Abstract

Background

Gingival metastasis from primary hepatocellular cancer (HCC) is rare, highly malignant, and generally has no distinct symptoms. Not performing a biopsy can lead to misdiagnosis. This article reports an 87-year-old male with gingival metastasis from HCC. To gain a better insight into this disease, we also conducted a literature review of 30 cases and discussed the clinical and pathological characteristics, diagnosis, treatment and prognosis of this unusual form of liver cancer.

Case presentation

An 87-year-old man was hospitalized with a chief complaint of chronic constipation and diffuse lower extremity edema. His past medical history included a three-year hepatitis B infection and a cerebral infarction 17 years prior. Imaging examination detected a massive hepatocellular carcinoma in the right liver lobe and multiple metastases in the lungs. Oral examinations revealed a reddish, cherry-sized exophytic mass on the right upper gum. The mass was tentatively diagnosed as a primary gingival tumor and was ultimately confirmed by biopsy as a metastatic carcinoma originating in the liver. The patient decided, with his guardians, to receive palliative care and not to remove the mass. Unfortunately, the patient accidentally bit the mass open; profuse bleeding ensued and local pressure exerted a poor hemostatic effect. The patient’s condition worsened, and he eventually died of multiple organ failure. We also performed a literature review and discussed 30 cases of gingival metastases from HCC. The findings indicated that these lesions affected males more than females, with a ratio of 6:1, and infiltrated the upper gingivae (63.1%) more than the lower gingivae (36.7%). Survival analysis indicated that the overall survival for patients with upper gingival metastasis was worse than for those with lower gingival metastasis, and patients receiving treatments for primary liver cancer or metastatic gingival tumors had better overall or truncated survival times.

Conclusion

Gingival metastasis from primary hepatocellular carcinoma is rare, and its diagnosis has presented challenges to clinicians. To avoid a potential misdiagnosis, a biopsy is mandatory regardless of whether a primary cancer is located. Early diagnosis and treatment for primary liver cancer or metastatic gingival lesions may improve survival expectations.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) is prevalent worldwide, especially among the populations in East Asian countries [1]. Distant metastasis sites include the lungs, lymph nodes, bones, brain and gingivae [2]. Gingival metastasis from HCC has an especially high malignancy and poor prognosis, although it is traditionally regarded as a rare disease [3]. To the best of our knowledge, no more than 12 cases of gingival metastasis from HCC have been included in major literature sources, such as PubMed and Web of Science [4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16]. Nevertheless, these resources have not covered some of the relevant cases published in either English or non-English journals [3, 17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33]. In this manuscript, we reported a male patient aged 87 with gingival metastasis from HCC. Additionally, we performed a literature review of 30 cases to further discuss the clinical and pathological characteristics, diagnosis, treatments, and prognosis of gingival metastasis from HCC. This case series includes the present case and additional cases retrieved from journals published in East Asia, which has the world’s largest HCC population [1].

Case presentation

An 87-year-old male patient with a chief complaint of chronic constipation and diffuse lower extremity edema was referred to the gastroenterology department at Guangdong Provincial People’s Hospital. A review of the patient’s past medical history revealed chronic hepatitis B infection and liver cirrhosis for 3 years, as well as depressive-anxiety neurosis and sequelae of a cerebral infarction 70 years prior. Abdominal computerized tomography (CT) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scans revealed a well-defined low-density solid mass measuring approximately 15.0 × 13.0 cm in the right liver lobe surrounded by multiple nodules (Fig. 1a, b). Chest X-rays and CT scans detected multiple nodules in both lungs (Fig. 1c, d). The patient was clinically diagnosed with advanced primary liver cancer and multiple intrahepatic and lung metastases. Laboratory tests revealed anemia (hemoglobin 83 g/L), hypoproteinemia (albumin 27.7 g/L), hyponatremia (Na+ 125.8 mmol/L), and hyperammonemia (ammonia 65.0 µmol/L). Elevated serum levels of creatine (Cr, 105.1 µmol/L), total bilirubin (TBIL, 25.3 µmol/L), and gamma-glutamyl transpeptidase (GGT, 379 U/L), as well as impaired blood clotting function [International normalized ratio (INR), 1.22; activated partial thromboplastin time (APTT), 46.8 s] were reported. A significantly elevated level of carbohydrate antigen-125 (CA-125, 163.8 U/L) was also disclosed; however, the serum level of alpha-fetoprotein (AFP) was within the normal range.

