Abstract

Objective

Crizotinib can target against mesenchymal-epithelial transition (MET) and anaplastic lymphoma kinase (ALK), which has been considered as a multi-targeted tyrosine kinase inhibitor (TKI). The objective of this study was to explore the efficacy of crizotinib in advanced non-small-cell lung cancer (NSCLC) with concomitant ALK rearrangement and c-Met overexpression.

Methods

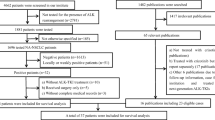

Totally, 4622 advanced NSCLC patients from two institutes (3762 patients at the Guangdong Lung Cancer Institute from January 2011 to December 2016 and 860 cases at the Perking Cancer Hospital from January 2015 to December 2016) were screened for ALK rearrangement with any method of IHC, RACE-coupled PCR or FISH. C-Met expression was performed by IHC in ALK-rearranged patients, and more than 50% of cells with high staining were defined as c-Met overexpression. The efficacy of crizotinib was explored in the ALK-rearranged patients with or without c-Met overexpression.

Results

Sixteen patients were identified with c-Met overexpression in 160 ALK-rearranged cases, with the incidence of 10.0% (16/160). A total of 116 ALK-rearranged patients received the treatment of crizotinib. Objective response rate (ORR) was 86.7% (13/15) in ALK-rearranged patients with c-Met overexpression and 59.4% (60/101)in those without c-Met overexpression, P = 0.041. Median PFS showed a trend of superiority in c-Met overexpression group (15.2 versus 11.0 months, P = 0.263). Median overall survival (OS) showed a significant difference for ALK-rearranged patients with c-Met overexpression group of 33.5 months with the hazard ratio (HR) of 3.2.

Conclusions

C-Met overexpression co-exists with ALK rearrangement in a small population of advanced NSCLC. There may be a trend of favorable efficacy of crizotinib in such co-altered patients.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Targeted therapy has led to a therapeutic paradigm shift in lung cancer, which brought the treatment of lung cancer into the era of precision medicine [1]. At least one genetic abnormality has been detected in 64% patients with lung adenocarcinoma. The rearrangement between echinoderm microtubule-associated protein like 4 (EML4) and anaplastic lymphoma kinase (ALK) resulted in the activation of ALK kinase, which was identified as a driver oncogene in non-small-cell lung cancer (NSCLC) in 2007 [2]. Although ALK fusion accounted for only 3 to 13% patients with advanced NSCLC, it has made significant effect on the treatment of advanced NSCLC as precise targeted treatment [2,3,4]. ALK rearrangement can be identified with fluorescent in situ hybridization (FISH), rapid amplification of cDNA ends coupled polymerase chain reaction (RACE-coupled PCR) and Ventana immunohistochemistry (IHC). In China, all the three methods were recommended by Chinese expert consensus and have been approved as companion diagnostic tests by the Chinese Food and Drug Administration [5].

Moreover, cellular-mesenchymal-epithelial transition (c-Met) has recently been discovered as a novel promising target in NSCLC [6]. The c-Met gene encodes a high-affinity receptor for hepatocyte growth factor (HGF) [7,8,9,10]. HGF binding augments the intrinsic tyrosine kinase activity of c-Met, resulted in wide range of biological activities, including cellular proliferation, motility, invasion, antiapoptotic responses, and dissemination [9]. The activation of c-Met pathway results from gain-of-function MET mutations, MET amplification and c-Met overexpression in many solid and hematological malignancies [11, 12]. MET amplification occurred in 7.3–10.4% of patients with untreated NSCLC [13,14,15]. MET exon 14-alteration accounted for 0.9–3.0% of lung adenocarcinoma, while c-Met protein was reportedly overexpressed in about 22.2–67.2% of NSCLC and associated with poor prognosis [16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23]. Since MET amplification is rare and difficulty in the detecting method of FISH, MET IHC acts as the most robust predictor of overall survival and progression-free survival to all examined exploratory markers [24]. C-Met overexpression was evaluated by IHC and a four-tier (0–3) intensity scoring system has been widely used in researches. However, a standard cutoff for c-Met overexpression has not been established yet. Patients with Met positivity of ≥50% of cells with moderate or strong staining were considered as the inclusion criteria of some clinical trials, such as MetMab clinical trials [23, 25,26,27], while patients with c-Met of ≥50% of cells with strong staining as the inclusion criteria of other trials [27, 28]. The activation of c-Met pathway has considered as one of the resistance mechanisms to EGFR-TKIs [29]. However, it is not clear that the role of c-Met overexpression plays in ALK-rearranged patients.

