Abstract

Background

Despite the extensive research on fertility desires among women the world over, there is a relative dearth of literature on the desire for more children in sub-Saharan Africa (SSA). This study, therefore, examined the desire for more children and its predictors among childbearing women in SSA.

Methods

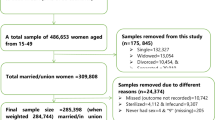

We pooled data from 32 sub-Saharan African countries’ Demographic and Health Surveys. A total of 232,784 married and cohabiting women with birth history, who had complete information on desire for more children made up the sample for the study. The outcome variable for the study was desire for more children. Multilevel logistic regression analysis was conducted. Results were presented using adjusted odds ratios (aOR), with their corresponding 95% confidence intervals (CI).

Results

The overall prevalence of the desire for more children was 64.95%, ranging from 34.9% in South Africa to 89.43% in Niger. Results of the individual level predictors showed that women aged 45–49 [AOR = 0.04, CI = 0.03–0.05], those with higher education [AOR = 0.80, CI = 0.74–0.87], those whose partners had higher education [AOR = 0.88; CI = 0.83–0.94], women with four or more births [AOR = 0.10, CI = 0.09–0.11], those who were using contraceptives [AOR = 0.68, CI = 0.66–0.70] and those who had four or more living children [AOR = 0.09 CI = 0.07–0.12] were less likely to desire for more children. On the other hand, the odds of desire for more children was high among women who considered six or more children as the ideal number of children [AOR = 16.74, CI = 16.06–17.45] and women who did not take decisions alone [AOR = 1.58, CI = 1.51–1.65]. With the contextual factors, the odds of desire for more children was high among women who lived in rural areas compared to urban areas [AOR = 1.07, CI = 1.04–1.13].

Conclusions

This study found relatively high prevalence of women desiring more children. The factors associated with desire for more children are age, educational level, partners’ education, parity, current contraceptive use, ideal number of children, decision-making capacity, number of living children and place of residence. Specific public health interventions on fertility control and those aiming to design and/or strengthen existing fertility programs in SSA ought to critically consider these factors.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

It is estimated that, out of the 78 million added to the world population annually, about 97% originate from low- and middle-income countries [1]. Couples are having fewer children in recent times, and this may have led to a decrease in population growth in most high-income countries [2]. However, demographers seem to have concerns about the pattern of demographic development in low- and middle-income countries, due to the fact that, on the average Africans give 34 births per 1000 population, with a total fertility rate of 4.5 [3]. Countries in sub-Saharan African (SSA) account for more than 50% of global fertility [4]. Evidently, the Population Reference Bureau [3] estimates the fertility rate of SSA at 4.8, which is twice the global rate of 2.4.

Couples are able to achieve their fertility desires and pregnancy spacing by using modern contraceptives [5]. However, contraceptive use and other family planning strategies are considered to be low in SSA, and this has increased mistimed and unwanted pregnancies, as well as high youth dependency [6,7,8]. This reveals that desire for more children is of great concern for women in their reproductive ages in SSA [2]. It is estimated that, in SSA, contraceptive use among women in union is below 22%, compared with 86% in East Asia and 72% in Latin America and the Caribbean [9]. It has also been revealed that, in parts of SSA, more than 50% of women with four or more children still desire to have more children [10].

Deeply rooted in strong societal and personal factors [2, 11,12,13,14], desire for children is pivotal to family formation process in several communities of the world. Desire for more children is greatly driven by preference for large families, desire for sons, and the union’s stability [15,16,17]. A Demographic and Health Survey (DHS) based study observed that women in their reproductive ages in about sixty countries desired more children, particularly in Western and Middle Africa between 1998 and 2008; however, these women had an average of six children [10].

