Abstract

Background

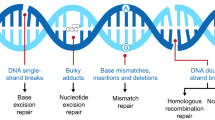

Personalized therapy considering clinical and genetic patient characteristics will further improve breast cancer survival. Two widely used treatments, chemotherapy and radiotherapy, can induce oxidative DNA damage and, if not repaired, cell death. Since base excision repair (BER) activity is specific for oxidative DNA damage, we hypothesized that germline genetic variation in this pathway will affect breast cancer-specific survival depending on treatment.

Methods

We assessed in 1,408 postmenopausal breast cancer patients from the German MARIE study whether cancer specific survival after adjuvant chemotherapy, anthracycline chemotherapy, and radiotherapy is modulated by 127 Single Nucleotide Polymorphisms (SNPs) in 21 BER genes. For SNPs with interaction terms showing p < 0.1 (likelihood ratio test) using multivariable Cox proportional hazard analyses, replication in 6,392 patients from nine studies of the Breast Cancer Association Consortium (BCAC) was performed.

Results

rs878156 in PARP2 showed a differential effect by chemotherapy (p = 0.093) and was replicated in BCAC studies (p = 0.009; combined analysis p = 0.002). Compared to non-carriers, carriers of the variant G allele (minor allele frequency = 0.07) showed better survival after chemotherapy (combined allelic hazard ratio (HR) = 0.75, 95 % 0.53–1.07) and poorer survival when not treated with chemotherapy (HR = 1.42, 95 % 1.08–1.85). A similar effect modification by rs878156 was observed for anthracycline-based chemotherapy in both MARIE and BCAC, with improved survival in carriers (combined allelic HR = 0.73, 95 % CI 0.40–1.32). None of the SNPs showed significant differential effects by radiotherapy.

Conclusions

Our data suggest for the first time that a SNP in PARP2, rs878156, may together with other genetic variants modulate cancer specific survival in breast cancer patients depending on chemotherapy. These germline SNPs could contribute towards the design of predictive tests for breast cancer patients.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Breast cancer ranks among the most important causes of cancer death in women worldwide, but data from recent years reveal that mortality rates are steadily decreasing in Northern European and American countries [1, 2]. This increase in survival can be attributed to both progress in early detection and improved treatment protocols using classical cytostatics and new targeted drugs for estrogen receptor positive tumours and HER2 positive tumours [3, 4]. Current efforts are thus aimed to further advance therapy by developing new drugs but also by considering genetic determinants present in germ line and tumour.

Two major components of past and current breast cancer treatment protocols are chemotherapeutics such as anthracyclines like epirubicin or doxorubicin and ionizing radiation. Their efficiency is based on their strong potential to induce cellular DNA damage. Among other mechanisms, both treatments produce reactive oxygen species (ROS) by iron-mediated oxidation of the doxorubicin quinone structure to a semiquinone radical [5, 6] or by radiation-induced ionization of water [7]. In addition, doxorubicin directly forms radicals via an doxorubicin-iron complex which catalyses the conversion of hydrogen peroxide to hydroxylradicals by repeated redox cycles between Fe (II) and Fe (III) forms [5, 6]. The resulting superoxide radicals, hydrogen peroxides, and hydroxyl radicals quickly react with cellular macromolecules, especially with DNA [8, 9]. The oxidized DNA bases if not removed in time will result in cell cycle arrest and cell death. Thus, the base excision repair (BER) system with its DNA glycosylases specific for various types of oxidative DNA damage is one of the crucial determinants of tumour chemotherapy [10, 11].

Deficiencies in double strand break repair are well described for hereditary and sporadic breast cancer cases [12, 13]. There are also recent reports of genetic variation in BER genes being associated with breast cancer risk [14–18]. Therefore, we hypothesized those single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) in BER genes might contribute to altered DNA repair efficiency, which will affect therapeutic success and cancer specific survival in breast cancer patients. In a prospective breast cancer patient cohort from Germany [19], we assessed whether cancer specific survival is modulated by genetic variation in BER genes according to the therapy applied, especially anthracycline-based chemotherapy and radiotherapy. Although radiotherapy primarily acts on local recurrence, it may nevertheless in consequence have an impact on cancer specific survival [20]. Significant associations were tested for replication in studies of the Breast Cancer Association Consortium (BCAC).