ALK rearrangements have previously been considered mutually exclusive with epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) and kirsten rat sarcoma viral oncogene homolog (KRAS) mutations [30,31,32]. However, approximately 0.3 to 1.3% of advanced patients harboring concomitant EML4-ALK rearrangements and EGFR mutations have been identified [33,34,35]. Similarly, overlap between ALK rearrangement and c-Met overexpression can also occur [20, 36]. Crizotinib, a multi-targeted TKI with activity against c-Met and ALK, has been considered as the first-line treatment for ALK-rearranged advanced NSCLC patients with remarkable response in a series of clinical trials [37,38,39,40] .The objective response rate (ORR) and median progression free survival (PFS) of crizotinib were 74% and 10.9 months in ALK-rearranged patients, compared with 45% and 7.0 months of chemotherapy respectively [39].

Of 19 patients with c-Met overexpression treated with crizotinib, 11 achieved partial response (PR) [41]. However, few data was available about the clinical activity of crizotinib for patients with ALK rearrangement and c-Met overexpression (ALK/c-Met) co-existence [36, 42]. Thus, our study was retrospectively conducted to investigate the frequency of ALK-rearrangement co-existing with c-Met overexpression in advanced NSCLC, as well as the efficacy of crizotinib for such co-altered patients.

Methods

Patients

This retrospective study was conducted on 4622 advanced patients from two institutes, including a cohort of 3762 patients with NSCLC at the Guangdong Lung Cancer Institute, the Guangdong General Hospital from January 2011 to December 2016 and a total of 860 at Peking University Cancer Hospital from January 2015 to December 2016. The inclusion criteria were: (1) pathologically confirmed advanced NSCLC with at least one measurable lesion; (2) identified with ALK rearrangement with any of these 3 methods: FISH, RACE-coupled PCR and Ventana IHC; (3) sufficient tissue for the analysis of c-Met IHC. Patients’ clinical and treatment information were extracted from electronic medical records at the Guangdong Lung Cancer Institute and the Peking University Cancer Hospital. Tumor histology was assessed by pathologists and staging was classified based on American Joint Committee on Cancer 7th edition of tumor, node, metastasis staging criteria [43]. This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the Guangdong General Hospital and all patients provided written informed consents.

Study design

In the present study, 160 ALK-rearranged patients were enrolled for the analysis of c-Met expression (Fig. 1). A total of 116 ALK-rearranged patients were treated with crizotinib. According to the results of c-Met overexpression, we divided this cohort into 2 groups: patients with c-Met overexpression and without c-Met overexpression. Objective responses were evaluated every 6 to 8 weeks according to Response Evaluation Criteria In Solid Tumors (RECIST) [44]. PFS was defined as time between the start of the treatment of crizotinib and disease progression or death. OS was measured as the period from the date of diagnosis to death resulting from any cause or censored at the last follow-up date. The last follow-up date was on October 30, 2017.

ALK rearrangement analyses

All tissue samples were routinely assessed with sectioning, hematoxylin and eosin staining, and visualization with a microscope to ensure tumor content was at least 50%. IHC was carried out on 4-mm thick slides using Ventana anti-ALK (D5F3) rabbit monoclonal primary antibody (Roche Diagnostics, Mannheim, Germany) according to the manufacturers’ instructions. ALK FISH analysis was performed on formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded tissues using a commercially available ALK probe (Vysis LSI ALK Dual Color, Break Apart Rearrangement Probe; Abbott Molecular, Abbott Park, IL) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Patients were diagnosed with ALK FISH-positive when 15% or more of scored tumor cells had split ALK 5′ and 3′ probe signals or had isolated 3′ signals. Total RNA was extracted from tissue samples with the RNeasy Kit (Qiagen). Reverse-transcriptase PCR and 5′ rapid ampli6fication c-DNA ends coupled PCR plus sequencing was performed out as ever reported [33]. PCR products were sequenced using a 3730XL Genetic Analyzer (Applied Biosystems). Target sequences were aligned with the ALK reference sequence (NM_004304.3) to determine if a novel fusion was present.

