Abstract

Background

The improvement of rice yield is a crucial global issue, but evaluating yield requires substantial efforts. Rice yield comprises the following indices: panicle number (PN), grain number per panicle (GN), 1000-grain weight, and percentage of ripened grain. To simplify measurements, we analyzed one panicle weight (OPW) as a simplified yield index that integrates GN, grain weight, and percentage of ripened grain, and verified its suitability as a proxy for GN and grain weight in particular.

Results

Quantitative trait locus (QTL) analysis using 190 recombinant inbred lines derived from Koshihikari (large panicle and small grain) and Yamadanishiki (small panicle and large grain), japonica cultivars detected three QTLs on chromosomes 5 (qOPW5), 7 (qOPW7) and 11 (qOPW11). Of these, qOPW5 and qOPW11 were detected over two years. qOPW5 and qOPW7 increased OPW, and qOPW11 decreased it at Yamadanishiki alleles. A chromosome segment substitution line (CSSL) with a genomic segment from Yamadanishiki substituted in the Koshihikari genetic background harboring qOPW5 increased grain weight. qOPW11 had the largest genetic effect of QTLs, which was validated using a CSSL. Substitution mapping using four CSSLs revealed that qOPW11 was located in the range of 1.46 Mb on chromosome 11. The CSSL harboring qOPW11 decreased primary and secondary branch numbers, culm length, and panicle length, and increased PN.

Conclusions

In this study, three QTLs associated with OPW were detected. The CSSL with the novel and largest QTL, qOPW11, differed in some traits associated with both panicle and plant architecture, indicating different functions for the meristem in the vegetative versus the reproductive stages. qOPW5 coincided with an identified QTL for grain width and grain weight, suggesting that qOPW5 was affected by rice grain size. OPW can be considered a useful trait for efficient detection of QTLs associated with rice yield.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Rice is one of the most important crops in the world because it is the staple food for half the global human population, especially in Asia. Rice yield has improved with breeding programs commencing in the 1960s with the utilization of the semi-dwarf1 (Sasaki et al. 2002). Rice grain yield is a complex trait that is associated with many component traits, and the architecture of plant and panicle features such as tiller and panicle branch are important factors. Rice grain yield comprises four indices: panicle number (PN), grain number per panicle (GN), 1000-grain weight, and percentage of ripened grain (Xing and Zhang 2010; Ikeda et al. 2013), where PN is associated with the number of tillers and GN with panicle branching. It is crucial for next generation breeding programs to elucidate the quantitative trait loci (QTLs) and genes that determine plant and panicle architecture. To reduce the effort of separately examining the above four indices, we propose the use of a single combined index value, one panicle weight (OPW). As a simplified foothold-index for rice yield, it is roughly equivalent to the product of GN, grain weight, and the percentage of ripened grain; it also has a direct effect on yield per panicle. Use of this value can potentially contribute to efficient selection for high yield and may prove useful in genetic analyses.

The rice panicle has various characteristics such as primary and secondary branches, rachis, and spikelets (Crowell et al. 2016). Panicle architecture mainly consists of primary and secondary branches, and these traits are strongly related to GN (Ikeda et al. 2013; Peng et al. 2014; Rebolledo et al. 2016). Genes associated with the primary branch number (PBN) and the secondary branch number (SBN) have been cloned from natural and mutant rice variations. Examples of these are Gn1a (Ashikari et al. 2005), DEP1 (Huang et al. 2009), LAX1 (Komatsu et al. 2001), OsSPL14 (Jiao et al. 2010; Miura et al. 2010), SP1 (Li et al. 2009), and APO1 (Ikeda et al. 2007; Ikeda-Kawakatsu et al. 2009). In addition, there exist many fine-mapped QTLs for panicle structure (Xing et al. 2008; Shan et al. 2009; Peng et al. 2014; Zhang et al. 2015; Sasaki et al. 2017). Genome-wide association studies for panicle architecture have recently been performed (Crowell et al. 2016; Rebolledo et al. 2016), and identification of genes associated with diversity of rice panicle has advanced. Of the QTLs and cloned genes associated with panicle architecture, some also affect tiller formation. Mutants of MOC1 and LAX1 reduce the number of both tillers and panicle branches (Komatsu et al. 2001; Li et al. 2003). In contrast, the near isogenic line (NIL) containing the OsSPL14 gene was found to promote panicle branching and decrease tiller numbers (Jiao et al. 2010). Mutants of SP1 and OsARG only affected panicle morphology (Li et al. 2009; Ma et al. 2013). The formation of tillers and panicle branches depends on common, independent, or interactive pathways, and it is likely that the genetic mechanisms controlling these are complex. Elucidation of these pathways is therefore useful for developing an optimized rice plant morphology. As the first step in the screening process, OPW is a useful and efficient measure to examine panicle architecture.

