Abstract

Background

Three to five percent of patients with acute myocardial infarction (AMI) have normal coronary arteries on invasive coronary angiography (ICA). The aim of this study was to assess the presence and characteristics of atherosclerotic plaques on computed tomography coronary angiography (CTCA) and describe the clinical characteristics of this group of patients.

Methods

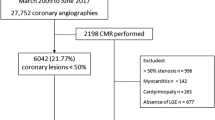

This was a multicentre, prospective, descriptive study on CTCA evaluation in thirty patients fulfilling criteria for AMI and without visible coronary plaques on ICA. CTCA evaluation was performed head to head in consensus by two experienced observers blinded to baseline patient characteristics and ICA results. Analysis of plaque characteristics and plaque effect on the arterial lumen was performed. Coronary segments were visually scored for the presence of plaque. Seventeen segments were differentiated, according to a modified American Heart Association classification. Echocardiography performed according to routine during the initial hospitalisation was retrieved for analysis of wall motion abnormalities and left ventricular systolic function in most patients.

Results

Twenty-five patients presented with non ST-elevation myocardial infarction (NSTEMI) and five with ST-elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI). Mean age was 60.2 years and 23/30 were women. The prevalence of risk factors of coronary artery disease (CAD) was low. In total, 452 coronary segments were analysed. Eighty percent (24/30) had completely normal coronary arteries and twenty percent (6/30) had coronary atherosclerosis on CTCA. In patients with atherosclerotic plaques, the median number of segments with plaque per patient was one. Echocardiography was normal in 4/22 patients based on normal global longitudinal strain (GLS) and normal wall motion score index (WMSI); 4/22 patients had normal GLS with pathological WMSI; 3/22 patients had pathological GLS and normal WMSI; 11/22 patients had pathological GLS and WMSI and among them we could identify 5 patients with a Takotsubo pattern on echo.

Conclusions

Despite a diagnosis of AMI, 80 % of patients with normal ICA showed no coronary plaques on CTCA. The remaining 20 % had only minimal non-obstructive atherosclerosis. Patients fulfilling clinical criteria for AMI but with completely normal ICA need further evaluation, suggestively with magnetic resonance imaging (MRI).

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Acute myocardial infarction usually results from thrombotic occlusion of a coronary artery due to a ruptured atherosclerotic plaque. However, about 3 to 5 % of patients [1, 2] fulfil criteria for myocardial infarction but have angiographically normal coronary arteries (MINCA). The pathogenetic mechanisms involved in the development of AMI in the patient with no visible coronary atherosclerosis on the ICA are unclear.

Alterations in the endothelium and/or components in the blood promoting endothelial dysfunction and the formation of thrombotic occlusion have been suggested [3, 4]. According to Glagov [5] atherosclerotic plaques can cause outward remodelling of the coronary vessel without significant obstruction and therefore can be invisible on ICA. However, such plaques are prone to rupture and manifest as an acute myocardial infarction [6]. Other proposed mechanisms are coronary dissection, embolism and vasospasm [7–9] as well as spontaneous thrombus resolution [10].

Although ICA has been the gold standard for the diagnosis of coronary artery disease, lumenography provides merely an image of the internal arterial lumen and lacks the capability to adequately depict the vessel wall with its developing atherosclerotic plaque. Previous studies analysing serial angiograms from patients presenting with acute coronary syndrome (ACS) have suggested that in nearly two thirds of the culprit lesions, the coronary angiogram obtained a few months before the acute event demonstrated a non-significant stenosis [11].

Imaging of the coronary vessels with computed tomography has been proposed as a method for qualitative imaging of vessel wall changes [12]. CTCA has a high negative predictive value, but tends to overestimate the degree of stenosis [13–15]. Previous studies have shown that CTCA is comparable to intravascular ultrasound (IVUS) for classifying plaques [16–18].

This group of patients with acute myocardial infarction and angiographically normal coronary arteries is broadly recognised and described in previous studies [19, 20]. They are often described as being younger than the “classical” myocardial infarction patients and have lower burden of cardiovascular risk factors but the pathogenesis of this kind of presentation of myocardial infarction is still debatable.