Detection of c-Met overexpression and MET amplification

C-Met protein expression was evaluated by IHC. Sections of 4 μm thick were cut from paraffin tissue blocks of NSCLC tumors. Staining was performed on a Ventana Benchmark XT automated immunostainer (Ventana) with a CONFIRM anti-total c-Met rabbit monoclonal primary antibody (SP44, Ventana Medical Systems, Tucson, AZ, USA) and an ultra View Universal DAB. A standard protocol for immunostaining of samples was used. A four-tier (0–3) intensity scoring system has been used in our present study, as shown in Fig. 2. More than 50% of cells with high staining were considered as c-Met overexpression. MET amplification was detected with the method of FISH. Dual-color FISH was performed in deparaffinized sections 4 μm thick using a c-Met/CEN7q Dual Color FISH Probe (Vysis, Abbott Laboratories). After the immersion of tissue sections and TRIS-EDTA (pH = 8.0), sections were washed in PBS. Then they were digested in a protease solution at 37 °C for 7–8 min and washed in PBS once more. The sections were co-denatured with probe at 80 °C for 5 min and then hybridized at 37 °C for 14–18 h and subsequently counterstained with DAPI. The results of positivity were assessed according to the 2 criteria: A c-Met: centromere 7 ratio ≥ 2.0 and the criterion of Cappuzzi (positivity: a mean of ≥5 copies per cell, or clustered gene amplification evident in all nuclei) [45].

EGFR and KRAS mutation analysis

Genomic DNA from each sample was used for sequence analysis of EGFR exons 18 to 21 and KRAS exons 2 and 3. These exons were amplified by PCR as previously described [46], and the resulting PCR products were purified and labeled for sequencing using the BigDye 3.1 Kit (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA) according to the manufacturer’s protocol.

Statistical analyses

Categorical variables were compared using X2 test, or Fisher exact test when necessary. Survival curves were constructed with the Kaplan–Meier method and differences analyzed by the log-rank test. Multivariable predictors were assessed by a forward step-wise likelihood ratio Cox proportional hazards model. Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS version 22.0 software (IBM, Armonk, NY). All statistical tests were two-sided, with P value < 0.05 considered statistically significant.

Results

Patients characteristics

A total of 4622 advanced NSCLC patients from two institutes (3762 patients at Guangdong Lung Cancer Institute from 2011 to 2016 and 860 cases at Perking Cancer Hospital from 2015 to 2016) with complete electronic records were screened for ALK gene status, of whom 282 were identified with ALK rearrangement. The study recruited 160 ALK-positive advanced NSCLC patients with sufficient tissue for the detection of c-Met expression. Sixteen patients were identified with c-Met overexpression, accounted for 10.0% (16/160) of ALK-rearranged patients. A total of 116 patients treated with crizotinib were investigated for the response to crizotinib. Baseline characteristics are presented in Table 1. The characteristics of ALK-rearranged patients with c-Met overexpression were relatively young with less than 45 years old, and most of them were female and non-smokers with adenocarcinoma. The baseline clinicopathologic characteristics were well balanced between ALK-rearranged patients with c-Met overexpression and those without c-Met overexpression. MET amplification was identified as negative by FISH in 8 ALK-rearranged NSCLC patients with c-Met overexpression, while 7 patients were unknown due to insufficient tissue (Table 2).

