Abstract

Background

Up to one third of HIV-infected individuals with suspected TB are sputum-scarce. The Alere Determine™ TB LAM Ag lateral flow strip test can be used to diagnose TB in HIV-infected patients with advanced immunosuppression. However, how urine LAM testing should be incorporated into testing algorithms and in the context of specific patient sub-groups remains unclear.

Methods

This study represents a post hoc sub-group analysis of data from a randomized multi-center parent study. The study population consisted of hospitalized HIV-infected patients with suspected TB who were unable to produce sputum and who underwent urine LAM testing. The diagnostic utility of urine LAM for TB in this group was compared to the performance of urine LAM in patients who did produce a sputum sample in the parent study.

Results

There were a total of 187 and 2341 patients in the sputum-scarce and sputum-producing cohorts, respectively. 80 of the sputum-scarce patients underwent testing with urine LAM. In comparison to those who did produce sputum, sputum-scarce patients had a younger age, a lower Karnofsky performance score, and a lower weight and BMI at admission. A greater proportion of sputum-scarce patients were urine LAM positive, compared to those who were able to produce sputum (31% vs. 21%, p = 0.04). A higher proportion of sputum-scarce patients died within 8 weeks of admission (32% vs. 24%, p = 0.013). We inferred that 19% of HIV-infected sputum-scarce patients suspected of TB were diagnosed with tuberculosis by urine LAM testing, with an estimated positive predictive value of 63% (95% CI 43–82%).

Conclusions

Urine LAM testing can effectively identify tuberculosis in HIV-infected patients who are at a higher risk of mortality yet are unable to generate a sputum sample for diagnostic testing. Our findings support the use of urine LAM testing in sputum-scarce hospitalized HIV-infected patients, and its incorporation into diagnostic algorithms for this patient population.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Despite many recent advances in the diagnosis of tuberculosis (TB), it is estimated that one third of all TB cases are missed (either not diagnosed or not reported) [1, 2]. Current diagnostic tests for pulmonary TB rely on generation of a sputum sample. Historically, sputum microscopy, where sputum is examined under microscopy for acid-fast bacilli, has been the first-line test for TB. The World Health Organization (WHO) now advocates for the Xpert MTB/RIF test, an automated real-time polymerase chain reaction assay for detection of M. tuberculosis and rifampicin resistance, [3] as the initial diagnostic test for all adults and children with suspected TB [4]. The Xpert MTB/RIF test has demonstrated improved accuracy over smear microscopy, and has resulted in an improvement in time to treatment initiation for TB patients [5, 6]. However, despite allowing for more rapid diagnostic results as well as information on first line drug resistance, the Xpert MTB/RIF assay also requires the patient to generate a sputum sample of adequate quality and volume for this test to yield a result.

The HIV epidemic has changed the face of tuberculosis, particularly in Africa, where nearly 40% of active TB cases are co-infected with HIV [2]. In this population, TB often does not produce cavities and sputum has a low bacillary load [7], rendering a significant proportion of patients smear-negative [8,9,10], and up to a third of patients unable to produce sputum for diagnostic testing [11]. Various methods of sputum acquisition including sputum induction and bronchoscopy have been tested in this population, but these methods are expensive and require special facilities [12, 13]. Additionally, they require significant processing time and often do not provide same-day diagnosis, which has particular relevance in high-burden settings where many patients fail to return for results and are therefore often lost to follow-up [14]. Moreover, in hospitalized HIV-infected patients, post-mortem studies have illustrated a large burden of undiagnosed TB [15], and in this population rapid initiation of TB treatment may reduce mortality [1, 16, 17].

Lipoarabinomannan (LAM), an immunogenic glycolipid component of the bacterial cell wall excreted in the urine, offers a unique method for detection of M. tuberculosis [18,19,20] and has been recently shown to reduce mortality in hospitalized HIV patients when used to guide TB treatment initiation [21]. Urine LAM testing would likely have particular utility in HIV patients who are unable to produce a sputum sample, as urine specimens are generally easily obtained. Although the WHO has published guidelines about the use of urine LAM, they do not address how the test should be used in diagnostic algorithms when alternative tests are available (ex. Xpert MTB/RIF, smear microscopy, culture, etc.), or which patient sub-groups would benefit from specific first-line testing strategies [22]. To our knowledge, the performance of urine LAM specifically in sputum-scarce HIV patients has not previously been evaluated. To address this knowledge gap, we evaluated the diagnostic utility of urine LAM testing in a cohort of hospitalized HIV-infected patients unable to generate an adequate sputum sample for conventional TB testing.

