Abstract

Background

Different diets during pregnancy might have an impact on the health, reflected in the birthweight of newborns. The consumption of fruits and vegetables during pregnancy and the relationship with newborn health status have been studied by several authors. However, these studies have shown inconsistent results. Purpose: We assessed whether certain foods were related to the risk of small for gestational age (SGA).

Methods

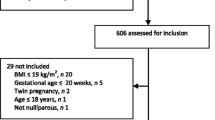

A matched by age (± 2 years) and hospital 1:1 case-control study of 518 pairs of pregnant Spanish women in five hospitals was conducted. The cases were women with an SGA newborn at delivery (neonates weighting less than the 10th percentile, adjusted for gestational age at delivery and sex, were diagnosed as SGA). The control group comprised women giving birth to babies adequate for gestational age (AGA). Mothers who gave birth to babies large for gestational age (LGA) were excluded. Data were gathered concerning demographic characteristics, socioeconomic status, toxic habits and diet. A food frequency questionnaire (FFQ) comprising 137 items was completed by all participants. The intake of vegetables, legumes and fruits was categorized in quintiles (Q1–Q5). Crude values and and adjusted odds ratios (AORs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were estimated using conditional logistic regression. The variables for adjustment were as follows: preeclampsia, education, smoking, weight gain per week during pregnancy, fish intake and previous preterm/low birthweight newborns.

Results

Total pulse intake showed an inverse association with the risk of SGA (trend p = 0.02). Women with an intake of fruits above 420 g/day (Q5), compared with women in Q1 (≤ 121 g/day) showed a decreased risk of SGA (AOR = 0.63, 95% CI = 0.40–0.98). The total consumption of vegetables was not associated with the risk of SGA. The intake of selenium was assessed: a protective association was observed for Q3–5; a daily intake above 60 μg was associated with a lower risk of SGA (AOR = 0.39, 95% CI: 0.22–0.69).

Conclusions

Fruits, pulses and selenium reduce the risk of SGA in Spanish women.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Small for gestational age (SGA) newborns are defined as those with a birthweight in the <10th percentile according to gestational age [1]. There are important adverse consequences for SGA newborns, including higher mortality and psychic, physical and social health problems in the short, medium and long term [2,3,4,5,6,7,8]. Between 5.3% and 23.7% of live newborns are SGA [2, 8,9,10].

Several risk factors for SGA have been identified. Among the non-dietary variables, the main factors are maternal education, income, smoking, body mass index (BMI), low weight gain during pregnancy, diseases during pregnancy (anaemia, preeclampsia, hypertension, infections, etc.), previous low birthweight and factors related to preterm delivery, inter alia [9,10,11,12,13,14,15]. In this regard, maternal diet may play an important role. Among others, it may have an “additional” role in various risks during pregnancy, such as gestational diabetes, maternal hypertension/preeclampsia, preterm birth and foetal growth restriction [16, 17].

The consumption of fruits and vegetables during pregnancy and the relationship with newborn health status has been studied by several authors [18,19,20]. Previous studies show inconsistent results. In the INfancia and Medio Ambiente (INfancy and Environment [INMA]) cohort study undertaken in Spain, incorporating 787 pregnant women with 11.5% SGA, a high intake of vegetables during pregnancy showed a lower incidence of SGA; no association was observed for fruit consumption [18]. In a cohort study in Denmark with 43,585 women) [19], the results contradicted those of the INMA cohort; that is, maternal consumption of fruit, but not vegetables, during pregnancy was associated with increased birthweight. A systematic review that did not include meta-analysis found no evidence that the intake of fruits and vegetables during pregnancy reduced the risk of having a SGA newborn [20].

The negative association of the consumption of fruits and vegetables with the risk of SGA can be explained by the high content of vitamins and micronutrients. Some studies have reported an inverse association of different vitamins (D, folic acid, etc.) and the risk of SGA [21, 22]. Several studies have analysed the relationship between selenium and newborn size, also with conflicting results [23,24,25,26,27]. Selenium has been implied to influence inflammation, oxidation and the proper functioning of the immunological system [28].

The intake of legumes is very common in Spain and other Mediterranean countries, as these are key elements of the Mediterranean diet. However, there are no published studies relating legume consumption to the risk of SGA. Given that previous studies correlating vegetable and fruit consumption with the risk of SGA present conflicting results, the aim of this study is to provide a fresh assessment of the effect of the intake of vegetables, legumes and fruits on the risk of SGA in a Southern European population.

