Abstract

Background

Previous studies have shown that migraine and sleep disturbances are closely associated. Excessive daytime sleepiness (EDS) is a common symptom of various types of sleep disturbance. Findings from clinic-based studies suggest that a high percentage of migraineurs experience EDS. However, the prevalence and clinical impact of EDS among migraineurs at the population level have rarely been reported. The objective of this study was to investigate the prevalence and impact of EDS among migraineurs using a population-based sample in Korea.

Methods

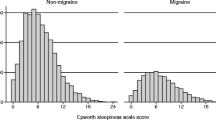

We selected a stratified random sample of Koreans aged 19 to 69 years and evaluated them using a semi-structured interview designed to identify EDS, headache type, and the clinical characteristics of migraine. If the score on the Epworth Sleepiness Scale (ESS) was more than or equal to 11, the participant was classified as having EDS.

Results

Of the 2,695 participants that completed the interview, 143 (5.3 %) and 313 (11.6 %) were classified as having migraine and EDS, respectively. The prevalence of EDS was significantly higher in participants with migraine (19.6 %) and non-migraine headache (13.4 %) compared to non-headache controls (9.4 %). Migraineurs with EDS had higher scores on the Visual Analogue Scale (VAS) for headache intensity (6.9 ± 1.8 vs. 6.0 ± 1.9, p = 0.014) and Headache Impact Test-6 (59.8 ± 10.2 vs. 52.5 ± 8.2, p < 0.001) compared to migraineurs without EDS.

Conclusions

Approximately 20 % of migraineurs had EDS in this population-based sample. Excessive daytime sleepiness was associated with an exacerbation of some migraine symptoms.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Migraine and sleep disturbances are common neurological problems in the general population [1–3]. The close association between the two conditions has been reported in numerous clinic- and population-based studies. Both excessive sleep and sleep deprivation are common triggering factors of migraine and sleep may terminate an attack of migraine [4, 5]. Insomnia is a common comorbidity of migraine in cross-sectional and longitudinal studies [6, 7]. Habitual snoring and sleep bruxism are associated with an exacerbation of migraine [8, 9]. Morning headache in obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) patients may exhibit migraine-like headache [10]. Restless legs syndrome has been reported to be associated with migraine in case-controlled and population-based studies [11, 12].

Excessive daytime sleepiness (EDS) is defined as ‘sleepiness in a situation when an individual would be expected to be awake and alert’ [13]. EDS is not a disorder in and of itself, but represents symptoms of several broad conditions including poor sleep quality, depression, anxiety, sleep-disordered breathing, and obesity metabolic syndrome [14]. Besides impairing quality of life, EDS may lead to potentially problematic conditions such as attention deficits and sleep attacks [15]. The prevalence of EDS has ranged between 10 % and 20 % in the general population [16, 17].

For psychiatric conditions, anxiety and depression has been reported to be associated with EDS. Individuals with depression have frequently EDS (57.1 %) and a quarter of individuals with EDS have moderate-to-severe depression in survey using Beck Depression Inventory [18, 19]. Anxiety was associated with an increased occurrence of EDS in a 20-year prospective community-based study from Switzerland [17].

The association between EDS and several common neurological diseases such as Parkinson’s disease, epilepsy, and migraine has been previously reported. A case-controlled study from Italy noted that subjects with episodic migraine (EM) showed an increased odds ratio [14 % vs. 5 %; odds ratio (OR) = 3.1; 95 % confidence interval (CI) 1.1–8.9] for EDS compared to age- and sex-matched healthy controls [15]. Another case-controlled study showed a positive association between EDS and chronic migraine (CM) [20]. A case-series study in the United States showed that a significant proportion of participants with migraine also had EDS [21]. A community-based study in Norway showed increased ORs (OR = 3.3, 95 % CI 1.0–10.2) for EDS among migraineurs compared to headache-free individuals [22]. However, previous reports regarding the association between EDS and migraine were predominantly clinic-based studies and the association between them has seldom been examined in the general population. In addition, the clinical characteristics of migraine associated with EDS have not yet been reported.

The Korean Headache-Sleep Study (KHSS) is a nation-wide population-based interview survey regarding headache and sleep disturbance [12]. It provides an opportunity to assess comorbidity between EDS and migraine as well as elucidate the clinical characteristics of migraine relative to the presence of comorbid EDS. The present study investigated 1) the prevalence of migraine and/or EDS in a general population-based sample; 2) the comorbidity between migraine and EDS in association with potential covariates such as anxiety, depression and poor sleep quality; and 3) the clinical characteristics of migraine comorbid with EDS using the data available from the KHSS.

