Abstract

Background

Despite a World Health Organization recommendation for exclusive breastfeeding of all full-term infants to 6 months of age, it is not clear what the health implications may be. Breast milk alone may not meet the nutrition needs for all growing infants, leaving them at risk for deficiencies. The objective of this study was to investigate the relationship between moderate (4 months) versus late (6 months) introduction of complementary foods to the full-term breastfed infant on iron status and growth.

Methods

An electronic search of peer-reviewed and gray-literature was conducted for randomized control trials (RCTs) and observational studies related to the timing of introduction of complementary foods. Iron status and growth data from the relevant RCTs were analyzed using RevMan 5.2.11.

Results

Three RCTs and one observational study met the inclusion criteria. Meta-analysis showed significantly higher hemoglobin levels in infants fed solids at 4 months versus those fed solids at 6 months in developing countries [mean difference [MD]: 5.0 g/L; 95 % CI: 1.5, 8.5 g/L; P = 0.005]. Meta-anaysis also showed higher serum ferritin levels in the 4-month group in both developed and developing countries [MD: 26.0 μg/L; 95 % CI: -0.1, 52.1 μg/L, P = 0.050], [MD: 18.9 μg/L; 95 % CI: 0.7, 37.1 μg/L, P = 0.040]. Short follow-up periods and small sample sizes of the included studies were the major limitations.

Conclusions

RCT evidence suggests the rate of iron deficiency anemia in breastfed infants could be positively altered by introduction of solids at 4 months.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

The World Health Organization (WHO) currently recommends exclusively breastfeeding infants for the first 6 months of life, followed by introduction of adequate complementary foods (CF). This recommendation is for infants living in developing and developed countries, including Canada [1, 2]. Although there is nearly universal agreement that breast milk alone is the optimal first food, the age range in which solids should be introduced is less clear, leading to “weanling’s dilemma” [3].

The complementary feeding period accompanies a critical window of vulnerability. During this time period, failure to grow is a significant concern [4]. Micronutrient deficiencies can also occur during this period, mostly because infants have higher nutrient demands relative to increased energy requirements. Deficiencies of certain micronutrients such as iron result in potentially irreversible negative effects on brain development and other detrimental psychological outcomes [5]. There is general, but not universal, agreement that the iron stores of infants start to deplete at about 6 months of age, leaving the infants at high risk of iron deficiency and iron deficiency anemia. This is especially true among exclusively breastfed infants [6, 7]. The estimated prevalence of iron deficiency anemia among Canadian children aged 1–5 years is 5 % and was found to be five times higher among Inuit children [8, 9]. Therefore, it is important to determine the ideal age to introduce iron-rich CF. Our objectives were to evaluate the current scientific evidence and to investigate the relationship between time of introduction of CF with iron status and growth in breastfed infants. This review includes any relevant studies that targeted exclusively breastfed infants between 4 and 6 months of age.

Methods

Our review was conducted according to the PRISMA guidelines [10]. The Cochrane Risk of Bias Tool [11] was used to assess study quality by the two reviewers. Any disagreements were resolved through discussion.

Literature search

Electronic searches of the MEDLINE and CINHAL databases were used to identify publications regarding the timing of introduction of CF. The searches were completed by two authors (WQ, TRF) in May, 2014. Medical subject headings and text keywords used to search included: complementary feeding, infant food, solid(s), weaning, timing of introduction, micronutrient, iron, developmental outcomes, iron supplementation, random allocation, cohort studies, follow up studies, prospective studies, cross over studies, and cross sectional studies. To decrease the chance of publication bias influencing the results, TRF conducted a gray literature search to include studies that may not be included in bibliographic retrieval systems. Google, Current Controlled Trials, NIH Clinical Research Trials, ISRCTN, and Cochrane Register of Clinical Trials were also searched up to May, 2014.

Inclusion criteria

We included any randomized controlled trials (RCTs) and observational studies that focused on introduction of CF at 4 months versus 6 months of age. All included studies were conducted on healthy, full-term, exclusively breastfed infants.