Methods

The study population included women attending five hospitals in Eastern Andalusia (Spain): the University of Jaen Hospital (UJH), Ubeda Hospital (UB), the University of Granada Hospitals ([UGH] two centres) and Poniente Hospital (PH), serving 1.8 million people. Case and control groups were collected from 15 May 2012 to 15 July 2015.

Ethical approval was obtained from the Ethics Committees of the hospitals participating in the study: Comité de Ética de la Investigación del Complejo Hospitalario Universitario de Granada (Committee of Ethics of Investigation of the UGH), Comité de Ética de la Investigación del Hospital de Poniente (the Committee of Ethics of Investigation of the PH), Comité de Ética de la Investigación del Complejo Hospitalario Universitario de Jaén; (the Committee of Ethics of Investigation of the UJH) and Comité de Ética de la Investigación del Hospita de Úbeda (the Committee of Ethics of Investigation of the UB). Informed consent was obtained from the women participating in the study and we followed the protocols established by the respective health centres for accessing data from medical records to carry out this type of research with the purpose of publication/disclosure to the scientific community.

We estimated the appropriate sample size based on the results of a similar study [29]. To detect a significant (p < 0.05, odds ratio [OR] = 0.6) difference between extreme quintiles with a statistical power of 80%, we estimated that 447 pairs of cases and controls were required.

Cases

The eligibility criteria for cases were the delivery of a single live newborn diagnosed as small for gestational age (SGA) according to the tables developed for the Spanish population [30], without congenital malformations, during the study period and resident in the referral area of the hospital. Nineteen women declined participation. A total of 533 cases were selected: 79 (UJH), 369 (UGH), 46 (UB) and 39 (PH).

Controls

A pair of newborns matched by age at delivery (± 2 years) was selected within a week of inclusion of a case at the same hospital. Eligible women were those with a newborn of the appropriate gestational age meeting the same inclusion criteria for cases (residence in the referral area of the hospital and no malformations); women with large for gestational age (LGA) newborns were excluded. Sixty-five women declined participation.

Data collection

Data were gathered through personal interviews (conducted in the hospital by a specifically trained midwife within two days of delivery), clinical charts and prenatal care records. Information was obtained for the following variables: mother’s vital data (age at pregnancy, race, pre-pregnancy body mass index [BMI], educational level, marital status, income level and occupation), obstetric history (parity and abortions), previous adverse perinatal outcomes, conditions during pregnancy (infections, preeclampsia, diabetes and other obstetric conditions), birth weight (weight in grams in the delivery room), prescribed and over-the-counter drugs, smoking during pregnancy and prenatal care (number of visits and date of first visit, weight gain during pregnancy). Social class was coded according to five main levels (ranging from I [the highest] to V [the lowest]) based on the classification of the Spanish Society of Epidemiology [31], which is close to that of the Black Report [32]. Utilization of prenatal care was measured using the Kessner Index [33].

Alcohol consumption during and before pregnancy was assessed using a structured questionnaire in which the number and types of drinks on weekdays, weekends (including Friday evenings), and holidays (including the eve) were recorded.

Dietary assessment

The baseline questionnaire (Additional file 1) included a semiquantitative food frequency questionnaire, previously validated in Spain, comprising 137 items and open-ended questions to obtain information on use of dietary supplements [34]. The questionnaire was based on typical portion sizes and provided 9 options for the frequency of intake in the previous year for each food item (ranging from “never” or “almost never” to “≥ 6 times/day”). A dietician updated the nutrient data bank using the latest available information included in the food composition tables for Spain [35, 36]. After computing total energy intake, a total of 15 matched pairs were excluded because of unreliable dietary assessment (total energy intake > 4000 Kcal/day), leaving 518 pairs for analysis.

Statistical analysis

Food and nutrient intake were adjusted for total energy intake using the residuals method and separate regression models were performed to obtain the residuals [37]. Energy-adjusted food and nutrient intake were categorized in quintiles. It is recommended that selenium intake in pregnancy be at least 60 μg/day [38] and this cut-off level was also applied in the analysis of this micronutrient. Odds ratios (ORs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were estimated with conditional regression logistic models, with adjustments for potential confounders (adjusted ORs [aORs]): preeclampsia, education, smoking, weight gain per week during pregnancy, fish intake and previous preterm/low birthweight newborns. The addition of other variables (such as BMI) did not change the coefficients of the models appreciably (< 10% change). All p-values are 2-tailed. Statistical significance was set at p < 0.05. Analyses were performed in the Stata 14 program (College Station, TX).

