in higher risk behavior, and the relative risk of incarceration for HIV-infected men had minimal impact.

Conclusion

The mass incarceration of African American men can increase HIV acquisition in African American women on a population-level through factors including post-release high-risk behaviors, disruption of HIV care engagement among formerly incarcerated men, and increased STI prevalence. These findings suggest that the most influential points of intervention may be programs seeking to reduce male risk behaviors and promote HIV care engagement post-release, as well as STI testing and treatment programs for recently incarcerated men, as well as women with incarcerated partners.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

The United States is home to less than 5 % of the world’s population yet imprisons over a fifth of the world’s prisoners [1]. As of 2015, over 2.2 million Americans were held in penal institutions, either awaiting trial or serving a sentence [1]. As a result, incarceration has become a “normal life event” for many men and women in the US, particularly within communities of color. The “war on drugs”, racial biases in arrests and sentencing, and other structural factors have led to marked racial disparities in incarceration [2,3,4]. By the age of 34, an African American male with less than a high school education has a 69% probability of having spent time in prison or jail [5].

The mass incarceration of African American men is hypothesized to play an important role in racial HIV disparities [6,7,8,9,10]. Heterosexual African Americans with a history of incarceration are six times more likely to be HIV-infected compared to those with no incarceration history, and numerous observational studies suggest a history of incarceration is a strong and consistent risk factor for high-risk sexual behaviors post-release [6, 11,12,13,14,15,16,17]. A study in Baltimore found that 28% of men with a recent incarceration event had five or more sexual contacts in the past year and 32% reported partner concurrency (defined as partnerships that overlap in time) [6]. Additionally, incarceration can disrupt HIV care engagement. Recently incarcerated HIV-infected men are more likely to disengage from HIV care and experience viral rebound post-release, which in turn increases HIV-related morbidity and the likelihood of HIV transmission to their sexual and drug-using partners [18,19,20,21,22,23,24]. Consequently, the mass incarceration of men may be a major driver of HIV acquisition for women.

Mass incarceration disproportionately affects African American men in urban, low-income communities whose partners are often already at high risk for sexual HIV transmission. Up to 80% of inmates are married or in committed relationships at the time of incarceration [14, 25]. It is estimated that over half of these relationships end during incarceration; thus, incarceration results in the dissolution of sexual partnerships and the disruption of social networks, which can result in negative behavioral outcomes that increase HIV risk [10, 26]. Previous studies have reported an increased risk of sexually transmitted infections (STIs), a greater likelihood of having five or more partners in the past year, and an increased prevalence of partner concurrency among women with a recently incarcerated male partner [6, 27]. However, it is not known what factors related to the mass incarceration of African American men affect HIV transmission and prevalence among women at the population level. The current analysis used an agent-based model (ABM) to determine what factors modify the impact of the mass incarceration of African American men on HIV acquisition in African American women, using the city of Philadelphia as a case study. Philadelphia was selected as the setting for the model as the city has the highest per capita incarceration rate of the 10 largest U.S. cities, with 2% of African American men behind bars [28].

ABMs have several distinct advantages compared to other methods for this research question [29, 30]. Agent-based modelling is of particular utility when interference (i.e., the outcome of one individual influences the exposure status of others) dominates the behavior of the system, and thus influences exposure-disease relationships [31]. ABMs allow us to model changes in risk behavior (e.g., an increase in sexual partners) that often occur after the incarceration of an individual in that agent’s sexual network. Additionally, ABMs can be used to examine the effect of multiple exposures that interact in dynamic ways to affect population-level health outcomes [31]. ABMs have been used to estimate the effect of intervention strategies in preventing HIV transmission within networks of people who inject drugs, understand the contribution of acute HIV infection to community HIV incidence, and detail HIV transmission dynamics [32,33,34,35,36]. Through explicitly simulating both the individual behavioral and network-level effects of incarceration, use of an ABM allows us to address questions of HIV acquisition attributable to mass incarceration.

Methods

We used the Treatment of Infection and Transmission in Agent-Based Networks (TITAN) model, a dynamic model of HIV transmission. The TITAN model is an ideal platform for this analysis as the model has successfully been used to explore how racial inequities in pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) programs, treatment as prevention efforts among people who inject drugs, and other complex processes impact HIV transmission within a mature epidemic setting [37,38,39]. The TITAN model is parameterized from peer-reviewed literature, surveillance data, and other sources and then calibrated to reflect the real-world trends in HIV transmission. This analysis simulated the movement of men in and out of prison or jail to understand the interaction between incarceration and HIV acquisition in African American women. The TITAN model was run with discrete monthly time-steps and an open population. At each time step, sexual relationships or “links” between agents are formed, retained, or broken, thus representing the evolution of a population-based sexual HIV transmission network. Full details for this model, including model parameterization and technical specifications, are provided in the supplemental material.