Methods

MARIE study population

Breast cancer patients diagnosed at ages 50–74 years between 2001 and 2005 were recruited in the German two-centre (Hamburg and Rhine-Neckar-Karlsruhe region) population-based MARIE study [19] and prospectively followed-up until end of 2009 [21]. The study was approved by the ethics committees of the University of Heidelberg (230/2001 and S-009/2009), the Hamburg Medical Council (1791 and PV3176), and the Medical Board of the State of Rheinland-Pfalz (837.135.09 (6640)) and all participants gave written informed consent.

Vital status was assessed via population registries (100 % completeness) and cause of death abstracted from death certificates obtained from the health offices. Of the 3,813 postmenopausal breast cancer patients, genotype information on SNPs in DNA repair genes was available for 1,639 patients. We further excluded patients with previous non-breast tumour (n = 114) and with in situ breast tumour (n = 117), resulting in 1,408 patients available for this analysis (Fig. 1).

SNPs selection and genotyping

The initial SNP panel comprised 135 SNPs in 21 base excision repair genes (APEX1, APEX2, CDKN1A, LIG3, MBD4, MPG, MUTYH, NEIL1, NEIL2, NTHL1, OGG1, PARP1, PARP2, PNKP, POLB, POLG, SMUG1, TDG, TP53, UNG, XRCC1) [13]. SNPs were mainly common tagging SNPs to capture genetic variation across the genes, plus additional coding SNPs. The SNP selection using HapMap reference data (The International HapMap Consortium 200318; http://www.hapmap.org, HapMap Data Release 22/phase II, NCBI B36 assembly, dbSNP b126) was performed as described previously [15, 22]. Genotyping was conducted using the Illumina GoldenGate Assay. Quality control criteria included barcode labelled plates, 2 % duplicate samples (100 % concordance) and call rates (>96 %). SNPs with poor genotyping clustering were omitted from the analysis [23]. After quality control, genotype data of 127 SNPs in 21 BER genes was available for analysis.

Statistical analysis of MARIE

Statistical analyses were conducted using SAS 9.2 for MARIE and 9.3 for BCAC data. We used time-to-event analysis (Cox proportional hazards models) to assess the association between genotype and breast cancer specific death, accounting for differences in time between diagnosis and baseline interview date (left truncation: delayed entry models). A log-additive mode of inheritance was assumed for the SNPs.

All models were stratified by age at cancer diagnosis (see Table 1) and study centre (Hamburg and Rhine-Neckar-Karlsruhe region), and adjusted for the following covariates (categorically), obtained by backward selection (p <0.05): tumour size, nodal status, baseline metastases status, tumour grade, estrogen/progesterone receptor status, mode of detection, smoking status, menopausal hormone therapy as well as radiotherapy and (anthracycline-based) chemotherapy (including both adjuvant and neoadjuvant treatment).

We investigated possible differential associations according to chemotherapy overall and anthracycline-based chemotherapy, as well as radiotherapy, using multiplicative interaction terms of SNP * [treatment] (i.e. radiotherapy, chemotherapy, anthracycline-based chemotherapy coded as yes/no). Models with and without interaction term were compared using a likelihood ratio test (LRT). For SNPs with interaction terms showing p-value <0.1 in model comparison, stratified analyses according to therapy were conducted to quantify the SNP association with survival according to therapy.

Replication in the Breast Cancer Association Consortium (BCAC)

SNPs with interaction terms showing p <0.1 in the MARIE study were included for replication using studies of BCAC [24]. Data harmonization was applied to all studies in a multi-step process according to a common data dictionary.

Studies were eligible if they had available data on primary invasive breast cancer, genotypes, age, vital status, follow-up, tumour characteristics, and treatment. We restricted the BCAC study population to women aged 50 or older at diagnosis to make it comparable with the postmenopausal MARIE study population. Follow-up time was restricted to 15 years. We further excluded studies with less than ten events, resulting in nine studies (6,392 patients with 526 events) available for this analysis (Additional file 1: Figure S1, Additional file 2: Table S1). All studies were approved by the relevant ethics committees and all participants gave written informed consent.

Genotype data for eight SNPs were available from genotyping conducted using the Illumina iSelect array as part of a large-scale project, the Collaborative Oncological Gene-environment Study (COGS) with thorough centralized quality control measures [24]. Imputed genotypes were available for the other six SNPs using the 1000 genomes project March 2012 release as the reference dataset [25]. The two-stage imputation procedure included the use of SHAPEIT to derive phased genotypes and IMPUTEv2 to perform the imputation on the phased data [26]. Since harmonized individual data were available from the BCAC studies, associations were assessed by pooled analysis using Cox proportional hazard models (allowing for study entry by left truncation) stratified by study and adjusted for tumour stage, tumour grade, ER status, age, principal components to account for population substructure, and radio- and/or chemotherapy.

