Abstract

Background

Care pathways (CPWs) are complex interventions that have the potential to reduce treatment errors and optimize patient outcomes by translating evidence into local practice. To design an optimal implementation strategy, potential barriers to and facilitators of implementation must be considered.

The objective of this systematic review is to identify barriers to and facilitators of the implementation of CPWs in primary care (PC).

Methods

A systematic search via Cochrane Library, CINAHL, and MEDLINE via PubMed supplemented by hand searches and citation tracing was carried out. We considered articles reporting on CPWs targeting patients at least 65 years of age in outpatient settings that were written in the English or German language and were published between 2007 and 2019. We considered (non-)randomized controlled trials, controlled before-after studies, interrupted time series studies (main project reports) as well as associated process evaluation reports of either methodology. Two independent researchers performed the study selection; the data extraction and critical appraisal were duplicated until the point of perfect agreement between the two reviewers. Due to the heterogeneity of the included studies, a narrative synthesis was performed.

Results

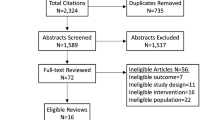

Fourteen studies (seven main project reports and seven process evaluation reports) of the identified 8154 records in the search update were included in the synthesis. The structure and content of the interventions as well as the quality of evidence of the studies varied.

The identified barriers and facilitators were classified using the Context and Implementation of Complex Interventions framework. The identified barriers were inadequate staffing, insufficient education, lack of financial compensation, low motivation and lack of time. Adequate skills and knowledge through training activities for health professionals, good multi-disciplinary communication and individual tailored interventions were identified as facilitators.

Conclusions

In the implementation of CPWs in PC, a multitude of barriers and facilitators must be considered, and most of them can be modified through the careful design of intervention and implementation strategies. Furthermore, process evaluations must become a standard component of implementing CPWs to enable other projects to build upon previous experience.

Trial registration

PROSPERO 2018 CRD42018087689.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

A care pathway or clinical pathway (CPW) is an evidence-based structured multi-disciplinary care plan that describes all relevant diagnostic and therapeutic steps in the care of patients with a specific health problem in chronological order. A CPW is used to translate evidence into local practice by considering regional conditions and demands [1, 2] as the final step of implementing evidence-based knowledge into practice. Due to the standardization of care, a CPW has the potential to reduce treatment errors, impact patient outcomes and quality of care and increase the effectiveness of health care systems [1, 3]. CPWs have been implemented in international practice since the 1980s [4] and are increasingly being used worldwide, especially in inpatient care in Australia, the USA, Canada, Europe and Asia [5], for example, with the HEART Pathway [6], the Liverpool CPW for patients with cancer [7] or CPWs for total knee arthroplasty in surgery [8]. Due to the epidemiological and demographic changes in the Western world, primary health care systems must change, and it is important to align quality of care and evidence-based practice with economic aspects and patients’ expectations. CPWs might be an answer to addressing unwanted variation in primary care (PC) that hampers reliable, patient-centred evidence-based care [9, 10]. However, there is still low utilization of CPWs in PC, even though general practitioners (GPs) see them as highly relevant [11]. Based on the important influence of contextual factors on the effectiveness of complex interventions [12] there is a low transferability of CPWs across different countries and settings when not understood adequately and reported in and adequate manner. The same applies to implementation strategies which have to be tailored and adapted to the different demands and contexts, e.g. of outpatient and inpatient care settings [2].

To develop successful implementation strategies for CPWs in PC, information about potential barriers and facilitators should be taken into account. Thus, our review addresses the following review question: Which barriers and facilitators to implementing multi-disciplinary CPWs for people aged ≥65 years in PC have been reported in the literature?

Since aged people often suffer from multimorbidity and therefore have special demands, we decided to focus on this particularly vulnerable group in PC. Vertigo, dizziness and balance disorders as frequent complaints of older people [13,14,15,16], for example, are a common reasons for their consultation in general practice [17]. Due to multifactorial etiology [18,19,20,21], the overutilization of health care in affected patients insufficiently treated in PC has been shown [22, 23].

Methods

Search strategy

A systematic search of literature was carried out in three electronic databases, Cochrane Library, CINAHL, and MEDLINE via PubMed. Additional sources were identified via hand searches, citation tracing and internet searches for grey literature. The initial search took place in December 19th, 2017, and a search update was conducted in July 15th, 2019. The search strategy was based on the Medline search strategy used for a Cochrane review titled Clinical pathways for primary care: effects on professional practice, patient outcomes, and costs [2], which is currently available as protocol.

An overview of all search strategies used, terms, filters and number of results can be accessed in Additional file 1.

The review protocol was registered at PROSPERO 2018 CRD42018087689 and is available from https://www.crd.york.ac.uk/prospero/display_record.php?%20ID=CRD42018087689.

Reporting of this systematic review followed the PRISMA checklist [24].

