Abstract

Background

Anemia during pregnancy is a public health problem especially in developing countries and it is associated with maternal and perinatal adverse outcomes. There is no meta-analysis on anemia during pregnancy in Sudan. The current systemic review and meta-analysis was conducted to assess the prevalence, types and determinant of anemia during pregnancy in Sudan.

Methods

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guideline was followed. The databases (PubMed, Cochrane Library, Google Scholar, CINAHL, and African Journals Online) were searched using; anemia, pregnancy related anemia and Sudan. Joanna Briggs Institute Meta-Analysis of Statistics Assessment and Review Instrument (JBI-MAStARI) and Modified Newcastle – Ottawa quality assessment scale were used for critical appraisal of studies. The pooled Meta logistic regression was computed using OpenMeta Analyst software.

Results

Sixteen cross-sectional studies included a total of 15, 688 pregnant women were analyzed. The pooled prevalence of anemia among pregnant women in Sudan was 53.0% (95%, CI = 45.9–60.1). The meta-analysis showed no statistical significant between the age (mean difference = 0.143, 95 CI = − 0.033 − 0.319, P = 0.112), parity (mean difference = 0.021, 95% CI = − 0.035 − 0.077, P = 0.465) between the anemic and no anemic women. Malaria was investigated in six studies. Pregnant women who had malaria infection during pregnancy were 1.94 times more likely to develop anemia than women who had no malaria infection (OR = 1.94, 95% CI =1.33–2.82). Six (37.5%) studies investigated type of anemia. The pooled prevalence of iron deficiency anemia (IDA) among pregnant women in Sudan was 13.6% (95% CI = 8.9–18.2).

Conclusion

There is a high prevalence of anemia among pregnant in the different region of Sudan. While age and parity have no association with anemia, malaria infection was associated with anemia. Interventions to promote the strengthening of antenatal care, and access and adherence to nutrition, and malaria preventive measures are needed to reduce the high level of anemia among pregnant women in Sudan.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Anemia during pregnancy is a public health problem especially in developing countries and it is associated with maternal and perinatal adverse outcomes [1]. World Health Organization (WHO) has defined anemia in pregnancy as the hemoglobin concentration of less than 11 g/dl [2]. According to WHO, anemia is considered of a severe public health significance if its rate of ≥40% [3]. Global data shows that 56% of pregnant women in low and middle income countries have anemia [1]. The prevalence of anemia is highest among pregnant women in sub- Sahara Africa (57%), followed by pregnant women in South-East Asia (48%) and lowest prevalence (24.1%) was reported among pregnant women in South America [3].

The causes of anemia during pregnancy in developing countries are multifactorial; these include micronutrient deficiencies of iron, folate and vitamin A and B12, anemia due to parasitic infections such as malaria and hookworm or chronic infections like tuberculosis and HIV [4, 5]. Contributions of each of the factors that cause anemia during pregnancy vary due to geographical location, dietary practice and season. In Sub Saharan Africa inadequate intake of diets rich in iron is reported as the leading cause of anemia among pregnant women [4,5,6].

Anemia during pregnancy is reported to have negative maternal and child health effect and increase the risk of maternal and perinatal mortality [7, 8]. The negative health effects for the mother include fatigue, poor work capacity, impaired immune function, increased risk of cardiac diseases and mortality [1, 8]. Some studies have shown that anemia during pregnancy contributes to 23% of indirect causes of maternal deaths in developing countries [1]. Although, there many published studies on anemia during pregnancy in the different setting of Sudan [9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24], there is no systemic review/ meta-analysis on anemia in Sudan. The current systemic review and meta-analysis was conducted to assess prevalence, types and determinant of anemia during pregnancy in Sudan.

Methods

Study design and search strategy

Findings from published studies were used to conduct this systematic review and meta-analysis to determine the prevalence of anemia, types and its determinants (age, parity and malaria) among pregnant women in Sudan. The major databases of PubMed, Cochrane Library, Google Scholar, CINAHL, and African Journals Online were reviewed for all published studies relevant to anemia during pregnancy and its determinant factors.

All studies that were published up to April 03/2018 were retrieved to be assessed for eligibility of inclusion in this review. In addition, the reference list of each included study was also searched, retrieved and assessed for inclusion eligibility.