Meta-analysis

Meta-analyses were conducted to combine the estimates from the MARIE study and the replication BCAC studies, applying fixed effects models, and to determine study heterogeneity. Study heterogeneity was assessed using I2/tau2 statistics [27, 28] and forest plots were generated using R (version 2.15.2).

Results

A description of the patient characteristics of the MARIE study population is provided in Table 1. After a median follow-up time of 72 months (min-max: 3–108 months), 147 patients died from breast cancer and additionally 50 due to other causes. Compared to the total study population, patients who died from breast cancer were more likely to have advanced tumours (larger tumour size, higher nodal status, more often M1 status, poorer grading) and hormone-receptor negative tumours, and more often received chemotherapy and less often radiotherapy.

Effect modification by chemotherapy

In the MARIE study, we identified 14 SNPs in five genes (OGG1, PARP2, POLB, SMUG1, XRCC1) with differential effects by any type of chemotherapy (p <0.1, Table 2). One SNP in PARP2 (rs878156) showed a differential association (p = 0.093) and was associated with improved survival in MARIE patients who received chemotherapy (HRchemo 0.88, 95 % CI 0.50–1.54) but higher mortality in patients not treated with chemotherapy (HRno_chemo 2.78, 95 % CI 1.15–6.73). The differential association of this SNP with breast cancer specific mortality was successfully replicated in the BCAC studies (p = 0.009, HRchemo 0.67, 95 % CI 0.43–1.06 vs. HRno_chemo 1.32, 95 % CI 1.00–1.75). Using a meta-analysis approach, the combined allelic hazard ratios of rs878156 for MARIE and BCAC studies were 0.75 (95 % CI 0.53–1.07) in patients who received chemotherapy and 1.42 (95 % CI 1.08–1.85) in patients not treated with chemotherapy and clearly different (p = 0.002) (Fig. 2a, b). There was no evidence of study heterogeneity in a meta-analysis across BCAC studies (Additional file 3: Figure S2). Two SNPs in XRCC1 showed differential effects in both MARIE and BCAC, however, the SNP associations showed an opposite direction in the BCAC studies to that found in MARIE (Table 2). These two SNPs are in high linkage disequilibrium (r2 = 0.876). For XRCC1 rs3213356, we observed significant heterogeneity between the associations observed in the MARIE study and that of the BCAC studies (Fig. 3a, b), confirming the lack of replication, but no study heterogeneity within BCAC studies (Additional file 4: Figure S3).

Meta-analysis of PARP2 rs878156 and breast cancer prognosis according to chemotherapy. Forest plot of of the combined hazard ratios and 95 % confidence intervals for PARP2 rs878156 in the discovery MARIE study and the replication in Breast Cancer Association Consortium (BCAC) using fixed effect model, according to treatment, i.e. no chemotherapy (a), any type of chemotherapy (b), and anthracycline-based chemotherapy (c). The associations for the BCAC studies were based on pooled analysis stratified by study and adjusted for covariables (see Methods)

Meta-analysis of XRCC1 rs3213356 and breast cancer prognosis according to chemotherapy. Forest plot of meta-analysis of hazard ratios and 95 % confidence intervals for XRCC1 rs3213356 in the discovery MARIE study and the replication in Breast Cancer Association Consortium (BCAC) using fixed effect model, according to treatment, i.e. no chemotherapy (a), any type of chemotherapy (b) and anthracycline-based chemotherapy . The associations for the BCAC studies were based on pooled analysis stratified by study and adjusted for covariables (see Methods)

As the BER system is particularly relevant for oxidative DNA damage due to anthracycline-based chemotherapy, we additionally investigated effect modification by this specific type of chemotherapy, which accounts for about 72 % of chemotherapy regimens. Thirteen SNPs were associated with p < 0.1 for breast cancer specific mortality according to anthracycline-based chemotherapy in the MARIE study, nine of them located in the five genes OGG1, PARP2, POLB, SMUG1, XRCC1 already indicated above and five SNPs in additional three genes (CDKN1A, LIG3, MBD4) (Table 3). Solely the PARP2 SNP rs878156 was consistently associated with improved prognosis after anthracycline-based chemotherapy in both MARIE and BCAC (HRanthra 0.82 and 0.55; pint = 0.055 and 0.036, respectively), compared to the poor prognosis for patients without any chemotherapy. The combined allelic HR was 0.73, 95 % CI 0.40–1.32, for the SNP associated survival after anthracycline-based chemotherapy (Fig. 2c), which was not different from that for any chemotherapy but different compared to that for no chemotherapy (Fig. 2a).

