Abstract

Background

It is critical to study the low nitrogen tolerance in wild soybean with extensive genetic diversity for improving cultivated soybean nitrogen use efficiency. Focusing on plant young and old leaves could provide new insights to low nitrogen tolerance research. This study compared the low nitrogen group with the control group on physiological and metabolomics changes in young and old leaves, respectively, then analyzed and compared the differences of these changes between cultivated and wild soybean. This study aimed to provide a theoretical basis for the molecular mechanism of soybean low nitrogen stress tolerance.

Results

Wild soybean was less affected by low-nitrogen stress than cultivated soybean as assessed by plant biomass paraments, total carbon content and total nitrogen content. Gas-exchange coefficients and chlorophylls contents maintained relatively stable in wild soybean young leaves, but opposite in cultivated soybean. Wild soybean young leaves also increased the transport of beneficial ions, such as B3+, Fe3+, Mn2+, H2PO4− and C2O42−. In wild soybean old leaves, the nitrogen metabolism pathway was significant enhanced, especially the aspartic acid and GABA metabolisms. While in cultivated soybean, the nitrogen metabolism decreased obviously in young leaves but had no significant change in old leaves. The phenylpropanoid metabolism pathway was also activated in wild soybean. Contrary to cultivated soybeans, wild soybean tricarboxylic acid cycle and carbon metabolism including polyols and organic acids consolidated in old leaves and maintained a relative normal state in young leaves. These strategies could improve the antioxidant and N-fixation capacity in wild soybean.

Conclusion

The survival and growth of wild soybean under low nitrogen stress conditions relied on physiological adjustments and metabolic changes that occurred at the cellular level. Compared with cultivated soybean, wild soybean young leaves could maintain a relatively normal growth mainly owing to a significant enhancement of key amino acids and nonprotein nitrogen metabolism in old leaves, especially aspartic acid, proline metabolism which provided basis for nitrogen reutilization from old leaves to young leaves. Consolidating the tricarboxylic acid cycle, intensifying phenylpropanoid metabolism, and accumulating more polyols and organic acids also had positive effect on it.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Nitrogen (N) is an essential nutritional element and its availability is extremely correlated with crop growth, yields and stress-responses [1]. Excess N compounds released from agricultural systems threaten the quality of air, water, and soil, which is also currently costing the European Union between €70 billion and €320 billion per year [2]. Improving plant N use efficiency is a significant challenge. Wild soybean (W, Glycine soja) is an important germplasm resource for studying stress resistance [3]. Wild soybean survives in natural selection and has unique physiological mechanisms for adapting to abiotic stress compared with cultivated soybean (C, Glycine max) [4]. It is critical to study low nitrogen (LN) tolerance strategy in wild soybeans with extensive genetic diversity for improving cultivated soybean N use efficiency.

Redistributions of ions and organic matters among different organs is essential for plant activities [5]. Many aspects of cellular metabolism have a direct impact on N metabolism activity in tissues, which is established through the combination of many genes, chemical balance and multi-layer regulation [6]. Nowadays, more and more researchers pay attention to the nitrogenous compounds reutilization under the stress conditions, especially low nitrogen condition [7]. Growth and physiological parameters at the seedling stage can be measured to determine abiotic stress-tolerance levels [8]. Metabolomics lends insight into the deep relationship between metabolites and changes in plant physiology conditions by combining a range of different analytical technologies and calculation methods [9]. In recent years, ionomics and metabolomics analyses have been widely used to determine responses to various abiotic stresses, including salinity, drought and nutritional deficits [10,11,12].

Numerous nutrient- and metabolic-based disorders, assessed in plant leaves and root, have been recorded under abiotic stress conditions [13]. While, the most studies used multiple leaf pools, giving no consideration to different positions and ages of the leaves. During the leaf growth, old leaf represent the final stage of leaf development and is characterized by the transition from nutrient assimilation to nutrient remobilization [14]. Plant Phloem-mobile nutrients redistribution is highly important for the economical use of nutrients under the stress [15]. The amino acids exported from old leaves may be utilized for the synthesis of constituents (e.g. enzyme, regulatory, or mem-brane proteins, nucleotides, and chlorophyll) in developing young leaves [16]. In Arabidopsis, phloem loading of nitrate in the source leaf and nitrate transport out of old leaves and into young leaves were rely on nitrate transporter NRT1.7 [17]. Meanwhile, a new study identified a genetic mechanism by young and old leaves differentially control stress-response cross-talk, this mechanism balances stress-response trade-offs to maintain plant growth and reproduction during stress [18]. Studies about the changes of metabolic processes include photosynthesis, respiration, nitrogen metabolism, sugar metabolism and fatty acid synthesis in young and mature leaves indicated that young and old leaves play different roles in response to abiotic stress conditions [19,20,21]. Therefore, focusing on plant young and old leaves could provide new insights to low nitrogen tolerance research.

To reveal the tolerant strategies in wild soybean to LN stress, the two experimental materials, W and C were subjected to low nitrogen treatment, and then the physiological and metabolite changes were compared between low nitrogen group and control group (CK) in the two soybean genotypes young and old leaves, respectively. Subsequently, we analyzed and compared the differences of these changes between cultivated soybean and wild soybean. Aim to provide a theoretical basis for the molecular mechanism of W tolerance to LN stress and the complex metabolic regulatory network involved in plant LN tolerance.

Results

Growth and photosynthetic characteristics

The LN stress had various significant effects on the two soybean genotypes performance. The biomass results showed C shoot height, root length, fresh weight and dry weight had a more significant inhibition than W (Additional file 1). Compared with CK, C young leaves total carbon content (%) decreased 11% significantly and total nitrogen content (%) decreased 10% significantly under the LN condition (P < 0.05); Under the same condition, W young leaves total carbon content (%) and total nitrogen content (%) had no significant changes (P > 0.05); C old leaves total carbon content (%) and total nitrogen content (%) had no significant changes (P > 0.05); W old leaves total nitrogen content (%) decreased significantly (P < 0.05) and total carbon content (%) had no significant changes (P > 0.05) (Table 1).