Response to crizotinib in ALK-rearranged NSCLC patients with c-Met overexpression

A total of 116 ALK-rearranged patients were enrolled in our study to assess the efficacy of crizotinib, including 101 patients without c-Met overexpression and 15 cases with c-Met overexpression. Objective response rate (ORR) was 86.7% (13/15) and 59.4% (60/101) in patients with and without c-Met overexpression groups, respectively. (P = 0.041) (Table 3). The waterfall plots for the best percentage change in target lesion size were shown for these two groups (Fig. 3a, b).

a, b Waterfall plots of the best percentage change of crizotinib in target lesions at baseline in ALK-positive patients with (b) or without c-Met overexpression (a). c PFS of crizotinib in ALK-positive patients with or without c-Met overexpression; d OS of ALK-positive patients with or without c-Met overexpression

Survival in ALK-rearranged NSCLC patients with c-Met overexpression

Median PFS showed a trend of superiority in c-Met overexpression group (15.2 versus 11.0 months, P = 0.263) (Fig. 3c). The median OS was 33.5 months (95%CI, 24.8–41.1 months) in ALK-rearranged patients without c-Met overexpression and not estimable in those with c-Met overexpression. (HR = 3.2, 95%CI, 1.06–4.67, P = 0.031) (Fig. 3b). The hazard ratio for death was 3.2 (95% CI, 1.06 to 4.67). Clinical variables including gender, smoking history, pathological type, ECOG status, clinical disease stage at diagnosis were analyzed using the multivariate Cox regression model, and results indicated that ECOG status (HR = 2.6; 95% CI = 1.29–5.41, P = 0.008) were independent prognostic factors of OS.

Discussion

The study of two institutes demonstrated that ALK-rearranged patients with c-Met overexpression that received crizotinib experienced a significant ORR, median OS and a trend of superiority of median PFS, compared with those without overexpression. It is the first study showing the clinical improvement of crizotinib for ALK-rearranged patients with c-Met overexpression of ≥50% of tumor cells of strong immunostaining.

The frequency of patients with c-Met overexpression were 29.2 and 58.8% of ALK-rearranged patients respectively in Tsuta and Feng studies, while was 10.0% (16/160) in our research [20, 36]. There were several noticeable differences between these studies and our results. Tsuta et al. defined c-Met positivity as staining in≥10% of tumor cells without concerning staining intensity, while Feng study as having ≥50% of tumor cells of immunostaining with moderate or intensity [20, 36]. However, patients with c-Met of ≥50% of tumor cells of intensity immunostaining obtained more clinical benefit from c-Met inhibitors, even achieving the ORR of 50% in several studies [28, 41]. Thus, in our study, patients with ≥50% of tumor cells of intensity immunostaining were defined as c-Met overexpression. Besides, Feng et al. study was conducted in 19 ALK-rearranged Western NSCLC patients with early or advanced stages, whereas ours was in 160 ALK-positive Eastern metastatic cases. The variations in the frequency of c-Met overexpression in ALK-positive patients were likely related to different definitions of c-Met overexpression and population investigated.

Crizotinib simultaneously inhibits the activation of ALK and c-Met pathway. ALK-rearranged patients obtained ORR of 74% and median PFS of 10.9 months with first-line crizotinib, while those with de novo c-Met overexpression experienced ORR of 58% [39, 41] . Thus, it is possible that ALK-rearranged tumors with c-Met overexpression may be shrunk largely with the treatment of crizotinib. However, only few limited cases were reported the response to crizotinib for ALK-rearranged patients with c-Met overexpression. Feng et al. study demonstrated 2 CRs and 4 PRs with crizotinib in 6 ALK-rearranged patients with c-Met overexpression [36]. However, the phase III METLung trail showed that onartuzumab plus erlotinib did not improve ORR, PFS and OS, compared with erlotinib in patients with c-Met overexpression [23]. Disease progression to crizotinib was reported in an ALK-rearranged patient with c-Met overexpression and Her-2 amplification [42].The clinical and therapeutic implications of c-Met overexpression underlay in ALK- rearranged NSCLC patients were undiscovered. Our results showed that ALK-rearranged patients with c-Met overexpression obtained significant objective response rate and median OS and a trend of superiority in terms of PFS with treatment of crizotinib, compared with those who without c-Met overexpression. Regardless, it would be interesting to further explore the response to the potential combination therapy of c-Met inhibitor plus ALK inhibitor, especially the second-generation ones, such as ceritinib or alectinib, which does not possess c-Met inhibitory activity.