Effect modification by radiotherapy

Associations were different by radiotherapy (p <0.1) for 14 SNPs in five genes (APEX1, NEIL2, PARP2, TDG, UNG) in the MARIE study (Additional file 5: Table S2). None of the differential associations were replicated in the BCAC studies.

Discussion

Using the large cohort of MARIE postmenopausal breast cancer patients for discovery and patient cohorts from studies in BCAC for replication, we found evidence for differential association of rs878156 in the poly (ADP-ribose) polymerase PARP2 gene with breast cancer specific mortality according to adjuvant chemotherapy. Compared to non-carriers, carriers of the variant G allele experienced improved survival when treated with chemotherapy and poorer survival when they were not treated. A similar effect modification by PARP2 rs878156 was observed for breast cancer specific mortality after anthracycline-based chemotherapy. To our knowledge, this is the first report of a PARP2 SNP that is potentially predictive for treatment outcome of anthracycline-based chemotherapy. Studies in breast tumours on associations between PARP2 protein or mRNA expression and prognosis are supportive of our data although results are not conclusive [29, 30].

rs878156 is an intragenic SNP in PARP2 (minor allele frequency of about 10 %) located 10 base pairs distal from an intron-exon boundary without reported functional impact. Recent research showed that intragenic SNPs which are located even up to 1000 base pairs away from the intron-exon boundary can still affect splicing of the RNA transcript thus modifying protein levels or function [31, 32]. Similar effects are also conceivable for rs878156. This assumption is supported by an increased DNase I sensitivity, high sequence conservation of the SNP region and additional spliced ESTs indicated in the UCSC genome browser (https://genome-euro.ucsc.edu, hg19) but has still to be confirmed experimentally. Regarding PARP2 function, it catalyses, together with PARP1, the poly (ADP-ribosyl) ation of various proteins involved in genome surveillance, especially base excision repair proteins, histones and transcription factors, and in this way modulates the activity of these proteins. Both PARP proteins are induced by DNA-strand interruptions but act on different lesions, such as PARP1 on single-strand breaks or PARP2 on gaps and flap structures [33]. PARP proteins share considerable similarity in the catalytic domain but have different DNA binding domains [33, 34]. There are several inhibitors available affecting both enzymes and some of them are already used in tumour therapy with promising results [35].

As PARP2 contributes to only 5–10 % of the total cellular PARP activity [34], it is difficult to estimate specific PARP2 effects. Therefore, if PARP2 protein is affected by rs878156, only minor changes are to be expected in normal cells. In case of oxidative damage due to therapy with anthracyclines, however, repair of therapy-related damage might be impaired and therapy efficiency increased. In addition, breast cancer cells frequently harbour genetic or epigenetic modifications that cause DNA repair deficiencies, e.g. mutations or promoter methylation of BRCA1/2, TP53, ATM, RAD51C, PALB2 [12, 36] or changes in mRNA and protein levels of BER genes [10, 37]. The two repair defects taken together, the tumour-related somatic one and the one caused by the variant germline allele could confer a strong genomic instability to tumour cells, which will increase tumour progression and decrease survival if the patient is not treated. In case of chemotherapy, synthetic lethality could emerge, increasing tumour control by the treatment and thereby improving patient survival, a similar synthetic lethal effect as observed for BRCA1-deficient breast tumours treated with PARP inhibitors [11, 13, 38].

Another significant differential association by any chemotherapy was found for the two highly linked XRCC1 intronic SNPs, rs3213355 and rs3213356, in MARIE. The observed differential association was not formally replicated in the BCAC studies since the direction of the HRs in the subgroups by chemotherapy in BCAC was opposite to that in the MARIE study. Therefore, the observation of differential effects for these two XRCC1 SNPs in BCAC studies is a new finding, which requires validation in independent studies. Further investigation of genetic variants in XRCC1 is warranted since a prognostic role of XRCC1 for breast cancer survival has been reported for the XRCC1 rs25487 SNP, which causes an amino acid change (e.g. [39–41]). The XRCC1 variants rs25487 and rs3213356 are not in high linkage disequilibrium. Studies have however reported inconsistent results for the rs25487 risk variant, which could be attributable to investigations in different patient groups with different therapy regimens or focus on patient subgroups like those with metastatic breast cancer.

