Abstract

Background

Regardless of patients’ baseline renal function, worsening renal function (WRF) during hospitalization is associated with poor outcomes. In individuals with acute heart failure (AHF), one predictor of WRF is an early drop in systolic blood pressure (SBP). Few studies have investigated WRF in elderly AHF patients or the influence of these patients’ heart rate (HR) at admission on the relationship between an early SBP drop SBP and the AHF.

Methods

We measured the SBP and HR of 245 elderly AHF inpatients (83 ± 6.0 years old, females 51%) at admission and another six times over the next 48 h. We defined ‘WRF’ as a serum creatinine increase ≥0.3 mg/dL by Day 5 post-admission. We calculated the ‘early SBP drop’ as the difference between the admission SBP value and the lowest value during the first 48 h of hospitalization.

Results

There were significant differences between the 36 patients with WRF and the 209 patients without WRF: early SBP drop (51 vs. 33 mmHg, p < 0.01) and HR at admission (79 vs. 90 bpm, p < 0.05), respectively. In the multiple logistic regression analysis adjusted for the confounders, higher early SBP drop (p < 0.04) and lower HR at admission (p < 0.01) were significantly associated with WRF. No significant association was shown for the interaction term of early SBP drop × HR at admission with WRF.

Conclusions

In these elderly AHF patients, exaggerated early SBP drop and lower HR at admission were significant independent predictors of WRF, and these factors were additively associated with WRF.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Approximately one-third of individuals with acute heart failure (AHF) experience worsening renal function (WRF) during hospitalization [1,2,3], and it has been demonstrated that WRF has a strong association with poorer patient outcomes regardless of the patients’ baseline renal function [1,2,3,4,5]. It is thus crucial to identify patients who are at risk of developing WRF, at the earliest point possible. Higher blood pressure (BP) at a patient’s admission to a hospital was shown to be linked to a greater risk of WRF [3, 6, 7], and a drop in a patient’s systolic blood pressure (SBP) during the first days post-admission has also been shown to pose a risk of the development of WRF [1, 8, 9] and to be associated with the prognosis [9, 10]. It was suggested that AHF patients’ baseline heart rate (HR) can be used to predict in-hospital cardiac mortality, and in contrast to patients with chronic heart failure (CHF), among AHF patients a lower HR at baseline was shown to be associated with a higher in-hospital rate of cardiac death [4].

Few investigations have examined the relationships among WRF, early SBP drop, and the HR at admission in elderly patients with AHF. Herein, we tested our hypothesis that an early drop in the SBP of an elderly AHF patient could be used to predict WRF in the patient. We also investigated the effect of HR at admission on any interactions among these factors.

Methods

Study population

This prospective observational cohort study was conducted at Hiroshima City Asa Hospital from January 2013 to December 2015. We considered a patient as eligible for study enrollment if he or she were hospitalized for AHF during this study. AHF was defined as a rapid onset or worsening of symptoms and/or signs of heart failure (HF). The HF symptoms were: fatigue, breathlessness, and ankle swelling. The signs were: peripheral edema, elevated jugular venous pressure, and pulmonary crackles [11, 12]. Each patient’s diagnosis of AHF was based on the 2016 guidelines of the European Society of Cardiology for the diagnosis of heart failure [12].

Regarding the B-type natriuretic peptide (BNP) used for the diagnosis of AHF, we set an exclusion cut-off point at 100 pg/mL based on current guidelines [12]. Each AHF diagnosis was made by experienced cardiologists. We excluded patients with multiple organ failure, shock, or sepsis, and those who were on chronic hemodialysis. The consecutive eligible elderly patients with AHF over 70 years of age were enrolled after the purpose of study was fully explained to the patients.

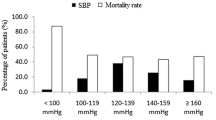

Clinical scenario

The clinical scenario is based on initial SBP on admission and other symptoms, and is one of the most commonly used clinical classifications [13]. In summary, AHF patients were divided into five groups: clinical scenario 1 (SBP > 140 mmHg with dyspnea and/ or congestion), clinical scenario 2 (SBP 100–140 mmHg with dyspnea and/or congestion), clinical scenario 3 (SBP < 100 mmHg with dyspnea and/or congestion), clinical scenario 4 (signs of acute coronary syndrome with dyspnea and/or congestion), and clinical scenario 5 (isolated right ventricular failure) [13]. This classification is useful in determining initial treatment (e.g., non-invasive positive pressure ventilation, vasodilators, inotropes, and diuretics). This urgent/immediate approach shortens the length of hospital stay and reduces in-hospital mortality in terms of shortening the time to the start treatment [14, 15].

