Abstract

Background

Echocardiography (echo) is the primary imaging modality for infective endocarditis (IE). However, the recommendations on timing and mode selection for transesophageal echocardiography (TEE) and transthoracic echocardiography (TTE) vary across guidelines, which can be confusing for clinical decision makers. In this case, we aim to appraise the quality of recommendations by appraising the quality of various guidelines.

Methods

A search of guidelines containing recommendations for the appropriate use of echo in adult IE patients published in English between 2007 and 2019 was conducted. The APPRAISAL OF GUIDELINES FOR RESEARCH & EVALUATION II (AGREE II) instrument was applied independently by two reviewers to assess the integrated quality of the identified guidelines. The recommendations of concern are extracted from related chapters.

Results

A total of 9 guidelines met the criteria, with AGREE II scores ranging from 36 to 79%, and the domain of “stakeholder involvement” received the lowest score. The most contentious issue is whether a follow-up TEE is mandatory in uncomplicated native valve IE with an initial positive TTE. Conflicting recommendations are presented with a low evidence level based on little evidence.

Conclusions

In general, the recommendations proposed in the 9 identified guidelines on the appropriate use of echo are satisfying. The guideline quality score can be taken into account by the clinicians when evaluating the recommendations for clinical decisions. Additional studies with high evidence level should be conducted on the most controversial issues of whether a subsequent TEE is mandatory in uncomplicated native valve IE with an initial positive TTE.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Echocardiography (echo) is the primary imaging modality for infective endocarditis (IE). A positive echo is defined by vegetation or abscess, and new dehiscence of the prosthetic valve is included as a major modified Duke criterion along with positive microorganisms [1]. In addition, echocardiographic examination is also able to show haemodynamic severity of the valve lesion [2]. The appropriate use of echo should be cost-effective, time-efficient and focused on potential associated complications [3, 4]. Timely and accurate guidance should be available for the diagnosis and management of IE. As per a single-center study, a considerable number of transesophageal echocardiography (TEE) exams were rated as inappropriately used for IE [5]. Over the past 15 years, there have been 9 guidelines that cover IE diagnosis and contain evidence-based recommendations on the appropriate use of echo (all published in English, and the latest version of each guideline was considered). However, these guidelines differ in their recommendations on TEE and transthoracic echocardiography (TTE) application in certain clinical scenarios, which can be confusing for clinical decision makers. APPRAISAL OF GUIDELINES FOR RESEARCH & EVALUATION (AGREE) is an instrument for comprehensive guideline evaluation across 6 domains, including scope and purpose, stakeholder involvement, rigor of development, clarity of presentation, applicability and editorial independence. AGREE II, the updated version developed in 2013, updated certain items from the original version [6]. A systematic review of the appropriate use of echo based on critical assessment and the quality comparison of different guidelines was presented to allow clinicians to make better decisions in certain confusing clinical scenarios.

Methods

Search process

A literature search of current clinical practice guidelines that contain recommendations on IE imaging was conducted on PubMed, Embase, Web of Science and websites of guideline development societies (websites of organizations and societies are shown in Table S1); “adult” “infective endocarditis”, “echocardiography”, “transesophageal echocardiography” and “transthoracic echocardiography” were searched either singly or in combination (the detailed search strategy used is shown in Table S2). The search covered the guidelines published in English from 5 June 2007 to 5 July 2019.

Inclusion criteria

Guidelines that met the following criteria were included:

-

1.

Met the definition of a guideline given by The Institution of Medicine [7], which was described as “systematically developed statements to assist practitioner and patient decisions on appropriate healthcare for specific clinical circumstance”.

-

2.

Contained recommendations on the appropriate use of echo in the diagnosis, treatment, or follow-up process of IE.

-

3.

Targeted adult patients.

-

4.

Was the latest version with updated guidelines.

-

5.

Was free to access the full text.

-

6.

Was written in English, including translated versions of other languages.

Titles and abstracts were reviewed by 2 reviewers independently. After that, any disagreements were discussed and adjudicated through consensus with a third party. Finally, the final selection of guidelines was performed by the 2 reviewers together.