We hypothesised that atherosclerotic plaques will be detected by CTCA in patients with acute myocardial infarction and completely normal coronary arteries on ICA. This is an extension and refinement of prior work in this area, which has tended to include significant numbers of patients with non-obstructive atheroma on ICA, even stenosis with 30–50 % reduction in lumen diameter [19, 20].

Methods

Study design

This was a multicentre, prospective, descriptive study carried out in 3 hospitals in southeast Sweden, Linköping, Kalmar and Jönköping, from November 2008 to January 2011. Patients were included at the local hospital where they presented with myocardial infarction and underwent an ICA which showed completely normal coronary arteries. After inclusion they were referred to the University Hospital in Linköping for the CTCA part of the study. Inclusion criteria for the study were: myocardial infarction according to the ESC guidelines of 2007 [including significant rise and/or fall of cardiac troponin with at least one value above the 99th percentile of upper limit of normal (ULN), clinical features consistent with ischemia (various combinations of chest, upper extremity, mandibular or epigastric discomfort or an ischaemic equivalent such as dyspnoea or fatigue) and/or ischemic ECG changes] with no visible atherosclerosis on ICA as assessed by two independent experienced operators [21]. Patients with a reasonable alternative explanation for their symptoms and elevated troponin were not included in the study after adjudication. The exclusion criteria were: inability to perform CTCA (contraindications to beta-blockers or nitroglycerine, hypersensitivity to contrast medium, pregnancy and permanent atrial fibrillation), renal dysfunction (eGFR <60 ml/min) or risk factors for contrast induced acute kidney injury (treatment with metformin, high dose diuretics), recent major trauma, surgery or percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI).

Troponin analysis

Three different troponin assay methods were used during the course of the study according to local routines. Troponin I (Stratus CS, Siemens, ULN: 0,07 μg/L), Troponin T (AQT 90, Radiometer, ULN: 0,01 μg/L) and hs-Troponin T (Elecsys/Cobas, Roche Diagnostics, ULN: 15 ng/L).

Computed tomography coronary angiography, image acquisition

CTCA was performed at the University Hospital Linköping using a 64-slice or a 128-slice dual source CT scanner (Somatom Definition or Somatom Definition Flash, Siemens Healthcare, Forchheim, Germany). During CTCA acquisition non-ionic contrast medium was administered, 60–50 ml, 370 mg I/ml, 5 ml/sec, Jopromid. Intravenous beta-blockers were administered for optimal image quality. Additionally, nitroglycerine was administered to all patients before the scan. Strategies to reduce radiation dose, including electrocardiogram gated tube current modulation, prospective triggering and reduction of tube voltage were used whenever feasible.

The following scan parameters were used for 64 slice CT scanner: 64 × 2 slices with 0.6 mm collimation, gantry rotation time of 330 ms, tube voltage 100 or 120 mV, and effective tube current of 320 to 412 mAs. The following settings were used for the 128-slice CT scanner: 128 × 2 slices with 0.6 mm collimation, gantry rotation time of 280 ms, tube voltage 100 or 120 mV, and effective tube current of 320 to 370 mAs.

Computed tomography coronary angiography, image analysis

CTCA datasets were evaluated on a remote workstation with dedicated software (QAngio CT, Medis Medical Imaging Systems, Leiden, the Netherlands) [22]. Evaluation was performed side by side in consensus by two experienced observers blinded to baseline patient characteristics and ICA results. Analysis of plaque characteristics and plaque effect on the arterial lumen was performed at a predefined window and level setting (window 900, level 250 Hounsfield units) [23]. If considered necessary, display settings were manipulated in order to achieve optimal discrimination of vessel lumen and plaque components and minimise blooming artefacts of calcified plaques. Coronary segments were visually scored for the presence of plaque. Seventeen segments were differentiated, according to a modified American Heart Association classification [24]. Tissue structures >1 mm2 either within the coronary artery lumen or adjacent to the coronary artery lumen which could be discriminated from surrounding pericardial tissue, epicardial fat, or the vessel lumen, were defined as coronary plaques. The degree of stenosis of atherosclerotic lesions was quantified by visual estimation. Plaques with ≥50 % luminal narrowing were classified as obstructive. Plaques were classified according to their composition into three types: 1. Non-calcified plaque (plaques with low density compared to contrast-enhanced lumen), 2. calcified plaque (plaques with high density structures compared to the contrast-enhanced lumen), or 3. mixed plaque (non-calcified and calcified elements in single plaque). The accuracy for detecting atherosclerosis using CTCA is very high [25].

