Abstract

Background

The natural course of sexually transmitted infections caused by Chlamydia trachomatis varies between individuals. In addition to parasite and host effects, the vaginal microbiota might play a key role in the outcome of C. trachomatis infections. Interferon-gamma (IFN-γ), known for its anti-chlamydial properties, activates the expression of indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase (IDO1) in epithelial cells, an enzyme that catabolizes the amino acid L- tryptophan into N-formylkynurenine, depleting the host cell’s pool of tryptophan. Although C. trachomatis is a tryptophan auxotroph, urogenital strains (but not ocular strains) have been shown in vitro to have the ability to produce tryptophan from indole using the tryptophan synthase (trpBA) gene. It has been suggested that indole producing bacteria from the vaginal microbiota could influence the outcome of Chlamydia infection.

Results

We used two in vitro models (treatment with IFN-γ or direct limitation of tryptophan), to study the effects of direct rescue by the addition of exogenous indole, or by the addition of culture supernatant from indole-positive versus indole-negative Prevotella strains, on the growth and infectivity of C. trachomatis. We found that only supernatants from the indole-positive strains, P. intermedia and P. nigrescens, were able to rescue tryptophan-starved C. trachomatis. In addition, we analyzed vaginal secretion samples to determine physiological indole concentrations. In spite of the complexity of vaginal secretions, we demonstrated that for some vaginal specimens with higher indole levels, there was a link to higher recovery of the Chlamydia under tryptophan-starved conditions, lending preliminary support to the critical role of the IFN-γ-tryptophan-indole axis in vivo.

Conclusions

Our data provide evidence for the ability of both exogenous indole as well as supernatant from indole producing bacteria such as Prevotella, to rescue genital C. trachomatis from tryptophan starvation. This adds weight to the hypothesis that the vaginal microbiota (particularly from women with lower levels of lactobacilli and higher levels of indole producing anaerobes) may be intrinsically linked to the outcome of chlamydial infections in some women.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Chlamydia trachomatis is an obligate intracellular bacterium with a unique biphasic developmental cycle. The cycle begins with the uptake of the infectious elementary body form (EB) by the host cell. The EB remains in a membrane-bound vacuole termed an inclusion, where it differentiates into the non-infectious, reticulate body form (RB). The RBs undergo cell division. After 8–12 rounds of multiplication, and inclusion growth, RBs asynchronously convert back to the EB form [1, 2]. At 30–68 h post infection (PI), depending on the infecting strain, the EBs are released from the host cell [3]. However, under stressful growth conditions such as nutrient starvation, exposure to antibiotics or immune factors such as interferon-gamma (IFN-γ) [4–6], the chlamydial cycle is disturbed and the RBs convert to enlarged, non-infectious, aberrant bodies (ABs) [1, 3, 7, 8]. Once the stress factor is removed, the Chlamydia revert to the active developmental cycle [3, 8, 9].

Genital C. trachomatis infections remain a major health problem. Worldwide, an estimated 131 million sexually transmitted C. trachomatis infections occur each year [10]. In women, the severity of the infection as well as the probability to progress to complications varies among individuals. Complications such as pelvic inflammatory disease (PID) and infertility are common following C. trachomatis infection [11–13] and may be associated with the participant’s inability to fully clear their infection, or a history of repeat infections [13–16]. The proinflammatory cytokine interferon-γ (IFN-γ) is known for its central role in inflammation and autoimmunity [17]. This cytokine is upregulated upon infection [18, 19] and has inhibitory effects on C. trachomatis [19, 20]. IFN-γ has many effects but for Chlamydia most significant appears to be the induction of expression of the enzyme indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase (IDO), in epithelial cells, that catalyses the degradation of the essential amino acid, L-tryptophan into N-formylkynurenine [21]. Depletion of the host cell tryptophan pools causes the Chlamydia, a tryptophan auxotroph, to enter its persistent form [22], evident in vitro by enlarged, aberrant bodies (ABs) (or die at severe depletion) [5, 23]. When the tryptophan is restored, in vitro evidence shows that the Chlamydia returns back to its infectious state [24, 25]. While different chlamydial strains have a range of sensitivity levels to IFN-γ treatment in vitro [9, 26], high concentrations are lethal. C. trachomatis genital (D-L), but not ocular (A-C) strains, have a functional tryptophan synthase gene (trpBA) [25–28], which enables them to synthesise tryptophan from indole. Addition of exogenous indole to the cell culture, can rescue the genital C. trachomatis strains from IFN-γ exposure, enabling them to subsequently produce infectious progeny [27, 29, 30].

In addition to the host immune response [16], C. trachomatis infection risk is increased during episodes of bacterial vaginosis (BV), which is characterized by reduced levels of lactobacilli and a higher proportion of anaerobic bacteria in the vaginal tract [31–34]. One hypothesis described by Morrison et al. [35], suggested that indole producing bacteria in the vaginal flora might contribute to the survival of the Chlamydia by providing a source of indole at the infection site [24, 27, 35–37]. In this study, we directly investigated the effect of indole producing bacteria, such as Prevotella, on C. trachomatis recovery after tryptophan starvation. Our results show that supernatant from indole producing Prevotella intermedia and Prevotella nigrescens, but not indole negative Prevotella bivia, can rescue C. trachomatis after tryptophan starvation in vitro. In addition, vaginal secretions from five women had different effects on the recovery of the Chlamydia after tryptophan starvation.