Guideline appraisal and recommendation extraction

A comprehensive evaluation was performed on the 9 selected guidelines across the 6 domains of the AGREE II instrument: i) scope and purpose, ii) stakeholder involvement, iii) rigor of development, iv) clarity of presentation, v) applicability, and vi) editorial independence. Two reviewers evaluated 23 items across 6 domains independently by providing scores ranging from 1 to 7, where 1 represents strong disagreement due to no relevant information given or the concept being barely addressed, and 7 represents strong agreement due to exceptional reporting quality or fully meeting the criteria of AGREE II. The final score for each domain was obtained by the calculation formula given by AGREE II: the scaled domain score = (obtained score – minimum possible score)/(maximum possible score – minimum possible score). If the difference between the scores given by both reviewers for a certain item was greater than 20% of the lower score, a third reviewer reviewed and evaluated the guidelines [8]. The guidelines with an average score higher than 60% were marked as “Strongly recommended”, those with scores ranging from 30 to 60% were marked as “Recommended with some modification”, and those with scores lower than 30% were marked as “Not recommended” [9].

Except for the guidelines of the Chinese Society of Cardiology, version 2015 and the Swedish Society of Infectious Diseases, version 2007 (CSC 2015, SSID 2007) without the report of Conflicts of Interest (COI) [10, 11], we calculated the proportion of panel members with an industrial relationship (RWI) with authors reported in other guidelines and analyzed the correlation between the RWI ratio and AGREE II score using SPSS 25.0. Statistical significance was indicated when α<0.05 [8].

All recommendations on the appropriate use of echo, including the timing and mode (TTE and TEE), were extracted from the relevant chapters. In an effort to avoid phrasing confusion, the recommendation class and level of evidence quoted from SSID 2007 were converted into a unified form that is consistent with those used in other guidelines [11]. The recommendation grade and level of evidence were coded as I/II/III and A/B/C, respectively.

Results

Guidelines that meet the criteria

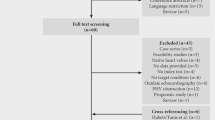

A total of 1015 records were searched during the literature search, and 1006 records were removed after the review of the title, abstract, and full text (Fig. 1). As the outcome, 9 guidelines reported by 8 host organizations (some of them were joint endeavors) met the including criteria: National Heart Association of Malaysia, version 2017 (NHAM 2017); American Heart Association, version 2015 (AHA 2015); European Society of Cardiology, version 2015 (ESC 2015); British Society for Antimicrobial Chemotherapy, British Heart Rhythm Society, version 2014, (BSAC/BHRS 2014); Japanese Circulation Society, version 2017, (JCS 2017); British Society for Antimicrobial Chemotherapy, version 2011 (BSAC 2011); Spanish Society of Infectious Diseases and Clinical Microbiology, version 2015 (SEIMC 2015); CSC 2015; and SSID 2007 [10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18]. The guidelines are shown in Table S3. The guideline identifiers, host organizations, regions, average AGREE II scores, COI, number of echo recommendations and RWIs are summarized in Table 1.

Guideline appraisal by AGREE II

The scores of each guideline are presented in the radar charts (Fig. 2) and Table S4. The AGREE II scores for all guidelines ranged from 36 to 79%, with a median of 55%; among them, 4 guidelines with scores higher than 60% (NHAM 2017, AHA 2015, ESC 2015, and BSAC/BHRS 2014) [12,13,14,15] were rated as “Strongly recommended”, while the others, with scores ranging from 36 to 55%, (JCS 2017, BSAC 2011, SEIMC 2015, CSC 2015, and SSID 2007) [10, 11, 16,17,18] were rated as “Recommended with some modifications”. No guideline had a score lower than 30% or rated as “Not recommended”. There was no item with a greater than 20% difference between the scores given by the two reviewers.