Oral examinations discovered a reddish soft tissue swelling measuring 2.5 × 2.5 × 2.0 cm with a well-defined border on the gingiva adjacent to the lower left mandible. The mass was bleeding slightly. The mass was provisionally diagnosed as a primary gingival tumor. Considering his poor organ function that prohibited active treatment, such as partial hepatectomy or chemoembolization, the patient decided, with his guardians, to receive palliative treatment for the primary liver cancer. Regarding the treatment for the gingival mass, a stomatologist was consulted; his advice was that the tumor could be resected to relieve any trouble with chewing or eating resulting from the existence of the mass as an oral obstacle. Considering the patient’s poor condition, however, the patient and his guardians decided that he would receive palliative treatment. One episode of profuse bleeding from the root of the gingival lesion occurred and was staunched by local compression. The disease remained relatively stable until considerable progression was observed approximately 1 month after the patient was discharged from the hospital. When the patient was once again admitted to our hospital 2 months later, the mass size had rapidly doubled to 5 × 5 × 4 cm (Fig. 2). Obstructed by the lump, the patient was only able to receive a fluid diet. Unfortunately, with progressed unconsciousness from the sequelae of cerebral infarction, the patient bit the mass open by chance, and profuse bleeding occurred at the residual lesion. Despite pressing continuously to staunch the bleeding and transfusing blood to improve subsequent anemia, the patient’s condition worsened, and he eventually died of multiple organ failure 2 days later.

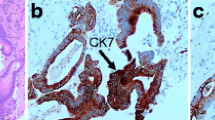

A tissue biopsy from the gingival mass was performed. Histologic examination revealed a squamous epithelium-coated neoplasm dotted with cells that had grown in an invasive trabecular pattern surrounded by a sinusoid network. Largely resembling hepatocytes, the tumor cells with abundant cytoplasm displayed moderate nuclear atypia with some nuclei discernible (Fig. 3). This microscopic appearance was compatible with the diagnosis of HCC. Immunohistochemistry (IHC) tests demonstrated that the tissue showed strong positive reactions to antibodies against hepatocytes (Fig. 4a), CAM5.2 (Fig. 4b), and CD10 (Fig. 4c) and low affinity to antibodies against glypican-3, arginase-1, thyroid transcription factor-1, and cytokeratin-7. Ultimately, the gingival mass was definitively diagnosed as a metastasis from HCC.

Literature review

Literature

Any searchable literature in the PubMed, Web of Science and Google Scholar databases concerning gingival metastasis from HCC, whatever language it was published in, is included. The search term used was “cancer” OR “carcinoma” OR “tumor” OR “neoplas*”) AND (“liver” OR “hepatic” OR “hepatocellular”) AND “metasta*” AND “gingiv*”. The references attached to all searched articles serve as a secondary source. A total of 30 cases, including the present case, were reported from 1964 to 2019 and were collected for analysis, including 26 English and four non-English case reports. Twenty-two cases were reported in the twenty-first century. Available data regarding clinical and pathological characteristics are summarized in Tables 1 and 2.

Age and sex

The disease occurred among people between the ages of 43 and 87, with a median age of 60. Most cases were male with a male-to-female ratio greater than 6:1 (26:4) (Table 3).

Preexisting hepatopathy

Twelve cases had a history of posthepatic cirrhosis; seven developed from chronic hepatitis B infection and five developed from chronic hepatitis C infection. In addition, three cases were diagnosed with alcoholic cirrhosis, and one case was diagnosed with transfusion hepatitis cirrhosis. For the remaining cases, five were reportedly free of hepatopathy, and nine lacked a description of a previous history of liver disease (Table 3).