Theoretically, this work is situated within the demand-supply framework on fertility by Easterlin [18]. The framework has been applied to study fertility desire and intentions in various parts of the world. It posits that fertility desire(s) are influenced by both demand and supply factors. In the model, ‘Demand’ refers to the family size and composition a couple would have under ideal circumstances [18]. Its dimensions include the number of children, sex, and desirable spacing of surviving children, and these are influenced by the couple's personal preferences, the influence from community as well as the socio-cultural norms [18,19,20]. Supply, on the other hand, refers to the number of children the couples are able to bring forth. Based on these, a couple or woman will desire more children if they/she feel(s) that children are valuable and will serve as assets to them in the society in which they find themselves and vice-versa [18]. Those who do not desire more children may adopt various mechanisms to reduce childbirth, including contraceptive usage [21].

Bongaarts [22] provides an alternative implementation of the demand-supply framework for determining fertility proposed by Easterlin. The objective of Bongaarts framework was to simplify its application by changing some key features, while maintaining the original conceptual structure largely intact. Bongaarts proposed that fertility is a function of three determinants (supply of births, demand for births, and degree of preference implementation). Supply of births is measured as natural total fertility, which is the rate of childbearing that would prevail in the absence of deliberate efforts by couples to limit family size. Demand for births is measured as wanted total fertility, which refers to the rate of childbearing that would be achieved if all women were able to eliminate unwanted births. Degree of preference implementation is the net result of a decision-making process in which couples weigh the cost of fertility regulation and the cost of unwanted childbearing [22].

Majority of studies on fertility desire over the world have adopted a country-specific focus, paying attention to Nigeria [23], Iran [24], Nepal [25], and Uganda [2], with a few focusing on broader geographical areas such as East Africa [26], and Nigeria and Ghana [12]. Despite this extensive research, there is a relative paucity of literature on the fertility desires in SSA, as most countries in SSA are yet to feature in studies of this kind. The present study attempts to fill this gap by assessing the prevalence of desire for more children and its determinants among childbearing women in 32 countries in SSA.

Methods

Study design

We pooled data from the DHS of 32 sub-Saharan African countries. Specifically, we used data from the women’s file of the various countries. The DHS focuses on essential maternal and child health markers, including fertility preference [27]. The DHS employs a two-stage stratified sampling technique, which makes the survey data nationally representative [28]. A total of 232,784 married and cohabiting women with birth history who had complete information on desire for more children made up the sample for the study. Details of the methodology adopted by the DHS have been reported elsewhere [28]. Table 1 gives a detailed description of the study sample.

Outcome variable

Desire for more children was the outcome variable. This was derived from the question “Would you like to have a (another) child with your husband/partner, or would you prefer not to have any more children with him?” It had five responses: “want a (another) child,” “want no more,” “cannot get pregnant,” “undecided,” and “don’t know.” Our outcome variable was computed from two of these responses, namely “want a (another) child,” coded as 1 and “want no more,” coded as 0. Hence, women who responded that they want another child were considered as having a desire for more children while those who responded that they want no more were considered as not having a desire for more children. Women who provided any other response (“cannot get pregnant,” “undecided,” and “don’t know”) were excluded because their responses were unclear about their fertility preference.

Independent variables

The study used eleven independent variables, grouped into individual level and contextual level factors. The individual level factors included age, highest educational level, partner’s highest educational level, parity, current use of contraceptives, exposure to media (radio, television and newspaper/magazine), ideal number of children, decision making autonomy (decision on healthcare, decision on large household purchase and decision on visits to family or relatives), and number of living children. The contextual level factors were place of residence and wealth status. These variables were considered because of their statistically significant relationships with desire for more children in previous studies [2, 29, 30]. Details of how each of these variables were coded can be found in Table 2. Based on the findings of previous studies [2, 12, 21,22,23,24,25,26], we hypothesized that older women would be less likely to desire for more children compared to younger women; women with higher levels of education would be less likely to desire for more children compared to those with no formal education; women whose partners have higher levels of education would have lower odds of desiring for more children compared to those whose partners have no formal education. Other hypotheses that guided the analysis and results of the study were that the odds of desire for more children would decrease with increasing parity, wealth quintile, higher number of living children, contraceptive use and exposure to media. Women who consider 6 + as the ideal number of children, those who do not take decisions alone, and those who live in rural areas would be more likely to desire for more children.