First, we evaluated OPW as a quantitative trait of rice grain yield and performed QTL analysis using recombinant inbred lines (RILs) derived from a cross between Koshihikari (large panicle and small grain) and Yamadanishiki (small panicle and large grain). As the unknown genetic factor for smaller panicle was of particular interest, these two cultivars were considered an appropriate pair for analysis purposes. Next, the major QTL detected on chromosome 11 was validated using chromosome segment substitution lines (CSSLs) to investigate plant and panicle architecture, and grain weight of CSSLs was measured. In the present study, our objectives were (1) to verify the use of OPW in evaluating some indices of rice grain yield – in particular, GN and grain weight; and (2) to elucidate the genetic factors for panicle development in Yamadanishiki.

Results

QTL Analysis

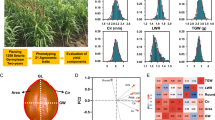

The histograms of the recombinant inbred lines (RILs) for OPW showed a continuous distribution, with transgressive segregations observed in 2014 and 2015 (Fig. 1a, Additional file 1: Figure S1A). Three QTLs were detected on chromosomes 5 (qOPW5), 7 (qOPW7), and 11 (qOPW11; Table 1). The genetic effect of qOPW11 expressed more than 50% of phenotypic variance, and was the largest additive effect among the three QTLs (Table 1). The QTLs, qOPW5 and qOPW11 were detected in both 2014 and 2015. The Yamadanishiki alleles at qOPW5 and qOPW7, and the Koshihikari allele at qOPW11 increased OPW. In addition, no significant correlations between OPW and days to heading (DTH) were observed (Additional file 1: Figure S2), and the QTLs for OPW did not correspond to QTLs for DTH reported previously (Okada et al. 2017; Okada et al. 2018).

Histograms (a and b) and boxplot (c) for one panicle weight (OPW) of the recombinant inbred lines (RILs) from Koshihikari and Yamadanishiki in 2014. The histogram (a) was drawn using all 190 RILs, and the histogram (b) and boxplot (c) used 180 RILs of homozygous genotypes at the nearest single nucleotide polymorphism markers of qOPW5 and qOPW11. The 180 RILs were classified into four classes: class 1: qOPW5_K and qOPW11_Y (45 lines), class 2: qOPW5_Y and qOPW11_Y (44 lines), class 3: qOPW5_K and qOPW11_K (40 lines) and class 4: qOPW5_Y and qOPW11_K (51 lines)

The RILs were divided into four groups by the homozygous genotypes of the nearest markers for qOPW5 and qOPW11 (Fig. 1b and c, Additional file 1: Figure S1B and C). The effect of qOPW5 was clearly visible in the multiple comparison test with qOPW11_K (classes 3 and 4; Fig. 1c), but the epistatic interaction between qOPW5 and qOPW11 was not significant (P = 0.087) in the three-way ANOVA test (Table 2). Class 4 (qOPW5_Y and qOPW11_K) showed the largest OPW of the four groups (Fig. 1b and c). This tendency was consistent over two years (Fig. 1 and Additional file 1: Figure S1).

Validation of qOPW11

CSSL11–4 (the CSSL harboring the qOPW11 region from Yamadanishiki in the Koshihikari genetic background) was selected to validate qOPW11, with the graphical genotypes represented in Fig. 2. The OPW of CSSL11–4 was significantly lower than that of Koshihikari in both 2015 and 2016 (Fig. 3a). The panicle of CSSL11–4 was smaller than that of Koshihikari but similar to that of Yamadanishiki (Fig. 3b, c, and d).