Echocardiography

An echocardiography subgroup consisting of 22 patients, where images could be retrieved for analysis of wall motion abnormalities and left ventricular systolic function and five additional patients where only the written echo report was available, was studied. Three patients were not examined by echocardiography or the data is missing. Echocardiography was performed with GE Vivid E7, E9, Vivid-I, Siemens Sequoia or Philips IE33. All recordings were imported into Siemens US Syngo Workplace v. 3.5 and analysed with the VVI software. For image analysis, the endocardial border of the left ventricle was traced from the mitral annulus to the apex and back to the contralateral annulus. If tracking was satisfactory, longitudinal strain data was stored in Excel. Three tracings per view were acquired and the mean global value calculated. Values higher than −17 were regarded as pathological. In addition, a wall motion score index was calculated based on the scoring of each segment in terms of 1 = normal, 2 = hypokinetic, 3 = akinetic and 4 = dyskinetic wall motion. The index was 1.0 if all segments were deemed normal.

Statistical analysis

Continuous variables are presented as mean ± SD when normally distributed and as medians with interquartile range (IQR) when skewed. Categorical variables are presented as numbers and percentages. Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS version 20 (Chicago, IL).

Ethics

The study complies with the Declaration of Helsinki. Approval was obtained from the Regional Ethical Review Board in Linköping (Dnr M72-08). All participants gave written informed consent.

Results

Clinical results

Thirty patients were enrolled in the study. Patient characteristics are displayed in Table 1.

Twenty-five patients presented with NSTEMI and five with STEMI. Mean age of the study population was 60.2 years (51.3–69.1) and 23/30 (77 %) were female. 17/30 (57 %) were previous or active smokers, 7/30 (23 %) had hypertension, 5/30 (17 %) had hypercholesterolemia and none had diabetes. There were 3/30 (10 %) patients who were previously diagnosed with myocardial infarction.

Troponin levels of all patients were significantly elevated with a median maximum troponin level 23,6 × ULN. None of the patients had atrial fibrillation/flutter or other types of supraventricular or ventricular tachycardia at presentation or during hospitalisation, neither was there a prior history of arrhythmia. Only 1 patient died during a mean follow-up of 5.5 years.

Computed tomography coronary angiography

The CTCA was performed within 3 days after ICA. A total number of 452 segments were analysed. All coronary artery segments were of diagnostic image quality. A total of 24 patients had normal coronary arteries, and 6 patients had coronary atherosclerosis. In the case of atherosclerosis, the median number of segments with plaque per patient was one. In total, 9 segments with non-obstructive plaque were identified in these 6 patients. Four patients showed plaque in just one segment, one patient showed plaque in 2 segments and one patient had plaque in three coronary segments. Two plaques were classified as non-calcified, five plaques as calcified and two plaques were mixed.

Echocardiography subgroup

In 4/22 patients echocardiography was normal including normal global longitudinal strain (GLS) and normal wall motion score index (WMSI). 4/22 patients had normal GLS with pathological WMSI. 3/22 patients had pathological GLS and normal WMSI. 11/22 patients had pathological GLS and WMSI and among them we could identify 5 patients with Takotsubo pattern on echo (i.e. extensive area of mostly apical hypokinesia but not limited to the coronary artery perfusion territories). Mean ejection fraction (EF) was 55.9 ± 8.8 %, mean GLS-14.9 ± 3.2 % and WMSI 1.2 ± 0.24.

Among the 5 patients with only the echocardiography report available, 4 patients had normal systolic function with no wall motion abnormalities (WMA) and 1 patient had apical hypokinesia with normal systolic function.

Possible diagnosis

Based on the results of CTCA and echocardiography, the 22 patients with echocardiographic images available were grouped according to different possible diagnoses (Table 2).

The 6 patients who had coronary plaque on CTCA (Nr 1-6 in Table 2) were regarded as having a possible myocardial infarction due to plaque rupture. Mean EF in this group was 55.3 ± 9.8 %, mean GLS −16.0 ± 3.1 and mean WMSI 1.2 ± 0.3. Median maximum troponin level was 82 (12–101) × ULN.