However, there were several limitations in the present study. First, we focused on only a small sample-size of ALK-rearranged patients with c-Met overexpression. In addition, this was a retrospective study. Furthermore, the status of c-Met exon 14 skipping mutations in patients of our research was not detected for the lack of tissue samples. Finally, it is difficult to compare each ALK variants or other gene profiles for insufficient tissues in this study.

Conclusion

Our study demonstrated that c-Met overexpression of ≥50% of tumor cells of strong staining exists in a small population of advanced ALK-rearranged NSCLC. There may be a trend of favorable efficacy of crizotinib for advanced ALK-rearranged patients co-existing with c-Met overexpression. Further investigations are warranted to validate our findings and to elucidate molecular mechanisms.

Abbreviations

- ALK + c-Met-:

-

ALK-rearranged patients without c-Met overexpression

- ALK + c-Met+:

-

ALK-rearranged patients with c-Met overexpression

- ALK:

-

Anaplastic lymphoma kinase

- c-Met:

-

cellular-mesenchymal-epithelial transition

- CR:

-

Complete response

- DCR:

-

Disease control rate

- ECOG:

-

Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group

- EGFR:

-

Epidermal growth factor receptor

- EGFR-TKI:

-

EGFR-tyrosine kinase inhibitor

- FISH:

-

Fluorescent in situ hybridization

- GLCI:

-

The Guangdong Lung Cancer Institute

- IHC:

-

Ventana immunohistochemistry

- KRAS:

-

Kirsten rat sarcoma viral oncogene homolog

- NSCLC:

-

Non-small cell lung cancer

- ORR:

-

Objective response rate

- OS:

-

Overall survival

- PD:

-

Progressive disease

- PFS:

-

Progression-free survival

- PR:

-

Partial response

- PS:

-

Performance status

- RACE PCR:

-

Rapid amplification of cDNA ends coupled polymerase chain reaction

- RECIST:

-

Response evaluation criteria in solid tumors

- SD:

-

Stable disease

References

Li TH, Kung HJ, Mack PC, Gandara DR. Genotyping and genomic profiling of non-small-cell lung cancer: implications for current and future therapies. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31(8):1039–49.

Soda M, Choi YL, Enomoto M, Takada S, Yamashita Y, Ishikawa S, et al. Identification of the transforming EML4-ALK fusion gene in non-small-cell lung cancer. Nature. 2007;448(7153):561–6.

Horn L, Pao W. EML4-ALK: honing in on a new target in non-small-cell lung cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27(26):4232–5.

Shaw AT, Yeap BY, Mino-Kenudson M, Digumarthy SR, Costa DB, Heist RS, et al. Clinical features and outcome of patients with non–small-cell lung Cancer who harbor EML4-ALK. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27(26):4247–53.

Zhang XC, Lu S, Zhang L, Wang CL, Cheng Y, Li GD, et al. Consensus on dignosis for ALK positive non-small cell lung cancer in China, the 2013 version. Zhonghua Bing Li Xue Za Zhi. 2013;42(6):402–6.

Takeuchi S, Wang W, Li Q, Yamada T, Kita K, Donev IS, et al. Dual inhibition of Met kinase and angiogenesis to overcome HGF-induced EGFR-TKI resistance in EGFR mutant lung cancer. Am J Pathol. 2012;181(3):1034–43.

Ma PC, Maulik G, Christensen J, Salgia R. c-Met: structure, functions and potential for therapeutic inhibition. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 2003;22(4):309–25.

Maulik G, Shrikhande A, Kijima T, Ma PC, Morrison PT, Salgia R. Role of the hepatocyte growth factor receptor, c-Met, in oncogenesis and potential for therapeutic inhibition. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 2002;13(1):41–59.