Yield and Plant Traits of CSSLs Harboring qOPW5 or qOPW11

First, we measured 100-grains weight (GWt) of CSSL5–5 (the CSSL harboring the qOPW5 region from Yamadanishiki in the Koshihikari genetic background; Additional file 1: Figure S3), CSSL11–4 and parents. As the result, GWt of CSSL5–5 was heavier than that of Koshihikari over three years (Table 3). GWt of CSSL11–4 in 2015 was larger than that of Koshihikari in 2016 and 2017, and we also detected significant difference in 2016 and 2017; but differences between CSSL11–4 and Koshihikari were smaller (Table 3).

Next, we measured some traits associated with plant and panicle architecture for CSSL11–4. Panicle length (PL), PBN, SBN, and culm length (CL) in CSSL11–4 all were smaller than in Koshihikari, but PN in CSSL11–4 was greater (Fig. 4).

Substitution Mapping of qOPW11

Four CSSLs that had a genomic segment around qOPW11 (Fig. 5) were used for substitution mapping of qOPW11. Of the four lines, the OPWs of three lines (CSSL3–3, 9–2, 11–4) were less than that of Koshihikari in both 2015 and 2016. In contrast, the OPWs of CSSL11–3 were greater than those of these three CSSLs in both years, similar to Koshihikari in 2015, and slightly less than Koshihikari in 2016. As a result, qOPW11 was mapped between aa11004500 and aa11004652, with a physical distance of approximately 1.46 Mb.

Substitution mapping of qOPW11 using the chromosome segment substitution lines (CSSLs) on chromosome 11. Black, white, and gray blocks represent the Yamadanishiki homozygous genotypes, Koshihikari homozygous genotypes, and heterozygous genotypes, respectively. The striped block on CSSL3–3 shows the missing genotype at aa11004506. One panicle weight values are shown for 2015 and 2016. Different letters indicate significant differences between samples in the Tukey-Kramer test

Discussion

Panicle size and architecture are important elements for rice yield. We evaluated one trait related to the panicle, OPW, and examined its suitability for efficient genetics analysis of rice yield. OPW incorporates the following traits: GN, grain size, percentage of ripened grain, and the branching frame of the panicle. The use of OPW facilitated the detection of responsible QTLs using RILs and narrowed down the number of CSSLs, allowing the efficient investigation of panicle and yield components. We detected three QTLs on chromosomes 5, 7, and 11, of which qOPW5 and qOPW11 had consistent effects on OPW (Table 1). No loci associated with panicle traits around qOPW5 and qOPW11 are on record in the Q-TARO (Yonemaru et al. 2010) or Gramene databases (http://www.gramene.org/), suggesting that the two QTLs are novel. Phenotypic variance of OPW in the RILs was mostly explained by qOPW11, and the Yamadanishiki allele at qOPW11 had an effect of decreasing the OPW (Table 1). Therefore, it appears that qOPW11 causes short panicles in Yamadanishiki. qOPW11 was mapped at 1.46 Mb on chromosome 11 by substitution mapping with CSSLs (Fig. 5), and provided a foothold for the map-based cloning.

A QTL for grain width and grain weight was reported by Yoshida et al. (2002), Nagata et al. (2015), and Okada et al. (2017), but they did not identify a QTL associated with panicle traits around qOPW5. A QTL (qGWh5) for grain width was recently identified on chromosome 5 using the same CSSLs used in the present study (Okada et al. 2018). In the present study, it was elucidated that qOPW5 clearly had an effect on grain weight by evaluating GWt over three years (Table 3). GWt of CSSL11–4 in 2015 was larger than GWt in other years (Table 3). Because qGL11 of QTL had the largest effect on grain length in heterozygous region on chromosome 11 in CSSL11–4 in 2015 (Okada et al. 2017; Okada et al. 2018), it appears that qGL11 of CSSL11–4 in 2015 affected GWt. However, CSSL11–4 had slightly heavier GWt than Koshihikari in 2016 and 2017. Therefore, qOPW11 may also have an effect on grain weight, although the possibility exists that two tightly linked QTLs or Yamadanishiki segments in the genetic background influence each other.