Methods

C. trachomatis in vitro culture conditions

The C. trachomatis isolates used in this study included: C. trachomatis serotype D (ATCC VR-885), C. trachomatis serotype C (ATCC VR-1477). Isolates were routinely cultured in HEp-2 cell line (ATCC CCL-23) with DMEM (Gibco, Australia) containing 5% heat inactivated fetal calf serum (FCS) (Life Technologies, Australia), 120 μg/ml streptomycin (Sigma-Aldrich, Australia), 50 μg/ml Gentamycin (Gibco, Australia), 37 °C, 5% CO2. All experiments were conducted in 48-well plates at a multiplicity of infection (MOI) of 0.5. For the IFN-γ-induced tryptophan starvations experiments; 25,000 cells/well were seeded 48 h before infection, in the presence of different concentrations of human IFN-γ (Peprotech, Australia). IFN-γ treatment was replenished every 24 h until the rescue time point. For the tryptophan-depleted media experiments (Jomar Life Research, Australia), 50,000 cells/well were seeded 24 h before infection. At the time of infection, the HEp-2 monolayer was at around 90% confluence. Fresh media and appropriate treatments were supplied to the culture every 24 h and the infectious yields were measured at 36/60/72 h PI (depends on the specific experiment- see figures legend). Infected cells and culture supernatants were then sonicated and used to infect a new HEp-2 cell monolayer in three replicates, for enumeration of recoverable inclusion forming units (IFUs). After staining with anti-HtrA and goat anti rabbit IgG (H + L) Alexa Flour 488 (Invitrogen, Australia), wells were visualized for inclusion presence using fluorescence microscopy (Nikon Eclipse TiS Fluorescent Microscope) [38, 39]. The IFU/ml were determined for each condition by measuring the number of inclusions in multiple wells, taking into account the dilution and volume from the original culture. The limit of detection of the assay is 102 IFU/ml. Rescue experiments using an IFN-γ-induced tryptophan starvation model were conducted following three washes with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS). Rescue experiments using tryptophan-depleted media were conducted with the addition of tryptophan, indole, bacterial isolates supernatant or cervical secretions, in the presence of cycloheximide, at 36 h PI and were incubated for further 36 h. Control cultures with normal tryptophan supply, as well as tryptophan-depleted conditions without rescue, were included in all experiments. In all ‘No rescue’ treatments, cultures were harvested to check chlamydial recovery at 36 h PI. Morphological observation of the chlamydial inclusions in tryptophan-depleted media was made in several of the treatments using Chlamydia LPS stain (Cellabs, Australia) and visualised using confocal microscopy (Nikon Eclipse Ti) (Additional file 1: Figure S1). For the morphological observations, cultures were fixed with methanol at 36 h PI (Additional file 1: Figure S1A), and at 72 h PI (Additional file 1: Figure S1B, C).

In vitro rescue of C. trachomatis with supernatant from indole positive/negative bacteria

Indole producing bacteria, P. intermedia (ATCC 25611) and P. nigrescens (ATCC 33563), and a non-indole producing bacterium P. bivia (vaginal isolate), were cultured in BHI broth 37 °C/36 h in anaerobic conditions. OD600 was measured and corrected for all strains to OD = 1. Indole production was confirmed using Kovac’s reagent (Sigma-Aldrich, Australia). Bacterial broth was centrifuged 3000 × g/10 min/RT and supernatant was collected and filter sterilised with 0.22 μM filter. Supernatant was added to the tryptophan-deprived C. trachomatis infected cell culture at 36 h PI. Infected cells and culture supernatants were sonicated at 72 h PI and were used to infect a new HEp-2 cell monolayer for enumeration of recoverable IFUs.

RNA extraction and reverse transcription

C. trachomatis infected cell culture samples were stored in RNAlater. Total RNA was extracted from the cells using RNeasy mini kit (Qiagen, Australia), according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The RNA concentration and purity was determined using Nano-drop Spectrophotometer. 0.2 μg of total RNA was reverse transcribed using QuantiTect Reverse transcription kit (Qiagen, Australia), in accordance with the manufacturer’s instructions.

C. trachomatis trpBA transcript expression

The primers sequences were taken from Carlson et al., paper [30], with minor changes to complement C. trachomatis serotype D. Forward primer for trpBA amplification: 5′-GCATTGGAGTCTTCACATGC-3′, and reverse primer: ′3-ACACCTCCTTGAATCAGAGC-5′. Amplification was carried out according to the manufacturer’s instructions using QuntiNova SYBR Green PCR kit (Qiagen, Australia). The cycling program was 95 °C for 2 min followed by 40 cycles of 5 s at 95 °C and 10 s at 60 °C. Transcript levels were quantified using Rotor-GeneQ (Qiagen, Australia). Results were normalized against the mRNA of C. trachomatis-specific ompA gene transcripts (using previously described primers [40]) in each cDNA preparation. Results are presented as normalised values of 2-ΔΔCT.

Elution of vaginal secretions and Indole concentration measurement

LASIK PVA eye sponges (Visitec) were placed in the posterior fornix of the vagina for two min to absorb secretions [41]. Sponges were immediately placed in −20 °C until vaginal fluid was extracted the same day. Vaginal fluid was eluted from sponges using 300 μl of PBS. Total indoles were quantified using Salkowski’s test [42], modified as described by Szkop et al. [43]. Briefly, serial dilutions of indole (Sigma-Aldrich, Australia) were used in order to generate a standard curve by measuring absorbance at 530 nm, following incubation with Salkowski’s reagent. Indole concentrations were corrected for the dilution factor of the samples.

Participant details and sample collection procedures

Samples were collected from a small study in reproductive-age women who were either, negative for, or infected with C. trachomatis, attending the sexual health clinic in Nambour, Australia. All participants provided informed written consent to participate in the study. Two Chlamydia negative and three Chlamydia positive women were recruited to the study. Chlamydia testing (positive/negative) was performed by the Nambour STI Clinic. High vaginal swab sample and cervical secretion sample were collected from each participant to enumerate chlamydial infection load and indole concentration. Participants’ secretion samples were evaluated for their indole content as described above. Secretions were added to the tryptophan-starved culture at 36 h PI to evaluate the Chlamydia recovery effect. The secretions were added in different dilutions; 1:100, 1:1000, 1:10,000, as well as secretions at 1:10,000 dilution with the addition of 0.5 μM indole (Additional file 2: Figure S2).