In C young leaves, compared with CK, the leaf net photosynthetic rate (PN), stomatal conductance (gs) and transportation rate (E) decreased significantly by 61, 55 and 30%, respectively (P < 0.05). In W young leaves, PN decreased less than in C young leaves, meanwhile gs, E and ratio of sub-stomatal to atmospheric CO2 concentrations (Ci /Ca) were increased, compared with CK. In the old leaves of both two genotypes, compared with CK, PN, gs and E decreased under the LN stress, especially in C, that the PN, gs and E values decreased by 66, 71 and 49%, respectively. Compared with CK, Ci/Ca increased significantly under LN-stress conditions in W (Fig. 1). Compared with CK, Chl a, Chl b, Chl (a + b) and Car contents were all decreased in both C and W young leaves. The chlorophylls deceased more in C young leaves than in W young leaves. The similar trend also occurs in the old leaves of W and C. Compared with CK, Chl a, Chl b and Chl (a + b) contents decreased in W and C significantly (P < 0.05), especially in C old leaves. Car content was increased in W old leaves (Fig. 1).

The changes in photosynthetic characteristics of the two soybean genotypes under CK and LN stress. (a) young leaves net photosynthetic rate (PN); (b) young leaves stomatal conductance (gs); (c) young leaves transpiration rate (E); (d) young leaves ratio of sub-stomatal to atmospheric CO2 concentrations (Ci/Ca); (e) young leaves chlorophyll a (Chl a); (f) young leaves chlorophyll b (Chl b); (g) young leaves chlorophyll a + chlorophyll b (Chl (a + b)); (h) young leaves carotenoid (Car); (i) old leaves net photosynthetic rate (PN); (g) old leaves stomatal conductance (gs); (k) old leaves transpiration rate (E); (l) old leaves ratio of sub-stomatal to atmospheric CO2 concentrations (Ci/Ca); (m) old leaves chlorophyll a (Chl a); (n) old leaves chlorophyll b (Chl b); (o) old leaves chlorophyll a + chlorophyll b (Chl (a + b)); (p) old leaves carotenoid (Car); C, cultivar soybean; W, wild soybean. CK, control treatment; LN, low-nitrogen stress; Error bars indicate the standard error (n = 4); * and ** indicate significant (P < 0.05) and highly significant (P < 0.01) differences, respectively

Ionomics responses

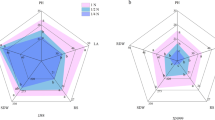

According to the principal component analysis (PCA) of the ion contents in the two soybean genotypes young and old leaves, there were obvious differences in ionomics under LN-stress conditions (Fig. 2a). The young and old leaves were clearly separated by the first component (PC1), representing 37.8% of the total variation, and P5+, K+, Mg2+, Ca2+ and NO3− were the major contributors. PC2 distinguished the control and LN stress groups, which represented 31.9% of the variation, and SO42−, NO3−, H2PO4− and P5+ were major contributors to PC2 (Fig. 2b; Additional file 2). In response to LN stress, compared with the CK, the contents of NO3−, Na+ and Mg2+ declined in the young leaves of the two soybean genotypes, especially in C, in which they significantly decreased by 54, 45 and 17%, respectively (P < 0.05). The contents of H2PO4−, C2O42−, Mn2+, B3+, Fe3+, K+ and P5+ increased significantly in W young leaves (P < 0.05). In the old leaves, Ca2+, Mg2+ and NO3− contents decreased in W and C. The contents of H2PO4−, SO42−, Na+, B3+, Fe3+ and Zn2+ increased significantly in W old leaves (P < 0.05) (Table 2).

Metabolomics analysis

We conducted a PCA on the detected differential metabolites to identify the key factors affecting the metabolomics (Fig. 3; Additional file 3). PC1 explained 81.2% of the variance in young leaves and 78% of the variance in old leaves, which predominantly reflected the difference between W and C; PC2 distinguished the CK and LN-stress groups that explained 10.7% of the variance in young leaves and 9.6% of the variance in old leaves, indicating that LN stress had a substantive effect on the metabolites (Fig. 3a;b). The contribution of metabolites in young leaves to PC1 was dominated by fumaric acid, alanine, serine, myo-inositol and glucose-6-phosphate, while ethanolamine, asparagine, serine, valine and fumaric acid were major contributors to PC2 (Fig. 3c; Additional file 4). The contributions of metabolites in old leaves to PC1 came several metabolites, dominated by monopalmitin, fumaric acid myo-inositol, sucrose, valine and butyrate, while caffeic acid monopalmitin and valine were the dominate metabolites contributing to PC2 (Fig. 3d; Additional file 5).

The levels of 54 differential metabolites of young leaves in W and C were independently calculated and compared (Table 3; Fig. 4a). In the young leaves, the content of the tricarboxylic acid (TCA) cycle intermediate succinic acid was increased in W but declined in C, while that of L-malic acid decreased in both soybean genotypes, but especially in C. The metabolites related to glycolysis, including fructose-6-phosphate, glyceric acid and pyruvic acid, decreased significantly in C young leaves (P < 0.05). However, in W young leaves, the levels of glucose-6-phosphate and pyruvic acid decreased, while those of fructose-6-phosphate and glyceric acid increased.

Changes in the metabolic pathways of young and old leaves in the two soybean genotypes. Suggested changes in the metabolic network in soybean seedlings under LN-stress conditions based on a partial least square-discriminant analysis (PLS-DA). (a) pathway of young leaves; (b) pathway of old leaves. C, cultivar soybean; W, wild soybean; CK, control treatment; LN, low-nitrogen stress