While the high completeness of follow-up data is a major strength of the MARIE study, our study power to detect weak effects might have been limited with a median follow-up time of only 6 years and 147 events. The effect modulation of therapy response by rs878156 was however confirmed using an independent cohort of more than 6000 breast cancer patients including additional 526 events from BCAC, which demonstrates the robustness of the observed association. As original data collection in the consortium was not standardized and comprehensive across all these studies, we accounted for this limitation through thorough data harmonization and restriction to postmenopausal women aged 50 years and older. In addition, differences in patient characteristics and treatment factors were adjusted for in the statistical analysis to reduce any bias due to study and patient heterogeneity. Although the differential association with rs878156 is not significant if accounting for both the number of SNPs and the different therapies tested, the genes selected were hypothesis driven and thus associated with a high prior probability. Nevertheless, our results should be validated further in clinical studies with homogenous treatment protocols.

Conclusions

We showed for the first time that the intronic rs878156 SNP in the BER gene PARP2 can modulate cancer specific survival in breast cancer patients depending on chemotherapy. Thus, if confirmed, this SNP together with further genetic variants that influence prognosis may help to improve treatment decisions in the future. Furthermore, as breast cancer is a heterogeneous disease showing different mutation patterns often involving DNA repair genes, characterization of both tumour and inherited genomes will be required for an improved personalized and targeted treatment.

Abbreviations

- BCAC:

-

Breast Cancer Association Consortium

- BER:

-

base excision repair

- PARP2:

-

poly (ADP-ribose) polymerase 2

- p int :

-

p-value for interaction

- SNP:

-

single nucleotide polymorphism

References

Effects of chemotherapy and hormonal therapy for early breast cancer on recurrence and 15-year survival. an overview of the randomised trials. Lancet. 2005;365(9472):1687–717.

Holleczek B, Jansen L, Brenner H. Breast cancer survival in Germany: a population-based high resolution study from Saarland. PLoS One. 2013;8(7):e70680.

Ferreira AR, Saini KS, Metzger-Filho O. Treatment of early-stage HER2+ breast cancer-an evolving field. Ecancermedicalscience. 2015;9:523.

Schiavon G, Smith IE. Status of adjuvant endocrine therapy for breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res. 2014;16(2):206.

Ichikawa Y, Ghanefar M, Bayeva M, Wu R, Khechaduri A, Naga Prasad SV, et al. Cardiotoxicity of doxorubicin is mediated through mitochondrial iron accumulation. J Clin Invest. 2014;124(2):617–30.

Yang F, Teves SS, Kemp CJ, Henikoff S. Doxorubicin, DNA torsion, and chromatin dynamics. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2014;1845(1):84–9.

Ward F. Ionizing radiation damage to DNA. In: Dizdaroglu M, Karakaya AE, editors. Advances in DNA damage and repair. New York: Kluwer Academic/Plenum Publishers; 1999. p. 431–9.

Gajewski E, Gaur S, Akman SA, Matsumoto L, van Balgooy JN, Doroshow JH. Oxidative DNA base damage in MCF-10A breast epithelial cells at clinically achievable concentrations of doxorubicin. Biochem Pharmacol. 2007;73(12):1947–56.

Manjanatha MG, Bishop ME, Pearce MG, Kulkarni R, Lyn-Cook LE, Ding W. Genotoxicity of doxorubicin in F344 rats by combining the comet assay, flow-cytometric peripheral blood micronucleus test, and pathway-focused gene expression profiling. Environ Mol Mutagen. 2014;55(1):24–34.

Abdel-Fatah TM, Perry C, Arora A, Thompson N, Doherty R, Moseley PM, et al. Is there a role for base excision repair in estrogen/estrogen receptor-driven breast cancers? Antioxid Redox Signal. 2014;21(16):2262–8.

Hosoya N, Miyagawa K. Targeting DNA damage response in cancer therapy. Cancer Sci. 2014;105(4):370–88.

Liu C, Srihari S, Cao KA, Chenevix-Trench G, Simpson PT, Ragan MA, et al. A fine-scale dissection of the DNA double-strand break repair machinery and its implications for breast cancer therapy. Nucleic Acids Res. 2014;42(10):6106–27.