Five patients without any plaques on CTCA had possible Takotsubo cardiomyopathy with the typical spatial distribution on echocardiography (Nr 7-11 in Table 2). The motion pattern of the left ventricular wall characteristic of Takotsubo cardiomyopathy is shown in the echocardiography of patient Nr 9 (see Additional files 1 and 2). In this group the mean EF was 54.0 ± 12.7 %, mean GLS −11.9 ± 3.0 and mean WMSI 1.5 ± 0,2. Median maximum troponin level was 119 (52–176) × ULN.

Six patients with no plaques on CTCA but with WMA on echocardiography (Nr 12-17 in Table 2) could have had a myocardial infarction due to a mechanism not involving plaque rupture (i.e. coronary dissection, embolism and vasospasm) or may not have had a myocardial infarction at all but myocarditis. An additional movie file shows the echocardiography of patient Nr 14 with suspected myocarditis (see Additional files 3 and 4). This group had a mean EF 58.0 ± 6.6 %, mean GLS −15.2 ± 2.5 and mean WMSI 1.2 ± 0.1. Median maximum troponin level was 19 (12–23) × ULN.

Five patients showed no plaque on CTCA and no WMA either (Nr 18-22 in Table 2). In this group the diagnosis is more uncertain. Some possible explanations could be a mild myocarditis with maintained wall motion, pulmonary embolism or undiagnosed paroxysmal tachycardia. In this group the mean EF was 54.2 ± 7.6 % and mean GLS −16.1 ± 2.8. WMSI was 1 in all 5 patients. Median maximum troponin level was 17 (4–21) × ULN.

Pharmacological treatment

At the time of discharge from the hospital the majority of patients, 28/30 (93 %) had been treated with acetyl salicylic acid, 28/30 (93 %) with statin, 25/30 (83 %) with beta-blocker and 22/30 (73 %) with clopidogrel. Half of the patients were discharged with angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitor (ACEI) or angiotensin receptor blocker (ARB). At the time of admission only a small percentage of patients, 9/30 (30 %) had any medication. In particular, 4 patients (13 %) were treated with acetylsalicylic acid, 5 patients (17 %) with beta blocker, 4 patients (13 %) with statin, 2 patients (7 %) with ACEI or ARB and 1 patient (3 %) with clopidogrel, calcium antagonist or diuretics.

Discussion

Contrary to our hypothesis and previous study findings [19], we found that the majority of our patients (80 %), who were diagnosed with AMI and lacked visible atherosclerosis on a routine invasive coronary angiography, had totally normal coronary arteries on CTCA as well. The remaining 20 % had only minimal, one-segment, non-obstructive atherosclerosis. The absence of atherosclerosis in the large majority of patients and the limited extent of atherosclerosis found in the remaining minority might suggest that other diagnoses than acute myocardial infarction are likely for most patients in this population. Echocardiography was available in a subgroup of patients and is known to provide sensitive and objective parameters for left ventricle systolic function such as GLS and WMSI that may help in arriving at a proper diagnosis. The addition of echocardiography to the CTCA findings enabled a probable diagnosis in the majority of the patients (17/22 in the echocardiography subgroup). For example, patients with atherosclerosis on CTCA and WMA on echocardiography could likely have had an acute myocardial infarction (based on plaque rupture) in the absence of other alternative explanations for their symptoms and elevated troponin. Echocardiography can additionally identify cases of Takotsubo cardiomyopathy (5/22 in the echocardiography subgroup). Abnormal echocardiography without any coronary atherosclerosis on CTCA indicates either myocarditis or myocardial infarction with a mechanism different from plaque rupture. In case of normal findings on CTCA and echocardiography, other factors such as mild myocarditis, arrhythmia, pulmonary embolism or renal failure (exclusion criterion in this study) seems more likely to explain the elevated troponins. Most patients in the study were prescribed acetylsalicylic acid and a great proportion of them were sent home with dual antiplatelet therapy, beta-blocker and statin, thus being treated as “classical” AMI patients. We do know however, that patients with AMI and insignificant coronary atherosclerosis have a lower incidence of adverse outcomes compared with patients with significant coronary artery disease [26]. Since these patients have a lower burden of risk factors, such extensive medication may seem inappropriate and potentially harmful.