Methods

Study design

This study represents a post hoc sub-group analysis of data from a pragmatic, randomized, parallel arm, multi-center study with stratified randomization by country. The primary analysis has already been reported [21]. The study was approved by the appropriate national regulatory authorities and by the University of Cape Town Human Research Ethics Committee. All patients provided informed written consent in their first language. This trial was registered with Clinicaltrials.gov (https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT01770730).

Patient enrollment and randomization

Patients admitted to ten urban or peri-urban hospitals in South Africa, Tanzania, Zambia and Zimbabwe were screened for study inclusion. A detailed description of hospital care, HIV and TB prevalence, routine clinical care, and the diagnostics infrastructure at each hospital are previously reported. [21] The inclusion criteria included: i) HIV-infected persons; ii) at least one of the following symptoms: current fever or cough, drenching night sweats, or self-reported loss-of-weight; iii) illness severe enough to necessitate hospitalization; iv) age ≥ 18 years; v) granting of informed consent. The exclusion criteria included: i) patients receiving any anti-TB medication in the 60 days prior to testing, and ii) unable to provide at least 30mls urine. Eligible patients were randomized to receive standard available TB diagnostics at each center or standard TB diagnostics plus adjunctive LAM, using centralized computer-generated allocation lists, stratified by country. The patients and the study team were not masked to both allocation and test results. In addition to a urine specimen, patients were asked to expectorate a minimum of two sputa for routine TB diagnosis. For patients unable to self-expectorate, sputum induction was employed. Clinical assessment by the attending physicians and chest x-ray (CXR) facilities were available in most cases, however additional radiology and non-sputum sampling was differentially available in study hospitals and requesting these investigations was at the discretion of the attending clinical team. For patients in the study arm, Alere Determine™ TB LAM Ag lateral flow strip test testing was performed at the bedside, according to manufacturer’s instructions. A grade 2 cutoff point or higher was deemed as a positive urine LAM result. The attending clinical team made all decisions regarding patient therapy and initiation of anti-TB treatment and the timing thereof, including acting upon the LAM test results. The WHO guidelines for the treatment of smear-negative tuberculosis were routinely used at study hospitals.

Outcomes and statistical analysis

The goal of this analysis was to assess the diagnostic utility of urine LAM for TB in HIV-infected patients admitted for suspected TB and who were unable to produce an adequate sputum sample. As no reference standard exists for the diagnosis of TB in the absence of a sputum sample, the findings of the LAM test were compared to the performance in patients who did produce a sputum sample in this study. Exact binomial 95% confidence intervals were calculated for proportions, and differences in proportions were calculated with 95% confidence intervals (using a normal-approximation) for comparisons between the groups. For categorical variables, differences between groups were evaluated using chi-square tests. For continuous variables, differences in means were calculated and t-tests were employed to evaluate differences in means between groups (applying the central-limit theorem to non-normal distributions).

Results

Patients

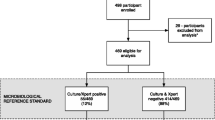

Of the 2528 patients enrolled in the study, a total of 222 patients did not have a sputum result. 35 of these patients generated a sputum sample but no result was recorded; therefore, these patients were not included in the sputum-scarce cohort. The remaining 187 patients (7.4% of the randomized patients) were unable to produce a sputum sample despite the availability of sputum induction facilities at all hospital sites.

Baseline characteristics

In this sputum-scarce cohort of 187 patients, the mean age was 36 years and 51% were female. In comparison to those who did produce a sputum sample, there was evidence that these patients were younger, had a lower Karnofsky performance score, and had a lower weight and BMI at admission (Table 1). In addition, there was evidence of an association with being unable to produce sputum and recruitment from Zambia, as a disproportionate number of sputum-scarce patients were recruited from this site. There was no evidence of a difference in baseline CD4+ count (Table 1).

