Abstract

Background

TRIANGULAR HULL1 (TH1), a member of the rice ALOG gene family, has been characterized as a rice lemma/palea-related gene. To understand the gene regulatory network that controlled by TH1, we analyzed the transcriptome from a TH1 knock out (KO) line, which was generated by CRISPR/Cas9. Our study may shed some light on the molecular mechanism of lemma/palea development.

Results

We obtained 20 T0 th1-C transgenic plants by CRISPR/Cas9. Among the 20 plants, there were eight bi-allelic mutations, five homozygous mutations, three heterozygous mutations, and four Non-KO plants. By comparing with the wild type and the heterozygous knock out (KO) line, the homozygous KO lines showed defects in lemma/palea development as well as in grain filling. Further more, we studied the gene regulatory network that controlled by TH1 by comparing the transcriptome of a homozygous TH1 KO line with its Non-KO line as a control. A total of 622 genes were identified as differentially expressed genes (DEGs), of which 297 genes were significantly up-regulated while 325 genes were down-regulated. One hundred thirty eight of the DEGs were assigned to the 59 KEGG (Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes) pathways. Among these annotated DEGs, 15 genes were related to plant hormone signal transduction, eight genes were related to starch and sucrose metabolism. These were the two largest groups of DEGs according to the KEGG pathway analysis.

Conclusions

Our results indicated that hormone related genes and starch/sucrose metabolism related genes might act as downstream targets of TH1; they might be responsible for lemma/palea development and grain filling respectively.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Rice (Oryza sativa L.) is one of the most important crops, feeding more than one third of the whole population of the world. The spikelet is a critical unit for rice yield. In rice, one spikelet contains a fertile floret, which consists by one lemma, one palea, two lodicules, six stamens and one pistil. The shape of the grain is largely determined by the development of the lemma and palea. In recent years, a number of genes involved in lemma and palea development have been identified.

DROOPING LEAF (DL), a member of the YABBY gene family, is specifically expressed in the lemma, but not in the palea, it involves in leaf midrib formation and carpel specification. Although its expression is restricted to the lemma, its function on lemma development remains unknown (Yamaguchi et al. 2004; Ishikawa et al. 2009); MOSAIC FLORAL ORGANS1 (MFO1)/MADS6 is a member of MADS-box gene family that specifies palea identity. In the mfo1 mutants, the margin of the palea shows an abnormal outgrowth accompanied by an ectopic expression of DL (Ohmori et al. 2009; Li et al. 2010); RETARDED PALEA1 (REP1), a TCP-domain protein, is expressed specifically at an early stage in the palea primordial, and later disperses to the lemma, palea and stamen. Transgenic plants overexpressing REP1 show a similar phenotype to that of mfo1 (Luo et al. 2005; Yuan et al. 2009); OsMADS1/LHS1 and OsMADS15 play a critical role in lemma and palea development, loss of function in these two genes causes defects in both lemma and palea development (Jeon et al. 2000; Wang et al. 2010). PEN BEAK (OPB)/STAMENLESS1 (SL1)/JAG/ and DEGENERATED HULL1 (DH1) are also required for normal lemma/palea development (Horigome et al. 2009; Xiao et al. 2009; Duan et al. 2010; Li et al. 2008). Recently research showed that genes involved in the small RNA pathway including SHOOT ORGANIZATION1 (SHO1), SHOOTLESS2 (SHL2), SHO2/SHOOTLESS4 (SHL4) and WAVY LEAF1 (WAF1) participate in determining the polarity of the lemma and palea (Itoh et al. 2000; Nagasaki et al. 2007; Abe et al. 2010) .