Procedures

The physician investigators were not prohibited from using any standard medication thought necessary to treat the enrolled patients, including additional vasodilators [1]. Participants’ BP and HR were measured at admission, and six more recordings were performed within 48 h of admission. At every recording, BP and HR were measured 3 times, and the mean values of the second and third readings at each recording were used. At the baseline and 12 h later, serum creatinine was measured. After that point, serum creatinine was measured daily through Day 5 post-admission [1].

Definitions

We defined ‘WRF’ as a ≥ 0.3 mg/dL increase in the patient’s serum creatinine level compared to his or her baseline value, at any time through Day 5 [1]. We examined the potential ‘early drop in SBP’ as the difference between the patient’s SBP value taken at admission and the lowest SBP value measured during the first 48 h of hospitalization [1]. For all of the BP measurements, the patient was supine and had rested for ≥5 min.

Statistical analyses

The data are presented as the mean ± the standard deviation (SD) or as a percentage, and all analyses were performed with SPSS ver. 11.5 J software (SPSS, Chicago, IL). We used the Chi-squared test to compare categorical variables among groups, and we performed one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) for the continuous variables to tested the null hypothesis that the means of early SBP drop and HR at admission were same between the group with WRF and that without WRF. To estimate and test the independent effects of early SBP drop and the HR at admission on WRF, we conducted a multiple logistic regression analysis. In addition to the patient age, gender and other possible confounders, those factors that would contribute to the outcome in the initial univariable analyses at p values of less than 0.1 were considered as candidate variables for the multivariable model. As the distribution of BNP was highly skewed, log transformation was carried out. Probability (p)-values < 0.05 were accepted as significant.

Results

Patient characteristics

The 491 patients with AHF admitted to hour hospital from January 2013 to December 2015, and we included 251 elderly patients with AHF in this study. While 3 patients who were not able to collect blood sample were excluded, 3 patients who were not able to measure blood pressure were excluded. Ultimately, we analyzed 245 patients in this study. Figure 1 summarizes the flow of potential participants.

Creatinine values that allowed a classification of WRF were available for all 245 of the enrolled patients: mean age 82.9 ± 6.0 years, 124 females (50.6%), 121 males (49.4%). This study population was consisted from a mix of 166 patients with newly arisen (“de novo”) AHF (66%) and 79 patients with acutely decompensated chronic heart failure (34%). Among all patients, 78.3% had a history of hypertension, and 11.8% had ischemic heart failure. There were patients with the 3 patients with sinus bradycardia (1.2%), 12 patients with sinoatrial block (4.9%) and 8 patients with atrio-ventricular block (3.3%). According to with and without WRF, there were no significant difference in sinus bradycardia (p = 0.4), sinoatrial block (p = 0.5) or atrio-ventricular block (p = 0.2).

Prevalence and clinical correlates of WRF

WRF was confirmed in 14.7% (n = 36) of the 245 evaluable patients. Table 1 summarizes the characteristics of patients with and without WRF. Compared to the 209 patients without WRF (85.3%), those with WRF had significantly higher prevalences of a history of hypertension, intravenous loop diuretic use, and intravenous nitroglycerin use; in addition, the WRF group had significantly higher baseline SBP values, significantly lower HR at admission, and significantly greater early drops in SBP through the first 48 h post-admission (Table 1).

Factors associated with worsening renal function on univariate analysis

As shown in Table 2, in the univariate logistic regression analysis, the following were significantly associated with WRF: hypertension (odds ratio [OR] 3.48; 95% confidence interval [CI] 1.02–11.8), intravenous nitroglycerin (OR 3.18; 95%CI 1.54–6.58), SBP at admission (OR 1.02; 95%CI 1.01–1.03), HR at admission (OR 0.987; 95%CI 0.97–0.999), and early SBP drop (OR 1.02; 95%CI 1.01–1.03).

Determinants of WRF

The results of our multiple logistic regression analysis are presented in Table 3. The analysis was adjusted for the following confounders: patient age and gender, the left ventricular ejection fraction, the presence/absence of hypertension, beta-blocker use at baseline and log BNP, intravenous loop diuretic, isosorbide dinitrate and carperitide use. The two factors that were significantly associated with WRF were the patient’s HR at admission (adjusted OR [AOR] 0.98; 95%CI 0.96–0.99) and early SBP drop (AOR 1.02; 95%CI 1.004–1.03) (Table 3). The interaction term of early SBP drop × HR at admission was not significantly associated with WRF (p = 0.3).