Feng Y, Thiagarajan PS, Ma PC. MET signaling: novel targeted inhibition and its clinical development in lung cancer. J Thorac Oncol. 2012;7(2):459–67.

Derksen PW, de Gorter DJ, Meijer HP, Bende RJ, van Dijk M, Lokhorst HM, et al. The hepatocyte growth factor/Met pathway controls proliferation and apoptosis in multiple myeloma. Leukemia. 2003;17(4):764–74.

Beau-Faller M, Ruppert AM, Voegeli AC, Neuville A, Meyer N, Guerin E, et al. MET gene copy number in non-small cell lung cancer: molecular analysis in a targeted tyrosine kinase inhibitor naive cohort. J Thorac Oncol. 2008;3(4):331–9.

Tong JH, Yeung SF, Chan AW, Chung LY, Chau SL, Lung RW, et al. MET amplification and exon 14 splice site mutation define unique molecular subgroups of non-small cell lung carcinoma with poor prognosis. Clin Cancer Res. 2016;22(12):3048–56.

Cappuzzo F, Janne PA, Skokan M, Finocchiaro G, Rossi E, Ligorio C, et al. MET increased gene copy number and primary resistance to gefitinib therapy in non-small-cell lung cancer patients. Ann Oncol. 2009;20(2):298–304.

Tachibana K, Minami Y, Shiba-Ishii A, Kano J, Nakazato Y, Sato Y, et al. Abnormality of the hepatocyte growth factor/MET pathway in pulmonary adenocarcinogenesis. Lung Cancer. 2012;75(2):181–8.

Kubo T, Yamamoto H, Lockwood WW, Valencia I, Soh J, Peyton M, et al. MET gene amplification or EGFR mutation activate MET in lung cancers untreated with EGFR tyrosine kinase inhibitors. Int J Cancer. 2009;124(8):1778–84.

Li AN, Gao HF, Wu YL. Targeting the MET pathway for potential treatment of NSCLC. Expert Opin Ther Tar. 2015;19(5):663–74.

Liu SY, Gou LY, Li AN, Lou NN, Gao HF, Su J, et al. The unique characteristics of MET exon 14 mutation in Chinese patients with NSCLC. J Thorac Oncol. 2016;11(9):1503–10.

Schrock AB, Frampton GM, Suh J, Chalmers ZR, Rosenzweig M, Erlich RL, et al. Characterization of 298 patients with lung Cancer harboring MET exon 14 skipping alterations. J Thorac Oncol. 2016;11(9):1493–502.

Awad MM, Oxnard GR, Jackman DM, Savukoski DO, Hall D, Shivdasani P, et al. MET exon 14 mutations in non-small-cell lung Cancer are associated with advanced age and stage-dependent MET genomic amplification and c-Met overexpression. J Clin Oncol. 2016;34(7):721–30.

Tsuta K, Kozu Y, Mimae T, Yoshida A, Kohno T, Sekine I, et al. c-MET/Phospho-MET protein expression and MET gene copy number in non-small cell lung carcinomas. J Thorac Oncol. 2012;7(2):331–9.

Sun W, Song L, Ai T, Zhang Y, Gao Y, Cui J. Prognostic value of MET, cyclin D1 and MET gene copy number in non-small cell lung cancer. J Biomed Res. 2013;27(3):220–30.

Huang L, An SJ, Chen ZH, Su J, Yan HH, Wu YL. MET expression plays differing roles in non-small-cell lung Cancer patients with or without EGFR mutation. J Thorac Oncol. 2014;9(5):725–8.

Spigel DR, Edelman MJ, Mok T, O'Byrne K, Paz-Ares L, Yu WL, et al. Treatment rationale study design for the MetLung trial: a randomized, double-blind phase III study of Onartuzumab (MetMAb) in combination with Erlotinib versus Erlotinib alone in patients who have received standard chemotherapy for stage IIIB or IV Met-positive non-small-cell lung Cancer. Clin Lung Cancer. 2012;13(6):500–4.