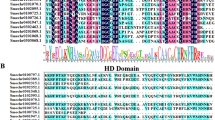

TRIANGULAR HULL1 (TH1), also known as BEAK LIKE SPIKELET1 (BLS1)/BEAK-SHAPED GRAIN1 (BSG1)/BEAK-SHAPED HULL1 (BH1)/ABNORMAL FLOWER AND DWARF1 (AFD1), is a member of the rice ALOG gene family, it encodes a DUF640 domain transcription factor that associated with grain shape (Iyer and Aravind 2011), and it is expressed mainly in the young panicle and elongating stem. In comparison with the wild type plant, th1 mutant shows an abnormal beak-shaped grain whose lemma and palea develop incompletely, resulting in the reduction for grain width, and therefore for the yield (Li et al. 2012; Ma et al. 2013; Yan et al. 2013; Wei et al. 2013; Ren et al. 2016). Although TH1 has been proven to play an important role in lemma/palea development, the regulatory network of TH1 still remains largely unknown. In the previous research, the mutant lines using for TH1 characterization were with amino acid change (bsg1–2) (Yan et al. 2013), a frame shift that distant from the translation initiation site (th1–1, bsg1–1 and afd1) (Li et al. 2012; Yan et al. 2013; Ren et al. 2016) or large fragment deletion (~ 50 kb deletion for bls1 and ~ 55 kb deletion for bh1) (Ma et al. 2013; Wei et al. 2013). In this study, we developed a TH1 KO line by CRISPR/Cas9 and explored the transcriptional regulatory network controlled by TH1.

Result

TH1 KO line was generated using CRISPR/Cas9

To investigate the biological function of TH1, we generated a TH1 KO line th1-C by CRISPR/Cas9, with the target site located within the gene at approximately 55 bp downstream of the translation initiation site (Fig. 1a). We obtained 20 T0 th1-C transgenic plants and analyzed the target site in all the plants (Additional file 1: Table S1). Direct Sanger-sequencing of the target-containing amplicons followed by decoding via DsDecodeM (Liu et al. 2015) showed that among the 20 plants, there were eight bi-allelic mutations, five homozygous mutations, three heterozygous mutations, and four Non-KO plants. Based on allelic mutation types, 15.0% (6/40) of the mutations were nucleotide deletions, while 57.5% (23/40) of the mutations were nucleotide insertions, all of which were 1 bp single insertion (Table 1).

The CRISPR/Cas9 target site of TH1 and phenotype of the KO plants. a Schematic of TH1 gene structure and the CRISPR/Cas9 target site. TH1 contains a single exon indicated by gray rectangles. The translation initiation codon (ATG) and termination codon (TGA) are shown. The target site nucleotides are shown in capital letters, and the protospacer adjacent motif (PAM) site is underlined. b, c Panicles of wild type and KO plant. d-f spikelet of wild type and KO plant. g, h Pollen viability test for wild type and KO plant, represents the pollen activity for 3 biological replicates of each line respectively. i Statistical data of pollen activity. Values are shown as means ± s.d. (n = 3). P values were calculated by the Student’s t-test. Scale bar is 5 cm in (b) and (c), 2 mm in (d), e and (f), 200 μm in (g) and (h)

Homozygous TH1 KO lines showed defects in lemma/Palea development

During the vegetative growth stage, no phenotypic change could be observed in the T0 plants of th1-C. Whereas during the reproductive growth stage, by comparing with the wild type and the heterozygous KO line, the homozygous KO lines showed a slender lemma/palea, which displayed a beak-like structure. In addition, unlike those of the wild type plants, the filaments of the KO plants were curled (Fig. 1b-f). In the maturing stage, the homozygous KO lines had a defect in grain filling and were completely infertile. By iodine potassium iodide staining, the pollen activity between homozygous KO line and wild type plant showed no significant difference (Fig. 1g-i). This result indicated that the sterility of the homozygous KO plant might not relate to pollen activity. We also generated a TH1 overexpression transgenic line, however, no phenotypic change could be observed during the whole developmental stages when compared with the wild type (data not show).

T1 homozygous KO plants were identified for the subsequent RNA-seq

In order to study the gene regulatory network that controlled by TH1, we analyzed the transcriptome data generated from the young panicle (~ 2 cm) of homozygous th1-C and Non-KO control plants. Since the T0 generation of homozygous KO plants were infertile, T1 homozygous KO plants (with 1 bp deletion) and Non-KO plants that derived from a T0 heterozygous KO plant (th1-C-15) were used for the RNA-seq experiment. By comparing with the Non-KO plant, the homozygous KO plant with 1 bp deletion in the target site leads to a frame shift with premature transcription termination for TH1 (Fig. 2a-b). By qRT-PCR, we detected no significant difference for TH1 expression level between KO and Non-KO plants (Fig. 2c).