Statistical analyses

All cell culture experiments (Figs. 1, 2, 3, 4, 5 and 6) were conducted in triplicate. The IFU/ml was determined for each condition by measuring the number of inclusions in multiple wells, and accounting for the dilution and volume from the original culture. Data were analysed using Prism GraphPad V.6 and presented as the mean ± SD IFUs (n = 9) determinations. Statistical significance in Fig. 6 was determined using two-way ANOVA and p- values were calculated using Tukey’s multiple comparison test. For Fig. 4 statistical significance was determined via multiple t testing using the Holm-Sidak method, with alpha = 0.05, while each row was analyzed individually, without assuming a consistent SD.

Recovery of IFN-γ treated C. trachomatis (ocular; C and genital; D strains), with tryptophan (DMEM) and indole (10 μM). Monolayers of HEp-2 cells were seeded 48 h before infection in the presence of different IFN-γ concentrations (0, 150, 500 U/ml). IFN-γ treatment was replenished every 24 h throughout the whole experiment. Cells were infected with C. trachomatis D, at an MOI of 0.5, and were incubated for 36 h. The Chlamydia infected cultures were allowed to recover for 24 h in the presence of tryptophan (DMEM) or indole (10 μM). Infected cells and culture supernatants were sonicated and used to infect a new HEp-2 cell monolayer for enumeration of recoverable IFUs. Data are presented as the mean ± SD IFU/ml (n = 9) determinations

Effect of different indole concentrations on the recovery of C. trachomatis D following IFN-γ treatment. Monolayers of HEp-2 cells were seeded 48 h before infection in the presence of different IFN-γ concentrations (0, 150, 500 U/ml). IFN-γ treatment was replenished every 24 h throughout the whole experiment. Cells were infected with C. trachomatis D, at an MOI of 0.5, and were incubated for 36 h. The Chlamydia infected cultures were allowed to recover for 24 h with different indole concentrations (0.1, 0.25, 0.5, 1 μM). Infected cells and culture supernatants were sonicated and used to infect a new HEp-2 cell monolayer for enumeration of recoverable IFUs. Data are presented as the mean ± SD IFU/ml (n = 9) determinations

Recovery of tryptophan-starved C. trachomatis strain D after rescue with exogenous tryptophan (122–980 μM) or indole (0.1–10 μM). Monolayers of HEp-2 cells were seeded in the presence of tryptophan-depleted media 24 h before infection. Cells were infected with C. trachomatis D, at an MOI of 0.5, and were incubated for 36 h. The Chlamydia infected cultures were allowed to recover for 36 h with increasing concentrations of tryptophan (a) or indole (b). Infected cells and culture supernatants were sonicated and used to infect a new HEp-2 cell monolayer for enumeration of recoverable IFUs. Data are presented as the mean ± SD IFU/ml (n = 9) determinations

Recovery of tryptophan-starved C. trachomatis strain D after rescue with supernatant from indole positive/indole negative bacteria. Monolayers of HEp-2 cells were seeded in the presence of tryptophan-depleted media 24 h before infection. Cells were infected with C. trachomatis D, at an MOI of 0.5, and were incubated for 36 h. The Chlamydia infected cultures were allowed to recover for 36 h in the presence of (a) supernatant from indole producing P. intermedia and P. nigrescens, and a non-indole producer P. bivia. Data are presented in dilution of 1:10,000. P. bivia is significantly different (p < 0.0001). Indole concentrations measured from the growth medium of P. intermedia and P. nigrescens were 300 μM and 250 μM respectively. b A control of the bacterial growth broth (BHI) was added as well. All treatments were added in different dilutions of 1:1000, 1:5000 and 1:10,000 (Additional file 3: Figure S3). Infected cells and culture supernatants were sonicated and used to infect a new HEp-2 cell monolayer for enumeration of recoverable IFUs. Data are presented as the mean ± SD IFU/ml (n = 9) determinations. Statistical significance determined via multiple t testing using the Holm-Sidak method, with alpha = 0.05. Each row was analyzed individually, without assuming a consistent SD

Recovery of tryptophan-starved C. trachomatis strain D after rescue with secretions from five (Chlamydia positive/negative) participants that have different concentrations of indole in their vaginal secretions. Monolayers of HEp-2 cells were seeded in the presence of tryptophan-depleted media 24 h before infection. Cells were infected with C. trachomatis D, at an MOI of 0.5, and were incubated for 36 h. The Chlamydia infected cultures were allowed to recover for 36 h in the presence of secretions from two C. trachomatis negative participants (111 and 112) and three C. trachomatis positive participants (213, 211 and 306). Chlamydia test (CT+/CT-), pH and BV conditions are indicated in boxes above each participant. Secretions were added to the cultures at dilution of 1:100. Axis X represent the indole concentrations measured from the participants’ secretions, axis Y represent the recovery effect of the Chlamydia in IFU/ml. Infected cells and culture supernatants were sonicated and used to infect a new HEp-2 cell monolayer for enumeration of recoverable IFUs. Data are presented as the mean ± SD IFU/ml (n = 9) determinations

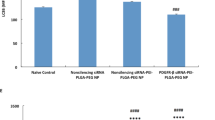

RT-qPCR quantitation of trpBA gene mRNA, isolated from HEp-2 cells, infected with C. trachomatis strain D during tryptophan starvation conditions and rescue. C. trachomatis infected cultures and conditions were as described in the legend of Figs. 4 and 5. a Total RNA was isolated from infected cultures grown in tryptophan-depleted media at 72 h PI (‘No rescue’), and after indole rescue in different concentrations (0.5, 5 μM), as well as complete DMEM conditions harvested at 36 and 72 h PI (‘DMEM’). No rescue treatment is significantly different p < 0.0001. b trpBA transcript levels were measured from rescue treatments of infected cultures using indole positive bacterial supernatant (P. intermedia, P. nigrescens) and indole negative (P. bivia), applied in dilution of 1:10,000. P. bivia is significantly different p < 0.005