Statistical analyses

Stata version 14.0 was used to process and analyse the data. The analysis began with a computation of the prevalence of desire for more children in SSA using bar chart. After this, we pooled the datasets and calculated the proportions of desire for more children for each of the explanatory variables. We then used a bivariate logistic regression to assess the association between the explanatory variables and desire for more children. This was done to identify significant explanatory variables for the next part of the analysis, which involved multilevel logistic regression. For the multilevel logistic regression, a two-stage approach was employed, where women were nested within clusters and clusters were considered as random effects to cater for the unexplained variability at the contextual level [31]. Four models were generated from the multilevel modelling, consisting of the empty model (Model 0), Model I, Model II, and Model III. Model 0 showed the variance in desire for more children attributed to the distribution of the primary sampling units (PSUs) in the absence of the explanatory variables. Model I had the individual level factors and desire for more children while Model II contained the contextual level factors and desire for more children. The final model (Model III) was the complete model that had the individual and contextual level factors and desire for more children. Model comparison was done using the log-likelihood ratio (LLR) and Akaike’s Information Criterion (AIC) tests. Odds ratio and associated 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were presented for all the models apart from Model 0. To ensure non-existence of correlation between the significant explanatory variables, we ran a multicollinearity test, using the variance inflation factor (VIF), and the results showed no evidence of collinearity among the explanatory variables (Mean VIF = 1.71, Maximum VIF = 2.93 and Minimum VIF = 1.03). Statistical significance was declared at p < 0.05. Sample weight (v005/1,000,000) was applied to correct for over- and under-sampling while the SVY command was used to account for the complex survey design and generalizability of the findings. According to Hatt and Waters [32], pooling data can reveal broader results that are ‘‘often obscured by the noise of individual data sets.’’ To calculate the pooled values, an additional adjustment is needed to account for the variability in the number of individuals sampled in each country. This is accomplished using the weighting factor 1/(A*nc/nt), where A is the number of countries asked a particular question, nc is the number of respondents for the country c, and nt is the total number of respondents over all countries asked the question [33].

Ethical approval

The DHSs obtained ethical clearance from the Ethics Committee of ORC Macro Inc. as well as Ethics Boards of partner organisations of the various countries such as the Ministries of Health. During each of the surveys, either written or verbal consent was provided by the women. This was a secondary analysis of data and, therefore, we did not need further approval for this study since the data is available in the public domain. However, we sought permission from MEASURE DHS website and access to the data was provided after our intent for the request was assessed and approved on 3rd April, 2019. Further information about the DHS data usage and ethical standards is available at http://goo.gl/ny8T6X

Results

The proportion of childbearing women who have desire for more children in SSA is presented in Fig. 1. The overall prevalence of the desire for more children was 64.95%, ranging from 34.9% in South Africa to 89.43% in Niger.

Bivariate analysis results on desire for more children across socio-demographic characteristics of childbearing women in SSA

The socio-demographic characteristics of the women who participated in the study are presented in Table 2. Table 2 further presents the proportion of women who desire for more children and the unadjusted odds results of the association between the socio-demographic characteristics and desire for more children. Desire for more children was high among women aged 15–19 (95.3%), those with no formal education (69.3%), those whose partners had no formal education (70.9%), women with one birth (94.4%), women who were not current contraceptive users (69.3%), and those who were not exposed to media (68.3%). High prevalence of desire for more children was also found among women who perceived six or more children as the ideal number of children (72.2%), those who do not take decisions alone (66.6%), those who had no living children (96.6%), women who lived in rural areas (66.6%), and poorest women. Results from the bivariate analysis showed that all the independent variables had statistically significant association with desire for more children (see Table 2).