Model population

The agent-based model used for this analysis generated a virtual population representing the total population of heterosexual African American men and women (n = 440,000) living in Philadelphia from 2005 to 2015. Although the model initializes the network in 2005, the first three years of model simulation (i.e., the burn-in period) are not included in the main results, as this period was necessary in order to reach a steady-state and accurately reflect historical trends in empirical data for the status quo model.

Each individual agent had both fixed (e.g., gender) and dynamic (e.g., HIV infection status, incarceration status) characteristics. HIV-infected agents had attributes (e.g., HIV diagnosis status) that varied over time according to care engagement. Sexual networks were assumed to be exclusively heterosexual and relationships were defined as either main (≥1 month in duration) or casual (≤1 month in duration). Agents had differing probabilities of mortality depending on gender, HIV infection status, and HIV disease stage. An overview of model parameter and processes is presented in Table 1. Parameters and data sources used to define agent characteristics are fully described in Additional file 1: Tables S1-S7 within the supplement.

HIV prevalence, screening and treatment

Data from the AIDS Activities Coordinating Office (AACO), the HIV surveillance unit in the Philadelphia Department of Public Health, were used to parameterize and calibrate trends in HIV prevalence and incidence. At model initialization (representing the year 2005), the HIV prevalence was 1.58% for African American men and 1.18% for African American women. Following historical trends, the number of HIV-infected individuals on highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART) and achieving viral suppression increased over time. Selected parameters were held constant throughout model simulations, including the proportion of HIV-infected individuals who were diagnosed (75%), the annual probability of HAART discontinuation within the general community (42% for men and 52% for women), and the monthly probability of HIV testing for the community (3.4% for men and 3.9% for women) based on published data (see Additional file 1: Table S3 within the supplement).

Incarceration

In November 2005, 2.7–2.8% of Philadelphia’s male African American population over the age of 18 was currently incarcerated [28]. In our model, incarceration was defined as being held in a prison or any other kind of detention facility for at least one month or longer. At model initialization, 2.74% of the male agents were incarcerated. Detailed information using 2006 data from the Philadelphia Commission on Sentencing on sentence lengths and incarceration rates for African American men in Philadelphia were used to parameterize the model [40]. Rates of incarceration and sentence lengths were reported by type of correctional facility (jail vs. prison) and recidivism status (first-time offender vs. prior incarceration). For example, the annual rate of incarceration in prison for African American men with a prior record was 251 per 100,000 with an average minimum sentence of 45.6 months. These rates and sentence lengths were held constant through model runs.

Based on previously published research on HIV testing within Philadelphia correctional facilities, we assumed that 69% of agents were tested for HIV at intake [41]. Consistent with available data, 40% of diagnosed HIV-infected men were assumed to achieve viral suppression during incarceration [23]. Individuals experiencing incarceration have multiple barriers to achieving viral suppression while incarcerated including the lack of universal HIV testing at intake, limited infrastructure or staffing (e.g., infectious disease physician), as well as challenges with HAART adherence [23, 41]. Since we were interested in examining the effect of male incarceration on women’s HIV acquisition, only male agents were eligible to experience incarceration.

Within the model, risk behaviors were parameterized using observational studies on the impact of incarceration and partner incarceration [14, 15, 23, 42, 43]. During incarceration, the agent ceases all sexual contact; however, relationships can be maintained so that a proportion of relationships last through incarceration and sexual activity resumes post-release. The model assumed that the probability of relationship dissolution was higher if the male agent entered jail or prison, resulting in increased relationship turnover among those incarcerated and their partners [26].

Women were eligible to experience increased risk behavior only if the incarcerated partner was a main partner. Women had a higher probability of entering the “high-risk group” if a relationship dissolved during incarceration. High-risk behavior for women consisted of a higher mean number of sexual partners and was initiated immediately upon the partner’s incarceration and continued throughout the partner’s incarceration or until six months following the relationship dissolution [42]. For the six months following release from either prison or jail, all men entered a period of high-risk behavior with an increased number of sexual partners from a median of 3 (interquartile range: 1,7) partners per year to an average of 1.8 partners per month [14].

Incarceration also impacted HIV care engagement. A recent systematic review of national data found that 51% of HIV diagnosed prisoners are on HAART while incarcerated, but only 29% are on HAART after release [23]. Therefore, within our model, only half of the HIV-infected men who were virally suppressed during incarceration maintained viral suppression by six months post-release [23]. In summary, incarceration or partner incarceration was modeled to directly increase the mean number of sexual partners, decrease the probability of maintaining viral suppression for male HIV-infected agents, and increase the probability of relationship dissolution. Increased rates of partner concurrency and relationship turnover emerged as a result of these changed behaviors rather than as a result of pre-programmed parameters. Figure 1 reviews the impact of male incarceration within the model.