Rader charts of the AGREE II score distribution across 6 domains for the guidelines. The guidelines were divided into different charts by scale of aggregate score. AGREE II, appraisal of guidelines for research & evaluation. a Guidelines classified as “Strongly recommended”. b Guidelines classified as “Recommended with modification”

Domain1 (scope and purpose) includes items on the overall goal, the specific health issues contained in the guideline, and its target population. In contrast with other domains, guideline performance in this domain is nonspecific; that is, most of them generally summarized the concerning issues without any further elaboration. NHAM 2017, BSAC/BHRS 2014, and BSAC 2011 [12, 15, 17] specifically expounded on the items following the AGREE II rules, thus receiving relatively high scores.

Domain2 (stakeholder involvement) concerns whether the guideline was developed by appropriate stakeholders and whether the views of its intended users were considered. This domain received the lowest average score, with two-thirds of the guidelines were scoring no more than 33%. Only NHAM 2017, BSAC/BHRS 2014, and JCS 2017 [12, 15, 16] specified the department to which the clinical guideline applied for the specialists. In addition, patients as the target population was reported only by BSAC/BHRS 2014 [15] in the external review.

Domain 3 (rigor of development) comprises the processes of evidence synthesis, the formulation of the recommendations and update procedures. CSC 2015 and SSID 2007 [10, 11] reported no information on the selection of evidence, while BSAC/BHRS 2014, JCS 2017 and BSAC 2011 [15,16,17] provided little description of this subject. In addition, only AHA 2015, ESC 2015 [13, 14] and NHAM 2017 [12] privided updated statements or detailed information on external expert reviews. The narrative of methods for formulating the recommendations were relatively clear, resulting in high scores.

Domain 4 (clarity of presentation) involves the clarity of the description and the format of the guideline. The guidelines received the highest average scores in this domain, and the variation in the scores was the smallest among all domains.

Domain 5 (applicability) addresses practical implementation, efforts for improving uptake, and resource implications. Additional disseminating materials were provided by only NHAM 2017 ESC 2015 and AHA 2015 [12,13,14]. Few guidelines mentioned cost implications. However, the monitoring and auditing criteria were set precisely by all guidelines, with an average score higher than 80%.

Domain 6 (editorial independence) pertains to transparency declarations, including the funding body and competing interests of the members of the guideline-development group. Nor information on the funding body or its influence on the content was mentioned by JCS 2017, CSC 2015 or SSID 2007 [10, 11, 16]. In addition, no records on the disclosure of potential COI were mentioned by SSID 2007 [11] or CSC 2015 [10]. As a result, there was no correlation between RWI and AGGEE II score (Pearson’s correlation r = − 0.081 P = 0.863) for the rest of the guidelines.

More than half of the guidelines (5 out of 9) received scores lower than 60%. According to the independent-sample t-test, t’-test (editorial independence) and Wilcoxon rank-sum test (clarification of presentation), the guidelines classified as “Recommended with modification” were significantly different from those classified as “Strongly recommended” in the domains of “rigor of development” (P = 0.015), “applicability” (P = 0.005) and “editorial independence” (P = 0.024) (Fig. 3). With regard to specific items, 8 of the 9 guidelines received a score of zero on the “target population” item, which indicates that the guidelines generally failed to consider the view of patients in the recommendations.

Recommendations on appropriate use of echo

The recommendations for various clinical scenarios were organized and listed in Table S5 (recommendations with controversies) and Table S6 (recommendations without controversies). As shown in the tables, both consensus and controversy were present, and the consensus outweighed the controversy.

Seven of the 9 guidelines included recommendations on the first-line modality of suspected IE. Except for the contradictory and inconclusive statement of SSID 2007, all other guidelines (6 out of 7) agreed that TTE should be the first choice (class of recommendation: I, level of evidence: B-C).

Five of the 9 guidelines recommended further TEE, when first-line TTE is proven to be nondiagnostic due to its poor echocardiographic window, due to the higher sensitivity of TEE (class of recommendation: I, level of evidence: B-C) [1].

