Abstract

Background

A major change in the organisation of maternity care in the Netherlands is under consideration, going from an echelon system where midwives provide primary care in the community and refer to obstetricians for secondary and tertiary care, to a more integrated maternity care system involving midwives and obstetricians at all care levels. Student midwives are the future maternity care providers and they may be entering into a changing maternity care system, so inclusion of their views in the discussion is relevant. This study aimed to explore student midwives’ perceptions on the current organisation of maternity care and alternative maternity care models, including integrated care.

Methods

This qualitative study was based on the interpretivist/constructivist paradigm, using a grounded theory design. Interviews and focus groups with 18 female final year student midwives of the Midwifery Academy Amsterdam Groningen (AVAG) were held on the basis of a topic list, then later transcribed, coded and analysed.

Results

Students felt that inevitably there will be a change in the organisation of maternity care, and they were open to change. Participants indicated that good collaboration between professions, including a shared system of maternity notes and guidelines, and mutual trust and respect were important aspects of any alternative model. The students indicated that client-centered care and the safeguarding of the physiological, normalcy approach to pregnancy and birth should be maintained in any alternative model. Students expressed worries that the role of midwives in intrapartum care could become redundant, and thus they are motivated to take on new roles and competencies, so they can ensure their own role in intrapartum care.

Conclusions

Final year student midwives recognise that change in the organisation of maternity care is inevitable and have an open attitude towards changes if they include good collaboration, client-centred care and safeguards for normal physiological birth.

The graduating midwives are motivated to undertake an expanded intrapartum skill set. It can be important to involve students’ views in the discussion, because they are the future maternity care providers.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

The Dutch maternity care model has been held out as example of how to slow or reverse the march towards medicalisation of birth and technology driven specialist midwifery and maternity care [1–5]. However, unexpected high perinatal mortality reported at the turn of the 21st century raised concerns about the quality of the Dutch maternity care system resulting in a call for system change to enhance care [6–10]. Organisation, inter-professional relations and coordination have been identified as factors which may disrupt the smooth functioning of the maternity care. Issues such as a lack of a shared maternity notes system, misaligned financial incentives, different perspectives on antenatal health and suboptimal inter-professional communication have all been identified as contributing to systemic disorganisation [6]. Recent research indicated that clarity on each profession’s role and responsibilities within the collaboration seemed to be lacking and that many professionals did not perceive themselves as being an integral part of a team [7]. There has been a considerable rise in non-urgent referrals during labour from primary midwife-led care to obstetrician-led care [8, 9], challenging the sustainability of the current echelon system in the Netherlands with its strict role division between primary and secondary maternity care [6–10]. Therefore, major changes in the organisation of maternity care in the Netherlands are being considered, moving from an echelon system where midwives provide primary care in the community and refer to obstetricians for secondary and tertiary care, to a more integrated maternity care system involving midwives and obstetricians at all care levels [5, 11].

Current organisation of maternity care in the Netherlands

Like all health care, maternity care in the Netherlands is organised in echelons, with a strict role division between primary and secondary/tertiary care. The independent primary care midwife plays a key role as provider of standard maternity care in the Netherlands and provides one-to-one care to women during pregnancy, birth and the postpartum period in individual or group practices of midwives [12]. Primary care midwives have a gate keeping role: in the event of complications, an increased risk of complications, or a request for pharmacological pain relief, midwives transfer care of women to secondary care in a general hospital or to tertiary care in an academic referral centre, both with obstetricians and clinical midwives, who work under the responsibility of obstetricians. The Obstetrics Indications List [13] distinguishes between ‘physiological’ and ‘pathological’ pregnancies and births and directs all such referrals. There are tasks and responsibilities that currently fall outside the scope of primary care midwifery in the Netherlands, such as supervising medium risk pregnancies (obese or diabetic clients, clients with thyroid problems) and medium risk births (meconium-stained liquor, previous Caesarean section, pharmacological pain relief), and skills as monitoring the fetus with cardiotocography (CTG). Healthcare insurance companies reimburse secondary or tertiary care exclusively after referral for medical reasons [14]. In 2013, 85.4% of all pregnant women in the Netherlands started antenatal care with a primary care midwife, 50.6% started labour with a primary care midwife and 28.6% of all births (n = 167,159) were supervised by a primary care midwife at home or in a hospital or birth centre [15]. The Netherlands has more midwives (n = 2692) than specialists in obstetrics and gynaecology (n = 882) [16, 17].

Call for other forms of cooperation

Other countries took the rather unique Dutch maternity care system as an example for changing their maternity care systems [1, 9]. In these countries, such as New Zealand, Canada and the United Kingdom, midwives increasingly work autonomously and the homebirth rate is rising. Conversely, the quality of care of the ‘Dutch’ way of organising maternity care has been more and more questioned. Following reports of higher than anticipated perinatal mortality in the Netherlands [18], a government appointed Steering Committee [19] released its advisory report called ‘A good start’. Based on stakeholders’ opinions this committee presented a set of recommendations on the direction in which the Dutch maternity care should evolve in order to halve the perinatal mortality figures. The report contained the directive to improve the quality of maternity and perinatal care by encouraging closer cooperation and better communication between all maternity care professionals. Other recommendations by the Committee included local execution of multidisciplinary protocols developed on a national level and prevention of caregiver delay, specific attention for disadvantaged women, shared decision making and the accessibility of 24/7 maternity care.