The contents of differential amino acids, including the aliphatic amino acids isoleucine, aspartic acid, asparagine, L-homoserine, L-threonine, serine, proline, alanine, glycine and glutamate, and the aromatic amino acids tyrosine and phenylalanine, significantly decreased in C young leaves during LN stress compared with the CK (P < 0.05). The non-protein N, such as ethanolamine, monoamine and sphingosine, had the same trend. Under the same treatment, L-threonine, alanine, glycine, ethanolamine (aliphatic amino acid) and sphingosine (nonprotein N) levels increased in W young leaves, while the other amino acids and non-protein N decreased in W young leaves. However, the ranges of the decreases were less than those in C. In C young leaves, the contents of polyols, like threitol, galactinol, glycerol, myo-inositol and L-threose (monosaccharide), decreased significantly (P < 0.05), while the contents of xylose (monosaccharide), sucrose, maltose (disaccharides), maltotriose and melezitose (trisaccharide) increased. The polyols and carbohydrate metabolites did not significantly change in W (P > 0.05). In W young leaves, the levels of organic acids, including itaconic, methylmalonic, maleic, gluconic and nicotinic acids, increased in response to LN stress. The contents of threonic acid, galactonic acid, glucoheptonic acid, 4-hydroxybutyrate, hydroxypropionic acid and oxalic acid decreased in both soybean genotype, but 4-hydroxybutyrate, hydroxypropionic acid and oxalic acid decreased more significantly in C young leaves (P < 0.05). The levels of the stearic, palmitic, linolenic and linoleic fatty acids decreased in both soybean genotypes, but especially in C young leaves. The contents of phenylpropanoids, including salicylic acid, prunin and ferulic acid, increased in W young leaves, while the opposite trend occurred in C young leaves. Neohesperidin and caffeic acid levels decreased in the young leaves of both soybean genotypes.

In the old leaves of W and C, the levels of 64 metabolites were independently calculated and compared (Table 4; Fig. 4b). In W old leaves, the intermediates of the TCA cycle, including fumaric, malic, citramalic, succinic and succinic acids, increased, while the opposite trend occurred in C old leaves. The contents of glycolysis-related metabolites increased in W old leaves. Compared with the CK, the levels of galactose, fructose-6-phosphate, glucose-6-phosphate, lactic acid and galactonic acid increased but those of glyceric and pyruvic acids decreased in C old leaves. The amino acids contents all increased in W old leaves under LN-stress conditions but did not significantly change in C old leaves (P > 0.05). The contents of non-protein N in W old leaves also increased, while 4-aminobutyric acid and maleimide decreased in C. The contents of polyols, including monopalmitin, myo-inositol, palatinitol, arabitol, threitol and erythritol, increased in the old leaves of both soybean genotypes, but especially in W. Sucrose decreased in the both genotypes old leaves, while maltose, melezitose, L-threose and fucose levels increased in W old leaves under LN-stress conditions. The contents of organic acids, including ketoisocaproic, 2-deoxytetronic, oxalic, propionic, gluconic and glucoheptonic acids, increased in W and C old leaves, but the increase was more significant in the former. The contents of butyrate and maleic acid decreased in C old leaves and increased in those of W. Among the fatty acids, stearic, linoleic, palmitic, linolenic and isobutyric acid contents increased, while that of butyric acid decreased, in both soybean genotypes’ old leaves. The contents of neohesperidin, salicylic acid, trans-cinnamate acid and naringin increased significantly in W and C old leaves (P < 0.05), while the contents of ferulic acid and caffeic acid increased in C old leaves but declined in W old leaves.

Discussion

LN stress can retard plant development [22, 23]. Our biomass results largely confirmed previously reports in which W had a greater LN tolerance [24]. We then distinguished different responses between young and old leaves under LN-stress conditions, providing new insights into the strategies of W resistance to LN stress. The total carbon content (%) and total nitrogen content (%) result showed C had a worse carbon deficiency in C young leaves than W young leaves. While in W young leaves total carbon content (%) and total nitrogen content (%) maintained a relatively normal state, probable cause may be the transport of N from the old leaves, as the N content in the old leaves is significantly reduced [17]. Chlorophylls contents, as the nitrogen statue marker in leaves, decreased less in wild soybean young and old leaves than that in cultivated soybean. Chloroplast proteins proteolysis in senescence leaves and the liberated amino acids can be exported to growing parts of the plant [14]. The analyses of gas-exchange parameters and chlorophyll contents changes provide insights into the photosynthetic and nitrogen states of plants under different conditions [24]. Under LN-stress conditions, compared with CK, PN in W old and young leaves decreased less than that in C. The decrease in PN was evaluated in terms of non-stomatal factors, which include biochemical and structural processes [25, 26]. E in W young leaves increased under LN-stress conditions, and the increase in transpiration could promote the transport and transportation of ions [8]. There are balances and dependencies among the various elements in crops, and the lack of certain elements often affects the transport, accumulation and metabolism of other nutrients [27]. Compared with CK, the Fe3+, Mn2+ and H2PO4− contents in W young and old leaves increased significantly more than in C under LN-stress conditions, and the levels of these ions were positively correlated with N metabolism [28,29,30]. The increase of B in W young leaves under LN-stress conditions was much greater than that in C. The B3+ content could enhance photosynthesis and promote vascular bundle development in legumes; therefore, rhizobia could obtain sufficient carbohydrate supplies to enhance the N fixation capability [31]. The NO3− content decreased less in W than in C, and also decreased less in young leaves than in old leaves. This corroborates previous results in which NRT1.7 was indicated to regulate NO3− transport out of older leaves and into younger leaves [17]. Our study indicated that W young leaves could maintain a relatively stable gas-exchange coefficient, while W young and old leaves increased their transport and remobilization levels of beneficial ions, which is important to sustain vigorous growth during N deficiency.

Combining with the previous research, short-term relative LN treatment of this strength had no significant effect on soybean root nodules development [24]. Therefore, we considered that the response of two soybean genotypes to LN stress was mainly in the metabolic level. Carbon and nitrogen metabolism are tightly coupled in different living organisms, which is essential for every biological system, since all major cellular components, including genetic materials, proteins, pigments, energy carrier molecules, etc., are derived from these activities. Under stress conditions, different regulatory levels exist in cells to maintain the properly balanced metabolism ratio between carbon and N that is necessary to avoid metabolic inefficiencies [32, 33]. N may acted as the signal to initiate coordinated changes in carbon and N metabolisms and organic acid production [33]. Adverse growth conditions induce the accumulation of polyols. The function of polyols as “stress metabolites” and correlated expression patterns have been observed across environmental gradients [34]. During LN stress, compared with CK, there was less inhibition of sugar and polyol metabolism in W young leaves than in C. However, sugar and polyol metabolism in W old leaves increased insignificantly, especially polyol metabolism. Although hydroxyls produced by nitrate reduction decreased during LN stress, the frequency of electron carriers in the electron transport chain decreased, resulting in a significant increase in reactive oxygen species [34]. Polyols are major constituents of plant soluble components, and they are important substances involved in intracellular osmotic regulation and in enhancing resistance to reactive oxygen species [35]. Moreover, up to 30% of the gross primary production was thought to proceed through polyols in place of carbohydrates [36]. The enhancement of polyol metabolism, including the production of monopalmitin, myo-inositol, palatinitol, arabitol, threitol and erythritol, mainly occurred in W old leaves under LN-stress conditions. In contrast to carbohydrates, polyols lack aldehyde and ketone functional groups, making them well suited to transport entities and storage molecules [37]. Thus, they function to transport carbon skeletons and energy between source and sink organs [36]. The strategy of enhancing polyols metabolism and transport polyols from old leaves to young leaves could effectively improve the LN tolerance of W.