Model scenarios

A status quo scenario was calibrated using surveillance data on HIV prevalence and incidence rates for the study period (2005–2015). Six scenarios varying key parameters hypothesized to influence the impact of mass incarceration were then performed. Specifically, we varied the duration of high-risk behavior for men post-release (3 months, 24 months), duration of high-risk behavior for women (3 months, 24 months), the proportion of women engaging in high-risk behavior (0, 100%), HAART coverage for HIV-infected men at six months post-release (0, 100%), the relative risk of incarceration for HIV-infected men compared to HIV-uninfected men (2, 5), and doubled the risk of HIV transmission per unprotected vaginal sex act to account for the increased probability of a current STI among high-risk agents (for high-risk period only, for the remainder of the model run). In order to isolate the effect of the selected parameter, we held values for the other key parameters constant at a referent value. Each scenario was run 100 times with ¼ the total population size (n = 110,000) using Markov Chain Monte Carlo simulations; results were then scaled to reflect the target population (n = 440,000).

For each scenario, we projected the HIV incidence and prevalence rates and total number of transmission events for African American women over the study period. Model scenarios were compared to a counterfactual scenario where no agent experienced incarceration by calculating the mean difference in the number of new HIV infections among African American women.

Results

The model was successfully calibrated to reflect HIV prevalence and incidence trends for African American men and women living in Philadelphia from 2005 to 2015. Over the study period, the average HIV prevalence was 2397 per 100,000 for men and 1857 per 100,000 for women, and the average annual HIV incidence was 75 per 100,000 for men and 64 per 100,000 for women. Over the entire study period, including the three-year run-in period, 9.6% (n = 17,117) of men and 8.3% (n = 380) of HIV-infected men experienced at least one episode of incarceration. On average, 8.1% (n = 21,096) of women experienced a period of high-risk behavior related to a partner’s incarceration. There were 1641 (1421-1881) transmission events among women over the 10-year period in the status quo scenario with referent values for key parameters. We then ran a counterfactual scenario with no incarceration (i.e., incarceration rate was set to 0). In the absence of incarceration, there were 1632 (95% SI: 1427-1861) HIV transmissions among women over ten years. The number and percent difference in cumulative HIV infections among women for scenarios varying key parameters compared to the scenario without incarceration are presented in Table 2.

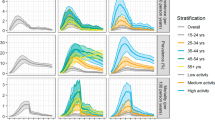

Increasing the duration of male high-risk behavior post-release had the greatest impact on HIV acquisition in women (see Fig. 2). If risk behavior lasted for 24 months, there were 449 additional HIV infections to women over the study period compared to the no incarceration scenario. Decreasing HAART coverage to 0% for men post-release (i.e., no men were virally suppressed by six months post-release), resulted in 135 additional infections. Doubling the HIV transmission risk per unprotected vaginal sex act for high-risk men and women to account for the increased probability of an STI increased the number of HIV transmissions. When the increased HIV transmission risk was limited to the high-risk period, there were 26 additional HIV infections. If high-risk agents were assumed to have an increased HIV transmission risk for the remainder of the study period, there were 184 additional HIV infections. Scenarios varying the duration of female risk behavior, the proportion of women engaging in high-risk behavior, and the relative risk of incarceration for HIV-infected men compared to uninfected men had a minimal impact on HIV transmissions.

HIV transmissions attributable to changing selected parameter from upper to lower bound valuea. aThe y-axis represents the number of HIV transmissions attributable to changing the selected parameter from lower to upper bound value. Calculated as the absolute difference in the mean number of HIV transmissions using values reported in Table 1. For the male duration of high risk behavior parameter this is equivalent to 449-(-25) =474

Discussion

Using Philadelphia as a case study, we found that the mass incarceration of African American men can substantially increase the number of HIV transmissions to African American women within the community. Factors including post-release high-risk behaviors, disruption of HIV care among formerly incarcerated men, and increased STI prevalence significantly modified the impact of incarceration on HIV acquisition in women. These factors have the potential to increase the number of HIV transmissions among women attributable to mass incarceration and may represent targets for intervention efforts.

To our knowledge, this is the first study to evaluate the impact of behavioral, network, and care engagement processes associated with mass male incarceration on HIV acquisition in women. The impact of incarceration varied depending on several factors. Assuming that high-risk behavior of men post-release lasted two years resulted in a greater than 20% increase in the number of HIV transmissions among women compared to the no incarceration scenario. Limited empirical data exists for parameterization of the duration (e.g., 6 vs. 24 months) of increased sexual risk behaviors for men after incarceration. The majority of existing studies have focused on recently released men, typically interviewing men within the first year post-release and finding increased sexual risk behaviors [13, 14, 43]. While our model assumed the duration of high-risk behavior was limited to no more than the first two years post-release, it is plausible that men with a history of incarceration become more likely to engage in HIV risk behaviors for years, or even for the rest of their lives [12]. Consequently, we may be underestimating the potential impact of mass incarceration. Longitudinal studies that follow men post-release for several years are needed in order to better understand the long-term impact of incarceration on sexual risk behavior.

