Abstract

Background

People who are diagnosed with both mental and chronic medical illness present unique challenges for the health care system. In resource-limited settings, such as rural India, people with depression and anxiety are often under-served, due to both stigma and lack of trained providers and resources. These challenges can lead to complications in the management of chronic disease as well as increased suffering for patients, families and communities. In this study, we evaluate the effects of integrating mental health and chronic disease treatment of patients in primary health care (PHC) settings using a collaborative care model to improve the screening, diagnosis and treatment of depression in rural India.

Methods

This study is a multi-level randomized controlled trial among patients with depression or anxiety and co-morbid diabetes, or cardiovascular disease. Aim 1 examines whether patients screened at community health-fairs are more likely to be diagnosed and treated for these co-morbid conditions than patients screened after presenting at PHCs. Aim 2 evaluates the impact of collaborative care compared to usual care in a cluster RCT, randomizing at the level of the PHCs. Intervention arm PHC staff are trained in mental health diagnoses, treatment, and the collaborative care model. The intervention also involves community-based “Healthy Living groups” co-led by Ashas, using cognitive-behavioral strategies to promote healthy behaviors. The primary outcome is severity of common mental disorders, with secondary outcomes being diabetes and cardiovascular risk, staff knowledge and patient perceptions.

Discussion

If effective, our results will contribute to the field in five ways: 1) expand on implementation research in low resource settings by examining how multiple chronic diseases can be treated using integrated low-cost, evidence-based strategies, 2) build the capacity of PHC staff to diagnose and treat mental illness within their existing clinic structure and strengthen referral linkages; 3) link community members to primary care through community-based health fairs and healthy living groups; 4) increase mental health awareness in the community and reduce mental health stigma; 5) demonstrate the potential for intervention scale-up and sustainability.

Trial registration

http://Clinicaltrials.gov: NCT02310932 registered December 8, 2014 URL: https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/record/NCT02310932; Clinical Trials Registry India: CTRI/2018/04/013001 retrospectively registered on April 4, 2018.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Chronic, non-communicable diseases have replaced infectious diseases as the number one cause of mortality and disability globally [1,2,3,4,5,6], and mental disorders are among the leading causes of disability worldwide [7]. In India, the prevalence of common mental disorders (CMD) including depressive and anxiety disorders has been estimated to affect 30-34% of primary care patients [3, 8]. The majority of patients with CMD visiting primary health care centers (PHCs) present with multiple somatic symptoms and are often misdiagnosed, resulting in the receipt of ineffective, symptomatic treatments [9, 10]. In a survey of 12,886 patients visiting a clinic in South India who were participating in a community mental health program it was observed that major depressive disorder and dysthymia accounted for 34% and 22%, respectively, of the total burden of mental illness [11]. Although depression can be effectively treated in PHCs in approximately 60-80% cases, only 10-25% of these cases seek treatment [11], typically due to lack of awareness or perceived stigma and discrimination [11, 12].

Mental disorders increase the risk for both communicable and non-communicable diseases and many of these conditions in turn increase the risk for CMDs [13,14,15]. Depression, independent of other risk factors in an otherwise healthy person, increases the risk of developing cardiovascular disease (CVD) and adversely impacts cardiac outcomes [16,17,18]. The depression-CVD co-morbidity not only results in increased mortality but also greater morbidity and disability [19]. Mental disorders and CVD constitute nearly a fifth of the disease burden in India in terms of disability adjusted life years lost [20]. Major coronary risk factors, such as high blood pressure, dyslipidemia, insulin resistance and diabetes are also escalating in this population and correlate positively with the increase in coronary disease [21]. In a study of 103 patients with a recent myocardial infraction attending a cardiology outpatient tertiary care center in Northern India, 25.2% of patients were diagnosed with anxiety or depressive disorder on the Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview (MINI) [22]. Joseph and Srinivasan [23] reported that 23% of patients who presented with chest pain to a tertiary care facility had diagnosable coronary artery disease (CAD), and the psychological distress in CAD was due to co-morbid psychiatric conditions.

Most chronic non-communicable diseases share modifiable behavioral risk factors, including excessive fat and salt intake, sedentary behaviors, and harmful use of alcohol and tobacco consumption [3, 24], making them excellent candidates for integrated intervention programs [25]. The US-based TEAM care study found that integrating depression and chronic disease care among patients with diabetes mellitus (DM) and/or CAD resulted in greater overall 12-month improvement in glycosylated hemoglobin, LDL cholesterol, systolic blood pressure, depressive symptoms, and quality of life [26, 27]. These interventions not only improve outcomes but are cost-effective too [27, 28]. Both the COPES and SUPRIM trials have found that treatment for depression among patients with CAD was associated with a lower risk of secondary cardiovascular events [29, 30]. The rationale behind integration of the management of CMD with CVD and DM is thus four-fold: 1) both are chronic conditions requiring multiple encounters with the health system and adherence to extended duration treatment regimens; 2) there are considerable cross-benefits of the behavioral intervention strategies; 3) integration of mental health services with those provided for CVD and diabetes are cost effective and could contribute to strengthening health systems by providing shared resources [27, 31, 32]; and 4) barriers to effective treatment are similar, including over-medicalization of diagnosis and management, lack of basic screening and diagnostic tools, insufficient affordable financing mechanisms and lack of trained health-care providers [33].

Many resource-constrained setting, including India, face a shortage of physicians and nurses [34]. India has less than one psychiatrist for every 300,000 population [35], however, in rural areas, which account for 70% of India’s population, this ratio has been estimated at less than one per million [35, 36]. The availability of other mental health professionals such as psychologists, social workers and psychiatric nurses is even less, pointing to the need to train PHC providers and community health workers in identifying and treating these disorders [37,38,39]. In response, community lay health workers have been successfully trained to improve a range of physical and mental health outcomes. The content of such programs has ranged from cancer education and screening [40] and asthma management [41] to women’s reproductive health [42]. Shifting to lower-level providers and caregivers for on-going patient support shows promise for achieving better outcomes at lower cost [4, 43, 44]. Though India has a long history of use of community health workers in ‘task-shifting’, this has occurred primarily in the fields of maternal and child health and tuberculosis and less so in the field of chronic diseases. A recent study found that non-physician health workers and ‘expert physicians’ agreed on how to correctly apply the World Health Organization (WHO) Cardiovascular Risk Management Package 80% of the time across PHCs in India and Pakistan [45]. In rural Andhra Pradesh, India, non-physician health workers have been found effective in identifying adults with high cardiovascular risk, by following a simple algorithm [43].