For patients with suspected IE under a prosthetic heart valve/intracardiac device, TEE was recommended by 5 of the 9 guidelines (class of recommendation: I, level of evidence: B-C). Furthermore, suggestions for patients with implantable cardiac electronic devices (ICEDs) were given by the guidelines of BSAC/BHRS 2014, recommending that echo should be conducted for patients with implantable cardiac electronic device lead infection (LCED-LI), implantable cardiac electronic device-associated native or prosthetic valve endocarditis (LCED-IE) and suspected generator pocked infection concurrent with ICED-LI or ICED-IE (level of evidence: B-C) [15].

Echo is recommended for patients with S. aureus bacteremia (SAB) by 7 of the 9 guidelines (class of recommendation: IIa, level of evidence: B-C).

Follow-up echo (no mode was specified) was advised by 5 of the 9 guidelines after the onset of a suspected IE (class of recommendation: I, level of evidence: B-C). Among them, ESC 2015 and CSC 2015 further specified the clinical manifestations of a complication include new murmur, embolism, persisting fever, heart failure, abscess, and atrioventricular block [10, 14], while SSID 2007 considered only new or progressive heart failure as an indication for a repeated echo [11].

For patients under medical therapy, 3 of the 9 guidelines recommended follow-up echo (class of recommendation: I-IIa, level of evidence: B-C). In addition, follow-up echo is recommended only for complicated IE in SSID 2007 (strength of evidence: II C) and IE with suspected development of complications in AHA 2015 (strength of evidence: I B). Moreover, SSID 2007 stated that TEE is not needed for uncomplicated IE or those with good response to treatment (strength of evidence: II C) [11, 13].

An intraoperative echo examination for IE patients requiring surgery was recommended by 3 of the 9 guidelines (class of recommendation: I, level of evidence: B-C) and was mentioned by BASC 2011 with no formal recommendation [17]. Moreover, BASC/BHRS 2014 mentioned that after IECD removal, patients need a follow-up echo to identify persisting vegetation (level of evidence: C) [15].

At the completion of antibiotic therapy, TEE is recommended by 6 of the 9 guidelines (class of recommendation: I-IIa, level of evidence: C).

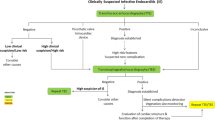

Regarding whether a follow-up TEE is needed for suspected IE with a positive TTE, the guidelines offered varied guidance based on the features of the target population. For example, BASC 2011 suggested that a positive TTE should be considered to indicate the need for a subsequent TEE, except the isolated right-sided native valve endocarditis (NVE) with good quality TTE examination (no formal recommendation formulated) [17]. ESC 2015 and JCS 2015 excluded unequivocally isolated right-sided native valve IE (class of recommendation: IIa, level of evidence: C) [14, 16]. NHAM 2017 and AHA 2015 advised TEE for patients under concern for complications. NHAM 2017 mentioned that a worsening clinical course and high predisposing risk should be included as indications for TEE (AHA 2015 has a strength of recommendation of I B, and no formal recommendation was given in NHAM 2017) [12, 13]. In addition, SSID 2007 and NHAM 2017 recommended not using TEE after a positive TTE for patients with uncomplicated NVE and low predisposing risk, as well as for patients who had a prompt response to treatment (SSID 2007 has a strength of recommendation of IIIc, and no formal recommendation was given in NHAM 2017) [11, 12]. In summary, as shown in the upper part of Figs. 3, 4 guidelines recommended TEE for all patients except those with isolated right-sided NVE [14, 16, 17], while other 3 guidelines recommended TEE examination only for those with suspected complications (defined differently between the guidelines as showed in Table S5) [11,12,13].

Flowcharts for the controversial clinical scenarios. The dotted box presents the recommendations of the dispute. The ratio marked on the arrow represents the number of guidelines that made the indicated recommendation. The level of recommendation is indicated in brackets. The darker the background color is in the box, the higher the average score of the guidelines that made the recommendation

As shown in the lower part of Fig. 4 and Table S5, when an initial TEE showed a negative result, for patients without a diagnosis of IE but with existing suspicion, 6 of the 9 guidelines recommended a subsequent TEE within a given time limit based on different guidelines (class of recommendation: I, level of evidence: B-C). However, the maximum time limit given by the guidelines varied from 5 to 10 days.