Women with an incarcerated partner in the past year are over twice as likely to have a current STI compared to women without a recently incarcerated partner [6]. STI prevalence is also higher among men with a recent incarceration compared to those without a history of incarceration [6, 44, 45]. A current STI increases the likelihood of HIV acquisition: ranging from a two-fold increase with bacterial vaginosis to a seven-fold increase with gonorrhea [46]. The same processes through which incarceration contributes to HIV incidence (e.g., partner concurrency, increased partners) are also likely to have the same effect upon STI incidence rates. Therefore, we doubled the probability of HIV transmission per unprotected vaginal sex act for high-risk individuals (men and women) to account for this increased likelihood of a current STI. This led to significant differences in the number of HIV transmissions between the no incarceration and the other scenarios accounting for this increased HIV acquisition risk. These findings suggest that STIs are an important and modifiable factor related to the impact of incarceration on HIV acquisition.

Since the U.S. Supreme Court ruling in 1976 (Estelle v. Gamble) established the constitutional right to basic health care in correctional facilities, facilities have been mandated to provide prison health services for acute and chronic conditions [47]. However, a systematic review using national data estimated that only 40% of individuals living with HIV achieve viral suppression while incarcerated [23]. Opt-out HIV testing upon intake at a correctional facility has been shown to be both feasible and acceptable and represents the first step to ensuring increased HIV care engagement for individuals experiencing incarceration [48]. Providing support for HIV care including access to HIV providers, adherence counselors, and other services while individuals are incarcerated can improve care engagement during and after incarceration. In addition, there is a need for programs to reduce the risk of HIV transmission (e.g., condom distribution) during incarceration. Even in the presence of these barriers, numerous studies have found that HIV-infected men have improved HIV care engagement and viral suppression while incarcerated compared to engagement when in the community [4, 21, 22, 49, 50]. Substantial barriers to HIV care engagement post-release include both structural and socioeconomic factors [51]. Following release from a correctional facility, many individuals return to the community without HAART medication to take home or a follow-up appointment with an HIV care provider [18, 52]. Many men and women lack health insurance or are required to reapply for health insurance post-release [53]. These logistical barriers often lead to treatment interruptions. In addition, significant socioeconomic factors frequently challenge HIV care engagement. Lack of stable housing, poverty, and stigmatization related to both HIV and incarceration decrease the probability of sustained HIV care engagement [47, 52,53,54]. Mental health and substance use disorders are highly prevalent among HIV-infected prisoners and are associated with decreased ART adherence and increased HIV risk-taking behaviors [55]. Without treatment for mental health and substance use disorders, HIV-infected individuals are more likely to disengage from HIV care and virally rebound [51, 56]. Successfully linking and retaining individuals to HIV care post-release requires addressing the logistical and socioeconomic barriers to care before release as well as the comorbidities that complicate care engagement [51].

Future work with this model will focus on understanding the impact of the HIV care continuum during and after incarceration and PrEP prescription strategies for women impacted by a partner’s incarceration. Within our model, lack of HIV care engagement post-release increased HIV acquisition in women. Efforts to prevent HAART treatment interruptions through interventions such as transitional care coordination, substance use treatment and mental health services, and integrating health service delivery organizations may decrease HIV acquisition in women [22, 57]. Further research is needed to clarify which strategies would be most effective in improving HIV care engagement in order to improve the health of formerly incarcerated persons and prevent HIV transmission to their partners. In addition, there is a need to increase awareness regarding the risk of HIV acquisition associated with a partner’s incarceration for women. Several experts have called for the use of relationship or partner characteristics such as a partner’s concurrency, a partner’s incarceration, or intimate partner violence to help guide HIV prevention efforts [58]. A recent study evaluating an HIV risk index with five hundred African American women in Atlanta found that partner characteristics (including a history of incarceration) better predicted laboratory-confirmed sexually transmitted infection than other indicators, including recent condomless sex [59]. Therefore, we plan to use this model to explore the potential impact of PrEP prescription for women impacted by a partner’s incarceration on HIV transmission dynamics in a future study.

Our study is subject to several limitations. First, ABMs are not able to simulate the breadth of human experiences related to incarceration (e.g., poverty, stigma, drug relapse). Although we provide our virtual population with the ability to replicate a complex set of interactive events, ABMs will never fully capture the complexity of human behavior. In addition, race-specific or Philadelphia-specific data was not available for some parameters, including the duration of high-risk behavior. However, analyses were used to explore the potential impact that changing these parameters had on study findings. Additional HIV risk factors that were not fully captured within our model include assortative mixing (i.e., higher risk individuals are more likely to interact with other high-risk individuals), engagement in other HIV risk behaviors (e.g., injection drug use), or the increased HIV risk among men who have sex with men and women (MSMW) [10]. A modest percentage (approximately 6%) of black men who have sex with women report having a history of sex with men [60]. Therefore, the simulated incarceration effect is conservative to the extent that incarceration increases assortative mixing and the model does not include MSMW or account for other HIV risk behaviors [61].