The collaborative care model [46,47,48,49,50,51,52] involving case managers and consulting psychiatrists in support of primary care providers in the treatment of mental disorders has been successful in providing integrated care for mental health and medical illness in PHC settings [13, 47] and was more effective than standard care (50% vs. 19% reduction in depressive symptoms) in U.S clinics among patients aged 60 and older with major depression and/or dysthymic disorder [47]. A meta-analysis of 37 randomized control trials (RCTs) and 12,355 patients showed that both short term and long term outcomes for depression improved significantly for patients in the collaborative care arm [53]. The integrated collaborative care model has also been found to be cost-effective targeting both depression [54] and chronic medical illness, including diabetes [27, 28, 55]. It has been adapted for primary care with different racial and ethnic groups [56], among patients with different co-morbid conditions, including depression and cancer [57], and depression and DM [58]. The collaborative care model has also demonstrated sustainability in PHC settings [26, 59]. While the collaborative care model has been primarily tested in Western settings, a stepped collaborative care model has been used previously [60] in Indian PHCs to treat mental disorders. Our study extends and adapts the integrated collaborative care model for patients diagnosed with depression and chronic medical conditions in limited resource settings.

The protocol described in this article is an ongoing randomized controlled-trial to implement and evaluate a multi-level community based collaborative care model in rural Ramanagaram district in the state of Karnataka, to improve screening, diagnosis, and treatment of depression in India among patients with co-morbid CMD and either DM or CVD at PHC. The aims of our study are; 1) To examine if community-based screenings for depression, anxiety, DM and CVD risk factors during community health fairs (a) increase subsequent diagnosis of these disorders in PHCs; and/or (b) lead to better linkage and retention in care as compared to the standard PHC based screening. We are using accredited social health activists (ASHAs) to raise awareness and provide outreach for the community health fairs; 2) Implement and evaluate the effects of providing staff training to PHC staff in the collaborative care model of integrated mental health (depression and anxiety) and chronic disease (hypertension, DM, and CVD) as compared to the enhanced standard care model. In addition, we are implementing a community-based risk factor reduction groups (Healthy Living Intervention), co-facilitated by ASHAs, to target risk factors common to both mental illness and chronic physical disease, with group session topics in exercise, diet, adherence to medical regimens, ocial support, coping skills, and problem solving skills; 3) evaluate the effects of the clinic and community-based intervention for co-morbid primary care patients compared to the enhanced standard treatment services.

Methods

Study design and overview

As shown in Fig. 1, the study was designed to implement and evaluate the effects of a collaborative care intervention on the screening, diagnosis and treatment of depression among rural Indians with depression or anxiety and either hypertension, diabetes or CVD, who live in villages associated with 50 PHCs in rural Karnataka. The design of randomized controlled trial is described below and compares 1) the enhanced health fair screening condition to standard PHC screening; and 2) community-based and collaborative care to enhanced standard treatment.

Ethics approval was obtained from the Institutional Ethical Review Board at St. John’s Medical College and Hospital and Committee on Human Research, University of California, San Francisco. All adverse events are identified by trained field staff and assessed by the Principal Investigators. Participants with adverse events are referred to the medical officer at the PHC and or at district hospital for immediate medical intervention as appropriate. Deaths are reported to the St. John’s Institutional Ethics Committee, UCSF IRB, and the Data Safety and Monitoring Board within 5-10 days per protocols approved by the IRBs, the funder and the government of India. Possibly study-related non-serious adverse events are reported to the respective ethics review board by the principal investigators, according to protocol. This study is monitored by a Data Safety and Monitoring Board which consists of a psychiatrist, an expert in community medicine/rural health and a statistician with experience conducting RCTs. The board reviews all procedures biannually related to the protection of study participants, including confidentiality procedures and reports of adverse events. The board has access to data to determine if the trial can continue or needs to be terminated.

Conceptual framework

We used a multi-level framework based on previous literature on collaborative care to improve screening diagnosis and treatment of depression in primary health settings, and our own extensive work in community medicine and behavior change in India to guide our adaption of the primarily western collaborative care model. Our intervention offers several key innovations for treatment of co-morbid patients by identifying and targeting common risk factors with the help of ASHA and by training PHC staff in the collaborative care model. The “healthy living” intervention described below uses a novel package of evidence-based strategies in a group setting. Our multi-level intervention represents a timely, novel, sustainable and comprehensive approach to co-morbid diagnosis and disease management by integrating multiple existing health care staff and structures into a continuum of care through community based screenings, linkage to and retention in care and ongoing support through the use of community-based groups and mobile technology.

We incorporated constructs from the Social Ecological Model [61,62,63,64,65,66] and Social Cognitive Theory [67, 68] because of its emphasis on both interpersonal interactions as well as on specific strategies that promote behavior change; all important to reducing symptoms of depression, anxiety and stress and to increasing health promoting behaviors. In particular, the following three features of this theory guide the delivery of our intervention 1) people and their environments interact continuously, and behaviors are the result of this dynamic bi-directional interaction. Our intervention facilitates this interaction through ASHA at the community level through health fairs, PHC staff at the clinic level, and social support through healthy living groups; 2) By including group-based activities, participants can learn from and motivate each other; 3) The intervention emphasizes skills building, while assisting participants to break down challenges into manageable components necessary to enable sustainable behaviors.

Setting and randomization

This study is conducted in collaboration with 50 PHCs in rural Ramanagara district of Karnataka state in southern India, each PHC serves a population of 30,000. A typical PHC has a medical officer, pharmacist, staff nurses, female multipurpose health workers (auxiliary nurse-midwives), male multipurpose health workers, ASHA workers, a laboratory technician/assistant, driver and helpers. It includes both outpatient and inpatient areas with four to six beds, as well as space for counseling, minor emergencies, a labor room, a pharmacy and a laboratory. The PHCs were assigned an identification number, and 25 PHCs were randomly assigned by the study statistician using a pseudo-random number generator to the enhanced screening arm linked to community health fairs and the remaining 25 were assigned to the standard screening arm. Subsequently, half of the enhanced screening and standard screening PHCs were randomly assigned to the collaborative care arm and the remaining half was assigned to the standard care treatment condition (Fig. 1). Participants randomized to the intervention group will be stratified by gender. While participants and intervention staff are not blinded, assessment staff are blinded to group assignment.