When comparing with previous studies we found that the mean age of our study population, which was 60.2 years is in accordance with previously observed age for most first time AMI [27, 28]. The prevalence of risk factors was lower from what was observed in large epidemiological studies where the prevalence of diabetes, hypertension and hyperlipidemia was 18.5 %, 39.0 % and 90 % respectively [29]. In our small study the prevalence was 0 % for diabetes, 23 % for hypertension and 17 % for hyperlipidemia supporting a non-atherosclerotic etiology or a non AMI diagnosis in the majority. Most patients were women, 77 %, (23/30), which is in accordance with previous analyses where female gender was the strongest predictor of insignificant CAD in patients with NSTEMI [26]. The most frequent cause of AMI in similar female populations with non-obstructive CAD was previously found to be plaque rupture and ulceration [30]. The small percentage of patients having non-obstructive plaques on CTCA in our study compared with other studies [19, 20] is probably due to the more stringent criteria for inclusion requiring a totally normal angiogram whereas in previous studies patients with non-obstructive atherosclerosis up to 30–50 % on ICA were included. This study shows that if a normal coronary angiogram is found after a diagnosis of AMI, the CTCA will most probably also be normal or show only minimal atherosclerosis.

The theory of rupture of a non-obstructive plaque as an explanation for this population’s clinical presentation does not seem justified in 80 % of our population which had no signs of atherosclerosis at all (either on ICA or on CTCA). This fact leaves mechanisms like vasospasm, dissection, embolism and impaired coagulation and fibrinolysis more likely to be part of the pathogenesis of AMI. Non AMI diagnoses such as myocarditis, Takotsubo cardiomyopathy, pulmonary embolism and arrhythmias are also possible causes for this type of presentation. It is reasonable to consider using an intravascular imaging method [optical coherence tomography (OCT) or IVUS] to provide information about some mechanisms of coronary damage (i.e. plaque rupture, dissection or ulceration) in the case of AMI without coronary atherosclerosis but with wall motion abnormalities suggesting myocardial injury in a coronary artery territory or angiographic evidence of plaque rupture or impaired flow. Even if these patients fulfilled current diagnostic criteria for myocardial infarction, alternative explanations for chest pain and positive biomarkers may have been overlooked. In this clinical situation with leaking biomarkers and a normal coronary angiogram, cardiac MRI is of great importance for a definite diagnosis as it can differentiate between AMI, myocarditis and Takotsubo cardiomyopathy. It has been shown earlier that up to 50 % of patients with elevated troponin and unobstructed coronary arteries had myocarditis as diagnosed by cardiac MRI [31]. In another recent study [20] where 152 patients with MINCA underwent cardiac MRI, the findings were normal in two thirds of the patients, 7 % had signs of myocarditis and about 20 % signs of myocardial necrosis. Amongst patients with normal MRI, 32 % had typical clinical signs and symptoms of Takotsubo cardiomyopathy and reversible wall motion abnormalities. Interestingly, the initial diagnosis of AMI was changed in two thirds of the patients after the MRI examination. These findings suggest that a significant part of this population actually has other diagnoses than AMI and more extensive evaluation than just coronary angiography is needed.

Clinical implications

It is known that the diagnosis of acute myocardial infarction can have important implications for patient and family in terms of psychological well-being [32, 33], health insurance, choice of future profession and professional licenses (e.g. driving or pilot). There are also implications for the society related to sick leave, pension-and insurance claims [34], diagnosis coding, health statistics and health system reimbursements.

All these personal and societal implications as well as the extensive secondary prevention commonly prescribed after a myocardial infarction, imply the need for correct diagnosis and suggest the use of advanced imaging modalities such as MRI, OCT and IVUS in patients presenting as having AMI but with no or minimal coronary atherosclerosis.

Study limitations

A limitation of the study is that echocardiography was not part of the study protocol and it was left to the treating physician to decide if an echocardiographic examination was necessary and when to perform it. Though we finally had access to echocardiography in the majority of patients, the content of the examinations and the parameter analysis was not predefined. Another limitation of the study is the low inclusion rate which raises thoughts that we may have had selection bias in the inclusion phase.