Discussion

This is the first time that the controversies among recommendations on the appropriate use of echo were evaluated using the AGREE II score of guidelines.

Of the 9 guidelines, the methodology sections of NHAM 2017 and BHRS 2014 indicated that the entire content was compiled based on the AGREE II principle, and both of these guidelines received a score higher than 60% [12, 15]. However, compared with other guidelines that failed to involve certain AGREE II items and thus obtained lower scores, the superior score of NHAM 2017 is largely due to a more general coverage of items rather than a higher grade for each item. The descriptions referring to Item 19 (facilitators and barriers to the application) and Item 20 (the potential resource) in NHAM 2017 were rather perfunctory and lacked in-depth content. Although AGREE II items are recommended during the development of guidelines, comprehensive coverage is just as important as the quality of coverage.

It should also be noted that some studies have shown that exposure to information provided directly by pharmaceutical companies is associated with higher prescribing frequency, higher costs and lower prescribing quality. Therefore, disclosure of potential COI could be necessary [19, 20]. However, it was found that there was no correlation between the proportion of RWI and the AGREE II score involved in the study. This outcome could have been obtained for a variety of reasons, i.e., some guidelines were found to have a high RWI thanks to a more thorough and accomplished disclosure process and less underreporting. For example, ESC has a very detailed COI appendix [14]. In contrast, only NHAM 2017 mentioned that there was no potential COI to disclose and no further detailed relevant content to present. In that case, it cannot be ruled out that the actual RWI proportion of its guideline committee members was concealed and underreported.

Based on the comparison of the recommendations and viewpoints presented by the guidelines, the algorithms for echo use were similar in most cases. Differing recommendations were mainly given on more specific clinical scenarios, and these recommendations were complementary and without conflict. However, there are 2 issues still up for debate.

TTE has been proven to have a sufficient negative predictive value for NVE in patients with low to intermediate risk when strict negative criteria were applied [21, 22]. For these low-risk patients stratified based on clinical judgment with negative TTE, evidence revealed and guidelines proposed that TEE was not necessary [10,11,12,13,14, 16, 17, 23,24,25]. For a first-line negative TTE with undiagnosed but high suspicion of IE, a follow-up TEE is fully agreed upon. However, the maximum time limits given by the guidelines varies from 5 to 10 days (Fig. 4, Table S5). As TEE may fail to detect abnormalities in the early stage, while the severity of pathology distinguished by echo is helpful for the determination of the following management strategy [26], conducting a follow-up TEE within the appropriate time window could be significant. A recent study has shown that an early (< 4 days) definitive echo is associated with fewer embolic events than echos administered later [27]. Therefore, combining the individual characteristics of each patient, a definitive echocardiogram that identifies the pathology of IE should be timely.

For the most controversial issue of whether a subsequent TEE is mandatory in uncomplicated NVE with initial positive TTE, ESC 2015, JCS 2017 and BASC 2011 recommended TEE for all patients except those with isolated right-sided NVE [14, 16, 17], while NHAM 2017, SSID 2007 and AHA 2015 recommended TEE examination only for those with suspected complications [11,12,13]. Therefore, for patients (with the exception of those with isolated right-sided NVE) with no or low risk of complications, which are not uncommon in clinical practice, it is unclear whether TEE examination is necessary. On the one hand, TEE is helpful in evaluating the presence of intracardiac complications, offering prognostic information and helping develop treatment plans. On the other hand, if an initial TTE clearly presents vegetation and the probability of complications is low (presented as a small aortic vegetation, mild aortic regurgitation, and normal left ventricular size and function), a subsequent TEE seems to have no incremental value for the treatment strategy [24], which may lead to the overuse of TEE. However, the recommendation that suggested a subsequent TEE after a positive TTE seemed to be less evidence-based and convincing, with a recommendation class of IIa which indicates that weight of evidence and opinion shows usefulness and/or effectiveness, and an evidence level of C which indicates only consensus of opinion. Similarly, the evidence strength of SSID 2007, which explicitly recommended that there was no need to repeat TEE, is C III, which indicates that the evidence supporting the recommendation is weak. Therefore, there is insufficient evidence on this issue, and additional studies with high evidence levels are needed in the future. In addition, isolated right-side NVE was excluded from the adapted population by ESC 2015, JCS 2017 and BASC 2011, which require a subsequent TEE examination as the right-sided structure is located anteriorly and thus closer to the TTE transducer than the transoesophageal transducer, which allows TTE to offer more valuable information. This was also because a subsequent TEE was found to have no additional value for providing new information in isolated right-sided NVE patients [28].