Lord CJ, Ashworth A. Mechanisms of resistance to therapies targeting BRCA-mutant cancers. Nat Med. 2013;19(11):1381–8.

Peng Q, Lu Y, Lao X, Chen Z, Li R, Sui J, et al. Association between OGG1 Ser326Cys and APEX1 Asp148Glu polymorphisms and breast cancer risk: a meta-analysis. Diagn Pathol. 2014;9:108.

Popanda O, Seibold P, Nikolov I, Oakes CC, Burwinkel B, Hausmann S, et al. Germline variants of base excision repair genes and breast cancer: A polymorphism in DNA polymerase gamma modifies gene expression and breast cancer risk. Int J Cancer. 2013;132(1):55–62.

Sangrajrang S, Schmezer P, Burkholder I, Waas P, Boffetta P, Brennan P, et al. Polymorphisms in three base excision repair genes and breast cancer risk in Thai women. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2008;111(2):279–88.

Osorio A, Milne RL, Kuchenbaecker K, Vaclova T, Pita G, Alonso R, et al. DNA glycosylases involved in base excision repair may be associated with cancer risk in BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutation carriers. PLoS Genet. 2014;10(4):e1004256.

Kim KY, Han W, Noh DY, Kang D, Kwack K. Impact of genetic polymorphisms in base excision repair genes on the risk of breast cancer in a Korean population. Gene. 2013;532(2):192–6.

Flesch-Janys D, Slanger T, Mutschelknauss E, Kropp S, Obi N, Vettorazzi E, et al. Risk of different histological types of postmenopausal breast cancer by type and regimen of menopausal hormone therapy. Int J Cancer. 2008;123(4):933–41.

Darby S, McGale P, Correa C, Taylor C, Arriagada R, Clarke M, et al. Effect of radiotherapy after breast-conserving surgery on 10-year recurrence and 15-year breast cancer death: meta-analysis of individual patient data for 10,801 women in 17 randomised trials. Lancet. 2011;378(9804):1707–16.

Buck K, Vrieling A, Zaineddin AK, Becker S, Husing A, Kaaks R, et al. Serum enterolactone and prognosis of postmenopausal breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29(28):3730–8.

Seibold P, Hall P, Schoof N, Nevanlinna H, Heikkinen T, Benner A, et al. Polymorphisms in oxidative stress-related genes and mortality in breast cancer patients--potential differential effects by radiotherapy? Breast. 2013;22(5):817–23.

Seibold P, Hein R, Schmezer P, Hall P, Liu J, Dahmen N, et al. Polymorphisms in oxidative stress-related genes and postmenopausal breast cancer risk. Int J Cancer. 2011;129(6):1467–76.

Michailidou K, Hall P, Gonzalez-Neira A, Ghoussaini M, Dennis J, Milne RL, et al. Large-scale genotyping identifies 41 new loci associated with breast cancer risk. Nat Genet. 2013;45(4):353–61. 61e1-2.

Abecasis GR, Auton A, Brooks LD, DePristo MA, Durbin RM, Handsaker RE, et al. An integrated map of genetic variation from 1,092 human genomes. Nature. 2012;491(7422):56–65.

Howie B, Fuchsberger C, Stephens M, Marchini J, Abecasis GR. Fast and accurate genotype imputation in genome-wide association studies through pre-phasing. Nat Genet. 2012;44(8):955–9.

DerSimonian R, Laird N. Meta-analysis in clinical trials. Control Clin Trials. 1986;7(3):177–88.

Higgins JP, Thompson SG. Quantifying heterogeneity in a meta-analysis. Stat Med. 2002;21(11):1539–58.

Bieche I, Pennaneach V, Driouch K, Vacher S, Zaremba T, Susini A, et al. Variations in the mRNA expression of poly (ADP-ribose) polymerases, poly (ADP-ribose) glycohydrolase and ADP-ribosylhydrolase 3 in breast tumors and impact on clinical outcome. Int J Cancer. 2013;133(12):2791–800.

Santarpia L, Iwamoto T, Di Leo A, Hayashi N, Bottai G, Stampfer M, et al. DNA repair gene patterns as prognostic and predictive factors in molecular breast cancer subtypes. Oncologist. 2013;18(10):1063–73.

Bruun GH, Doktor TK, Andresen BS. A synonymous polymorphic variation in ACADM exon 11 affects splicing efficiency and may affect fatty acid oxidation. Mol Genet Metab. 2013;110(1–2):122–8.