Gingival metastatic site manifestation

Twelve (40.0%) cases presented with no primary HCC symptoms; their first manifestation was gingival lesions. The distributions of the metastatic lesions on the gingivae are summarized in Table 3. Regarding the location on the gingiva, the lesion presented with a preference for the upper (19, 63.3%) compared to the lower gingiva (11, 36.7%) but no preference for the left, central, or right gingiva. Bleeding and rapid growth were the most common manifestations (Table 3).

Pathological differentiation grade

The tumor differentiation grade was evaluated in compliance with the World Health Organization Classification of Tumors by the International Agency for Research on Cancer. One case was excluded due to its lack of description. Among the remaining 29 cases, 19 (63.3%), 5 (16.7%), 2 (6.7%), and 3 (10.0%) cases were assessed as moderate, poor, high differentiation, and undifferentiated, respectively. (Table 3).

Metastasis to sites other than the gingiva

In addition to the gingiva, the most frequent metastatic site was the lungs, followed by the lymph nodes, brain, adrenal glands and others, in descending order by frequency (Table 3).

Survival analysis

Data regarding overall survival and truncated survival were analyzed. Overall or truncated survival was defined as the period from the onset of HCC or gingival metastasis to death, respectively. Six cases with incomplete data were discarded. The remaining twenty-four cases were included in the survival analysis using SAS software (SAS v9.4; SAS Institute, NC, USA). Survival analysis indicated that gingival lesions as the first sign of HCC (P = 0.0008, Fig. 5a) and located on the upper gingiva (P = 0.0211, Fig. 5b) presented worse overall survival. Treating the primary HCC improved overall survival (P = 0.0019, Fig. 5c), while treating the metastatic gingival tumor improved truncated survival (P = 0.0482, Fig. 5d).

Kaplane-Meier curves for primary hepatocellular carcinoma with metastasis to the gingiva. The curves illustrate (a) the overall survival according to gingival metastatic tumor as the first sign, (b) the overall survival according to metastasis to upper gingiva, (c) the overall survival according to treatments for primary hepatocellular carcinoma, and (d) the truncated survival according to treatments for gingival metastatic tumor

Discussion and conclusions

According to a large-scale global investigation of cancers [1], hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) ranked sixth in cancer incidence and fourth in cancer mortality worldwide. Despite significant mortality reductions in East Asian countries, such as China, Korea, and Japan, HCC remains the third most common and fatal cancer. Over 50% of HCC patients had extrahepatic metastases, most frequently affecting the lungs, skeleton, brain, abdominal lymph nodes [34]. Metastasis of HCC to the gingiva was believed to be extremely uncommon. However, the rarity of gingival metastasis may be overestimated; some cases published in either English [3, 17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33] or non-English [21, 31] journals were not covered by the major literature databases. Some cases may not be reported at all due to potential misdiagnosis. Some cases first manifested as only gingival lesions [21, 24, 25, 27, 28, 33] or mimicked benign gingival disease [14, 22], both of which would lead to misdiagnosis, especially in the absence of a biopsy and pathological examination.

Gingival metastasis can originate from a wide range of primary sites, including lung, breast, kidney, bone, colorectal, adrenal, and liver [35]. The possible pathophysiological mechanism of HCC metastasis to the gingiva remains to be elucidated. The hematogenous route by invasion of the hepatic arterial or portal venous branches is believed to be the preferred mode for oral metastasis [36,37,38], although, in some cases, metastatic pulmonary tumors are absent [1, 7, 9,10,11, 13,14,15, 19, 20, 22, 23, 28, 32, 33]. Among those cases, the valveless vertebral venous plexus (Batson’s plexus) has been proposed as a mechanism for bypassing filtration through the pulmonary, inferior caval and portal venous circulations [39, 40]. This pathway may be the most likely pathway responsible for HCC metastasis to the gingiva without pulmonary metastasis. In addition to the Batson’s plexus, the other possible routes of gingival metastasis include arterial, venous, and lymphatic circulations [6]. In light of the fact that liver cirrhosis presents in over 50% of HCC patients with metastatic gingival tumors, we cautiously propose a hypothesis that the altered hemodynamics subsequent to esophageal varices may be one of potential pathways for oral metastases, particularly in HCC patients with liver cirrhosis with incomplete compensation.