The terms that used for searching are: “anemia OR anemia during pregnancy OR determinants of anemia AND Sudan”. Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guideline was followed for conduction of this systematic review and meta-analysis [25].

Study selection and eligibility criteria

Outcome of interest

The primary outcome of this study was the prevalence of anemia during pregnancy. The WHO defines anemia in pregnancy as low blood hemoglobin concentration, below 11 g/dl or hematocrit level less than 33% dl [2]. The secondary outcomes were; types and determinants (age, parity and malaria) of anemia during pregnancy.

Quality assessment and data collection

The included studies were assessed by using Joanna Briggs Institute Meta-Analysis of Statistics Assessment and Review Instrument (JBI-MAStARI) [26]. Modified Newcastle – Ottawa quality assessment scale for cross sectional studies was used to assess the quality of the study for inclusion [27]. The total score for the modified Newcastle – Ottawa scale for cross sectional studies is nine (9) stars as a maximum for the overall scale with the minimum of zero. A study was considered high quality if it achieved 7 out 9 and medium if it achieved 5out of 9, Table 1, Additional file 1.

Two reviewers (IA & YI) independently assessed the quality of each article for inclusion in the review. The disagreement arise between the reviewers was resolved through discussion and involvement of a third reviewer (OE).

A tool for data extraction was developed to extract the most important relevant information for the review. It consists of tables that include information about the authors’ name, year of publication, study location, sample size, age of study participants, and number of pregnancies, malaria with pregnancy, type of anemia and presence and types of complications of anemia.

Data analysis and heterogeneity assessment

OpenMeta Analyst software for Windows [28, 29] was used to perform all the meta-analyses of prevalence and determinants (age, parity and malaria) of anemia. The heterogeneity of the included studies was evaluated using Cochrane Q and the I2. Cochrane Q with P < 0.10 and I2 > 50 was taken as standard to indicate the presence of heterogeneity of the included studies [30]. Based on the results of the analysis of Cochrane Q and I2 the random effects or fixed model was used to combine the included studies accordingly. A sub-group analysis was performed to investigate the association between malaria and anemia.

Results

Study selection

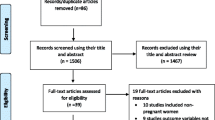

The reviewers found a total of 139 published articles initially. Out of these, 117 were removed due to duplicate records and not fulfilling the criteria. A total of 22 full-text articles were screened for eligibility. Out of these 22, 6 articles were excluded (using varied hemoglobin cut- off, case- control studies and included non-pregnant women. Sixteen studies were included in the final analysis, Fig. 1.

Characteristics of included studies

Sixteen cross-sectional studies were included in this meta-analysis [9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24], Fig. 1. All of the included studies were conducted at health institutions, Additional file 2. All the studies used the WHO definition of anemia during pregnancy which is 11 g/dl [2].

Five (31.2%) of the 16 studies in this review were conducted in Khartoum [15, 17,18,19, 21], six (37.5%) studies were conducted in eastern Sudan (New Half, Kassala and Gadarif) [9, 10, 13, 22,23,24], three studies were conducted in Geizera [12, 14, 16], one study was conducted in Darfur and one study was conducted in Blue Nile [11, 20], Additional file 2.

The minimum sample size was 125 participants in a study conducted in New Halfa [22]. The higher sample size was 8578 conducted in Kassala in Eastern Sudan [24]. Overall, this meta-analysis included a total of 15, 688 pregnant women. The mean (SD) of the age and parity of pregnant women included in this review was 28.5 years and 2.08, respectively, Additional file 2. Six of 16 studies were conducted during delivery/labour (because investigating other outcome e.g. birth outcome), 2 studies were conducted in early pregnancy and the rest in the early third trimester, Additional file 2.

Prevalence of anemia among pregnant women

The minimum prevalence of anemia was 23.46% observed in a study conducted in Khartoum [15]. The highest, 76.0% was observed in a study conducted in Eastern Sudan [9]. The I2 test result showed high heterogeneity (I2 = 98.2%, p < 0.001). Using the random effect analysis, the pooled prevalence of anemia among pregnant women in Sudan was 53.0% (95% CI = 45.9–60.1), Fig. 2.