Koeppen H, Yu W, Zha J, Pandita A, Penuel E, Rangell L, et al. Biomarker analyses from a placebo-controlled phase II study evaluating Erlotinib Onartuzumab in advanced non-small cell lung Cancer: MET expression levels are predictive of patient benefit. Clin Cancer Res. 2014;20(17):4488–98.

Spigel DR, Edelman MJ, O'Byrne K, Paz-Ares L, Mocci S, Phan S, et al. Results from the phase III randomized trial of Onartuzumab plus Erlotinib versus Erlotinib in previously treated stage IIIB or IV non-small-cell lung Cancer: METLung. J Clin Oncol. 2017;35(4):412–20.

Scagliotti G, von Pawel J, Novello S, Ramlau R, Favaretto A, Barlesi F, et al. Phase III multinational, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study of Tivantinib (ARQ 197) plus Erlotinib versus Erlotinib alone in previously treated patients with locally advanced or metastatic nonsquamous non–small-cell lung Cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2015;33(24):2667–74.

Wu YL, Yang JC, Park K, Xu L, Bladt F, Johne A, et al. Phase I/II multicenter, randomized, open-label trial of the c-Met inhibitor MSC2156119J and gefitinib versus chemotherapy as second-line treatment in patients with MET-positive (MET+), locally advanced, or metastatic non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) with epidermal growth factor mutation (EGFRm+) and progression on gefitinib. J Clin Oncol. 2014;32(suppl):s8121.

Wu YL, Kim D, Felip E, Li Zhang XL, Zhou CC, Lee DH, et al. Phase (Ph) II safety and efficacy results of a single-arm ph ib/II study of capmatinib (INC280) + gefitinib in patients (pts) with EGFR-mutated (mut), cMET-positive (cMET+) non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC)(abstract). J Clin Oncol. 2016;34(suppl):9020.

Engelman JA, Zejnullahu K, Mitsudomi T, Song Y, Hyland C, Park JO, et al. MET amplification leads to gefitinib resistance in lung cancer by activating ERBB3 signaling. Science. 2007;316(5827):1039–43.

Rodig SJ, Mino-Kenudson M, Dacic S, Yeap BY, Shaw A, Barletta JA, et al. Unique clinicopathologic features characterize ALK-rearranged lung adenocarcinoma in the western population. Clin Cancer Res. 2009;15(16):5216–23.

Inamura K, Takeuchi K, Togashi Y, Hatano S, Ninomiya H, Motoi N, et al. EML4-ALK lung cancers are characterized by rare other mutations, a TTF-1 cell lineage, an acinar histology, and young onset. Mod Pathol. 2009;22(4):508–15.

Takeuchi K, Choi YL, Soda M, Inamura K, Togashi Y, Hatano S, et al. Multiplex reverse transcription-PCR screening for EML4-ALK fusion transcripts. Clin Cancer Res. 2008;14(20):6618–24.

Zhang XC, Zhang S, Yang XN, Yang JJ, Zhou Q, Yin L, et al. Fusion of EML4 and ALK is associated with development of lung adenocarcinomas lacking EGFR and KRAS mutations and is correlated with ALK expression. Mol Cancer. 2010;9:188.

Lee JK, Kim TM, Koh Y, Lee S, Kim D, Jeon Y, et al. Differential sensitivities to tyrosine kinase inhibitors in NSCLC harboring EGFR mutation and ALK translocation. Lung Cancer. 2012;77(2):460–3.

Yang JJ, Zhang XC, Su J, Xu CR, Zhou Q, Tian HX, et al. Lung cancers with concomitant EGFR mutations and ALK rearrangements: diverse responses to EGFR-TKI and Crizotinib in relation to diverse receptors phosphorylation. Clin Cancer Res. 2014;20(5):1383–92.

Feng Y, Minca EC, Lanigan C, Liu A, Zhang W, Yin L, et al. High MET receptor expression but not gene amplification in ALK 2p23 rearrangement positive non–small-cell lung Cancer. J Thorac Oncol. 2014;9(5):646–53.