Exclusion criteria

Studies were excluded if they included formula-fed, preterm, or low birth weight infants or involved medicinal iron supplementation. Studies in which infants were introduced to solid foods at ages younger than 4 months or greater than 6 months of age were also excluded.

Data analysis

Meta-analyses were performed on all of the iron and growth data from included RCTs, regardless of the number of RCTs, following Kramer and Kakuma’s systematic review approach [12]. Weighted mean difference meta-analysis was carried out using Review Manager software (RevMan Version 5.2.11, The Cochrane Collaboration, London, UK) [13] to assess the effect of age of introduction of solids on iron status and linear growth (weight, length and head circumference). The analyses were stratified by developing versus developed country and by study design (e.g., randomized controlled trials versus observational studies).

Results

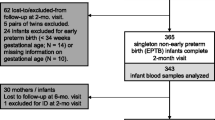

A total of 923 study citations were found related to age of complementary feeding (Fig. 1). Twenty-five RCTs were found, only three of which met the inclusion criteria. One was conducted in a developed country (generating two separate publications), and two were in developing countries (Table 1). Forty-seven observational studies examining the age of introduction of CF were located. Only one of the observational studies (in a developing country) met the inclusion criteria (Table 1). Table 2 lists the excluded studies and the reasons for their exclusion.

Iron

A total of two RCTs assessed iron status outcomes (Table 1). Meta-analysis (Fig. 2.1) suggested that introduction of solids at 4 months of age did not improve hemoglobin status of breastfed infants in developed countries compared with introduction at 6 months of age [mean difference [MD]: 0.2 g/L; 95 % CI: -2.4, 2.8 g/L; P = 0.88]. In developing countries, however (Fig. 3.1), significant improvement was detected with the earlier introduction of solids [MD: 5.0 g/L; 95 % CI: 1.5, 8.5 g/L; P = 0.005]. Plasma ferritin concentration was improved with introduction of solids at 4 months of age for infants living in both developed and developing countries [MD: 26.0 μg/L; 95 % CI: −0.1, 52.1 μg/L, P = 0.050], [MD: 18.9 μg/L; 95 % CI: 0.7, 37.1 μg/L, P = 0.040] (Figs. 2.2 & 3.2). The included observational study did not include iron parameters.

Growth

Growth was assessed by differences in weight, length and head circumference. Three [14–16] of the included four interventional studies reported on the impact of introduction of solids on growth (Table 1). The meta-analyses showed a non-significant effect of earlier CF introduction on growth in both developing and developed countries on weight, length and head circumference (Figs. 4, 5, 6, and 7). In addition, the study by Wells et al. (Table 1) showed non-significant differences between the two groups in body composition (lean mass, P = 0.4, fat mass, P = 0.14).

There was no association between early introduction of complementary foods and a difference in weight and/or length in the study conducted in a developing country (P = 0.95, P = 0.86, respectively) [17].

Risk of bias within studies

We assessed the included trials for risk of bias as described in the method section (Table 3). The older studies had moderate risk of bias due to lack of reporting for sequence generation, concealment allocation, and blinding [14, 18]. The two more recent trials [15, 16] had no apparent risk of bias.

Discussion

In this meta-analysis, we found that infants in developing countries who were introduced to solid foods at 4 months of age had clinically relevant increases in hemoglobin and ferritin levels, compared with exclusively breastfed infants at 6 months of age. The data from developed countries showed only a significant increase in ferritin levels in the infants exposed to CF earlier. Our meta-analysis indicated that there was no significant impact of earlier introduction of solids on growth for either developed or developing countries, as evident by a lack of significant differences in weight, length or head circumference measures.