Results

In all, 1036 women – 518 cases and 518 controls – participated in the study. The description of the study population is shown in Table 1. Maternal marital status influences the risk of SGA (p = 0.036). Well-known risk factors for SGA showed significant relationships in our study population, such as maternal smoking, previous low birth weight and/or preterm delivery, maternal BMI, low weight gain during pregnancy, preeclampsia and fish intake. The duration of gestation was shorter in the cases than in the controls and the frequency of Caesarean section was similar in both groups.

The relationship between legume intake and risk of SGA is shown in Table 2. In general, the highest levels of consumption are associated with a lower risk of SGA, although statistical significance is only achieved for kidney beans (aOR = 0.67, 95% CI: 0.48–0.94). The total amount of legumes was also analysed in quintiles. Significant p-values for the trend can be observed in both the crude and adjusted analyses: the higher the intake, the lower the risk.

Women with an intake of fruits > 420 g/day (Q5) compared with those with an intake ≤121 g/day (Q1) showed a decreased risk of SGA (aOR = 0.63, 95% CI = 0.40–0.98), although the trend was not significant (p for the trend = 0.136) (Table 3). Regarding the consumption of specific fruits, only melon (an intake of two or more times a week vs no consumption) yielded a significant relationship (aOR = 0.48, 95% CI = 0.29–0.78).

The consumption of dried fruits and nuts is displayed in Table 4. Total dried fruits showed a lower risk in Q5 (> 3.8 g/day) vs Q1 (< 0.1 g/day) in the crude analysis, although in multivariate analysis the association was borderline (aOR = 0.67, 95% CI: 0.42–1.05. Walnuts and other nuts did not exhibit any association with SGA.

No association was found between the total consumption of vegetables and the risk of SGA (Table 5). Regarding specific vegetables, significant associations were observed for asparagus, garlic and green beans, with borderline associations for eggplants, but not for the remaining vegetables. Finally, the consumption of selenium was assessed (Table 6): a protective association was observed for Q3–5. Given that the recommended daily intake is 60 μg, we found that an intake above this level was associated with a lower risk of SGA (aOR = 0.39, 95% CI: 0.22–0.69).

Discussion

The aim of this report was to assess the effect of the intake of vegetables, legumes and fruits on the risk of SGA in a Southern European population. According to our results, the overall consumption of legumes shows an inverse association with the frequency of SGA. The same holds for fruit consumption > 420 g/day. No relationship between the general consumption of vegetables and fruits and SGA was observed, nor for consumption of nuts. A protective association was observed with selenium intake above the recommended levels.

The consumption of fruits in the diet of pregnant women was studied in a case-control study in New Zealand comprising 844 cases (SGA) and 870 controls; it was reported that the insufficient consumption of fruit (intake < 0.75 servings of fruits a day) during pregnancy increased the risk of SGA [39]. Similar conclusions were obtained from a Danish cohort study [19] and an Indian prospective descriptive study carried out over two years [40]. In contrast, in the Spanish INMA cohort study [18], no such relationship was observed. We found an association for Q5 (> 420 g/day), although no significant trend was apparent. This association may be due to the high content of vitamins in fruits [41].

We did not find any significant relationship with dried fruits and nuts. These foods have interesting components in terms of reducing the risk of cardiovascular diseases [42] and they also have a high content of selenium. However, the amount ingested by women in our study was rather small: for Q5 consumption of dried fruits was > 3.8 g/day and of walnuts was > 5 g/day; this latter case implies a single unit per day.

The lack of a relationship between total vegetable intake and SGA in our study agrees with the conclusions of a systematic review [20]. In contrast, several studies have found that vegetable intake increases foetal size. The first of these is the INMA study [18], which reported a beneficial effect on foetal growth attributed by the authors to the high content of antioxidants and folic acid in vegetables. Two other reports, from Denmark [19] and India [40], noted the same results. These studies did not analyse specific types of vegetables and therefore it is not possible to compare our results for green beans, garlic and asparagus (in which protective associations with SGA risk were observed).

