Abstract

Background

HCV (Hepatitis C virus) is a prevalent chronic disease with potentially deadly consequences, especially for drug users. However, there are no special HCV or HIV (human immunodeficiency virus)-related intervention programs that are tailored for drug users in China; to fill this gap, the purpose of this study was to explore HCV and HIV-related knowledge among drug users in MMT (methadone maintenance treatment) sites of China and to investigate the effectiveness of HCV and HIV-related education for improving the knowledge of IDUs (injection drug users) and their awareness of infection.

Methods

The study was a randomized cluster controlled trial that compared a usual care group to a usual care plus HCV/HIV-REP (HCV/HIV-Reduction Education Program) group with a 24-week follow-up. The self-designed questionnaires, the HCV- and HIV-related knowledge questionnaire and the HIV/HCV infection awareness questionnaire, were used to collect the data. Four MMT clinics were selected for this project; two MMT clinics were randomly assigned to the research group, with subjects receiving their usual care plus HCV/HIV-REP, and the remaining two MMT clinics were the control group, with subjects receiving their usual care over 12 weeks. Sixty patients were recruited from each MMT clinic. A total of 240 patients were recruited. Follow-up studies were conducted at the end of the 12th week and the 24th week after the intervention.

Results

At baseline, the mean score (out of 20 possible correct answers) for HCV knowledge among the patients in the group receiving the intervention was 6.51 (SD = 3.5), and it was 20.57 (SD = 6.54) for HIV knowledge (out of 45 correct answers) and 8.35 (SD = 2.8) for HIV/HCV infection awareness (out of 20 correct answers). At the 12-week and 24-week follow-up assessments, the research group showed a greater increase in HCV−/HIV-related knowledge (group × time effect, F = 37.444/11.281, P < 0.05) but no difference in their HIV/HCV infection awareness (group × time effect, F = 2.056, P > 0.05).

Conclusion

An MMT-based HCV/HIV intervention program could be used to improve patient knowledge of HCV and HIV prevention, but more effort should be devoted to HIV/HCV infection awareness.

Trial registration

Protocols for this study were approved by institution review board (IRB) of Shanghai Mental Health Center (IRB:2009036), and registered in U.S national institutes of health (http://www.clinicaltrials.gov, NCT01647191). Registered 23 July 2012.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

HCV is a prevalent chronic disease with potentially deadly consequences. The global HCV positive prevalence is forecasted at 1.1% (0.9–1.4%), with an estimated population of 80 (64–103) million patients [1]. China also faces a similar situation, with an HCV prevalence among the general Chinese population varying from 0.43 to 2.2%, corresponding to a range of 6 million to 30 million people [2, 3]. High risk factors for HCV infection include injection drug use and transfusion of blood products [4]. Since a security system was established for blood donors in China, IDU has been the predominant mode of HCV transmission. According to the 2017 Annual Report on Drug Control in China, approximately 2.50 million drug users were documented in China at the end of 2016, but the actual number is estimated to be approximately 14 million [5]. Thus, it is not surprising that HCV infection prevalence among IDU in China is thought to be very high, ranging from 15.6 to 98.7% in different provinces [6].

Chronic HCV infection is associated with substantial morbidity and mortality. It is a major cause of liver and liver-related death, and HCV has surpassed HIV as a cause of death in the US [7, 8]. Globally, the burden of HCV infection is expected to substantially increase within the next few decades [9]. The development of chronic HCV infection may lead to progressive hepatic fibrosis, cirrhosis, and carcinoma [10]. However, most individuals who are infected with HCV are unaware of their infection because HCV can be asymptomatic for decades. Despite the serious consequences of HCV infection among IDUs, treatment uptake remains rather low, even in countries where the treatment is available and affordable [11]. A growing body of research has indicated that the barriers to treatment for HCV-positive drug users include limited knowledge, low risk awareness among patients and health service providers, discrimination of IDUs, and the high price of medication [12, 13]. Although the barriers for accessing treatment have been described, there is still a lack of evidence-based research to help guide future policy and treatment plans for drug users, especially in Asian countries. For example, even though in 2002 the U.S. National Institutes of Health (NIH) Hepatitis C Consensus Conference recommended treatment for HCV for IDUs to be determined on a case-by-case basis [14], this recommendation has not been followed by China. According to the Hepatitis C Prevention Guidelines in China [15], active drug users are excluded from antiviral treatment. Given the current situation in China and the high relapse rate among drug users, it is necessary to scale up education efforts to improve knowledge about HCV to help slow the progression of HCV in patients or to avoid infection in HCV-negative drug users.