Comparation of TH1 locus between KO and Non-KO lines. a Genomic structures at the TH1 locus in KO and Non-KO line. Arrows indicate the qRT-PCR primers for TH1. b The original sequencing chromatograms of the target site for TH1 in Non-KO and homozygous KO line, which were derived from a T0 heterozygous KO plant. The protospacer adjacent motif (PAM) site is underlined, the “C” marked with an asterisk was the deleted in the KO plant. c Expression level of TH1 in KO and Non-KO line. Values are shown as means ± s.d. (n = 3). P values were calculated by the Student’s t-test

Transcriptome analysis

We carried out the RNA-seq with three biological replicates for KO and Non-KO samples respectively. After filtering, the total number of clean reads per library was 41.16, 46.05 and 44.08 million for KO while 50.45, 43.21 and 45.24 million for Non-KO. For each library, at least 91.82% of the clean reads had a quality score of Q30. The GC content was 51.75%, 51.82% and 52.15% for KO while 51.35%, 51.22% and 51.66% for Non-KO. More than 83.53% of the clean reads were successfully and uniquely mapped to the rice genome using the TopHat2 software (Table 2) (Kim et al. 2013). Additionally, Spearman correlation coefficients between any two replicates were calculated using deepTool2 (Ramírez et al. 2016). The correlation was higher within groups than that between KO and Non-KO samples (Fig. 3a). Taken together, these results indicated the good quality of the sequencing data, suggesting the reliability for subsequent transcriptome analysis results.

Overview of the DEGs. a Correlation between any two replicates was calculated by Spearman Correlation Coefficient value. b Numbers of up-regulated and down-regulated DEGs. c KEGG pathway assignment of the assembled unigenes (top 50 pathways according to enrichment factor). The vertical axis represents the enriched KEGG pathways and the horizontal axis represents the number of unigenes in each pathway

Twenty-two thousand seven hundred ninety-seven genes expression level could be detected by RNA-seq at least in one group of the samples (Additional file 2: Table S2). Among these genes, a total of 622 genes were identified as differentially expressed genes (DEGs) with the cut-off for FDR (False Discovery Rate) < 0.05 and FC (Fold Change) ≥ 2. Of these DEGs, 297 genes were significantly up-regulated while 325 genes were down-regulated (Fig. 3b; Additional file 3: Table S3). One hundred fifty DEGs were annotated by KEGG (Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes) (Additional file 4: Table S4). One hundred thirty-eight of 150 DEGs were assigned to the 59 KEGG pathways (Additional file 5: Table S5). Among these KEGG pathway annotated DEGs, 15 genes were related to plant hormone signal transduction, and eight genes were related to starch and sucrose metabolism. These were the two largest groups of DEGs according to the KEGG pathway analysis (Fig. 3c). To further validate the expression profiles of genes in our RNA-seq analyses, 15 genes were selected for expression quantification using qRT-PCR, including five that had been previously characterized as lemma/palea-related genes but did not show differential expression in our experiment (WAF1, OsMADS15, SHO1, MFO1 and LHS) and 10 DEGs that were mainly related to plant hormone signal transduction (RERJ1, Os06g0142400, OsJAZ12, OsJAZ11, OsJAZ10, OsJAZ8, OsJAZ7, OsEIL2, OsSAUR23 and OsSAUR20). The results revealed that the expression pattern of the selected genes as determined by qRT-PCR were largely identical to those determined by RNA-seq (Additional file 6: Figure S1).

Discussion

TH1 is critical for the rice fertility

TH1 has been cloned by five individual research groups using different mutants within different genetic backgrounds respectively. All these previous studies have shown that, TH1 played an important role in lemma and palea development as well as rice fertility. Although both the amino acid change (bsg1–2) (Yan et al. 2013) and frame shift (th1–1, bsg1–1 and afd1) (Li et al. 2012; Yan et al. 2013; Ren et al. 2016) mutants showed a reduction of seed setting rate, they were still partially fertile. In our study, we generated a TH1 KO line using CRISPR/Cas9, with the target site relatively close to the translation initiation site. This difference may be responsible for the infertility of th1-C while all the other mutations were partially fertile with the mutant site relatively far away from the translation initiation site. Our result was also consistent with the fact that the transgenic plants of pTH1-RNAi had no filled seed (Li et al. 2012). In our RNA-seq experiment, eight genes related to starch and sucrose metabolism were differentially expressed between KO and Non-KO plants (Fig. 4), the altered expression levels of these genes might result in the defection for grain filling in the homozygous KO line.