Insufficient consumption of selenium increases the frequency of pre-eclampsia, a clear risk factor for SGA [23]. An analysis on a subset (126 pregnant adolescent women) from a prospective observational study in London found low levels of selenium in women delivering an SGA newborn [24]. Sun et al., in a cross-sectional study carried out in 209 pregnant women from Eastern China, observed that an increase in selenium intake could reduce serum cadmium levels, improving foetal growth [25]. However, Horan et al., in a cohort analysis of 554 infants from the Randomised cOntrol trial of LOw glycaemic index diet to prevent macrosomia (ROLO) study (a randomized controlled trial conducted in Ireland of 800 secundigravid women with a previous macrosomic baby) showed that selenium was inversely related with the womb perimeter of newborns [26]. Also, in a Spanish study with a rather small sample size (n = 197 women), without data on SGA, no association was observed between selenium intake and newborn size [27].

Legumes, mainly lentils and chickpeas, have a high selenium content. In general, the content of selenium in most vegetables is low. The exception is garlic, which has 23 times the content of selenium of tomato or lettuce; also, green beans have almost three times the amount of selenium of other common vegetables [35, 36, 43]. In our results, both garlic and green beans reduced SGA risk. However, mushrooms, with a high selenium content, were unrelated to SGA risk in our population.

It would be very interesting to analyse whether diet can overcome the influence of obesity, malnutrition and other unfavourable conditions, such as low socioeconomic status and smoking. This can be addressed in future studies. Our sample had no statistical power to allow reliable analysis of these important variables; in our sample, obesity (BMI ≥ 30) was 8% (41 women in controls and 43 in cases), none of the patients were diagnosed with malnutrition and smoking women with a low socioeconomic status only comprised 10% of the population (n = 102). Regardless, the benefits of a healthy diet (with an adequate consumption of fruits, vegetables and legumes) should be widespread in the population.

There were no problems recruiting participants. The response rate was very high, so selection bias was not unlikely. The food frequency questionnaire (FFQ) had been validated and used previously with Spanish women [44, 45]. Mothers of normal newborns were density matched to cases to avoid the influence of season on the responses for certain types of foods. Also, women were matched by age to decrease generational effects on their food habits: younger women show a trend to have a more westernized diet than older ones, who adhere more to the Mediterranean diet [46].

In case-control studies certain problems of anamnestic bias cannot completely be ruled out, as women are aware of the newborn condition and this could influence their answers. During prenatal care no advice is given on taking specific foods, apart from avoiding raw meat and fish and reducing consumption of big fish (presumably with a higher content of mercury and other heavy metals). We asked women about any change in diet during pregnancy: 48.8% of cases reported increased vegetable intake vs. 46.7% of controls; the figures for fruit were 59.9% vs. 58.3 and 23.2% and 22.2% for legumes in cases and controls respectively. The percentages of change are roughly similar (although slightly higher in cases) between cases and controls and thus we believe that in the case of misclassification bias, it is most likely to be non-differential.

Confounding bias can also not be completely dismissed. Differences in weight gain, smoking and other variables were controlled for in multivariate analysis. This is a limitation inherent to most observational studies. Known risk factors for SGA help to explain only 30–40% of all cases, indicating that there is still much to be known about the epidemiology of this condition. We have also tried to control this bias by collecting data on the well-known risk factors for SGA and adjusting for them in the multivariable models.

Regarding specific legumes, a significant negative association was found with kidney beans; with other legumes, protective ORs were observed in the highest categories of intake, although none of them reached significance. When total legume intake was assessed, a significant negative trend was observed: the higher the intake, the lower the SGA risk. We have failed to identify any other report in which the intake of legumes is related to SGA or low birthweight and thus we cannot compare our results to other work.

Conclusion

In conclusion, the intake of legumes and fruits seems to reduce the risk of SGA in Spanish women. Several vegetables containing selenium also reduced the incidence of SGA in our population. Nevertheless, the available information is scarce and more studies are needed on this subject.