Methods

Study population and survey process

The study was a nationwide, cross-sectional survey of headache and sleep in the Korean population in adults aged 19–69 years. The study design and methods have been previously described in detail [12]. Briefly, we adopted a two-stage systematic random sampling method in all Korean territories except Jeju-do, proportional to the distribution of the population, which resulted in a sample of 2,695 individuals. Subjects were stratified according to age, gender, size of residential area and educational level. To minimize bias, we informed participants that the topic of the survey was social health issues rather than headache. Trained interviewers conducted structured interviews using a questionnaire to diagnose headache type, sleep duration, sleepiness, anxiety, and depression door-to-door using a face-to-face interview. The interview included questions on headache symptoms and sleep status. All interviewers were employed by Gallup Korea and had previous social survey interviewing experience. The study was conducted from November 2011 to January 2012. It was approved by the institutional review board/ethics committee of Hallym University Sacred Heart Hospital and was performed in accordance with the ethical standards described in the 1964 Declaration of Helsinki and its subsequent amendments [23]. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants.

Migraine assessment

We diagnosed migraine using a questionnaire. The questionnaire established a headache profile which was designed to align with the second edition of the International Classification of Headache Disorders (ICHD-2) [24]. We investigated the severity of headache based on its effects on daily activity (mild, moderate, or severe) and using a visual analogue scale (VAS). Furthermore, we surveyed the headache frequency as following question. “How many days do you experience the headache every month?” Migraine was diagnosed based on the ICHD-2 criteria for migraine without aura (code 1.1) [24]. We did not attempt to separately diagnose migraine with and without aura. As such, both were included in the present study. The questions used to diagnose migraine have 75.0 % sensitivity and 88.2 % specificity, verified by comparing the diagnoses from the survey with those of doctors obtained from an additional telephone interview. This validation process has been previously described in detail [25].

Non-migraine headache assessment

If a participant responded positively to the question ‘In the past year, have you had at least 1 headache lasting more than 1 min?’ and was not diagnosed as having migraine, she or he was diagnosed as having non-migraine headaches.

Excessive daytime sleepiness, sleep duration and poor sleep quality assessment

We used the Epworth Sleepiness Scale (ESS) for assessing participants’ daytime sleepiness. The total ESS score ranged from 0 to 24. If a participant scored more than or equal to 11 on the ESS, they were classified as having EDS. The ESS has been previously validated in the Korean language [26]. The Korean version of the ESS has been reported to have good internal consistency (Cronbach’s α = 0.90) and test-retest reliability (r = 0.78 to 0.93)

We assessed the weekday and weekend sleep durations of participants. Average sleep duration was defined as [(weekday sleep duration × 5) + (weekend sleep duration × 2)]/7. Short sleep duration was defined as average sleep duration of less than 6 h and poor sleep quality was defined as a Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index score (PSQI) of more than 5.

Anxiety and depression assessment

We used the Goldberg Anxiety Scale (GAS) for measuring self-reported anxiety symptomology. If a participant provides a positive response for two or more of the first four screening questions and five or more of all GAS questions, they were characterized as having anxiety [27]. The Korean version of the GAS has been reported to have 82.0 % sensitivity and 94.4 % specificity [28].

The Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9) was used for diagnosing depression [29]. If a participant’s PHQ-9 score was 10 or more, they were categorized as having depression. The Korean PHQ-9 has been found to have 81.1 % sensitivity and 89.9 % specificity [30].

Statistical analysis

We compared EDS prevalence among non-headache controls, and participants with non-migraine headache and migraine, using the chi-square test. We conducted a multivariable logistic regression analysis, adjusting for anxiety, depression, short sleep duration (average sleep duration less than 6 h), and poor sleep quality (a PSQI score of more than 5). We used logistic regression to evaluate the association between migraine and EDS according to headache frequency and calculated odds ratios (ORs) and their 95 % confidence intervals (CIs). We compared the clinical characteristics of participants with migraine with and without EDS using Student’s t-test for continuous variables and the chi-square test for categorical variables. p-values of <0.05 were considered statistically significant. The results were analysed using the statistical software SPSS 22.0 (IBM, Armonk, NY, USA).

As with most survey studies, missing data from a lack of responding occurred on several items. The data reported are the available data and therefore some variables deviate from the overall sample size of n = 2,695. Imputation techniques were not employed to minimize non-response effects [31].