The results showed that saturated fatty acid and organic acid contents in W old leaves increased which may be also adaptive strategies of W under adversity [38]. Organic acid metabolism not only provides carbon skeletons during N assimilation but also has potential roles in osmotic regulation, cation balance, nutrient deficiency-related coping mechanisms and plant–microbe interactions at the root–soil interface [38]. Compared with CK, the organic acid metabolism, producing itaconic, gluconic and nicotinic acids, increased in W young leaves under the LN-stress conditions. Additionally, in W old leaves, the metabolisms of ketoisocaproic, 2-deoxytetronic, oxalic, propionic, gluconic and glucoheptonic acids showed the same trend. The accumulation of organic acids can improve soil acidity and increase the availability of rhizospheric soil [38]. Another probable significance of organic acid accumulation is their participation in balancing the charges formed during the extensive metabolism of anions, such as NO3− [39]. The rate of N uptake by soybean roots may increase when stimulated by organic acids [40].

Phenylpropanoid biosynthesis in plants engenders a vast variety of aromatic metabolites that are critical for their growth, development and environmental adaptability [41]. All phenylpropanoids, such as flavonoids, lignins and alkaloids, are derived from trans-cinnamic acid, which is formed from phenylalanine by the action of phenylalanine ammonia-lyase [42]. Here, the phenylpropanoid biosynthetic pathway was significantly active in W young and old leaves under LN-stress conditions. The increased metabolisms of phenylalanine and trans-cinnamic acid ensured an adequate supply of substrates to produced beneficial secondary metabolites. The positive correlation between flavonoid metabolic levels and antioxidant properties has been reported, and flavonoids can promote plant-microbe interactions and enhance root colonization by microbes [43, 44]. Moreover, salicylic acid may be part of the signaling process that results in systemic acquired resistance [45].

The metabolism of carbon and N also involves energy metabolism. Compared with CK, glycolysis in W young and old leaves was maintained at a relatively stable state under LN-stress conditions. In C old leaves, the first stage of glycolysis (energy-consuming process) was enhanced, but the second stage (energy-producing) was decreased. Prophase studies in functional leaves revealed that soybean has a glycolysis-enhancing strategy to adapt to abiotic stress [13]. Although enhanced glycolysis levels could compensate for lower ATP yields, limited energy would be generated owing to the incomplete oxidation of organic matter, and there was a risk of depleting the respiratory substrate, which is uneconomical for plant growth [46]. The TCA cycle is the most important source of energy for cells. In W young and old leaves, the TCA cycle is significantly enhanced, which ensured that W could maintain a relatively stable supply of material and energy metabolism, resulting in the production of a steady energy supply during LN stress. However, the opposite trend occurred in C, and the production of important TCA cycle intermediates, including succinic acid and malic acid, was significantly inhibited in C young leaves. However, half of the TCA cycle intermediates represent the origins of pathways leading to important metabolites, such as fatty acids, amino acids and porphyrins [47]. Therefore, the energy metabolism-related strategies of W young and old leaves had obvious advantages compared with those of C under LN-stress conditions.

Amino acid metabolism is of crucial importance in N metabolism because it influences plant cell behavior in a myriad of ways [48]. The metabolism of amino acids in W young leaves was relatively stable, but the metabolism of amino acids in C young leaves was significantly inhibited. In W old leaves, amino acid metabolism was significantly enhanced, while it showed no significant change in C old leaves. In addition to their roles as protein constituents, amino acids are also involved in plant growth and development, osmotic adjustment, anti-oxidation, intracellular pH control, metabolic energy production and resistance to both abiotic and biotic stresses [49]. The enhanced amino acids metabolism in W old leaves resulted in increased contents of nitrogenous compounds. This strategy might provide a material basis for nitrogen and nitrogen transport among old and young leaves. On the contrary, N metabolism in C old leaves underwent no significant change, but the amino acid contents were significantly decreased in C young leaves under LN-stress conditions, compared with the CK. This further confirmed that the LN resistance in C was correlated with the inadequate N transport and reutilization capacities from young to old leaves. Proline is a major organic osmolyte that accumulates in some plant species in response to environmental stresses [50]. Proline metabolism was enhanced in W old leaves, which improved the LN tolerance. The reverse regulation of the pathways that compete with amino acid synthesis in plants could balance the C and N metabolism in plants [49]. When the energy supply was sufficient, including the high light and high-concentration carbohydrate, GS and GOGAT cycle could be activated and will promote N assimilation into glutamic acid metabolism. On the contrary, GS and Fd-GOGAT were inhibited, while AS was activated, and N assimilation proceeded towards asparagine metabolism [51]. The reverse regulation of these competing pathways can balance Carbon and Nitrogen metabolism in plants [52, 53]. In plants, the aspartic acid metabolism is highly important because it culminates with the synthesis of several essential amino acids, such as L − homoserine, L − threonine, Alanine, lysine, threonine and isoleucine [54]. Asparagine plays a central role in N transport and storage in plants owing to its high N/carbon ratio and stability. In older leaves nitrogen is not required for growth, and previous studies have shown that transpirationally derived asparagine in older leaves is re-exported to the apex [54, 55]. W old leaves may have increased aspartic acid metabolism to maintain the stability and balance of N nutrition from old leaves to young leaves. GABA is involved in the temporary storage of N and can be an anaplerotic compound by providing TCA cycle intermediates during stress responses [56]. Additionally, metabolome and transcriptome studies indicate that GABA might play a role in coordinating the carbon–N balance and even mediate a starvation response in plant cells [57, 58]. The accumulation of GABA in W old leaves ensured efficient N reuse, which is an essential process to maintain the carbon and N balance [54]. Oxidative stress induced by abiotic stress enhances protein catabolism and results in increased amino acids levels [19, 59]. The current challenge is to elucidate the diverse mechanisms of amino acid enrichment.