To our knowledge, this is the first systematic review to evaluate the effects of complementary food introduction at 4 versus 6 months of age on iron status and growth. Other reviews have examined the effect of iron-fortified food on iron status and anemia rates on children of different ages [19]. Dewey and Adu-Afaruah reviewed existing studies that looked at the effects of CF on various biochemical and functional outcomes, but they did not evaluate solids introduction at 4 versus 6 months [20]. Systematic reviews/meta-analyses assessing the effect of iron supplementation/fortification in infants and childeren suggest a benefit in the improvement of hematologic iron markers but iron supplementation may not significantly improve growth and neuromotor development [21–24]. It is important to consider the effects of iron rich food on iron status and growth, along with the possible risk of infections, particularly in developing countries where water supplies may not be safe [25]. Our findings regarding growth are in line with that of Kramer and Kakuma, who found non-significant differences in linear growth in infants introduced to solids before 4 months and those breastfed until 6 months, and on which the WHO recommendation was largely based [12]. We identified only one observational study that opposed the findings of Kramer and Kakuma. It assessed the effect of introducing CF at exactly 4 months of age versus 6 months. This finding is due to our stricter criteria, as these are the controversial time points that most of the organizations’ recommendations fit in. A previous systematic review identified significant growth improvements with provision of solid foods [26, 27], but this review included studies conducted on moderately malnourished infants, where the ones included in our review were all healthy.

More evidence is needed to agree on the optimal timing of introduction of solids to exclusively breastfed infants. In future studies, ideally multi-center ones with long-term follow up, special attention should be given to hematological results to achieve a definitive conclusion on this important issue.

Limitations

The included studies had short follow-up periods in which to measure the impact of complementary food introduction. Longer term outcomes remain uncertain. Another limitation of our review is the inclusion of studies with small sample sizes. Finally, pooled data analyses could not be performed for all the outcomes due to the differences in the outcome measures assessed in the individual studies.

Conclusion

Encouraging exclusive breastfeeding is a desirable goal for health care professionals as there is consistent evidence to support breastfeeding. However, the generalized recommendation to introduce solid foods at 6 months of age may not be optimum for all healthy, breastfed infants. Based on the findings of this review, the iron status of healthy full-term infants could be positively altered by an earlier introduction of complementary foods, leading to preservation of infant iron stores. Furthermore, there may be value in changing the current statement regarding solid introduction from a fixed time (6 months) to a range of time (4–6 months), leaving individual decisions to health care professionals and parents. Larger randomized controlled multi-center trials in developed and developing countries are needed to further investigate the differences in outcomes after introduction of solids before and at 6 months of age.

Abbreviations

- CF:

-

Complemenatry food

- MD:

-

Mean difference

- RCT:

-

Randomized controlled trial

References

World Health Organization. Infant and young child feeding. 2010. http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs342/en/. Accessed November 17 2013.

Health Canada. Nutrition for healthy term infants: recommendations from birth to six months. Can J Diet Pract Res. 2012;73:204.

Rowland MG. The weanling’s dilemma: are we making progress? Acta Paediatr Scand Suppl. 1986;323:33–42.

Shrimpton R, Victora CG, de Onis M, Lima RC, Blossner M, Clugston G. Worldwide timing of growth faltering: implications for nutritional interventions. Pediatrics. 2001;107:E75.

Lozoff B, Beard J, Connor J, Barbara F, Georgieff M, Schallert T. Long-lasting neural and behavioral effects of iron deficiency in infancy. Nutr Rev. 2006;64:S34–43. discussion S72-91.

Butte NFL-A, M. G. Garza, C. Nutrient adequacy of exclusive breastfeeding for the term infant during the first six months of life. Geneva. World Health Organization. 2002. http://www.who.int/nutrition/publications/infantfeeding/9241562110/en/. Accessed November 17 2013.

Meinzen-Derr JK, Guerrero ML, Altaye M, Ortega-Gallegos H, Ruiz-Palacios GM, Morrow AL. Risk of infant anemia is associated with exclusive breast-feeding and maternal anemia in a Mexican cohort. J Nutr. 2006;136:452–8.