Improved collaboration can be realised by implementing alternative maternity care models, such as integrated care in a joint venture with midwives and obstetricians (vertical integration), shared care within primary care (horizontal integration), or midwives working in the community as well as in the hospital [10, 20–22]. Health insurance companies supported this approach by strongly advising midwives and obstetricians to collaborate in a professional as well as a financial partnership [10]. Other forms of cooperation are feasible and a variety of maternity care models are being tested as pilots for a national model [7, 23]. There is, however, currently limited evidence to support any of the pilot approaches and no consensus among professionals and other stakeholders about whether, how and when the maternity care system should be integrated [7, 23–26]. Furthermore, the concept of integrated care is ambiguous and often used as an umbrella term [27]. Different stakeholders have given their opinions on the matter of integrated care [10, 11, 25, 26]. Although student midwives have been exposed to these different models in recent years, their voices have not been included in the conversation about change. Student midwives will be entering a changing maternity care system and it is important to involve students’ views in the discussion and the transitions, because they are the future maternity care providers with a unique perspective as semi-outsiders in the system who may have innovative perspectives as newly integrated members of the system. Further, it is important to gaining buy-in for any proposed change from future midwives. Final year students will have been part of various situations in their internships in different places in primary, secondary and tertiary care and were in that way in a position where they can observe what works and what does not work in the field. To our knowledge, no research has been conducted to investigate the views of midwifery students with regard to the reorganisation of maternity care.

Aim of the study

The purpose of this research was to explore the perceptions of graduating students regarding the organisation of maternity care and alternative maternity care models in the Netherlands. These student midwives have studied for 4 years, with 2 years in internships in primary, secondary and tertiary care and have witnessed new developments and have become part of the change. Findings from our study add the perspective of an important group of future professionals on how they see themselves fit in a changing system, which can further inform the direction of the current policy dialogue on the development of maternity care in the Netherlands. Our research question was: What are the perceptions of final year midwifery students in Amsterdam (VAA) and Groningen (VAG) on possible future forms of cooperation in maternity care, including integrated care?

Methods

Design

This qualitative descriptive study is based on an interpretivist/constructivist paradigm using a grounded theory design [28, 29]. This was an appropriate approach as our research question has a broad scope and there is relatively little prior knowledge about perspectives in the group under investigation. We conducted both individual interviews and focus group interviews with student midwives, letting these two methods complement each other [29]. Particularly delicate topics were more readily discussed in individual interviews covering maximum depth; whereas in a group interview, a more dynamic interaction between participants generated new ideas or evoked new insights that might not have been thought of in a one to one interview.

Recruitment and sample

Eligible participants were 79 final year student midwives of the Midwifery Academy Amsterdam Groningen (AVAG). From these female students, 45 studied in Amsterdam (VAA) and 34 in Groningen (VAG). Students were recruited from the AVAG on a web-based learning system used by schools for giving instructions to students and by approaching them face-to-face. To achieve variation in our sample, final recruitment was targeted at specific categories of student midwives, such as those who did not have an intention to work as active practising midwife, or had a child of their own. In total, 18 students participated; ten in individual interviews (seven in Amsterdam; three in Groningen) and eight (three and five respectively) students in two focus groups (Groningen). We intended to interview until we reached saturation of concepts.

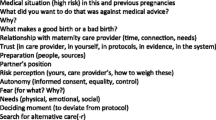

Data-collection

Information about the research project and interview procedure was provided on a web-based learning system and again face-to-face before the interview or focus group meeting. See our ethical/consent statement (Declaration B) for details on ethics approval and consent to participate. A topic guide (Table 1) was used to frame the questioning during the interviews to ensure key areas were discussed. If necessary, further exploratory questions were asked (for example, on the behavioural determinants: knowledge, norms, attitudes, and intention [30] and experiences). Six semi-structured interviews with midwifery students in Amsterdam (VAA) were conducted in the spring of 2014 by student midwives (MN and YC) after a 5-days training on interviewing and qualitative research and under supervision of the lead author, a psychologist and experienced interviewer (CW). Four interviews and two focus groups at the Midwifery Academy Groningen (VAG) were conducted by CW in the summer and autumn of 2014.

To increase validity of our findings, we used different source materials (data-triangulation), diverse researchers (investigator-triangulation) and a varied group of participants (negative case analysis). The participants were encouraged to speak freely about their experiences. The interviewers stressed their neutrality by exploring both positive and negative remarks of the participants. The interviews lasted 35 min on average (range: 18–56). At the conclusion of each interview the participants were invited to provide feedback on the interview and to verify a short oral summary. Directly after each interview the interviewers evaluated their findings and formulated areas that called for more in-depth exploration in the next interview. We kept a logbook (audit trail) in which we indicated with whom we had a conversation and about what or whether there were any special circumstances, where the conversation took place and what was going on in the media.

Participating students were individually invited by email to comment on the completed transcripts and preliminary results (member checking). All participants read, checked and approved these transcripts and results. Describing the results criteria [31] for reporting qualitative research (COREQ-criteria) were used. The final subthemes and main themes were discussed in a group session of health care professionals at conferences and with midwifery lecturers (peer debriefing).

Data analysis

Descriptive analyses were used to describe characteristics of the study population. The interviews were recorded on tape, transcribed and anonymised. The analyses of the qualitative data were done in a successive and cyclical order, using constant comparison/grounded theory design [28, 31]. The first six transcripts were analysed independently by all three interviewers, then reviewed to reach consensus on interpretation of the findings and to reflect on the research process and the role of the researchers. The transcripts were read several times to get a sense of the content of the whole. The material was first organised into information units and open coded (labelling), then axial coded (categorized) and finally selectively coded (thematically). More than one label or category could be added to a fragment of text. This analysis of the first six transcripts led to new ideas, which were used when again conducting new interviews with a number of students. These rounds of analyses were continued until we felt no new knowledge had or would present itself. We described the themes, compared the differences, recorded meaningful associations and compared the findings with existing literature. Examples of the analytical coding process are shown in Table 2. The analysis indicated data saturation, which means that the inclusion of further data would probably not have resulted in the identification of new themes.