Discussion

The results of this observational study demonstrated that a greater drop in SBP within the first 48 h after the hospitalization of an elderly patient with AHF — as well as the patient’s HR at admission — were independently associated with a higher risk of the occurrence of WRF. This is the first investigation to report associations of an early SBP drop and the HR at admission with WRF in patients with AHF.

Early SBP drop and WRF

Our findings revealed that an early SBP drop after hospitalization in elderly patients with AHF was an independent determinant of the development of WRF. In the univariate analyses conducted in prior studies, the baseline SBP level itself was found to be positively correlated with WRF, and in those studies [6, 7], a higher risk of WRF during hospitalization was observed in AHF patients with hypertension. Forman et al. [3] reported that an SBP value at admission > 160 mmHg was independently associated with an increased WRF risk. In the present study, although the baseline SBP level was significantly positively correlated with the early SBP drop (r = 0.82, p < 0.001), not baseline SBP level (OR 1.015; 95%CI 0.999–1.03; p = 0.062) but early SBP drop remained independently related to a higher risk of WRF when either the baseline SBP level or the early SBP drop was included in the multiple regression model. This result suggests that a larger drop in SBP (and not a higher baseline SBP) was a significant risk factor for WRF in this series of elderly AHF patients.

We suspect that our present findings might be due to the auto-regulatory response in the kidneys [16]. The kidneys’ vascular system will constrict (its afferent arterioles, specifically) when the renal perfusion pressure rises because of an increase in BP; the kidneys’ inter-lobal arteries may also constrict. Afferent vasodilation occurs when the BP drops, and if the BP falls further, efferent vasoconstriction can also occur. The kidneys are thus able to maintain — over a wide range of BP values — constant glomerular capillary perfusion, pressure, and filtration. The pre-glomerular circulation of patients with long-standing hypertension has shown a blunted ability to dilate in response to a drop in SBP, and this can result in an exaggerated decrease in the intraglomerular pressure [17]. Our present observation that a higher drop in SBP is related to a higher risk of WRF is consistent with the above explanation, but our findings remain to be confirmed in further studies.

Although our results indicate that the use of an intravenous loop diuretic or isosorbide dinitrate during a patient’s hospital admission might be positively associated with WRF, neither loop diuretic nor isosorbide dinitrate use was shown to be a significant indicator of WRF in the multivariate model. Diuretics are known to present a risk of impaired kidney function in patients with heart failure, probably by a so-called ‘tubuloglomerular feedback’ mechanism. The distal tubules of the kidneys sense a loss of salt, and this leads to a release of adenosine, which then binds to the adenosine A1-receptor. Afferent vasoconstriction is the result, with a subsequent reduction in the renal blood flow (a main determinant of renal function in heart failure patients) [18].

Nitrate is thought to dilate the renal microvascular flow and increase the renal blood flow when other aspects of the vascular status are normal. However, a systemic vasodilation of the systemic vasculature might completely decrease the renal blood flow in accord with an acute SBP reduction. Each deleterious impact of diuretics or nitrate on the renal blood flow would thus be observed in an AHF population such as our present patients, because both diuretics and nitrate would contribute to a higher drop in SBP during the acute phase of HF.

HR at admission and WRF

Our analyses revealed that the at-admission HR values of the elderly patients with AHF were independently associated with a higher risk of WRF. This finding confirms that a lower HR at admission may be a marker and may also pose a direct increased risk of WRF in AHF patients [19]. In individuals with chronic HF, elevated resting HR was reported to be associated with increased risks of cardiovascular disease and mortality [20, 21]. In the hyperacute phase of AHF, tachycardia is a mostly beneficial physiological compensatory response. An increase in the HR is necessary to maintain the cardiac output, due to structural limitations of the stroke volume [22].

Although the details of the relationship between the pathophysiology of AHF and the HR remain unknown [23], our present data demonstrate that a lower HR at baseline in patients with AHF was associated with a much higher risk of WRF. Bainbridge showed in 1915 that rapid volume loading results in increases of both blood pressure and heart rate [24], and a 2009 review showed that a higher baseline SBP is associated with a better outcome [25]. We speculate that in the urgent phase of AHF, a higher risk of WRF might be associated with an impaired ability to increase the heart rate to appropriate levels.

It should be noted that we did not observe a significant association between WRF and the interaction term of early SBP drop × HR at admission. We thus suggest that the early SBP drop and HR at admission each have an additive impact on WRF rather than a synergistic effect.

Study limitations

This study is subject to regression dilution bias due to measurement error associated with high intra-person variability in HR and SBP. This bias is likely to have led to an underestimation in the strength of the association between either HR or SBP and WRF. This study could not refute the possibility of significant interaction between early SBP drop and HR at admission because there might not be enough power to detect that interaction. There is possibility of residual confounding because every possible confounder could not be adjusted for.

