Abstract

Background

Data on the prevalence of insomnia symptoms in medical outpatient clinics in China are lacking. This study examined the prevalence of insomnia symptoms and their socio-demographic correlates in patients treated at medical outpatient clinics affiliated with four general hospitals in Guangzhou, a large metropolis in southern China.

Method

A total of 4399 patients were consecutively invited to participate in the study. Data on insomnia and its socio-demographic correlates were collected with standardized questionnaires.

Results

The prevalence of any type of insomnia symptoms was 22.1% (95% confidence interval (CI): 20.9–23.3%); the prevalence of difficulty initiating sleep was 14.3%, difficulty maintaining sleep was 16.2%, and early morning awakening was 12.4%. Only 17.5% of the patients suffering from insomnia received sleeping pills. Multiple logistic regression analysis revealed that male gender, education level, rural residence, and being unemployed or retired were negatively associated with insomnia symptoms, while lacking health insurance, older age and more severe depressive symptoms were positively associated with insomnia symptoms.

Conclusions

Insomnia symptoms are common in patients attending medical outpatient clinics in Guangzhou. Increasing awareness of sleep hygiene measures, regular screening and psychosocial and pharmacological interventions for insomnia are needed in China.

Trial registration

ChiCTR-INR-16008066. Registered 8 March 2016.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Insomnia symptoms, including difficulty initiating sleep (DIS), difficulty maintaining sleep (DMS) and early morning awakening (EMA), are major health problems worldwide [1,2,3,4]. Insomnia is associated with daytime fatigue, reduced activity, absenteeism, poor quality of life (QOL), and significant medical and societal costs [5, 6]. The prevalence of sleep problems in the general population ranges from 6 to 76.3% across various countries using different time-frame, measurements and sampling methods [7,8,9,10]. Commonly reported contributing factors to insomnia symptoms include advanced age, female gender, low personal income and educational level, and psychiatric or somatic conditions [9, 11, 12].

In order to develop preventive strategies and allocate health resources, it is important to examine the prevalence of insomnia symptoms. In Western countries the prevalence of insomnia symptoms has been extensively examined in both the general population [13] and medical conditions, such as epilepsy [14] and stroke [15]. Sociocultural and economic factors play an important role in determining the duration and quality of sleep [16, 17]. Therefore, characteristics of insomnia symptoms need to be examined in ethnically and socio-culturally diverse populations. In China, patterns of insomnia symptoms in the general population have been well-documented. A recent meta-analysis of 17 studies found that the pooled prevalence of insomnia symptoms in the Chinese general population was 15.0% [1].

Patients treated in medical outpatient clinics usually have insomnia symptoms resulting in poor sleep quality [18]. A cohort study from 1999 to 2010 found there was a significant increase in prevalence of sleep problems in hospital outpatients [19]. The prevalence of insomnia symptoms in outpatient clinics has been mixed across studies [12, 20]. For example, the prevalence of insomnia symptoms was 11.7% in Japanese (n = 6277) general hospital outpatients [12] while the corresponding figure was 38.5% in China [20].

Data on insomnia symptoms in patients attending medical outpatient clinics their related risk factors are lacking in China. This study aimed to determine the one-month prevalence of different types of insomnia symptoms in Chinese outpatients treated in clinics attached to general hospitals, and also explore their associations with demographic characteristics. In China, there are very few outpatient clinics located in the community; most clinically stable patients with medical conditions attend outpatient clinics attached to general hospitals.

In China, according to the size and specialization of clinical care and research, hospitals are classified into the following three levels [21]: 1. Level-I hospitals are small, community hospitals that only provide basic medical care; 2. Level-II hospitals are regional medical centres that deliver complex health care to patients with severe medical and psychiatric conditions; 3. Level-III hospitals have the highest staff-patient ratio and usually the best medical resources.