Conclusion

According to AGREE II and compared with guidelines classified as “Recommended with modification”, those guidelines classified as “Strongly recommended” were more rigorously developed, and the recommendations involved in these guidelines were of higher quality. Clinicians can rely on the guideline quality score when evaluating the recommendations for clinical decision making. In addition, it is also expected that updated to the guidelines will lead to better performance in the domain of “stakeholder involvement”. For the most contentious issue, i.e., whether a subsequent TEE is mandatory in uncomplicated NVE with initial positive TTE, related studies are rarely seen. Therefore, more research on this issue, especially studies with high evidence levels, is desired in the future.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- Echo:

-

Echocardiography

- IE:

-

Infective endocarditis

- TEE:

-

Transesophageal echocardiography

- TTE:

-

Transthoracic echocardiography

- AGREE:

-

APPRAISAL OF GUIDELINES FOR RESEARCH & EVALUATION

- CSC 2015:

-

Chinese Society of Cardiology, version 2015

- SSID 2007:

-

The Swedish Society of Infectious Diseases, version 2007

- COI:

-

Conflicts of Interest

- RWI:

-

The proportion of panel members with an industry relationship

- NHAM 2017:

-

National Heart Association of Malaysia, version 2017

- AHA 2015:

-

American Heart Association, version 2015

- ESC 2015:

-

European Society of Cardiology, version 2015

- BSAC/BHRS 2014:

-

British Society for Antimicrobial Chemotherapy, British Heart Rhythm Society, version 2014

- JCS 2017:

-

Japanese Circulation Society, version 2017

- BSAC 2011:

-

British Society for Antimicrobial Chemotherapy, version 2011

- SEIMC 2015:

-

Spanish Society of Infectious Diseases and Clinical Microbiology, version 2015

- ICED:

-

Implantable cardiac electronic device

- LCED-LI:

-

Implantable cardiac electronic device lead infection

- LCED-IE:

-

Implantable cardiac electronic device associated native or prosthetic valve endocarditis

- NVE:

-

Native valve endocarditis

References

Habib G, Badano L, Tribouilloy C, Vilacosta I, Zamorano JL, Galderisi M, Voigt JU, Sicari R, Cosyns B, Fox K, et al. Recommendations for the practice of echocardiography in infective endocarditis. Eur J Echocardiogr. 2010;11(2):202–19.

Cahill TJ, Prendergast BD. Infective endocarditis. Lancet. 2016;387(10021):882–93.

Hilberath JN, Oakes DA, Shernan SK, Bulwer BE, D'Ambra MN, Eltzschig HK. Safety of transesophageal echocardiography. J Am Soc Echocardiogr. 2010;23(11):1115–27 quiz 1220-1111.

Singh R, Naidu M, Bader Y, Freeman D, Zughaib M. Appropriate use of transesophageal echocardiogram for infective endocarditis: a single center experience. Cardiol Res Pract. 2019;2019:7670146.

Amuchastegui T, Hur DJ, Lynn Fillipon NM, Eder MD, Bonomo JA, Kim Y, McNamara RL, Malinis M, Sugeng L. An assessment of transesophageal echocardiography studies rated as rarely appropriate tests for infective endocarditis at an academic medical center. Echocardiography. 2019;36(11):2070–7.

Smith CA, Toupin-April K, Jutai JW, Duffy CM, Rahman P, Cavallo S, Brosseau L. A systematic critical appraisal of clinical practice guidelines in juvenile idiopathic arthritis using the appraisal of guidelines for research and evaluation II (AGREE II) instrument. PLoS One. 2015;10(9):e0137180.