A drug abuse treatment program has been shown to be a good platform to deliver HCV and HIV-related intervention or medical services. As a strategy for solving the problems of opiate abuse and HIV, the Chinese government established MMT clinics throughout the country starting in 2004. By the end of 2016, there were more than 760 MMT clinics in the country, and 300,000 heroin users benefit from this service [16]. MMT clinics have been shown to be an effective method to prevent the spread of HIV/AIDS [17, 18]. Given their same route of transmission and the situation in China, incorporating HCV prevention/intervention strategies into the MMT setting could be done more fully and effectively to prevent HCV-related complications and increase medical uptake.

At present, there are no special HCV and HIV-related intervention programs that have been tailored for drug users in China; to fill this gap, this cluster-randomized study was designed to explore the HCV- and HIV-related knowledge among drug users in MMT sites and to investigate whether an HCV and HIV intervention program was effective in improving their knowledge and infection awareness.

Methods

Study design

The study was a randomized cluster design with the MMT clinic as the unit of randomization to evaluate the efficacy of the intervention. Interested and eligible participant volunteers were invited into either the usual care group or the usual care plus HCV/HIV-REP (HCV/HIV-Reduction Education Program) group, depending on the randomization results. Four MMT clinics with similar demographic characteristics were selected for this study – two clinics for HCV/HIV-REP and two clinics for the usual care sites.

Usual care sites: Those in the usual care sites received standard procedures at the MMT for 12 weeks and were required to participate in follow-up interviews at the end of 12 weeks and 24 weeks after the intervention. The current standard for the usual care at an MMT includes a physical exam (including HIV testing, HCV testing, and urine testing for opiates) and weekly consultation. Patients were expected to take daily methadone under supervision.

HCV/HIV-REP sites: In addition to usual care services, the subjects in the HCV/HIV-REP sites received twelve 1.5-h sessions over 12 weeks based on the education materials that are described below.

Protocols for this study were approved by institution review board (IRB) of Shanghai Mental Health Center (IRB:2009036), and registered in U.S national institutes of health (http://www.clinicaltrials.gov, NCT01647191).

Participants and recruit procedures

The criteria of MMT clinics are as follows: (1) a minimum of 100 MMT patients in the clinic; (2) adequate space to accommodate the research assistants and study protocol procedures, including focus group discussions; (3) able to provide complete data on individual patients regarding their attendance and their HAV, HBV, HCV, HIV and other lab test results, which will be shared upon the patient’s consent.

In total, there are thirteen MMT clinics in Shanghai, and the research assistant contacted the directors of each MMT clinics via a call and explained the research contents to them. Eight MMT clinics meet the criteria mentioned above, and two of them expressed that they were not interested in attending this program. For convenience, we the excluded Baoshan and Jinshan MMTs because they are far from the research institutes. Finally, four MMT clinics were selected for this project (Xuhui MMT clinic, Minhang MMT clinic, Yangpu MMT clinic, and Hongkou MMT clinic); two MMTs were randomly assigned to the research group (HCV/HIV-REP sites) receiving standard methadone maintenance treatment plus HCV intervention for 12 weeks, and the remaining two MMT clinics were the control group (usual care sites) receiving standard methadone maintenance treatment.

Patients were recruited by posting advertisements at the MMT clinics, and the eligibility criteria included: (1) aged 18–65 years; (2) met DSM-IV (Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders-IV) criteria for heroin dependence; (3) consented to join this study and only participate this study; (4) signed informed consent. Individuals were excluded if they had any mental illness or organic disease that would prevent them from completing the survey or if they failed to attend therapy.

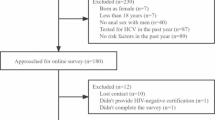

A total of 267 patients were invited to attend the screening interview, and 27 of them were excluded because they did not meet the inclusion criteria (n = 7), were incapable of completing the baseline survey (n = 13), or for other reasons (n = 7). A total of 221 patients and 194 patients attended the follow-up interview at the end of the 12th week and 24th week after the intervention (Fig. 1 flowchart).