Outcomes

Among the sputum-scarce cohort of 187 patients, 80 patients were assigned to the LAM study arm of the parent study and had urine LAM testing performed. A greater proportion of patients in this group were urine LAM positive, compared to those who were able to produce a sputum sample (31% vs. 21%, p = 0.04, Table 2). In addition, a greater proportion of patients underwent CXR (88% vs. 55%, p < 0.001) and were felt by the treating clinician to have a CXR suggestive of tuberculosis, compared to those who produced sputum (59% vs. 48%, p = 0.010). However, there was no evidence that the proportion of patients who received treatment for TB varied by the ability to produce a sputum sample (48% vs. 49%, p = 0.68). A higher proportion of those unable to produce sputum died within 8 weeks of admission (32% vs. 24%, p = 0.013).

Due to the lack of a reference standard for the diagnosis of TB in patients who cannot produce sputum, we used the diagnostic accuracy of urine LAM testing in those able to produce sputum and applied the false-positive rate to this cohort (using sputum culture positivity as the reference standard for the diagnosis of TB). This assumes the specificity of the urine LAM test does not differ among the patient populations that are able and unable to produce sputum, as CD4+ counts did not differ between these groups. Among those who were able to produce sputum, were sputum culture negative, and underwent LAM testing, 11.8% were found to have a positive urine LAM result (100/848, 95% CI 9.6–14.1%), which we considered the false positive rate of the test. Among those unable to produce sputum and who underwent a urine LAM test, 31% were found to have a positive urine LAM test (25/80, 95% CI 21%–43%). The difference between these two proportions was used to estimate the true positive rate of urine LAM testing in those unable to produce a sputum sample, and was estimated at 19% (95% CI 9.0–30%); i.e. 19% of HIV-infected patients suspected of TB but unable to produce a sputum specimen are diagnosed with TB with the use of a urine LAM test. Under these assumptions, the positive predictive value of a positive urine LAM test in this cohort is estimated as 63% (95% CI 43–82%).

Discussion

In this study, we identified a group of hospitalized, HIV-infected, sputum-scarce patients in whom diagnosis of tuberculosis was particularly challenging, and in whom a missed diagnosis could have had fatal consequences. Compared to the larger cohort of patients with suspected TB who were able to provide a sputum sample for diagnostic testing, this group had a lower weight and Karnofsky performance status, illustrating significant chronic illness and functional impairment. Sputum-scarce patients had a higher proportion of urine LAM test positivity as well as a significantly higher mortality at 8 weeks post-hospitalization. We estimate that urine LAM correctly identified TB disease in nearly 20% of these patients, in whom a diagnosis of tuberculosis would otherwise have been potentially impossible without more invasive testing, and many of whom may not have been empirically treated for TB as inferred from published post-mortem studies [15, 23,24,25]. Interestingly, in our study, there was no concordance between CXR and urine LAM results, highlighting the difficulty in using CXR alone as a diagnostic modality in HIV-infected individuals given the wide array of chest pathology often seen in this patient population.

Our results illustrate the capability of urine LAM as a point-of-care test to diagnose TB in sputum-scarce patients. While it is now understood that a very high burden of undiagnosed tuberculosis exists in hospitalized HIV-infected patients [15], very little is known about those who are unable to produce a sputum sample, and as they are generally excluded from clinical studies, data on this group is limited. Certainly, smear negative TB patients are known to have significant diagnostic delays as well as greater morbidity and mortality compared to smear positive patients, in whom a diagnosis can more easily be achieved [26,27,28] and in this population, urine LAM used in conjunction with sputum smear microscopy has demonstrated benefit in diagnosing culture-confirmed TB [29]. The diagnostic accuracy of urine LAM is greatest in HIV-infected patients with advanced immunosuppression, likely representing disseminated TB and renal involvement of tuberculosis. [30] This study highlights the value of urine LAM in this population who, due to an inability in producing a sputum specimen, would otherwise remain undiagnosed and as a consequence, likely have a higher mortality.