So far, at least 30 cases of gingival metastasis from HCC have been retrieved from the existing literature sources. Analyzing these cases can help us gain new insights into the clinical and pathological characteristics of gingival metastasis in HCC. First, our present analysis demonstrates a remarkable sex preference in the occurrence of gingival metastasis from HCC. The ratio of male to female is greater than 6:1 (26/4), which far outweighs the overall male-to-female ratio of approximately 3:1 in liver cancer incidence [1]. These inconsistencies raise questions as to whether the relatively poorer general health habits or oral health behaviors among males, such as smoking and drinking, as revealed in a study [41], may favor the pathogenesis of gingival metastasis from HCC. Pathogenesis of this special metastasis is thought to be associated with oral inflammation, such as gingivitis, that possibly attracts migration and adhesion of cancer cells to the gingiva [38]. Chronic inflammation has been involved in various steps of tumorigenesis, including cellular transformation, survival, proliferation, invasion, angiogenesis, and metastasis [42, 43]. The rich capillary network of the chronically inflamed gingiva and the presence of some inflammatory molecules may favor the progression of metastatic cells [38]. Future investigation of this possible mechanism remains to be conducted.

Moreover, according to our survival analysis, patients with a gingival mass as the first sign of HCC had extremely poor survival. The concurrent multiple extrahepatic metastases may have contributed to this poor survival observation. However, among those HCC cases with gingival lesions as the first sign, distant metastasis outside the gingiva was not reported in three cases [10, 24, 28]. In this scenario, the delayed diagnosis and treatment, to some extent resulting from the absence of indications of underlying liver cancer, may worsen survival. This further raises the importance of early diagnosis and treatment of a potential gingival metastasis from HCC or other distant tumors. A timely biopsy is necessary for any neoplasm, even if it resembles a benign lesion [9, 14].

In addition, HCC is more likely to spread to the upper gingiva than the lower gingiva. Looking into the anatomy, we find several structural factors for this distribution preference. The anatomical characteristics of the arteries supplying blood to the gingivae may contribute to the difference. The upper gingiva accepts blood through two main arteries, namely, the superior dental artery and the infraorbital artery. The two arteries, as direct extensions of their stem artery (maxillary artery), have wider diameters and larger blood volumes [44]. Meanwhile, the lower gingiva only accepts blood through one smaller artery called the inferior dental artery, which is a thinner branch of the stem artery. The increase in blood flow may increase the risk of implantation by circulating tumor cells for the upper gingiva.

Early diagnosis of a metastasized gingival mass from underlying primary cancer was critical to the patients’ prognosis. However, misdiagnosis or a missed diagnosis could arise from several factors. First, the low incidence rate and indistinctive manifestation (bleeding, swelling, ulceration, etc.) posed fresh challenges to physicians in acknowledging this rare disease. Second, the deceiving characteristics of the gingival lesions, for instance, mimicking a pyogenic granuloma [14, 22], would make physicians overlook the necessity of a biopsy. However, a gingival mass’s characteristic of rapid growth can put physicians on high alert for a malignancy. As reported in the present case, the gingival lesion was first diagnosed as a primary gingival tumor until the biopsy and the pathological test were completed; then, a metastasis from HCC was finally identified.

The main treatments of primary hepatocellular carcinoma involved hepatectomy, chemotherapy, transarterial chemoembolization (TACE), transcatheter arterial embolization (TAE), novel targeted therapy (sorafenib), and combination therapy. The major treatments for the gingiva lesions included resection, chemotherapy, radiotherapy, and TAE. Survival analysis demonstrated that patients receiving treatments for primary cancer or metastatic gingival lesions appeared to have better overall survival or truncated survival. However, there may be biases between the treated and untreated patient groups. For example, about 20% of the previous case reports lack survival information, and the untreated population may have had a poorer performance status, like our present case. The treatment effectiveness for survival remains to be confirmed based on large sample randomized controlled studies.