Conclusion

Among the 245 elderly patients hospitalized for AHF, WRF was independently predicted by a greater drop in SBP during the first 48 h of hospitalization. The patients’ HR at admission also independently predicted WRF. An early SBP drop and the HR at admission might serve as additive surrogate markers of clinical outcomes in AHF patients.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets generated during and/or analysed during the current study are not publicly available due to data privacy regulation by Hiroshima City Asa Hospital.

Abbreviations

- WRF:

-

Worsening renal function

- AHF:

-

Acute heart failure

- BP:

-

Blood pressure

- SBP:

-

Systolic blood pressure

- HR:

-

Heart rate

- CHF:

-

Chronic heart failure

- BNP:

-

B-type natriuretic peptide

- SD:

-

Standard deviation

- ANOVA:

-

Analysis of variance

- OR:

-

Odds ratio

- CI:

-

Confidential interval

References

Voors AA, Davison BA, Felker GM, Ponikowski P, Unemori E, Cotter G, Teerlink JR, Greenberg BH, Filippatos G, Teichman SL, Metra M. Early drop in systolic blood pressure and worsening renal function in acute heart failure: renal results of pre-RELAX-AHF. Eur J Heart Fail. 2011;13:961–7.

Damman K, Navis G, Voors AA, Asselbergs FW, Smilde TD, Cleland JG, van Veldhuisen DJ, Hillege HL. Worsening renal function and prognosis in heart failure: systematic review and meta-analysis. J Card Fail. 2007;13:599–608.

Forman DE, Butler J, Wang Y, Abraham WT, O’Connor CM, Gottlieb SS, Loh E, Massie BM, Rich MW, Stevenson LW, Young JB, Krumholz HM. Incidence, predictors at admission, and impact of worsening renal function among patients hospitalized with heart failure. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2004;43:61–7.

Herout PM, Harshaw Q, Phatak H, Saka G, McNeill A, Wu D, Sazonov V, Desagun R, Shirani J. Impact of worsening renal function during hospital admission on resource utilization in patients with heart failure. Am J Cardiol. 2010;106:1139–45.

Metra M, Cotter G, Senger S, Edwards C, Cleland JG, Ponikowski P, Cursack GC, Milo O, Teerlink JR, Givertz MM, O'Connor CM, Dittrich HC, Bloomfield DM, Voors AA, Davison BA. Prognostic significance of creatinine increases during an acute heart failure admission in patients with and without residual congestion: a post hoc analysis of the PROTECT. Circ Heart Fail. 2018;11:e004644.

Owan TE, Hodge DO, Herges RM, Jacobsen SJ, Roger VL, Redfield MM. Secular trends in renal dysfunction and outcomes in hospitalized heart failure patients. J Card Fail. 2006;12:257–62.

Logeart D, Tabet JY, Hittinger L, Thabut G, Jourdain P, Maison P, Tartiere JM, Solal AC. Transient worsening of renal function during hospitalization for acute heart failure alters outcome. Int J Cardiol. 2008;127:228–32.

Arao Y, Sawamura A, Nakatochi M, Okumura T, Kato H, Oishi H, Yamaguchi S, Haga T, Kuwayama T, Yokoi T, Hiraiwa H, Kondo T, Morimoto R, Murohara T. Early blood pressure reduction by intravenous vasodilators is associated with acute kidney injury in patients with hypertensive acute decompensated heart. Circ J. 2019;83:1883–90.

Cotter G, Metra M, Davison BA, Jondeau G, Cleland JGF, Bourge RC. VERITAS investigators: systolic blood pressure reduction during the first 24 h in acute heart failure admission: friend or foe? Eur J Heart Fail. 2018;20:317–22.

Kitai T, Tang WHW, Xanthopoulos A, Murai R, Yamane T, Kim K, Oishi S, Akiyama E, Suzuki S, Yamamoto M, Kida K, Okumura T, Kaji S, Furukawa Y, Matsue Y. Impact of early treatment with intravenous vasodilators and blood pressure reduction in acute heart failure. Open Heart. 2018;5:e000845.

Mebazaa A, Yilmaz MB, Levy P, Ponikowski P, Peacock WF, Laribi S, Ristic AD, Lambrinou E, Masip J, Riley JP, McDonagh T, Mueller C, de Filippi C, Harjola VP, Thiele H, Piepoli MF, Metra M, Maggioni A, McMurray J, Dickstein K, Damman K, Seferovic PM, Ruschitzka F, Leite-Moreira AF, Bellou A, Anker SD, Filippatos G. Recommendations on pre-hospital and early hospital management of acute heart failure: a consensus paper from the Heart Failure Association of the European Society of Cardiology, the European Society of Emergency Medicine and the Society of Academic Emergency Medicine. Eur J Heart Fail. 2015;17:544–58.