In resource-limited settings, many such patients are started on empiric TB treatment, a strategy that is supported by the World Health Organization for resource-constrained areas with a high HIV prevalence. [31] However, this may unnecessarily expose patients to a long course of potentially toxic treatment, and although this strategy has recently demonstrated a potential survival benefit [32], it preceded the widespread availability of other diagnostic tools such as Xpert MTB/RIF testing. Even worse, patients often do not receive empiric treatment, evidenced by post-mortem studies demonstrating that up to 50% of patients with autopsy evidence of tuberculosis are not on treatment for TB at the time of death. [23] Our results suggest that urine LAM testing could add an important tool in the diagnostic armamentarium permitting diagnosis and appropriate treatment in hospitalized HIV-infected patients who are sputum-scarce.

Although sputum could not be obtained in only 7.4% of the patients randomized in the parent study, this is likely an underestimate of the problem of sputum scarcity in HIV-infected patients, since sputum induction facilities were available at all recruitment sites as part of the study protocol. A higher proportion of HIV-infected patients presenting to hospital with symptoms of tuberculosis are likely to be sputum-scarce [12], and in most resource-limited settings where induction facilities are unavailable, urine LAM may have broader applications. In addition, 12.3% of patients screened for inclusion into the parent study were too sick to provide informed consent, and therefore were excluded from study participation. This group of patients were likely to have also been too sick to provide sputum samples for diagnostic testing, and thereby represent an additional population in whom urine LAM may be most beneficial in achieving a diagnosis of TB.

To our knowledge, this is the first study to demonstrate the utility of urine LAM testing in patients with suspected TB who are unable to provide a sputum sample for diagnostic testing. The implications of this finding are important – sputum-scarce patients present a significant challenge to clinicians and TB control programs alike, and highlight deficiencies in current diagnostic algorithms that rely on a patient’s ability to generate a sputum sample. Urine LAM testing in this group may facilitate rapid diagnosis of tuberculosis and enable prompt treatment initiation in this very vulnerable group of patients. It also has implications for designing diagnostic algorithms when both Xpert MTB/RIF and urine LAM are available, as is the case in many TB and HIV endemic countries, and suggests that urine LAM should be the first port of call in sputum-scarce patients. Thus, our findings inform clinical practice and patient management strategies.

This study has some important limitations. The cohort of patients unable to generate a sputum sample was small, and a majority of the sputum-scarce patients were disproportionately recruited in selected countries, which could reflect local problems with sputum collection and induction facilities. However, patients in the sputum-scarce cohort had different clinical characteristics compared to the larger group of patients who were able to provide a sputum sample, suggesting that this group truly represents a unique subset of patients. In order to calculate the positive predictive value of urine LAM in the sputum-scarce group, we had to make the assumption that the specificity of the urine LAM test does not differ between patients who are able and unable to produce sputum.

Conclusions

This study estimates that urine LAM testing has a high positive predictive value in hospitalized HIV-infected patients who are unable to generate sputum, and that urine LAM may identify patients with TB who would otherwise be missed and who have a high mortality. This point-of-care test acts as a powerful tool to aid the diagnosis of TB in a particularly challenging and vulnerable patient group, in whom a missed diagnosis has fatal consequences. This study supports the use of urine LAM testing in sputum-scarce, hospitalized HIV-infected patients, and should appropriately be incorporated into diagnostic algorithms.

Abbreviations

- BMI:

-

body mass index

- CXR:

-

chest x-ray

- HIV:

-

human immunodeficiency virus

- LAM:

-

lipoarabinomannan

- TB:

-

tuberculosis

- WHO:

-

World Health Organization

References

Dheda K, Barry CE 3rd, Maartens G. Tuberculosis. Lancet. 2016;387(10024):1211–26.

WHO. Global Tuberculosis Report. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2015.

Helb D, Jones M, Story E, Boehme C, Wallace E, Ho K, Kop J, Owens MR, Rodgers R, Banada P, et al. Rapid detection of mycobacterium tuberculosis and rifampin resistance by use of on-demand, near-patient technology. J Clin Microbiol. 2010;48(1):229–37.

WHO. Automated real-time nucleic acid amplification technology for rapid and simultaneous detection of tuberculosis and rifampicin resistance: Xpert MTB/RIF assay for the diagnosis of pulmonary and extrapulmonary TB in adults and children. Policy update. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2013.