Kwak EL, Bang YJ, Camidge DR, Shaw AT, Solomon B, Maki RG, et al. Anaplastic lymphoma kinase inhibition in non-small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2010;363(18):1693–703.

Camidge DR, Bang YJ, Kwak EL, Iafrate AJ, Varella-Garcia M, Fox SB, et al. Activity and safety of crizotinib in patients with ALK-positive non-small-cell lung cancer: updated results from a phase 1 study. Lancet Oncol. 2012;13(10):1011–9.

Solomon BJ, Mok T, Kim DW, Wu YL, Nakagawa K, Mekhail T, et al. First-line crizotinib versus chemotherapy in ALK-positive lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2014;371(23):2167–77.

Kim D, Ahn M, Shi Y, De Pas TM, Yang P, Riely GJ, et al. Results of a global phase II study with crizotinib in advanced ALK-positive non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC). J Clin Oncol. 2012;30(suppl):7533.

Li AN, Yang JJ, Zhang XC, Wu YL. Crizotinib in advanced non-small-cell lung cancer with de novo c-Met overexpression. J Clin Oncol. 2015;33(suppl):8090.

Gu FF, Zhang Y, Liu YY, Hong XH, Liang JY, Tong F, et al. Lung adenocarcinoma harboring concomitant SPTBN1-ALK fusion, c-Met overexpression, and HER-2 amplification with inherent resistance to crizotinib, chemotherapy, and radiotherapy. J Hematol Oncol. 2016;9(1):66.

Vallieres E, Shepherd FA, Crowley J, Van Houtte P, Postmus PE, Carney D, et al. The IASLC lung Cancer staging project: proposals regarding the relevance of TNM in the pathologic staging of small cell lung cancer in the forthcoming (seventh) edition of the TNM classification for lung cancer. J Thorac Oncol. 2009;4(9):1049–59.

Eisenhauer EA, Therasse P, Bogaerts J, Schwartz LH, Sargent D, Ford R, et al. New response evaluation criteria in solid tumours: revised RECIST guideline (version 1.1). Eur J Cancer. 2009;45(2):228–47.

Cappuzzo F, Marchetti A, Skokan M, Rossi E, Gajapathy S, Felicioni L, et al. Increased MET gene copy number negatively affects survival of surgically resected non-small-cell lung cancer patients. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27(10):1667–74.

Jiang SX, Yamashita K, Yamamoto M, Piao CJ, Umezawa A, Saegusa M, et al. EGFR genetic heterogeneity of nonsmall cell lung cancers contributing to acquired gefitinib resistance. Int J Cancer. 2008;123(11):2480–6.

Acknowledgements

We thank the patients in our study, their family members, and the staffs of Guangdong Lung Cancer Institute and Peking University Cancer Hospital for their contribution to this study.

Funding

This study was sponsored from the Project of the National Natural Science Funding of China (Grant No. 81472207), the Special Fund for Research in the Public Interest from the National Health and Family Planning Commission of PRC (Grant No. 201402031), Key Lab System Project of Guangdong Science and Technology Department–Guangdong Provincial Key Lab of Translational Medicine in Lung Cancer (Grant No. 2012A061400006/2017B030314120), Research Funds from the Guangzhou Science and Technology Bureau (Grant No. 201607010391 and 2016B020237006). These funding were involved in the study design, interpretation of the data, and preparation of the manuscript.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets during and/or analyzed during the current study available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

YLW, JJY, RLC, XCZ and JZ contributed to the conception and design. RLC, NNL, HJC, XY, JS, ZX, QZ, HYT, WZZ and WBG were involved in gathering data. RLC and HHY performed data analysis. The manuscript was written by RLC and JJY. All the authors participated in the interpretation of the study results, and in the drafting, critical revision, and approval of the final version of the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the Guangdong General Hospital and all patients provided written informed consents.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Chen, RL., Zhao, J., Zhang, XC. et al. Crizotinib in advanced non-small-cell lung cancer with concomitant ALK rearrangement and c-Met overexpression. BMC Cancer 18, 1171 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12885-018-5078-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12885-018-5078-y