Heat map of starch/sucrose metabolism related genes and plant hormone signal transduction related genes. The red color in this figure denotes a high level of expression while blue indicates low expression. Non-KO_REP1, Non-KO_REP2, and Non-KO_REP3 denote the three control biological replicates, while KO_REP1, KO_REP2, and KO_REP3 denote the three biological replicates for the TH1 KO line. The expression levels for each gene are shown in the heat maps using FPKM (Fragments Per Kilobase of transcript per Million fragments mapped) with a log2 scale

Plant hormone-related genes might act as downstream targets of TH1 and involve in lemma/Palea development

It has been proved that DL, MFO1/MADS6, REP1, OsMADS1/LHS, OsMADS15, OPB/SL1/JAG/DH1, SHO1, SHL2, SHO2/SHL4 and WAF1 are involved in lemma/palea development (Yamaguchi et al. 2004; Ishikawa et al. 2009; Ohmori et al. 2009; Li et al. 2010; Ohmori et al. 2009; Li et al. 2010; Luo et al. 2005; Yuan et al. 2009; Horigome et al. 2009; Xiao et al. 2009; Duan et al. 2010; Li et al. 2008; Itoh et al.; Nagasaki et al. 2007; Abe et al. 2010), however, the expression levels of these genes did not show significant difference between KO and Non-KO lines in our experiment (Additional file 7: Figure S2). We further compared the expression levels of these 10 genes between KO lines and Non-CRISPR treated Nipponbare plants, the qRT-PCR results were in accordance with the RNA-seq data (FC < 2) (Fig. 5a-j).

Expression levels of known lemma/palea related genes. 10 previous known lemma/palea related genes expression profiles in KO and Non-CRISPR treated Nipponbare. a DL, b MFO1/MADS6, c REP1, d OsMADS1/LHS, e OsMADS15, f OPB/SL1/JAG/DH1, g SHO1, h SHL2, i SHO2/SHL4 and (j) WAF1. Values are shown as means ± s.d. (n = 3)

Some of these genes’ expression pattern within TH1 mutant background had been studied in the previous research: In lemma and palea of afd1, MFO1/OsMADS6 seemed to be close to that of wild type. In lodicules, OsMADS1/LHS, and OsMADS15 transcripts were expressed in the mutants but not in wild type (Lou et al. 2016); In the bh1 mutant, OsMADS1/LHS, OsMADS15, REP1 and DL showed a down-regulation in the mutant around anthesis, however, they did not specify the developmental stage for the samples (Wei et al. 2013); The expression levels of OsMADS1/LHS and MFO1/OsMADS6 were only down-regulated in 0.5-cm young panicles, but not in 8-cm young panicles for the bsg1–1 mutant when comparing with the wild type (Yan et al. 2013); For the 1-cm young panicle, OsMADS1/LHS, MFO1/OsMADS6, OsMADS15, REP1 and DL showed no significant difference between bls1 and wild type (Ma et al. 2013), this is consistent with our finding from the RNA-seq data. Taken these together, it indicated that expression profile of these genes might be largely different in different genetic backgrounds, different tissues or different developmental stages.

We identified 622 DEGs related to TH1, and among these DEGs, a subset of genes (15 in total) related to plant hormone signal transduction was enriched (Fig. 4). Previous research has revealed that the plant hormone jasmonic acid (JA) plays an important role in determining rice spikelet morphogenesis. By repressing OsMYC2, a JA-inducible transcription factor would activate OsMADS1, an E-class gene crucial to spikelet development (Cai et al. 2014). In our experiment, OsMYC2 showed a significant expression change. In addition, a group of jasmonate ZIM-domain protein genes showed a differential expression between the homozygous KO plants and the Non-KO plants, including OsJAZ6, OsJAZ7, OsJAZ8, OsJAZ10, OsJAZ11 and OsJAZ12 (Ye et al. 2009). In addition to this, five auxin-related genes (OsIAA2, OsSAUR12, OsSAUR20, OsSAUR23, OsSAUR25) (Song et al. 2009; Jain et al. 2006), two ethylene-related genes (OsEIL2, Os03g0324200) (Yang et al. 2015) and one ABA (abscisic acid) receptor gene (OsPLY4) (He et al. 2014) expressed differentially between KO and Non-KO lines. This result implied that these genes might act as downstream targets of the rice transcription factor TH1 and be involved in rice lemma/palea development.