The RILs harboring the Yamadanishiki allele at qOPW5 and the Koshihikari allele at qOPW11 showed the highest OPW among the genotype classes (Fig. 1b and c). When qOPW11 contained the Koshihikari allele, the effect of qOPW5 was clearly represented; however, the presence of an epistatic interaction between qOPW5 and qOPW11 was not clear (Fig. 1c, Table 2). It can therefore be concluded that qOPW5 did not affect panicle architecture but did affect grain size and weight, resulting in the increase of panicle weight. The transgressive segregation of the histograms of OPW for the RILs was mostly explained by qOPW5 and qOPW11 (Fig. 1). Further analysis for yield of these QTLs with NILs and pyramiding lines is recommended, since genes associated with grain size also affect panicle traits (Hu et al. 2015; Si et al. 2016).

The phenotype for plant and panicle architecture of CSSL11–4 was clearly different from Koshihikari (Fig. 4). Because there is a positive correlation between PBN and GN (Peng et al. 2014; Rebolledo et al. 2016), we suggest that decrease of OPW in presence of the Yamadanishiki allele was caused by decrease of PBN. Therefore, qOPW11 would affect panicle architecture. Moreover, it is clear that CSSL11–4 expressed a different plant architecture, with traits such as PN and CL derived from Koshihikari (Fig. 4). When the allele of qOPW11 changes from the Yamadanishiki allele to the Koshihikari allele, PL and CL increase and PN decreases (Fig. 4). Yoshida et al. (2002) detected a major QTL for PN on chromosome 11 using double haploid lines derived from a cross between Reiho and Yamadanishiki. The QTL would correspond to qOPW11 because of increasing PN at the Yamadanishiki allele. This suggests that qOPW11 would have different functions for the meristem in the vegetative versus the reproductive stages, when the effect of qOPW11_K would suppress tiller and increase panicle branch. However, fine mapping for qOPW11 should be conducted because it is possible that two tightly linked QTLs affect the measured traits.

Several SPL (SQUAMOSA PROMOTER BINDING PROTEIN-LINE) genes are associated with the formation of both panicle and tiller (Jiao et al. 2010; Miura et al. 2010; Wang et al. 2015; Si et al. 2016), and plant and panicle architecture are changed by the expression level of these genes (Wang et al. 2015; Wang and Zhang 2017). For example, with high expression levels of OsSPL14 at both the vegetative and reproductive stages, tiller number decreased but PBN and SBN increased (Jiao et al. 2010; Miura et al. 2010). In addition, mutants of D14/D88 and D53 associated with strigolactone signaling also showed increased tiller numbers and decreased panicle size (Arite et al. 2009; Gao et al. 2009; Zhou et al. 2013). Therefore, qOPW11 may also be involved with the pathways for both plant and panicle architecture.

Conclusions

We detected three QTLs associated with rice yield using QTL analysis for the single trait OPW. Of the detected QTLs, qOPW5 affected grain size and qOPW11 affected panicle architecture. qOPW11 caused the largest effect, clearly affecting both plant and panicle architecture, and was isolated to 1.46 Mb on chromosome 11. Further analysis of these QTLs will be beneficial in increasing rice yield and elucidating the development of rice plant morphology. OPW can be considered a useful trait for detection of QTLs associated with rice yield.

Methods

Plant Materials and Cultivation Conditions

We used two kinds of plant materials: (1) the recombinant inbred lines (RILs) derived from a cross between the Koshihikari (large panicle and small grain) and Yamadanishiki (small panicle and large grain) japonica cultivars, and (2) the chromosome segment substitution lines (CSSLs) from Yamadanishiki in the Koshihikari genetic background (Okada et al. 2017; Okada et al. 2018). All plants were cultivated in an experimental field located at the Food Resources Education and Research Center of Kobe University (Kasai City, Hyogo Prefecture, Japan) (34.880 N, 134.866E). The RIL population was cultivated in 2014 and 2015. A total of 190 RILs were genotyped with 312 DNA markers. Of these, 310 markers were identified by Okada et al. (2017) and an additional two markers were determined in the present study (C6_3000 and RM6704; Additional file 2: Tables S1 and S2).