Enhanced screening vs standard screening conditions

The “enhanced” screening condition is implemented in 25 of our 50 PHC catchment areas, allowing us to examine whether the added community-based screening through community health fairs a) increases identification of patients with co-morbid diagnosis (Table 1); and b) improves linkage to and retention in care, compared to co-morbid patients identified via standard PHC-based screening. Specific recruitment procedures for each setting are described below, followed by common screening procedures and tests.

At the enhanced screening PHCs, nurses and ASHA run health fairs in villages that are a part of our collaborating PHC catchment areas. Prior to conducting the fairs, ASHAs raise awareness and provide outreach of the upcoming health fair through announcements at community events and meetings, poster, brochures, and door-to-door visits to community members. One health fair is held per week during the five-week recruitment period. The health fair provides an opportunity for people in the community to receive a free health check-up.

Screening occurs in two phases, during the initial screening and confirmatory screening (Table 1). The initial screening is held at the health fair or at the associated PHCs in the enhanced screening condition and at the PHC only for the standard screening condition. Interested patients give written informed consent to study staff for the screenings, and those meeting the eligibility criteria during the initial screening are invited to a confirmatory screening at the PHC. Patients who meet the eligibility criteria during the confirmatory screening are invited to participate in the study. Eligible participants receive information about the study verbally as well as in written form if literate, including details about the intervention, study protocol, randomization process, time commitment and potential risks and benefits. Participants are informed that participation is voluntary, there are no negative consequences for refusing to participate, and that consent can be withdrawn at any time during the study without any repercussions. Participants receive a copy of the study information sheet and informed consent. Illiterate participants have an option of providing verbal consent or a thumb print. In those cases, a witness, unaffiliated with the study, also signs the consent form.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Participants, who are 30 or older, with co-morbid CMD (Depression or Anxiety Disorder) and either hypertension, diabetes, or ischemic heart disease, and who are willing and able to consent and be followed for 12 months are considered eligible for inclusion in the study.

Collaborative care intervention design

The proposed multi-level “Healthy Living” intervention has been designed to promote long-term mental and physical health among the participants, by training PHC staff and ASHAs in the collaborative, stepped care model and by providing patients with skills that can be incorporated into their lifestyles. The stepped care model includes referrals of suicidal patients to the district psychiatrist and additional referrals for abnormal lab values, and the support of our psychiatry consultants during their weekly calls. The content and format are guided by our conceptual model [64, 66, 69, 70] and include strategies that can be easily integrated into existing health care structures and that have been found effective in previous studies [27, 28, 32, 39, 55, 59, 60, 69,70,71,72,73,74,75,76,77].

Collaborative care staff training

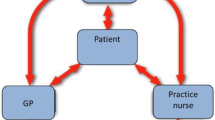

Staff in the 25 intervention PHCs receive training sessions in the collaborative care model [26] by psychiatrists from St John’s Medical College, who have volunteered to take on the role of “consultant psychiatrist” [78]. The PHC staff training is designed to enable them to effectively integrate treatment of CMDs into their regular practice in patients with co-morbid medical conditions. A modified version of the IMPACT model [48, 78] was adapted for our setting to maximize the likelihood of sustainability. PHC staffs are required to undergo one full day of interactive group training. The morning session trains all PHC staffs on management of chronic non-communicable diseases at the clinic level and the second half focuses on collaborative care in mental health. Primary care physicians are trained to identify and treat patients presenting with a CMD. The PHC nurses are trained to function as “care managers,” and help with tracking patient progress. Support is also being provided by the consulting psychiatrists, who provide both routine caseload, diagnostic, and treatment consultation for difficult cases, which may include referral recommendations when additional care is needed. Other care team members include the PHC pharmacist, trained to educate patients and their caregivers about their medication regimen, side effects and adherence. Finally, the ASHAs are trained in risk factor screening and modification, and act as a liaison between the PHC, patients, families and community. They co-facilitate the healthy living groups and provide appointment reminders through home visits.

Clinic-based intervention

Participants in the 25 intervention PHCs, receive diagnostic test and clinical treatment for both their mental illness and chronic disease by the PHC care team trained in comprehensive integrated mental health and CVD care using the stepped collaborative care model described above [39, 74].

Community-based intervention

Participants in the intervention PHCs are given an appointment to participate in a 12-month, healthy living group, designed to target risk factors important in management of depression, anxiety, DM, and CVD (Table 2). Each group includes eight to 10 same-sex participants and held in an easily accessible venue in the community. The first 12 weekly sessions are facilitated by a master’s level counselor and co-facilitated by an ASHA, who subsequently provides nine monthly sessions focused on behavior maintenance. The behavioral change strategies used are based on principles of social cognitive theory, such as observational learning, setting manageable goals, practice and getting feedback, building self-efficacy and skills training [69, 70].

Session format

Each begins with breathing exercises for relaxation known to be effective in both CMD and CVD [79, 80]. The interrelationship between thoughts, emotions, behaviors and their impact of health are discussed to set the stage for the introduction of cognitive techniques. A list of common stressful life situations are developed by the group and used as examples for subsequent problem-solving skills training and coping skills training. Participants are encouraged to set both short term and longer-term goals and to make a commitment to change at the end of every session and reviewed and reinforced in the following-section. In addition, participants are also encouraged to set up buddy systems within the group and establish informal peer support networks.

We anticipate that our integrated intervention will have both direct and indirect beneficial effects on the families and communities associated with the Intervention PHCs. ASHAs involved with the integrated intervention groups meet with every participant’s family during bi-monthly home visits and encourage them to support the participant’s new healthy lifestyle. Participants themselves are encouraged to act as dissemination agents by sharing the knowledge and skills learned during the Healthy Living groups with their families.

Implementation and adherence to intervention protocols are documented and monitored through weekly reports of HLG sessions, weekly psychiatry consultation calls between PHC medical officers and the consulting psychiatrist, and through observation of the intervention sessions by an independent monitor who completes a check-list to ensure that all components are covered. In addition, the intervention coordinator makes weekly visits to the PHCs to ensure that all participants are appropriately referred for care. All intervention staff are trained and certified in all components of the intervention.

“Enhanced” standard treatment

All staff in the PHCs that have been randomized to Enhanced Standard Treatment will receive a full day of basic training in established clinical protocols set by the state of Karnataka. For ethical reasons, since standard PHC treatment often includes inappropriate use of vitamins and anxiolytics, a psychiatrist leads the afternoon session training on how to treat CMDs per standard treatment protocols.

