Abstract

Background

Streptococcus uberis, the most frequent cause of mastitis in lactating cows, is considered non-pathogenic for humans. Only a few case reports have described human infections with this microorganism, which is notoriously difficult to identify.

Case presentation

We report the case of a 75-year-old male haemodialysis patient, who developed a severe foot infection with osteomyelitis and bacteraemia. Both Streptococcus uberis and Staphylococcus aureus were identified in wound secretion and blood samples using mass spectrometry. The presence of Streptococcus uberis was confirmed by superoxide dismutase A sequencing. The patient recovered after amputation of the forefoot and antibiotic treatment with ampicillin/sulbactam. He had probably acquired the infection while walking barefoot on cattle pasture land.

Conclusion

This is the first case report of a human infection with Streptococcus uberis with identification of the microorganism using modern molecular technology. We propose that Staphylococcus aureus co-infection was a prerequisite for deep wound and bloodstream infection with Streptococcus uberis.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

End-stage renal disease is a state of severe immunodeficiency and dialysis patients are prone to infectious complications. We describe a haemodialysis patient who acquired a wound infection and bacteraemia with Streptococcus uberis, which is a microorganism that causes mastitis in cows but is considered non-pathogenic in humans. We propose that invasive infection was facilitated by a co-infection with Staphylococcus aureus. In addition, we provide an overview of case reports of S. uberis infections in humans.

Case presentation

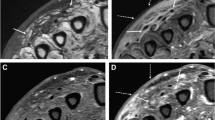

A 75-year-old male Caucasian haemodialysis patient presented with painful swelling and redness of his right forefoot. He had a fever of 39.0 °C and hypotension. C-reactive protein was elevated at 300 mg/l and interleukin-6 was 1120 pg/ml. His leukocyte count was 20 G/l. One week earlier he had fallen and suffered subluxation of the second and third metatarsophalangeal joints of the right foot. Two days later a haemorrhagic plantar bulla developed. At presentation a secreting ulcer was visible at the region of the second and third metatarsophalangeal joints. In a swab specimen taken from wound secretion methicillin-susceptible S. aureus, Acinetobacter baumannii, Proteus vulgaris, S. uberis and Clostridium perfringens were cultured. A concomitant blood culture sample was positive for S. aureus and S. uberis.

The first toe had been amputated 4 months earlier because of staphylococcal osteomyelitis. The previous year he had had an abscess on the left forefoot with septicaemia caused by methicillin-resistant staphylococci, and this had required surgical drainage.

Clinically significant peripheral arterial vascular disease was excluded. The next day an urgent transmetatarsal amputation of the right forefoot was performed. A deep wound swab led to growth of S. aureus and S. uberis. Histology showed a fistulating ulcer affecting the bones, putrid thrombophlebitis and gangrene of the plantar soft tissue. The patient was treated with intravenous ampicillin 2 g/sulbactam 1 g after each haemodialysis for the following 3 weeks. His clinical condition and inflammatory parameters rapidly improved. Wound healing was protracted and a secondary infection with S. aureus was treated with linezolid. Six weeks after the incident the patient had completely recovered.

The isolate of S. uberis was initially identified using matrix-assisted laser desorption ionisation time-of-flight mass spectrometry (MALDI TOF) (MALDI Biotyper©Microflex LT, Bruker Daltonics, Bremen, Germany). The S. uberis isolate obtained from the blood culture was sent to the German National Reference Centre for Streptococci, where the correct classification was confirmed by sequencing the superoxide dismutase A gene.

Discussion

To the best of our knowledge this is the first description of S. uberis infection in a haemodialysis patient. S. uberis is the most common pathogen causing mastitis in cows worldwide [1]. S. uberis causes painful inflammation of the udder and decreases the quantity and quality of milk production. Because of antibiotic treatment of cows, S. uberis isolates with decreased susceptibility to penicillin, macrolides, aminoglycosides and clindamycin are increasingly reported [2]. S. uberis infection of cattle usually occurs after environmental exposure. One study showed S. uberis in 63 % of environmental samples such as water, soil, plant matter and hay [3]. In addition, 23 % of 104 fecal samples were positive for S. uberis, with the highest proportion observed during the summer grazing season. Therefore, fecal shedding is probably the main source of S. uberis infections in cattle.

S. uberis is considered non-pathogenic to humans. The species difference in pathogenicity is at least partly explained by the fact that S. uberis plasminogen activator (SUPA) activates bovine, but not human, plasminogen [4]. Activation of the plasminogen system causes degradation of the extracellular matrix and facilitates spreading of bacteria and invasive infection.