Ponikowski P, Voors AA, Anker SD, Bueno H, Cleland JGF, Coats AJS, Falk V, González-Juanatey JR, Harjola VP, Jankowska EA, Jessup M, Linde C, Nihoyannopoulos P, Parissis JT, Pieske B, Riley JP, Rosano GMC, Ruilope LM, Ruschitzka F, Rutten FH, van der Meer P, ESC Scientific Document Group.;. Task Force Members. 2016 ESC guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure: the task force for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC): developed with the special contribution of the heart failure association (HFA) of the ESC. Eur Heart J. 2016;37:2129–200.

Mebazaa A, Gheorghiade M, Piña IL, Harjola VP, Hollenberg SM, Follath F, Rhodes A, Plaisance P, Roland E, Nieminen M, Komajda M, Parkhomenko A, Masip J, Zannad F, Filippatos G. Practical recommendations for prehospital and early in-hospital management of patients presenting with acute heart failure syndromes. Crit Care Med. 2008;36:S129–39.

Emerman CL. Treatment of the acute decompensation of heart failure: efficacy and pharmacoeconomics of early initiation of therapy in the emergency department. Rev Cardiovasc Med. 2003;4:S13–20.

Peacock WF, Emerman CL. Emergency department management of patients with acute decompensated heart failure. Heart Fail Rev. 2004;9:187–93.

Guyton AC. The relationship of cardiac output and arterial pressure control. Circulation. 1981;64:1079–88.

Palmer BF. Renal dysfunction complicating the treatment of hypertension. N Engl J Med. 2002;347:1256–61.

Damman K, Navis G, Smilde TD, Voors AA, van der Bij W, van Veldhuisen DJ, Hillege HL. Decreased cardiac output, venous congestion and the association with renal impairment in patients with cardiac dysfunction. Eur J Heart Fail. 2007;9:872–8.

Kajimoto K, Sato N, Keida T, Sakata Y, Asai K, Mizuno M, Takano T. and on behalf of the investigators of the acute decompensated heart failure syndromes (ATTEND) registry: low admission heart rate is a marker rather than a mediator of increased in-hospital mortality for patients with acute heart failure syndromes in sinus rhythm. Int J Cardiol. 2014;171:98–100.

Palatini P, Julius S. Heart rate and the cardiovascular risk. J Hypertens. 1997;15:3–17.

Fox K, Borer JS, Camm J, Danchin N, Ferrari R, Lopez Sendon JL, Steg PG, Tardif JC, Tavazzi L, Tendera M. Heart rate working group: resting heart rate in cardiovascular disease. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2007;50:823–30.

Francis GS, Goldsmith SR, Ziesche S, Nakajima H, Cohn JN. Relative attenuation of sympathetic drive during exercise in patients with congestive heart failure. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1985;5:832–9.

Peterson PN, Rumsfeld JS, Liang L, Albert NM, Hernandez AF, Peterson ED, Fonarow GC, Masoudi FA. American Heart Association get with the guidelines-heart failure program: a validated risk score for in-hospital mortality in patients with heart failure from the American Heart Association get with the guidelines program. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2010;3:25–32.

Bainbridge FA. The influence of venous filling upon the rate of the heart. J Physiol. 1915;50:65–84.

Gheorghiade M, Pang PS. Acute heart failure syndromes. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2009;53:557–73.

Acknowledgements

Preliminary data for this study were presented at the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) congress 2019 in Paris, abstract P4548 [Eur Heart J 2019, 40 (Supple1): ehz745.0939].

Funding

None.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

MT, MN and KD contributed to the conception of the study; MT, MN, MK, NO, EK1, EK2 and AY with EK1 corresponding to Eiji Kunita significantly to the data analysis and manuscript preparation; MN performed data analyses and wrote the manuscript; YK, HS, AO and HK contributed to the design and statistical analysis of this study. All authors have read and approved the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The study protocol was approved by the Hiroshima City Asa Hospital Research Committee, Hiroshima, Japan and was conducted in accordance with the principles stated in the Declaration of Helsinki. All participants provided informed written consent.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Takeuchi, M., Nagai, M., Dote, K. et al. Early drop in systolic blood pressure, heart rate at admission, and their effects on worsening renal function in elderly patients with acute heart failure. BMC Cardiovasc Disord 20, 366 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12872-020-01656-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12872-020-01656-1