Abstract

Background

Chiari I malformations (CM I) are rare hindbrain herniations. Dysphagia and other oropharyngeal dysfunctions may be associated with CM I, but to our knowledge, no clinical presentation similar to ours has ever been reported. The purpose of this communication is to draw attention to a unique and atypical clinical presentation of a child with CM I.

Case presentation

A 7-year-old boy was evaluated for a two month history of atypical movements which would occur in the evening, and last for an hour after eating. These stereotypical movements with the head and chest bending forward and to the left side, accompanied by a grimace, were associated with sensation of breath locking without cyanosis. Pain and dysphagia were absent. The neurological examination was normal. The possibility of Sandifer syndrome posturing occurring with gastroesopageal reflux disease was considered but neither pain nor back hyperextension were associated with the atypical movements. Neither proton pump inhibitors (PPI) nor prokinetic agents improved his symptoms.

Upper endoscopy and esophageal biopsy did not reveal eosinophilic esophagitis nor reflux esophagitis. Ear, throat and nose (ENT) exam was normal. A severe gastroparesis was demonstrated on milk scan study. Two 24 hour oesophageal pH probe studies pointed out severe gastroesophageal reflux (GER). High resolution manometric evaluation of the oesophagus revealed normal sphincter pressures and relaxations with no dysmotility of the esophageal body. Electroencephalography and polysomnography were normal. A brain magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) was performed and revealed a CM I: cerebellar tonsils extending to 12 mm, with syringomyelia (D4-D5).

For a long period of time, the child’s abnormal movements were considered to be nothing but tics and the CM I a fortuitous finding. Since the child remained symptomatic despite medical treatment, it was decided to proceed with surgery. One year after the onset of his symptoms, he underwent posterior fossa decompression with upper cervical laminectomy and expansion duroplasty. Postoperative MRI confirmed adequate decompression. His atypical posture and dyspnea completely resolved after surgery and he remains asymptomatic two years later.

Conclusion

Children may have atypical presentations of CM I. Thus, CM I diagnosis should be considered in unexplained atypical oropharyngeal dysfunctions.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Chiari I malformations (CM I) are rare hindbrain herniations that may be present in children or adults. CM I is characterized by an abnormal position of the cerebellar tonsils, which herniate outside the cranial cavity into the upper cervical canal: this is associated with an obliteration of the subarachnoid spaces at the level of the foramen magnum [1],[2]. Anomalies associated with CM I include syringomyelia. CM I can be easily identified on magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the cranio-vertebral junction [3]. Tonsillar herniation of 5 mm below the foramen magnum is the most common cut off for radiological diagnosis of CM I [4]. More recently, because of the ease of diagnosis and increased clinical awareness, pediatric cases are increasingly reported [5]. Many studies have reported symptoms such as headaches, scoliosis or neurological troubles which were attributed to compression of neural structures. Dysphagia and other oropharyngeal dysfunctions have also been reported but, to our knowledge, no clinical presentation similar to ours has ever been reported.

The purpose of this communication is to draw attention to a unique and atypical clinical presentation of a child with CM I.

Case presentation

A 7-year-old boy was evaluated for a two month history of atypical movements presenting in the evening, and lasting an hour after eating. These stereotypical movements with the head and chest bending forward and to the left side, accompanied by a grimace were associated with sensation of breath locking without cyanosis. Pain and dysphagia were absent. The neurological examination was normal. The possibility of Sandifer syndrome posturing occurring with gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) was considered but neither pain nor back hyperextension were associated with the atypical movements. PPI did not improve his symptoms. Various prokinetic agents (metoclopramide, motilium, cisapride and erythomycin) were also inefficient.

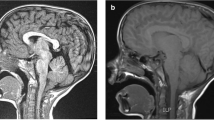

Upper endoscopy and esophageal biopsy did not reveal eosinophilic esophagitis or other abnormalities. ENT exam was normal. A severe gastroparesis was demonstrated on milkscan study. Two 24 hour esophageal pH probe studies pointed out severe GER. High resolution manometric evaluation of the oesophagus revealed normal sphincter pressures and relaxations with no dysmotility of the esophageal body. Electroencephalography and polysomnography were normal. Because of the unexplained dyspnea associated with this abnormal posture, a head MRI was performed and revealed a CM I: cerebellar tonsils extending to 12 mm, with syringomyelia (D4-D5) (Figure 1).