S. uberis belongs to the family of viridans streptococci. This pathogen has rarely been identified in human clinical microbiological samples. S. uberis has been reported as a cause of urinary tract infection. Gülen et al. described seven cases out of 148 culture-positive urinary tract infections from patients living in a rural Turkish region [5]. The authors speculate that patients became infected through frequent contact with cows and milk. One other case of S. uberis urinary tract infection was described by Lazinska et al. in 47 urine samples from 42 renal transplant recipients [6]. Unfortunately, clinical presentation, treatment and outcome in patients with S. uberis urinary tract infection have not been specified in detail. S. uberis has also been found to be a cause of bacterial pneumonia. Sarkar et al. described three cases of pneumonia with positive blood cultures [7]. All three patients recovered with iv penicillin therapy. Murdoch and MacFarlane described S. uberis as the cause of abscess formation after a scalp laceration from a horse kick in a child [8]. The child recovered after drainage and antibiotic therapy with amoxicillin and cotrimoxazole. Another case report described gonarthritis and soft tissue abscess caused by S. uberis [9]. The patient was treated with surgical drainage and cefuroxime, clindamycin and penicillin. In addition, endocarditis in a child with Down syndrome and an atrioventricular canal has also been reported [10]. A case of postoperative S. uberis endophthalmitis after phacoemulsification and vitrectomy for proliferative diabetic nephropathy has been described in a patient with diabetes and end-stage renal disease on peritoneal dialysis [11]. Sanches et al. reported a rancher, in whom S. uberis was identified from a hepatic abscess [12]. Table 1 shows previous reports of S. uberis infection. In summary, including our case we were able to identify 17 cases of S. uberis infection. In eight of these cases direct or indirect contact with cattle or milk and dairy products was suspected.

Our case is exceptional in several respects. First, to the best of our knowledge this is the only case in which the presence of S. uberis in a human clinical sample was confirmed by modern methodology, including MALDI TOF and superoxide dismutase A gene sequencing. These tests are currently the best methods for unequivocal classification of S. uberis [13, 14]. S. uberis is notoriously difficult to identify. In a study of 1227 S. viridans clinical human samples seven were initially classified as S. uberis [15]. However, in retrospect, using newer technology all of these samples were reclassified as Globicatella sanguinis [16]. In addition, S. uberis and enterococci appear to be difficult to distinguish by phenotypical testing only [17]. In the case reports listed in Table 1 diagnosis of S. uberis was established by phenotypical testing. Some of these infections might have been misclassified as previously suspected [18].

Second, this is the only report of S. uberis and S aureus co-infection requiring an amputation. Thirdly, to the best of our knowledge concomitant S. uberis wound infection and bacteraemia have also not been previously reported. In addition, our patient had deep wound infection with osteomyelitis and bacteraemia caused by S. uberis and S. aureus coinfection. He also had a mixed wound infection including several other bacteria that were found in superficial wound secretion. From a clinical point of view the exact pathogenetic roles of S. uberis and S. aureus are difficult to determine in our case. Because S. aureus is a highly pathogenic and tissue-invasive bacteria, we speculate that it was the primary and leading pathogen and facilitated subsequent invasion by S. uberis. Whether S. uberis alone would have been able to cause the severe infection is unknown but we believe this is unlikely. Notably, none of the other case reports mentioned co-infection with other more aggressive bacteria. Fortunately, S. uberis and S. aureus that were present in the deep wound and blood were susceptible to all tested antibiotics and the patient quickly recovered under ampicillin/sulbactam treatment. In case of a difference in antibiotic susceptibility between them we would have chosen an antibiotic combination therapy to target both organisms.

Notably, our case of a haemodialysis patient with wound infection and bacteraemia, a case of a peritoneal dialysis patient with endophthalmitis and a case of a renal transplant patient with urinary tract infection suggest that patients on renal replacement therapy are particularly susceptible to S. uberis infection [6, 11].

The last remaining question is how the patient acquired this rare infection. He had suffered two additional serious foot infections in the preceding year. The patient was a staunch barefoot walker and had calloused feet with multiple lacerated wounds on his soles. During the summer months he used to hike barefoot across mountain pastures. Summer is also the cattle grazing season, when alpine pastures are densely populated by cows. We believe that the patient inadvertently stepped in one of the innumerable cow pats that cover alpine pastures, thereby translocating the cow's faecal shedding into the cutaneous clefts. His fall with subluxation of the toe may have caused some of this material to translocate into deeper tissues, where it served as a nidus for the infection.

Conclusion

In summary, we report the first case of S. uberis osteomyelitis and wound and bloodstream infection in a haemodialysis patient. This is the only case of a human infection that was diagnosed by modern microbiological methodology. Invasive infection was most likely facilitated by S. aureus co-infection. We recommend that immunocompromised patients should not to walk barefoot over cattle grazing pastures.

Consent

Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for publication of this Case report. A copy of the written consent is available for review by the Editor of this journal.

References

Leigh JA. Streptococcus uberis: a permanent barrier to the control of bovine mastitis? Vet J. 1999;157(3):225–38.