Abbreviations

- AGA:

-

Adequate for gestational age

- aOR:

-

Adjusted odds ratio

- BMI:

-

Body mass index

- CIs:

-

Confidence intervals

- FFQ:

-

Food frequency questionnaire

- INMA:

-

“INfancia and Medio Ambiente” (INMA, INfancy and Environment)

- LGA:

-

Large for gestational age

- OR:

-

Odds ratio

- PH:

-

Poniente Hospital

- Q1:

-

Quintile 1

- Q2:

-

Quintile 2

- Q3:

-

Quintile 3

- Q4:

-

Quintile 4

- Q5:

-

Quintile 5

- ROLO:

-

Randomised cOntrol trial of LOw glycaemic index diet to prevent macrosomia

- SGA:

-

small for gestational age

- UGH:

-

University of Granada Hospital

- UH:

-

Ubeda Hospital

- UJH:

-

University of Jaen Hospital

References

American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. ACOG practice bulletin no. 134: fetal growth restriction. Obstet Gynecol. 2013;121:1122–33.

Kozuki N, Katz J, Christian P, Lee ACC, Liu L, Silveira MF, et al. Comparison of US birth weight references and the international fetal and newborn growth consortium for the 21st century standard. JAMA Pediatr. 2015;169(7):e151438.

Yi KH, Yi YY, Hwang IT. Behavioral and intelligence outcome in 8- to 16-year-old born small for gestational age. Korean J Pediatr. 2016;59(10):414–20.

Steiner N, Wainstock T, Sheiner E, Segal I, Landau D, Waslfisch A. Small for gestational age as an independent risk factor for long-term pediatric gastrointestinal morbidity of the offspring. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2017;4:1–5.

Chauhan SP, Rice MM, Grobman WA, Bailit J, Reddy UM, Wapner RJ, et al. MSCE, for the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NICHD) maternal-fetal medicine units (MFMU) network. Neonatal morbidity of small- and large-for-gestational-age neonates born at term in uncomplicated pregnancies. Obstet Gynecol. 2017;130(3):511–9.

Mendez-Figueroa H, Truong VT, Pedroza C, Khan AM, Chauhan SP. Small-for-gestational-age infants among uncomplicated pregnancies at term: a secondary analysis of 9 maternal-fetal medicine units network studies. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2016;215(5):628.e1–7.

Lee AC, Kozuki N, Cousens S, Setevens GA, Blencowe H, Silveira MF, et al. Estimates of burden and consequences of infants born small for gestational age in low and middle income countries with INTERGROWTH-21st standard: analysis of CHERG datasets. BMJ. 2017;358:j3677. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.j3677.

Black RE. Global prevalence of small for gestational age births. Nestle Nutr Inst Workshop Ser. 2015. https://doi.org/10.1159/000365790.

Gaudineau A. Prevalence, risk factors, maternal and fetal morbidity and mortality of intrauterine growth restriction and small-for-gestational age. J Gynecol Obstet Biol Reprod (Paris). 2013;42(8):895–910.

Chiavaroli V, Castorani V, Guidone P, Derraik JG, Liberati M, Chiarelli F, et al. Incidence of infants born small- and large-for-gestational-age in an Italian cohort over a 20-year period and associated risk factors. Ital J Pediatr. 2016;26(42):42.

Bushnik T, Yang S, Kaufman JS, Kramer MS, Wilkins R. Socioeconomic disparities in small-for-gestational-age birth and preterm birth. Health Rep. 2017;28(11):3–10.

Fisher SC, Van Zutphen AR, Romitti PA, Browne ML. National Birth Defects Prevention Study. Maternal hypertension, antihypertensive medication use, and small for gestational age births in the National Birth Defects Prevention Study, 1997–2011. Matern Child Health J. 2018;22(2):237–46.

Margerison Zilko CE, Rehkopf D, Abrams B. Association of maternal gestational weight gain with short- and long-term maternal and child health outcomes. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2010;202(6):574.e1–8.

Usynina AA, Grjibovski AM, Odland JØ, Krettek A. Social correlates of term small for gestational age babies in a Russian Arctic setting. Int J Circumpolar Health. 2016;75:32883. https://doi.org/10.3402/ijch.v75.32883 eCollection 2016.

McCowan L, Horgan RP. Risk factors for small for gestational age infants. Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol. 2009;23(6):779–93.

Parlapani E, Agakidis C, Karagiozoglou-Lampoudi T, Sarafidis K, Agakidou E, Athanasiadis A, et al. The Mediterranean diet adherence by pregnant women delivering prematurely: association with size at birth and complications of prematurity. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 13:1–8. https://doi.org/10.1080/14767058.2017.1399120.