In addition, we assumed that sexual contact ceased during incarceration despite evidence to the contrary [62]. However, studies have shown the majority of HIV transmission occurs outside of prison facilities and therefore, this assumption is unlikely to significantly impact our results and would have led to the underestimation of impact [63, 64]. Within the model, the probability of being incarcerated did not vary by age as rates are for the general adult population of African American men. Therefore, incarceration was relatively rare compared to what observational studies have shown for subsets of the population (i.e., African American men ages 18–35) [6]. Sexual partner selection was not based on age and therefore, we were not able to take into account the differential prevalence of partner incarceration by age. Therefore, the model underestimated the prevalence of incarceration and partner incarceration for a proportion of the population, and consequently, may have underestimated the impact of incarceration for this subset.

These limitations aside, this study has several strengths. First, with regards to the model calibration, we used validated, population-based surveillance data. Second, many of the model parameters (e.g., likelihood of HIV acquisition per unprotected vaginal sex encounter, mean number of sexual partners) and assumptions have already been tested in previous studies [32,33,34,35,36]. Finally, use of an ABM enabled us to estimate effects that are not possible to measure in a trial or observational study.

Conclusion

The mass incarceration of African American men can affect HIV acquisition in African American women on the population-level. The duration of male high-risk behavior, disrupted HIV care engagement of men post-release, and increased STI prevalence among those affected by incarceration or partner incarceration potentially drive the effect of mass incarceration on HIV acquisition in women. These findings reinforce the importance of programs seeking to reduce male HIV risk behaviors and promote HIV care engagement post-release as well as STI testing and treatment programs for recently incarcerated men and women with incarcerated partners. These efforts should complement work to reduce overall incarceration rates through criminal justice reform to reduce the number of individuals exposed to the deleterious consequences of incarceration.

Abbreviations

- AACO :

-

AIDS Activities Coordinating Office

- ABM :

-

Agent-based model

- HAART :

-

Highly active antiretroviral therapy

- HIV :

-

Human immunodeficiency virus

- MSMW :

-

men who have sex with men and women

- PrEP :

-

Pre-exposure prophylaxis

- STI :

-

Sexually transmitted infection

- TITAN :

-

Treatment of Infection and Transmission in Agent-Based Networks

References

World Prison Brief. World Prison Population List, eleventh edition. In: Walmsley R, editor. Institute for Criminal Policy Research; 2015.

Alexander M: The new Jim crow : mass incarceration in the age of colorblindness. New York Jackson, Tenn.: new press ; distributed by Perseus distribution; 2010.

The Sentencing Project: Report of The Sentencing Project to the United Nations Human Rights Committee Regarding Racial Disparities in the United States Criminal Justice System. In.; 2013.

Wildeman C, Wang EA. Mass incarceration, public health, and widening inequality in the USA. Lancet. 2017;389(10077):1464–74.

Kearney MS, Harris BH, Jácome E, Parker L. Ten economic facts about crime and incarceration in the United States. The Hamilton Project. 2014. http://www.hamiltonproject.org/assets/legacy/files/downloads_and_links/v8_THP_10CrimeFacts.pdf. Accessed 11 Dec 2018.

Rogers SM, Khan MR, Tan S, Turner CF, Miller WC, Erbelding E. Incarceration, high-risk sexual partnerships and sexually transmitted infections in an urban population. Sex Transm Infect. 2012;88(1):63–8.

Adimora AA, Schoenbach VJ. Social context, sexual networks, and racial disparities in rates of sexually transmitted infections. J Infect Dis. 2005;191(Suppl 1):S115–22.

Johnson R, xa C, Raphael S. The effects of male incarceration dynamics on acquired immune deficiency syndrome infection rates among African American women and men. J. Law Econ. 2009;52(2):251–93.

Widman L, Noar SM, Golin CE, Willoughby JF, Crosby R. Incarceration and unstable housing interact to predict sexual risk behaviours among African American STD clinic patients. Int J STD AIDS. 2014;25(5):348–54.

Friedman SR, Cooper HL, Osborne AH. Structural and social contexts of HIV risk among African Americans. Am J Public Health. 2009;99(6):1002–8.

Adimora AA, Schoenbach VJ, Doherty IA. HIV and African Americans in the southern United States: sexual networks and social context. Sex Transm Dis. 2006;33(7 Suppl):S39–45.