Intervention

Develop the HCV/HIV-REP (HCV/HIV-reduction education program) protocol

Before the intervention, experts in both the addiction domain and the HCV domain were invited to discuss the contents of the intervention. Doctors and patients from MMT clinics were also consulted through focus interviews to understand their requirements. After the information collecting period, the principle investigator (PI) and research assistants made a draft of the intervention protocol based on the information that was collected from the focus group and experts. Five patients and five staff members were invited from the MMT clinics to pilot test the draft, to ensure they understand the contents of the protocol and allow them to provide suggestions or advice for the protocol. Finally, the research staff modified and finalized the drafts based on the suggestions from experts, MMT staff members, and patients.

Procedure

The HCV/HIV-REP was provided in the form of a group intervention. Approximately 15–20 patients were included in each session, which lasted 1.5 h. In the first 15 min, the participants were asked to recapitulate their last session, and in the last 15 min they were led to summarize the current day’s session. Another hour consisted of delivering education by a variety of learning techniques, including lectures, brainstorming, small and large group activities, individual worksheets, role-playing, and playing videos. For example, small teams of up to 5 participants conducted role-plays; large groups were assembled to encourage discussion about HCV/HIV-related risk reduction behaviors. Patients were encouraged to discuss issues related to each session’s topic. Pre- and posttraining tests were conducted via hard copy questionnaires at each session. The posttraining was conducted immediately after each session to evaluate the patients’ comprehension of the session. All of the educational programs were delivered by the PI and research assistant, who had extensive knowledge on drug abuse and the HCV/HIV education program. Each patient received RMB30 or its equivalent for compensation. In total, each participant in the research group received 12 interventions.

The contents of the education:

-

(1)

The liver and its function: Explain the anatomy of the liver and its function.

-

(2)

Types of hepatitis: Explain the types of hepatitis and the relationships of the different types.

-

(3)

HCV/HIV knowledge: Provide HCV/HIV-related knowledge about transmission routes, how to test for HCV/HIV, the genotype of HCV, and the possible outcomes of HCV infection.

-

(4)

Alcohol and HCV: Clarify how alcohol affects the risk of developing liver cancer for HCV-positive drug users.

-

(5)

HCV/HIV and risk behavior: Explain the risk behaviors that are related to HCV/HIV infection, including sharing needles and unprotected sexual behaviors and how to prevent risk behaviors during daily life.

-

(6)

HCV/HIV treatment: provide current treatment information for HCV/HIV infection, and how to deal with side effect.

-

(7)

HCV/HIV prevention and intervention: How to prevent HCV/HIV infection for HCV/HIV-negative drug users and how to slow the progression of disease.

-

(8)

HIV/HCV coinfection: Introduce the natural history of HIV/HCV coinfection and the impact of HIV on HCV infected patients.

-

(9)

Summary: Summarize the former topics, encourage the patients to discuss what they had learned, and address their questions.

Materials

The self-designed questionnaire

The demographic characteristics, including age, gender, education, marriage, and drug (alcohol) use history of each patient were collected via a self-designed questionnaire.

HCV-related knowledge questionnaire

This questionnaire was developed by the National Development and Research Institutes (NDRI) to assess the HCV related knowledge and attitude of the addicts and staffs with 20 items. The answer was “Yes”, “No” or “I don’t know,” and the score of the HCV-related knowledge was defined as the total number of correct responses. Specifically, “I don’t know” was defined as wrong. The instrument was translated into Chinese by one psychiatrist and back-translated by another psychiatrist and has been used in patients with a Chinese background. [19]

HIV related knowledge questionnaire

HIV knowledge were evaluated using a 45 items HIV Knowledge Questionnaires (HIV-K-Q) developed by Michael and his colleges in 1997 [20]. One point is given for each correct answer with a possible score ranging from 0 to 45.

HCV/HIV infection awareness

This is a self-rating questionnaire containing four questions: it’s impossible for me to be infected with HIV/HCV; it’s possible for me to be infected HIV/HCV; I might have sex with HIV/HCV-infected people; and maybe I have been infected with HIV/HCV. Each item is scored on a 1–5 Likert scale from “1 strongly disagree” to “5 strongly agree” with cumulative scores ranging from 0 to 20. The score of question 1 was reversed when the total scores were calculated.

Additional data to be collected

Research staff will obtain from clinic records information about HIV, HAV, HBV, and HCV antibody test results, treatment attendance, and other information relevant to this study for each participating subject.