Conclusions

Despite a diagnosis of AMI, based on ESC guidelines criteria, the majority of patients with a completely normal ICA showed no coronary plaques on CTCA. A few patients had only minimal non-obstructive atherosclerosis. Our data suggest that most patients either had AMI caused by a mechanism not involving plaque rupture or had other possible diagnoses that were overlooked. Bearing in mind what consequences a diagnosis of AMI confers to the patient it is reasonable to extend the diagnostic evaluation of these patients to cardiac MRI for excluding myocarditis and/or intravascular imaging (OCT or IVUS) to provide information about some mechanisms of coronary damage.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The study complies with the Declaration of Helsinki. Approval was obtained from the Regional Ethical Review Board in Linköping (Dnr M72-08). All participants gave written informed consent to participate.

Consent for publication

All participants gave written informed consent for publication of individual clinical data.

Availability of data and materials

Due to statutory provisions regarding data- and privacy protection, the dataset supporting the conclusions of this article is available upon individual request directed to the corresponding author.

Abbreviations

- ACEI:

-

angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitor

- ACS:

-

acute coronary syndrome

- AMI:

-

acute myocardial infarction

- ARB:

-

angiotensin receptor blocker

- CAD:

-

coronary artery disease

- CTCA:

-

computed tomography coronary angiography

- EF:

-

ejection fraction

- GLS:

-

global longitudinal strain

- ICA:

-

invasive coronary angiography

- IVUS:

-

intravascular ultrasound

- LBBB:

-

left bundle branch block

- MINCA:

-

myocardial infarction with normal coronary arteries

- MRI:

-

magnetic resonance imaging

- NSTEMI:

-

non ST-elevation myocardial infarction

- OCT:

-

optical coherence tomography

- PCI:

-

percutaneous coronary intervention

- RBBB:

-

right bundle branch block

- STEMI:

-

ST-elevation myocardial infarction

- ULN:

-

upper limit of normal

- WMA:

-

wall motion abnormalities

- WMSI:

-

wall motion score index

References

Larsen AI, Galbraith PD, Ghali WA, Norris CM, Graham MM, Knudtson ML, et al. Characteristics and outcomes of patients with acute myocardial infarction and angiographically normal coronary arteries. Am J Cardiol. 2005;95(2):261–3.

Bugiardini R, Manfrini O, De Ferrari GM. Unanswered questions for management of acute coronary syndrome: risk stratification of patients with minimal disease or normal findings on coronary angiography. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166(13):1391–5.

Sztajzel J, Mach F, Righetti A. Role of the vascular endothelium in patients with angina pectoris or acute myocardial infarction with normal coronary arteries. Postgrad Med J. 2000;76(891):16–21.

Dacosta A, Tardy-Poncet B, Isaaz K, Cerisier A, Mismetti P, Simitsidis S, et al. Prevalence of factor V Leiden (APCR) and other inherited thrombophilias in young patients with myocardial infarction and normal coronary arteries. Heart. 1998;80(4):338–40.

Glagov S, Weisenberg E, Zarins CK, Stankunavicius R, Kolettis GJ. Compensatory enlargement of human atherosclerotic coronary arteries. N Engl J Med. 1987;316(22):1371–5. doi:10.1056/NEJM198705283162204.

Libby P, Theroux P. Pathophysiology of coronary artery disease. Circulation. 2005;111(25):3481–8.

Kamineni R, Sadhu A, Alpert JS. Spontaneous coronary artery dissection: report of two cases and a 50-year review of the literature. Cardiol Rev. 2002;10(5):279–84. doi:10.1097/01.CRD.0000028805.70473.72.

Prizel KR, Hutchins GM, Bulkley BH. Coronary artery embolism and myocardial infarction. Ann Intern Med. 1978;88(2):155–61.

Maseri A, L’Abbate A, Baroldi G, Chierchia S, Marzilli M, Ballestra AM, et al. Coronary vasospasm as a possible cause of myocardial infarction. A conclusion derived from the study of “preinfarction” angina. N Engl J Med. 1978;299(23):1271–7. doi:10.1056/NEJM197812072992303.