Conclusion

The survival and growth of wild soybean under LN-stress conditions relied on physiological adjustments and metabolic changes in plant. Compared with cultivated soybean, wild soybean young leaves maintained relatively stable assimilative capacity and increased the cyclic utilization of beneficial ions. The relative normal growth of wild soybean young leaves under the low nitrogen condition mainly owing to a significant enhancement of nitrogen metabolism in old leaves, especially aspartic acid, proline and GABA metabolism. Therefore, the increased of key amino acids and nonprotein nitrogen provided a material basis for N storage, transportation and reutilization from old leaves to young leaves. Meanwhile, intensifying phenylpropanoid metabolic pathway in old young and old leaves had a positive effect in improving the low nitrogen resistance of wild soybean. Besides, consolidating the TCA cycle to ensure the energy supply, and accumulating more polyols and organic acids in old and young leaves, which not only alleviated the carbohydrate deficiency in developing young leaves, but also improved antioxidant and N fixation capacities. The results provide a foundation for further functional studies to explore metabolite regulation during abiotic-stress resistance in plants.

Methods

Plant materials and growth conditions

The experimental materials, seeds of wild soybean (W; ‘Huinan06116’) and cultivar soybean (C; ‘Jinong24’), were provided by Jilin Academy of Agriculture Science, China. The seedlings were grown arranged in 14-cm diameter pots with a bottom hole (2 cm in diameter) with clean sand. The seedlings were grown in an outdoor experimental field at Northeast Normal University, Changchun, Jilin. The average growth temperatures were 18.5 ± 1.5 °C and 26 ± 2 °C during the night and day, respectively, and the relative humidity was 60 ± 5%. The seedlings were germinated by irrigation with water.

Stress treatments

W and C were both randomly divided into two groups, with eight pots each: control and LN-treated. Four pots were used for measuring photosynthetic parameters and ion content, and the remaining four pots for metabolomics analyses in each group. The LN treatment was initiated when the seedlings’ third leaves had grown. In the LN-treated group, W and C seeds were placed in 1/4-strength modified Hoagland’s solution for two weeks, and CK was cultivated under normal conditions (1× Hoagland’s solution [24].

Photosynthetic indices measurements

Two weeks after the stress treatment, choosing the first two blade from the top and the first two blade from the bottom of the shooting as the young leaves and the old leaves in four pots receiving the same treatment in each pot. Three young and old leaves were selected in each pot, and three data points were recorded per leaf, for a total of 72 data points per parameter. The photosynthetic rate (PN), stomatal conductance (gs), intercellular CO2 concentration (Ci /Ca) and transpiration rate (E) values of leaves were determined using a LI-6400 portable open flow gas exchange system (LI-COR, USA) at 11:00 AM. The concentration of CO2 in the atmosphere, effective photosynthetic radiation, air temperature and humidity were 380 ± 5 cm3·m− 1, 1200 ± 50 μmol·m− 2·s− 1, 24 °C and 50%, respectively [60] .

Dry leaf samples (30 mg) were dipped into 10 ml of 80% acetone: anhydrous ethanol mixture (1:1) to extract the photosynthetic pigments in darkness at room temperature until the leaves became white. Each sample was repeated three times. Spectrophotometric (SpectrUV-754, Shanghai Accurate Scientific Instrument Co.) determinations at 440, 645 and 663 nm for each sample were performed three times using the formulae of Holm (1954).

Growth indices measurements

After the soybean plants were harvested, plant heights, root lengths, aboveground fresh weight (Up FW), underground FW (Under FW), aboveground dry weight (Up DW), and underground dry weight (Under DW) were measured [8].

Measurement of ion content

Dry 0.05 g samples were treated with 4 mL of deionized water at 100 °C for 40 min, and then centrifuged at 3000 g for 15 min, the supernatant was collected, and the course was repeated twice, with extracts made up to 15 mL. Unified supernatants were used to determine SO42−, NO3−, H2PO4−, Cl− and C2O42− concentrations by ion chromatography (DX-300 ion chromatographic system, AS4A-SC chromatographic column, CDM-II electrical conductivity detector, mobile phase: Na2CO3/NaHCO3 = 1.7/1.8 mM, Dionex, Sunnyvale, CA, USA). An atomic absorption spectrophotometer (Super 990F, Beijing Purkinje General Instrument Co. Ltd., Beijing, China) was used to determine the concentrations of Na+, K+, Ca2+, Mg2+, Fe3+, B3+, P5+, Zn2+ and Mn2+ [60].

Metabolite extraction and profiling analysis

Samples (50 mg) were transferred to 1.5 mL EP tubes (Eppendorf Micro Test Tubes, Eppendorf China Limited, Shanghai City, China), then added internal standard that consisted of 0.5 mL of extraction liquid (V (methanol): V (chloroform) = 3:1) and 60 μL of ribitol (0.2 mg mL − 1stock in H2O). Centrifuged the simples for 10 min at 12,000 g, at 4 °C (Tabletop Low-Speed Centrifuge L-500, Hunan Saite Xiangyi Centrifuge Instrument Co., Ltd., Hunan City, China), Then mixing thoroughly. 0.4 mL of the supernatant was transferred into a 2 mL GC-MS glass vial as a new sample. Exactly 80 μL of methoxyamination reagent (20 mg mL− 1 methoxylamine hydrochloride in pyridine) was added to the new samples. Then vortexed them for 10 s, dried in a vacuum concentrator, and placed in an oven (MKX-J1–10, Qingdao Makewave Microwave Technology Co. Ltd., Qingdao, China) adjusted to 37 °C for 2 h. Finally, 0.1 mL of the BSTFA reagent (1% TMCS, v/v) was added into samples and they were oscillated at 70 °C for 1 h. After the simples temperature fell to room temperature, the GC–MS analysis was performed using an Agilent 7890 gas chromatograph system coupled to a Pegasus HT time-of-flight mass spectrometer (NYSE: A, Beijing City, China). A 1 μL of aliquot of the analyte was injected in splitless mode. Helium was used as the carrier gas with a flow rate of 20 mL min− 1 and the front inlet purge flow was 3 mL min− 1. The column temperature was maintained at 50 °C for the first 1 min and then was increased at a rate of 10 °C min− 1 until it reached 330 °C. The temperature was kept at 330 °C for 5 min. Ionization in the injection, transfer line, and ion source at 280, 280, and 220 °C, respectively, was coupled with electron energy of − 70 eV. Mass spectra data were recorded in the 85–650 m z− 1 range at a rate of 20 spectra [61, 62].