Bain E, Crane M, Tieu J, Han S, Crowther CA, Middleton P. Diet and exercise interventions for preventing gestational diabetes mellitus. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015;4:CD010443. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD010443.pub2.

Ramón R, Ballester F, Iñiguez C, Rebagliato M, Murcia M, Esplugues A, et al. Vegetable but not fruit intake during pregnancy is associated with newborn anthropometric measures. J Nutr. 2009;139(3):561–7.

Mikkelsen TB, Osler M, Orozova-Bekkevold I, Knudsen VK, Olsen SF. Association between fruit and vegetable consumption and birth weight: a prospective study among 43,585 Danish women. Scand J Public Health. 2006;34(6):616–22.

Murphy MM, Stettler N, Smith KM, Reiss R. Associations of consumption of fruits and vegetables during pregnancy with infant birth weight or small for gestational age births: a systematic review of the literature. Int J Womens Health. 2014;6:899–912. https://doi.org/10.2147/IJWH.S67130 eCollection 2014.

Catov J, Bodnar LM, Ness RB, Markovic N, Roberts JM. Association of periconceptional multivitamin use and risk of preterm or small-for-gestational-age births. Am J Epidemiol. 2007;166(3):296–303.

Chen Y, Zhu B, Wu X, Li S, Tao F. Association between maternal vitamin D deficiency and small for gestational age: evidence from a meta-analysis of prospective cohort studies. BMJ Open. 2017;7(8):e016404. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2017-016404.

Ghaemi SZ, Forouhari S, Dabbaghmanesh MH, Sayadi M, Bakhshayeshkaram M, Vaziri F, et al. A prospective study of selenium concentration and risk of. Preeclampsia in pregnant Iranian women: a nested case-control study. Biol Trace Elem Res. 2013;152(2):174–9.

Mistry HD, Kurlak LO, Young SD, Briley AL, Pipkin FB, Baker PN, et al. Maternal selenium, copper and zinc concentrations in pregnancy associated with. Small-for-gestational-age infants. Matern Child Nutr. 2014;10(3):327–34.

Sun H, Chen W, Wang D, Jin Y, Chen X, Xu Y. The effects of prenatal exposure to low-level cadmium, lead and selenium on birth outcomes. Chemosphere. 2014;108:33–9.

Horan MK, McGowan CA, Gibney ER, Donnelly JM, FM MA. The association between maternal dietary micronutrient intake and neonatal. Anthropometry-secondary analysis from the ROLO study. Nutr J. 2015;14:105.

Zaragoza-Noguera R. Influence of the diet of the pregnant woman on fetal growth, Doctoral thesis. Murcia: University of Murcia; 2017.

Rayman MP. Selenium and human health. Lancet. 2012;379(9822):1256–68. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(11)61452-9.

Ricci E, Chiaffarino F, Cipriani S, et al. Diet in pregnancy and risk of small for gestational age birth: results from a retrospective case control study in Italy. Matern Child Nutr. 2010;6:297–305.

Delgado-Beltrán P, Melchor-Marcos JC, Rodríguez-Alarcón J, Linares-Uribe A, Fernández-Llebrez del Rey L, Barbazán-Cortés MJ, et al. The fetal development curves of newborn infants in the hospital de cruces (Vizcaya). I. Weight. An Esp Pediatr. 1996;44(1):50–4

Álvarez-Dardet C, Alonso J, Domingo A, Regidor E. La Medición de la Clase Social en Ciencias de la Salud, Informe de un Grupo de Trabajo de la Sociedad Española de Epidemiología. Madrid: SG Editores; 1995.

Townsend P, Davidson N. Inequalities in health, the Black report. Hammonsworth: Penguin; 1982.

Kessner DM, Singer J, Kalk CE. Infant death: an analysis by maternal risk and health care. Contrasts in health status. Washington: Institute of Medicine, National Academy of Sciences; 1973.

Fernández-Ballart JD, Piñol JL, Zazpe I, et al. Relative validity of a semi-. Quantitative food-frequency questionnaire in an elderly Mediterranean population of. Spain. Br J Nutr. 2010;103:1808.

Mataix VJ. Tabla de composición de alimentos españoles (Spanish food composition tables). Granada: Universidad de Granada; 2003.

Moreiras O, Carbajal A, Cabrera L, Cuadrado C. Tablas de composición de alimentos (Spanish food composition tables). Madrid: Pirámide; 2003.