Representative quotations were chosen to demonstrate the themes and subthemes identified; these are presented in the RESULTS section, each followed by the participant or focus group number. The quotes were translated into English by an accredited translator, and then translated back in Dutch by another investigator in order to check for validity of translation.

Results

In total, 18 students participated. The participants were between 21 and 28 years of age (mean = 23.4 years), one student was a mother. One student wanted to work as a researcher after graduation; the others all wanted to work as primary care midwives. All but one started the midwifery training in August 2010, one student started in August 2009.

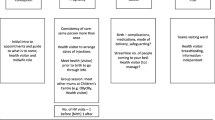

The data from the interviews identified four key issues in student midwives’ perception of the organisation of maternity care.

Schematic representation of the results

-

1)

Students are open to change

-

a)

Open attitude towards change

-

i)

Not stuck

-

ii)

flexible

-

i)

-

b)

Examples of maternity care models

-

i)

the current echelon system

-

ii)

other maternity care models

-

(1)

shared care within primary care (horizontal integration),

-

(2)

shared care between primary and secondary care (vertical integration),

-

(3)

midwives active in the community as well as in the hospital

-

(4)

CenteringPregnancy TM (group antenatal care).

-

(1)

-

i)

-

a)

-

2)

Students feel change is inevitable.

-

a)

Pressure from government and health Insurance companies

-

b)

Decline in numbers of home births,

-

c)

Social trend towards medicalisation

-

d)

Bad media coverage

-

i)

home birth

-

ii)

perinatal mortality figures

-

i)

-

e)

Resentment, lack of trust, power imbalance and ‘professional territorialism’ between occupational groups

-

i)

obstetricians vs. midwives

-

ii)

Primary care midwives vs. clinical midwives.

-

i)

-

a)

-

3)

Students accept change with conditions

-

a)

Provide the best possible care

-

b)

Essential components

-

i)

good collaboration, mutual trust and respect

-

ii)

client-centered care, empowerment

-

iii)

safeguard of normal birth, (pregnancy and childbirth is a fundamentally physiological process)

-

iv)

shared maternity notes system

-

v)

shared guidelines and protocols

-

vi)

emergency assistance accessible.

-

i)

-

a)

-

4)

Students need some reassurance about their role

-

a)

Profession could become redundant

-

b)

Interested in taking on new tasks and learning new skills

-

i)

supervising medium risk pregnancies

-

(1)

obese or diabetic clients, clients with thyroid problems, etc.

-

(1)

-

ii)

supervising medium risk births

-

(1)

births with meconium-stained liquor, previous Caesarean section, pharmacological pain relief, etc.

-

(1)

-

iii)

pick up new skills,

-

(1)

prescribing birth control, doing cardiotocography (CTG), vacuum extraction in primary care, etc.

-

(1)

-

i)

-

a)

Theme 1: Students are open to change

Although primarily trained as primary care midwives, the students had experienced examples of different approaches to care as part of their clinical educational trajectory with both the current echelon system as well as other, more integrated, maternity care models such as shared care within primary care (horizontal integration), shared care between primary and secondary care (vertical integration), midwives active in the community as well as in the hospital.

-

[I envision a] birth centre… a concentration of care, with the maternity care assistant, ultra sound centre, …a whole team of health care providers, not only obstetric care. [I had my internship..].. where the midwives were working in primary care as well as in the hospital. One day as primary care midwife, the next day as clinical midwife. The obstetricians in the hospital …as rear guard to do physiological (!) births. #6

In principle the students said they were open to change, possible because they were not yet established in their practice habits and had no financial obligations. The following quotes illustrate some of the student ideas about types of change and their openness to system change:

-

Well, I think that a new generation of midwifery students.. approach things in a fresher way and can also play a role in making this more usual but ...... in consultation and amicability, but sure, it will take a few years to overcome the old resentment, I think ” #2

-

So I think, yes, progress is always good of course… I just wonder whether it’s worth radically changing the whole system right now. #1

-

Obstetricians need midwives and midwives need obstetricians. So it should then basically … turn out OK. #5

Theme 2: Students feel change is inevitable

The students assumed that the way in which maternity care will be organised in the Netherland is about to change. Students identified reasons for the perceived inevitability of change including the pressure from government and health insurance companies, the overall decline in numbers of home births, a social trend towards medicalisation, the negative media coverage about home birth which the media erroneously related to the relatively high perinatal mortality figures, and the resentment, lack of trust, ‘professional territorialism’ and power imbalance between occupational groups (obstetricians versus midwives; primary care midwives versus clinical midwives). Highlights of the key aspects are evident in the following quotes:

-

…especially the insurers, in my view, want things to get better and otherwise they just don’t pay. I think that pressure is coming particularly from the insurers and from the state #2

-

…healthcare insurers are so incredibly powerful … pretty much omnipotent. #9

-

…because it has also been a bit of a trend in other countries, where you see that pregnancy and birth are much more medicalised. So I can imagine that the same is going to happen here, too. #1.

-

I think that people are also much less used to giving birth at home… # 5

-

Very often I have the feeling that the obstetrician thinks ‘you want to be autonomous, well you can just look after yourself then!’ And if you want to discuss something with this person, …they first want to see the client and once they’ve seen the client, they basically already take over the whole thing. #fg1

-

..you can clearly see that the secondary healthcare providers are trying to get a bit more power in the field of maternity care, and what you see is that midwives can quickly get pushed aside in the primary field #fg2

Theme 3: Students accept change with conditions

Students identified that an important condition to accepting any change in organisation of the maternity care system was, that they could (in their soon to be assumed role as primary care midwives) be able to provide the best possible care. Participants indicated that good collaboration between professions, including a shared maternity notes system and guidelines, and mutual trust and respect, were important aspects of any alternative model. Client-centred care, and the safeguard of the physiological, normalcy approach to pregnancy and birth should be maintained in any alternative model.