Conclusions

TH1 was characterized as a transcription factor belonging to the ALOG gene family. Loss of function in TH1 led to defects for rice lemma and palea development as well as defects for grain filling. Our transcriptome study provided a survey for the regulatory network that controlled by TH1. The results indicated that hormone related genes and starch/sucrose metabolism related genes might act as downstream targets of TH1; they might be responsible for lemma/palea development and grain filling respectively. Most of these genes are uncharacterized or known to have other functions. Although RNA-seq provided the possibility of discovering new lemma/palea related or grain filling related genes, further research such as KO or overexpress of these genes will be needed to confirm our hypothesis.

Methods

Plant materials and growth conditions

Rice (Oryza sativa L.) plants were grown in the greenhouse at 30 °C for days and 25 °C for night. The genetic background of the all the transgenic plants was Nipponbare. For the RNA-seq experiment, the homozygous TH1 knock out line and its control Non-KO line were derived from a T0 heterozygous TH1 knock out plant: th1-C-15. For each progeny of th1-C-15, we sequenced the target site. The plants harboring two alleles of mutation were referred as homozygous KO line while plants carrying homozygous intact-TH1 gene were used as control and referred as Non-KO line.

Vector construction

To knock out TH1: Target site was designed online (http://cbi.hzau.edu.cn/crispr/), the optimal target site with low off-target score and high sgRNA score was selected. To prepare CRISPR/Cas9 binary constructs, the OsU3 sgRNA vector was used as template to generate a target-sgRNA expression cassette(s) using an overlapping PCR method, then the target-sgRNA was constructed to pYLCRISPR/Cas9-MH using a Golden Gate ligation methods. All the primers were showed in Additional file 8: Table S6.

To overexpress TH1: The open reading frame of TH1 (without stop codon) was amplified from cDNA using primers Oeth1F and Oeth1R. The fragment was digested by BamHI and SmaI, and then cloned into pCAMBIA1300/35S:GFP. The primers were showed in Additional file 8: Table S6.

Sample collection and RNA extraction

Young panicle (panicle length: ~ 2 cm) from a single plant was collected, total RNA was extracted using a Plant RNA Purification Kit: RNeasy Plant Mini Kit (74,904, QIAGEN, Germany) following the manufacturer’s instructions. RNA degradation and contamination were monitored on 1% agarose gels.

Library construction and Illumina sequencing

Library construction and RNA-seq were performed at Beijing BioMarker Technologies (Beijing, China) in accordance with the institute’s protocols and briefly described here. RNA concentration was measured using NanoDrop 2000 (Thermo). RNA integrity was assessed using the RNA Nano 6000 Assay Kit of the Agilent Bioanalyzer 2100 system (Agilent Technologies, CA, USA). A total amount of 1 μg RNA per sample was used as input material for the RNA sample preparations. Sequencing libraries were generated using NEBNext UltraTM RNA Library Prep Kit for Illumina (NEB, USA) following manufacturer’s recommendations and index codes were added to attribute sequences to each sample. Briefly, mRNA was purified from total RNA using poly-T oligo-attached magnetic beads. Fragmentation was carried out using divalent cations under elevated temperature in NEBNext First Strand Synthesis Reaction Buffer (5X). First strand cDNA was synthesized using random hexamer primer and M-MuLV Reverse Transcriptase. Second strand cDNA synthesis was subsequently performed using DNA Polymerase I and RNaseH. Remaining overhangs were converted into blunt ends via exonuclease/polymerase activities. After adenylation of 3′ ends of DNA fragments, NEBNext Adaptor with hairpin loop structure were ligated to prepare for hybridization. In order to select cDNA fragments of preferentially 240 bp in length, the library fragments were purified with AMPure XP system (Beckman Coulter, Beverly, USA). Then 3 μl USER Enzyme (NEB, USA) was used with size-selected, adaptor-ligated cDNA at 37 °C for 15 min followed by 5 min at 95 °C before PCR. Then PCR was performed with Phusion High-Fidelity DNA polymerase, Universal PCR primers and Index (X) Primer. At last, PCR products were purified (AMPure XP system) and library quality was assessed on the Agilent Bioanalyzer 2100 system. The clustering of the index-coded samples was performed on a cBot Cluster Generation System using TruSeq PE Cluster Kit v4-cBot-HS (Illumina) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. After cluster generation, the library preparations were sequenced on Illumina Hiseq Xten PE150 platform (paired end 150 bp) and paired-end reads were generated. All the raw data have been submitted to the NCBI SRA database under accession number of PRJNA470824.