Christofides A, Schauer C, Zlotkin SH. Iron deficiency and anemia prevalence and associated etiologic risk factors in First Nations and Inuit communities in Northern Ontario and Nunavut. Can J Public Health. 2005;96:304–7.

Willows ND, Dewailly E, Gray-Donald K. Anemia and iron status in Inuit infants from northern Quebec. Can J Public Health. 2000;91:407–10.

Liberati A, Altman DG, Tetzlaff J, Mulrow C, Gotzsche PC, Ioannidis JP, et al. The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate health care interventions: explanation and elaboration. J Clin Epidemiol. 2009;62:e1–34. doi:10.1016/j.jclinepi.2009.06.006.

Higgins JP, Altman DG, Gotzsche PC, Juni P, Moher D, Oxman AD, et al. The Cochrane Collaboration’s tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. BMJ. 2011;343:d5928.

Kramer MS, Kakuma R. Optimal duration of exclusive breastfeeding. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;8:CD003517. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD003517.pub2.

Cochrane Collaboration, Review Manager (RevMan version 5.2). 2012. http://tech.cochrane.org/revman. Accessed May 29 2014.

Cohen RJ, Brown KH, Canahuati J, Rivera LL, Dewey KG. Effects of age of introduction of complementary foods on infant breast milk intake, total energy intake, and growth: a randomised intervention study in Honduras. Lancet. 1994;344:288–93.

Jonsdottir OH, Thorsdottir I, Hibberd PL, Fewtrell MS, Wells JC, Palsson GI, et al. Timing of the introduction of complementary foods in infancy: a randomized controlled trial. Pediatrics. 2012;130:1038–45. doi:10.1542/peds.2011-3838.

Wells JC, Jonsdottir OH, Hibberd PL, Fewtrell MS, Thorsdottir I, Eaton S, et al. Randomized controlled trial of 4 compared with 6 mo of exclusive breastfeeding in Iceland: differences in breast-milk intake by stable-isotope probe. Am J Clin Nutr. 2012;96:73–9. doi:10.3945/ajcn.111.030403.

Khadivzadeh T, Parsai S. Effect of exclusive breastfeeding and complementary feeding on infant growth and morbidity. East Mediterr Health J. 2004;10:289–94.

Dewey KG, Cohen RJ, Rivera LL, Brown KH. Effects of age of introduction of complementary foods on iron status of breast-fed infants in Honduras. Am J Clin Nutr. 1998;67:878–84.

Eichler K, Wieser S, Ruthemann I, Brugger U. Effects of micronutrient fortified milk and cereal food for infants and children: a systematic review. BMC Public Health. 2012;12:506. doi:10.1186/1471-2458-12-506.

Dewey KG, Adu-Afarwuah S. Systematic review of the efficacy and effectiveness of complementary feeding interventions in developing countries. Matern Child Nutr. 2008;4 Suppl 1:24–85. doi:10.1111/j.1740-8709.2007.00124.x.

De-Regil LM, Suchdev PS, Vist GE, Walleser S, Pena-Rosas JP. Home fortification of foods with multiple micronutrient powders for health and nutrition in children under two years of age (Review). Evid Based Child Health. 2013;8(1):112–201.

Gera T, Sachdev HP, Nestel P, Sachdev SS. Effect of iron supplementation on haemoglobin response in children: systematic review of randomised controlled trials. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2007;44(4):468–86.

Ramakrishnan U, Aburto N, McCabe G, Martorell R. Multimicronutrient interventions but not vitamin a or iron interventions alone improve child growth: results of 3 meta-analyses. J Nutr. 2004;134(10):2592–602.

Sachdev H, Gera T, Nestel P. Effect of iron supplementation on mental and motor development in children: systematic review of randomised controlled trials. Public Health Nutr. 2005;8(2):117–32.

Pasricha SR, Drakesmith H, Black J, Hipgrave D, Biggs BA. Control of iron deficiency anemia in low- and middle-income countries. Blood. 2013;121(14):2607–17.