Data processing and multivariate data analysis

The data were pre-processed by the manufacturer’s ChromaTOF software (versions 2.12, 2.22, 3.34; LECO, St. Joseph, MI, USA) [62]. The metabolites were identified by searching the commercial EI-MS and the FiehnLib libraries [63]. At least 80% of missing values were removed. These missing values were replaced with a small value, which was half of the minimum positive value in the original data. Then, the data were filtered using the IQR. In addition, the total mass of the signal integration area was normalized for each sample. Then the major metabolites were analyzed using Student’s T test (p < 0.05) and their similarity values if they were more than 500. Next, the normalized data were fed into the SIMCA-P 13.0 software package (Umetrics, Umea, Sweden) for PCA, PLS-DA, OPLS-DA. Subsequently, the metabolic pathway was constructed according to KEGG (http-://www.genome.jp/kegg/) and the pathway was analyzed using the MetaboAnalyst website (http://http://www.metaboanalyst.ca/), which was based on the change in metabolite concentration compared to the corresponding controls [64, 65].

Availability of data and materials

The datasets generated and analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- 3-PGA:

-

3-phosphoglycerate phosphatase

- AS:

-

Asparagine synthetase

- F-6-P:

-

Fructose-6-phosphate

- Fd-GOGAT:

-

Ferredoxin-dependent glutamate synthase

- G-6-P:

-

Glucose-6-phosphate

- GABA:

-

γ-aminobutyric acid

- GS:

-

Glutamine synthetase

- PEP:

-

Phosphoenolpyruvate

References

Arun M, Radhakrishnan R, Ai TN, Naing AH, Lee IJ, Kim CK. Nitrogenous compounds enhance the growth of petunia and reprogram biochemical changes against the adverse effect of salinity. J Hortic Sci Biotechnol. 2016;91:562–72.

Xu G, Fan X, Miller AJ. Plant nitrogen assimilation and use efficiency. Annu Rev Plant Biol. 2012;63:153–82.

Xie M, Chung CY-L, Li M-W, Wong F-L, Wang X, Liu A, et al. A reference-grade wild soybean genome. Nat Commun. 2019;10:1216. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-019-09142-9.

Nawaz MA, Yang SH, Chung G. Wild soybeans: an opportunistic resource for soybean improvement. Rediscovery of Landraces as a Resource for the Future (September). 2018.

Li W, Zhang H, Li X, Zhang F, Liu C, Du Y, et al. Intergrative metabolomic and transcriptomic analyses unveil nutrient remobilization events in leaf senescence of tobacco. Sci Rep. 2017;7:1–17.

Beatty P, Klein M, Fischer J, Lewis I, Muench D, Good A. Understanding plant nitrogen metabolism through metabolomics and computational approaches. Plants. 2016;5:39. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants5040039.

Gaju O, Allard V, Martre P, Le Gouis J, Moreau D, Bogard M, et al. Nitrogen partitioning and remobilization in relation to leaf senescence, grain yield and grain nitrogen concentration in wheat cultivars. F Crop Res. 2014;155:213–23.

Shao S, Li MX, Yang DS, Zhang J, Shi LX. The physiological variations of apaptation mechaniam in Glycine soja seedings under saline and alkaline stresses. Pak J Bot. 2016;48:2183–93.

Li MX, Xu JS, Guo R, Liu Y, Wang SY, Wang H, et al. Identifying the metabolomics and physiological differences among Soja in the early flowering stage. Plant Physiol Biochem. 2019;139:82–91.

Rui Guo, Lianxuan Shi, Yang Jiao, Mingxia Li, Xiuli Zhong, Fengxue Gu, et al. Metabolic responses to drought stress in the tissues of drought-tolerant and drought-sensitive wheat genotype seedlings. AoB PLANTS. 2018;10(2). ply016.

Li MX, Guo R, Jiao Y, Jin XF, Zhang HY, Shi LX. Comparison of salt tolerance in Soja based on metabolomics of seedling roots. Front Plant Sci. 2017;8:1101. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpls.2017.01101.

Arbona V, Manzi M, de Ollas C, Gómez-Cadenas A. Metabolomics as a tool to investigate abiotic stress tolerance in plants. Int J Mol Sci. 2013;14:4885–911.

Zhang J, Yang DS, Li MX, Shi LX. Metabolic profiles reveal changes in wild and cultivated soybean seedling leaves under salt Stress. PLoS ONE 11(7): e0159622.

Hörtensteiner S, Feller U. Nitrogen metabolism and remobilization during senescence. J Exp Bot. 2002;53:927–37.

Feller U, Fischer A. Nitrogen metabolism in senescing leaves. Crit Rev Plant Sci. 1994;13(3):241–73.

Hill J. The remobilization of nutrients from leaves. J Plant Nutr. 1980;2:407–44.

Fan S-C, Lin C-S, Hsu P-K, Lin S-H, Tsay Y-F. The Arabidopsis nitrate transporter NRT1.7, expressed in phloem, is responsible for source-to-sink remobilization of nitrate. Plant Cell Online. 2009;21:2750–61. https://doi.org/10.1105/tpc.109.067603.

Wang Y, Tsuda K, Ziegler J, Garrido-Oter R, Mine A, Schulze-Lefert P, et al. Balancing trade-offs between biotic and abiotic stress responses through leaf age-dependent variation in stress hormone cross-talk. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2019;116:2364–73.