-

But sure, if it’s proven that the client could get better care from… that other system, integrated care, then I would … yes … change #3

-

I also think it’s a good thing if, for instance, obstetricians have consultancy hours in a midwife’s practice, meaning they get out of the hospital. And that midwives can indeed also go into hospitals to handle births with a slightly higher risk. #2

-

Perinatal mortality in the Netherlands … could also simply be reduced through better communication and better collaboration #8

-

…of essential importance ..is … midwifery wisdom … that you look holistically at the person herself #9

-

in other healthcare areas … integrated health care is indeed applied… but the big difference is … if you’re pregnant, then you’re not ill! You’re quite simply healthy and so why should you have to go into hospital? #3

Theme 4: Students need some reassurance about their role

Although the students said that they could support change under certain conditions, they feared that their primary care role in midwifery could become redundant or undermined and that the role of midwives could be marginalized. The students were afraid that, for instance, the midwives might only provide prenatal and postpartum care but no intrapartum care in the future.

As an anticipatory response to these concerns, students felt that there might be benefit in expanding their role and competence and to take on new tasks and responsibilities in primary care, some of which are common tasks for midwives in other countries but that currently fall outside the scope of primary care midwifery in the Netherlands. They gave examples such as: supervising medium risk pregnancies (obese or diabetic clients, clients with thyroid problems) and medium risk births (meconium-stained liquor, previous Caesarean section, pharmacological pain relief), and adding new skills, such as prescribing birth control, monitoring the fetus with cardiotocography (CTG) or doing vacuum extraction.

-

I think, how things will turn out, I think that in the end we’ll be allowed to do less. I think that ultimately the midwives will be permitted to do less and less and for instance that births… will be passed fully to what is now secondary healthcare and that we, for instance, will only do the prenatal checks. But that’s pretty much the worst scenario. But it’s possible. #1.

-

The more skills and actions you give up, then at a certain moment the less remains of your own professional profile. So maybe we should actually make sure we take on more tasks. #fg1

Discussion

This study aimed to explore student midwives’ perceptions on the current organisation of maternity care and alternative maternity care systems. Exploring the perspectives of students regarding the evolving role of midwives can help inform policy and enhance conversations about proposed system change. Our exploratory qualitative study adds to the evidence on barriers and facilitators to inter-professional collaboration in maternity care and provides a timely contribution to the literature as Dutch maternity care faces significant health system changes. Student midwife views contribute to a multifaceted understanding of how different echelons of care currently work together and how integrated care would impact women’s childbirth experiences.

Our descriptive thematic findings indicate that students perceived an inevitability regarding change in the organisation of maternity care, going from an echelon system with primary, secondary and tertiary care, to a more integrated maternity care system. Participants pointed out that good collaboration between professions, including a system of shared maternity notes and guidelines, and mutual trust and respect were important aspects of any alternative model. Students indicated that client-centred care, and the physiological, normalcy approach to pregnancy and birth should be safeguarded and maintained in any alternative model. Students worried that the role of midwives in intrapartum care may become minimised, and thus they are motivated to expand their scope of practice in order to enhance their role in providing intrapartum care.

We found that midwifery students had experienced a range of approaches identified in the literature as defining elements of models of maternity care including [32]: who provides the care (obstetricians, midwives, allied care providers), whether the providers are known to the woman, where the care occurs (at home, in hospital, community venue), when the care occurs (gestation at booking, frequency and length of visits, after hours contact), and how the care is provided (one-to-one or group visits) and as described as possible future maternity care models for Dutch practice [23]. Students identified shifts away from the original ‘echelon model’ and indicated openness to such change (theme 1). As in an explorative study among clinicians, working in community practices as well as in academic practices in maternity care in the USA in 2011 [33], when students in our study indicated a preference for a specific maternity care model, the motivation was mainly related to the desire to provide the best possible maternity care.

One of the reasons for the perceived inevitability of the change in organisation of maternity care (theme 2), according to the students, was the resentment, lack of trust and professional territorialism between midwives and obstetricians. Like our participating students, midwives have been found to report a power imbalance in which they feel to be viewed as inferior to obstetricians [9, 10]. A perceived power imbalance could harm inter-professional collaboration and may cause the experienced lack of trust [34]. The negative effect of the perceived power imbalance might be exacerbated by the obstetricians’ reported lack of knowledge about the midwives’ responsibilities and activities [10, 35]. Midwifery students in the Netherlands have some knowledge of the obstetrician’s and clinical midwives’ roles, yet medical students are rarely introduced to the roles of primary care midwives before they are required to work with them.

Our findings of essential components which are conditional for successful collaborative practice (theme 3) - such as the call for good collaboration between maternity care providers in mutual trust and respect; client-centered care and continuity of care; safeguarding of normal birth; a shared maternity notes system and shared guidelines - were also seen in other studies [9, 10]. Students are in a position where they can observe what works and what does not work in the field, because they were part of various situations in their internships in different places in primary, secondary and tertiary care.

Among Dutch maternity care professionals there is a lack of consensus regarding the distribution of responsibilities and tasks (theme 4) for moderate risk indications [7]. From 2000 to 2008, there was a considerable rise in non-urgent referrals from primary midwife-led care to obstetrician-led care during labour [6] and most referrals were for moderate risk indications [36]. Our study highlights that students see a need for expanding a primary care midwife’s responsibilities and competencies, similar to maternity care systems in other countries, such as the United Kingdom and Canada, where the midwife providing care to low risk woman commonly remains the caregiver when certain moderate risks occur [7, 24].