Guidelines IoMUCoSfDTCP, Graham R, Mancher M. Clinical practice guidelines we can trust. Washington (DC): National Academies Press (US); 2011.

Ferket BS, Genders TS, Colkesen EB, Visser JJ, Spronk S, Steyerberg EW, Hunink MG. Systematic review of guidelines on imaging of asymptomatic coronary artery disease. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2011;57(15):1591–600.

He WM, Luo YT, Shui X, Liao XX, Liu JL, Zhuang XD. Critical appraisal of international guidelines on chronic heart failure: can China AGREE? Int J Cardiol. 2016;203:111–4.

Dong YG, Huang J, Li GH, Li LW, Li WM, Li XL, Liu XH, Liu ZY, Lu YX, Ma AQ, et al. Guidelines for the prevention, diagnosis, and treatment of infective endocarditis in adults. Eur Heart J. 2015;17(C):C1–C16.

Westling K, Aufwerber E, Ekdahl C, Friman G, Gardlund B, Julander I, Olaison L, Olesund C, Rundstrom H, Snygg-Martin U, et al. Swedish guidelines for diagnosis and treatment of infective endocarditis. Scand J Infect Dis. 2007;39(11–12):929–46.

National Heart Association of Malaysia, Academy of Medicine Malaysia. Clinical practice guidelines for the prevention, diagnosis & management of infective endocarditis. Putrajaya: Clinical Practice Guidelines (CPG) Secretariat; 2016.

Baddour LM, Wilson WR, Bayer AS, Fowler VG Jr, Tleyjeh IM, Rybak MJ, Barsic B, Lockhart PB, Gewitz MH, Levison ME, et al. Infective endocarditis in adults: diagnosis, antimicrobial therapy, and management of complications: a scientific statement for healthcare professionals from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2015;132(15):1435–86.

Habib G, Lancellotti P, Antunes MJ, Bongiorni MG, Casalta JP, Del Zotti F, Dulgheru R, El Khoury G, Erba PA, Iung B, et al. 2015 ESC guidelines for the management of infective endocarditis: the task force for the management of infective endocarditis of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). Endorsed by: European Association for Cardio-Thoracic Surgery (EACTS), the European Association of Nuclear Medicine (EANM). Eur Heart J. 2015;36(44):3075–128.

Sandoe JA, Barlow G, Chambers JB, Gammage M, Guleri A, Howard P, Olson E, Perry JD, Prendergast BD, Spry MJ, et al. Guidelines for the diagnosis, prevention and management of implantable cardiac electronic device infection. Report of a joint Working Party project on behalf of the British Society for Antimicrobial Chemotherapy (BSAC, host organization), British Heart Rhythm Society (BHRS), British Cardiovascular Society (BCS), British Heart Valve Society (BHVS) and British Society for Echocardiography (BSE). J Antimicrob Chemother. 2015;70(2):325–59.

Nakatani S, Ohara T, Ashihara K, Izumi C, Iwanaga S, Eishi K, Okita Y, Daimon M, Kimura T, Toyoda K, et al. JCS 2017 guideline on prevention and treatment of infective endocarditis. Circ J. 2019;83(8):1767–809.

Gould FK, Denning DW, Elliott TS, Foweraker J, Perry JD, Prendergast BD, Sandoe JA, Spry MJ, Watkin RW, Working Party of the British Society for Antimicrobial C. Guidelines for the diagnosis and antibiotic treatment of endocarditis in adults: a report of the Working Party of the British Society for Antimicrobial Chemotherapy. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2012;67(2):269–89.

Gudiol F, Aguado JM, Almirante B, Bouza E, Cercenado E, Dominguez MA, Gasch O, Lora-Tamayo J, Miro JM, Palomar M, et al. Diagnosis and treatment of bacteremia and endocarditis due to Staphylococcus aureus. A clinical guideline from the Spanish Society of Clinical Microbiology and Infectious Diseases (SEIMC). Enferm Infecc Microbiol Clin. 2015;33(9):625.e621–3.