Results

Survey

Our interviewers approached 7,430 individuals and 3,114 of them agreed to take the survey. Of them, 2,695 subjects completed the survey (Fig. 1). The distribution of age, gender, size of residential area, and educational level were not significantly different from those of the Korean general population (Table 1).

Prevalence of migraine and non-migraine headache

Of the 2,695 respondents, 143 (5.3 %) met the ICHD-2 criteria for migraine and 1,130 (41.9 %) were classified as having non-migraine headache. Finally, 1,422 participants (52.8 %) were classified as non-headache controls.

Excessive daytime sleepiness and migraine

Three hundred and thirteen (11.6 %) subjects reported ESS scores in an excess of 11 and were therefore classified as having EDS (Table 1). Among the 143 participants with migraine, 28 (19.6 %) were classified as also having EDS. Of the 1,130 participants with non-migraine headache and the 1,422 classified as non-headache controls, 151 (13.4 %) and 134 (9.4 %) were classified as having EDS, respectively. The prevalence of EDS was significantly higher among participants with migraine (OR = 2.3, 95 % CI = 1.5–3.7, p < 0.000) and non-migraine headache (OR = 1.5, 95 % CI = 1.2–1.9, p = 0.002) compared to non-headache controls. However, the prevalence of EDS was not significantly different between participants with migraine and those with non-migraine headache (OR = 1.6, 95 % CI = 1.0–2.5, p = 0.055) (Fig. 2).

Univariable logistic regression revealed that EDS prevalence among participants with migraine (OR = 2.3, 95 % CI = 1.5–3.7, p < 0.001) and non-migraine headache (OR = 1.5, 95 % CI = 1.2–1.9, p = 0.002) had increased ORs for EDS compared to non-headache controls. Anxiety (OR = 2.4, 95 % CI = 1.7–3.2, p < 0.001), depression (OR = 6.2, 95 % CI = 4.2–9.1, p < 0.001), short sleep duration (OR = 1.4, 95 % CI = 0.9–1.9, p = 0.122), and poor sleep quality (OR = 3.3, 95 % CI = 2.6–4.3) also had increased ORs for EDS. In the multivariable logistic regression for EDS adjusting for anxiety and depression (Model 1), migraine was not associated with increased ORs for EDS. After adjusting for short sleep duration (<6 h) and poor sleep quality (PSQI score > 5) (Model 2), however, non-migraine headache and migraine were revealed to have statistically significant ORs for EDS. The final model adjusting for anxiety, depression, short sleep duration, and poor sleep quality (Model 3), indicated that those with non-migraine headache and migraine did not have statistically significant ORs for EDS relative to non-headache controls (Table 2).

Excessive daytime sleepiness according to the headache frequency of migraine

Although not statistically significant, there was a tendency towards increased prevalence of EDS in migraineurs with at least 10 attacks per month (OR = 1.5, 95 % CI = 0.4–5.8, p = 0.557) compared to those with less than one attack a month. The ESS scores were not significantly different among migraineurs with less than one attack per month (6.2 ± 3.8), 1–9 attacks per month (7.4 ± 4.6), or at least 10 attacks per month (7.2 ± 4.9, p = 0.330).

Clinical characteristics of subjects having migraine with and without EDS

We investigated the headache characteristics, headache frequency, VAS score for pain intensity, HIT-6 scores, psychiatric comorbidities such as anxiety and depression of participants with migraine grouped according the presence of EDS. Unilateral pain (39.3 % vs. 60.9 %, p = 0.039) was less prevalent and moderate-to-severe pain intensity (96.4 % vs. 76.5 %, p = 0.017) was more prevalent among migraineurs with EDS compared to migraineurs without EDS. Additionally, VAS scores for pain intensity (6.9 ± 1.8 vs. 6.0 ± 1.9, p = 0.014), HIT-6 scores (59.8 ± 10.2 vs. 52.5 ± 8.2, p < 0.001) and the prevalence of depression (42.9 % vs. 10.4 %, p < 0.001) was higher in migraineurs with EDS than those without EDS. The other measures did not significantly differ with the presence of EDS (Table 3).

Discussion

The key findings in the present study were: (1) the prevalence of migraine and EDS in the Korean general population were 5.3 % and 11.6 %, respectively; (2) the prevalence of EDS was significantly higher among participants with migraine (19.6 %) and non-migraine headache (13.4 %) compared to non-headache controls (9.4 %); and (3) some clinical characteristics of migraine were more profound among migraineurs with EDS compared to migraineurs without EDS.