Multilevel logistic regression results on the predictors of desire for more children among childbearing women in SSA

Table 3 presents results of the multilevel logistic regression analysis of the predictors of desire for children among married and cohabiting women in SSA. With the fixed effects results, results of the individual level predictors showed that women aged 45–49 [AOR = 0.04, CI = 0.03–0.05], those with higher education [AOR = 0.80, CI = 0.74–0.87], and those whose partners had higher education [AOR = 0.88; CI = 0.83–0.94] had lower odds to desire for more children, compared to women aged 15–19, those with no formal education, and those whose partners had no formal education, respectively. Furthermore, the likelihood of desire for more children decreased among women with four or more births [AOR = 0.10, CI = 0.09–0.11], those who were using contraceptives [AOR = 0.68, CI = 0.66–0.70], and those who had four or more living children [AOR = 0.09 CI = 0.07–0.12], compared to those with one child, those who were not using contraceptives, and those who had no living children, respectively. On the other hand, the odds of desire for more children was high among women who considered six or more children as the ideal number of children [AOR = 16.74, CI = 16.06–17.45] and women who did not take decisions alone [AOR = 1.58, CI = 1.51–1.65], compared to those who consider 0–3 children as the ideal number of children and those who took decisions alone, respectively (see Table 3, Model III). With the contextual factors, the odds of desire for more children was high among women who lived in rural areas compared to urban areas [AOR = 1.07, CI = 1.04–1.13].

In terms of the random effects results, in the empty model, there were substantial variations in the likelihood of desire for more children across the clustering of the PSUs (σ2 = 0.03, 95% CI 0.02–0.04). The empty model showed that 3% of the total variance in desire for more children was attributed to between-cluster variation of characteristics (ICC = 0.03). The between-cluster variations showed a decrease from 3–2% from the empty model to the individual-level only model (Model I). From Model I, the ICC increased to 3% (ICC = 0.03) in the contextual level only model but decreased to 2% in the complete model (Model III), which had both the individual and contextual level factors. This explains that the variations in the likelihood of desire for more children could be attributed to the differences in the contextual level factors (see Table 3, Model III).

Discussion

This study sought to assess the prevalence of desire for more children and its determinants among 232,784 childbearing women in SSA underpinned by the demand-supply framework on fertility by Easterlin [18]. The study found that 64.95% of women desired more children, and this ranged from 34.9% in South Africa to 89.34% in Niger. This finding is comparable to previous studies [34, 35]. However, it is higher than what was found in other studies [36,37,38]. The possible pathways to explain the differences in the study findings could be differences in study scope and setting, the population sample, and the time these studies were carried out. The higher prevalence of desire for more children recorded in this study could also be attributed to the general importance attached to more children in most parts of SSA [34, 35, 39].

We also observed from this current study that increase in wealth status and educational level of both women and their partners is likely to reduce women’s desire for more children. In addition, women who are working are less likely to desire more children. These findings corroborate several previous studies which have revealed that higher socioeconomic status is associated with lower fertility desires [34, 40,41,42,43,44]. This result can be discussed within the context of the wealth flow hypotheses postulated by Caldwell [45, 46], who elucidates that, in contemporary societies, women and families who are in the high socioeconomic strata tend to view more children as additional burden that has the tendency to strain their resources, including time. On the other hand, women in the low socioeconomic strata might wish to give birth to more children, as they see it as a rational economic decision since they consider each child as an additional asset for security in their old age. Additionally, due to the various economic activities of those in high socioeconomic strata, they might not have more children, as opposed to those who are in the low socioeconomic status who might be into farming activities and consider children as a source of labour for their farming activities.

Channon and Harper [47] also espoused that, in contemporary era, women have competing life goals and this usually translates into less demand for children [17]. They maintained that, for highly educated women, it is sometimes problematic for them to combine many children and life goals such as occupying certain managerial position that will not allow certain amount of maternity leave within a given period. Rabbi [48] also explained that highly educated mothers might be exposed to the various disadvantages associated with high fertility. Similarly, employed mothers always seek for less number of children, as it becomes harder for them to take good care of their children after maintaining the job [48, 49]. The study also showed that women who are in the rural areas are more likely to desire for more children, compared to women in urban areas. This is consistent with what was reported in the context of Bangladesh [48].