Selection criteria

To identify publications with relevant interventions, we used criteria as the intervention must be a structured and stepwise detailed multi-disciplinary plan that must be applied to translate evidence into practice in the local context and aims the standardization of care for a specific health problem in a specific group of patients [2]. We did not include screening, detection, risk prediction or primary preventive CPWs or pharmacological guidelines. This also refers to CPWs that deal exclusively with diagnostics and are not an intervention according to our underlying definition [2]. The target population was people aged ≥65 years in PC setting, which was defined as “[ …] products or services designed to address acute and episodic health conditions and to manage chronic health conditions. It is also [ …] where patients receive first contact care and where those in need of more specialized services are connected with other parts of the healthcare system.” [25]. Thus, we considered providers as all health professionals (HPs), including doctors as GPs and medical specialists, nurses, physical therapists, pharmacists, occupational therapists, social workers, dietitians, psychologists, and dentists involved in CPW utilization in PC setting. As patients sometimes inappropriate tend to go to the emergency rather than to their GP for reasons as intricate appointment systems and appointment availability in general practice [26], hospital stays less than 24 h were also included.

For more detail of selection criteria based on PICO construct, see Table 1.

Study designs considered for inclusion

We included randomized controlled trials (RCTs), non-randomized controlled trials (NRCTs), controlled before-after studies (CBAs) and interrupted time series (ITS) studies, according to the Effective Practice and Organisation of Care (EPOC) study design criteria [27], written in German or English language and published from 2007 to 2019, whereby preliminary results or pilot/feasibility studies were excluded. For further detail, see Table 1.

In general, we did not exclude studies with a high risk of bias (RoB), indicating lower quality, but we did consider the RoB in the rating.

The titles, abstracts and subsequent full texts of the identified studies were screened and assessed for eligibility independently by two researchers (ES, VR). Disagreement between them was resolved through discussion, and a third reviewer (MM) was consulted if necessary. The study selection process, including deduplication, was documented, made consistent between the researchers and managed by using the Cochrane technology platform Covidence.

Since we assumed that it is possible, that barriers to and facilitators of implementation are not reported within the main publication of the respective project (main project report) but in independent publications, we carried out citation tracing of eligible articles to identify and include associated process evaluation reports.

Data extraction and analysis

After the exclusion of non-eligible articles through the removal of obviously irrelevant reports based on the title and abstract screening and through the examination of the retrieved full texts of the potentially relevant reports, the remaining studies were extracted by using a previously piloted template based on the EPOC good practice data extraction form [28] supplemented by items from the data extraction tool of the Context and Implementation of Complex Interventions (CICI) framework [12]. If there were more relevant articles published for one original project, the various related records were extracted in one form. Data extraction forms are available from the authors on request.

The data collection process was performed by two independent researchers: ES extracted the data from all studies, and this process was duplicated by VR until the point of perfect agreement between the two reviewers. Discrepancies in the comparison of the forms were resolved by discussion and consensus.

Due to the large diversity of study characteristics and heterogeneous interventions and outcomes, a meta-analysis was not possible. Thus, a narrative synthesis following the guidance for undertaking reviews in health care from the Centre for Reviews and Dissemination (CRD) [29], as well as a synthesis in tabular form (see Tables 2 and 3) was undertaken.

Critical appraisal

The critical appraisal was carried out by two independent researchers (the critical appraisal was conducted in its entirety by ES and then duplicated by VR until the point of perfect agreement between the two reviewers), and a third reviewer (MM) was involved if necessary.

We used the Cochrane Collaboration’s tool for assessing RoB for (N)RCTs and CBAs by completing the RoB table via Review Manager (RevMan) 5.3 software [44]; in cluster randomized trials, we also considered the risk of particular bias as recommended by the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions [45]; in ITS we used the seven standard criteria [46]. We judged each domain as being at low, high, or unclear risk (Additional file 2) and created a RoB summary figure (see Additional file 3) and a graph to illustrate the proportion of studies with each of the judgements (see Fig. 2).

For the process evaluation reports, we used the Critical Appraisal Skills Programme (CASP) Checklist for qualitative research [47] and the Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool (MMAT) [48]. An overview of critical appraisal tools used for the included study designs is given in Additional file 4.

Results

Study selection

The search generated 8154 hits. After removing duplicates and irrelevant publications based on the title and abstract screening, we assessed 367 full-text articles for eligibility, six of which originated from the additional hand and citation searching. After the exclusion of 353 articles (see Fig. 1 for the PRISMA flow chart), a total of 14 studies (seven main project reports and seven process evaluation reports) were included in the synthesis.

The presentation of the results is based on the different included CPWs of the seven main project reports.

Characteristics of included studies

One main project report was a RCT [30] and six were cluster RCTs (cRCTs) [32, 36, 37, 39, 41, 42]. Two included nested process evaluation components in the main report [36, 41] and for five additional process evaluation reports were published separately. Details on the characteristics and results of the included studies can be found in Table 2.

The studies were published between 2008 and 2017 and took place in PC settings in three different countries: five in the Netherlands [32, 37, 39, 41, 42], one in the UK [36] and one in Canada [30].

The included projects comprised 5822 participants (3634 patients in intervention groups; 2188 patients in control groups).

The mean ages in the intervention groups ranged from 67.1 to 81.7 years and from 66.0 to 82.8 years in the control groups. One study only reported overall age range and did not report mean age [36].

All projects compared CPWs with usual care to assess their effectiveness. Three projects tested a CPW for persons with specific health conditions, which were type 2 diabetes [41], chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) [42], and heart failure [30]. The other projects targeted on community-dwelling people [32, 36, 37, 39]. More detailed information about the study characteristics and the results of single studies can be found in Table 2.