As an integral part of evidence-based medicine, case reports and literature reviews have profoundly influenced the medical literature, and they continue to advance our knowledge of diseases and help generate hypotheses to conduct clinical studies and basic research. Despite the relatively small sample size, this case report and literature review may be valuable for physicians to update their knowledge for their daily practice. Enhanced recognition, early diagnosis, and appropriate management of gingival metastasis may help improve the overall outcomes for this distinct subgroup of HCC. Further retrospective or prospective studies with a larger sample size of patients are still required.

Gingival metastasis from primary liver cancer is rare, and the diagnosis of a gingival metastatic lesion is challenging to clinicians. To avoid potential misdiagnosis, a biopsy is mandatory, even if no distinct clinical presentation is observed. Early diagnosis and treatments for primary liver cancer or metastatic gingival lesion may improve survival expectations.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- AFP:

-

Alpha-fetoprotein

- APTT:

-

Activated partial thromboplastin time

- CA-125:

-

Carbohydrate antigen-125

- CT:

-

Computed tomography

- GGT:

-

Gamma-glutamyl transpeptidase

- HCC:

-

Hepatocellular carcinoma

- IHC:

-

Immunohistochemistry

- INR:

-

International normalized ratio

- MRI:

-

Magnetic resonance imaging

- TACE:

-

Transarterial chemoembolization

- TAE:

-

Transcatheter arterial embolization

- TBIL:

-

Total bilirubin

References

Fitzmaurice C, Allen C, Barber RM, Barregard L, Bhutta ZA, Brenner H, Dicker DJ, Chimed-Orchir O, Dandona R, Dandona L, et al. Global, regional, and National Cancer Incidence, mortality, years of life lost, years lived with disability, and disability-adjusted life-years for 32 Cancer groups, 1990 to 2015: a systematic analysis for the global burden of disease study. JAMA oncology. 2017;3(4):524–48.

Wu W, He X, Andayani D, Yang L, Ye J, Li Y, Chen Y, Li L. Pattern of distant extrahepatic metastases in primary liver cancer: a SEER based study. J Cancer. 2017;8(12):2312–8.

Pires FR, Sagarra R, Correa ME, Pereira CM, Vargas PA, Lopes MA. Oral metastasis of a hepatocellular carcinoma. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2004;97(3):359–68.

Lapeyrolerie FM, Manhold JH Jr. Hepatoma metastatic to the gingiva; report of a case. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1964;18:365–7.

Radden BF, Reade PC. Gingival metastasis from a hepatoma. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1966;21(5):621–5.

Lund BA, Soule EH, Moertel CG. Hepatocellular carcinoma with metastasis to gingival mucosa: report of case. J Oral Surg. 1970;28(8):604–7.

Wedgwood D, Rusen D, Balk S. Gingival metastasis from primary hepatocellular carcinoma. Report of a case. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1979;47(3):263–6.

Morishita M, Fukuda J. Hepatocellular carcinoma metastatic to the maxillary incisal gingiva. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1984;42(12):812–5.

Kanazawa H, Sato K. Gingival metastasis from primary hepatocellular carcinoma: report of a case and review of literature. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1989;47(9):987–90.

Llanes F, Sanz-Ortega J, Suarez B, Sanz-Esponera J. Hepatocellular carcinomas diagnosed following metastasis to the oral cavity. Report of 2 cases. J Periodontol. 1996;67(7):717–9.

English JC 3rd, Meyer C, Lewey SM, Zinn CJ. Gingival lesions and nasal obstruction in an immunosuppressed patient post-liver transplantation. Cutis. 2000;65(2):107–9.

Maiorano E, Piattelli A, Favia G. Hepatocellular carcinoma metastatic to the oral mucosa: report of a case with multiple gingival localizations. J Periodontol. 2000;71(4):641–5.