Hull J, Campino S, Rowlands K, Chan MS, Copley RR, Taylor MS, et al. Identification of common genetic variation that modulates alternative splicing. PLoS Genet. 2007;3(6):e99.

Yelamos J, Schreiber V, Dantzer F. Toward specific functions of poly (ADP-ribose) polymerase-2. Trends Mol Med. 2008;14(4):169–78.

Lupo B, Trusolino L. Inhibition of poly (ADP-ribosyl) ation in cancer: old and new paradigms revisited. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2014;1846(1):201–15.

Shen Y, Aoyagi-Scharber M, Wang B. Trapping poly (ADP-ribose) polymerase. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2015;353(3):446–57.

Filippini SE, Vega A. Breast cancer genes: beyond BRCA1 and BRCA2. Front Biosci (Landmark Ed). 2013;18:1358–72.

Albarakati N, Abdel-Fatah TM, Doherty R, Russell R, Agarwal D, Moseley P, et al. Targeting BRCA1-BER deficient breast cancer by ATM or DNA-PKcs blockade either alone or in combination with cisplatin for personalized therapy. Mol Oncol. 2014;9(1):204–17.

Beck C, Robert I, Reina-San-Martin B, Schreiber V, Dantzer F. Poly (ADP-ribose) polymerases in double-strand break repair: Focus on PARP1, PARP2 and PARP3. Exp Cell Res. 2014;329(1):18–25.

Bewick MA, Conlon MS, Lafrenie RM. Haplotypes of XRCC1 and survival outcome in patients with metastatic breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2009;117(3):667–9.

Jaremko M, Justenhoven C, Schroth W, Abraham BK, Fritz P, Vollmert C, et al. Polymorphism of the DNA repair enzyme XRCC1 is associated with treatment prediction in anthracycline and cyclophosphamide/methotrexate/5-fluorouracil-based chemotherapy of patients with primary invasive breast cancer. Pharmacogenet Genomics. 2007;17(7):529–38.

Tengstrom M, Mannermaa A, Kosma VM, Hirvonen A, Kataja V. XRCC1 rs25487 polymorphism predicts the survival of patients after postoperative radiotherapy and adjuvant chemotherapy for breast cancer. Anticancer Res. 2014;34(6):3031–7.

Acknowledgement

We thank all the individuals who took part in these studies and all the researchers, clinicians, technicians and administrative staff who have enabled this work to be carried out. In particular, we thank Ursula Eilber, Christina Krieg and Muhabbet Celik for excellent technical assistance in the MARIE study and M. Schick and R. Fischer from the DKFZ Genomics and Proteomics Core Facilities for their support during Illumina genotyping. This study would not have been possible without the contributions of the following: Joe Dennis, Alison M. Dunning, Andrew Lee, and Ed Dicks, Craig Luccarini and the staff of the Centre for Genetic Epidemiology Laboratory, Javier Benitez, Anna Gonzalez-Neira and the staff of the CNIO genotyping unit, Jacques Simard and Daniel C. Tessier, Francois Bacot, Daniel Vincent, Sylvie LaBoissière and Frederic Robidoux and the staff of the McGill University and Génome Québec Innovation Centre, Stig E. Bojesen, Sune F. Nielsen, Borge G. Nordestgaard, and the staff of the Copenhagen DNA laboratory, and Julie M. Cunningham, Sharon A. Windebank, Christopher A. Hilker, Jeffrey Meyer and the staff of Mayo Clinic Genotyping Core Facility. RBCS thank Petra Bos, Jannet Blom, Ellen Crepin, Anja Nieuwlaat, Annette Heemskerk, the Erasmus MC Family Cancer Clinic.