Imdad A, Yakoob MY, Bhutta ZA. Impact of maternal education about complementary feeding and provision of complementary foods on child growth in developing countries. BMC Public Health. 2011;11 Suppl 3:S25. doi:10.1186/1471-2458-11-S3-S25.

Bhutta ZA, Ahmed T, Black RE, Cousens S, Dewey K, Giugliani E, et al. What works? Interventions for maternal and child undernutrition and survival. Lancet. 2008;371:417–40.

Adu-Afarwuah S, Lartey A, Brown KH, Zlotkin S, Briend A, Dewey KG. Randomized comparison of 3 types of micronutrient supplements for home fortification of complementary foods in Ghana: effects on growth and motor development. Am J Clin Nutr. 2007;86:412–20.

Bisimwa G, Owino VO, Bahwere P, Dramaix M, Donnen P, Dibari F, et al. Randomized controlled trial of the effectiveness of a soybean-maize-sorghum-based ready-to-use complementary food paste on infant growth in South Kivu, Democratic Republic of Congo. Am J Clin Nutr. 2012;95:1157–64. doi:10.3945/ajcn.111.028704.

Fewtrell MS, Kennedy K, Nicholl R, Khakoo A, Lucas A. Infant feeding bottle design, growth and behaviour: results from a randomised trial. BMC Res Notes. 2012;5:150. doi:10.1186/1756-0500-5-150.

Gibson RS, Kafwembe E, Mwanza S, Gosset L, Bailey KB, Mullen A, et al. A micronutrient-fortified food enhances iron and selenium status of Zambian infants but has limited efficacy on zinc. J Nutr. 2011;141:935–43. doi:10.3945/jn.110.135228.

Hambidge SJ, Davidson AJ, Phibbs SL, Chandramouli V, Zerbe G, LeBaron CW, et al. Strategies to improve immunization rates and well-child care in a disadvantaged population: a cluster randomized controlled trial. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2004;158:162–9. doi:10.1001/archpedi.158.2.162.

Krebs NF, Hambidge KM, Mazariegos M, Westcott J, Goco N, Wright LL, et al. Complementary feeding: a Global Network cluster randomized controlled trial. BMC Pediatr. 2011;11:4. doi:10.1186/1471-2431-11-4.

Ly CT, Diallo A, Simondon F, Simondon KB. Early short-term infant food supplementation, maternal weight loss and duration of breast-feeding: a randomised controlled trial in rural Senegal. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2006;60:265–71. doi:10.1038/sj.ejcn.1602311.

Martin-Calama J, Bunuel J, Valero MT, Labay M, Lasarte JJ, Valle F, et al. The effect of feeding glucose water to breastfeeding newborns on weight, body temperature, blood glucose, and breastfeeding duration. J Hum Lact. 1997;13:209–13.

Mehta KC, Specker BL, Bartholmey S, Giddens J, Ho ML. Trial on timing of introduction to solids and food type on infant growth. Pediatrics. 1998;102:569–73.

Mosley C, Whittle C, Hicks C. A pilot study to assess the viability of a randomised controlled trial of methods of supplementary feeding of breast-fed pre-term babies. Midwifery. 2001;17:150–7. doi:10.1054/midw.2000.0244.

Nicoll A, Ginsburg R, Tripp JH. Supplementary feeding and jaundice in newborns. Acta Paediatr Scand. 1982;71:759–61.

Ojofeitimi EO, Elegbe IA. The effect of early initiation of colostrum feeding on proliferation of intestinal bacteria in neonates. Clin Pediatr (Phila). 1982;21:39–42.

Phuka JC, Maleta K, Thakwalakwa C, Cheung YB, Briend A, Manary MJ, et al. Complementary feeding with fortified spread and incidence of severe stunting in 6- to 18-month-old rural Malawians. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2008;162:619–26. doi:10.1001/archpedi.162.7.619.