Patients in the standard treatment arm will receive usual care per the standardized protocols developed by the State. We will also ensure that any patient who is diagnosed as moderately to severely depressed has access to effective anti-depressant medication by referring eligible patients to a psychiatrist located in the nearest district hospital. Patients identified as at high risk for suicide are also referred to district hospital psychiatrists at screening and assessments per study protocol. In addition, any abnormal clinical results (e.g. hypertension, DM, etc.) found at screening and cohort assessments receive an appropriate referral.

Outcome measures and schedule

The vast majority of the study measures have been used previously in India. Remaining measures (internalized stigma of mental illness, patient satisfaction and clinical vignettes), were adapted and pilot tested during our start-up phase to ensure that they are appropriate for our specific study population and setting. All measures have been translated into Kannada and back translated.

All cohort participants are assessed at baseline, 6 weeks, 3 months, 6 months and 12 months. To minimize attrition, we collect extensive contact information from all participants at enrollment. This includes mobile phone numbers, as well as street addresses, information about landmarks, and the name and phone number of someone who always knows how to reach them. This information is verified and updated during each assessment visit, HLG sessions visit and tracking phone calls and visits. All research materials will be coded with ID numbers only and linked to contact information on a separately stored document kept under lock and key.

To examine if community-based health fair screenings increases subsequent diagnoses in the PHC of patients with co-morbid mental health and chronic disease diagnoses, we use the Kessler-10 [81], MINI [82], and the clinical measures for diabetes and CVD outlined in Table 1. To screen for psychological distress at the initial screening using the Kessler-10, a brief standardized questionnaire that correlates with other commonly used depression screening questionnaires and with the DSM IV diagnoses of both depression and anxiety disorders [81, 83]. At the subsequent confirmatory screening, MINI is used to confirm the diagnosis of anxiety or depressive disorder as per DSM-IV guidelines. We also assess suicidal ideation based on items from the MINI and refer participants at high suicidal risk to the district psychiatrist for further management and treatment.

Linkage and retention in care is measured by the proportion of participants who started treatment and the proportion of these participants who were retained in care throughout the study.

To evaluate the effects of the clinic and community-based intervention for co-morbid primary care patients compared to the enhanced standard treatment services we measure severity of anxiety and depressive symptoms, blood pressure, body mass index and measures for diabetes and cardiac conditions (Table 3).

Severity of anxiety and depressive symptoms

The Generalized Anxiety Disorder Scale (GAD-7) [84] and the Patient Health Questionnaire Depression Scale (PHQ-9) is used to assess severity of anxiety and depression, respectively [85].

Blood pressure (BP)

Systolic and diastolic blood pressure is measured using a standardized protocol. Two measurements are taken and the average of the two readings is calculated [86, 87]. Hypertension is defined as elevated blood pressure (average systolic BP (SBP) ≥ 140 mmHg and/or an average diastolic BP (DBP) ≥90 mmHg) or higher levels of hypertension if SBP ≥ 160 mmHg and/or an DBP ≥ 95 mmHg.

Body Mass Index (BMI) is calculated as weight (kg) divided by height (m2) [78]. Waist circumference is measured in centimeters.

Measures of diabetes and cardiac risk

Lipids (total cholesterol, LDL, HDL and triglycerides), kidney function (serum creatinine, urine creatinine and urine microalbumin) and glycemic control (HbA1c) are measured using standard assays. Dyslipidemia are defined as: LDL > 130 or HDL < 40 mg/dL [88]. We selected HbA1c because it is not affected by short-term dietary changes and strongly correlates with disease severity [89].

Collaborative care PHC staff training outcome measures

Knowledge and Skills related to collaborative care are assessed using clinical vignettes followed by a set of questions on CMD and CVD screening, treatment, case management, communication, & use of consultation and referrals, tailored to each type of health professional at the PMC. Vignettes are effective in evaluating the benefits of training [90,91,92,93] including mental health training among primary care physicians in India [94].

Patient perceptions

To minimize socially desirable responses [95], we developed and administer a behaviorally anchored measure that targets patient perceptions of staff in terms of 1) patient interactions; 2) providing relevant information; 3) active listening and answering questions; and 4) addressing risk behaviors.

All data collected in interviews and laboratory tests are de-identified and uploaded to an encrypted password protected database. Double data entry occurs within 3 days of data collection. The data are monitored on an ongoing basis for completeness and accuracy.

Statistical analyses

Preliminary analyses will include examination of the reliability of scales (e.g. PHQ-9, GAD-7), attrition analyses to compare respondents with complete data to those who do not complete the study with regard to group assignment and baseline demographics, and comparisons between the two intervention arms, to check for group balance. We will use chi-square tests for unordered categorical variables, Kruskal Wallis tests for ordinal or non-normal continuous data, and ANOVA for normal continuous variables.

Screening

To test the hypothesis that, compared to standard screening, enhanced screening will result, on an average, in more people being identified as co-morbid for CMD and CVD/DM during the confirmatory testing at the PHC, we will use a Poisson regression model - or in case of over dispersion, a negative binomial model - with PHC as the unit of analysis, and population size in the catchment area of the PHC included as an offset.

Secondary analysis will explore subsequent linkage and retention in care of enrolled participants first screened at the community health fairs compared to those first screened at PHC. These participants will be compared by examining the proportion of participants who started treatment both by the 6 week follow-up, as well as the proportion retained throughout the study. We will use a mixed-effects logistic regression model with a random intercept for PHC.

Intervention

The primary, intention-to-treat (ITT) analyses will evaluate the impact of the intervention, both in terms of a) return to below-threshold levels for CMD and CVD/DM risk (i.e. dichotomized outcomes), and b) improvement in the levels of the continuous CMD and CVD/DM measures (depression and anxiety scores, BP, HbA1c, LDL, and serum creatinine levels) via logistic and linear mixed-effects regression models respectively, with repeated measures nested within individuals, and individuals nested within PHC, and random intercepts for individuals and PHC [96, 97]. The trajectories of the continuous variables will be examined via the time-by-intervention interaction effect. We will run separate regressions for the various outcomes, to allow us to detect if different variables react to the intervention at different rates. To prevent Type I error inflation, we will lower α accordingly. In all models covariates will be included as necessary.