Methods

Study sites and participants

This was a multi-center, cross-sectional survey conducted in Guanzhou, a large metropolis in southern China, between March 15, 2016 and June 30, 2016. Patients treated in the neurological, cardiovascular, gastrointestinal, and gynecological outpatient clinics attached to four major level-III hospitals (see Additional file 1) in Guangzhou (the First Affiliated Hospital of Guangzhou University of Traditional Chinese Medicine, Guangzhou Panyu Central Hospital, Nanfang Hospital affiliated with Southern Medical University, and the Third Affiliated Hospital of Sun Yet-Sen University) were consecutively invited to participate in the study if they fulfilled the following inclusion criteria: (1) age of 18 years or above; (2) ability to communicate in Chinese (Mandarin or Cantonese) and (3) understand the purpose and content of the survey.

The study protocol was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Affiliated Brain Hospital of Guangzhou Medical University. Written informed consent was obtained from each patient.

Assessments and evaluation

Information on basic socio-demographic characteristics was collected with a questionnaire by trained psychiatrists and PhD students in clinical psychology at the outpatient clinics of the participating hospitals. All investigators attended a training that introduced the study objectives, procedures of the data collection, and ethical issues of the survey.

Information of three basic types of insomnia symptoms occurring in the past month was ascertained by asking three standard questions, that had been used in previous studies [2, 22]: DIS: Did you ever have difficulties in falling sleep?; DMS: ‘Did you ever have difficulties in maintaining sleep?’; and EMA: ‘Did you ever wake up in the middle of the night or early morning and have difficulties in falling asleep again?’. There were three options to reply to these questions: ‘No’, ‘Sometimes’ and ‘Often’. If patients answered “often” to any of the three questions, they were classified into the “suffering from any insomnia symptoms” group.

The presence and severity of depressive symptoms were assessed with the validated Chinese version of the Patient Health Questionnaire 9 (PHQ-9) [23, 24], which has nine items; each was rated from 0 to 3. Higher scores indicated more severe depressive symptoms. The PHQ-9 score of 10 was used as a cut-off for “having depressive symptoms”, which has satisfactory sensitivity (0.77) and specificity (0.76) in Chinese medical outpatients [23]. Anxiety symptoms were evaluated with the validated Chinese version of the 7-item Generalized Anxiety Disorder (GAD-7) [25, 26]. Each item of the GAD-7 was rated from 0 to 3. Higher scores indicated more severe anxiety symptoms. Patients with a GAD-7 total score of 10 was considered as “having anxiety symptoms”; this cut-off point that has good sensitivity (86.2%) and specificity (95.5%) in Chinese population [25].

Statistical analysis

All data were analyzed using the SPSS, Version 20.0 statistical software (SPSS Inc., Chicago, United States). The comparison between patients with and without insomnia symptoms with regard to demographic characteristics was conducted by chi-square tests, two independent samples t-tests or Mann-Whitney U test, as appropriate. Multiple logistic regression analysis with the “Enter” method was performed to determine the independent relationships between insomnia symptoms and socio-demographic variables. Each type of insomnia symptoms was separately entered as the dependent variable, while given the large sample size, all socio-demographic and clinical characteristics were the independent variables. The level of significance was set at 0.05 (two-tailed). As this was an exploratory study, the significance level was not corrected.

Results

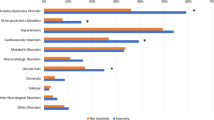

A total of 5284 patients were invited to participate in the survey of whom 4399 completed all the questionnaires yielding a participation rate of 83.3%. The prevalence of any type of insomnia symptoms was 22.1% (95% confidence interval (CI): 20.9–23.3%). The weighted prevalence of any type of insomnia symptoms according to the distribution of patients in the participating hospitals was 21.0% (95% CI: 20.3–21.6%). In the whole sample, the prevalence of DIS, DMS and EMA was 14.3, 16.2 and 12.4%, respectively. Of the 973 patients who reported insomnia symptoms, the percentage of patients with one, two, and three types of insomnia symptoms were 39.6, 27.3, and 33.1%, respectively. Only 17.5% patients (170/973) with insomnia symptoms were taking any type of “sleeping pills (sedatives and hypnotics)”.