Willett WC. Nutritional epidemiology. New York: Oxford University Press; 1998.

Institute of Medicine (US) Committee to Review Dietary Reference Intakes for Vitamin D and Calcium, Ross AC, Taylor CL, Yaktine AL, et al. Recommended dietary allowances and adequate intakes, elements. Washington: National Academies Press (US); 2011.

Mitchell EA, Robinson E, Clark PM, Becroft DM, Glavish N, Pattison NS, et al. Maternal birth size is not associated with maternal intake and status of folate during the second trimester nutritional risk factors for small for gestational age babies in a developed country: a case-control study. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed. 2004;89(5):F431–5.

Rao S, Yajnik CS, Kanade A, Fall CH, Margetts BM, Jackson AA, et al. Intake of micronutrient-rich foods in rural Indian mothers is associated with the size of their babies at birth: Pune maternal nutrition study. J Nutr. 2001;131(4):1217–24.

Salcedo-Bellido I, Martínez-Galiano JM, Olmedo-Requena R, Mozas-Moreno J, Bueno-Cavanillas A, Jimenez-Moleon JJ, et al. Association between vitamin intake during pregnancy and risk of small for gestional age. Nutrients. 2017;9(12):1277.

Martínez-González MA, Salas-Salvadó J, Estruch R, Corella D, Fitó M, Ros E, et al. Benefits of the Mediterranean diet: insights from the PREDIMED study. Prog Cardiovasc Dis. 2015;58(1):50–60.

Asociación EuroFIR AISBL. Spanish Database of Food Composition. http://www.bedca.net/ Accessed 26 Jan 2018.

De la Fuente-Arrillaga C, Ruiz ZV, Bes-Rastrollo M, Sampson L, Martinez-González MA. Reproducibility of an FFQ validated in Spain. Public Health Nutr. 2010;13(9):1364–72. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1368980009993065.

Olmedo-Requena R, Amezcua-Prieto C, de Dios L-D-CJ, Lewis-Mikhael AM, Mozas-Moreno J, Bueno-Cavanillas A, et al. Association between low dairy intake during pregnancy and risk of small-for-gestational-age infants. Matern Child Health J. 2016;20(6):1296–304.

Bibiloni MM, González M, Julibert A, Llompart I, Pons A, Tur JA. Ten-year trends (1999–2010) of adherence to the Mediterranean diet among the Balearic Islands’ adult population. Nutrients. 2017;9(7):749.

Acknowledgements

Women participating in the study and interviewers.

Funding

This work was supported by a grant from the National Institute of Health Carlos III [PI11/02199].

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request (Juan Miguel Martínez Galiano, email: juanmimartinezg@hotmail.com).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

MDR and JMMG conceived the study; MDR, JMMG, ABC, CAP, GGM and ISB designed the study; MDR, JMMG and ABC analysed the data. CAP, GGM, ISB and JMMG coordinated data collection. The first draft of the paper was written by MDR and JMMG. All the authors discussed, made contributions to the article and approved the final version.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Ethical approval was obtained from the Ethics Committees of the hospitals participating in the study: Comité de Ética de la Investigación del Complejo Hospitalario Universitario de Granada (Committee of Ethics of Investigation of the UGH), Comité de Ética de la Investigación del Hospital de Poniente (the Committee of Ethics of Investigation of the PH), Comité de Ética de la Investigación del Complejo Hospitalario Universitario de Jaén; (the Committee of Ethics of Investigation of the UJH) and Comité de Ética de la Investigación del Hospita de Úbeda (the Committee of Ethics of Investigation of the UB). The informed consent was verbally obtained because no interventions were performed on the study. It was to answer a survey’s questions. It was more pragmatic to obtain a verbal consent. The different Ethics Committes authorized and were aware about verbally consent use on the study. Informed consent was obtained from the women participating in the study and we followed the protocols established by the respective health centres for accessing data from medical records to carry out this type of research with the purpose of publication/disclosure to the scientific community.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Additional file

Additional file 1:

Questionnaire developed specifically for use in this study (DOC 721 kb)

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Martínez-Galiano, J., Amezcua-Prieto, C., Salcedo-Bellido, I. et al. Maternal dietary consumption of legumes, vegetables and fruit during pregnancy, does it protect against small for gestational age?. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 18, 486 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12884-018-2123-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12884-018-2123-4