Boehme CC, Nicol MP, Nabeta P, Michael JS, Gotuzzo E, Tahirli R, Gler MT, Blakemore R, Worodria W, Gray C, et al. Feasibility, diagnostic accuracy, and effectiveness of decentralised use of the Xpert MTB/RIF test for diagnosis of tuberculosis and multidrug resistance: a multicentre implementation study. Lancet. 2011;377(9776):1495–505.

Theron G, Zijenah L, Chanda D, Clowes P, Rachow A, Lesosky M, Bara W, Mungofa S, Pai M, Hoelscher M, et al. Feasibility, accuracy, and clinical effect of point-of-care Xpert MTB/RIF testing for tuberculosis in primary-care settings in Africa: a multicentre, randomised, controlled trial. Lancet. 2014;383(9915):424–35.

Hargreaves NJ, Kadzakumanja O, Whitty CJ, Salaniponi FM, Harries AD, Squire SB. Smear-negative' pulmonary tuberculosis in a DOTS programme: poor outcomes in an area of high HIV seroprevalence. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2001;5(9):847–54.

Colebunders R, Bastian I. A review of the diagnosis and treatment of smear-negative pulmonary tuberculosis. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2000;4(2):97–107.

Harries AD, Maher D, Nunn P. An approach to the problems of diagnosing and treating adult smear-negative pulmonary tuberculosis in high-HIV-prevalence settings in sub-Saharan Africa. Bull World Health Organ. 1998;76(6):651–62.

Getahun H, Harrington M, O'Brien R, Nunn P. Diagnosis of smear-negative pulmonary tuberculosis in people with HIV infection or AIDS in resource-constrained settings: informing urgent policy changes. Lancet. 2007;369(9578):2042–9.

Peter JG, Theron G, Van Zyl-smit R, Haripersad A, Mottay L, Kraus S, Binder A, Meldau R, Hardy A, Dheda K. Diagnostic accuracy of a urine lipoarabinomannan strip-test for TB detection in HIV-infected hospitalised patients. Eur Respir J. 2012;40(5):1211–20.

Peter JG, Theron G, Singh N, Singh A, Dheda K. Sputum induction to aid diagnosis of smear-negative or sputum-scarce tuberculosis in adults in HIV-endemic settings. Eur Respir J. 2014;43(1):185–94.

Theron G, Peter J, Meldau R, Khalfey H, Gina P, Matinyena B, Lenders L, Calligaro G, Allwood B, Symons G, et al. Accuracy and impact of Xpert MTB/RIF for the diagnosis of smear-negative or sputum-scarce tuberculosis using bronchoalveolar lavage fluid. Thorax. 2013;68(11):1043–51.

Millen SJ, Uys PW, Hargrove J, van Helden PD, Williams BG. The effect of diagnostic delays on the drop-out rate and the total delay to diagnosis of tuberculosis. PLoS One. 2008;3(4):e1933.

Gupta RK, Lucas SB, Fielding KL, Lawn SD. Prevalence of tuberculosis in post-mortem studies of HIV-infected adults and children in resource-limited settings: a systematic review and meta-analysis. AIDS. 2015;29(15):1987–2002.

Holtz TH, Kabera G, Mthiyane T, Zingoni T, Nadesan S, Ross D, Allen J, Chideya S, Sunpath H, Rustomjee R. Use of a WHO-recommended algorithm to reduce mortality in seriously ill patients with HIV infection and smear-negative pulmonary tuberculosis in South Africa: an observational cohort study. Lancet Infect Dis. 2011;11(7):533–40.

Mukadi YD, Maher D, Harries A. Tuberculosis case fatality rates in high HIV prevalence populations in sub-Saharan Africa. AIDS. 2001;15(2):143–52.

Dheda K, Ruhwald M, Theron G, Peter J, Yam WC. Point-of-care diagnosis of tuberculosis: past, present and future. Respirology. 2013;18(2):217–32.

Dheda K, Davids V, Lenders L, Roberts T, Meldau R, Ling D, Brunet L, van Zyl Smit R, Peter J, Green C, et al. Clinical utility of a commercial LAM-ELISA assay for TB diagnosis in HIV-infected patients using urine and sputum samples. PLoS One. 2010;5(3):e9848.