Overesch G, Stephan R, Perreten V. Antimicrobial susceptibility of gram-positive udder pathogens from bovine mastitis milk in Switzerland. Schweiz Arch Tierheilkd. 2013;155(6):339–50.

Zadoks RN, Tikofsky LL, Boor KJ. Ribotyping of Streptococcus uberis from a dairy's environment, bovine feces and milk. Vet Microbiol. 2005;109(3–4):257–65.

Zhang Y, Gladysheva IP, Houng AK, Reed GL. Streptococcus uberis plasminogen activator (SUPA) activates human plasminogen through novel species-specific and fibrin-targeted mechanisms. J Biol Chem. 2012;287(23):19171–6.

Gülen DKA, Aydin M, Tanriverdi Y. Urinary tract infections caused by streptococcus uberis: apathogen of bovine mastitis-report of seven cases. Afr J Microbiol Res. 2013;7(30):3908–12.

Lazinska B, Ciszek M, Rokosz A, Sawicka-Grzelak A, Paczek L, Luczak M. Bacteriological urinalysis in patients after renal transplantation. Pol J Microbiol. 2005;54(4):317–21.

Sarkar TK, Murarka RS, Gilardi GL. Primary Streptococcus viridans pneumonia. Chest. 1989;96(4):831–4.

Murdoch DRSL, MacFarlane MR. Human wound infection with streptococcus uberis. Clinical Microbiology Newsletter. 1997;19(22):174. 175.

Kessel S, Wittenberg CE. Joint infection in a young patient caused by Streptococcus uberis, a pathogen of bovine mastitis—a case report. Z Orthop Unfall. 2008;146(4):507–9.

Bouskraoui M, Benbachir M, Abid A. Streptococcus uberis endocarditis in an infant with atrioventricular defect. Arch Pediatr. 1999;6(4):481.

Velez-Montoya R, Rascon-Vargas D, Mieler WF, Fromow-Guerra J, Morales-Canton V. Intravitreal ampicillin sodium for antibiotic-resistant endophthalmitis: streptococcus uberis first human intraocular infection report. J Ophthalmol. 2010. doi:10.1155/2010/169739.

Sanchez J, Moreno JJ, Roldan A, Ildefonso JA, Florensa J. Hepatic abscess caused by Streptococcus uberis. Enferm Infecc Microbiol Clin. 1991;9(3):189–90.

Raemy A, Meylan M, Casati S, Gaia V, Berchtold B, Boss R, et al. Phenotypic and genotypic identification of streptococci and related bacteria isolated from bovine intramammary infections. Acta Vet Scand. 2013;55:53.

Alber J, El-Sayed A, Lammler C, Hassan AA, Zschock M. Polymerase chain reaction mediated identification of Streptococcus uberis and Streptococcus parauberis using species-specific sequences of the genes encoding superoxide dismutase A and chaperonin 60*. J Vet Med B Infect Dis Vet Public Health. 2004;51(4):180–4.

Facklam RR. Physiological differentiation of viridans streptococci. J Clin Microbiol. 1977;5(2):184–201.

Facklam R. What happened to the streptococci: overview of taxonomic and nomenclature changes. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2002;15(4):613–30.

Fortin M, Messier S, Pare J, Higgins R. Identification of catalase-negative, non-beta-hemolytic, gram-positive cocci isolated from milk samples. J Clin Microbiol. 2003;41(1):106–9.

Toma L, Di Domenico EG, Prignano G, Ensoli F. Comment on “Intravitreal ampicillin sodium for antibiotic-resistant endophthalmitis: streptococcus uberis first human intraocular infection report”. J Ophthalmol. 2014. doi:10.1155/2014/395480.

Huang WT, Chang LY, Hsueh PR, Lu CY, Shao PL, Huang FY, et al. Clinical features and complications of viridans streptococci bloodstream infection in pediatric hemato-oncology patients. J Microbiol Immunol Infect. 2007;40(4):349–54.

Acknowledgements

We thank Mark van der Linden and Matthias Imöhl, Institute of Medical Microbiology, National Reference Center for Streptococci, University Hospital RWTH Aachen, Aachen, Germany, for sodA sequencing of S. uberis.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

CV participated in clinical management and data collection. HD performed microbiological work-up and participated in preparation of the manuscript. KL participated in clinical management and drafted and wrote of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Rights and permissions

This article is published under an open access license. Please check the 'Copyright Information' section either on this page or in the PDF for details of this license and what re-use is permitted. If your intended use exceeds what is permitted by the license or if you are unable to locate the licence and re-use information, please contact the Rights and Permissions team.

About this article

Cite this article

Valentiny, C., Dirschmid, H. & Lhotta, K. Streptococcus uberis and Staphylococcus aureus forefoot and blood stream co-infection in a haemodialysis patient: a case report. BMC Nephrol 16, 73 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12882-015-0069-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12882-015-0069-6