Benacerraf A, Scholl JM, Achard F, Tonnelier M, Lavergne G. Coronary spasm and thrombosis associated with myocardial infarction in a patient with nearly normal coronary arteries. Circulation. 1983;67(5):1147–50.

Ambrose JA, Tannenbaum MA, Alexopoulos D, Hjemdahl-Monsen CE, Leavy J, Weiss M, et al. Angiographic progression of coronary artery disease and the development of myocardial infarction. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1988;12(1):56–62.

Leber AW, Knez A, Von Ziegler F, Becker A, Nikolaou K, Paul S, et al. Quantification of obstructive and nonobstructive coronary lesions by 64-slice computed tomography: a comparative study with quantitative coronary angiography and intravascular ultrasound. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2005;46(1):147–54.

Nikolaou K, Knez A, Rist C, Wintersperger BJ, Leber A, Johnson T, et al. Accuracy of 64-MDCT in the diagnosis of ischemic heart disease. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2006;187(1):111–7.

Ehara M, Surmely JF, Kawai M, Katoh O, Matsubara T, Terashima M, et al. Diagnostic accuracy of 64-slice computed tomography for detecting angiographically significant coronary artery stenosis in an unselected consecutive patient population: comparison with conventional invasive angiography. Circ J. 2006;70(5):564–71.

Raff GL, Gallagher MJ, O’Neill WW, Goldstein JA. Diagnostic accuracy of noninvasive coronary angiography using 64-slice spiral computed tomography. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2005;46(3):552–7.

Schroeder S, Kopp AF, Baumbach A, Meisner C, Kuettner A, Georg C, et al. Noninvasive detection and evaluation of atherosclerotic coronary plaques with multislice computed tomography. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2001;37(5):1430–5.

Komatsu S, Hirayama A, Omori Y, Ueda Y, Mizote I, Fujisawa Y, et al. Detection of coronary plaque by computed tomography with a novel plaque analysis system, ‘Plaque Map’, and comparison with intravascular ultrasound and angioscopy. Circ J. 2005;69(1):72–7.

Kopp AF, Schroeder S, Baumbach A, Kuettner A, Georg C, Ohnesorge B, et al. Non-invasive characterisation of coronary lesion morphology and composition by multislice CT: first results in comparison with intracoronary ultrasound. Eur Radiol. 2001;11(9):1607–11.

Aldrovandi A, Cademartiri F, Arduini D, Lina D, Ugo F, Maffei E, et al. Computed tomography coronary angiography in patients with acute myocardial infarction without significant coronary stenosis. Circulation. 2012;126(25):3000–7. doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.112.117598.

Collste O, Sorensson P, Frick M, Agewall S, Daniel M, Henareh L, et al. Myocardial infarction with normal coronary arteries is common and associated with normal findings on cardiovascular magnetic resonance imaging: results from the Stockholm Myocardial Infarction with Normal Coronaries study. J Intern Med. 2013;273(2):189–96. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2796.2012.02567.x.

Thygesen K, Alpert JS, White HD. Joint ESCAAHAWHFTFftRoMI. Universal definition of myocardial infarction. Eur Heart J. 2007;28(20):2525–38. doi:10.1093/eurheartj/ehm355.

Boogers MJ, Schuijf JD, Kitslaar PH, Van Werkhoven JM, De Graaf FR, Boersma E, et al. Automated quantification of stenosis severity on 64-slice CT: a comparison with quantitative coronary angiography. J Am Coll Cardiol Img. 2010;3(7):699–709. doi:10.1016/j.jcmg.2010.01.010.

Leber AW, Knez A, Becker A, Becker C, Von Ziegler F, Nikolaou K, et al. Accuracy of multidetector spiral computed tomography in identifying and differentiating the composition of coronary atherosclerotic plaques: a comparative study with intracoronary ultrasound. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2004;43(7):1241–7. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2003.10.059.

Austen WG, Edwards JE, Frye RL, Gensini GG, Gott VL, Griffith LS, et al. A reporting system on patients evaluated for coronary artery disease. Report of the Ad Hoc Committee for Grading of Coronary Artery Disease, Council on Cardiovascular Surgery, American Heart Association. Circulation. 1975;51(4 Suppl):5–40.