The 1-year prevalence of migraine in the present study was 5.3 % (2.7 % for men and 7.9 % for women). The 1-year prevalence of migraine in Asian countries has been found to range between 4.7 % and 9.1 % in most previous studies [32]. Our findings are similar to those reported in previous studies from Asian countries. The prevalence of migraine in Asia is relatively lower than that of western countries.

We found that the prevalence of EDS was 11.6 % in the Korean general population. Previous population-based studies have reported EDS using ESS mostly ranging from 10 % to 20 %. Three Australian studies among adults reported that EDS prevalence ranged from 11.7 % to 15.3 % [33–35]. A study in Singapore revealed an EDS prevalence of 9.0 % [36]. A previous study using data from the Korean Genome Epidemiology Study found that the prevalence of EDS was 12.2 % [37]. Our study showed a similar EDS prevalence to that from previous studies and therefore verified the reliability of the sampling and EDS diagnosis in our study.

Excessive daytime sleepiness has been reported to be associated with poor sleep quality and psychiatric conditions [38, 39]. Poor sleep quality is reported to be associated psychiatric conditions [40–42]. Furthermore, migraineurs were reported to have poor sleep quality and higher psychiatric comorbid conditions compared to non-headache controls [43–45]. In the present study, participants with migraine had an increased OR for EDS compared to non-headache controls in the univariable regression analysis. After adjusting for anxiety, depression, short sleep duration, and poor sleep quality, migraine was no longer a significant predictor of EDS while poor sleep quality and depression maintained significant associations with EDS (Table 3). Previous case-controlled studies have demonstrated similar findings. EM and CM had increased ORs for EDS in a univariate analysis [15, 20]. However, after adjusting for poor sleep quality, drugs, and gender, EM and CM were no longer statistically significant. These findings suggest that a significant association between migraine and EDS in a univariable analysis may be attributable to poor sleep quality and/or depression among migraineurs rather than the migraine itself.

In the present study, migraineurs with EDS experienced more severe headache intensity, reported a higher impact of the headache, and more depressive symptomology than those without EDS. These findings suggest that migraineurs with EDS have more severe clinical burden than migraineurs without EDS. Considering findings in the present study, physicians should carefully investigate the level of EDS and factors that exacerbate it, such as poor sleep quality and depressive symptomology when caring for patients with migraine.

This study had some limitations. First, although our research is a large population-based study with low sampling error, its statistical power for executing a subgroup analysis was limited. Some results might not have reached statistical significance because of the limited sample size. Second, this study is cross-sectional and the directionality of the association is uncertain. It cannot be determined whether migraine causes EDS or vice versa. Third, we surveyed the sleep habits of participants based solely on self-report. Further, we did not use any tool to evaluate characteristics of sleep such as polysomnography, which could further explore the sleep architecture, total sleep time, sleep efficiency, or other relevant sleep variables among participants with EDS.

Our study has several strengths. First, this study has a large sample size in a population-based setting and the estimated sampling error was low. Second, we investigated risk factors for EDS after adjusting for sleep duration. Third, we assessed the clinical features of migraine in participants with EDS compared with those without EDS.

Conclusions

In summary, migraineurs had a higher prevalence of EDS relative to non-headache controls. Further, migraineurs with EDS experienced a more severe headache, depressive mood, and higher impact of headache. The presence of EDS should be carefully evaluated in migraineurs, in order to relieve the headache as well as reduce the impact of headache.

Abbreviations

EDS, excessive daytime sleepiness; ESS, epworth Sleepiness Scale; VAS visual Analogue Scale; OSA, obstructive sleep apnea; EM, episodic migraine; CI, confidence interval; CM, chronic migraine; ICHD, International Classification of Headache Disorders; KHSS, Korean Headache-Sleep Study; PSQI, Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index score; GAS, Goldberg Anxiety Scale; PHQ-9 Patient Health Questionnaire-9; HIT-6 Headache Impact Test-6; OR odds ratio

References

Rains JC, Poceta JS, Penzien DB (2008) Sleep and headaches. Curr Neurol Neurosci Rep 8(2):167–175

Aguggia M, Cavallini M, Divito N, Ferrero M, Lentini A, Montano V et al (2011) Sleep and primary headaches. Neurol Sci 32(Suppl 1):S51–54