The four CSSLs (CSSL3–3, CSSL9–2, CSSL11–3, and CSSL11–4) and the parent plants (Koshihikari and Yamadanishiki) were cultivated in 2015 and 2016 for validation and substitution-mapping of a major QTL for OPW on chromosome 11. Okada et al. (2018) identified genotypes of the four CSSLs.

Phenotypic Evaluation

The OPW trait was measured for QTL analysis, validation, and substitution mapping of a QTL. Eight panicles were harvested per rice plant over 45 days after their flowering date, their weight was measured using an electronic balance to an accuracy of 0.01 g, and the average value of OPW was calculated. In the QTL analysis, this trait was evaluated for three plants per RIL. The data for days to heading (DTH) of RILs and CSSLs are shown in Additional file 1: Figure S2 and Additional file 2: Table S3. The QTLs for DTH of Koshihikari / Yamadanishiki crossed populations were previously identified for qDTH3 on chromosome 3 and qDTH6 on chromosome 6 (Okada et al. 2017; Okada et al. 2018). qDTH3 at the Yamadanishiki allele had a very large genetic effect which increased at about 20 days, and expressed phenotypic variance of DTH in the RIL population beyond 75%. Histograms of RILs therefore show two peaks. The DTHs of used CSSLs showed a similar to that of Koshihikari because these lines had qDTH3 homozygous at the Koshihikari allele.

Several traits were measured to evaluate the effect of qOPW5 and qOPW11. First, GWt was measured in CSSL5–5, CSSL11–4 and parents in 2015, 2016 and 2017. The 2015 and 2016 values are published in Okada et al. (2018). CL, PL, PN, PBN, and SBN were measured on CSSL11–4 as well as the parent plants in order to examine the QTL effect on other agronomic traits of plant and panicle architecture.

QTL Analysis and Statistical Analysis

QTL analysis was performed on 190 RILs using Windows QTL Cartographer 2.5 (Wang et al. 2012). QTLs were detected using the composite interval mapping method (Zeng 1994) with window size and walk speed set at 5 and 1 cM, respectively. The empirical threshold (α = 0.05) for logarithm of odds (LOD) values was determined from 1000 permutations (Churchill and Doerge 1994). Confidence intervals were calculated from a 1-LOD support interval.

For two of the detected QTLs (qOPW5 and qOPW11), the 190 RILs were classified by the genotypes of the nearest markers (ac05000341 and aa11004535) on chromosomes 5 and 11 (Additional file 2: Table S1). The 180 homozygous lines were classified into four classes: class 1 – Koshihikari homozygous allele at qOPW5 (qOPW5_K) and Yamadanishiki homozygous allele at qOPW11 (qOPW11_Y) (45 lines); class 2 – Yamadanishiki homozygous allele at qOPW5 (qOPW5_Y) and qOPW11_Y (44 lines); class 3 – qOPW5_K and Koshihikari homozygous allele at qOPW11 (qOPW11_K) (40 lines); and class 4 – qOPW5_Y and qOPW11_K (51 lines). The 10 heterozygous RILs were excluded. Three-way ANOVA and multiple Tukey-Kramer comparisons were conducted with statistics software R 3.4.1 (R Core Team 2017) and histograms and boxplots were created using the R package ‘ggplot2’.

Comparison between the CSSLs harboring qOPW5 or qOPW11 and Koshihikari was performed by Dunnett’s test. Validation of qOPW11 and evaluation of effects on other traits was carried out using a two-sided t-test for OPW, CL, PL, PN, PBN, and SBN between Koshihikari and CSSL11–4. Substitution mapping in the 2015 and 2016 results was statistically analyzed using one-way ANOVA.