Data analysis

Statistical Product and Service Solutions 20.0 (SPSS 20.0) was used to conduct statistical comparisons between control and intervention groups. The significance level was set at 0.05. A t test and a chi-square test were conducted to compare the demographic characteristics and the drug (alcohol) use history between the two clusters, investigating the success of the randomization. Independent t tests were used to compare the distribution of the continuous variables, and chi-square tests were used to compare the distribution of the categorical variables. The effectiveness of HCV-REP intervention on HIV/HCV knowledge and awareness of HIV/HCV infection were examined using linear mixed models. We included group (research and control), time (baseline, 12th week and 24th week), and time×group interaction, with the time×group interaction term indicating a differential change by group from baseline to the end of the trial. We also included the MMT clinics as random variables to include the cluster level effect.

Results

Baseline assessments and drug use history

A total of 267 MMT patients were recruited from the four selected MMT clinics, with 27 (10.1%) excluded due to different reasons (Fig. 1). A total of 19 subjects did not complete the 12-week follow-up assessment, and 46 subjects did not complete the 24-week follow-up assessment. There were no significant differences between those who did and did not complete the 12-week and 24-week follow-up interviews in terms of their age, gender, education, marriage, and length of receiving the methadone maintenance treatment.

A total of 240 MMT patients were recruited, and the average age was 42.46 (SD = 8.6); 192 (80%) patients were male, and 108 (45%) had medical insurance. The average duration of heroin use was 10.89 (SD = 6.42) years, and the average time they received MMT was 2.48 (SD = 1.36) years. A total of 80 (37.08%) patients used alcohol. In terms of HCV/HIV infection, 70% of patients (168) were HCV positive based on their medical records, and no participants were HIV positive. The average scores of HCV- and HIV-related knowledge was 6.51 (SD = 3.5) and 20.57 (SD = 6.54), respectively. There were no significant differences in the HCV/HIV infection or knowledge scores between the two groups, but we did observe significant differences in alcohol use and HIV/HCV infection awareness (Table 1).

Assessments at the 12-week and 24-week follow-up visits

-

(1)

HCV knowledge: The linear mixed models analysis revealed the main effects of group (F = 107.282, p < 0.001) and time (F = 77.672, p < 0.001), and a significant group x time interaction (F = 37.444, p < 0.001). The research group showed a greater increase in HCV knowledge.

-

(2)

HIV knowledge: The linear mixed models analysis revealed the main effects of group (F = 37.633, p < 0.001) and time (F = 15.441, p < 0.001), and a significant group x time interaction (F = 11.281, p < 0.001). Compared with the control group, the research group showed a greater increase in HIV knowledge.

-

(3)

HCV/HIV infection awareness: The linear mixed models analysis revealed the main effect of group (F = 13.496, p < 0.001), but no time effect (F = 0.246, p = 0.782) or group x time interaction (F = 2.056, p = 0.086) (Table 2).

Table 2 The effectiveness of intervention on HCV/HIV knowledge and HCV/HIV infection awareness (* p < 0.05, **p < 0.001)

Discussion

The HCV epidemic is an important problem that has been coined a viral time bomb. People who use injected drugs are heavily affected by this infectious disease. However, despite its high prevalence, HCV testing, prevention, assessment, and treatment in drug users remain suboptimal. A body of research has demonstrated that HCV education can reduce risk behaviors and disparities in HCV infection and influence a patient’s decision to explore and initiate antiviral treatment [21,22,23,24]. As the first randomized study among drug users in China, the study indicated that the high prevalence of HCV (70%) among drug users in MMTs in Shanghai was higher than the prevalence estimates of 67.0% from the meta-analyses among IDUs and 60.1% among IDUs in MMTs in China [25]; it was also higher than the global HCV prevalence among drugs users (67%) [26]. While the intervention outcomes are in line with our expectations that the knowledge of HIV and HCV increased, there were no changes in infection awareness after the intervention.

A body of research has indicated that behavior change is a complicated process that can be affected by many factors. According to the information–motivation–behavioral (IMB) skills model proposed by Fisher to explain the process of behavioral change, information or knowledge is defined as a ‘prerequisite’ for enacting a health behavior among three constructs (information or knowledge, motivation and behavioral skills) [27]. This means that, even though there were no actual behavior changes after the intervention, the improvements in HCV/HIV knowledge and willingness to change would act as positive factors to initiate the process of behavior changes in the patients.