Despite the general diversity of the seven CPWs, there were commonalities with regard to the development and structure of the interventions. Thus, e.g. the development of all interventions was evidence-based, and four studies reported the involvement of clinicians. A total of six CPWs provided an individually tailored treatment. Education and training for health care providers was included in six CPWs. More detailed information about the structure of the interventions is displayed in Additional file 5. No project provided a clear and comprehensive distinction between intervention components and used implementation strategy. For details of the components of the seven CPWs, see Table 2.

Detailed information about characteristics of excluded studies and reasons for exclusion are available from the authors upon reasonable request.

Outcome measures

Five projects used patient-relevant primary outcomes, such as disability [39], daily functioning [32], functional performance in activities of daily living and mental well-being [37], quality of life and functional capacity for older females living with heart failure [30] and health status of COPD patients [42]. Two studies investigated surrogate endpoints, such as changes in average daily step count [36] and the percentage of people with poor glycaemic control [41].

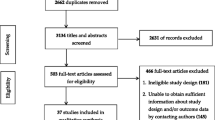

Quality of evidence

Details of the judgements about each RoB item in the included (cluster-)randomized controlled studies and across these trials are shown in Additional file 2, Additional file 3 and Fig. 2.

Risk of bias graph of RCTs and cRCTs (designed by using RevMan [44])

Due to a lack of information in almost all studies, the authors judged a total of 43,6% (n = 24/55) of RoB domains as being unclear (38,2% as low risk: n = 21/55; 18,2% as high risk: n = 10/55). For a detailed information on RoB assessment see Fig. 2 and Additional file 3.

The problem of poor reporting was also relevant in the quality assessment of the process evaluation reports (see Additional file 6 for CASP and Additional file 7 for MMAT). None of the studies that use qualitative methods adequately described the relationship and interaction between the participants and the researcher. This also applies to qualitative parts of mixed-methods studies. One qualitative study did not report approval of an ethics committee or institutional review board.

Factors influencing the success of implementation

The classification of barriers to and facilitators of successful implementation of CPWs in PC was based on the context, implementation and setting dimensions of the CICI framework [12].

An overview of barriers and facilitators in the individual studies is shown Table 3. Barriers were most frequently identified within the dimensions of implementation agents (n = 7) and setting (n = 4). Facilitators were most frequently determined within the implementation agents (n = 6) and implementation strategies (n = 4) (see Table 4).

Context

Three CPWs considered aspects of the epidemiological context such as multi-morbid [31, 33, 43] patients aged at least 85 years [33] with mental health problems [35] as barriers to applying an intervention.

Two of the CPWs reported the cultural background [33, 43], a low health literacy [43] and gender [33, 43] as potential barriers that could be attributed to the domain of socio-cultural context. Such patient-related characteristics can lead to a time lag in the application of an intervention. Additionally, the frequency of general practice visits [33, 43] have been reported to have a negative impact by two CPWs and could therefore be seen as barrier according to two CPWs.

Additionally, two CPWs considered a low socio-economic status [33, 43] within the domain of socio-economic context as barriers to applying an intervention.

Furthermore, aspects related to the political context, such as a lack of an incentive systems [41] or adequate reimbursement models [43] or absent monetary compensations [33], were reported in three CPWs as potential barriers for the effective implementation of an intervention.

No barriers or facilitators within the domains geographical, ethical and legal context could be identified. None of the CPWs described facilitators in any of the dimensions of the domain context.

Implementation

Within the domain of implementation strategies the involved HPs of three CPWs emphasized the importance of training activities and reported appropriate training and education in applying an intervention [33, 36, 41] as facilitator. One CPW considered an overload of information during training activities as potential barrier [40]. According to the results of one CPW, a handbook as facilitator can serve as a clear guideline for HPs to promote a structured application of intervention [43].

The domain of implementation agents can be divided into the two areas of HPs and patients.

On the one hand, HPs’ insufficient or even lack of knowledge about how to perform intervention components such as assessments or tests [33, 40, 41], their lack of competence in general [40] and their insufficient experience and job training [40] were considered barriers regarding knowledge and skills in three CPWs. On the other hand, three CPWs identified knowledge and skills such as professional [33, 40, 43], organizational [33] and communication skills [33] and empathic capacity [33] as serving as facilitators to the implementation of the approach. The behaviour-related factors of attitude and awareness, such as a lack of motivation of end-users [41] (n = 1) and initial difficulties in implementation due to changes in routines [40, 43] (n = 2) were reported as barrieres, which can reduce the success of intervention. Further barriers were negative attitude towards the intervention, such as doubts about the expected results [33] in one CPWs, and reluctance regarding an intervention component due to a lack of agreement [41, 43] in two included CPWs, e.g., the prescription of multiple drug regimes [41]. In contrast, a positive attitude towards the effectiveness of the intervention [33, 43] is reported to be a facilitator according to two CPWs. One CPW stated that interventions that provide recommendations to both patients and GPs increased adherence among HPs and affected patients and are therefore facilitators [38].