Association between age, parity and anemia

All the included studies (16) reported the age and parity as continuous variables. Therefore the mean (SD) was compared in this review. The meta-analysis showed no statistical significant between the age (mean difference = 0.143, 95% CI = − 0.033 − 0.319, P = 0.112), parity (mean difference = 0.021, 95% CI = − 0.035 − 0.077, P = 0.465) between the anemic and no anemic women, Figs. 3 and 4. The heterogeneity test showed no statistical evidence of heterogeneity (p = 0.896), therefore the fixed model was used.

Association between malaria infection and anemia

Malaria was investigated (peripheral/ placental) in six studies [9, 10, 13, 20, 22, 23], Additional file 3. Pregnant women who had malaria infection during pregnancy were almost two times more likely to develop anemia during pregnancy than women had no such infection (OR = 1.94 (95% CI = 1.33–2.82). The heterogeneity test showed statistical evidence of heterogeneity, p = < 0.001. Therefore random-effects analysis was used, Fig. 5.

Type of anemia and micronutrient deficiency

Six (37.5%) out of the 16 included studies investigated type of anemia [10, 12, 13, 15, 17, 19]. The minimum prevalence of iron deficiency anemia (IDA) was 6.5% observed in a study conducted in Geizera [12]. The highest prevalence of IDA was 29.3% which was observed in a study Khartoum [17], Additional file 1. The I2 test result showed high heterogeneity (I 2 87.6%, p < 0.001). Using the random effect analysis, the pooled prevalence of IDA among pregnant women in Sudan was 13.6% (95% CI = 8.9–18.2), Fig. 6.

Two studies; in Geizera [12] and in Kassala [13] reported zinc deficiency rate of 45.0% and 38.0%, respectively. Only one study in Gadarif reported 57.7% and 1% of folate and B12 deficiency, respectively [10]. Only one study reported 4.0% copper deficiency in pregnant women in Geizera [12]. C-reactive protein was investigated in one study [13].

Discussion

The main results of this met- analysis is the high prevalence (53.0%) of anemia among pregnant women in the different regions of Sudan. In neighbouring Ethiopia (meta-analysis of twenty studies and a total of 10, 281 pregnant women) the pooled prevalence of anemia among pregnant women in Ethiopia was 31.66% [31]. The prevalence of anemia in this meta-analyses is higher than the rate of anemia among pregnant women in the other African countries e.g. in Uganda 22.1%; [32]. A recent meta-analysis on global rate of anemia reported a lower rate (38%) of anemia in pregnant women, especially among pregnant women in East Africa where the prevalence of anemia was 36% [33]. This high prevalence of anemia in Sudan, is indicative of a severe public health problem, according to the WHO, anemia is considered a severe health problem if prevalence of anemia of ≥40% in a population [3]. It is worth to be mentioned that all the studies included in this meta-analyses were intuitional studies; therefore their results might not reflect the real situation in the community. Recently Kassa et al., have reported that the rate of anemia in pregnancy was much higher in the pooled meta-analyses (31.66%) that the rate (29.0%) of the anemia reported in the national (Ethiopia) survey [31, 34].

The current pooled meta-analyses showed that the age and parity were not different between anemic and non-anemic women. This reflects that anemia affects pregnant Sudanese women regardless to their age or parity. Recent meta-analyses showed that primigravidae were at lower risk for anemia compared with parous women [31]. Likewise, pregnant women with gravidity three to five and six and above were at 1.78, and 2.59 higher risks for anemia [35]. Wessells and colleauges have recently reported that gravidity and malaria were associated with associated with micronutrient deficiency status in pregnant women in Niger [36]. It is belived that women with high parity have low or no iron staorge as it hass been depleted by the repeated pregnaied hence parous women are more likely to be anemic [8]. Generally various risk factors (residence, parity, nutritional) for anemia during have been reported in Ethiopia [35, 37,38,39,40,41]. In Nigeria pregnant women in the rural communities had high pevalence of anemia and iron deficiency anemia compared to pregnant women in the urban setting [42]. In Ugandan Obai et al., have reported that lower prevalence of anemia (22.1%) among pregnant women and housewife were at 1.7 higher risk of anemia [32].

In the current meta-analysis 13.6% of among pregnant women in Sudan had IDA. This rate (13.6%) of IDA was higher than the rate (5%) of IDA reported among rural women of reproductive age in southern Ethiopia [43]. However, 20.7% of pregnant women in Niger had IDA [36].