The sample size of 1250 in each intervention arm (50 participants per PHC), was determined based on achieving 80% power for the ITT analyses regarding the effect of the intervention, and was calculated as follows: we assumed an attrition rate of 20%, and an intra-class correlation (ICC) of 0.1 to account for clustering of participants in PHCs, which reduces the initial sample size to an effective sample size of n = 204/group. Pooling data across the three post-intervention measurements triples this number, and subsequent adjustment for repeated measures with an assumed ICC = 0.5, results in a final effective sample size of n = 306 person-time observations per group. Based on previous research, we assumed 40% of control group participants to recover [98, 99]. With α = .025, the minimum detectable effect size at 80% power is 12% more of the intervention group participants recovering [100]. This is a small effect size according to Cohen [101], and comparable to earlier studies in the US [26]. To test the screening hypothesis, with 25 PHCs per screening condition, 80% power and α = 0.05, the minimum detectable effect in a Poisson regression is 2.1 times as many co-morbid cases identified with the enhanced compared to the standard screening [102]. Although this is a large effect, we deemed it attainable, given the documented under-reporting of mental health in standard care [10, 11], and the intensive nature of our enhanced screening.

Current status of the study

Intervention and assessments are ongoing as of August 3, 2018. During the final year of our research, a dissemination meeting will be held for key stakeholders including local, state, and national government officials, and hospital administration officials.

Discussion

This randomized controlled trial evaluates the effectiveness of multi-level integrated clinic and community-based intervention model for common mental disorders co-morbid with diabetes and cardiovascular conditions compared to enhanced care as usual. In addition, we test the effectiveness of using ASHAs as link workers between the community and the PHC in increasing referrals of such patients to the clinic and improving retention rate in the treatment regimen. A novel feature of this proposal includes group sessions that target risk behaviors common to both depression and co-morbid medical conditions. Our intervention builds on collaborative care model and is dependent on trained PHC physicians to deliver evidence based intervention for both CMD and co-morbid medical conditions and directly addresses the scarcity of trained mental health professionals in rural India. It has a high potential for scale up and sustainability as it builds on strengthening the linkages between the community and the existing Government programs.

Abbreviations

- ASHA:

-

Accredited social health activist

- BMI:

-

Body mass index

- BP:

-

Blood pressure

- CAD:

-

Coronary artery disease

- CMD:

-

Common mental disorder

- CVD:

-

Cardiovascular disease

- DM:

-

Diabetes mellitus

- GAD:

-

Generalized anxiety disorder

- ITT:

-

Intention to treat

- MINI:

-

Mini international neuropsychiatric interview

- PHC:

-

Primary health center

- PHQ:

-

Patient health questionnaire

- RCT:

-

Randomized controlled trial

- WHO:

-

World Health Organization

References

Global status report on non-communicable diseases. World Health Organization (WHO). 2010. http://www.who.int/nmh/publications/ncd_report_full_en.pdf.

Taylor D. The burden of non-communicable disease in India. Hamilton ON: The Cameron Institute; 2010.

Patel V, Chatterji S, Chisholm D, Ebrahim S, Gopalakrishna G, Mathers C, et al. Chronic diseases and injuries in India. Lancet. 2011;377:413–28.

Abegunde DO, Mathers CD, Adam T, Ortegon M, Strong K. The burden and costs of chronic diseases in low-income and middle-income countries. Lancet. 2007;370:1929–38.

Nair H, Shu XO, Volmink J, Romieu I, Spiegelman D. Cohort studies around the world: methodologies, research questions and integration to address the emerging global epidemic of chronic diseases. Public Health. 2012;126:202–5.

Hay SI, Abajobir AA, Abate KH, Abbafati C, Abbas KM, Abd-Allah F, et al. Global, regional, and national disability-adjusted life-years (DALYs) for 333 diseases and injuries and healthy life expectancy (HALE) for 195 countries and territories, 1990-2016: a systematic analysis for the global burden of disease study 2016. Lancet. 2017;390:1260–344.

Whiteford HA, Degenhardt L, Rehm J, Baxter AJ, Ferrari AJ, Erskine HE, et al. Global burden of disease attributable to mental and substance use disorders: findings from the global burden of disease study. Lancet. 2010;382:1575–86.

Pothen M, Kuruvilla A, Philip K, Joseph A, Jacob KS. Common mental disorders among primary care attenders in Vellore, South India: nature, prevalence and risk factors. Int J Soc Psychiatry. 2003;49:119–25.

Jacob KS. The diagnosis and management of depression and anxiety in primary care: the need for a different framework. Postgrad Med J. 2006;82:836–9.

Srinivasan K, Isaacs A, Villanueva E, Lucas A, Raghunath D. Medical attribution of common mental disorders in a rural Indian population. Asian J Psychol. 2010;3:142–4.

Srinivasan K, Isaacs A, Thomas T, Jayaram G. Outcomes of common mental disorders in a rural community in South India. Indian J Social Psych. 2006;22:110–5.

Maulik PK, Tewari A, Devarapalli S, Kallakuri S, Patel A. The systematic medical appraisal, referral and treatment (SMART) mental health project: development and testing of electronic decision support system and formative research to understand perceptions about mental health in rural India. PLoS One. 2016;11:e0164404.

Srinivasan K. “Blues” ain’t good for the heart. Indian J Psychiatry. 2011;53:192–4.

Prince M, Patel V, Saxena S, Maj M, Maselko J, Phillips MR, et al. No health without mental health. Lancet. 2007;370:859–77.

Read JR, Sharpe L, Modini M, Dear BF. Multimorbidity and depression: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Affect Disord. 2017;221:36–46.

Wulsin LR, Singal BM. Do depressive symptoms increase the risk for the onset of coronary disease? A systematic quantitative review. Psychosom Med. 2003;65:201–10.

Van der Kooy K, van Hout H, Marwijk H, Marten H, Stehouwer C, Beekman A. Depression and the risk for cardiovascular diseases: systematic review and meta analysis. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2007;22:613–26.

Daskalopoulou M, George J, Walters K, Osborn DP, Batty GD, Stogiannis D, et al. Depression as a risk factor for the initial presentation of twelve cardiac, cerebrovascular, and peripheral arterial diseases: data linkage study of 1.9 million women and men. PLoS One. 2016;11:e0153838.

Bigger JT, Glassman AH. The American Heart Association science advisory on depression and coronary heart disease: an exploration of the issues raised. Cleve Clin J Med. 2010;77(Suppl 3):S12–9.

Burden of disease in India. background paper. National Commission on macroeconomics and health (NCMH), Ministry of Health and Family Welfare. New Delhi: Government of India; 2005.

Gupta R, Rastogi P, Hariprasad D, Mathur B, Bhardwaj A. Coronary heart diseases and risk factors in a rural population of India. South Asian J Prev Cardiol. 2003;7:4-8

Sarkar S, Chadda RK, Kumar N, Narang R. Anxiety and depression in patients with myocardial infarction: findings from a Centre in India. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2012;34:160–6.