RNA-seq data analysis

Raw data (raw reads) of fastq format were firstly processed through in-house perl scripts. In this step, clean data (clean reads) were obtained by removing reads containing adapter, reads containing ploy-N and low-quality reads from raw data. At the same time, Q20, Q30, GC-content and sequence duplication level of the clean data were calculated. These clean reads were then mapped to the reference genome sequence (Os-Nipponbare-Reference-IRGSP-1.0: http://rapdb.dna.affrc.go.jp/download/irgsp1.html). Only reads with a perfect match or one mismatch were further analyzed and annotated based on the reference genome. Tophat2 tools soft were used to map with reference genome (Kim et al. 2013). Gene function was annotated based on the following databases: Nr (NCBI non-redundant protein sequences); Nt (NCBI non-redundant nucleotide sequences); Pfam (Protein family); KOG/COG (Clusters of Orthologous Groups of proteins); Swiss-Prot (A manually annotated and reviewed protein sequence database); KO (KEGG Ortholog database); GO (Gene Ontology). Differential expression analysis of two groups (KO samples and Non-KO samples) was performed using the edgeR package. edgeR is designed for the analysis of replicated count-based expression data. In principle, edgeR will combine three KO lines and compared to the combination of three Non-KO lines. Genes with FDR (false discovery rate) < 0.05 & FC (Fold Change) were assigned as differentially expressed.

Gene expression, KEGG pathway enrichment analysis

KEGG pathway enrichment analysis (http://www.genome.jp/kegg/) was performed to identify differentially expressed genes (DEGs). KOBAS (Mao et al. 2005) software was used to test the statistical enrichment of differential expression genes in KEGG pathways (E ≤ 1e-5). Gene expression levels were estimated by FPKM values (Fragments Per Kilobase of transcript per Million fragments mapped).

qRT-PCR

First-strand cDNA was synthesized from 1 μg total RNA using the PrimeScript™ RT reagent Kit (with gDNA Eraser) (RR047A, Takara, Japan) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. qRT-PCR were carried out using the ChamQTM SYBR® qPCR Master Mix (Q311–01, Vazyme, China) on the LightCycler® 480II (Roche) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Rice Ubiquitin (Os03g0234200) was used as internal reference and gene expression level was normalized to the Ubiquitin expression level. The primers were showed in Additional file 9: Table S7.

Pollen viability test

Pollen viability was estimated by IKI (iodine potassium iodide) straining. The mature pollen grains were collected from at least three unopened flowers randomly for WT and TH1 homozygous knock out plants, respectively. Then put them on a microscope slide immediately, dripped a drop of the IKI solution on the pollen and covered with a coverslip. Pollen viability counts were made 5 min after pollen was placed on an IKI solution. Pollen grains stained dark (dark red or brown color) were counted as alive.

Abbreviations

- ABA:

-

Abscisic Acid

- DEGs:

-

Differentially Expressed Genes

- FC:

-

Fold Change

- FDR:

-

False Discovery Rate

- FPKM:

-

Fragments Per Kilobase of transcript per Million fragments mapped

- GFP:

-

Green Fluorescent Protein

- JA:

-

Jasmonic Acid

- KO:

-

Knock Out

- qRT-PCR:

-

Quantitative Reverse Transcription Polymerase Chain Reaction

- WT:

-

Wild Type

References

Abe M, Yoshikawa T, Nosaka M, Sakakibara H, Sato Y, Nagato Y, Itoh J-I (2010) WAVY LEAF1, an ortholog of Arabidopsis HEN1, regulates shoot development by maintaining MicroRNA and trans-acting small interfering RNA accumulation in rice. Plant Physiol 154:1335–1346

Cai Q, Yuan Z, Chen M, Yin C, Luo Z, Zhao X, Liang W, Hu J, Zhang D (2014) Jasmonic acid regulates spikelet development in rice. Nat Commun 5:1–13

Duan Y, Diao Z, Liu H, Cai M, Wang F, Lan T, Wu W (2010) Molecular cloning and functional characterization of OsJAG gene based on a complete-deletion mutant in rice (Oryza sativa L.). Plant Mol Biol 74:605–615

He Y, Hao Q, Li W, Yan C, Yan N, Yin P (2014) Identification and characterization of ABA receptors in Oryza sativa. PLoS One 9:e95246

Horigome A, Nagasawa N, Ikeda K, Ito M, Itoh J-I, Nagato Y (2009) Rice open beak is a negative regulator of class 1 Knox genes and a positive regulator of class B floral homeotic gene. Plant J 58:724–736