The pathophysiological mechanism of anemia and its associations with malaria is not yet fully understood. Howver poor inake of food during illness, hemolysis, anemia of inflammation, bone marrow suppression, and micronutrients deficiency are the plasuible explnations for anemia and malaria [44].

Limitiations

Some points need to be mentioned: fisrtly all of these studies were instituational ones. Thus the the findings of these studies might not indicate what is going at the community level. Secondly anemia during pregnancy in Sudan (included in these studies) has been studied mainly in Khartoum, Eastern Sudan and Geizera. There is a pauxity of reports on anemia during pregnancy in the other regions of Sudan e.g.White Nile, North Sudan and Khordofan. Thirdly, types and predictors for anemia during pregnancy were not deeply investiagted in these studies. Some factors such as antenatal care, food security, dietary diversity, maternal education and income need to be taken in the future research. Other types and causes of anemia e.g. folate and vitamin B12 deficiency need to be addressed in more depth.

Conclusion

There is a high prevalence of anemia among pregnant in the different region of Sudan. While age and parity have no association with anemia, malaria infection was associated with anemia. Interventions to promote the strengthening of antenatal care, and access and adherence to nutrition, and malaria preventive measures are needed to reduce the high level of anemia among pregnant women in Sudan.

Abbreviations

- CI:

-

Confidence interval

- IDA:

-

Iron deficiency anemia

- OR:

-

Odd ratio

- WHO:

-

World Health Organization

References

Black RE, Victora CG, Walker SP, Bhutta ZA, Christian P, de Onis M, et al. Maternal and child undernutrition and overweight in low-income and middle-income countries. Lancet. 2013;382:427–51. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(13)60937-X.

World Health Organization. the Global Prevalence of Anaemia in 2011. WHO Rep. 2011;48. doi:https://doi.org/10.1017/S1368980008002401.

Worldwide prevalence of anaemia. 1993. http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/43894/1/9789241596657_eng.pdf. Accessed 21 Feb 2018.

McClure EM, Meshnick SR, Mungai P, Malhotra I, King CL, Goldenberg RL, et al. The association of parasitic infections in pregnancy and maternal and fetal anemia: a cohort study in coastal Kenya. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2014;8:e2724. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pntd.0002724.

Brooker S, Hotez PJ, Bundy DAP. Hookworm-related anaemia among pregnant women: a systematic review. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2008;2:e291. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pntd.0000291.

Ononge S, Campbell O, Mirembe F. Haemoglobin status and predictors of anaemia among pregnant women in Mpigi, Uganda. BMC Res Notes. 2014;7:712. https://doi.org/10.1186/1756-0500-7-712.

Levy A, Fraser D, Katz M, Mazor M, Sheiner E. Maternal anemia during pregnancy is an independent risk factor for low birthweight and preterm delivery. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2005;122:182–6. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejogrb.2005.02.015.

Adam I, AA Ali - Nutritional, 2016 U. Anemia during pregnancy. intechopen.com. https://www.intechopen.com/books/nutritional-deficiency/anemia-during-pregnancy. Accessed 21 Feb 2018.

Adam I, Khamis AH, Elbashir MI. Prevalence and risk factors for anaemia in pregnant women of eastern Sudan. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 2005;99:739–43. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.trstmh.2005.02.008.

Abdelrahim II, Adam GK, Mohmmed AA, Salih MM, Ali NI, Elbashier MI, et al. Anaemia, folate and vitamin B12 deficiency among pregnant women in an area of unstable malaria transmission in eastern Sudan. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 2009;103:493–6. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.trstmh.2008.10.007.

Haggaz AD, Radi EA, Adam I. Anaemia and low birthweight in western Sudan. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 2010;104:234–6. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.trstmh.2009.07.013.

Bushra M, Elhassan EM, Ali NI, Osman E, Bakheit KH, Adam II. Anaemia, zinc and copper deficiencies among pregnant women in Central Sudan. Biol Trace Elem Res. 2010;137:255–61. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12011-009-8586-4.

Mohamed AA, Ali AAA, Ali NI, Abusalama EH, Elbashir MI, Adam I. Zinc, parity, infection, and severe anemia among pregnant women in Kassla, eastern Sudan. Biol Trace Elem Res. 2011;140:284–90. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12011-010-8704-3.