Results

IFN-γ- induced tryptophan starvation and rescue

We first established an in vitro assay using IFN-γ treated HEp-2 cells, infected with either C. trachomatis genital (serovar D) or ocular (serovar C) strains, and demonstrated different abilities of these strains to recover following the addition of tryptophan (fresh ‘DMEM’) or indole (10 μM) (Fig. 1), after IFN-γ treatment. HEp-2 cells were infected with C. trachomatis and incubated in the presence of different IFN-γ concentrations (0, 150, 500 U/ml) for 36 h. At the time of recovery; 36 h PI, without rescue (‘No rescue’ treatment), no inclusions were detected. Consistent with the literature, our data showed that both strains were able to recover from IFN-γ treatment (36 h) when the IFN-γ was removed and replaced with fresh DMEM containing 78.3 μM (16 mg/L) L-tryptophan (as per the manufacturer’s description). For C. trachomatis D, treatment with 500 units of IFN-γ resulted in no remaining infectious organisms but when fresh DMEM was added, 4.9 × 103 IFUs/ml were recovered. The ocular strain, C, showed 1.2 × 102 IFU/ml recovery under similar conditions. When exogenous indole (rather than DMEM containing exogenous tryptophan) was used for the recovery step, the genital strain D showed a very high (2.1 × 105) recovery of IFUs/ml, as there was no competition from the host cell for indole, whereas the ocular strain C did not show any additional recovery (compared to DMEM alone). Next, we investigated a range of exogenous indole concentrations on recovery and found that levels of 0.25 μM and higher resulted in high levels of recovery, even when the cultures were originally treated with 1000 units/ml of IFN-γ (Fig. 2).

C. trachomatis D recovery using tryptophan or indole in a tryptophan-depleted media model

The model of C. trachomatis inhibition using IFN-γ, cultured with DMEM, is problematic, as the media contains large amounts of tryptophan. Therefore, we used a model using tryptophan-depleted media, and added increasing concentrations of tryptophan or indole at 36 h PI to rescue the C. trachomatis D from tryptophan starvation (Fig. 3a, b). Exogenous levels of tryptophan were able to effectively rescue the Chlamydia, with a maximum level of recovery of 2 × 104 IFU/ml, while there was no competition from the host cell over the tryptophan, as the cultures were treated with cycloheximide (Fig. 3a). Indole rescue on the other hand, showed a maximum recovery level of 7.6 × 104 IFU/ml with concentration dependent increase in the Chlamydia infectivity after tryptophan starvation (Fig. 3b). When no rescue treatment was used, there were no inclusions detected at 72 h PI (“No rescue”), as well as at the time of reactivation of the cultures; 36 h PI (data not shown).

C. trachomatis rescue using indole-producing bacterial supernatants

In order to investigate whether supernatant from indole producing bacteria could rescue Chlamydia, we chose two indole producing Prevotella spp. (P. intermedia and P. nigrescens) and one indole-negative strain, P. bivia. The bacteria were incubated in brain heart infusion (BHI) medium for 36 h. As the BHI growth medium contains tryptophan, we included the medium alone as a control and tested it at a range of dilutions (1:1000, 1:5000, and 1:10,000). Only supernatant from the indole-positive bacteria (P. intermedia and P. nigrescens) were able to rescue the Chlamydia at the critical dilution of 1:10,000 (Fig. 4) (p value < 0.0001 relative to BHI). By comparison, P. bivia, which is indole negative, was not able to rescue the Chlamydia at the same dilution (p value < 0.0001 relative to P. bivia). When no rescue treatment was used, there were no inclusions detectable, at 72 h PI, as well as at the time of reactivation of the cultures; 36 h PI (data not shown).

C. trachomatis rescue using vaginal secretions from Chlamydia positive and Chlamydia negative women

We utilised a combination of in vitro and ex vivo model to test the hypothesis that some of the vaginal indole-producing microbiota may counteract the immune system response mediated by IFN-γ, by providing a source of indole and allows the Chlamydia to survive under tryptophan-depleted conditions. Specifically, we tryptophan-starved the C. trachomatis D strain using tryptophan-depleted media. We then wanted to determine if vaginal secretions from different women was able to rescue the infectivity of Chlamydia to differing degrees, perhaps related to indole levels in these secretions. We therefore evaluated the Chlamydia recovery of infectivity compared with the participants’ chlamydial status (positive/negative) and the amount of indole in the vaginal secretions. The indole concentrations from the participants’ secretions (indicated in Fig. 5), ranged from 2.18 to 7.35 mM. Participant’s vaginal secretions were added to the C. trachomatis infected culture after tryptophan starvation for 36 h PI. We found higher recovery levels of the Chlamydia following rescue with secretions from participants 111 and 211 with relatively high indole concentrations (4.76 mM and 6.06 mM respectively) (Fig. 5). However, using secretions from participant 112 and 213 (who had relatively low indole concentrations in their secretions of 2.18 mM and 3.74 mM respectively), resulted in lower recovery of the C. trachomatis after tryptophan starvation in vitro (2 × 103 and 1.6 × 103 IFU/ml respectively). Across all five participants there was no linear correlation of indole and chlamydial recovery, however, four of the five participants were consistent with a trend of higher indole resulting in higher chlamydial infection. Spiking the participants’ secretions with 0.5 μM indole (at dilution of ‘1:10,000 + ’), eliminated some of the differences in the Chlamydia recovery that were found between the participants (at dilution of 1:100) (Additional file 3: Figure S3). No significant differences were observed between participant’s secretions treatments in dilutions 1:1000 and 1:10,000 (Additional file 3: Figure S3). When no rescue treatment was used, there were no inclusions detected, at 72 h PI, as well as at the time of reactivation of the cultures; 36 h PI (data not shown).