Rivera JA, Sotres-Alvarez D, Habicht JP, Shamah T, Villalpando S. Impact of the Mexican program for education, health, and nutrition (Progresa) on rates of growth and anemia in infants and young children: a randomized effectiveness study. JAMA. 2004;291:2563–70. doi:10.1001/jama.291.21.2563.

Roy. Feasible Means to Address Moderately Malnourished Children Within BINP Communities. 2006. http://clinicaltrials.gov/show/NCT00372242.

Sachdev HP, Krishna J, Puri RK, Satyanarayana L, Kumar S. Water supplementation in exclusively breastfed infants during summer in the tropics. Lancet. 1991;337:929–33.

Saleem. Maternal Education on Complementary Feeding and Infant Outcome. 2010. http://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT01128517?term=saleem&rank=5.

Sarker. Ferrous Fumarate and Ferric Pyrophosphate as Food Fortificants in Developing Countries. 2009. http://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT00867867?term=ferrous&rank=3.

Schutzman DL, Hervada AR, Branca PA. Effect of water supplementation of full-term newborns on arrival of milk in the nursing mother. Clin Pediatr (Phila). 1986;25:78–80.

Simondon KB, Gartner A, Berger J, Cornu A, Massamba JP, San Miguel JL, et al. Effect of early, short-term supplementation on weight and linear growth of 4-7-mo-old infants in developing countries: a four-country randomized trial. Am J Clin Nutr. 1996;64:537–45.

Ziegler EE, Nelson SE, Jeter JM. Iron status of breastfed infants is improved equally by medicinal iron and iron-fortified cereal. Am J Clin Nutr. 2009;90:76–87. doi:10.3945/ajcn.2008.27350.

Ahmed F, Clemens JD, Rao MR, Khan MR, Haque E. Initiation of food supplements and stopping of breast-feeding as determinants of weanling shigellosis. Bull World Health Organ. 1993;71:571–8.

Armar-Klemesu MA, Wheeler EF, Brakohiapa LA, Yamamoto S. Infant feeding and growth in rural Ghana: is the use of the traditional fermented porridge a case for early supplementation? J Trop Pediatr. 1991;37:111–5.

Arvas A, Elgormus Y, Gur E, Alikasifoglu M, Celebi A. Iron status in breast-fed full-term infants. Turk J Pediatr. 2000;42:22–6.

Baker JL, Michaelsen KF, Rasmussen KM, Sorensen TI. Maternal prepregnant body mass index, duration of breastfeeding, and timing of complementary food introduction are associated with infant weight gain. Am J Clin Nutr. 2004;80:1579–88.

Baird J, Poole J, Robinson S, Marriott L, Godfrey K, Cooper C, et al. Milk feeding and dietary patterns predict weight and fat gains in infancy. Paediatr Perinat Epidemiol. 2008;22:575–86. doi:10.1111/j.1365-3016.2008.00963.x.

Calvo EB, Galindo AC, Aspres NB. Iron status in exclusively breast-fed infants. Pediatrics. 1992;90:375–9.

Castro TG, Baraldi LG, Muniz PT, Cardoso MA. Dietary practices and nutritional status of 0-24-month-old children from Brazilian Amazonia. Public Health Nutr. 2009;12:2335–42. doi:10.1017/S1368980009004923.

Chantry CJ, Howard CR, Auinger P. Full breastfeeding duration and risk for iron deficiency in U.S. infants. Breastfeed Med. 2007;2:63–73. doi:10.1089/bfm.2007.0002.

Domellof M, Cohen RJ, Dewey KG, Hernell O, Rivera LL, Lonnerdal B. Iron supplementation of breast-fed Honduran and Swedish infants from 4 to 9 months of age. J Pediatr. 2001;138:679–87. doi:10.1067/mpd.2001.112895.

Dube K, Schwartz J, Mueller MJ, Kalhoff H, Kersting M. Iron intake and iron status in breastfed infants during the first year of life. Clin Nutr. 2010;29:773–8. doi:10.1016/j.clnu.2010.05.002.