Khan MR, Miller WC, Schoenbach VJ, Weir SS, Kaufman JS, Wohl DA, Adimora AA. Timing and duration of incarceration and high-risk sexual partnerships among African Americans in North Carolina. Ann Epidemiol. 2008;18(5):403–10.

Epperson MW, El-Bassel N, Chang M, Gilbert L. Examining the temporal relationship between criminal justice involvement and sexual risk behaviors among drug-involved men. J Urban Health. 2010;87(2):324–36.

Morrow KM, Project SSG. HIV, STD, and hepatitis risk behaviors of young men before and after incarceration. AIDS Care. 2009;21(2):235–43.

Adimora AA, Schoenbach VJ, Martinson F, Donaldson KH, Stancil TR, Fullilove RE. Concurrent sexual partnerships among African Americans in the rural south. Ann Epidemiol. 2004;14(3):155–60.

Khan MR, Doherty IA, Schoenbach VJ, Taylor EM, Epperson MW, Adimora AA. Incarceration and high-risk sex partnerships among men in the United States. J Urban Health. 2009;86(4):584–601.

Epperson M, El-Bassel N, Gilbert L, Orellana ER, Chang M. Increased HIV risk associated with criminal justice involvement among men on methadone. AIDS Behav. 2008;12(1):51–7.

Stephenson BL, Wohl DA, Golin CE, Tien H-C, Stewart P, Kaplan AH. Effect of release from prison and re-incarceration on the viral loads of HIV-infected individuals. Public Health Rep. 2005;120(1):84.

Baillargeon J, Giordano TP, Rich JD, Wu ZH, Wells K, Pollock BH, Paar DP. Accessing antiretroviral therapy following release from prison. JAMA. 2009;301(8):848–57.

Springer SA, Pesanti E, Hodges J, Macura T, Doros G, Altice FL. Effectiveness of antiretroviral therapy among HIV-infected prisoners: reincarceration and the lack of sustained benefit after release to the community. Clin Infect Dis. 2004;38(12):1754–60.

Meyer JP, Cepeda J, Springer SA, Wu J, Trestman RL, Altice FL. HIV in people reincarcerated in Connecticut prisons and jails: an observational cohort study. Lancet HIV. 2014;1(2):e77–84.

Rich JD, Beckwith CG, Macmadu A, Marshall BD, Brinkley-Rubinstein L, Amon JJ, Milloy M, King MR, Sanchez J, Atwoli L. Clinical care of incarcerated people with HIV, viral hepatitis, or tuberculosis. Lancet. 2016;388(10049):1103–14.

Iroh PA, Mayo H, Nijhawan AE. The HIV care cascade before, during, and after incarceration: a systematic review and data synthesis. Am J Public Health. 2015;105(7):e5–e16.

Milloy MJ, Montaner JS, Wood E. Incarceration of people living with HIV/AIDS: implications for treatment-as-prevention. Curr HIV/AIDS Rep. 2014;11(3):308–16.

Grinstead OA, Faigeles B, Comfort M, Seal D, Nealey-Moore J, Belcher L, Morrow K. HIV, STD, and hepatitis risk to primary female partners of men being released from prison. Women & health. 2005;41(2):63–80.

Khan MR, Behrend L, Adimora AA, Weir SS, Tisdale C, Wohl DA. Dissolution of primary intimate relationships during incarceration and associations with post-release STI/HIV risk behavior in a southeastern city. Sex Transm Dis. 2011;38(1):43–7.

Khan MR, Wohl DA, Weir SS, Adimora AA, Moseley C, Norcott K, Duncan J, Kaufman JS, Miller WC. Incarceration and risky sexual partnerships in a southern US city. J Urban Health. 2008;85(1):100–13.

Goldkamp JS, Vîlcică E, Weiland D, Ke W. Confinement and the justice process in Philadelphia: its features and implications for planning. Crime and Justice Research Center, Department of Criminal Justice, Temple University. 2006. https://www.phila.gov/prisons/PDF/phillyConfinementFinal1.pdf. Accessed 11 Dec 2018.

Garnett GP, Cousens S, Hallett TB, Steketee R, Walker N. Mathematical models in the evaluation of health programmes. Lancet. 2011;378(9790):515–25.

Bonabeau E. Agent-based modeling: methods and techniques for simulating human systems. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99(Suppl 3):7280–7.

Marshall BD, Galea S. Formalizing the role of agent-based modeling in causal inference and epidemiology. Am J Epidemiol. 2015;181(2):92–9.

Marshall BD, Paczkowski MM, Seemann L, Tempalski B, Pouget ER, Galea S, Friedman SR. A complex systems approach to evaluate HIV prevention in metropolitan areas: preliminary implications for combination intervention strategies. PLoS One. 2012;7(9):e44833.

Monteiro JF, Galea S, Flanigan T, Monteiro Mde L, Friedman SR, Marshall BD. Evaluating HIV prevention strategies for populations in key affected groups: the example of Cabo Verde. Int J Public Health. 2015;60(4):457–66.