Spurling GK, Mansfield PR, Montgomery BD, Lexchin J, Doust J, Othman N, Vitry AI. Information from pharmaceutical companies and the quality, quantity, and cost of physicians' prescribing: a systematic review. PLoS Med. 2010;7(10):e1000352.

Fickweiler F, Fickweiler W, Urbach E. Interactions between physicians and the pharmaceutical industry generally and sales representatives specifically and their association with physicians' attitudes and prescribing habits: a systematic review. BMJ Open. 2017;7(9):e016408.

Sivak JA, Vora AN, Navar AM, Schulte PJ, Crowley AL, Kisslo J, Corey GR, Liao L, Wang A, Velazquez EJ, et al. An approach to improve the negative predictive value and clinical utility of transthoracic echocardiography in suspected native valve infective endocarditis. J Am Soc Echocardiogr. 2016;29(4):315–22.

Leitman M, Peleg E, Shmueli R, Vered Z. Role of negative trans-thoracic echocardiography in the diagnosis of infective endocarditis. Isr Med Assoc J. 2016;18(7):407–10.

Connolly K, Ong G, Kuhlmann M, Ho E, Levitt K, Abdel-Qadir H, Edwards J, Chow CM, Annabi MS, Guzzetti E, et al. Use of the valve visualization on echocardiography grade tool improves sensitivity and negative predictive value of transthoracic echocardiogram for exclusion of native valvular vegetation. J Am Soc Echocardiogr. 2019;32(12):1551–1557.e1551.

Bai AD, Steinberg M, Showler A, Burry L, Bhatia RS, Tomlinson GA, Bell CM, Morris AM. Diagnostic accuracy of transthoracic echocardiography for infective endocarditis findings using transesophageal echocardiography as the reference standard: a meta-analysis. J Am Soc Echocardiogr. 2017;30(7):639–646.e638.

Bonzi M, Cernuschi G, Solbiati M, Giusti G, Montano N, Ceriani E. Diagnostic accuracy of transthoracic echocardiography to identify native valve infective endocarditis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Intern Emerg Med. 2018;13(6):937–46.

Thuny F, Di Salvo G, Belliard O, Avierinos JF, Pergola V, Rosenberg V, Casalta JP, Gouvernet J, Derumeaux G, Iarussi D, et al. Risk of embolism and death in infective endocarditis: prognostic value of echocardiography: a prospective multicenter study. Circulation. 2005;112(1):69–75.

Young WJ, Jeffery DA, Hua A, Primus C, Serafino Wani R, Das S, Wong K, Uppal R, Thomas M, Davies C, et al. Echocardiography in patients with infective endocarditis and the impact of diagnostic delays on clinical outcomes. Am J Cardiol. 2018;122(4):650–5.

San Román JA, Vilacosta I, Sarriá C, Garcimartín I, Rollán MJ, Fernández-Avilés F. Eustachian valve endocarditis: is it worth searching for? Am Heart J. 2001;142(6):1037–40.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank staff who developed the AGREE II instrument.

Funding

This study was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (81600206 to ZXD; 81870195 to LXX), and Natural Science Foundation of Guangdong Province (2016A030310140 to ZXD;20160903 to LXX; 20160904 to LDH). The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

PHX, XDZ, and XXL contributed to the study design. PHX and XDZ reviewed the guidelines, DDL re-examined the results, SZZ and MHL performed the statistical analysis, PHX and JL drafted the main manuscript and all authors reviewed and approved the final submitted manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no conflicts of interest or personal relationships.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1:

Table S1. Websites of organizations and societies.

Additional file 2:

Table S2. The detailed search strategy of databases.

Additional file 3:

Table S3. References of 9 included guidelines.

Additional file 4:

Table S4. The AGREE II scores of six domains for the included 20 guidelines.

Additional file 5:

Table S5. Recommendations with controversies.

Additional file 6:

Table S6. Recommendations without controversies.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Xie, P., Zhuang, X., Liu, M. et al. An appraisal of clinical practice guidelines for the appropriate use of echocardiography for adult infective endocarditis—the timing and mode of assessment (TTE or TEE). BMC Infect Dis 21, 92 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12879-021-05785-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12879-021-05785-6