For a long period of time, the child abnormal movements were only considered to be tics and the CM I was considered a fortuitous finding. Since the child remained symptomatic despite medical treatment, it was eventually decided to proceed with surgery. The operative procedure was done one year after the onset of his symptoms. He underwent posterior fossa decompression with upper cervical laminectomy and expansion duroplasty. No postoperative complication occurred. Postoperative MRI confirmed adequate decompression. His atypical posture and dyspnea completely resolved in the week after surgery. More than two years after surgery, the child remains asymptomatic. The patient and parents have refused any further invasive testing (such as a control esophageal pH probe study) as the patient was symptom free.

Discussion

Although CM I is increasingly detected in children [3],[5], much remains unknown about its natural history. The pathophysiology of CM I and its associated anomalies have been the subject of considerable debate [1]. Chiari I is a multifactorial condition that is thought to result from a congenital small posterior fossa. Neurologic signs and symptoms may be related directly to a tight foramen magnum associated with the cerebellar tonsillar herniation, with compression and/or distorsion of the medulla and lower cranial nerves.

In adults, the most common clinical symptoms are posterior headaches and/or neck pain exacerbated by Valsava maneuvers [4]. The clinical presentation of young children with CM I differs from that of older children and adults. Albert et al. showed that patients aged 0 to 2 years were much more likely to have oropharyngeal dysfunction, whereas those aged 3 to 5 years were more likely to have syringomyelia, frequently associated with scoliosis [6]. CM I pediatric presentations from published series are reported in Table 1. These retrospective series include both operated and non operated CM I patients: 26 to 37% of the patients [4],[7] were asymptomatic with a fortuitous discovery, while the remaining had a variety of neurological symptoms including headaches, ataxia, sensory or motor deficits and lower cranial abnormalities. The most common symptoms were headaches and scoliosis [5].

Oropharyngeal dysfunction is not frequently reported. In fact, in Tubbs’study on 500 cases of pediatric CM I, oropharyngeal dysfunction only represented 4% of the symptoms [5]. In some studies involving over 100 patients no esophageal symptoms were reported [1],[4],[7]. Moreover, these dysfunctions are often poorly described, and can manifest with cough, stridor, dysphagia, abnormal vocal cord movement, GERD, aspiration, prolonged feeding, vomiting, sleep apnea or failure to thrive [3],[6]. Perkin et al. [8] have reported common dysphagia in patients with CM1 malformation by traction of the lower cranial nerves secondary to the herniation by the CM1 malformation. Dysphagia is associated with a global impairment of all phases of swallowing on videofluoroscopy. As they mention dysphagia may be the presenting symptom in some patients.

Cardi et al. [9] described gastroparesis as a cause of Sandifer syndrome. Indeed gastroparesis may enhance GERD and thus subsequently induce a Sandifer syndrome. Our patient had a very unusual presentation and we initially thought that he presented with an atypical case of Sandifer syndrome as he had well documented severe gastroparesis and GERD. We do not exclude that he might have had pre-existing asymptomatic gastroparesis. Deterioration of his CMI might have worsened his gastroparesis. We were unable to obtain invasive diagnostic procedures (as esophageal pH probe study) after the patient’s surgery but we did obtain a milk scan study a year after surgery which showed improved but persistent gastroparesis in an absolutely symptom free patient. Neurological and gastrointestinal symptoms are frequently associated in different neurological conditions.

Greenlee et al. reported abnormal movements in 6 children with CM I but did not describe them [3]. To our knowledge, no study has reported abnormal movements related to eating in association with CM I.

In conclusion, our patient’s presentation is clearly unique and the total resolution of symptoms following posterior fossa decompression surgery confirms the link between the abnormal postures and CM I. Again, we were unable to perform control studies following surgery due to the patient and the parents’ decision to not perform any further invasive testing.

In the literature, complications occur in only 2.4% of the patients undergoing decompressive surgery for CM I [5]. Spontaneous resolution of childhood CM I has been described in several cases [10]. The Benglis study represents the largest series of pediatric patients with CM I followed without surgery. No new neurological deficits were observed during the follow up period in this population [4], adding to the controversy regarding the indication for surgery [7]. Therefore, pediatric patients with CM I who are not clearly symptomatic and do not have a syrinx or scoliosis, should not undergo surgery [4].

Conclusion

Symptomatic CM I are being increasingly recognized in young children. The availability of MRI has certainly contributed to this phenomenon. As shown in our case, children may present with atypical manifestations, making CM I a complex clinical diagnostic challenge. CM I should be considered in the differential diagnosis of atypical oropharyngeal dysfunction.