Furthermore, the study showed an inverse relationship between age and parity, on the one hand, and desire for more children, on the other hand. Specifically, as parity and age increases, the less likely it is for women to indicate that they desire for more children. This is similar with several previous studies in countries such as China [50] and Sri Lanka [51]. Relatedly, it was found that women who use contraceptives are less likely to desire more children. This corroborates previous studies [39, 52,53,54]. The probable explanation is that women who are using contraceptives might not wish to give birth to additional children and would adopt various mechanisms to achieve this goal, including the use of contraceptives.

Moreover, it was found that access to mass media is associated with desire for more children. Specifically, women who are exposed to television have lower odds of desiring more children. This finding corroborates previous studies on the association between mass media and fertility behaviours such as small family size [39, 48, 55, 56]. Rabbi [48] explained that messages obtained from television possess a greatest impact on the propensity for people to use family planning methods and also limit the number of children they wish to have, since they can see how beautiful small families are shown on television adverts.

We noted that women having at least six ideal number of children had higher odds of desiring for more children. Having desire for six or more children signifies high demand as espoused by the supply and demand framework [18]. Women with this desire may be of the conviction that they have the reproductive capacity to give birth to the desired higher number “supply”. These women may have a number of rewards for having more children. Among the possibilities to explain this involves the thought that children are assets, gains, or security [57]. Couples with underlying medical conditions such as sickle cells may also be inspired to have more children due to fear of losing some of the children to untimely death [58].

Women without solo decision-making capacity had higher likelihood to desire more children. Being able to decide on matters pertaining to one’s life without any interference offers an opportunity for persons to exercise or implement their choices. Although fertility is declining on the whole [59], the findings of this study indicate that demand is likely to be high if fertility decisions are taken by women alone. The study, therefore, suggests the need for subsequent fertility control interventions to ensure male or partner involvement in fertility decisions. The study also revealed that women with four or more living children were less likely to desire more children. Women with four or more living children may be satisfied with their existing number of children.

Implications for fertility control

The findings from this study may be instructive to the current fertility control interventions and initiatives across SSA. The study has indicated the traits of women with desire for more children in SSA. Admittedly, nearly all countries in SSA have instituted measures to regulate fertility by moderating both demand and supply factors [60]. Our findings have provided evidence from current data sets that may aid in benchmarking parameters for evaluating and reviewing existing policies and interventions in order to render them more sensitive to the current population. To contextualise our findings and derive much benefit at the country level, governments of SSA and partner organisations should be sensitive to the in-country nuances driven by cultural, geographical, and socioeconomic factors. This may be beneficial in ensuring that the number of children desired by women falls within national estimations and expectations.

Strengths and limitations of the study

The use of nationally representative datasets of 32 countries in SSA and the multi-stage sampling technique to select the respondents is a major strength of this study. These make it feasible to generalise the findings to all women in sexual unions in SSA. The relatively large sample size also aided in fitting robust logistic regression models to model the factors associated with desire for more children while controlling for confounders. Despite these strengths, it is impossible to establish temporality of sequence, and the possibility of social desirability biases cannot be overruled.

Conclusion

This study found a relatively high prevalence of women desiring more children. The factors associated with desire for more children are age, educational level, partners’ education, parity, current contraceptive use, ideal number of children, decision-making capacity, number of living children and place of residence. Specific public health interventions on fertility control and those aiming to design and/or strengthen existing fertility programs in SSA ought to critically consider these factors.

Availability of data and materials

The dataset is available freely for download at: https://dhsprogram.com/data/available-datasets.cfm.

Abbreviations

- cOR:

-

crude Odds Ratio

- aOR:

-

Adjusted Odds Ratio

- CI:

-

Confidence Interval

- SSA:

-

Sub-Saharan Africa

- DHS:

-

Demographic and Health Surveys

References

Aziz Ali S, Khuwaja N. Determinants of unintended pregnancy among women of reproductive age in developing countries: A narrative review. Journal of Midwifery Reproductive Health. 2016;4(1):513–21.

Matovu JKB, Makumbi F, Wanyenze RK, Serwadda D. Determinants of fertility desire among married or cohabiting individuals in Rakai, Uganda: a cross-sectional study. Reproductive Health. 2017;14(2):2–11.

Population Reference Bureau. World Population Data Sheet. 2019.