trpBA gene expression in tryptophan-starved C. trachomatis D following different rescue conditions

In an attempt to gain further support for the hypothesis, that the response of the tryptophan-starved C. trachomatis to the availability of tryptophan and indole (added as a rescue treatment 36 h PI) involves their tryptophan biosynthesis genes, we measured the mRNA expression levels of the trpBA gene in our indole-producing bacterial supernatant model (Fig. 6). Tryptophan starvation was shown to induce trpBA transcription levels in C. trachomatis culture (‘No rescue 72 h PI’. Fig. 6a). When exogenous tryptophan is provided via the DMEM medium, trpBA levels are switched off. (as expected), and hence any evidence of trpBA expression indicates a tryptophan starvation state of the Chlamydia. When exogenous indole was provided (at 0.5 and 5 μM), the trpBA gene expression levels were again increased to some extent, presumably to convert the indole to more tryptophan. (Fig. 6a). We then assessed the effect of adding bacterial supernatants (at various dilutions) to the chlamydial cultures and found that for P. bivia (indole negative) the chlamydial trpBA expression was high, confirming that they were tryptophan-starved (Fig. 6b). By comparison, the trpBA levels for the two indole positive bacteria (P. intermedia and P. nigrescens) were significantly lower (p value <0.05).

Discussion

In this study, we investigated the role of indole in the recovery of urogenital C. trachomatis infections following tryptophan starvation in vitro. The current hypothesis argues that the availability of indole in the lower genital tract site of women infected with C. trachomatis, can influence the level and outcome of the infection. Using both the established IFN-γ model as well as a tryptophan-depleted media model, we found that supernatants from the indole-positive bacteria, P. intermedia and P. nigrescens, but not indole-negative P. bivia, were able to recover C. trachomatis D infectivity when added to the cultures at dilution of 1:10,000. Although there is a range of bacterial products being produced by indole-positive bacteria cultured in broth medium, we assume that indole is a critical compound, which directly have a positive effect on C. trachomatis recovery after tryptophan starvation in vitro. Treatment with supernatant of indole-negative P. bivia and the control (BHI) were not sufficient to rescue the Chlamydia using the same dilution of 1:10,000. Because the amount of bacteria in a growth medium and the concentration of cytotoxic compounds are much higher than the levels found in vivo, we diluted the bacterial supernatants (1:1000, 1:5000 and 1:10,000). We also included a control of the bacterial growth broth (BHI). We have tested the BHI medium for tryptophan concentration, using commercial tryptophan ELISA kit (ImmuSmol, France), in order to validate our conclusion from this experiment. BHI medium contains 35 μg/ml (0.17 μM) tryptophan and therefore, it might have affected the recovery levels of the tryptophan-starved Chlamydia culture. However, when diluting the BHI medium to 1:10,000, the tryptophan in the medium itself was reduced to 3.5 ng/ml, which was previously shown to be insufficient for the recovery of Chlamydia after tryptophan starvation [22, 29]. Accordingly, BHI rescue treatment at a dilution of 1:1000 had significantly lower recovery compared to P. intermedia at the same dilution (p value <0.005, suggesting that indole in the P. intermedia supernatant had a beneficial effect, resulting in higher Chlamydia recovery in compare to the BHI control (Additional file 3: Figure S3).

Indole concentrations measured from the growth medium of P. intermedia and P. nigrescens were 300 μM and 250 μM respectively. When diluting the supernatant 1:1000, the indole concentration was decreased to 0.25–0.3 μM (Additional file 2: Figure S2). However, treatment with the indole-positive bacterial supernatant at this dilution, resulted in significantly higher recovery of the Chlamydia (P. intermedia: 6.8 × 104 IFU/ml, P. nigrescens: 3.1 × 104 IFU/ml) (p < 0.0001), in comparison to the control in which exogenous indole was directly added to a level of 0.5 μM (3.8 × 103 IFU/ml; Additional file 2: Figure S2). This suggests again that the recovery effect from the bacterial supernatant may be further increased as a result of the tryptophan content in the media, in addition to the indole produced by the indole-positive Prevotella.

Measurements of the chlamydial trpBA were conducted in order to confirm our recovery data during the different bacterial supernatant rescue treatments. Significantly higher expression levels in P. bivia supernatant rescue, suggested that there was no recovery of the tryptophan-starved Chlamydia via exogenous indole/tryptophan addition. This confirms our assumption that a non-indole producing bacterium such as P. bivia, is not able to rescue the Chlamydia after tryptophan starvation. trpBA measurements in indole positive bacterial supernatants (Fig. 6b) indicated lower expression levels in comparison to the tryptophan-starved Chlamydia (‘No rescue 72 h PI’; Fig. 6a), probably caused by the presence of indole in the media.

In order to investigate whether differences in the indole content in vaginal secretions of women who are negative for, or infected with C. trachomatis, have different effects on tryptophan-starved C. trachomatis recovery in vitro, we used the same tryptophan-depleted media model. We found that low indole content in secretions from participants 112 and 213 corresponded with lower Chlamydia recovery indicated by IFU/ml. Higher indole concentration in secretions from participants 111 and 211 corresponded with a higher Chlamydia recovery effect at a dilution of 1:100. This might suggest that high indole concentrations in the women’s secretions contribute to higher recovery of the tryptophan-starved C. trachomatis culture in vitro. C. trachomatis-positive participants 211 and 306 had considerably higher levels of indole in their secretions (7.35 mM and 6.6 mM respectively). This could indicate a link between Chlamydia infection status (positive/negative) and the indole concentrations measured from their genital secretions.