Lowering perinatal mortality was the main driver of changes in maternity care over the past decade in the Netherlands. The value of using such rare events as an indicator for assessing the quality of maternity care in developed countries is highly debatable [37, 38]. As a result of improved perinatal mortality statistics [39], the case for launching a radically altered perinatal care system does not seem evident anymore particularly with limited evidence and lack of peer-reviewed literature informing this radical shift in the Dutch maternity system. Nevertheless, rare and significant events such as perinatal mortality can provide an important starting point for in-depth studies aimed at understanding key issues relating to the care system. Our study contributes to that understanding.

Implementation of a new system can only be successful if there is support for change among all professionals and clients concerned [7, 40], and all stakeholders are ‘market ready’ [41] (Bruijnzeels; personal communication). There have been calls from different stakeholders to reconsider introducing integrated maternity care [40, 42]. Furthermore, it should not be forgotten that horizontal integration (cross-sectorial collaboration within primary care) is also key to counteracting the fragmentation of services in the health system [27, 43, 44]. Health care systems with a strong emphasis on primary care are more likely to provide better population health, greater economy in the use of resources and better distribution in health throughout the populations [45]. Birth models that are ideologically and practically based on the midwifery-led care (humanistic/holistic) model of maternity care produce better outcomes for mothers and babies than technocratic practices based on a more medical model of maternity care [2, 46–50], but they are also fragile and in need of more attention and valuation [51]. The functions of primary midwifery care, such as first contact, comprehensiveness and coordination, and the person and population health-focused view could give primary care a central role in coordinating and integrating care [2, 27]. Many countries saw responsibility move from midwives to obstetricians over the 20th century and in later years calls for more natural childbirth and more community based maternity services have contributed to a trend towards reintroducing or strengthening the roles of midwives [52]. Primary care midwives can be more aware of this added value they bring and advocate it more strongly in the collaboration with other care providers [40].

A limitation of our study might be that all but one of the interviewees were acquainted with the interviewers and that the researcher CW had a dual role as researcher and educator (but not examiner) with some interviewees. This ‘power-over’ relationship might have influenced the interviews; yet, it did not discourage the students from expressing positive as well as negative feelings and opinions and we do not believe the influence was negative or coercive in nature. The so-called investigator-triangulation (the collaboration of a qualitative reflexive interviewer (CW) with peer-interviewers (YC, MR)) brought together various ways of knowing (knowledge of the organisation of maternity care, the students midwives and academic researchers). The peer-interviewers improved the richness of qualitative data because they were able to establish deep rapport with participants, which enhances the process of sharing personal stories.

Another limitation might be that the focus group participants were familiar to each other. Their relationship may have caused participations to withhold certain experiences from their fellow students, and therefore from the focus group. On the other hand, it may have facilitated the discussion because they already knew each other. Our study did not include students from other midwifery academies.

The aim of our study was the empirical exploration of perceptions towards future maternity care models from the viewpoints of a sample of future midwives. However, trends for the future might mostly not be designed by the professionals-to-be who actually experience the changes in practices first hand, but imposed by legislative and governmental institutions or by highly placed iconic individuals [3, 5, 10]. Although we perceive the expectations of our target group to be valuable, one should thoughtfully interpret and use these expectations for future maternity care models. Expectations are not facts, and thus they might not come true. Nevertheless, it can be important to involve students’ views in the discussion, because student midwives are on the threshold of going to work as maternity care professionals. The findings of this qualitative study can provide the context for the planning and interpretation of a web-based survey among the whole population of final year student midwives in the Netherlands.

Conclusions

Our qualitative study on student midwives’ perceptions towards future maternity care models indicate that students are open to change and that shifts in the organization of maternity care would be facilitated by inter-professional collaboration. Students believed in the importance of client-centred care and the physiologic, normalcy approach to pregnancy and birth, regardless of model of care. Students were also motivated to expand their scope of practice in order to enhance their role in providing intrapartum care. It can be important to involve students’ views in the discussion, because they are the future midwives and are entering into a changing maternity care system. A survey among the whole population of final year student midwives in the Netherlands is recommended.

Notes

Parts of the manuscript has been presented as oral presentations at the European Forum of Primary Care (EFPC) in September 2015 in Amsterdam, the Netherlands, at the 16th Healthcare Interdisciplinary Research Conference (HIRC2015) in November 2015 in Dublin, Ireland, at the European Midwives Association Conference in November 2016 in London, UK and as a poster and oral presentation at Kennispoort, Utrecht, the Netherlands in January 2016.

Abbreviations

- AVAG:

-

Midwifery Academy Amsterdam and Groningen

- CPZ:

-

College Perinatal Care

- CTG:

-

CardioTocoGraphy

- EFPC:

-

European Forum of Primary Care

- HIRC:

-

Healthcare Interdisciplinary Research Conference

- KNOV:

-

Royal Dutch Organization of Midwives

- NIVEL:

-

Netherlands institute for health services research

- NVOG:

-

Dutch Society of Obstetrics and Gynaecology

- VAA:

-

Midwifery Academy Amsterdam

- VAG:

-

Midwifery Academy Groningen

References

Davis-Floyd RE, Barclay L, Tritten J, Daviss B-A. Introduction. In: Davis-Floyd RE, Barclay L, Daviss B-A, Tritten J, editors. Birth Models That Work. Berkely, Los Angeles, London: University of California Press; 2009.

de Jonge A, de Vries R, Lagro-Janssen AL, Malata A, Declercq E, Downe S, Hutton EK. The importance of evaluating primary midwifery care for improving the health of women and infants. Front Med (Lausanne). 2015;2:17. doi:10.3389/fmed.2015.00017.

de Vries R. A Pleasing Birth: midwives and maternity care in the Netherlands. Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press; 2005.

de Vries R, Wiegers TA, Smulders B, van Teijlingen E. The Dutch obstetrical system; vanguard of the future in maternity care. In: Davis-Floyd RE, Barclay L, Daviss B-A, Tritten J, editors. Birth Models That Work. Berkely, Los Angeles, London: University of California Press; 2009.