Guengant JP, May JF. L’Afrique subsaharienne dans la démographie mondiale. Études. 2011;415(10):305–16.

Prata N. Making family planning accessible in resource-poor settings. Philos Trans R Soc Lond Biol Sci. 2009;3(64):3093–9.

Amalba A, Mogre V, Appiah MN, Mumuni WA. Awareness, use and associated factors of emergency contraceptive pills among women of reproductive age (15–49 years) in tamale, Ghana. BMC Womens Health. 2014. https://doi.org/10.1186/1472-6874-14-114.

Apanga PA, Adam MA. Factors influencing the uptake of family planning services in the Talensi District, Ghana. Pan Afr Med J. 2015. https://doi.org/10.11604/pamj.2015.20.10.5301.

Canning D, Raja S, Yazbeck AS. Africa’s demographic transition: dividend or disaster? https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/handle/10986/22036. Accessed 05 Dec 2018.

World Bank eFertility rate, total (births per woman). https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SP.DYN.TFRT.IN. Accessed 05 Dec 2018.

Westoff CF. Desired number of children: 2000–2008. DHS Comparative Reports No. 25. Calverton: ICF Macro; 2010. http://dhsprogram.com/pubs/pdf/CR25/CR25.pdf. Accessed 7 July 2016.

CIA. Country comparison: total fertility rate. The world fact book by the Central Intelligence Agency. Available at http://www.cia.gov/library/publications/the-worldfactbook/rankorder/2127rank.html. 2011.

Yaya OS, Osanyintupin OD, Akintande OJ. Determinants of Desired and Actual Number of Children and the Risk of having more than Two Children in Ghana and Nigeria. African Journal of Applied Statistics. 2018;5(2):403–18.

Chauduri S. The desire for sons and excess fertility: a household-level analysis of parit progression in India. Int Perspect Sex Reprod Health. 2012;38(4):178–86.

Creanga AA, Gillespie D, Karklins S, Tsui AO. Low use of contraception among poor women in Africa: an equity issue. Bull World Health Organ. 2011;89(4):258–66.

Dyer SJ, Abrahams N, Hoffman M, van der Spuy ZM. ‘Men leave me as I cannot have children’: women’s experiences with involuntary childlessness. Hum Reprod. 2002;17(6):1663–8.

Ngure K, Baeten JM, Mugo N, Curran K, Vusha S, Heffron R, Celum C, Shell-Duncan B. My intention was a child but I was very afraid: fertility intentions and HIV risk perceptions among HIV-serodiscordant couples experiencing pregnancy in Kenya. AIDS Care. 2014;26(10):1283–7.

Withers M, Kano M, Pinatih GN. Desire for more children, contraceptive use and unmet need for family planning in a remote area of Bali, Indonesia. Journal of Biosocial Science:2010:42(4):549.

Easterlin RA. An economic framework for fertility analysis. Stud Fam Plann. 1975;6(3):54–63.

Bulatao R, Lee R. An overview of fertility determinants in developing countries. In: Bulatao R, Lee R, editors. Determinants of Fertility in Developing Countries. Vol. 2. London: Fertility Regulation and Institutional Influences. Academic Press; 1983. p. 2.

Heer DM. Infant and child mortality and the demand for children. In: Bulatao R, Lee R, editors. Determinants of Fertility in Developing Countries. Supply and Demand for Children. London: Academic Press; 1983. p. 1.

Schoemaker J. Contraceptive use among the poor in Indonesia. International Family Planning Perspectives:2005:31(3):106–114.

Bongaarts J. The supply-demand framework for the determinants of fertility: An alternative implementation. Population studies. 1993 Nov 1;47(3):437 – 56.

Oyefabi A, Adelekan B, Nmadu AG, Abdullahi KM. Determinants of Desire for Child spacing among Women attending a Family Planning Clinic in Kaduna, North Western Nigeria. Journal of Community medicine primary health care. 2019;31(1):48–56.

Bagheri A, Saadati M. Factors Affecting the Demand for a Third Child among Iranian Women. Journal of Midwifery Reproductive Health. 2019;7(1):1536–43. DOI:https://doi.org/10.22038/jmrh.2018.25186.1275.