Interaction-related factors were identified in five CPWs as influencing aspects. In this regard, HPs named communication and collaboration issues [33] and difficulties in organizing team meetings [40] as barriers. HPs considered good interdisciplinary communication and cooperation [33, 35, 40] in two included CPWs as well as clear roles and task definition [33, 40] in two CPWs as facilitators. In addition to the consideration of the multi-disciplinary team, the positive impact of intradisciplinary communication and cooperation was identified in two included CPWs as a facilitator [33, 41], e.g., by making comparisons with peers [41]. The integration of family caregivers into the intervention, if possible, was identified as facilitator in one CPW [34], whereas insufficient involvement of single professions was mentioned as barrier in one CPW [33]. According to three CPWs, further barriers in application of the CPW arise due to the extent of intervention, such as time-consuming parts [33, 40, 43] and overly complex intervention components [33, 40]. Two CPWs reported an individual, flexible, tailored intervention customized to patients’ needs, wishes and preferences providing the HPs as major facilitator in application [33, 43]. Another facilitator in implementation is a good fit of the intervention to the day-to-day work of the delivery agents [43]. A practicable layout of the intervention can ease adoption in daily practice [43] as facilitator sccording to one included CPW.

In addition to HPs, patients as consumers of the intervention, were also considered to affect implementation success. Aspects in this domain were partly identified by the patients themselves (self-assessments) and partly by HPs based on their experiences with affected patients (external assessments): regarding behaviour-related factors, HPs in three CPWs assumed patients’ motivational issues to be a reason for their low treatment adherence and therefore as barrier [33, 38, 43]. Furthermore, external factors such as transportation issues, sometimes due to adverse weather conditions or scheduling conflicts with other appointments, affected the adherence of intervention recipients and serve as barriers [31]. Similar to HPs, patients in two studies also indicated that positive expectations regarding interventions [33, 40] were a facilitator. The delivery was also affected by the structure of the intervention components. Participants of one CPW perceived high temporal expenditure due to time-consuming participation to be a barrier [40]. Recipients of each one CPW classified high bureaucratic effort [36] and difficulties in distinguishing the involved disciplines [40] as barriers. On the other hand, two CPWs reported tailored interventions meeting patients’ current needs [33, 34, 36]; one CPW the possibility for adaptations to avoid excessively restricting their own decision making, e.g., through self-management approaches [40]; and one CPW close monitoring of changing situations, which transmits a sense of security [34], as facilitators. Furthermore, in one CPW the provision of written advice such as a handbook [36] and the use of technical devices for outcome measurement [36] were seen as facilitators by consumers. In addition, patients considered interactions with HPs through personal meetings [36, 40] in two CPWs, good professional-patient relationships [33, 34, 40] in two CPWs and good internal exchange between HPs [34] in one CPW to be facilitators.

Within the domain of implementation outcomes two CPWs reported a barrier in problems occurred during the identification of the appropriate target group as the first step of the intervention [33, 40], e.g., due to dysfunctional screening methods [40].

No barriers or facilitators within the domains implementation theory and implementation process were reported. In addition, no facilitators within the domain of implementation outcomes were mentioned by included CPWs.

Setting

Barriers reported in four CPWs within the work environment in the dimension of setting are inadequate staffing due to the general lack of available staff [31, 33], e.g., due to illness or part-time employment [31] and lack of sufficiently educated staff [33]. Structural conditions lead to time pressure [33, 35, 41, 43], e.g., due to excessive workload in daily practice [35, 43], which negatively affects the situational performance of intervention components. Additionally, two CPWs mentioned a lack of space as barrier [31, 43]. Also, one CPW cited discontinuity problems in GPs as a barrier [34]. Transparency about referral possibilities promoting the familiarity of HPs with these options was identified as a facilitator [33].

Discussion

This study analysed barriers to and facilitators of the implementation of CPWs in PC to gain a better understanding of the factors needed for their successful implementation.

We found that the implementation of interventions into practice requires changes and adaptations in the knowledge, attitudes and behaviour of HPs to achieve a positive impact on outcomes. The finding on the negative influence of personal factors of HPs, such as their lack of knowledge and their attitudes, is in line with findings from a review about barriers and strategies in guideline implementation [49] and a review of staff-reported barriers and facilitators to implementation of hospital-based, patient-focused interventions [50]. Our results show that appropriate training activities for HPs are particularly relevant, as confirmed by a larger feasibility study evaluating a local coronary heart disease treatment pathway in PC [51]. Two systematic reviews focusing on in-hospital settings showed similar results [49, 50]. We found that HPs considered the use of a structured, step-by-step explanatory handbook as a facilitator [43]. This finding is in line with the results of a feasibility study in PC [37]. Findings from another feasibility study suggested that additional material such as small portable cards with inclusion criteria, telephone numbers and listed referral options are helpful [52]. A meta-analysis of the effectiveness of implementation strategies for non-communicable disease guidelines in primary health care concluded that the simple provision of educational materials without training is ineffective [53]. In line with our findings, a review on secondary care found that providing information about successful examples can lower implementation barriers and enhance adherence [50]. Regarding the results showing that HPs have difficulties accepting interventions due to negative attitudes or reluctance regarding intervention components, similar studies also stated that it seems to be advisable to integrate local end-users into the development and implementation process [49, 51], which is in line with the UK Medical Research Council (MRC) guidance that recommends involving local end-users to promote successful long-term establishment of effective intervention in practice [54].