Srinivasan K, Joseph W. A study of lifetime prevalence of anxiety and depressive disorders in patients presenting with chest pain to emergency medicine. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2004;26:470–4.

Cecchini M, Sassi F, Lauer JA, Lee YY, Guajardo-Barron V, Chisholm D. Tackling of unhealthy diets, physical inactivity, and obesity: health effects and cost-effectiveness. Lancet. 2010;376:1775–84.

Beaglehole R, Epping-Jordan J, Patel V, Chopra M, Ebrahim S, Kidd M, et al. Improving the prevention and management of chronic disease in low-income and middle-income countries: a priority for primary health care. Lancet. 2008;372:940–9.

Katon WJ, Lin EH, Von Korff M, Ciechanowski P, Ludman EJ, Young B, et al. Collaborative care for patients with depression and chronic illnesses. N Engl J Med. 2010;363:2611–20.

Katon W, Russo J, Lin EH, Schmittdiel J, Ciechanowski P, Ludman E, et al. Cost-effectiveness of a multicondition collaborative care intervention: a randomized controlled trial. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2012;69:506–14.

Katon W, Unutzer J, Fan MY, Williams JW Jr, Schoenbaum M, Lin EH, et al. Cost-effectiveness and net benefit of enhanced treatment of depression for older adults with diabetes and depression. Diabetes Care. 2006;29:265–70.

Davidson KW, Rieckmann N, Clemow L, Schwartz JE, Shimbo D, Medina V, et al. Enhanced depression care for patients with acute coronary syndrome and persistent depressive symptoms: coronary psychosocial evaluation studies randomized controlled trial. Arch Intern Med. 2010;170:600–8.

Gulliksson M, Burell G, Vessby B, Lundin L, Toss H, Svardsudd K. Randomized controlled trial of cognitive behavioral therapy vs standard treatment to prevent recurrent cardiovascular events in patients with coronary heart disease: secondary prevention in Uppsala primary health care project (SUPRIM). Arch Intern Med. 2011;171:134–40.

Samb B, Desai N, Nishtar S, Mendis S, Bekedam H, Wright A, et al. Prevention and management of chronic disease: a litmus test for health-systems strengthening in low-income and middle-income countries. Lancet. 2010;376:1785–97.

Katon W, Lyles CR, Parker MM, Karter AJ, Huang ES, Whitmer RA. Association of depression with increased risk of dementia in patients with type 2 diabetes: the diabetes and aging study. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2012;69:410–7.

Mendis S, Abegunde D, Oladapo O, Celletti F, Nordet P. Barriers to management of cardiovascular risk in a low-resource setting using hypertension as an entry point. J Hypertens. 2004;22:59–64.

Rao M, Rao KD, Kumar AK, Chatterjee M, Sundararaman T. Human resources for health in India. Lancet. 2011;377:587–98.

Jacob KS, Sharan P, Mirza I, Garrido-Cumbrera M, Seedat S, Mari JJ, et al. Mental health systems in countries: where are we now? Lancet. 2007;370:1061–77.

Jacob ME, Abraham VJ, Abraham S, Jacob KS. The effect of community based daycare on mental health and quality of life of elderly in rural South India: a community intervention study. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2007;22:445–7.

Khandelwal SK, Jhingan HP, Ramesh S, Gupta RK, Srivastava VK. India mental health country profile. Int Rev Psychiatry. 2004;16:126–41.

Eaton J, McCay L, Semrau M, Chatterjee S, Baingana F, Araya R, et al. Scale up of services for mental health in low-income and middle-income countries. Lancet. 2011;378:1592–603.

Patel V, Araya R, Chatterjee S, Chisholm D, Cohen A, De Silva M, et al. Treatment and prevention of mental disorders in low-income and middle-income countries. Lancet. 2007;370:991–1005.

Wadler BM, Judge CM, Prout M, Allen JD, Geller AC. Improving breast cancer control via the use of community health workers in South Africa: a critical review. J Oncol. 2011;2011:H382–7.

Viswanathan M, Kraschnewski J, Nishikawa B, Morgan LC, Thieda P, Honeycutt A, et al. Outcomes of community health worker interventions: evidence report/technology assessment no. 181 (Prepared by the RTI International-University of North Carolina Evidence-based Practice Center under Contract No. 290 2007 10056 I.) AHRQ publication no. 09-E014. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. 2009.

Gogia S, Sachdev HS. Home visits by community health workers to prevent neonatal deaths in developing countries: a systematic review. Bull World Health Organ. 2010;88:658–6B.

Chow CK, Joshi R, Gottumukkala AK, Raju K, Raju R, Reddy S, et al. Rationale and design of the rural Andhra Pradesh cardiovascular prevention study (RAPCAPS): a factorial, cluster-randomized trial of 2 practical cardiovascular disease prevention strategies developed for rural Andhra Pradesh, India. Am Heart J. 2009;158:349–55.

Joshi R, Alim M, Kengne AP, Jan S, Maulik PK, Peiris D, et al. Task shifting for non-communicable disease management in low and middle income countries--a systematic review. PLoS One. 2014;9:e103754.

Abegunde DO, Shengelia B, Luyten A, Cameron A, Celletti F, Nishtar S, et al. Can non-physician health-care workers assess and manage cardiovascular risk in primary care? Bull World Health Organ. 2007;85:432–40.

Unutzer J, Katon W, Williams JW Jr, Callahan CM, Harpole L, Hunkeler EM, et al. Improving primary care for depression in late life: the design of a multicenter randomized trial. Med Care. 2001;39:785–99.

Unutzer J, Katon W, Callahan CM, Williams JW Jr, Hunkeler E, Harpole L, et al. Collaborative care management of late-life depression in the primary care setting: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2002;288:2836–45.

Unutzer J, Powers D, Katon W, Langston C. From establishing an evidence-based practice to implementation in real-world settings: IMPACT as a case study. Psychiatr Clin North Am. 2005;28:1079–92.

Levine S, Unutzer J, Yip JY, Hoffing M, Leung M, Fan MY, et al. Physicians’ satisfaction with a collaborative disease management program for late-life depression in primary care. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2005;27:383–91.

Grypma L, Haverkamp R, Little S, Unutzer J. Taking an evidence-based model of depression care from research to practice: making lemonade out of depression. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2006;28:101–7.

Hegel M, Imming J, Cyr-Provost M, Hitchcock-Noel P, Arean P, Unutzer J. Role of allied behavioral health professionals in a collaborative stepped care treatment model for depression in primary care: project IMPACT. Fam Syst Health. 2002;20(3);265–77.