Abbreviations

- ANOVA:

-

Analysis of variance

- APO1 :

-

ABERRANT PANICLE ORGANIZATION 1

- CL:

-

Culm length

- CSSL:

-

Chromosome segment substitution line

- D14/D88 :

-

DWARF 14/DWARF88

- D53 :

-

DWARF 53

- DEP1 :

-

DENSE AND ERECT PANICLE 1

- DTH:

-

Days to heading

- GN:

-

Grain number per panicle

- Gn1a :

-

GRAIN NUMBER 1a

- GWt:

-

100-grain weight

- LAX1 :

-

LAX PANICLE 1

- LOD:

-

Logarithm of odds

- MOC1 :

-

MONOCULM 1

- NIL:

-

Near isogenic line

- OPW:

-

One panicle weight

- OsARG :

-

ARGINASE

- OsSPL14 :

-

SOUAMOSA PROMOTER BINDING PROTEIN-LIKE 14

- PBN:

-

Primary branch number

- PL:

-

Panicle length

- PN:

-

Panicle number

- QTL:

-

Quantitative trait locus

- RIL:

-

Recombinant inbred line

- SBN:

-

Secondary branch number

- SNP:

-

Single nucleotide polymorphism

- SP1 :

-

SHORT PANICLE 1

- SPL :

-

SQUAMOSA PROMOTER BINDING PROTEIN-LIKE

References

Arite T, Umehara M, Ishikawa S, Hanada A, Maekawa M, Yamaguchi S, Kyozuka J (2009) d14, a strigolactone-insensitive mutant of rice, shows an accelerated outgrowth of tillers. Plant Cell Physiol 50(8):1416–1424

Ashikari M, Sakakibara H, Lin S, Yamamoto T, Takashi T, Nishimura A, Angeles ER, Qian Q, Kitano H, Matsuoka M (2005) Cytokinin oxidase regulates rice grain production. Science 309:741–745

Churchill GA, Doerge RW (1994) Empirical threshold values for quantitative trait mapping. Genetics 138:963–971

Core Team R (2017) R: a language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for statistical computing, Vienna URL http://www.R-project.org/

Crowell S, Korniliev P, Falcão A, Ismail A, Gregorio G, Mezey J, McCouch S (2016) Genome-wide association and high-resolution phenotyping link Oryza sativa panicle traits to numerous trait-specific QTL clusters. Nat Commun 7:10527

Gao Z, Qian Q, Liu X, Yan M, Feng Q, Dong G, Liu J, Han B (2009) Dwarf 88, a novel putative esterase gene affecting architecture of rice plant. Plant Mol Biol 71:265–276

Hu J, Wang Y, Fang Y, Zeng L, Xu J, Yu H, Shi Z, Pan J, Zhang D, Kang S, Zhu L, Dong G, Guo L, Zeng D, Zhang G, Xie L, Xiong G, Li J, Qian Q (2015) A rare allele of GS2 enhances grain size and grain yield in rice. Mol Plant 8:1455–1465

Huang X, Qian Q, Liu Z, Sun H, He S, Luo D, Xia G, Chu C, Li J, Fu X (2009) Natural variation at the DEP1 locus enhances grain yield in rice. Nat Genet 41(4):494–497

Ikeda K, Ito M, Nagasawa N, Kyozuka J, Nagato Y (2007) Rice ABERRANT PANICLE ORGANIZATION 1, encoding an F-box protein, regulates meristem fate. Plant J 51:1030–1040

Ikeda M, Miura K, Aya K, Kitano H, Matsuoka M (2013) Genes offering the potential for designing yield-related traits in rice. Curr Opin Plant Bio 16:213–220

Ikeda-Kawakatsu K, Yasuno N, Oikawa T, Iida S, Nagato Y, Maekawa M, Kyozuka J (2009) Expression level of ABERRANT PANICLE ORGANIZATION1 determines rice inflorescence form through control of cell proliferation in the meristem. Plant Physiol 150:736–747

Jiao Y, Wang Y, Xue D, Wang J, Yan M, Liu G, Dong G, Zeng D, Lu Z, Zhu X, Qian Q, Li J (2010) Regulation of OsSPL14 by OsmiR156 defines ideal plant architecture in rice. Nat Genet 42(6):541–544

Komatsu M, Maekawa M, Shimamoto K, Kyozuka J (2001) The LAX1 and FRIZZY PANICLE 2 genes determine the inflorescence architecture of rice by controlling rachis-branch and spikelet development. Dev Biol 23:364–373

Li S, Qian Q, Fu Z, Zeng D, Meng X, Kyozuka J, Maekawa M, Zhu X, Zhang J, Li J, Wang Y (2009) Short panicle1 encodes a putative PTR family transporter and determines rice panicle size. Plant J 58:592–605