Our results show that intervention success also depends on patients’ acceptance and adherence, e.g., due to the risk of a lack of understanding of recommendations. The identified facilitators such as precise and thoroughly explained recommendations [38] as well as the provision of written advice for patients [36] seem to be easy to use in practice. Reasons for negative attitudes towards interventions must be analysed individually to find solutions to promote acceptance and adherence. We also found that the application of an intervention can be made more difficult and time consuming due to several unavoidable patient-related factors, such as age [33], multi-morbidity [31, 33, 43] and cultural background [33, 43]. To counteract this difficulty, CPWs should be designed to be truly contextualised to the local settings, as well as taking into consideration common issues faced by the elderly age group.

We identified a good fit of the intervention with the day-to-day work of the delivery agents as a facilitator [43]. To promote a good fit, other studies suggested the integration of interventions into practice software in PC [51] or the use of tablets or smartphones in in-hospital settings [49]. Metzelthin et al. [40], in relation to a process evaluation of the implementation of a nurse-led care approach for community-dwelling frail older people, observed that digitalization of forms may additionally favour interdisciplinary exchange of data. Our results showed that clearly defined responsibilities with regard to tasks and roles are the basic prerequisite for multi-disciplinary communication and cooperation to promote efficient healthcare delivery [33, 40], which is in line with findings for in-hospital settings [49]. These findings underline the importance of the careful CPWs design in order to build upon current practice and take into account day-to-day practice to ensure the uptake by HPs. Since we identified a lack of time [33, 35, 41, 43] as well as overly time-consuming [33, 40, 43] and complex [33, 40] intervention components as barriers, the CPW application should not be associated with too much effort, especially since HPs are already under time pressure. Recommendations and tools have to be plausible, clear and transparent and be presented in a user-friendly, simplified and short form, consistent with findings for in-hospital settings [49, 50]. Furthermore, they must be evidence-based, which is in line with findings in PC [51] as well as with secondary care setting [49]. Thus, Kramer et al. [51] stated that recommendations must conform to the advice of guidelines or other (inter)national guidance to avoid contradictory or overlapping recommendations, whereas an integration into a larger geographic context may facilitate implementation.

A lack of financial incentives and compensation [33, 41, 43] were reported to be important barriers. To overcome this issue, projects should plan to use case payments, and new reimbursement options should be considered to facilitate long-term implementation.

Notably, the retrieved studies originated from a few different studies, and most of them were conducted in the Netherlands [32, 37, 39, 41, 42].

Limitations

This systematic review has some limitations. An important issue is the evaluation of the main inclusion criterion. The terms care pathways and critical pathways were not consistently used in the literature. We tried to overcome this issue by applying a broad definition of CPWs [2] to allow for consistency among the compared studies. Eventhough both the European Pathway Association (E-P-A) in 2007 [55] and a Cochrane review from 2010 [3] indicated that CPWs have to be considered as a complex intervention, it seems not to be common sense [54] that therefore, CPWs have to be developed and evaluated in a specific manner. This might explain the lack of systematic and rigorous investigation of the context, in terms of barriers and facilitators that would allow thorough evaluation of the external validity of the implemented CPWs.

Transferability of review results

Despite the general interest of GPs in CPWs, there is a low utilization of CPWs in PC [11]. Therefore, the included studies in this systematic review were conducted in the UK, Canada, and the Netherlands. This limits the transferability of our findings to similar healthcare contexts. It is obvious that the transferability of our findings might be limited to similar healthcare contexts with a strong gate-keeper role of the GP in PC, and the publicly funded healthcare systems in the UK and Canada [56]. The Dutch healthcare system is based on a different funding model, but with the same gatekeeper role of GPs to refer patients to specialists which are based at hospitals.

The varying funding mechanisms in the different countries were the primary studies were conducted may represent another limitation. The publicly funded (tax-based) healthcare systems in the UK and Canada differ significantly from the Dutch system. The Dutch system is funded by a dual system that came into effect in January 2006 [56]. It consists of a publicly funded component, and via a basic healthcare insurance package which is mandatory. Every Dutch resident has to choose their basic insurance package in order to define the scope of the healthcare services provided [56]. This means that the transferability of our systematic review findings are limited to countries with a similar healthcare system. Moreover, the financial incentives offered in the Dutch healthcare system could be confounding mechanisms or facilitators of successful implementation itself, and not the CPW as a causal factor [56].

In addition, the poor quality of reporting in terms of missing information for many core items made a straightforward assessment of internal validity difficult and might have led to inappropriate downgrading. We are, however, confident that our rigorously applied approach and reporting of all steps makes the conclusions transparent.

Conclusions

In the implementation of CPWs in PC practice, a multitude of barriers and facilitators must be considered, and most of them can be modified through careful design of intervention and implementation strategies. We observed a lack of transparent and comprehensive reporting of the intervention components, their implementation strategies and contexts. There is an urgent need to improve the quality of research on CPWs and to follow the established guidelines in conducting and reporting research involving comprehensive process evaluations to produce reliable and transferable evidence to make this promising technology available for practice.