De Vries R, Nieuwenhuijze M, Buitendijk SE, members of Midwifery Science Work Group. What does it take to have a strong and independent profession of midwifery? Lessons from the Netherlands. Midwifery. 2013;29(10):1122–8.

Schölmerich VL, Posthumus AG, Ghorashi H, Waelput AJ, Groenewegen P, Denktaş S. Improving interprofessional coordination in Dutch midwifery and obstetrics: a qualitative study. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2014;14:145. doi:10.1186/1471-2393-14-145.

van der Lee N. Tailoring CanMEDS for training in Obstetrics and Gynaeacology in the Netherlands. 2014. Thesis: VU Amsterdam.

Offerhaus PM, Hukkelhoven CW, de Jonge A, van der Pal-de Bruin KM, Scheepers PL, Lagro-Janssen AL. Persisting rise in referrals during labor in primary midwife-led care in the Netherlands. Birth. 2013;40(3):192–201. doi:10.1111/birt.12055.

Perdok H, De Jonge A, Manniën J, Mol BW. Opinions of maternity care professionals about integration of care during labour for ‘moderate risk’ indications: a Delphi study in the Netherlands. Birth. 2014;41(2):195–205. doi:10.1111/birt.12102.

Posthumus AG, Schölmerich VL, Waelput AJ, Vos AA, De Jong-Potjer LC, Bakker R, Bonsel GJ, Groenewegen P, Steegers EA, Denktaş S. Bridging between professionals in perinatal care: towards shared care in the Netherlands. Matern Child Health J. 2013;17(10):1981–9. doi:10.1007/s10995-012-1207-4.

de Vries, R. Verloskunde staat voor een historisch keerpunt [Midwifery care at historical turning point]. Volkskrant 27 maart 2014.

KNOV. Beroepsprofiel. [Profile of the profession]. 2014. URL http://www.knov.nl/scholing-en-registratie/tekstpagina/31/beroepsprofiel/. Accessed 10 Sept 2015.

College voor zorgverzekeringen. Verloskundig Vademecum [Obstetric Manual]. Diemen: College voor zorgverzekeringen; 2003.

Bais JMJ, Pel M. The basis of the Dutch obstetric system: risk selection. Eur Clin Obstet Gynaecol. 2007;2(4):209–12.

The Netherlands Perinatal Registry. Perinatal Care in the Netherlands 2013. Utrecht: The Netherlands Perinatal Registry; 2014.

Hingstman L, van Hassel DTP, Kenens RJ. Cijfers uit de registratie van verloskundigen: peiling 2012. [Data from the registration of midwives 2012]. Utrecht: NIVEL; 2013.

van Greuningen M, Batenburg R, Hansen J. De arbeidsmarkt voor gynaecologen in Nederland Stand van zaken in 2009, met een behoefteraming voor 2027 [The labor market for obstetricians in the Netherlands. Situation in 2009 and an estimation for 2027]. Utrecht: NIVEL; 2009.

Peristat II. EURO-PERISTAT. Project with SCPE and EUROCAT. European Perinatal Health Report. Data 2004. 2008. Available http://www.europeristat.com/reports/european-perinatal-health-report2004.html

Stuurgroep Zwangerschap en geboorte. Een goed begin, veilige zorg rond zwangerschap en geboorte [A good start, safe care for pregnancy and birth. Advice of the Committee on Good care during pregnancy and child birth]. Utrecht: Advies Stuurgroep Zwangerschap en Geboorte; 2009.

CPZ. [Samenwerking in de geboortezorg: positieve ontwikkelingen, knelpunten en oplossingen; brief aan minister Schippers, 18 maart 2014 [Collaboration in maternity care: positive developments, bottlenecks and solutions –letter to Minister Schippers, 18 March 2014]. URL https://www.rijksoverheid.nl/documenten/brieven/2014/03/18/brief-over-samenwerking-in-de-geboortezorg. Accessed 10 Sept 2015.

de Groot CJM. Als de zwangere ziek wordt - Oratie [When the pregnant woman gets ill]. 2011. http://www.alsdezwangereziekwordt.nl. Accessed 10 Sept 2015.

Schippers EI. Kamerbrief over voortgang zwangerschap en geboorte [Letter to Parliament about progress on pregnancy and birth]. 2014. https://www.rijksoverheid.nl/documenten/kamerstukken/2014/06/02/kamerbrief-over-voortgang-zwangerschap-en-geboorte. Accessed 10 Sept 2015.

CPZ (College Perinatale Zorg). De geboortezorgorganisatie: Organisatiemodellen integrale geboortezorg - concept. [The organisation of maternity care: models of organisation of integral maternity care – draft]. 2015.

Jans S, Perdok H, Mol BW, De Jonge A. Integratie van zorg tijdens de baring: de INCAS studie. [Integration of care during labour and birth: the INCAS study]. Tijdschrift voor Verloskundigen. 2014;1:47–51.