Papa F, Ferrara S, Felicetta L, Lavorgna G, Matarazzo M, Staibano S, De Rosa G, Troisi S, Claudio PP. Mandibular metastatic hepatocellular carcinoma: report of a case involving severe and uncontrollable hemorrhage. Anticancer Res. 2001;21(3C):2121–30.

Ramon Ramirez J, Seoane J, Montero J, Esparza Gomez GC, Cerero R. Isolated gingival metastasis from hepatocellular carcinoma mimicking a pyogenic granuloma. J Clin Periodontol. 2003;30(10):926–9.

Arai R, Otsuka T, Mori K, Kobayashi R, Tomizawa Y, Sohara N, Kakizaki S, Hirokawa T, Kanda D, Nakayama H, et al. Metastasis of hepatocellular carcinoma to the supramaxillary gingiva and right ventricle. Hepatogastroenterology. 2004;51(58):1159–61.

Xue LJ, Mao XB, Geng J, Chen YN, Wang Q, Chu XY. Rare gingival metastasis by hepatocellular carcinoma. Case Rep Med. 2017;2017. https://doi.org/10.1155/2017/3192649.

Yoshida Y, Tsukuda T, Yoshinari M, Sasaki H. Two cases of metastatic tumors to the mouth (author's transl). Nihon Koku Geka Gakkai Zasshi. 1976;22(4):534–40.

Tokuyama K, Koike S, Takashima S, Moriwaki S, Uyama K. Jinno K: [a case report of pedunculated hepatoma with very rare remote metastases after the resection]. Gan No Rinsho. 1984;30(2):174–80.

Kuga Y, Kitamura A, Kusaba I, Aketa J, Yamada N. Primary liver cancer with metastasis to the gingiva: report of a case (author's transl). Nihon Koku Geka Gakkai Zasshi. 1976;22(4):541–5.

Choi SJ, Kim YS, Kim NR, Jeong SW, Lee SH, Jeong JS, Ryu KH, Cha SW, Hong SJ, Ryu CB, et al. A case of hepatocellular carcinoma with metastasis to gingival mucosa. Taehan Kan Hakhoe Chi. 2002;8(4):495–9.

Kuo I-J, Chen P-R, Hsu Y-H. Gingival Metastasis of Primary Hepatocellular Carcinoma - Case report. Tzu Chi Med J. 2003;18:145–7.

Rim JH, Moon SE, Chang MS, Kim JA. Metastatic hepatocellular carcinoma of gingiva mimicking pyogenic granuloma. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2003;49(2):342–3.

Elkhoury J, Cacchillo DA, Tatakis DN, Kalmar JR, Allen CM, Sedghizadeh PP. Undifferentiated malignant neoplasm involving the interdental gingiva: a case report. J Periodontol. 2004;75(9):1295–9.

Rai S, Naik R, Pai MR, Gupta A. Metastatic hepatocellular carcinoma presenting as a gingival mass. Indian J Pathol Microbiol. 2009;52(3):446–7.

Huang YC, Tung CL, Lin HC. Gingival tumor as the first sign of advanced hepatocellular carcinoma on FDG PET/CT. Clin Nucl Med. 2009;34(2):72–3.

Inaba H, Kanazawa N, Wada I, Yoneyama K, Fujii T, Hoshino T, Watanabe H, Komatsu M, Fujishima Y, Takikawa Y, et al. A case of hepatocellular carcinoma with bleeding gingival metastasis treated by transcatheter arterial embolization. Nihon Shokakibyo Gakkai Zasshi. 2011;108(1):95–102.

Poojary D, Baliga M, Shenoy N, Amirthraj A, Kumar R. Adrenal insufficiency with gingival mass--an unusual presentation of hepatocellular carcinoma. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2011;69(7):e291–3.

Terada T. Hepatocellular carcinoma metastatic to the gingiva as a first manifestation of hepatocellular carcinoma. J Maxillofac Oral Surg. 2011;10(3):271–4.

Greenstein A, Witherspoon R, Iqbal F, Coleman H. Hepatocellular carcinoma metastasis to the maxilla: a rare case. Aust Dent J. 2013;58(3):373–5.