At present, there is no vaccine that is currently available to prevent HCV infection. However, HCV is a preventable disease, especially for drug users. WHO guidance has indicated that the basic requirements for successful HCV prevention should provide drug users access to health care and justice, health literacy, and adapted services, and the key measurements for effective HCV prevention include needle exchange programs and opioid substitution programs [28]. In China, to solve the problems of HIV infection among IDUs, the government established the MMT program in 2004, but it does not appear to work for HCV prevention, based on the data of the HCV infection rate among MMT programs from 2004 to 2012 [25, 29]. Most researchers have pointed out that the combination of these two preventive steps at a high coverage could minimize the risk of HCV seroconversion by up to 75–80% [30, 31], but in China, only approximately 2% of IDUs have been able to access needle exchange programs [32], which may weaken the efficacy of MMTs on HCV infection prevention. Therefore, it is necessary to expand needle exchange programs to supplement MMTs in China.

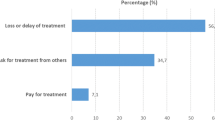

In the current study, the HCV infection rate was 70%, which means that medical treatment or related counseling for this group was needed. Researchers have suggested that it would be beneficial for HCV positive clients to receive treatment for HCV at their MMT program [33, 34], but cost is a significant barrier to them because both HCV treatment and MMT programs are not free in China. Given the poor living conditions of drug users, it is almost impossible for them to afford this medical expense. Moreover, active drug users are excluded from antiviral treatment, according to the Hepatitis C Prevention guidelines in China [35]; this exclusion provides another barrier from the government level and explains why, even though medication to treat the virus is available, many drug users have been unable to reap the benefits of HCV treatment. Other barriers include limited knowledge, lack of empirical data in the current study, and being unable to confirm the barriers and problems in accessing HCV-related treatment in this group. Under this condition, providing education and improving the knowledge level should be an appropriate strategy to slow the progression of HCV infection.

We acknowledge a number of limitations in the study: first, since all of the participants were recruited from MMT clinics, dissemination of the results should be done with caution. Future studies may involve a randomization study in other treatment sites or areas. Second, a quantitative study cannot define the barriers for accessing HCV treatment in this group, so a future study should combine quantitative and qualitative research. Finally, due to self- reported data, the recall bias could be as a confounding factor for the outcomes.

Conclusion

An MMT-based HCV/HIV intervention program could be used to improve patient knowledge of HCV and HIV prevention, but more effort will need to be devoted to HIV/HCV infection awareness. Overall, this pilot study confirmed the effects of HCV- and HIV-related intervention among drug users in MMT programs in China, which have been defined as situations for delivering HCV/HIV intervention; although there are limitations in the current study, it still provided evidence-based support for China and other Asian countries for how to deliver HCV- and HIV-related interventions based on the MMT programs.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets generated and analyzed during the current study are not publicly available due to the conflict with patients’ privacy (it was not in accordance with patients’ written informed consent) but are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- HCV:

-

hepatitis C virus

- HCV/HIV-REP:

-

HCV/HIV-reduction education program

- HIV:

-

human immunodeficiency virus

- IDU:

-

injection drug user

- IRB:

-

institution review board

- MMT:

-

methadone maintenance treatment

- NIH:

-

the U.S national institutes of health

- US:

-

the United States

References

Gower E, Estes C, Blach S, Razavishearer K, Razavi H. Global epidemiology and genotype distribution of the hepatitis C virus infection. J Hepatol. 2014;61:45–57.

Cui Y, Jia J. Update on epidemiology of hepatitis B and C in China. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2013;28(1):7–10.

Jian L, Zhou Y, Lin X, Jiang Y, Tian R, Zhang Y, Wu J, Zhang F, Zhang Y, Wang Y, Bi S. General epidemiological parameters of viral hepatitis a, B, C, and E in six regions of China: a cross-sectional study in 2007. PLoS One. 2009;4(12):e8467.

Sy T, Jamal MM. Epidemiology of hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection. Int J Med Sci. 2006;3(2):41–6.

National Drug Control Committee. Annual report on drug control in China, 2017. Beijing, China: National Drug Control Committee; 2017. http://www.nncc626.com/2017-03/23/c_129516372.htm

Xia X, Luo J, Bai J, Yu R. Epidemiology of hepatitis C virus infection among injection drug users in China: systematic review and meta-analysis. Public Health. 2008;122(10):990–1003.