Dura Trave T, Diaz Velaz L. Prevalence of iron deficiency in healthy 12-month-old infants. An Esp Pediatr. 2002;57:209–14.

Eissa AM, El-sherbini AF, Khashaba AA, El-bakry M, Abou Amer ER. Breast feeding and infant growth, a follow-up study in Menoufia. Egypt Popul Sci. 1990;9:69–75.

Filipiak B, Zutavern A, Koletzko S, von Berg A, Brockow I, Grubl A, et al. Solid food introduction in relation to eczema: results from a four-year prospective birth cohort study. J Pediatr. 2007;151:352–8. doi:10.1016/j.jpeds.2007.05.018.

Forsyth JS, Ogston SA, Clark A, Florey CD, Howie PW. Relation between early introduction of solid food to infants and their weight and illnesses during the first two years of life. BMJ. 1993;306:1572–6.

Freeman VE, Mulder J, van't Hof MA, Hoey HM, Gibney MJ. A longitudinal study of iron status in children at 12, 24 and 36 months. Public Health Nutr. 1998;1:93–100.

Gray SJ. Ecology of weaning among nomadic Turkana pastoralists of Kenya: maternal thinking, maternal behavior, and human adaptive strategies. Hum Biol. 1996;68:437–65.

Haschke F, Van't Hof MA. Euro-Growth references for breast-fed boys and girls: influence of breast-feeding and solids on growth until 36 months of age. Euro-Growth Study Group. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2000;31 Suppl 1:S60–71.

Heinig MJ, Nommsen LA, Peerson JM, Lonnerdal B, Dewey KG. Intake and growth of breast-fed and formula-fed infants in relation to the timing of introduction of complementary foods: the DARLING study. Davis Area Research on Lactation, Infant Nutrition and Growth. Acta Paediatr. 1993;82:999–1006.

Hokama T. Levels of serum ferritin and total body iron among infants with different feeding regimens. Acta Paediatr Jpn. 1993;35:298–301.

Kajosaari M, Saarinen UM. Prophylaxis of atopic disease by six months’ total solid food elimination. Evaluation of 135 exclusively breast-fed infants of atopic families. Acta Paediatr Scand. 1983;72:411–4.

Kajosaari M. Atopy prophylaxis in high-risk infants. Prospective 5-year follow-up study of children with six months exclusive breastfeeding and solid food elimination. Adv Exp Med Biol. 1991;310:453–8.

Kikafunda JK, Lukwago FB, Turyashemererwa F. Anaemia and associated factors among under-fives and their mothers in Bushenyi district, Western Uganda. Public Health Nutr. 2009;12:2302–8. doi:10.1017/S1368980009005333.

Kramer MS, Moodie EE, Dahhou M, Platt RW. Breastfeeding and infant size: evidence of reverse causality. Am J Epidemiol. 2011;173:978–83. doi:10.1093/aje/kwq495.

Lartey A, Manu A, Brown KH, Peerson JM, Dewey KG. A randomized, community-based trial of the effects of improved, centrally processed complementary foods on growth and micronutrient status of Ghanaian infants from 6 to 12 mo of age. Am J Clin Nutr. 1999;70:391–404.

Lopez-Alarcon M, Villalpando S, Fajardo A. Breast-feeding lowers the frequency and duration of acute respiratory infection and diarrhea in infants under six months of age. J Nutr. 1997;127:436–43.

Marlin DW, Picciano MF, Livant EC. Infant feeding practices. J Am Diet Assoc. 1980;77:668–76.

Marquis GS, Habicht JP, Lanata CF, Black RE, Rasmussen KM. Association of breastfeeding and stunting in Peruvian toddlers: an example of reverse causality. Int J Epidemiol. 1997;26:349–56.

Messiah SE, Arheart KL, Lipshultz SE, Bandstra ES, Miller TL. Perinatal factors associated with cardiovascular disease risk among preschool-age children in the United States: an analysis of 1999-2008 NHANES Data. Int J Pediatr. 2012;2012:157237. doi:10.1155/2012/157237.