Gentile NM, McKenzie KM, Hurt RT. Two rare forms of hepatocellular carcinoma metastases. BMJ Case Rep. 2013;2013. https://doi.org/10.1136/bcr-2013-008886.

Chen H-M, Wu Y-C, Wei L-Y, Chiang C-P. Metastatic hepatocellular carcinoma of the anterior palatal gingiva. Journal of Dental Sciences. 2014;9:202–4.

Gong LI, Zhang WD, Mu XR, Han XJ, Yao LI, Zhu SJ, Zhang FQ, Li YH, Zhang W. Hepatocellular carcinoma metastasis to the gingival soft tissues: a case report and review of the literature. Oncol Lett. 2015;10(3):1565–8.

Kwon MJ, Ryu SH, Jo SY, Kwak CH, Yoon WJ, Moon JS, Lee HK. A case of hepatocellular carcinoma presenting as a gingival mass. Korean J Gastroenterol. 2016;68(6):321–5.

Anthony PP. Hepatocellular carcinoma: an overview. Histopathology. 2001;39(2):109–18.

Hirshberg A, Shnaiderman-Shapiro A, Kaplan I, Berger R. Metastatic tumours to the oral cavity - pathogenesis and analysis of 673 cases. Oral Oncol. 2008;44(8):743–52.

Zubler MA, Rivera R, Lane M. Hepatoma presenting as a retro-orbital metastasis. Cancer. 1981;48(8):1883–5.

Fujihara H, Chikazu D, Saijo H, Suenaga H, Mori Y, Iino M, Hamada Y, Takato T. Metastasis of hepatocellular carcinoma into the mandible with radiographic findings mimicking a radicular cyst: a case report. J Endod. 2010;36(9):1593–6.

Hirshberg A, Leibovich P, Buchner A. Metastases to the oral mucosa: analysis of 157 cases. J Oral Pathol Med. 1993;22(9):385–90.

Batson OV. The function of the vertebral veins and their role in the spread of metastases. Ann Surg. 1940;112(1):138–49.

Batson OV. The vertebral system of veins as a means for cancer dissemination. Prog Clin Cancer. 1967;3:1–18.

Fukai K, Takaesu Y, Maki Y. Gender differences in oral health behavior and general health habits in an adult population. Bull Tokyo Dent Coll. 1999;40(4):187–93.

Aggarwal BB, Shishodia S, Sandur SK, Pandey MK, Sethi G. Inflammation and cancer: how hot is the link? Biochem Pharmacol. 2006;72(11):1605–21.

Mantovani A. Cancer: inflammation by remote control. Nature. 2005;435(7043):752–3.

Gleeson M, editor. Facial branches of the maxillary artery. In: Gray's Anatomy - The Anatomical Basis of Clinical Practice. 41st ed. London: Elsevier; 2016. p. 499.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

Lishu Xu is currently receiving a grant (#2018YFC2000300) from National Key R&D Program of China. Yating Hou is currently receiving a grant (#K18010402), and Linhui Hu is currently receiving a grant (#K17010402), both from the Guangdong Provincial People’s Hospital Scientific Research Start-up Fund for Graduates. The funding sources played no role in the design of the study and collection, analysis, and interpretation of data and in writing the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

YTH, GD, WPD, and LSX contributed the conception and design of the study. YTH was a major contributor in writing the manuscript. LHH analyzed and interpreted the patient data regarding the disease. CL performed the histological examination of the gingival mass. All authors drafted the article and revised it critically for important intellectual content, and approved the final manuscript to be submitted.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The ethics committee of the Guangdong Provincial People’s Hospital approved this study. The son of the patient agreed to participate in the study with all relevant data. And written informed consent was obtained from the son of the patient.

Consent for publication

Written informed consent for publication of the clinical details and clinical images was obtained from the son of the patient.

Competing interests

All authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Hou, Y., Deng, W., Deng, G. et al. Gingival metastasis from primary hepatocellular carcinoma: a case report and literature review of 30 cases. BMC Cancer 19, 925 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12885-019-6020-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12885-019-6020-7