Consent

Written informed consent was obtained from the patient’s parents and assent was obtained from the patient (as he was too young for a written consent) for publication of this case report and any accompanying images. A copy of the written consent is available for review by the Editor of this journal. The study was approved by the local institutional board.

Abbreviations

- CM 1:

-

Chiari I

- PPI:

-

Proton pump inhibitors

- ENT:

-

Ear, throat and nose

- MRI:

-

Magnetic resonance imaging

- GERD:

-

Gastroesophageal reflux disease

- GER:

-

Gastroesophageal reflux

References

Park JK, Gleason PL, Madsen JR, Goumnerova LC, Scott RM: Presentation and management of Chiari I malformation in children. Pediatr Neurosurg. 1997, 26 (4): 190-196. 10.1159/000121190.

Caldarelli M, Novegno F, Vassimi L, Romani R, Tamburrini G, Di Rocco C: The role of limited posterior fossa craniectomy in the surgical treatment of Chiari malformation type I: experience with a pediatric series. J Neurosurg (3 suppl pediatrics). 2007, 106 (3 suppl): 187-195. 10.3171/ped.2007.106.3.187.

Greenlee J, Donovan KA, Hasan DM, Menezes AH: Chiari I malformation in the very young child: the spectrum of presentations and experience in 31 children under age 6 years. Pediatrics. 2002, 110 (6): 1212-1219. 10.1542/peds.110.6.1212.

Benglis D, Covington D, Bhatia R, Elhammady MS, Ragheb J, Morrison G, Sandberg DI: Outcomes in pediatric patients with Chiari malformation type I followed up without surgery. J Neurosurg Pediatrics. 2011, 7 (4): 375-379. 10.3171/2011.1.PEDS10341.

Tubbs RS, Beckman J, Naftel RP, Chern JJ, Wellons JC, Rozzelle CJ, Blount JP, Oakes WJ: Institutional experience with 500 cases of surgically treated pediatric Chiari malformation type I. J Neurosurg Pediatrics. 2011, 7 (3): 248-256. 10.3171/2010.12.PEDS10379.

Albert GW, Menezes AH, Hansen DR, Greenlee JD, Weinstein SL: Chiari malformation type I in children younger than age 6 years: presentation and surgical outcome. J Neurosurg Pediatrics. 2010, 5 (6): 554-561. 10.3171/2010.3.PEDS09489.

Aitken LA, Lindan CE, Sidney S, Gupta N, Barkovich AJ, Sorel M, Wu YW: Chiari type I malformation in a pediatric population. Pediatr Neurol. 2009, 40 (6): 449-454. 10.1016/j.pediatrneurol.2009.01.003.

Perkin GD, Murray-Lyon I: Neurology and the gastrointestinal system. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1998, 65 (3): 291-300. 10.1136/jnnp.65.3.291.

Cardi E, Corrado G, Cavaliere M, Capocaccia P, Matrunola M, Rea P, Pacchiarotti C: Delayed gastric emptying in an infant with Sandifer syndrome. Ital J Gastroenterol. 1996, 28 (9): 518-519.

Sun PP, Harrop J, Sutton LN, Younkin D: Complete spontaneous resolution of childhood Chiari I malformation and associated syringomyelia. Pediatrics. 2001, 107: 182-184. 10.1542/peds.107.1.182.

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge the pediatric gastroenterology, hepatology and nutrition service of the CHU Sainte-Justine, Université de Montréal, Montréal, and the pediatric neurosurgery department of CHU Sainte-Justine. We also acknowledge Mrs Nicole Thériault for all her secretarial help and Mrs Hélène Restieri for her nursing support to the patient and his family.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

SB: Conducted a critical analysis of the case reviewed the literature and wrote the manuscript. LC: Revised the manuscript and added a critical review to the surgical part of the manuscript. CD: Conceived of the study, participated in its design and coordinated and helped to draft and edit the final manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Authors’ original submitted files for images

Below are the links to the authors’ original submitted files for images.

Rights and permissions

This article is published under an open access license. Please check the 'Copyright Information' section either on this page or in the PDF for details of this license and what re-use is permitted. If your intended use exceeds what is permitted by the license or if you are unable to locate the licence and re-use information, please contact the Rights and Permissions team.

About this article

Cite this article

Berthet, S., Crevier, L. & Deslandres, C. Abnormal movements associated with oropharyngeal dysfunction in a child with Chiari I malformation. BMC Pediatr 14, 1174 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12887-014-0294-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12887-014-0294-3