Abdelgadir MA, Khalid AR, Ashmaig AL, Ibrahim ARM, Ahmed A-AM, Adam I. Epidemiology of anaemia among pregnant women in Geizera, Central Sudan. J Obstet Gynaecol. 2012;32:42–4. https://doi.org/10.3109/01443615.2011.617849.

Mubarak N, Gasim GI, Khalafalla KE, Ali NI, Adam I. Helicobacter pylori, anemia, iron deficiency and thrombocytopenia among pregnant women at Khartoum, Sudan. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 2014;108:380–4. https://doi.org/10.1093/trstmh/tru044.

Adam I, Ahmed S, Mahmoud MH, Yassin MI. Comparison of HemoCue® hemoglobin-meter and automated hematology analyzer in measurement of hemoglobin levels in pregnant women at Khartoum hospital, Sudan. Diagn Pathol. 2012;7:30. https://doi.org/10.1186/1746-1596-7-30.

Abdelrahman EG, Gasim GI, Musa IR, Elbashir LM, Adam I. Red blood cell distribution width and iron deficiency anemia among pregnant Sudanese women. Diagn Pathol. 2012;7:168. https://doi.org/10.1186/1746-1596-7-168.

Elmugabil A, Rayis DA, Abdelmageed RE, Adam I, Gasim GI. High level of hemoglobin, white blood cells and obesity among Sudanese women in early pregnancy: a cross-sectional study. Futur Sci OA. 2017;3:FSO182. https://doi.org/10.4155/fsoa-2016-0096.

Abbas W, Adam I, Rayis DA, Hassan NG, Lutfi MF. Higher rate of iron deficiency in obese pregnant sudanese women. Open access Maced J Med Sci. 2017;5:285–9. https://doi.org/10.3889/oamjms.2017.059.

Omer SA, Idress HE, Adam I, Abdelrahim M, Noureldein AN, Abdelrazig AM, et al. Placental malaria and its effect on pregnancy outcomes in Sudanese women from Blue Nile state. Malar J. 2017;16(1):374.

Abdullahi H, Gasim GI, Saeed A, Imam AM, Adam I. Antenatal iron and folic acid supplementation use by pregnant women in Khartoum, Sudan. BMC Res Notes. 2014;7:498. https://doi.org/10.1186/1756-0500-7-498.

Adam I, A-Elbasit IE, Salih I, Elbashir MI. Submicroscopic Plasmodium falciparum infections during pregnancy, in an area of Sudan with a low intensity of malaria transmission. Ann Trop Med Parasitol. 2005;99(4):339-44.

Adam I, Babiker S, Mohmmed AA, Salih MM, Prins MH, Zaki ZM. ABO blood group system and placental malaria in an area of unstable malaria transmission in eastern Sudan. Malar J. 2007;6:110.

Ali AA, Rayis DA, Abdallah TM, Elbashir MI, Adam I. Severe anaemia is associated with a higher risk for preeclampsia and poor perinatal outcomes in Kassala hospital, eastern Sudan. BMC Res Notes. 2011;4:311. https://doi.org/10.1186/1756-0500-4-311.

Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG, PRISMA Group. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. Ann Intern Med. 2009;151:264–9 W64. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/19622511. Accessed 15 Apr 2018.

Munn Z, Moola S, Lisy K, Rittano D. The systematic review of prevalence and incidence data. Joanna Briggs Inst Rev Man 2014 Ed / Suppl. 2014;1–37. http://joannabriggs.org/assets/docs/sumari/ReviewersManual_2014-The-Systematic-Review-of-Prevalence-and-Incidence-Data_v2.pdf. Accessed 15 Apr 2018.

Wells G, Shea B, O’Connell J, Robertson J, Peterson V, Welch V et al. full-text. NewcastleOttawa scale Assess Qual nonrandomised Stud meta-analysis Available http://www.ohrica/programs/clinical_epidemiology/oxfordasp Accessed June 21 2016.

Meta-Analyst O. Open Meta-Analyst - The Tool | Evidence Synthesis in Health. https://www.brown.edu/academics/public-health/research/evidence-synthesis-in-health/open-meta-analyst-tool. Accessed 17 Apr 2018.

Edwards A, Megens A, Peek M, Wallace EM. Sexual origins of placental dysfunction. Lancet (London, England). 2000;355:203–4. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(99)05061-8.

Sedgwick P. Meta-analyses: heterogeneity and subgroup analysis. BMJ (Online). 2013;346:f4040. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.f4040.