Individuals vary in their susceptibility to C. trachomatis infections, both new infections, as well as repeat infections [44–46]. While there are many factors that might contribute to this variation, such as individual sexual patterns [46], innate and adaptive immune response [47], the expression and release of the key cytokine IFN-γ [23], one additional factor that might influence this infection variation is the composition of the vaginal microbiome [33, 48, 49]. In most healthy women, lactobacilli are numerically dominant in the lower genital tract, providing protection against a range of pathogenic bacteria and resulting in a lower pH in this environment [50–53]. The replacement of lactobacilli by fastidious anaerobes, such as Prevotella spp., can result in higher pH, dysbiosis and bacterial vaginosis (BV) [48, 54]. It is well known that women with BV have a higher risk of acquiring sexually transmitted infections such C. trachomatis [33, 55, 56]. Some of these BV associated Prevotella are also indole positive, although this balance may well be quite different between different individuals. Indole production in the lower genital tract can also be associated with higher pH and lower numbers of lactobacilli. Our data clearly show that supernatant from indole positive but not indole negative Prevotella strains can rescue C. trachomatis from tryptophan starvation, in this in vitro model. It is possible that other indole-producing bacteria (e.g. Porphyromonas gingivalis, Propionibacterium acnes, Fusobacterium nucleatum, Escherichia coli or Enterococcus faecalis) which have been reported to colonize the genital tract in dysbiosis, could have a similar effect. If this hypothesis is confirmed, it opens up additional means of therapy for women who get frequent C. trachomatis infections. Such therapies might include probiotics and other interventions to the vaginal microbiota in order to restore a healthy, acidic, lactobacilli dominant environment.

Conclusions

Our results give further support to the hypothesis that some members of the genital microbiota, such as Prevotella, are able to produce indole and this might influence the natural course of C. trachomatis infection in women, by providing a substrate for the Chlamydia to produce tryptophan, which enables them to escape the host’s IFN-γ-mediated immune response. We demonstrated that supernatants from indole-producing bacteria were efficient in assisting the recovery of the Chlamydia after tryptophan starvation in vitro, in comparison to non-indole producers. By directly testing vaginal secretions from a range of women, we found that higher levels of indole in the vaginal secretions from some women contributed to the recovery of tryptophan-starved C. trachomatis culture in vitro. Thus for the first time we have provided ex vivo evidence that indole production in the vagina might have a key role in the outcome of genital Chlamydia infections and could lead to the development of novel therapies.

Abbreviations

- AB:

-

Aberrant bodies

- BHI:

-

Brain heart infusion

- BV:

-

Bacterial vaginosis

- EB:

-

Elementary body

- FCS:

-

Fetal calf serum

- IDO1:

-

Indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase

- IFN-γ:

-

Interferon-gamma

- IFU:

-

Inclusion forming unit

- MOI:

-

Multiplicity of infection

- PBS:

-

Phosphate-buffered saline

- PI:

-

Post infection

- PID:

-

Pelvic inflammatory disease

- RB:

-

Reticulate body

References

Abdelrahman YM, Belland RJ. The chlamydial developmental cycle. FEMS Microbiol Rev. 2005;29:949–59.

Mouldert JW. Interaction of chlamydiae and host cells in vitro. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 1991;55:143–90.

Miyairi I, Mahdi OS, Ouellette SP, Belland RJ, Byrne GI. Different growth rates of Chlamydia trachomatis biovars reflect pathotype. J Infect Dis. 2006;194:350–7.

Coles AM, Reynolds DJ, Harper A, Devitt A, Pearce JH. Low-nutrient induction of abnormal chlamydial development: A novel component of chlamydial pathogenesis? FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1993;106:193–200.

Harper A, Pogson CI, Jones ML. Chlamydial development is adversely affected by minor changes in amino acid supply, blood plasma amino acid levels, and glucose deprivation. Infect Immun. 2000;68:1457–64.

Beatty WL, Byrne GI, Morrisontt RP. Morphologic and antigenic characterization of interferon γ-mediated persistent Chiamydia trachomatis infection in vitro. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1993;90:3998–4002.

Wyrick PB. Chlamydia trachomatis persistence in vitro – An overview. J Infect Dis. 2010;201:S88–95.

Ong VA, Marsh JW, Lawrence A, Allan JA, Timms P, Huston WM. The protease inhibitor JO146 demonstrates a critical role for CtHtrA for Chlamydia trachomatis reversion from penicillin persistence. Front Cell Infect Microbiol. 2013;3:100.

Chacko A, Barker CJ, Beagley KW, Hodson MP, Plan MR, Timms P, et al. Increased sensitivity to tryptophan bioavailability is a positive adaptation by the human strains of Chlamydia pneumoniae. Mol Microbiol. 2014;93:797–813.

Newman L, Rowley J, Vander Hoorn S, Wijesooriya NS, Unemo M, Low N, et al. Global estimates of the prevalence and incidence of four curable sexually transmitted Infections in 2012 based on systematic review and global reporting. PLoS ONE. 2015;10:12.

Hafner LM, Pelzer ES. Tubal damage, infertility and tubal ectopic pregnancy: Chlamydia trachomatis and other microbial aetiologies. Ectopic Pregnancy. 2011;1194–212. doi:10.5772/21555.

Kimani J, Maclean IW, Bwayo JJ, Macdonald K, Oyugi J, Maitha GM, et al. Risk factors for Chlamydia trachomatis pelvic inflammatory disease among sex workers in Nairobi, Kenya. J Infect Dis. 1996;173:1437–44.

Hillis SD, Owens LM. Marchbanks P a, Amsterdam LF, Mac Kenzie WR. Recurrent chlamydial infections increase the risks of hospitalization for ectopic pregnancy and pelvic inflammatory disease. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1997;176:103–7.

Oakeshott P, Kerry S, Aghaizu A, Atherton H, Hay S, Taylor-robinson D, et al. Randomised controlled trial of screening for Chlamydia trachomatis to prevent pelvic inflammatory disease: the POPI (prevention of pelvic infection) trial. BMJ. 2010;340:c1642.