Freedom T, Evans RW (2013) Headache and sleep. Headache 53(8):1358–1366

Kelman L, Rains JC (2005) Headache and sleep: examination of sleep patterns and complaints in a large clinical sample of migraineurs. Headache 45(7):904–910

Inamorato E, Minatti-Hannuch SN, Zukerman E (1993) The role of sleep in migraine attacks. Arq Neuropsiquiatr 51(4):429–432

Sancisi E, Cevoli S, Vignatelli L, Nicodemo M, Pierangeli G, Zanigni S et al (2010) Increased prevalence of sleep disorders in chronic headache: a case–control study. Headache 50(9):1464–1472

Odegard SS, Sand T, Engstrom M, Stovner LJ, Zwart JA, Hagen K (2011) The long-term effect of insomnia on primary headaches: a prospective population-based cohort study (HUNT-2 and HUNT-3). Headache 51(4):570–580

Scher AI, Lipton RB, Stewart WF (2003) Habitual snoring as a risk factor for chronic daily headache. Neurology 60(8):1366–1368

Fernandes G, Franco AL, Goncalves DA, Speciali JG, Bigal ME, Camparis CM (2013) Temporomandibular disorders, sleep bruxism, and primary headaches are mutually associated. J Orofac Pain 27(1):14–20

Suzuki K, Miyamoto M, Miyamoto T, Numao A, Suzuki S, Sakuta H et al (2015) Sleep apnoea headache in obstructive sleep apnoea syndrome patients presenting with morning headache: comparison of the ICHD-2 and ICHD-3 beta criteria. J Headache Pain 16:56

Schurks M, Winter AC, Berger K, Buring JE, Kurth T (2012) Migraine and restless legs syndrome in women. Cephalalgia 32(5):382–389. doi:10.1177/0333102412439355

Cho SJ, Chung YK, Kim JM, Chu MK (2015) Migraine and restless legs syndrome are associated in adults under age fifty but not in adults over fifty: a population-based study. J Headache Pain 16:554

Arand D, Bonnet M, Hurwitz T, Mitler M, Rosa R, Sangal RB (2005) The clinical use of the MSLT and MWT. Sleep 28(1):123–144

Bixler EO, Vgontzas AN, Lin HM, Calhoun SL, Vela-Bueno A, Kales A (2005) Excessive daytime sleepiness in a general population sample: the role of sleep apnea, age, obesity, diabetes, and depression. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 90(8):4510–4515

Barbanti P, Fabbrini G, Aurilia C, Vanacore N, Cruccu G (2007) A case–control study on excessive daytime sleepiness in episodic migraine. Cephalalgia 27(10):1115–1119

Carskadon MA (1993) Evaluation of excessive daytime sleepiness. Neurophysiol Clin 23(1):91–100

Hasler G, Buysse DJ, Gamma A, Ajdacic V, Eich D, Rossler W et al (2005) Excessive daytime sleepiness in young adults: a 20-year prospective community study. J Clin Psychiatry 66(4):521–529

Chellappa SL, Araujo JF (2006) Excessive daytime sleepiness in patients with depressive disorder. Rev Bras Psiquiatr 28(2):126–129

Hublin C, Kaprio J, Partinen M, Heikkila K, Koskenvuo M (1996) Daytime sleepiness in an adult, Finnish population. J Intern Med 239(5):417–423

Barbanti P, Aurilia C, Egeo G, Fofi L, Vanacore N (2013) A case–control study on excessive daytime sleepiness in chronic migraine. Sleep Med 14(3):278–281

Peres MF, Stiles MA, Siow HC, Silberstein SD (2005) Excessive daytime sleepiness in migraine patients. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 76(10):1467–1468

Odegard SS, Engstrom M, Sand T, Stovner LJ, Zwart JA, Hagen K (2010) Associations between sleep disturbance and primary headaches: the third Nord-Trondelag Health Study. J Headache Pain 11(3):197–206

World Medical A (2001) Ethical principles for medical research involving human subjects. Eur J Emerg Med 8(3):221–223

Headache Classification Subcommittee of the International Headache S (2004) The international classification of headache disorders: 2nd edition. Cephalalgia 24(Suppl 1):9–160

Kim BK, Chu MK, Lee TG, Kim JM, Chung CS, Lee KS (2012) Prevalence and impact of migraine and tension-type headache in Korea. J Clin Neurol 8(3):204–211