Kassa GM, Muche AA, Berhe AK, Fekadu GA. Prevalence and determinants of anemia among pregnant women in Ethiopia; a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Hematol. 2017;17:17. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12878-017-0090-z.

Obai G, Odongo P, Wanyama R. Prevalence of anaemia and associated risk factors among pregnant women attending antenatal care in Gulu and Hoima regional hospitals in Uganda: a cross sectional study. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2016;16:76. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12884-016-0865-4.

Stevens GA, Finucane MM, De-Regil LM, Paciorek CJ, Flaxman SR, Branca F, et al. Global, regional, and national trends in haemoglobin concentration and prevalence of total and severe anaemia in children and pregnant and non-pregnant women for 1995-2011: a systematic analysis of population-representative data. Lancet Glob Heal. 2013;1:e16–25. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2214-109X(13)70001-9.

Ethiopia Demographic and Health Survey. 2016. https://dhsprogram.com/pubs/pdf/FR328/FR328.pdf. Accessed 18 Apr 2018.

Lebso M, Anato A, Loha E. Prevalence of anemia and associated factors among pregnant women in southern Ethiopia: a community based cross-sectional study. PLoS One. 2017;12:e0188783. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0188783.

Wessells K, Ouédraogo C, Young R, Faye M, Brito A, Hess S. Micronutrient status among pregnant women in Zinder, Niger and risk factors associated with deficiency. Nutrients. 2017;9:430. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu9050430.

Mengist HM, Zewdie O, Belew A. Intestinal helminthic infection and anemia among pregnant women attending ante-natal care (ANC) in east Wollega, Oromia, Ethiopia. BMC Res Notes. 2017;10:440. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13104-017-2770-y.

Ebuy Y, Alemayehu M, Mitiku M, Goba GK. Determinants of severe anemia among laboring mothers in Mekelle city public hospitals, Tigray region, Ethiopia. PLoS One. 2017;12:e0186724. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0186724.

Abay A, Yalew HW, Tariku A, Gebeye E. Determinants of prenatal anemia in Ethiopia. Arch Public Health. 2017;75:51. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13690-017-0215-7.

Tadesse SE, Seid O, G/Mariam Y, Fekadu A, Wasihun Y, Endris K, et al. Determinants of anemia among pregnant mothers attending antenatal care in Dessie town health facilities, northern Central Ethiopia, unmatched case -control study. PLoS One. 2017;12:e0173173. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0173173.

Asrie F. Prevalence of anemia and its associated factors among pregnant women receiving antenatal care at Aymiba Health Center, Northwest Ethiopia. J Blood Med. 2017;8:35–40. https://doi.org/10.2147/JBM.S134932.

Okafor IM, Okpokam DC, Antai AB, Usanga EA. Iron status of pregnant women in rural and urban communities of Cross River State, South-South Nigeria. Niger J Physiol Sci. 2017;31:121–5 http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/28262847. Accessed 16 Apr 2018.

Gebreegziabher T, Stoecker BJ. Iron deficiency was not the major cause of anemia in rural women of reproductive age in Sidama zone, southern Ethiopia: a cross-sectional study. PLoS One. 2017;12:e0184742. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0184742.

Gasim G, Deficiency IA-N, 2016 undefined. Malaria, Schistosomiasis, and Related Anemia. intechopen.com. https://www.intechopen.com/books/nutritional-deficiency/malaria-schistosomiasis-and-related-anemia. Accessed 21 Feb 2018.

Acknowledgements

We would like to acknowledge to authors of studies included in this review.

Funding

There are no funding sources for this paper.

Availability of data and materials

The full list of data and the data base entries for all the studies is provided in the paper itself or as additional files.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

IA, YI, and OE designed the study and participated in the manuscript drafting. IA, and YI conducted data extraction and statistical analyses. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Additional files

Additional file 1:

Assessment of publication bias. (XLSX 13 kb)

Additional file 2:

Characteristics of all studies included in the systematic review and meta-analysis. (XLSX 13 kb)

Additional file 3:

Characteristics of the studies investigated malaria and anemia. (XLSX 10 kb)

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Adam, I., Ibrahim, Y. & Elhardello, O. Prevalence, types and determinants of anemia among pregnant women in Sudan: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Hematol 18, 31 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12878-018-0124-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12878-018-0124-1