Availability of data and materials

Data extraction forms are available from the authors on request.

Abbreviations

- CASP:

-

Critical Appraisal Skills Programme

- CBA:

-

Controlled before-after study

- CG:

-

Control group

- CICI:

-

Context and Implementation of Complex Interventions

- COPD:

-

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease

- CPW:

-

Care pathway

- cRCT:

-

Cluster randomized controlled trial

- CRD:

-

Centre for Reviews and Dissemination

- E-P-A:

-

European Pathway Association

- EPOC:

-

Effective Practice and Organisation of Care

- GP:

-

General practitioner

- HP:

-

Health professional

- IG:

-

Intervention group

- ITS:

-

Interrupted time series

- MMAT:

-

Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool

- MRC:

-

Medical Research Council

- NRCT:

-

Non-randomized controlled trial

- PC:

-

Primary care

- PICO:

-

Population, Intervention, Comparison(s) and Outcome

- RCT:

-

Randomized controlled trial

- RoB:

-

Risk of bias

References

Lawal AK, Rotter T, Kinsman L, Machotta A, Ronellenfitsch U, Scott SD, et al. What is a clinical pathway? Refinement of an operational definition to identify clinical pathway studies for a Cochrane systematic review. BMC Med. 2016;14:35.

Rotter T, Kinsman L, Machotta A, Zhao FL, van der Weijden T, Ronellenfitsch U, et al. Clinical pathways for primary care: effects on professional practice, patient outcomes, and costs. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013;85:37.

Rotter T, Kinsman L, James E, Machotta A, Gothe H, Willis J, et al. Clinical pathways: effects on professional practice, patient outcomes, length of stay and hospital costs. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2010:CD006632.

Kinsman L, Rotter T, James E, Snow P, Willis J. What is a clinical pathway? Development of a definition to inform the debate. BMC Med. 2010;8:31.

Vanhaecht K, Bollmann M, Bower K, Gallagher C, Gardini A, Guezo J, et al. Prevalence and use of clinical pathways in 23 countries – an international survey by the European pathway association. J Integr Care Pathways. 2006;10:28–34.

Gesell SB, Golden SL, Limkakeng AT Jr, Carr CM, Matuskowitz A, Smith LM, et al. Implementation of the HEART pathway: using the consolidated framework for implementation research. Crit Pathw Cardiol. 2018;17:191–200.

Costantini M, Romoli V, Leo SD, Beccaro M, Bono L, Pilastri P, et al. Liverpool care pathway for patients with cancer in hospital: a cluster randomised trial. Lancet (London, England). 2014;383:226–37.

Loftus T, Agee C, Jaffe R, Tao J, Jacofsky DJ. A simplified pathway for total knee arthroplasty improves outcomes. J Knee Surg. 2014;27:221–8.

Grol R. Successes and failures in the implementation of evidence-based guidelines for clinical practice. Med Care. 2001;39:Ii46–54.

McGlynn EA, Asch SM, Adams J, Keesey J, Hicks J, DeCristofaro A, et al. The quality of health care delivered to adults in the United States. N Engl J Med. 2003;348:2635–45.

Toy JM, Drechsler A, Waters RC. Clinical pathways for primary care: current use, interest and perceived usability. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2018;25:901–6.

Pfadenhauer LM, Gerhardus A, Mozygemba K, Lysdahl KB, Booth A, Hofmann B, et al. Making sense of complexity in context and implementation: the context and implementation of complex interventions (CICI) framework. Implement Sci. 2017;12:21.

Neuhauser HK, Radtke A, von Brevern M, Lezius F, Feldmann M, Lempert T. Burden of dizziness and vertigo in the community. Arch Intern Med. 2008;168(19):2118–24.

Agrawal Y, Carey JP, Della Santina CC, Schubert MC, Minor LB. Disorders of balance and vestibular function in US adults: data from the National Health and nutrition examination survey, 2001-2004. Arch Intern Med. 2009;169(10):938–44.

Verghese J, Ambrose AF, Lipton RB, Wang C. Neurological gait abnormalities and risk of falls in older adults. J Neurol. 2010;257(3):392–8.

Lin HW, Bhattacharyya N. Balance disorders in the elderly: epidemiology and functional impact. Laryngoscope. 2012;122(8):1858–61.

Bösner S, Schwarm S, Grevenrath P, Schmidt L, Hörner K, Beidatsch D, et al. Prevalence, aetiologies and prognosis of the symptom dizziness in primary care - a systematic review. BMC Fam Pract. 2018;19(1):33.

Gomez F, Curcio CL, Duque G. Dizziness as a geriatric condition among rural community-dwelling older adults. J Nutr Health Aging. 2011;15(6):490–7.

Maarsingh OR, Dros J, Schellevis FG, van Weert HC, van der Windt DA, ter Riet G, et al. Causes of persistent dizziness in elderly patients in primary care. Ann Fam Med. 2010;8(3):196–205.

Radtke A, Lempert T, von Brevern M, Feldmann M, Lezius F, Neuhauser H. Prevalence and complications of orthostatic dizziness in the general population. Clin Auton Res. 2011;21(3):161–8.