Monteiro JF, Escudero DJ, Weinreb C, Flanigan T, Galea S, Friedman SR, Marshall BD. Understanding the effects of different HIV transmission models in individual-based microsimulation of HIV epidemic dynamics in people who inject drugs. Epidemiol Infect. 2016;144(8):1683–700.

Escudero DJ, Lurie MN, Mayer KH, Weinreb C, King M, Galea S, Friedman SR, Marshall BD. Acute HIV infection transmission among people who inject drugs in a mature epidemic setting. AIDS. 2016;30(16):2537–44.

Marshall BD, Friedman SR, Monteiro JF, Paczkowski M, Tempalski B, Pouget ER, Lurie MN, Galea S. Prevention and treatment produced large decreases in HIV incidence in a model of people who inject drugs. Health Aff (Millwood). 2014;33(3):401–9.

Goedel WC, King MRF, Lurie MN, Nunn AS, Chan PA, Marshall BDL. Effect of racial inequities in pre-exposure prophylaxis use on racial disparities in HIV incidence among men who have sex with men: a modeling study. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2018;79(3):323–9.

Gantenberg JR, King M, Montgomery MC, Galarraga O, Prosperi M, Chan PA, Marshall BDL. Improving the impact of HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis implementation in small urban centers among men who have sex with men: an agent-based modelling study. PLoS One. 2018;13(7):e0199915.

Escudero DJ, Lurie MN, Mayer KH, King M, Galea S, Friedman SR, Marshall BDL. The risk of HIV transmission at each step of the HIV care continuum among people who inject drugs: a modeling study. BMC Public Health. 2017;17(1):614.

The State of Black Philadelphia. Urban League of Philadelphia; 2007. http://www.urbanleaguephila.org/wp-content/uploads/2013/01/ULP_SOBP.pdf. Accessed 11 Dec 2018.

Beckwith CG, Nunn A, Baucom S, Getachew A, Akinwumi A, Herdman B, DiBartolo P, Spencer S, Brown D, Lesansky H. Rapid HIV testing in large urban jails. Am J Public Health. 2012;102(S2):S184–6.

Cooper HL, Caruso B, Barham T, Embry V, Dauria E, Clark CD, Comfort ML. Partner incarceration and African-American women’s sexual relationships and risk: a longitudinal qualitative study. J Urban Health. 2015;92(3):527–47.

Seal D, Eldrige G, Kacanek D, Binson D, MacGowan R, Group PSS. A longitudinal, qualitative analysis of the context of substance use and sexual behavior among 18-to 29-year-old men after their release from prison. Soc Sci Med. 2007;65(11):2394–406.

Khan MR, Golin CE, Friedman SR, Scheidell JD, Adimora AA, Judon-Monk S, Hobbs MM, Dockery G, Griffin S, Oza KK, et al. STI/HIV sexual risk behavior and prevalent STI among incarcerated African American men in committed partnerships: the significance of poverty, mood disorders, and substance use. AIDS Behav. 2015;19(8):1478–90.

Khan MR, Epperson MW, Mateu-Gelabert P, Bolyard M, Sandoval M, Friedman SR. Incarceration, sex with an STI- or HIV-infected partner, and infection with an STI or HIV in Bushwick, Brooklyn, NY: a social network perspective. Am J Public Health. 2011;101(6):1110–7.

van de Wijgert JH, Morrison CS, Brown J, Kwok C, Van Der Pol B, Chipato T, Byamugisha JK, Padian N, Salata RA. Disentangling contributions of reproductive tract infections to HIV acquisition in African women. Sex Transm Dis. 2009;36(6):357–64.

Dumont DM, Brockmann B, Dickman S, Alexander N, Rich JD. Public health and the epidemic of incarceration. Annu Rev Public Health. 2012;33:325–39.

Rosen DL, Wohl DA, Golin CE, Rigdon J, May J, White BL, Leone PA, Hudgens MG, Bowling JM. Comparing HIV case detection in prison during opt-in vs. opt-out testing policies. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2016;71(3):e85–8.

Meyer JP, Cepeda J, Wu J, Trestman RL, Altice FL, Springer SA. Optimization of human immunodeficiency virus treatment during incarceration: viral suppression at the prison gate. JAMA Intern Med. 2014;174(5):721–9.

Schneider JA, Kozloski M, Michaels S, Skaathun B, Voisin D, Lancki N, Morgan E, Khanna A, Green K, Coombs RW, et al. Criminal justice involvement history is associated with better HIV care continuum metrics among a population-based sample of young black MSM. AIDS. 2017;31(1):159–65.

Springer SA, Spaulding AC, Meyer JP, Altice FL. Public health implications for adequate transitional care for HIV-infected prisoners: five essential components. Clin Infect Dis. 2011;53(5):469–79.