Li X, Qian Q, Fu Z, Wang Y, Xiong G, Zeng D, Wang X, Liu X, Teng S, Hiroshi F, Yuan M, Luo D, Han B, Li J (2003) Control of tillering in rice. Nature 422:618–621

Ma X, Cheng Z, Qin R, Qiu Y, Heng Y, Yang H, Ren Y, Wang X, Bi J, Ma X, Zhang X, Wang J, Lei C, Guo X, Wang J, Wu F, Jiang L, Wang H, Wan J (2013) OsARG encodes an arginase that plays critical roles in panicle development and grain production in rice. Plant J 73:190–200

Miura K, Ikeda M, Matsubara A, Song XJ, Ito M, Asano K, Matsuoka M, Kitano H, Ashikari M (2010) OsSPL14 promotes panicle branching and higher grain productivity in rice. Nat Genet 42(6):545–549

Nagata K, Ando T, Nonoue Y, Mizubayashi T, Kitazawa N, Shomura A, Matsubara K, Ono N, Mizobuchi R, Shibaya T, Ogiso-Tanaka E, Hori K, Yano M, Fukuoka S (2015) Advanced backcross QTL analysis reveals complicated genetic control of rice grain shape in a japonica × indica cross. Breed Sci 65:308–318

Okada S, Onogi A, Iijima K, Hori K, Iwata H, Yokoyama W, Suehiro M, Yamasaki M (2018) Identification of QTLs for rice grain size using a novel set of chromosome segment substitution lines derived from Yamadanishiki against a Koshihikari genetic background. Breed Sci 68(2):210–218

Okada S, Suehiro M, Ebana K, Hori K, Onogi A, Iwata H, Yamasaki M (2017) Genetic dissection of grain traits in Yamadanishiki, an excellent sake-brewing rice cultivar. Theor Appl Genet 130:2567–2585

Peng Y, Gao Z, Zhang B, Liu C, Xu J, Ruan B, Hu J, Dong G, Guo L, Liang G, Qian Q (2014) Fine mapping and candidate gene analysis of a major QTL for panicle structure in rice. Plant Cell Rep 33:1843–1850

Rebolledo MC, Pena AL, Duitama J, Cruz DF, Dingkuhn M, Grenier C, Tohme J (2016) Combining image analysis, genome wide association studies and different field traits to reveal stable genetic regions related to panicle architecture and the number of spikelets per panicle in rice. Front Plant Sci 7:1384

Sasaki A, Ashikari M, Ueguchi-Tanaka M, Itoh H, Nishimura A, Swapan D, Ishiyama K, Saito T, Kobayashi M, Khush GS, Kitano H, Matsuoka M (2002) A mutant gibberellin-synthesis gene in rice. Nature 416:701–702

Sasaki K, Fujita D, Koide Y, Lumanglas PD, Gannaban RB, Tagle AG, Obara M, Fukuta Y, Kobayashi N, Ishimaru T (2017) Fine mapping of a quantitative trait locus for spikelet number per panicle in a new plant type rice and evaluation of a near isogenic line for grain productivity. J Exp Bot 68(11):2693–2702

Shan JX, Zhu MZ, Shi M, Gao JP, Lin HX (2009) Fine mapping and candidate gene analysis of spd6, responsible for small panicle and dwarfness in wild rice (Oryza rufipogon Griff.). Theor Appl Genet 119:827–836

Si L, Chen J, Huang X, Gong H, Luo J, Hou Q, Zhou T, Lu T, Zhu J, Shangguan Y, Chen E, Gong C, Zhao Q, Jing Y, Zhao Y, Li Y, Cui L, Fan D, Lu Y, Weng Q, Wang Y, Zhan Q, Liu K, Wei X, An K, An G, Han B (2016) OsSPL13 controls grain size in cultivated rice. Nat Genet 48(4):447–456

Wang L, Sun S, Jin J, Fu D, Yang X, Weng X, Xu C, Li X, Xiao J, Zhang Q (2015) Coordinated regulation of vegetative and reproductive branching in rice. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 112(50):15504–15509