Kusuda H, Koga W, Kusano M, Oikawa A, Saito K, Hirai MY, et al. Ectopic expression of myo-inositol 3-phosphate synthase induces a wide range of metabolic changes and confers salt tolerance in rice. Plant Sci. 2015;232:49–56. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.plantsci.2014.12.009.

Allwood JW, Chandra S, Xu Y, Dunn WB, Correa E, Hopkins L, et al. Profiling of spatial metabolite distributions in wheat leaves under normal and nitrate limiting conditions. Phytochemistry. 2015;115:99–111.

Guo R, Shi L, Yang C, Yan C, Zhong X, Liu Q. Comparison of Ionomic and Metabolites Response under Alkali Stress in Old and Young Leaves of Cotton ( Gossypium hirsutum L .) Seedlings. Front. Plant Sci. 7:1785. doi: https://doi.org/10.3389/fpls.2016.01785

Guiboileau A, Avila-Ospina L, Yoshimoto K, Soulay F, Azzopardi M, Marmagne A, et al. Physiological and metabolic consequences of autophagy deficiency for the management of nitrogen and protein resources in Arabidopsis leaves depending on nitrate availability. New Phytol. 2013;199:683–94.

Schmelz EA, Alborn HT, Engelberth J, Tumlinson JH. Nitrogen Deficiency Increases Volicitin-Induced Volatile Emission , Jasmonic Acid Accumulation , and Ethylene Sensitivity in Maize. Plant Physiol, September 2003; 133: 295–306.

Li MX, Xu JS, Wang XX, Fu H, Zhao ML, Wang H, et al. Photosynthetic characteristics and metabolic analyses of two soybean genotypes revealed adaptive strategies to low-nitrogen stress. J Plant Physiol. 2018;229:132–41.

Alves AA, Guimarães LM da S, Chaves AR de M, DaMatta FM, Alfenas AC. Leaf gas exchange and chlorophyll a fluorescence of Eucalyptus urophylla in response to Puccinia psidii infection. Acta Physiol Plant 2011;33:1831–1839.

Long SP, Bernacchi CJ. Gas exchange measurements, what can they tell us about the underlying limitations to photosynthesis? Procedures and sources of error. J Exp Bot. 2003;54:2393–401.

Schachtman DP, Shin R. Nutrient sensing and signaling: NPKS. Annu Rev Plant Biol. 2007;58:47–69.

Lecourt J, Lauvergeat V, Ollat N, Vivin P, Cookson SJ. Shoot and root ionome responses to nitrate supply in grafted grapevines are rootstock genotype dependent. Aust J Grape Wine Res. 2015;21:311–8.

Wu D, Shen Q, Cai S, Chen ZH, Dai F, Zhang G. Ionomic responses and correlations between elements and metabolites under salt stress in wild and cultivated barley. Plant Cell Physiol. 2013;54:1976–88.

Borlotti A, Vigani G, Zocchi G. Iron deficiency affects nitrogen metabolism in cucumber (Cucumis sativus L.) plants. BMC Plant Biol. 2012;12:1–15.

Koshiba T etal. Boron deficiency. Plant Signal Behav. 2009;4:557–558.

Zhang C, Zhou C, Burnap RL, Peng L. Carbon / Nitrogen Metabolic Balance : Lessons from Cyanobacteria. Trends Plant Sci. 2018;xx:1–15. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tplants.2018.09.008.

Santos-Filho PR, Saviani EE, Salgado I, Oliveira HC. The effect of nitrate assimilation deficiency on the carbon and nitrogen status of Arabidopsis thaliana plants. Amino Acids. 2014;46:1121–9.

Streeter JG, Lohnes DG, Fioritto RJ. Patterns of pinitol accumulation in soybean plants and relationships to drought tolerance. Plant Cell Environ. 2001;24:429–38.

Dumschott K, Richter A, Loescher W, Merchant A. Post photosynthetic carbon partitioning to sugar alcohols and consequences for plant growth. Phytochemistry. 2017;144:243–52.

Noiraud N, Maurousset L, Lemoine R. Transport of polyols in higher plants. Plant Physiol Biochem. 2001;39:717–28.

Merchant A, Richter AA. Polyols as biomarkers and bioindicators for 21st century plant breeding. Funct Plant Biol. 2011;38:934–40.

López-Bucio J, Nieto-Jacobo MF, Ramírez-Rodríguez V, Herrera-Estrella L. Organic acid metabolism in plants: from adaptive physiology to transgenic varieties for cultivation in extreme soils. Plant Sci. 2000;160:1–13.

Scheible WR. Nitrate acts as a signal to induce organic acid metabolism and repress starch metabolism in tobacco. Plant Cell Online. 1997;9:783–98. https://doi.org/10.1105/tpc.9.5.783.

Touraine B, Muller B, Grignon C. Effect of Phloem-Translocated Malate on N03- Uptake by Roots of Intact Soybean Plants . 1992;:1118–1123.

Dixon RA, Achnine L, Kota P, Liu CJ, Reddy MSS, Wang L. The phenylpropanoid pathway and plant defence - a genomics perspective. Mol Plant Pathol. 2002;3(5):371–90.

Zhang X, Liu CJ. Multifaceted regulations of gateway enzyme phenylalanine ammonia-lyase in the biosynthesis of phenylpropanoids. Mol Plant. 2015;8:17–27.

Narasimhan K, Basheer C, Bajic VB, Swarup S. Enhancement of plant-microbe interactions using a rhizosphere metabolomics-driven polychlorinated biphenyls. Society. 2003;132(5):146–53.

Clúa J, Roda C, Zanetti ME, Blanco FA. Compatibility between legumes and rhizobia for the establishment of a successful nitrogen-fixing symbiosis. Genes (Basel). 2018;9:125.

Dixon RA, Paiva NL. Stress-induced Phenylpropanoid metabolism. Plant Cell. 1995;7:1085–97.

Plaxton WC. The organization and regulation of plant glycolysis. Annu Rev Plant Physiol Plant Mol Biol. 1996;47:185–214.