Cho YW, Lee JH, Son HK, Lee SH, Shin C, Johns MW (2011) The reliability and validity of the Korean version of the Epworth sleepiness scale. Sleep Breath 15(3):377–384

Goldberg D, Bridges K, Duncan-Jones P, Grayson D (1988) Detecting anxiety and depression in general medical settings. BMJ 297(6653):897–899

Lim JY, Lee SH, Cha YS, Park HS, Sunwoo S (2001) Reliability and validity of anxiety screening scale. J Korean Acad Fam Med 22(8):1224–1232

Pignone MP, Gaynes BN, Rushton JL, Burchell CM, Orleans CT, Mulrow CD et al (2002) Screening for depression in adults: a summary of the evidence for the U.S. Preventive services task force. Ann Intern Med 136(10):765–776

Choi HS, Choi JH, Park KH, Joo KJ, Ga H, Ko HJ et al (2007) Standardization of the Korean version of Patient Health Questionnaire-9 as a screening instrument for major depressive disorder. J Korean Acad Fam Med 28(2):114–119

Little RJ, Rubin DB (2014) Statistical analysis with missing data. New York: John Wiley & Sons

Peng KP, Wang SJ (2014) Epidemiology of headache disorders in the Asia-pacific region. Headache 54(4):610–618

Hayley AC, Williams LJ, Kennedy GA, Berk M, Brennan SL, Pasco JA (2014) Prevalence of excessive daytime sleepiness in a sample of the Australian adult population. Sleep Med 15(3):348–354

Vashum KP, McEvoy MA, Hancock SJ, Islam MR, Peel R, Attia JR et al (2015) Prevalence of and associations with excessive daytime sleepiness in an Australian older population. Asia Pac J Public Health 27(2):NP2275–2284

Bartlett DJ, Marshall NS, Williams A, Grunstein RR (2008) Sleep health New South Wales: chronic sleep restriction and daytime sleepiness. Intern Med J 38(1):24–31

Ng TP, Tan WC (2005) Prevalence and determinants of excessive daytime sleepiness in an Asian multi-ethnic population. Sleep Med 6(6):523–529

Joo S, Baik I, Yi H, Jung K, Kim J, Shin C (2009) Prevalence of excessive daytime sleepiness and associated factors in the adult population of Korea. Sleep Med 10(2):182–188

Guilleminault C, Brooks SN (2001) Excessive daytime sleepiness: a challenge for the practising neurologist. Brain 124(Pt 8):1482–1491

Pagel JF (2009) Excessive daytime sleepiness. Am Fam Physician 79(5):391–396

Buysse DJ, Reynolds CF 3rd, Monk TH, Berman SR, Kupfer DJ (1989) The Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index: a new instrument for psychiatric practice and research. Psychiatry Res 28(2):193–213

Perlis ML, Giles DE, Buysse DJ, Tu X, Kupfer DJ (1997) Self-reported sleep disturbance as a prodromal symptom in recurrent depression. J Affect Disord 42(2–3):209–212

Ford DE, Kamerow DB (1989) Epidemiologic study of sleep disturbances and psychiatric disorders. An opportunity for prevention? JAMA 262(11):1479–1484

Wang Y, Xie J, Yang F, Wu S, Wang H, Zhang X et al (2015) Comorbidity of poor sleep and primary headaches among nursing staff in north China. J Headache Pain 16:88

Morgan I, Eguia F, Gelaye B, Peterlin BL, Tadesse MG, Lemma S et al (2015) Sleep disturbances and quality of life in Sub-Saharan African migraineurs. J Headache Pain 16:18

Breslau N, Schultz LR, Stewart WF, Lipton RB, Lucia VC, Welch KM (2000) Headache and major depression: is the association specific to migraine? Neurology 54(2):308–313

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Gallup Korea for providing technical support for the Korean Headache-Sleep Study.

Funding

This Study was Supported by a 2011-Grant from Korean Academy of Medical Sciences.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no conflicting interests.

Authors’ contributions

JYK conceptualized and designed the study, analyzed the data, and wrote the manuscript. SJC conceptualized and designed the study, and wrote the manuscript. JMK conceptualized and collected the data. KIY conceptualized and collected the data. CHY conceptualized and collected the data. MKC conceptualized and designed the study, collected and analyzed the data, and wrote the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Kim, J., Cho, SJ., Kim, WJ. et al. Excessive daytime sleepiness is associated with an exacerbation of migraine: A population-based study. J Headache Pain 17, 62 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1186/s10194-016-0655-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s10194-016-0655-4