Hajarizadeh B, Grebely J, Dore GJ. Epidemiology and natural history of HCV infection. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2013;10(9):553–62.

Ly KN. HCV surpassed HIV as cause of death among Americans. Infectious Disease News. 2012;25(3):15.

Razavi H, Waked I, Sarrazin C, et al. The present and future disease burden of hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection with today's treatment paradigm. J Viral Hepat. 2014;21(l):34–59.

van der Meer AJ, Veldt BJ, Feld JJ, Wedemeyer H, Dufour J-F, Lammert F, Duarte-Rojo A, Heathcote EJ, Manns MP, Kuske L, Zeuzem S, Hofmann WP, de Knegt RJ, Hansen BE, Janssen HLA. Association between sustained virological response and all-cause mortality among patients with chronic hepatitis C and advanced hepatic fibrosis. JAMA. 2012;308(24):2584–93.

Grebely J, Matthews GV, Lloyd AR, Dore GJ. Elimination of hepatitis C virus infection among people who inject drugs through treatment as prevention: feasibility and future requirements. Clin Infect Dis. 2013;57(7):1014–20.

Harris M, Rhodes T. Hepatitis C treatment access and uptake for people who inject drugs: a review mapping the role of social factors. Harm Reduct J. 2013;10:7.

Mravčík V, Strada L, Štolfa J, et al. Factors associated with the uptake, adherence and efficacy of hepatitis C treatment among people who inject drugs: a literature review. Patient Prefer Adherence. 2013;7:1067–75.

NIH Consens State Sci Statements. NIH consensus statement on management of hepatitis C: 2002. NIH consensus and state-of-the-science statements. 2002;19(3):1–46.

Chinese Society of Hepatology. Hepatitis C prevention guideline in China. Chin J Hepatol. 2004;l2(4):194–8.

National Center for AIDS/STD Control and Prevention, China CDC. Update on the ADIS/STD epidemic in China and main response in control and prevention in december,2016. Chinese Journal of AIDS & STD. 2016;4(22):549.

Wu ZY, Luo W, Sullivan S, Rou K, Lin P, Liu W, Ming Z. Evaluation of a needle social marketing strategy to control HIV among injecting drug users in China. AIDS. 2007;21(8):115–S122.

Qian HZ, Schumacher JE, Chen HT, Ruan YH. Injection drug use and HIV/AIDS in China: review of current situation, prevention and policy implication. Harm Reduct J. 2006;3(4):28–42.

Du J, Wang Z, Zhang HH, Dong AZ, Fan CL, Yuan Y, Jiang HF, Zhao M. HCV knowledge and HCV infection among drug users treated in a methadone maintenance treatment clinic. Chinese Journal of Drug Dependence. 2009;18(6):495–9.

Michael PC, Morrison D, Blair TJ. The HIV-knowledge questionnaire: development and evaluation of a reliable, valid and practical self-administered questionnaire. AIDS Behav. 1997;1:61–74.

Zule WA, Costenbader EC, Coomes CM, Wechsberg WM. Effects of a hepatitis C virus educational intervention or a motivational intervention on alcohol use, injection drug use, and sexual risk behaviors among injection drug users. Am J Public Health. 2009; 99,1(1):180–186.

Kapadia F, Latka MH, Hagan H, Golub ET, Campbell JV, Coady MH, Garfein RS, Thomas DL, Bonner S, Thiel T, Strathdee SA. Design and feasibility of a randomized behavioral intervention to reduce distributive injection risk and improve health-care access among hepatitis c virus positive injection drug users: the study to reduce intravenous exposures (strive). J Urban Health. 2007;84(1):99–115.

Stein MD, Herman DS, Anderson BJ. A trial to reduce hepatitis C seroincidence in drug users. J Infect Dis. 2009;28(4):389–98.

Norden L, Saxon L, Kåberg M, Käll K, Franck J, Lidman C. Knowledge of status and assessment of personal health consequences with hepatitis C are not enough to change risk behaviour among injecting drug users in Stockholm County. Sweden Scandinavian Journal of Infectious Diseases. 2009;41(10):727–34.

Wang C, Shi CX, Rou K, Zhao Y, Cao X, Luo W, Liu E, Wu Z. Baseline HCV Antibody prevalence and risk factors among drug users in China’s National Methadone Maintenance Treatment Program. PLoS One. 2016;11(2):e0147922.