Minion J, Leung E, Talbot E, Dheda K, Pai M, Menzies D. Diagnosing tuberculosis with urine lipoarabinomannan: systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur Respir J. 2011;38(6):1398–405.

Peter JG, Zijenah LS, Chanda D, Clowes P, Lesosky M, Gina P, Mehta N, Calligaro G, Lombard CJ, Kadzirange G, et al. Effect on mortality of point-of-care, urine-based lipoarabinomannan testing to guide tuberculosis treatment initiation in HIV-positive hospital inpatients: a pragmatic, parallel-group, multicountry, open-label, randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2016.

WHO. The use of lateral flow urine lipoarabinomannan assay (LF-LAM) for the diagnosis and screening of active tuberculosis in people living with HIV: Policy guidance. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2015.

Cohen T, Murray M, Wallengren K, Alvarez GG, Samuel EY, Wilson D. The prevalence and drug sensitivity of tuberculosis among patients dying in hospital in KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa: a postmortem study. PLoS Med. 2010;7(6):e1000296.

Wong EB, Omar T, Setlhako GJ, Osih R, Feldman C, Murdoch DM, Martinson NA, Bangsberg DR, Venter WD. Causes of death on antiretroviral therapy: a post-mortem study from South Africa. PLoS One. 2012;7(10):e47542.

Cox JA, Lukande RL, Lucas S, Nelson AM, Van Marck E, Colebunders R. Autopsy causes of death in HIV-positive individuals in sub-Saharan Africa and correlation with clinical diagnoses. AIDS Rev. 2010;12(4):183–94.

Salaniponi FM, Gausi F, Kwanjana JH, Harries AD. Time between sputum examination and treatment in patients with smear-negative pulmonary tuberculosis. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2000;4(6):581–3.

Banda H, Kang'ombe C, Harries AD, Nyangulu DS, Whitty CJ, Wirima JJ, Salaniponi FM, Maher D, Nunn P. Mortality rates and recurrent rates of tuberculosis in patients with smear-negative pulmonary tuberculosis and tuberculous pleural effusion who have completed treatment. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2000;4(10):968–74.

Harries AD, Nyirenda TE, Banerjee A, Boeree MJ, Salaniponi FM. Treatment outcome of patients with smear-negative and smear-positive pulmonary tuberculosis in the National Tuberculosis Control Programme, Malawi. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 1999;93(4):443–6.

Drain PK, Gounder L, Sahid F, Moosa MY, Rapid Urine LAM. Testing improves diagnosis of expectorated smear-negative pulmonary tuberculosis in an HIV-endemic region. Sci Rep. 2016;6:19992.

Lawn SD, Gupta-Wright A. Detection of lipoarabinomannan (LAM) in urine is indicative of disseminated TB with renal involvement in patients living with HIV and advanced immunodeficiency: evidence and implications. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 2016;110(3):180–5.

WHO. Improving the diagnosis and treatment of smear-negative pulmonary and extrapulmonary tuberculosis among adults and adolescents. Recommendations for HIV-prevalent and resource-constrained settings. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2007.

Katagira W, Walter ND, den Boon S, Kalema N, Ayakaka I, Vittinghoff E, Worodria W, Cattamanchi A, Huang L, Davis JL, Empiric TB. Treatment of severely ill patients with HIV and presumed pulmonary TB improves survival. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2016.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

No funding was received for the research reported.

Availability of data and materials

The dataset used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

NS, AE, and KD were involved in the conception of the study. NS, AE, MB, and KD were involved in study design. NS and MB did the analysis. NS, AE, MB, and KD interpreted the data. NS wrote the first draft. All authors read and approved the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Prior to patient recruitment into the parent study, approval was obtained by the appropriate national regulatory authorities and by the University of Cape Town Human Research Ethics Committee. Informed written consent was obtained for each participant prior to enrollment into the parent study.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

KD has obtained speaker fees at industry-sponsored symposia and non-financial support from Alere in the form of kits and test strips, outside the submitted work. No other authors declare competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Sabur, N.F., Esmail, A., Brar, M.S. et al. Diagnosing tuberculosis in hospitalized HIV-infected individuals who cannot produce sputum: is urine lipoarabinomannan testing the answer?. BMC Infect Dis 17, 803 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12879-017-2914-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12879-017-2914-7