Table 1 shows the comparison between patients with and without insomnia symptoms with respect to demographic characteristics. Patients with insomnia symptoms were more likely to be females, older in age, had lower personal income, lower education level, family history of psychiatric disorders, and more severe anxiety and depressive symptoms. Significant differences were also found between the two groups regarding marital and employment status.

In China, the age of ≥50 years has often been used as the cutoff value for “older adults” [27, 28]. Following other studies [27,28,29], the prevalence figures of various types of insomnia symptoms by gender and age groups are listed in Table 2. DIS (14.9% vs. 12.9%), DMS (17.1% vs. 14.4%), and EMA (12.9% vs. 11.2%) were more frequent in females than in males. Compared to younger patients (< 50 years), older patients (>/=50 years) reported more frequent DIS (17.0% vs. 13.1%), DMS (19.8% vs. 14.7%), and EMA (17.2% vs. 10.4%).

Table 3 shows the factors that are independently associated with each type of insomnia symptoms. Male gender, education level, rural residence, and being unemployed or retired were negatively associated with one or more types of insomnia symptoms. Lacking health insurance, older age and more severe depressive symptoms were positively associated with one or more types of insomnia symptoms.

Discussion

This was the first study that examined the prevalence of insomnia symptoms and their association with demographic correlates in Chinese patients attending medical outpatients clinics attached to general hospitals. The prevalence of any type of insomnia symptoms was 22.1%, which is higher than the figure (15.0%) reported in a meta-analysis of 17 general population studies in China [1]. Medical conditions are recognized independent contributors to insomnia [9, 30]. Neurological, cardiovascular, gastrointestinal, and gynecological diseases result in limited physical or outdoor activity, exposure to bright light, and increased daytime sleep, all of which could lead to night-time insomnia symptoms. The prevalence of insomnia symptoms in this study is significantly higher than the figure (11.7%) in Japanese outpatients [12]. Differences across studies could be partly due to inconsistencies in the definitions of insomnia symptoms, time frame (e.g., current, past month, past year or lifetime prevalence), as well as types of physical diseases and sampling methods. Therefore, comparisons of findings across studies should be made with caution.

Only 17.5% of patients with insomnia symptoms in this study reported to taking sleeping pills, which is higher than Chinese nurses (11.7%) [31] and the Chinese general population (5.4%) [9]. The relatively low treatment rate may be attributed to the lack of access to treatment and the reluctance in seeking help among in Chinese people since they generally do not regard insomnia as a medical condition [9, 32].

An independent association between depressive symptoms and insomnia symptoms were found in this study, which is consistent with earlier findings in both Asian [9, 12, 33] and Western settings [7, 30, 34]. However, the causality between depressive and insomnia symptoms could not been identified due to the cross-sectional study design and the fact that poor sleep is a core feature of depressive disorder [35]. As expected, advanced age and lack of health insurance were positively associated with insomnia symptoms.

This study also confirmed prior findings [36, 37] that people who lived in rural settings had less insomnia symptoms than their urban counterparts. In urban areas noise pollution, leisure activities at night, and shift work are frequently unavoidable [37]; in contrast, rural residents are more likely to have frequent outdoor activities and exposure to natural daylight, which could improve sleep quality [38]. Consistent with the earlier findings in general population [9, 39], this study found that insomnia symptoms were associated with lower education level. Persons with lower education level often face greater work-related stress, which may lead to insomnia symptoms. This study did not confirm previous findings that low income [40] was associated with insomnia symptoms.