Wiskich J.T., Dry I.B. The Tricarboxylic Acid Cycle in Plant Mitochondria: Its Operation and Regulation. In: Douce R., Day D.A. (eds) Higher Plant Cell Respiration. Encyclopedia of Plant Physiology (New Series). 1985; 18.

Braun H, Hildebrandt TM, Nesi AN, Arau WL. Amino Acid Catabolism in Plants. 2015; November:1563–1579.

Pratelli R, Pilot G. Regulation of amino acid metabolic enzymes and transporters in plants. J Exp Bot. 2014;65:5535–56.

Filippou P, Antoniou C, Fotopoulos V. The nitric oxide donor sodium nitroprusside regulates polyamine and proline metabolism in leaves of Medicago truncatula plants. Free Radic Biol Med. 2013;56:172–83.

Lam H-M, Coschigano KT, Oliveira IC, Melo-Oliveira R, Coruzzi GM. The molecular-genetics of nitrogen assimilation into amino acids in higeher plant. Annu Rev Plant Physiol Plant Mol Biol. 1996;47:569–93.

Duff SMG, Qi Q, Reich T, Wu X, Brown T, Crowley JH, et al. Plant physiology and biochemistry a kinetic comparison of asparagine synthetase isozymes from higher plants. Plant Physiol Biochem. 2011;49:251–6. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.plaphy.2010.12.006.

Lea PJ, Sodek L. Parry MAJ. Halford NG. Asparagine in plants. Annals of Applied Biology: Shewry PR; 2007.

Lea PJ, Sodek L, Parry MAJ, et al. Asparagine in plants. Ann Appl Biol. 2010;150(1):1–26.

Sieciechowicz KA, Joy KW, Ireland RJ. The metabolism of asparagine in plants. Phytochemistry. 1988;27(3):663–71.

Kinnersley AM, Turano FJ. Gamma aminobutyric acid ( GABA ) and plant responses to stress. Crit Rev Plant Sci. 2016;19(6):479–509.

Ma Y, Wang P, Chen Z, Gu Z, Yang R. GABA enhances physio-biochemical metabolism and antioxidant capacity of germinated hulless barley under NaCl stress. J Plant Physiol. 2018;231 April:192–201.

Kinnersley AM, Turano FJ. Gamma aminobutyric acid (GABA) and plant responses to stress. CRC Crit Rev Plant Sci. 2000;19:479–509.

Kim J, Woo HRR, Nam HGG. Toward systems understanding of leaf senescence: an integrated multi-omics perspective on leaf senescence research. Mol Plant. 2016;9:813–25.

Jiao Y, Bai ZZ, Xu JS, Zhao ML, Khan Y, Hu Y, et al. Metabolomics and its physiological regulation process reveal the salt-tolerant mechanism in Glycine soja seedling roots. Plant Physiol Biochem. 2018.

Bocian A, Zwierzykowski Z, Rapacz M, Koczyk G, Ciesiołka D, Kosmala A. Metabolite profiling during cold acclimation of Lolium perenne genotypes distinct in the level of frost tolerance. J Appl Genet. 2015;56:439–49.

Kind T, Wohlgemuth G, Lee DY, Lu Y, Palazoglu M, Shahbaz S, et al. FiehnLib: mass spectral and retention index libraries for metabolomics based on quadrupole and time-of-flight gas chromatography/mass spectrometry. Anal Chem. 2009;81:10038–48.

Luedemann A, de Koning S, Lommen A, Goodacre R, Kay L, Erban A, et al. Inter-laboratory reproducibility of fast gas chromatography–electron impact–time of flight mass spectrometry (GC–EI–TOF/MS) based plant metabolomics. Metabolomics. 2009;5:479–96.

Xia J, Mandal R, Sinelnikov IV, Broadhurst D, Wishart DS. MetaboAnalyst 2.0-a comprehensive server for metabolomic data analysis. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012;40:127–33.

Yang DS, Zhang J, Li MX, Shi LX. Metabolomics analysis reveals the salt-tolerant mechanism in Glycine soja. J Plant Growth Regul. 2017;36:460–71.

Acknowledgements

We thank Jilin Academy of Agriculture Science for kindly helping to provide soybean seeds.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 31870278).

We deeply thank National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 31870278) for their financial supports to this research, including experimental implementation, sampling and data analysis.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

YL and SX designed the research; YL, ML, JX, XL and SW performed the research; YL and ML analyzed the data; YL and SX wrote the article. All authors have read, edited and approved the current version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Additional files

Additional files 1:

The growth performances in young and old leaves of two soybean varieties under LN stress. C, cultivated soybean; W, wild soybean; CK, control treatment; LN, low nitrogen stress; Up FW, aboveground fresh weight; Up DW, aboveground dry weight; Under FW, underground fresh weight; Under DW, underground dry weight. * and ** indicate significant (P < 0.05) and highly significant (P < 0.01) differences, respectively. (DOCX 13 kb)

Additional file 2:

The contributions of ions among young and old leaves of W and C seedlings to the first principal component (PC1) and the second principal component (PC2). C, cultivar soybean; W, wild soybean; CK, control treatment; LN, low-nitrogen stress (XLSX 12 kb)

Additional file 3:

Total ion current chromatograms of two genotypes soybean seedling leaves extracts obtained from GC-MS. A: W-YL-CK; B: W-YL-LN; C: W-OL-CK; D: W-OL-LN; E: C-YL-CK; F: C-YL-LN; G: C-OL-CK; H: W-OL-LN. (DOCX 1139 kb)

Additional file 4:

The contributions of metabolites among young leaves of W and C seedlings to the first principal component (PC1) and the second principal component (PC2). C, cultivar soybean; W, wild soybean; CK, control treatment; LN, low-nitrogen stress (XLSX 14 kb)

Additional file 5:

The contributions of metabolites among old leaves of W and C seedlings to the first principal component (PC1) and the second principal component (PC2). C, cultivar soybean; W, wild soybean; CK, control treatment; LN, low-nitrogen stress (XLSX 15 kb)

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Liu, Y., Li, M., Xu, J. et al. Physiological and metabolomics analyses of young and old leaves from wild and cultivated soybean seedlings under low-nitrogen conditions. BMC Plant Biol 19, 389 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12870-019-2005-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12870-019-2005-6