Shrestha N, Pokharel R, Poudyal A, Subedi R, Mahato NK, Gautam N, Dhungana GP. Fertility Desire and Its Determinants Among People Living with HIV in Antiretroviral Therapy Clinic of Teku Hospital, Nepal. HIV/AIDS – Research Palliative Care. 2020;12:41–6.

Muhoza DN, Broekhuis A, Hooimeijer P. Variations in Desired Family Size and Excess Fertility in East Africa. International Journal of Population Research. 2014.

Corsi DJ, Neuman M, Finlay JE, Subramanian SV. Demographic and health surveys: a profile. Int J Epidemiol. 2012;41(6):1602–13.

Aliaga A, Ren R. Optimal sample sizes for two-stage cluster sampling in demographic and health surveys. Demographics and Health Research/ 2006;30.

Atake EH, Ali PG. Women’s empowerment and fertility preferences in high fertility countries in Sub-Saharan Africa. BMC Womens Health. 2019;19(1):54.

Kodzi IA, Casterline JB, Aglobitse P. The time dynamics of individual fertility preferences among rural Ghanaian women. Stud Fam Plann. 2010;41(1):45–54.

Solanke BL, Oyinlola FF, Oyeleye OJ, Ilesanmi BB. Maternal and community factors associated with unmet contraceptive need among childbearing women in Northern Nigeria. Contraception Reproductive Medicine. 2019;4(1):11.

Hatt LE, Waters HR. Determinants of child morbidity in Latin America: a pooled analysis of interactions between parental education and economic status. Soc Sci Med. 2006;62(2):375–86.

Peng YK, Hight-Laukaran V, Peterson AE, Perez-Escamilla R. Maternal nutritional status is inversely associated with lactational amenorrhea in Sub-Saharan Africa: results from demographic and health surveys II and III. The Journal of Nutrition:1998:128(10):1672–80.

Götmark F, Andersson M. Human fertility in relation to education, economy, religion, contraception, and family planning programs. BMC Public Health. 2020;20(1):1–17.

Mathur S, Zhong X, Lutalo T, Wunder K, Wei Y, Wawer M, Santelli JS. ART availability and fertility desire: evidence from a population-based cohort in Rakai, Uganda from 2001–2011. San Diego: Paper presented at the 2015 Population Association of America Meeting; 2015.

Gutin SA, Namusoke F, Shade SB, Mirembe F. Fertility desires and intentions among HIV-positive women during the post-natal period in Uganda. Afr J Reprod Health. 2014;18(3):67–77.

Negash S, Yusuf L, Tefera M. Fertility desires predictors among people living with HIV/AIDS at art care centers of two teaching hospitals in Addis Ababa. Ethiop Med J. 2013;51(1):1–11.

Kawale P, Mindry D, Stramotas S, Chilikoh P, Phoya A, Henry K, Elashoff D, Jansen P, Hoffman R. Factors associated with desire for children among HIV-infected women and men: a quantitative and qualitative analysis from Malawi and implications for the delivery of safer conception counseling. AIDS Care. 2014;26(6):769–76.

Babalola S, Figueroa ME, Krenn S. Association of mass media communication with contraceptive use in Sub-Saharan Africa: a meta-analysis of Demographic and Health Surveys. Journal of health communication. 2017;22(11):885–95.

Akpa OM, Ikpotokin O. Modeling the determinants of fertility among women of childbearing age in Nigeria: Analysis using generalized linear modeling approach. International Journal of Humanities Social Science. 2012;2(18):106–7.

Samir KC, Lutz W. The human core of the shared socioeconomic pathways: Population scenarios by age, sex and level of education for all countries to 2100. Global Environmental Change. 2017;42:181–92.

Wang Q, Sun X. The role of socio-political and economic factors in fertility decline: a cross-country analysis. World Dev. 2016;87:360–70.

Wolf K, Mulder CH. Comparing the fertility of Ghanaian migrants in Europe with nonmigrants in Ghana. Population Space Place. 2019;25(2):e2171.