The results of this study should be treated with caution due to several methodological shortcomings. First, due to logistical reasons, this study was only conducted in outpatient clinics attached to four general hospitals in Guangzhou, therefore, the findings could not be generalized to all patients in the participating hospitals. Second, due to the cross-sectional design, the causality between insomnia symptoms and other variables could not be explored. Third, the sample was heterogeneous in terms of the primary diagnoses and the severity of medical conditions, which could not be controlled for. Fourth, certain measures, such as the presence and frequency of insomnia symptoms, were self-reported, which could be subject to recall bias. Fifth, reasons for outpatient visits were not recorded. In addition, primary sleep disorders other than insomnia symptoms were not examined. Finally, several variables related to insomnia symptoms, such as the presence and severity of medical conditions and primary sleep disorders, sleep quality and the level of sleep hygiene, frequency of nocturnal micturition, use of psychotropic medications, work schedule (such as shifting work), were not collected or evaluated. The strengths of this study include the large sample size and the standardized method of data collection.

Conclusion

Insomnia symptoms are common in Chinese patients attending medical outpatient clinics attached to general hospitals. In particular, older age, female gender, urban residency, employment, lower education level, lack of health insurance, and more severe depressive symptoms appear to increase the risk of insomnia symptoms. Regular screening for insomnia symptoms should be a routine part of care in Chinese outpatient clinics. Sleep hygiene, pharmacotherapy and psychosocial interventions for insomnia symptoms should be given more attention in China. Further surveys are warranted to examine the situation in other parts of China. Longitudinal studies are also needed to determine the demographic and clinical predictors of insomnia symptoms.

Abbreviations

- CI:

-

Confidence interval

- DIS:

-

Difficulty initiating sleep

- DMS:

-

Difficulty maintaining sleep

- EMA:

-

Early morning awakening

- GAD-7:

-

Generalized Anxiety Disorder 7 items

- PHQ-9:

-

Patient Health Questionnaire 9

- QOL:

-

Quality of life

References

Cao XL, Wang SB, Zhong BL, Zhang L, Ungvari GS, Ng CH, Li L, Chiu HF, Lok GK, Lu JP, et al. The prevalence of insomnia in the general population in China: a meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2017;12(2):e0170772.

Liu X, Uchiyama M, Okawa M, Kurita H. Prevalence and correlates of self-reported sleep problems among Chinese adolescents. Sleep. 2000;23(1):27–34.

Morioka H, Itani O, Kaneita Y, Ikeda M, Kondo S, Yamamoto R, Osaki Y, Kanda H, Higuchi S, Ohida T. Associations between sleep disturbance and alcohol drinking: a large-scale epidemiological study of adolescents in Japan. Alcohol (Fayetteville, NY). 2013;47(8):619–28.

Hagg SA, Toren K, Lindberg E. Role of sleep disturbances in occupational accidents among women. Scand J Work Environ Health. 2015;41(4):368–76.

Fullagar HH, Skorski S, Duffield R, Hammes D, Coutts AJ, Meyer T. Sleep and athletic performance: the effects of sleep loss on exercise performance, and physiological and cognitive responses to exercise. Sports medicine (Auckland, NZ). 2015;45(2):161–86.

Scott JP, McNaughton LR, Polman RC. Effects of sleep deprivation and exercise on cognitive, motor performance and mood. Physiol Behav. 2006;87(2):396–408.

Ohayon MM, Lemoine P. A connection between insomnia and psychiatric disorders in the French general population. L'Encephale. 2002;28(5 Pt 1):420–8.

Rocha FL, Guerra HL, Lima-Costa MF. Prevalence of insomnia and associated socio-demographic factors in a Brazilian community: the Bambui study. Sleep Med. 2002;3(2):121–6.

Xiang YT, Ma X, Cai ZJ, Li SR, Xiang YQ, Guo HL, Hou YZ, Li ZB, Li ZJ, Tao YF, et al. The prevalence of insomnia, its sociodemographic and clinical correlates, and treatment in rural and urban regions of Beijing, China: a general population-based survey. Sleep. 2008;31(12):1655–62.

Leger D, Poursain B. An international survey of insomnia: under-recognition and under-treatment of a polysymptomatic condition. Curr Med Res Opin. 2005;21(11):1785–92.