Simon G. Collaborative care for depression. BMJ. 2006;332:249–50.

Gilbody S, Bower P, Fletcher J, Richards D, Sutton AJ. Collaborative care for depression: a cumulative meta-analysis and review of longer-term outcomes. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166:2314–21.

Unutzer J, Katon WJ, Fan MY, Schoenbaum MC, Lin EH, Della Penna RD, et al. Long-term cost effects of collaborative care for late-life depression. Am J Manag Care. 2008;14:95–100.

Katon WJ, Schoenbaum M, Fan MY, Callahan CM, Williams J Jr, Hunkeler E, et al. Cost-effectiveness of improving primary care treatment of late-life depression. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2005;62:1313–20.

Richardson L, McCauley E, Katon W. Collaborative care for adolescent depression: a pilot study. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2009;31:36–45.

Fann JR, Fan MY, Unutzer J. Improving primary care for older adults with cancer and depression. J Gen Intern Med. 2009;24(Suppl 2):S417–24.

Williams JW Jr, Katon W, Lin EH, Noel PH, Worchel J, Cornell J, et al. The effectiveness of depression care management on diabetes-related outcomes in older patients. Ann Intern Med. 2004;140:1015–24.

Katon W, Unutzer J, Wells K, Jones L. Collaborative depression care: history, evolution and ways to enhance dissemination and sustainability. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2010;32:456–64.

Patel VH, Kirkwood BR, Pednekar S, Araya R, King M, Chisholm D, et al. Improving the outcomes of primary care attenders with common mental disorders in developing countries: a cluster randomized controlled trial of a collaborative stepped care intervention in Goa, India. Trials. 2008;9:4.

Sallis J, Owen N. Physical activity and behavioral medicine. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications; 1999.

Walcott-McQuigg JA, Zerwic JJ, Dan A, Kelley MA. An ecological approach to physical activity in African American women. Medscape Womens Health. 2001;6:3.

Banks-Wallace J. Staggering under the weight of responsibility: the impact of culture on physical activity among African American women. J Multicult Nurs Health. 2000;6:24–30.

Stokols D. Translating social ecological theory into guidelines for community health promotion. Am J Health Promot. 1996;10:282–98.

Smedley B, Syme L. Promoting health: intervention strategies from social and behavioral research. Inst Med. 2000.

Fleury J, Lee SM. The social ecological model and physical activity in African American women. Am J Community Psychol. 2006;37:129–40.

Bandura A. Social cognitive theory and exercise of control over HIV infection. In: DiClemente R, Peterson JL, editors. Preventing AIDS: theories and methods of behavioral interventions. New York: Plenum; 1994. p. 25–59.

Bandura A. Social learning theory. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall; 1977.

Bandura A. Social cognitive theory and personality. In: Pervin LA, John OP, editors. Handbook of personality: theory and research. New York: Guilford Press; 1999. p. 154–96.

Bandura A. Health promotion by social cognitive means. Health Educ Behav. 2004;31:143–64.

Nyamathi AM, William RR, Ganguly KK, Sinha S, Heravian A, Albarran CR, et al. Perceptions of women living with AIDS in rural India related to the engagement of HIV-trained accredited social health activists for care and support. J HIV AIDS Soc Serv. 2010;9:385–404.

Nyamathi AM, Sinha S, Ganguly KK, William RR, Heravian A, Ramakrishnan P, et al. Challenges experienced by rural women in India living with AIDS and implications for the delivery of HIV/AIDS care. Health Care Women Int. 2011;32:300–13.

Nyamathi A, Heravian A, Zolt-Gilburne J, Sinha S, Ganguly K, Liu E, et al. Correlates of depression among rural women living with AIDS in southern India. Issues Ment Health Nurs. 2011;32:385–91.

Katon W, Von Korff M, Lin E, Simon G, Walker E, Unutzer J, et al. Stepped collaborative care for primary care patients with persistent symptoms of depression: a randomized trial. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1999;56:1109–15.

Katon W, Lin EH, Von Korff M, Ciechanowski P, Ludman E, Young B, et al. Integrating depression and chronic disease care among patients with diabetes and/or coronary heart disease: the design of the TEAMcare study. Contemp Clin Trials. 2010;31:312–22.

Patel V, Simon G, Chowdhary N, Kaaya S, Araya R. Packages of care for depression in low- and middle-income countries. PLoS Med. 2009;6:e1000159.

Patel V, Araya R, Chowdhary N, King M, Kirkwood B, Nayak S, et al. Detecting common mental disorders in primary care in India: a comparison of five screening questionnaires. Psychol Med. 2008;38:221–8.

Stommel M, Schoenborn CA. Accuracy and usefulness of BMI measures based on self-reported weight and height: findings from the NHANES & NHIS 2001-2006. BMC Public Health. 2009;9:421.

Strachowski D, Khaylis A, Conrad A, Neri E, Spiegel D, Taylor CB. The effects of cognitive behavior therapy on depression in older patients with cardiovascular risk. Depress Anxiety. 2008;25:E1–10.

Dekker RL. Cognitive behavioral therapy for depression in patients with heart failure: a critical review. Nurs Clin North Am. 2008;43:155–70. viii

Kessler RC, Andrews G, Colpe LJ, Hiripi E, Mroczek DK, Normand SL, et al. Short screening scales to monitor population prevalences and trends in non-specific psychological distress. Psychol Med. 2002;32:959–76.

Sheehan DV, Lecrubier Y, Sheehan KH, Amorim P, Janavs J, Weiller E, et al. The Mini-international neuropsychiatric interview (M.I.N.I.): the development and validation of a structured diagnostic psychiatric interview for DSM-IV and ICD-10. J Clin Psychiatry. 1998;59(Suppl 20):22–33. quiz 4-57

Andrews G, Slade T. Interpreting scores on the Kessler psychological distress scale (K10). Aust N Z J Public Health. 2001;25:494–7.

Hamilton M. The assessment of anxiety states by rating. Br J Med Psychol. 1959;32:50–5.

Hamilton M. A rating scale for depression. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1960;23:56–62.

Pickering TG, Hall JE, Appel LJ, Falkner BE, Graves J, Hill MN, et al. Recommendations for blood pressure measurement in humans and experimental animals: part 1: blood pressure measurement in humans: a statement for professionals from the Subcommittee of Professional and Public Education of the American Heart Association Council on high blood pressure research. Circulation. 2005;111:697–716.

Pickering T. The measurement of blood pressure in developing countries. Blood Press Monit. 2005;10:11–2.