The MARIE study was supported by the Deutsche Krebshilfe e.V. (70-2892-BR I, 106332, 108253, 108419), the Hamburg Cancer Society, the German Cancer Research Center, the Federal Ministry of Education and Research (BMBF) Germany (01KH0402) and the Dietmar Hopp Stiftung (23017006). Funding for the iCOGS infrastructure came from: the European Community’s Seventh Framework Programme under grant agreement n° 223175 (HEALTH-F2-2009-223175) (COGS), Cancer Research UK (C1287/A10118, C1287/A10710, C490/A10119, C490/A16561), the National Institutes of Health (CA128978, CA076016) and Post-Cancer GWAS initiative (No. 1 U19 CA148537 - the GAME-ON initiative), the Department of Defence (W81XWH-10-1-0341), the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR) for the CIHR Team in Familial Risks of Breast Cancer, Komen Foundation for the Cure, the Breast Cancer Research Foundation, and the Ovarian Cancer Research Fund. The HEBCS study was funded by the Helsinki University Central Hospital Research Fund, the Academy of Finland (132473), the Sigrid Juselius Foundation, the Finnish Cancer Society and the Nordic Cancer Union. Financial support for KARBAC was provided through the regional agreement on medical training and clinical research (ALF) between Stockholm County Council and Karolinska Institutet, the Swedish Cancer Society, The Gustav V Jubilee foundation and Bert von Kantzows foundation. The KBCP was financially supported by the special Government Funding (EVO) of Kuopio University Hospital grants, Cancer Fund of North Savo, the Finnish Cancer Organizations, the Academy of Finland and by the strategic funding of the University of Eastern Finland. LMBC is supported by the ‘Stichting tegen Kanker’ (232–2008 and 196–2010). Diether Lambrechts is supported by the FWO and the KULPFV/10/016-SymBioSysII. The NBCS was supported by the K.G. Jebsen Centre for Breast Cancer Research; the Research Council of Norway grant 193387/V50 (to A-L Børresen-Dale and V.N. Kristensen) and grant 193387/H10 (to A-L Børresen-Dale and V.N. Kristensen), South Eastern Norway Health Authority (grant 39346 to A-L Børresen-Dale) and the Norwegian Cancer Society (to A-L Børresen-Dale and V.N. Kristensen). The RBCS was funded by the Dutch Cancer Society (DDHK 2004–3124, DDHK 2009–4318). The SASBAC study was supported by funding from the Agency for Science, Technology and Research of Singapore (A*STAR), the US National Institute of Health (NIH) and the Susan G. Komen Breast Cancer Foundation. SEARCH is funded Cancer Research UK and Breast Cancer Campaign (C490/A10124, 2009MayPR42) and supported by the UK National Institute for Health Research Biomedical Research Centre at the University of Cambridge. SKKDKFZS is supported by the German Cancer Research Center (DKFZ).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

Conceived and designed the study: OP, PSc, JCC. Analysed the data: PS, SB, JCC. Acquisition of data and providing data: KA, CB, ALBD, MKB, FJC, AMD, DFJ, RF, GGA, AH, JMH, KH, MJH, PH, UH, AJ, MK, VK, VMK, VKr, DL, JL, JLiu, AM, KM, SM, HN, SN, KSP, PP, VR, CS, JMS, MS, MKS, DT, HUU, HW, QW. Drafted the manuscript: PS, JCC, OP. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Jenny Chang-Claude and Odilia Popanda shared seniors authorship.

Additional files

Additional file 1: Figure S1.

Flowchart on sample size for the studies in BCAC used for the replication analysis. (DOCX 16 kb)

Additional file 2: Table S1.

Description of the BCAC studies included in this analysis.(DOCX 25 kb)

Additional file 3: Figure S2.

Meta-analysis across BCAC studies of PARP2 and breast cancer prognosis. Forest plot of the combined hazard ratios and 95 % confidence intervals for PARP2 rs878156 in the discovery MARIE study and the replication studies in Breast Cancer Association Consortium (BCAC) using fixed effect models, according to treatment, i.e. no chemotherapy (A), any type of chemotherapy (B), and anthracycline-based chemotherapy (C). The combined effects for the BCAC studies were also based on fixed effect models. (DOCX 996 kb)

Additional file 4: Figure S3.

Meta-analysis across BCAC studies of XRCC1 and breast cancer prognosis. Forest plot of the combined hazard ratios and 95 % confidence intervals for XRCC1 rs3213356 in the discovery MARIE study and the replication studies in Breast Cancer Association Consortium (BCAC) using fixed effect models, according to treatment, i.e. no chemotherapy (A), any type of chemotherapy (B), and anthracycline-based chemotherapy (C). The combined effects for the BCAC studies were also based on fixed effect models. (DOCX 1077 kb)

Additional file 5: Table S2.

Associations between SNP and breast cancer-specific mortality by radiotherapy for interactions showing p <0.1 (LRT)$ in the MARIE study and results of replication in BCAC studies. (DOCX 20 kb)

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Seibold, P., Schmezer, P., Behrens, S. et al. A polymorphism in the base excision repair gene PARP2 is associated with differential prognosis by chemotherapy among postmenopausal breast cancer patients. BMC Cancer 15, 978 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12885-015-1957-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12885-015-1957-7