Roth T. Insomnia: definition, prevalence, etiology, and consequences. Journal of clinical sleep medicine : JCSM : official publication of the American Academy of Sleep Medicine. 2007;3(5 Suppl):S7–10.

Ishigooka J, Suzuki M, Isawa S, Muraoka H, Murasaki M, Okawa M. Epidemiological study on sleep habits and insomnia of new outpatients visiting general hospitals in Japan. Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 1999;53(4):515–22.

Ohayon MM, Hong SC. Prevalence of insomnia and associated factors in South Korea. J Psychosom Res. 2002;53(1):593–600.

Camara-Lemarroy CR, Hoyos M, Ibarra-Yruegas BE, Diaz-Torres MA, De Leon R. Affective symptoms and determinants of health-related quality of life in Mexican people with epilepsy. Neurological sciences : official journal of the Italian Neurological Society and of the Italian Society of Clinical Neurophysiology. 2017;

Kim WH, Jung HY, Choi HY, Park CH, Kim ES, Lee SJ, Ko SH, Kim SY, Joa KL. The associations between insomnia and health-related quality of life in rehabilitation units at 1month after stroke. J Psychosom Res. 2017;96:10–4.

Gureje O, Makanjuola VA, Kola L. Insomnia and role impairment in the community : results from the Nigerian survey of mental health and wellbeing. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2007;42(6):495–501.

Ohayon MM, Partinen M. Insomnia and global sleep dissatisfaction in Finland. J Sleep Res. 2002;11(4):339–46.

Institute of Medicine Committee on Sleep M, Research: The National Academies Collection: Reports funded by National Institutes of Health. In: Sleep Disorders and Sleep Deprivation: An Unmet Public Health Problem. EDN Edited by Colten HR, Altevogt BM. Washington (DC): National Academies Press (US) National Academy of Sciences.; 2006.

Ford ES, Wheaton AG, Cunningham TJ, Giles WH, Chapman DP, Croft JB. Trends in outpatient visits for insomnia, sleep apnea, and prescriptions for sleep medications among US adults: findings from the National Ambulatory Medical Care survey 1999-2010. Sleep. 2014;37(8):1283–93.

Wang Z, Lian XY, Zhang XY. Study on cognitive status of insomnia in new outpatients in traditional Chinese medicine clinic [in Chinese]. Chinese Journal for Clinicians. 2016;44(5):107–9.

Linke M, Jankowski KS, Wichniak A, Jarema M, Wykes T. Effects of cognitive remediation therapy versus other interventions on cognitive functioning in schizophrenia inpatients. Neuropsychological rehabilitation. 2017:1–12.

Liu X, Zhou H: Sleep duration, insomnia and behavioral problems among Chinese adolescents. Psychiatry Res 2002, 111(1):75–85.

Xiong N, Fritzsche K, Wei J, Hong X, Leonhart R, Zhao X, Zhang L, Zhu L, Tian G, Nolte S, et al. Validation of patient health questionnaire (PHQ) for major depression in Chinese outpatients with multiple somatic symptoms: a multicenter cross-sectional study. J Affect Disord. 2015;174:636–43.

Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB. The PHQ-9: validity of a brief depression severity measure. J Gen Intern Med. 2001;16(9):606–13.

He XY, Li CB, Qian J, Cui HS, Wu WY. Reliability and validity of a generalized anxiety disorder scale in general hospital outpatient. Shanghai Archives of Psychiatry. 2010;22:200–3.

Spitzer RL, Kroenke K, Williams JB, Lowe B. A brief measure for assessing generalized anxiety disorder: the GAD-7. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166(10):1092–7.

Xiang YT, Buchanan RW, Ungvari GS, Chiu HF, Lai KY, Li YH, Si TM, Wang CY, Lee EH, He YL, et al. Use of clozapine in older Asian patients with schizophrenia between 2001 and 2009. PLoS One. 2013;8(6):e66154.