Grundy SM, Becker D, Clark LT, Cooper RS, Denke MA, Howard J, Hunninghake DB, Illingworth DR, Luepker RV, McBride P, McKenney JM. Detection, evaluation, and treatment of high blood cholesterol in adults (Adult Treatment Panel III). Circulation. 2002;106(25):3143–421.

Kern D. American Diabetes Association’s new clinical practice recommendations promote A1C as diagnostic test for diabetes. American Diabetes Association. 2009; http://www.diabetes.org/newsroom/press-releases/2009/cpr-2010-a1c-diagnostic-tool.html. Accessed 14 June 2012

Veloski J, Tai S, Evans AS, Nash DB. Clinical vignette-based surveys: a tool for assessing physician practice variation. Am J Med Qual. 2005;20:151–7.

Peabody JW, Tozija F, Munoz JA, Nordyke RJ, Luck J. Using vignettes to compare the quality of clinical care variation in economically divergent countries. Health Serv Res. 2004;39:1951–70.

Peabody JW, Luck J, Glassman P, Dresselhaus TR, Lee M. Comparison of vignettes, standardized patients, and chart abstraction: a prospective validation study of 3 methods for measuring quality. JAMA. 2000;283:1715–22.

Luck J, Peabody JW, Lewis BL. An automated scoring algorithm for computerized clinical vignettes: evaluating physician performance against explicit quality criteria. Int J Med Inform. 2006;75:701–7.

Sriram TG, Chandrashekar CR, Isaac MK, Srinivasa Murthy R, Kishore Kumar KV, Moily S, et al. Development of case vignettes to assess the mental health training of primary care medical officers. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1990;82:174–7.

Pandya SK. Doctor-patient relationship: the importance of the patient's perceptions. J Postgrad Med. 2001;47:3–7.

Rabe-Hesketh S, Skrondal A. Multilevel and longitudinal modeling using STATA. 2nd ed. College Station, TX: Stata Press; 2008.

Snijders T, Bosker R. Multilevel analysis: an introduction to basic and advanced multilevel modeling. London: Sage; 1999.

Araya R, Rojas G, Fritsch R, Gaete J, Rojas M, Simon G, et al. Treating depression in primary care in low-income women in Santiago, Chile: a randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2003;361:995–1000.

Patel V, Chisholm D, Rabe-Hesketh S, Dias-Saxena F, Andrew G, Mann A. Efficacy and cost-effectiveness of drug and psychological treatments for common mental disorders in general health care in Goa, India: a randomised, controlled trial. Lancet. 2003;361:33–9.

Dupont WD, Plummer WD Jr. Power and sample size calculations. A review and computer program. Control Clin Trials. 1990;11:116–28.

Cohen J. Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences. Hillsdale, NJ: L. Erlbaum Associates; 1988.

Hintze J. Pass 11: NCSS, LLC; 2011. www.ncss.com

Katzman R, Brown T, Fuld P, Peck A, Schechter R, Schimmel H. Validation of a short orientation-memory-concentration test of cognitive impairment. Am J Psychiatry. 1983;140:734–9.

Rose G, McCartney P, Reid DD. Self-administration of a questionnaire on chest pain and intermittent claudication. Br J Prev Soc Med. 1977;31:42–8.

Heatherton TF, Kozlowski LT, Frecker RC, Fagerstrom KO. The Fagerstrom test for nicotine dependence: a revision of the Fagerstrom tolerance questionnaire. Br J Addict. 1991;86:1119–27.

Ebbert JO, Patten CA, Schroeder DR. The Fagerstrom test for nicotine dependence-smokeless tobacco (FTND-ST). Addict Behav. 2006;31:1716–21.

Saunders JB, Aasland OG, Babor TF, de la Fuente JR, Grant M. Development of the alcohol use disorders identification test (AUDIT): WHO collaborative project on early detection of persons with harmful alcohol consumption--II. Addiction. 1993;88:791–804.

Bharathi AV, Kurpad AV, Thomas T, Yusuf S, Saraswathi G, Vaz M. Development of food frequency questionnaires and a nutrient database for the prospective urban and rural epidemiological (PURE) pilot study in South India: methodological issues. Asia Pac J Clin Nutr. 2008;17:178–85.

Hagstromer M, Oja P, Sjostrom M. The international physical activity questionnaire (IPAQ): a study of concurrent and construct validity. Public Health Nutr. 2006;9:755–62.

Ekstrand ML, Chandy S, Heylen E, Steward W, Singh G. Developing useful highly active antiretroviral therapy adherence measures for India: the Prerana study. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2010;53:415–6.

Schmitt A, Gahr A, Hermanns N, Kulzer B, Huber J, Haak T. The diabetes self-management questionnaire (DSMQ): development and evaluation of an instrument to assess diabetes self-care activities associated with glycaemic control. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2013;11:138.

Malda M. There is no place like home: on the relation between culture and children’s cognition. Unpublished. 2009.

Development of the World Health Organization WHOQOL-BREF quality of life assessment. Psychol Med. 1998;28:551–8.

Livingston JD, Boyd JE. Correlates and consequences of internalized stigma for people living with mental illness: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Soc Sci Med. 2010;71:2150–61.

Acknowledgements

We would like to acknowledge the Government of Karnataka, Directorate of Health and Family Welfare Service for the permission to conduct this study.

Funding

This work was supported by the US National Institute of Mental Health [R01MH100311]. The sponsor had no role in the design of the study or the writing of the manuscript. It does not have a role in the collection, analysis, or interpretation of the data.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

KS and ME conceptualized the paper and AM, KS, and ME drafted the manuscript. KS, ME, MW, and PM contributed substantially to the conception of the study design and intervention, and contributed to draft revisions; All authors reviewed the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Ethics approval was obtained from the Institutional Ethical Review Board at St. John’s Medical College and Hospital (reference 38/2013) and Committee on Human Research, University of California, San Francisco (reference 125,781). Informed consent to participate in this study is obtained from all participants. Interested and eligible participants receive information about the study verbally as well as in written form. Participants are informed that participation is voluntary, there are no negative consequences for refusing to participate, and that consent can be withdrawn at any time during the study without any repercussions. Interested participants provide written consent. Illiterate participants have an option of providing verbal consent or a thumb print and a witness, unaffiliated with the study, also signs the consent form.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Srinivasan, K., Mazur, A., Mony, P.K. et al. Improving mental health through integration with primary care in rural Karnataka: study protocol of a cluster randomized control trial. BMC Fam Pract 19, 158 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12875-018-0845-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12875-018-0845-z