Withers M, Kano M, Pinatih GN. Desire for more children, contraceptive use and unmet need for family planning in a remote area of Bali, Indonesia. J Biosoc Sci. 2010 Jul;42(4):549–62.

Caldwell JC. Mass education as a determinant of the timing of fertility decline. Population and development review. 1980:225–255.

Caldwell JC. On net intergenerational wealth flows: an update. Population development review. 2005;31(4):721–40.

Channon MD, Harper S. Educational differentials in the realisation of fertility intentions: Is sub-Saharan Africa different? PloS one. 2019;14:7.

Rabbi AF. Mass media exposure and its impact on fertility: Current scenario of Bangladesh. Journal of Scientific Research. 2012;4(2):383.

Beguy D. Demographic Research Volume 20, Article 7, Pages 97–128 Published 13 February 2009.

Eklund L. Preference or aversion? Exploring fertility desires among China’s young urban elite. Intersections: Gender Sexuality in Asia the Pacific. 2016;39:1–16.

De Silva WI. Do fertility intentions and behaviour influence sterilization in Sri Lanka? Asia-Pacific population journal. 1992;7(4):41.

Gizachew Abdissa Bulto TAZTKB. Demand for long-acting and permanent contraceptive methods and associated factors among married women of the reproductive age group in Debre Markos town, North West Ethiopia. Women’s Health. 2014;14:1–12.

Islam AZ, Mondal MN, Khatun ML, Rahman MM, Islam MR, Mostofa MG, Hoque MN. Prevalence and determinants of contraceptive use among employed and unemployed women in Bangladesh. International Journal of MCH AIDS. 2016;5(2):92.

Adiri F, Ibrahim HI, Ajayi V, Sulayman HU, Yafeh AM, Ejembi CL. Fertility behaviour of men and women in three communities in Kaduna state, Nigeria. African Journal of Reproductive Health. 2010;14(3):97–105.

Ajaero CK, Odimegwu C, Ajaero ID, Nwachukwu CA. Access to mass media messages, and use of family planning in Nigeria: a spatio-demographic analysis from the 2013 DHS. BMC public health. 2016 Dec;16(1):427.

Rahman M, Curtis SL, Chakraborty N, Jamil K. Women’s television watching and reproductive health behavior in Bangladesh. SSM-population health. 2017;3:525–33.

Mbacké C. The persistence of high fertility in sub-Saharan Africa: a comment. Population and Development Review:2017:43:330–7.

Stone L. African Fertility is Right Where It Should Be. Institute for Family Studies.2018. Retrieved from https://ifstudies.org/blog/african-fertility-is-right-where-it-should-be.

Shapiro D, Hinde A. On the pace of fertility decline in sub-Saharan Africa. Demographic Research:2017:37:1327–38.

Aliyu AA. Family planning services in Africa: The successes and challenges. Family Planning:2018:69.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Measure DHS for access to Demographic Health Survey’s unrestricted survey data files, which is authorized to distribute, at no cost, for legitimate academic research.

Funding

The study did not receive any funding.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

BOA was involved in the conceptualization of the study, and conducted the statistical analysis. BOA, AS, EKA, EB, EKA, EA and SY drafted the manuscript. All authors revised the manuscript for quality, consistency and accuracy. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The DHS surveys obtain ethical clearance from the Ethics Committee of ORC Macro Inc. as well as Ethics Boards of partner organisations of the various countries such the Ministries of Health. During each of the surveys, either written or verbal consent was provided by the women. This was a secondary analysis of data and, therefore, we did not need further approval for this study since the data is available in the public domain. However, we sought permission from MEASURE DHS website and access to the data was provided after our intent for the request was assessed and approved on 3rd April, 2019. Further information about the DHS data usage and ethical standards is available at http://goo.gl/ny8T6X.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Ahinkorah, B.O., Seidu, AA., Armah-Ansah, E.K. et al. Drivers of desire for more children among childbearing women in sub-Saharan Africa: implications for fertility control. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 20, 778 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12884-020-03470-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12884-020-03470-1