Kuok KCF, Li L, Xiang YT, Nogueira B, Ungvari GS, Ng CH, Chiu HFK, Tran L, Meng LR. Quality of life and clinical correlates in older adults living in the community and in nursing homes in Macao. Psychogeriatrics : the official journal of the Japanese Psychogeriatric Society. 2017;17(3):194–9.

Dassori AM, Copeland LA, Zeber JE, Miller AL. Factors in second-generation antipsychotic switching patterns in a national sample of older veterans with schizophrenia. Psychiatric services (Washington, DC). 2011;62(1):47–53.

Ford DE, Kamerow DB. Epidemiologic study of sleep disturbances and psychiatric disorders. An opportunity for prevention? Jama. 1989;262(11):1479–84.

An FR, Qi YK, Zeng JY, Ding YM, Chiu HF, Ungvari GS, Newhouse R, Yu DS, Lai KY, Xiang YT. The prevalence of insomnia, its demographic correlates, and treatment in nurses working in Chinese psychiatric and general hospitals. Perspectives in psychiatric care. 2016;52(2):88–94.

Jin LH. Analysis and treatment of insomnia. Chinese Health Care. 2008;8:381.

Su TP, Huang SR, Chou P. Prevalence and risk factors of insomnia in community-dwelling Chinese elderly: a Taiwanese urban area survey. The Australian and New Zealand journal of psychiatry. 2004;38(9):706–13.

Morphy H, Dunn KM, Lewis M, Boardman HF, Croft PR. Epidemiology of insomnia: a longitudinal study in a UK population. Sleep. 2007;30(3):274–80.

Anderson KN, Bradley AJ. Sleep disturbance in mental health problems and neurodegenerative disease. Nature and science of sleep. 2013;5:61–75.

Gu D, Sautter J, Pipkin R, Zeng Y. Sociodemographic and health correlates of sleep quality and duration among very old Chinese. Sleep. 2010;33(5):601–10.

Yang QZ, Bu YQ, Dong SY, Fan SS, Wang LX. A comparison of sleeping problems in school-age children between rural and urban communities in China. J Paediatr Child Health. 2009;45(7–8):414–8.

Ursin R, Bjorvatn B, Holsten F. Sleep duration, subjective sleep need, and sleep habits of 40- to 45-year-olds in the Hordaland health study. Sleep. 2005;28(10):1260–9.

Bixler EO, Kales A, Soldatos CR, Kales JD, Healey S. Prevalence of sleep disorders in the Los Angeles metropolitan area. Am J Psychiatry. 1979;136(10):1257–62.

Hirotsu C, Bittencourt L, Garbuio S, Andersen ML, Tufik S. Sleep complaints in the Brazilian population: impact of socioeconomic factors. Sleep science (Sao Paulo, Brazil). 2014;7(3):135–42.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank all participating hospitals and clinicians for their contribution to the study.

Funding

The study was supported by the Major Projects of the Guangzhou Medical and Health Science and Technology (20151A031003) and the “Precision Medical Research” 2016 Project of the National Key Research and Development Plan (2016YFC0906302). These funding bodies played no direct role in study design, data collection, analyses, and interpretation, manuscript preparation and the decision to submit the article for publication.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analyzed in the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Study Design: YPN. Data collection: WZ, XNL, HYL, XYK, QD, CJZ. Analysis and interpretation of data: WZ, YTX. Drafting of the manuscript: WZ, YTX. Critical revision of the manuscript: CHN, GSU. Approval of the final version for publication: All the authors.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Written informed consent was obtained from each subject. The research was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Affiliated Brain Hospital of Guangzhou Medical University.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Additional file

Additional file 1:

The number of patients from the four outpatient clinics. (DOCX 31 kb)

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Zheng, W., Luo, XN., Li, HY. et al. Prevalence of insomnia symptoms and their associated factors in patients treated in outpatient clinics of four general hospitals in Guangzhou, China. BMC Psychiatry 18, 232 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-018-1808-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-018-1808-6