Nelson P, Mathers B, Cowie B, Hagan H, Jarlais DD, Horyniak D, Degenhardt L. The epidemiology of viral hepatitis among people who inject drugs: results of global systematic reviews. Lancet. 2011;378(9791):571–83.

Fisher JD, Fisher WA, Bryan AD, Misovich SJ. Information-motivation-behavioral skills model-based HIV risk behavior change intervention for inner-city high school youth. Health Psychol. 2002;21(2):177–86.

Slomski A. WHO issues guidelines on HCV amid drug cost controversy. JAMA. 2014;311(22):2262–3.

Xun Z, Liang Y, Chow EPF, Wang Y, Wilson DP, Zhang L. HIV and HCV prevalence among entrants to methadone maintenance treatment clinics in China: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Infect Dis. 2012;12(1):130.

Hagan H, Pouget ER, Jarlais DCD. A systematic review and meta-analysis of interventions to prevent hepatitis C virus infection in people who inject drugs. J Infect Dis. 2011;204(1):74–83.

Martin NK, Hickman M, Hutchinson SJ, Goldberg DJ, Vickerman P. Combination interventions to prevent HCV transmission among people who inject drugs: modeling the impact of antiviral treatment, needle and syringe programs, and opiate substitution therapy. Clin Infect Dis. 2013;57(2):39–45.

Hammett T, Wu Z, Duc TT, Stephens D, Sullivan S, Liu W, Chen Y, Ngu D, Des Jarlais DC. Social Evils’ and harm reduction: the evolving policy environment for human immunodeficiency virus prevention among injection drug users in China and Vietnam. Addiction. 2008;103(1):137–45.

Alavian SM, Mirahmadizadeh A, Javanbakht M, Keshtkaran A, Heidari A, Mashayekhi A, Salimi S, Hadian M. Effectiveness of methadone maintenance treatment in prevention of hepatitis C virus transmission among injecting drug users. Hepat Mon. 2013;13(8):e12411.

Mukherjee TI, Pillai V, Ali SH, Altice FL, Kamarulzaman A, Wickersham JA. Evaluation of a hepatitis C education intervention with clients enrolled in methadone maintenance and needle/syringe programs in Malaysia. The International journal on drug policy. 2017;47:144–52.

Chinese Society Hepatology and Chinese Society of Infectious Diseases. The guideline of prevention and treatment for hepatitis C: a 2015 update. Beijing, China: Chinese Medical Association; 2015. http://cssld.ashermed.com/uploads/soft/160510/1-160510150J3.pdf

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to thank the participants and study team in Mental Health Center of Jiading, Yangpu, Hongkou, and Xuhui District in Shanghai, China.

Funding

This study was supported in the design of the study by a grant from Shanghai Municipal Education Commission—Gaofeng Clinical Medicine Grant Support (20152235), National Key R&D Program of China (2017YFC1310400), National Natural Science Foundation of China (U1502228, 81771436), and was supported in the data collection and analysis by Shanghai Municipal Health and Family Planning Commission joint research project (2014ZYJB0002), Shanghai Key Laboratory of Psychotic Disorders (13DZ2260500), Program of Shanghai Academic Research Leader (17XD1403300), key subject of Shanghai Municipal Health and Family Planning Commission(Psychiatry) (2017ZZ02021), Key Subject Construction of Jiading District Mental Health (JDYXZDZK-3).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

JYZ conducted the data analysis and drafted the manuscript. ZBL interviewed participants, collected and organized the primary data. LZ, JW, LPH, and GlZ participated in recruiting participants and collecting data in Mental Health Center of Jiading, Yangpu, Hongkou, and Xuhui District respectively. ZL helped in recruited participants and selected MMT sites. MZ made contribution to the conception of the study, MZ also provided suggestions and advice as a consultant. JD designed the study and revised the manuscript. All authors have approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The institution review board (IRB) of Shanghai Mental Health Center approved the study (IRB:2009036). The written informed consent was obtained from all participants before being recruited for the study. All experiments were in compliance with the Helsinki declaration.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhang, J.Y., Li, Z.B., Zhang, L. et al. DOES IT WORK? -a randomized controlled trial to test the efficacy of HCV and HIV-related education on drug users in MMT, China. BMC Infect Dis 19, 774 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12879-019-4421-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12879-019-4421-5