KNOV Position paper, March 2014. URL http://www.knov.nl/actueel-overzicht/nieuws-overzicht/detail/position-paper-knov-over-integrale-zorg/1351. Accessed 10 Sept 2015.

NVOG. Visiedocument ‘Integrale verloskundige zorg; Een stap verder’ [Vision Document: integral maternity care; one step further]. 2014. URL., http://www.nvog.nl/voorlichting/Nieuws-+en+persberichten/Integrale+verloskundige+zorg+Een+stap+verder.aspx. Accessed 3 July 2015.

Valentijn PP, Schepman SM, Opheij W, Bruijnzeels MA. Understanding integrated care: a comprehensive conceptual framework based on the integrative functions of primary care. Int J Integr Care. 2013;13:e010.

Baarda B. Research. This is it! Guidelines how to design, perform and evaluate quantitative and qualitative research. 2nd ed. Groningen/Houten: Noordhoff Uitgevers; 2014.

Boeije H. Analyseren in kwalitatief onderzoek [Analysis in qualitative research]. Den Haag: Boom Lemma Uitgevers; 2008.

Brug J, van Assema P, Lechner L. Gezondheidsvoorlichting en gedragsverandering [Health education and behaviour change]. Assen: Van Gorcum; 2012.

Tong A, Sainsbury P, Craig J. Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ). Int J Qual Health Care. 2007;19(6):349–57.

Allen J, Gibbons K, Beckmann M, Tracy M, Stapleton H, Kildea S. Does model of maternity care make a difference to birth outcomes for young women? A retrospective cohort study. Int J Nurs Stud. 2015;52(8):1332–42. doi:10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2015.04.011. Epub 2015 Apr 23.

Avery MD, Montgomery O, Brandl-Salutz E. Essential components of successful collaborative maternity care models: the ACOG-ACNM project. Obstet Gynaecol Clin North Am. 2012;39(3):423–34. doi:10.1016/j.ogc.2012.05.010.

D’Amour D, Ferrada-Videla M, San Martin Rodriguez L, Beaulieu MD. The conceptual basis for interprofessional collaboration: core concepts and theoretical frameworks. J Interprof Care. 2005;19 Suppl 1:116–31.

King TL, Laros Jr RK, Parer JT. Interprofessional collaborative practice in obstetrics and midwifery. Obstet Gynaecol Clin North Am. 2012;39(3):411–22. doi:10.1016/j.ogc.2012.05.009. Epub 2012 Aug 11.

Perdok H, Jans S, Verhoeven C, van Dillen J, Mol BW, de Jonge A. Intrapartum referral from primary to secondary care in the Netherlands: a retrospective cohort study on management of labor and outcomes. Birth. 2015;42(2):156–64. doi:10.1111/birt.12160. Epub 2015 Apr 6.

Escuriet R, White J, Beeckman K, Frith L, Leon-Larios F, Loytved C, Luyben A, Sinclair M, van Teijlingen E, EU COST Action IS0907. ‘Childbirth Cultures, Concerns, and Consequences’. Assessing the performance of maternity care in Europe: a critical exploration of tools and indicators. BMC Health Serv Res. 2015;15:491. doi:10.1186/s12913-015-1151-2.

Garssen J, Van der Meulen A. Ontwikkelingen rond de perinatale sterfte in Nederland. [Developments around the perinatal mortality in the Netherlands] Bevolkingstrends. 2004;52(3):15–31. Voorburg/Heerlen: CBS.

Peristat III. EURO-PERISTAT. Project with SCPE and EUROCAT. European Perinatal Health Report. The health and care of pregnant women and babies in Europe in 2010. 2013. Available http://www.europeristat.com/reports/european-perinatal-health-report-2010.html.

Wichmann C. Oproep tot herbezinning invoering integrale geboortezorg [Call for reconsideration introduction integral maternity care] URL http://www.clara-wichmann.nl/nieuws/2016/oproep-tot-herbezinning-invoering-integrale-geboortezorg. Accessed 4 Mar 2016.

Henneman EA. Nurse-physician collaboration: a poststructuralist view. J Adv Nurs. 1995;22(2):359–63.

Hallensleben E. Knelpunten bij de Integrale zorg [Bottlenecks in integrated care]. http://www.evaa.nl/docs/20160223161522_EricHalKnelpunten_bij_de_Integrale_Zorg_def_(1)-1.pdf. Gouda: 13/2/2016. Accessed 8 Apr 2016.

Valentijn PP, Vrijhoef HJ, Ruwaard D, de Bont A, Arends RY, Bruijnzeels MA. Exploring the success of an integrated primary care partnership: a longitudinal study of collaboration processes. BMC Health Serv Res. 2015;15:32. doi:10.1186/s12913-014-0634-x.

Valentijn PP, Vrijhoef HJ, Ruwaard D, Boesveld I, Arends RY, Bruijnzeels MA. Towards an international taxonomy of integrated primary care: a Delphi consensus approach. BMC Fam Pract. 2015;16:64. 10.1186/s12875-015-0278-x.

Starfield B. Primary care: an increasingly important contributor to effectiveness, equity, and efficiency of health services. SESPAS report2012. GacSanit. 2012;26(Suppl1):20–6. doi:10.1016/j.gaceta.2011.10.009.

Hatem M, Sandall J, Devane D, Soltani H, Gates S. Midwife-led versus other models of care for childbearing women. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2008;4:CD004667. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD004667.pub2.

Prins M, van Dillen J, de Jonge A. Voordelen van continue zorg door verloskundigen. [The advantages of continuity of care given by midwives]. Ned Tijdschr Geneeskd. 2014;158:A7070.