Hafner LM, Collet TA, Hickey DK. Immune regulation of Chlamydia trachomatis infections of the female genital tract. Immune Response Act. 2014;177–225. DOI: 10.5772/57542.

Menon S, Timms P, Allan JA, Alexander K, Rombauts L, Horner P, et al. Human and pathogen factors associated with Chlamydia trachomatis. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2015;28:969–85.

Zhang J. Yin and yang interplay of IFN- γ in inflammation and autoimmune disease. J Clin Invest. 2007;117:9–11.

Hook CE, Telyatnikova N, Goodall JC, Braud VM, Carmichael AJ, Wills MR, et al. Effects of Chlamydia trachomatis infection on the expression of natural killer (NK) cell ligands and susceptibility to NK cell lysis. Clin Exp Immunol. 2004;138:54–60.

O’Meara CP, Armitage CW, Harvie MC, Andrew DW, Timms P, Lycke NY, et al. Immunity against a Chlamydia infection and disease may be determined by a balance of IL-17 signaling. Immunol Cell Biol. 2014;92:287–97.

Barral R, Desai R, Zheng X, Frazer LC, Sucato GS, Haggerty CL, et al. Frequency of Chlamydia trachomatis-specific T cell interferon-γ and interleukin-17 responses in CD4-enriched peripheral blood mononuclear cells of sexually active adolescent females. J Reprod Immunol. 2014;103:29–37.

Chen W. IDO : more than an enzyme. Nat Immunol. 2011;12:809–11.

Leonhardt RM, Lee S, Kavathas PB, Cresswell P. Severe tryptophan starvation blocks onset of conventional persistence and reduces reactivation of Chlamydia trachomatis. Infect Immun. 2007;75:5105–17.

Lewis ME, Belland RJ, AbdelRahman YM, Beatty WL, Aiyar A a, Zea AH, et al. Morphologic and molecular evaluation of Chlamydia trachomatis growth in human endocervix reveals distinct growth patterns. Front Cell Infect Microbiol. 2014;4:71.

Aiyar A, Quayle AJ, Buckner LR, Sherchand SP, Chang TL, Zea AH, et al. Influence of the tryptophan-indole-IFNγ axis on human genital Chlamydia trachomatis infection: role of vaginal co-infections. Front Cell Infect Microbiol. 2014;4:72.

Belland RJ, Nelson DE, Virok D, Crane DD, Hogan D, Sturdevant D, et al. Transcriptome analysis of chlamydial growth during IFN-gamma-mediated persistence and reactivation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:15971–6.

Morrison RP. Differential sensitivities of Chlamydia trachomatis strains to inhibitory effects of gamma Interferon. Infect Immun. 2000;68:6038–40.

Caldwell HD, Wood H, Crane D, Bailey R, Jones RB, Mabey D, et al. Polymorphisms in Chlamydia trachomatis tryptophan synthase genes differentiate between genital and ocular isolates. J Clin Invest. 2003;111:1757–69.

Nelson DE, Virok DP, Wood H, Roshick C, Johnson RM, Whitmire WM, et al. Chlamydial IFN-γ immune evasion is linked to host infection tropism. PNAS. 2005;102:10658–63.

Wood H, Fehlner-Gardner C, Berry J, Fischer E, Graham B, Hackstadt T, et al. Regulation of tryptophan synthase gene expression in Chlamydia trachomatis. Mol Microbiol. 2003;49:1347–59.

Carlson JH, Wood H, Roshick C, Caldwell HD, McClarty G. In vivo and in vitro studies of Chlamydia trachomatis TrpR:DNA interactions. Mol Microbiol. 2006;59:1678–91.

Darville T. Pelvic inflammatory disease: identifying research gaps-proceedings of a workshop sponsored by Department of Health and Human Services/National Institutes of Health/National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, November 3–4, 2011. Sex Transm Dis. 2013;40:761–7.

Martin HL, Richardson BA, Nyange PM, Lavreys L, Hillier SL, Chohan B, et al. Vaginal lactobacilli, microbial flora, and risk of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 and sexually transmitted disease acquisition. J Infect Dis. 1999;180:1863–8.

Brotman RM, Klebanoff M a, Nansel TR, Yu KF, Andrews WW, Zhang J, et al. Bacterial vaginosis assessed by gram stain and diminished colonization resistance to incident gonococcal, chlamydial, and trichomonal genital infection. J Infect Dis. 2010;202:1907–15.

Schwebke JR, Desmond R. A randomized trial of metronidazole in asymptomatic bacterial vaginosis to prevent the acquisition of sexually transmitted diseases. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2007;196:517.e1–6.

Morrison RP. New insights into a persistent problem — chlamydial infections. J Clin Invest. 2003;11:1647–9.

Ziklo N, Huston WM, Hocking JS, Timms P. Chlamydia trachomatis genital tract infections: When host immune response and the microbiome collide. Trends Microbiol. 2016;24:750–65.

Fehlner-Gardiner C, Roshick C, Carlson JH, Hughes S, Belland RJ, Caldwell HD, et al. Molecular basis defining human Chlamydia trachomatis tissue tropism. A possible role for tryptophan synthase. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:26893–903.

Huston WM, Theodoropoulos C, Mathews S a, Timms P. Chlamydia trachomatis responds to heat shock, penicillin induced persistence, and IFN-gamma persistence by altering levels of the extracytoplasmic stress response protease HtrA. BMC Microbiol. 2008;8:190.

Huston WM, Swedberg JE, Harris JM, Walsh TP, Mathews SA, Timms P. The temperature activated HtrA protease from pathogen Chlamydia trachomatis acts as both a chaperone and protease at 37 C. FEBS Lett. 2007;581:3382–6.

Whiley DM, Sloots TP. Comparison of three in-house multiplex PCR assays for the detection of Neisseria gonorrhoeae and Chlamydia trachomatis using real-time and conventional detection methodologies. Pathology. 2005;37:364–70.