Van Velzen JE, Schuijf JD, De Graaf FR, Boersma E, Pundziute G, Spano F, et al. Diagnostic performance of non-invasive multidetector computed tomography coronary angiography to detect coronary artery disease using different endpoints: detection of significant stenosis vs. detection of atherosclerosis. Eur Heart J. 2011;32(5):637–45. doi:10.1093/eurheartj/ehq395.

Patel MR, Chen AY, Peterson ED, Newby LK, Pollack Jr CV, Brindis RG, et al. Prevalence, predictors, and outcomes of patients with non-ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction and insignificant coronary artery disease: results from the Can Rapid risk stratification of Unstable angina patients Suppress ADverse outcomes with Early implementation of the ACC/AHA Guidelines (CRUSADE) initiative. Am Heart J. 2006;152(4):641–7. doi:10.1016/j.ahj.2006.02.035.

Anand SS, Islam S, Rosengren A, Franzosi MG, Steyn K, Yusufali AH, et al. Risk factors for myocardial infarction in women and men: insights from the INTERHEART study. Eur Heart J. 2008;29(7):932–40. doi:10.1093/eurheartj/ehn018.

Bahler C, Gutzwiller F, Erne P, Radovanovic D. Lower age at first myocardial infarction in female compared to male smokers. Eur J Prev Cardiol. 2012;19(5):1184–93. doi:10.1177/1741826711422764.

Yusuf S, Hawken S, Ounpuu S, Dans T, Avezum A, Lanas F, et al. Effect of potentially modifiable risk factors associated with myocardial infarction in 52 countries (the INTERHEART study): case-control study. Lancet. 2004;364(9438):937–52. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(04)17018-9.

Reynolds HR, Srichai MB, Iqbal SN, Slater JN, Mancini GB, Feit F, et al. Mechanisms of myocardial infarction in women without angiographically obstructive coronary artery disease. Circulation. 2011;124(13):1414–25. doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.111.026542.

Assomull RG, Lyne JC, Keenan N, Gulati A, Bunce NH, Davies SW, et al. The role of cardiovascular magnetic resonance in patients presenting with chest pain, raised troponin, and unobstructed coronary arteries. Eur Heart J. 2007;28(10):1242–9. doi:10.1093/eurheartj/ehm113.

Kristofferzon ML, Lofmark R, Carlsson M. Managing consequences and finding hope--experiences of Swedish women and men 4-6 months after myocardial infarction. Scand J Caring Sci. 2008;22(3):367–75. doi:10.1111/j.1471-6712.2007.00538.x.

Fosbol EL, Peterson ED, Weeke P, Wang TY, Mathews R, Kober L, et al. Spousal depression, anxiety, and suicide after myocardial infarction. Eur Heart J. 2013;34(9):649–56. doi:10.1093/eurheartj/ehs242.

Masini V. Psychological and occupational repercussions of myocardial infarct. G Ital Cardiol. 1979;9(8):889–90.

Acknowledgements

The authors are thankful to all their colleagues and medical staff of their institutions for their great contribution to the implementation of this study.

Funding

This research was partly funded by the Swedish Heart and Lung Foundation (grant no 20120449), the Region of Östergötland (grant no 437491), the European Union FP 7 (grant no 223615) and the Medical Research Council of Southeast Sweden (grant no 157921).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

ES is responsible for the conception and design of the study together with JA, JC, JEK, ASP and JE who also evaluated the echocardiograms. GP analyzed and interpreted the data and drafted the manuscript. WGW helped to draft the manuscript and together with GaP analyzed and interpreted the CTCA data. All authors critically revised the manuscript and added important intellectual content. All authors have read and approved the manuscript.

Additional files

Pat 9 - 4 chamber view. (MPG 1026 kb)

Additional file 2:

Pat 9 - 2 chamber view. (MPG 1272 kb)

Pat 14 - 4 chamber view. (MPG 736 kb)

Pat 14 - 4 chamber view, still frame. (BMP 3338 kb)

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Panayi, G., Wieringa, W.G., Alfredsson, J. et al. Computed tomography coronary angiography in patients with acute myocardial infarction and normal invasive coronary angiography. BMC Cardiovasc Disord 16, 78 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12872-016-0254-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12872-016-0254-y