Nielsen GA, Thomsen BL, Michaelsen KF. Influence of breastfeeding and complementary food on growth between 5 and 10 months. Acta Paediatr. 1998;87:911–7.

Piwoz EG. Creed de Kanashiro H, Lopez de Romana GL, Black RE, Brown KH. Feeding practices and growth among low-income Peruvian infants: a comparison of internationally-recommended definitions. Int J Epidemiol. 1996;25:103–14.

Popkin BM, Adair L, Akin JS, Black R, Briscoe J, Flieger W. Breast-feeding and diarrheal morbidity. Pediatrics. 1990;86:874–82.

Quigley MA, Kelly YJ, Sacker A. Infant feeding, solid foods and hospitalisation in the first 8 months after birth. Arch Dis Child. 2009;94:148–50. doi:10.1136/adc.2008.146126.

Rowland MG, Rowland SG, Cole TJ. Impact of infection on the growth of children from 0 to 2 years in an urban West African community. Am J Clin Nutr. 1988;47:134–8.

Saarinen UM, Siimes MA. Serum ferritin in assessment of iron nutrition in healthy infants. Acta Paediatr Scand. 1978;67:745–51.

Salmenpera L, Perheentupa J, Siimes MA. Exclusively breast-fed healthy infants grow slower than reference infants. Pediatr Res. 1985;19:307–12.

Simondon KB, Simondon F. Age at introduction of complementary food and physical growth from 2 to 9 months in rural Senegal. Eur J Clin Nutr. 1997;51:703–7.

Sloan S, Gildea A, Stewart M, Sneddon H, Iwaniec D. Early weaning is related to weight and rate of weight gain in infancy. Child Care Health Dev. 2008;34:59–64. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2214.2007.00771.x.

Victora CG, Morris SS, Barros FC, Horta BL, Weiderpass E, Tomasi E. Breast-feeding and growth in Brazilian infants. Am J Clin Nutr. 1998;67:452–8.

Wilson AC, Forsyth JS, Greene SA, Irvine L, Hau C, Howie PW. Relation of infant diet to childhood health: seven year follow up of cohort of children in Dundee infant feeding study. BMJ. 1998;316:21–5.

Wilson W, Milner J, Bulkan J, Ehlers P. Weaning practices of the Makushi of Guyana and their relationship to infant and child mortality: a preliminary assessment of international recommendations. Am J Hum Biol. 2006;18:312–24. doi:10.1002/ajhb.20500.

Zhou H, Wang XL, Ye F, Zeng XL, Wang Y. Relationship between child feeding practices and malnutrition in 7 remote and poor counties, P R China. Asia Pac J Clin Nutr. 2012;21:234–40.

Acknowledgements

No funding was received for this work.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declare that the manuscript is original, has not been submitted to or is not under consideration by another publication, and has not been previously published in any format including electronic. The authors declare that the previously published work cited in the manuscript has been fully cited and acknowledged. All authors of this manuscript have contributed substantially to the manuscript and approved the final submission. The authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest and shall disclose any potential conflicts of interest in the future. The authors of this review article declare that there are no financial interests that might have an impact on the views expressed in this article.

Authors’ contributions

WQ conceptualized and designed the study, carried out the initial analyses and the data search, drafted the initial manuscript, and approved the final manuscript as submitted. TF carried out the data search, reviewed and revised the manuscript, and approved the final manuscript as submitted. JF conceptualized and designed the study, and coordinated and supervised data search, critically reviewed the manuscript, and approved the final manuscript as submitted.

Additional file

Additional file 1:

PRISMA 2009 Checklist. (DOC 62 kb)

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Qasem, W., Fenton, T. & Friel, J. Age of introduction of first complementary feeding for infants: a systematic review. BMC Pediatr 15, 107 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12887-015-0409-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12887-015-0409-5