Frank JW, Wang EA, Nunez-Smith M, Lee H, Comfort M. Discrimination based on criminal record and healthcare utilization among men recently released from prison: a descriptive study. Health Justice. 2014;2:6.

Haley DF, Golin CE, Farel CE, Wohl DA, Scheyett AM, Garrett JJ, Rosen DL, Parker SD. Multilevel challenges to engagement in HIV care after prison release: a theory-informed qualitative study comparing prisoners' perspectives before and after community reentry. BMC Public Health. 2014;14:1253.

Lim S, Nash D, Hollod L, Harris TG, Lennon MC, Thorpe LE. Influence of jail incarceration and homelessness patterns on engagement in HIV care and HIV viral suppression among new York City adults living with HIV/AIDS. PLoS One. 2015;10(11):e0141912.

Comulada WS, Rotheram-Borus MJ, Pequegnat W, Weiss RE, Desmond KA, Arnold EM, Remien RH, Morin SF, Weinhardt LS, Johnson MO, et al. Relationships over time between mental health symptoms and transmission risk among persons living with HIV. Psychol Addict Behav. 2010;24(1):109–18.

Althoff AL, Zelenev A, Meyer JP, Fu J, Brown S-E, Vagenas P, Avery AK, Cruzado-Quinones J, Spaulding AC, Altice FL. Correlates of retention in HIV care after release from jail: results from a multi-site study. AIDS Behav. 2013;17(2):156–70.

Altice FL, Kamarulzaman A, Soriano VV, Schechter M, Friedland GH. Treatment of medical, psychiatric, and substance-use comorbidities in people infected with HIV who use drugs. Lancet. 2010;376(9738):367–87.

Aaron E, Blum C, Seidman D, Hoyt MJ, Simone J, Sullivan M, Smith DK. Optimizing delivery of HIV Preexposure prophylaxis for women in the United States. AIDS Patient Care STDs. 2018;32(1):16–23.

Sales JM, Sheth AN. Associations among perceived HIV risk, behavioral risk and interest in PrEP among black women in the southern US. AIDS Behav. 2018. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10461-018-2333-9.

Dyer TP, Regan R, Pacek LR, Acheampong A, Khan MR. Psychosocial vulnerability and HIV-related sexual risk among men who have sex with men and women in the United States. Arch Sex Behav. 2015;44(2):429–41.

Friedman SR, Aral S. Social networks, risk-potential networks, health, and disease. J Urban Health. 2001;78(3):411–8.

Spaulding A, Lubelczyk RB, Flanigan T. Can unsafe sex behind bars be barred? Am J Public Health. 2001;91(8):1176–7.

Vlahov D, Putnam S. From corrections to communities as an HIV priority. J Urban Health. 2006;83(3):339–48.

Macalino GE, Vlahov D, Sanford-Colby S, Patel S, Sabin K, Salas C, Rich JD. Prevalence and incidence of HIV, hepatitis B virus, and hepatitis C virus infections among males in Rhode Island prisons. Am J Public Health. 2004;94(7):1218–23.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Tanner Nassau and Melissa Miller for their contribution to the conduct of the study.

Funding

JA supported by grant F31-MH114736-01A1. BM supported in part by DP2-DA040236. MK is supported in part by grants R01-DA044037 and P30-DA01141. ML is supported in part by grants R01-MH106600–01 and R24-HD077976. These funding bodies had no role in the design of the study and collection, analysis, and interpretation of data and in writing the manuscript.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets supporting the conclusions of this article are available through the Brown Digital Repository [https://doi.org/10.26300/bwqx-ax07].

Disclaimer

The views expressed in this article are those of the authors. No official endorsement by the Philadelphia Department of Public Health, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), or National Institutes of Health is intended or should be inferred.

This work was presented at the 9th International AIDS Society (IAS) Conference on HIV Science in Paris, France from July 20–23, 2017.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

BDLM, SG, and SRF conceptualized the TITIAN model. JA, BDLM, and MNL conceptualized this specific analysis. MRFK programmed and calibrated the computer simulation, JA and MRFK performed the formal analysis. KAB managed the surveillance teams which curated the data. MRK, SG, SRF assisted in parameterizing the model. JA wrote the resulting manuscript while MNL, SG, SRF, MRK, and BDLM provided feedback and edits. All authors reviewed and approved submission.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable, all data used within the study are publicly available.

Consent for publication

Not applicable

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Additional file

Additional file 1:

This Supplemental Material includes additional information regarding the structure, parameterization, and results for the agent-based model. The model description follows the ODD (Overview, Design concepts. (PDF 621 kb)

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Adams, J.W., Lurie, M.N., King, M.R.F. et al. Potential drivers of HIV acquisition in African-American women related to mass incarceration: an agent-based modelling study. BMC Public Health 18, 1387 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-018-6304-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-018-6304-x