Jahn K, Kressig RW, Bridenbaugh SA, Brandt T, Schniepp R. Dizziness and unstable gait in old age: etiolog, Diagnosis and Treatmenty. Dtsch Arztebl Int. 2015;112(23):387–93.

Grill E, Strupp M, Müller M, Jahn K. Health services utilization of patients with vertigo in primary care: a retrospective cohort study. J Neurol. 2014;261(8):1492–8.

Grill E, Penger M, Kentala E. Health care utilization, prognosis and outcomes of vestibular disease in primary care settings: systematic review. J Neurol. 2016;263:36–44.

Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS Med. 2009;6:e1000097.

Watson DE, Broemeling A, Wong S. A Results-Based Logic Model for Primary Healthcare: A Conceptual Foundation for Population-Based Information Systems. Healthc Pol. 2009;5:33–46 (Spec No).

MacKichan F, Brangan E, Wye L, Checkland K, Lasserson D, Huntley A, et al. Why do patients seek primary medical care in emergency departments? An ethnographic exploration of access to general practice. BMJ Open. 2017;7(4):e013816.

Cochrane Effective Practice and Organisation of Care (EPOC), editor. What study designs can be considered for inclusion in an EPOC review and what should they be called? EPOC Resources for review authors, 2017. epoc.cochrane.org/resources/epoc-resources-review-authors. Accessed 10 Feb 2018.

Cochrane Effective Practice and Organisation of Care (EPOC), editor. Data collection form. EPOC Resources for review authors, 2013. http://epoc.cochrane.org/epoc-specific-resources-review-authors. Accessed 10 Feb 2018.

Centre for Reviews and Dissemination (CRD). Systematic reviews: CRD's guidance for undertaking reviews in health care. York, GB: Centre for Reviews and Dissemination, University of York; 2009.

Azad N, Molnar F, Byszewski A. Lessons learned from a multidisciplinary heart failure clinic for older women: a randomised controlled trial. Age Ageing. 2008;37:282–7.

Byszewski A, Azad N, Molnar FJ, Amos S. Clinical pathways: adherence issues in complex older female patients with heart failure (HF). Arch Gerontol Geriatr. 2010;50:165–70.

Bleijenberg N, Drubbel I, Schuurmans MJ, Dam HT, Zuithoff NP, Numans ME, et al. Effectiveness of a proactive primary care program on preserving daily functioning of older people: a cluster randomized controlled trial. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2016;64:1779–88.

Bleijenberg N, Ten Dam VH, Steunenberg B, Drubbel I, Numans ME, De Wit NJ, et al. Exploring the expectations, needs and experiences of general practitioners and nurses towards a proactive and structured care programme for frail older patients: a mixed-methods study. J Adv Nurs. 2013;69:2262–73.

Bleijenberg N, Boeije HR, Onderwater AT, Schuurmans MJ. Frail older adults' experiences with a proactive, nurse-led primary care program: a qualitative study. J Gerontol Nurs. 2015;41:20–9 quiz 30-1.

Bleijenberg N, Ten Dam VH, Drubbel I, Numans ME, de Wit NJ, Schuurmans MJ. Treatment fidelity of an evidence-based nurse-led intervention in a proactive primary care program for older people. Worldviews Evid-Based Nurs. 2016;13:75–84.

Harris T, Kerry SM, Victor CR, Ekelund U, Woodcock A, Iliffe S, et al. A primary care nurse-delivered walking intervention in older adults: PACE (pedometer accelerometer consultation evaluation)-lift cluster randomised controlled trial. PLoS Med. 2015;12:e1001783.

Melis RJ, van Eijken MI, Teerenstra S, van Achterberg T, Parker SG, Borm GF, et al. A randomized study of a multidisciplinary program to intervene on geriatric syndromes in vulnerable older people who live at home (Dutch EASYcare study). J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2008;63:283–90.

Melis RJ, van Eijken MI, Boon ME, Olde Rikkert MG, van Achterberg T. Process evaluation of a trial evaluating a multidisciplinary nurse-led home visiting programme for vulnerable older people. Disabil Rehabil. 2010;32:937–46.

Metzelthin SF, van Rossum E, de Witte LP, Ambergen AW, Hobma SO, Sipers W, et al. Effectiveness of interdisciplinary primary care approach to reduce disability in community dwelling frail older people: cluster randomised controlled trial. BMJ. 2013;347:f5264.

Metzelthin SF, Daniels R, van Rossum E, Cox K, Habets H, de Witte LP, et al. A nurse-led interdisciplinary primary care approach to prevent disability among community-dwelling frail older people: a large-scale process evaluation. Int J Nurs Stud. 2013;50:1184–96.

van Bruggen R, Gorter KJ, Stolk RP, Verhoeven RP, Rutten GE. Implementation of locally adapted guidelines on type 2 diabetes. Fam Pract. 2008;25:430–7.

Weldam SWM, Schuurmans MJ, Zanen P, Heijmans M, Sachs APE, Lammers JJ. The effectiveness of a nurse-led illness perception intervention in COPD patients: a cluster randomised trial in primary care. ERJ Open Res. 2017;3.

Weldam SW, Lammers JJ, Zwakman M, Schuurmans MJ. Nurses' perspectives of a new individualized nursing care intervention for COPD patients in primary care settings: a mixed method study. Appl Nurs Res. 2017;33:85–92.