Kozlowski PA, Lynch RM, Patterson RR, Cu-Uvin S, Flanigan TP, Neutra MR. Modified wick method using weck-cel sponges for collection of human rectal secretions and analysis of mucosal HIV antibody. JAIDS. 2000;24:297–309.

Salkowski E. Ueber das Verhalten der Skatolcarbonsäure im Organismus. Zeitschrift für Physiol Chemie. 1885;9:23–33. doi:10.1515/bchm1.1885.9.1.23.

Szkop M, Sikora P, Orzechowski S. A novel, simple, and sensitive colorimetric method to determine aromatic amino acid aminotransferase activity using the Salkowski reagent. Folia Microbiol. 2012;57:1–4.

Geisler WM, Wang C, Morrison SG, Black CM, Bandea CI, Hook EW. The natural history of untreated Chlamydia trachomatis infection in the interval between screening and returning for treatment. Sex Transm Dis. 2008;35:119–23.

Geisler WM. Duration of untreated, uncomplicated Chlamydia trachomatis genital infection and factors associated with Chlamydia resolution: a review of human studies. J Infect Dis. 2010;201(Suppl):S104–13.

Walker J, Tabrizi SN, Fairley CK, Chen MY, Bradshaw CS, Twin J, et al. Chlamydia trachomatis incidence and re-infection among young women--behavioural and microbiological characteristics. PLoS ONE. 2012;7:e37778.

Hafner L, Beagley K, Timms P. Chlamydia trachomatis infection: host immune responses and potential vaccines. Mucosal Immunol. 2008;1:116–30.

Doerflinger SY, Throop AL, Herbst-Kralovetz MM. Bacteria in the vaginal microbiome alter the innate immune response and barrier properties of the human vaginal epithelia in a species-specific manner. J Infect Dis. 2014;209:1989–99.

Brotman RM. Vaginal microbiome and sexually transmitted infections: an epidemiologic perspective. J Clin Invest. 2011;121:4610–7.

Mirmonsef P, Hotton AL, Gilbert D, Burgad D, Landay A, Weber KM, et al. Free glycogen in vaginal fluids is associated with Lactobacillus colonization and low vaginal pH. PLoS ONE. 2014;9:e102467.

Gong Z, Luna Y, Yu P, Fan H. Lactobacilli inactivate Chlamydia trachomatis through lactic acid but not H2O2. PLoS ONE. 2014;9:e107758.

Kaewsrichan J, Peeyananjarassri K, Kongprasertkit J. Selection and identification of anaerobic lactobacilli producing inhibitory compounds against vaginal pathogens. FEMS Immunol Med Microbiol. 2006;48:75–83.

Aroutcheva A, Gariti D, Simon M, Shott S, Faro J, Simoes J a, et al. Defense factors of vaginal lactobacilli. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2001;185:375–9.

Ravel J, Gajer P, Abdo Z, Schneider GM, Koenig SSK, McCulle SL, et al. Vaginal microbiome of reproductive-age women. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108 Suppl:4680–7.

Cherpes TL, Meyn L a, Krohn M a, Lurie JG, Hillier SL. Association between acquisition of herpes simplex virus type 2 in women and bacterial vaginosis. Clin Infect Dis. 2003;37:319–25.

Wiesenfeld HC, Hillier SL, Krohn MA, Landers DV, Sweet RL. Bacterial vaginosis is a strong predictor of Neisseria gonorrhoeae and Chlamydia trachomatis infection. Clin Infect Dis. 2003;36:663–8.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Vanissa Ong and Dr. Anu Chacko for their contributions to the Chlamydia cell culture work. We thank the Nambour Sexual Health Clinic staff, especially Daveena Hodgson and Sharon Young. This research study was supported by the Wish List SCHHS/USC Grants Scheme.

Funding

Wishlist Foundation, Australia. No contribution was made from this foundation body to the study design, specimens collection, analysis, interpretation of the data or writing the manuscript.

Authors’ contribution

NZ collected the participants’ samples, analyzed and interpreted the patient data. In addition, NZ preformed all the in vitro experiments, analyzed and interpreted the data, and wrote the manuscript. WH was a major contributor to the in vitro experiment design, and interpretation of the data including statistics analysis. WH was a major contributor in writing and reviewing the manuscript. KT is the sexual clinic director. Coordinating the samples collection in the women Chlamydia trial. MK was a major contributor to the microbiology work with anaerobic Prevotella strains, providing the materials and the lab equipment. Was a contributor to the biochemical work to quantify indole concentrations from patient’s secretions and interpretation of this data. PT collaborated the clinical trial with the clinic, provided the funds necessary for the project, provided guidance to the project design, and data interpretation. PT was a major contributor in writing and reviewing the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Human Research Ethics Committee reviewed and provided full approval for the study: The Prince Charles Hospital Human Research Ethics committee number HREC/14/QPCH/14, ethics approval number A/14/623. All participants provided informed written consent to participate in the study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional files

Additional file 1: Figure S1.

Microscopic recovery of C. trachomatis D following tryptophan starvation and recovery. (DOCX 494 kb)

Additional file 2: Figure S2.

Recovery of tryptophan-starved C. trachomatis strain D after rescue with secretions from five (Chlamydia positive/negative) participants that have different concentrations of indole in their vaginal secretions. (DOCX 61 kb)

Additional file 3: Figure S3.

Recovery of tryptophan-starved C. trachomatis strain D after rescue with supernatant from indole positive/indole negative bacteria. (DOCX 248 kb)

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Ziklo, N., Huston, W.M., Taing, K. et al. In vitro rescue of genital strains of Chlamydia trachomatis from interferon-γ and tryptophan depletion with indole-positive, but not indole-negative Prevotella spp. . BMC Microbiol 16, 286 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12866-016-0903-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12866-016-0903-4