Ishikawa M, Ohmori Y, Tanaka W, Hirabayashi C, Murai K, Ogihara Y, Yamaguchi T, Hirano H-Y (2009) The spatial expression patterns of DROOPING LEAF orthologs suggest a conserved function in grasses. Genes Genet Syst 84:137–146

Itoh J-I, Kitano H, Matsuoka M, Nagato Y (2000) SHOOT ORGANIZATION Genes Regulate Shoot Apical Meristem Organization and the Pattern of Leaf Primordium Initiation in Rice. Plant Cell 12:2161–2174

Iyer LM, Aravind L (2011) ALOG domains: provenance of plant homeotic and developmental regulators from the DNA-binding domain of a novel class of DIRS1-type retroposons. Biol Direct 7:39–39

Jain M, Tyagi AK, Khurana JP (2006) Genome-wide analysis, evolutionary expansion, and expression of early auxin-responsive SAUR gene family in rice (Oryza sativa). Genomics 88:360–371

Jeon JS, Jang S, Lee S, Nam J, Kim C, Lee SH, Chung YY, Kim SR, Lee YH, Cho YG et al (2000) Leafy hull sterile1 is a homeotic mutation in a rice MADS box gene affecting rice flower development. Plant Cell 12:871–884

Kim D, Pertea G, Trapnell C, Pimentel H, Kelley R, Salzberg SL (2013) TopHat2: accurate alignment of transcriptomes in the presence of insertions, deletions and gene fusions. Genome Biol 14:R36

Li A, Zhang Y, Wu X, Tang W, Wu R, Dai Z, Liu G, Zhang H, Wu C, Chen G et al (2008) DH1, a LOB domain-like protein required for glume formation in rice. Plant Mol Biol 66:491–502

Li H, Liang W, Jia R, Yin C, Zong J, Kong H, Zhang D (2010) The AGL6-like gene OsMADS6 regulates floral organ and meristem identities in rice. Cell Res 20:299–313

Li X, Sun L, Tan L, Liu F, Zhu Z, Fu Y, Sun X, Sun X, Xie D, Sun C (2012) TH1, a DUF640 domain-like gene controls lemma and Palea development in rice. Plant Mol Biol 78:351–359

Liu W, Xie X, Ma X, Li J, Chen J, Liu Y-G (2015) DSDecode: a web-based tool for decoding of sequencing chromatograms for genotyping of targeted mutations. Mol Plant 8:1431–1433

Lou S, Chen S, Zhao X, Chen L, Zhang J, Fu H, Liu Y-G, Chen Y (2016) The far-upstream regulatory region of RFL is required for its precise spatial-temporal expression for floral development in rice. Plant Mol Biol. 93:185–195 (Lou, S., Chen, S., Zhao, X. et al. Plant Mol Biol (2017) 93:185. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11103-016-0556-6)

Luo Q, Zhou K, Zhao X, Zeng Q, Xia H, Zhai W, Xu J, Wu X, Yang H, Zhu L (2005) Identification and fine mapping of a mutant gene for palealess spikelet in rice. Planta 221:222–230

Ma X, Cheng Z, Wu F, Jin M, Zhang L, Zhou F (2013) BEAK LIKE SPIKELET1 is required for lateral development of lemma and Palea in rice. Plant Mol Biol. 31:98–108 (Ma, X., Cheng, Z., Wu, F. et al. Plant Mol Biol Rep (2013) 31:98. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11105-012-0480-0)

Mao X, Cai T, Olyarchuk JG, Wei L (2005) Automated genome annotation and pathway identification using the KEGG Orthology (KO) as a controlled vocabulary. Bioinformatics 21:3787–3793

Nagasaki H, Itoh J-I, Hayashi K, Hibara K-I, Satoh-Nagasawa N, Nosaka M, Mukouhata M, Ashikari M, Kitano H, Matsuoka M et al (2007) The small interfering RNA production pathway is required for shoot meristem initiation in rice. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 104:14867–14871

Ohmori S, Kimizu M, Sugita M, Miyao A, Hirochika H, Uchida E, Nagato Y, Yoshida H (2009) MOSAIC FLORAL ORGANS1, an AGL6-like MADS box gene, regulates floral organ identity and meristem fate in Rice. Plant Cell 21:3008–3025