Review Manager (RevMan). [Computer program]. Version 5.3. Copenhagen: The Nordic Cochrane Centre, The Cochrane Collaboration; 2014.

Higgins J, Green S. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions Version 5.1.0. The Cochrane Collaboration. 2011. www.handbook.cochrane.org. Accessed 10 Jul 2019.

Cochrane Effective Practice and Organisation of Care (EPOC). Suggested risk of bias criteria for EPOC review. EPOC Resources for review authors, 2017. epoc.cochrane.org/resources/epoc-resources-review-authors. Accessed 10 Feb 2018.

Critical Appraisal Skills Programme (CASP). CASP Qualitative Checklist. 2018. https://casp-uk.net/wp-content/uploads/2018/01/CASP-Qualitative-Checklist-2018.pdf. Accessed 10 Jul 2018.

Pluye P, Robert E, Cargo M, Bartlett G, O’Cathain A, Griffiths F, et al. Proposal: a mixed methods appraisal tool for systematic mixed studies reviews. Department of Family Medicine: McGill University, Montreal, Canada; 2011. http://mixedmethodsappraisaltoolpublic.pbworks.com. Accessed 10 Jul 2018.

Fischer F, Lange K, Klose K, Greiner W, Kraemer A. Barriers and strategies in guideline implementation-a scoping review. Healthcare (Basel, Switzerland). 2016;4:E36.

Geerligs L, Rankin NM, Shepherd HL, Butow P. Hospital-based interventions: a systematic review of staff-reported barriers and facilitators to implementation processes. Implement Sci. 2018;13:36.

Kramer L, Schlossler K, Trager S, Donner-Banzhoff N. Qualitative evaluation of a local coronary heart disease treatment pathway: practical implications and theoretical framework. BMC Fam Pract. 2012;13:36.

van Eijken M, Melis R, Wensing M, Rikkert MO, van Achterberg T. Feasibility of a new community-based geriatric intervention programme: an exploration of experiences of GPs, nurses, geriatricians, patients and caregivers. Disabil Rehabil. 2008;30:696–708.

Kovacs E, Strobl R, Phillips A, Stephan AJ, Mueller M, Gensichen J, et al. Systematic review and meta-analysis of the effectiveness of implementation strategies for non-communicable disease guidelines in primary health care. J Gen Intern Med. 2018;33:1142–54.

Craig P, Dieppe P, Macintyre S, Michie S, Nazareth I, Petticrew M. Developing and evaluating complex interventions: the new medical research council guidance. BMJ. 2008;337:a1655.

Vanhaecht K, De Witte K, Sermeus W. The impact of Clinical Pathways on the organisation of care processes: PhD dissertation KULeuven. Katholieke Universiteit Leuven; 2007.

Rotter T, Baatenburg de Jong R, Evans Lacko S, Ronellenfitsch U, Kinsman L. Chapter 12: Clinical pathways as a quality strategy. In: Busse R, Klazinga N, Panteli D, Quentin W, editors. Improving healthcare quality in Europe: Characteristics, effectiveness and implementation of different strategies. Copenhagen: WHO European Observatory on Health Systems and Policies; 2019. p. 309–30.

Acknowledgements

We have to thank Adegboyega K. Lawal for the help in designing and adapting the search strategy.

Funding

This systematic review is part of the “MobilE-PHY” multicentre study, which aims to develop and feasibility test a CPW as a tailored complex intervention to improve mobility and participation among older individuals with vertigo, dizziness and balance disorders in PC.

This study is part of the project “Munich Network Health Care Research - MobilE-NET” and was funded by the German Federal Ministry of Education and Research (grant number 01GY1603C).

This work was also supported by the Bavarian Academic Forum (BayWISS) – Doctoral Consortium “Health Research” and was funded by the Bavarian State Ministry of Science and the Arts.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

ES and MM wrote the study protocol and registered the review with PROSPERO. ES, VR, PB, MM and TR conceived the structure of the systematic review. ES, VR, TR and MM designed the search strategy. ES and VR independently screened the titles and abstracts and assessed the eligibility for inclusion of all identified publications. ES extracted the data and performed a quality assessment of all included studies, and this process was partly duplicated by VR. MM was consulted in case of conflicts. ES corresponded with all other study authors and wrote the drafts of the review. All authors revised the manuscript critically for important intellectual content and read and approved the final version.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Additional file 1.

Overview of literature database search strategies, used search terms, filters and number of results.

Additional file 2.

Methodological quality of included main project reports.

Additional file 3.

Risk of bias summary of RCTs and cRCTs (designed by using RevMan [44]).

Additional file 4.

Overview of critical appraisal tools used for different study designs.

Additional file 5.

Main components of the interventions reported in the included main project reports.

Additional file 6.

Quality assessment results of aspects of the qualitative studies (CASP Checklist).

Additional file 7.

Quality assessment results of aspects of the mixed-method studies (MMAT).

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Seckler, E., Regauer, V., Rotter, T. et al. Barriers to and facilitators of the implementation of multi-disciplinary care pathways in primary care: a systematic review. BMC Fam Pract 21, 113 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12875-020-01179-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12875-020-01179-w