Wang L, Zhang Q (2017) Boosting rice yield by fine-tuning SPL gene expression. Trends Plant Sci 22(8):643–646

Wang S, Basten CJ, Zeng ZB (2012) Windows QTL Cartographer 2.5. Department of Statistics. North Carolina State University, Raleigh

Xing Y, Zhang Q (2010) Genetic and molecular bases of rice yield. Annu Rev Plant Biol 61:421–442

Xing YZ, Tang WJ, Xue WY, Xu CG, Zhang Q (2008) Fine mapping of a major quantitative trait loci, qSSP7, controlling the number of spikelets per panicle as a single Mendelian factor in rice. Theor Appl Genet 116:789–796

Yonemaru J-I, Yamamoto T, Fukuoka S, Uga Y, Hori K, Yano M (2010) Q-TARO: QTL annotation Rice online database. Rice 3:194–203

Yoshida S, Ikegami M, Kuze J, Sawada K, Hashimoto Z, Ishii T, Nakamura C, Kamijima O (2002) QTL analysis for plant and grain characters of sake-brewing rice using doubled haploid population. Breed Sci 52:309–317

Zeng ZB (1994) Precision mapping of quantitative trait loci. Genetics 136:1457–1468

Zhang L, Wang J, Wang J, Wang L, Ma B, Zeng L, Qi Y, Li Q, He Z (2015) Quantitative trait locus analysis and fine mapping of the qPL6 locus for panicle length in rice. Theor Appl Genet 128:1151–1161

Zhou F, Lin Q, Zhu L, Ren Y, Zhou K, Shabek N, Wu F, Mao H, Dong W, Gan L, Ma W, Gao H, Chen J, Yang C, Wang D, Tan J, Zhang X, Guo X, Wang J, Jiang L, Liu X, Chen W, Chu J, Yan C, Ueno K, Ito S, Asami T, Cheng Z, Wang J, Lei C, Zhai H, Wu C, Wang H, Zheng N, Wan J (2013) D14–SCFD3-dependent degradation of D53 regulates strigolactone signalling. Nature 504:406–410

Acknowledgements

We thank Miki Suehiro and Wakana Yokoyama for acting as technical support staff during the experiments.

Funding

This work was supported by the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (JSPS) Grants-in-Aid for Scientific Research (KAKENHI) for JSPS Fellows 17 J01082 and the Japan Science and Technology Agency (JST) CREST Grant Number JPMJCR17O3.

Availability of Data and Materials

Additional file 2 Table S1 includes all the genotypes of the RILs supporting the conclusions of this research. Okada et al. (2018) documents the genotypes of the CSSLs.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

SO, MS, and MY designed the experiments. SO, and MS phenotyped the materials. SO and MS performed the statistical analysis. SO and MY wrote the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics Approval and Consent to Participate

Not applicable.

Consent for Publication

Not applicable.

Competing Interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Additional files

Additional file 1:

Figure S1. The histograms (A and B) and boxplot (C) for OPW of RILs from Koshihikari/Yamadanishiki in 2015. The histogram (B) and boxplot used 180 RILs homozygous at the nearest SNP markers of qOPW5 and qOPW11. The 180 RILs were classified into four class; class1: qOPW5_K and qOPW11_Y (45 lines), class2: qOPW5_Y and qOPW11_Y (44 lines), class3: qOPW5_K and qOPW11_K (40 lines) and class 4: qOPW5_Y and qOPW11_K (51 lines). Figure S2. Scatter plots between OPW and days to heading for RILs in 2014 (A) and 2015 (A). No significant correlations were observed with Kendall’s rank correlation both years (2014; tau = 0.065, P = 0.19 and 2015; tau = − 0.076, P = 0.13). Figure S3. Graphical genotype of CSSL5–5. (PPTX 416 kb)

Additional file 2:

Table S1. Genotypes of RILs. Table S2. Additional markers using genotypes of RILs. Table S3 Days to heading of CSSLs and parents. (XLSX 212 kb)

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Okada, S., Sasaki, M. & Yamasaki, M. A novel Rice QTL qOPW11 Associated with Panicle Weight Affects Panicle and Plant Architecture. Rice 11, 53 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12284-018-0246-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12284-018-0246-x