Renfrew MJ, McFadden A, Bastos MH, Campbell J, Channon AA, Cheung NF, Silva DR, Downe S, Kennedy HP, Malata A, McCormick F, Wick L, Declercq E. Midwifery and quality care: findings from a new evidence-informed framework for maternal and newborn care. Lancet. 2014;384(9948):1129–45. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(14)60789-3. Epub 2014 Jun 22.

Sandall J, Soltani H, Gates S, Shennan A, Devane D. Midwife-led continuity versus other models of care for childbearing women. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013;(8):CD004667. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD004667.pub3.

Wiegerinck MM, van der Goes BY, Ravelli AC, van der Post JA, Klinkert J, Brandenbarg J, Buist FC, Wouters MG, Tamminga P, de Jonge A, Mol BW. Intrapartum and neonatal mortality in primary midwife-led and secondary gynaeacologist-led care in the Amsterdam region of the Netherlands: A retrospective cohort study. Midwifery. 2015. doi: 10.1016/j.midw.2015.08.007.

Davis-Floyd RE, Barclay L, Daviss B-A, Tritten J. Conclusion. In: Davis-Floyd RE, Barclay L, Daviss B-A, Tritten J, editors. Birth Models That Work. Berkely, Los Angeles, London: University of California Press; 2009.

Rowland T, McLeod D, Froese-Burns N. Comparative study of maternity systems. 2012. URL http://www.health.govt.nz/publication/comparative-study-maternity-systems. Accessed 4 Mar 2016.

Acknowledgments

The authors are indebted to the midwifery students and the Midwifery Academy Amsterdam Groningen. Furthermore, we would like to thank Lianne Holten for her contribution to earlier versions of this article.

Funding

This study was funded by the Academy of Midwifery Amsterdam-Groningen.

Availability of data and materials

We are not willing to share the qualitative data sets (the interview transcripts) in the main paper or additional supporting files in order to protect respondent confidentiality. Although we did remove personal identifiers in the interview transcripts (such as the name and mail-address), the transcripts will likely contain references to the contextual identifiers in individual students’ stories and make individual students (in our small school population) identifiable. On request and under certain conditions, we can provide access to the transcripts and audit trail. Please keep in mind, that the documents are written in Dutch.

Authors’ contribution

CW originated and supervised the study. YC, MR and CW recruited the participants. YC and MR both interviewed three students, CW interviewed twelve students (four individual interviews and two focus groups). All authors drafted the manuscript and approved the final manuscript.

Authors’ information

1. J. Catja Warmelink (catja.warmelink@inholland.nl) is Ph.D. student at the department of Midwifery Science, AVAG and the EMGO Institute for Health and Care Research, VU University Medical Center, Amsterdam, The Netherlands and senior lecturer at the Midwifery Academy Amsterdam-Groningen in Groningen, The Netherlands. She earned her university Master’s degree in development psychology at the university of Groningen. Her current research interests include organisation of midwifery care and perinatal psychology.

2. T. Paul De Cock ( p.decock@ulster.ac.uk) was senior researcher at the department of Midwifery Science, AVAG and the EMGO Institute for Health and Care Research, VU University Medical Center, Amsterdam, The Netherlands and manager and lecturer in psychology at the Midwifery Academy Amsterdam-Groningen in Groningen, the Netherlands. Currently he is working as research associate at The Bamford Centre for Mental Health and Wellbeing, University of Ulster, Northern Ireland. He earned his Ph.D. in Psychology at the University of Ulster, Northern Ireland. His current research interests are in perinatal psychology and development.

3. Yvonne Combee (yvonne_combee@msn.com) graduated in 2014 at the Midwifery Academy Amsterdam-Groningen in Amsterdam, The Netherlands. She is working as a registered primary care midwife now in Doetinchem, the Netherlands.

4. Marloes Rongen (marloesrongen@live.nl) graduated in 2014 at the Midwifery Academy Amsterdam-Groningen in Amsterdam, The Netherlands. She is working as a registered primary care midwife now in Leiden, the Netherlands.

5. Therese A. Wiegers (t.wiegers@nivel.nl) is psychologist, epidemiologist and senior researcher at Netherlands institute for health services research (NIVEL) in Utrecht, the Netherlands. She earned her Ph.D. at the Leiden University, the Netherlands. Her current research interest include midwifery care, maternity care and reproductive health.

6. Eileen K. Hutton (huttone@mcmaster.ca) was Professor Midwifery Science, AVAG and the EMGO Institute for Health and Care Research, VU University Medical Center, Amsterdam, and is Assistant Dean Faculty of Health Sciences, Director Midwifery Education Program and Associate Professor Obstetrics and Gynecology of the McMaster University in Hamilton, Canada and she is a Registered midwife. She earned his Ph.D. in clinical epidemiology at the university of Toronto, Canada. Her current research interest include the quality and organisation of midwifery care.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have are no competing interests.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study was carried out in conjunction with the national DELIVER study, which obtained ethical approval by the Medical Ethics Committee of the VU University Medical Centre in Amsterdam, the Netherlands (WC 008-100). All participants from the individual interviews and focus groups received written and verbal information about the aim and content of the interviews, and they each gave written informed consent to be interviewed and audio taped. The researchers assured confidential handling of the interview data and signed the confidentiality agreement on each participant’s consent form. The interviewees were free to participate and could withdraw from the study at any time without giving any reasons. To increase the validity of our findings, the final subthemes and main themes were discussed in group sessions of health care professionals at conferencesFootnote 1, and with midwifery lecturers and students.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Warmelink, J.C., de Cock, T.P., Combee, Y. et al. Student midwives’ perceptions on the organisation of maternity care and alternative maternity care models in the Netherlands - a qualitative study. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 17, 24 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12884-016-1185-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12884-016-1185-4