Ramírez F, Ryan DP, Grüning B, Bhardwaj V, Kilpert F, Richter AS, Heyne S, Dündar F, Manke T (2016) deepTools2: a next generation web server for deep-sequencing data analysis. Nucl Acids Res 44:W160–W165

Ren D, Rao Y, Wu L, Xu Q, Li Z, Yu H, Zhang Y, Leng Y, Hu J, Zhu L et al (2016) The pleiotropic ABNORMAL FLOWER AND DWARF1affects plant height, floral development and grain yield in rice. J Integr Plant Biol 58:529–539

Song Y, Wang L, Xiong L (2009) Comprehensive expression profiling analysis of OsIAA gene family in developmental processes and in response to phytohormone and stress treatments. Planta 229:577–591

Wang K, Tang D, Hong L, Xu W, Huang J, Li M, Gu M, Xue Y, CHENG Z (2010) DEP and AFO regulate reproductive habit in rice. PLoS Genet 6:e1000818

Wei X, Zhang X, Shao G, He J, Jiao G, Xie L, Sheng Z, Tang S, Hu P (2013) Fine mapping of BH1, a gene controlling lemma and Palea development in rice. Plant Cell Rep 32:1455–1463

Xiao H, Tang J, Li Y, Wang W, Li X, Jin L, Xie R, Luo H, Zhao X, Meng Z et al (2009) STAMENLESS 1, encoding a single C2H2 zinc finger protein, regulates floral organ identity in rice. Plant J 59:789–801

Yamaguchi T, Nagasawa N, Kawasaki S, Matsuoka M, Nagato Y, Hirano H-Y (2004) The YABBY gene DROOPING LEAF regulates carpel specification and midrib development in Oryza sativa. Plant Cell 16:500–509

Yan D, Zhou Y, Ye S, Zeng L, Zhang X, He Z (2013) BEAK-SHAPED GRAIN 1/TRIANGULAR HULL 1, a DUF640 gene, is associated with grain shape, size and weight in rice. Sci China Life Sci 56:275–283

Yang C, Ma B, He S-J, Xiong Q, Duan K-X, Yin C-C, Chen H, Lu X, Chen S-Y, Zhang J-S (2015) MAOHUZI6/ETHYLENE INSENSITIVE3-LIKE1 and ETHYLENE INSENSITIVE3-LIKE2 regulate ethylene response of roots and coleoptiles and negatively affect salt tolerance in Rice. Plant Physiol 169:148–165

Ye H, Du H, Tang N, Li X, Xiong L (2009) Identification and expression profiling analysis of TIFY family genes involved in stress and phytohormone responses in rice. Plant Mol Biol 71:291–305

Yuan Z, Gao S, Xue D-W, Luo D, Li L-T, Ding S-Y, Yao X, Wilson ZA, Qian Q, Zhang D-B (2009) RETARDED PALEA1 controls Palea development and floral Zygomorphy in Rice. Plant Physiol 149:235–244

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

This research was supported by Guangxi Natural Science Foundation (2015GXNSFCB1390008) and the Project of High Level Innovation Team and Outstanding Scholar in Guangxi Colleges and Universities (Third batch, 2016).

Availability of data and materials

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article and its additional files.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

JJ planned and designed the research. WJ, QZ, YW, JH, NL, SW, performed experiments. JJ wrote the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Additional files

Additional file 1:

Table S1. The target site sequence of the 20 T0 transgenic plants. (DOCX 20 kb)

Additional file 2:

Table S2. All genes expression profile. (XLSX 3158 kb)

Additional file 3:

Table S3. Differentially expressed genes. (XLSX 111 kb)

Additional file 4:

Table S4. Genes assigned to KEGG. (XLS 50 kb)

Additional file 5:

Table S5. Genes assigned to KEGG pathway. (XLSX 15 kb)

Additional file 6:

Figure S1. Validation of RNA-seq by qPCR. (TIF 685 kb)

Additional file 7:

Figure S2. Heat map of previously known as lemma/palea-related genes. (JPG 866 kb)

Additional file 8:

Table S6. Primers used for constructing the transgenic line. (DOCX 16 kb)

Additional file 9:

Table S7. Primers used for qPCR for this study. (DOCX 18 kb)

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Wang, J., Zhang, Q., Wang, Y. et al. Analysing the rice young panicle transcriptome reveals the gene regulatory network controlled by TRIANGULAR HULL1. Rice 12, 6 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12284-019-0265-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12284-019-0265-2