Abstract

Introduction

Fatty acids have been implicated in osteoarthritis (OA), yet the mechanism by which fatty acids affect knee structure and consequently the risk of knee OA has not been fully elucidated. Higher intakes of fatty acids have been shown to be associated with the risk of bone marrow lesions (BMLs) in a healthy population. The aim of this study was to examine the association between fatty acid consumption and the incidence of BMLs in healthy middle-aged adults without clinical knee OA.

Methods

Two hundred ninety-seven middle-aged adults without clinical knee OA underwent magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of their dominant knee at baseline. BMLs were assessed. Of the 251 participants with no BMLs in their knee at baseline, 230 underwent MRI of the same knee approximately 2 years later. Intakes of fatty acids were estimated from a food frequency questionnaire.

Results

Increased consumption of saturated fatty acids was associated with an increased incidence of BMLs over 2 years after adjusting for energy intake, age, gender, and body mass index (odds ratio of 2.56 for each standard deviation increase in dietary intake, 95% confidence interval 1.03 to 6.37, P = 0.04). Intake of monounsaturated or polyunsaturated fatty acids was not significantly associated with the incidence of BMLs.

Conclusions

Increased fatty acid consumption may increase the risk of developing BMLs. As subchondral bone is important in maintaining joint integrity and the development of OA, this study suggests that dietary modification of fatty acid intake may be one strategy in the prevention of knee OA which warrants further investigation.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Nutritional factors have been shown to be important in the maintenance of bone and joint health [1]. In particular, fatty acids have been implicated in osteoarthritis (OA) [2, 3]. Elevated levels of fat and n-6 polyunsaturated fatty acids have been found in OA bone [2], whereas n-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids have been shown to alleviate progression of OA through an effect on the metabolism of articular cartilage [3]. Although dietary supplementation with polyunsaturated fatty acids has been shown to decrease bone turnover and increase bone mineral density [4], the finding that a higher ratio of n-6 to n-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids is associated with lower bone mineral density at the hip [5] suggests the important role of relative amounts of these polyunsaturated fatty acids in preserving skeletal integrity in older age.

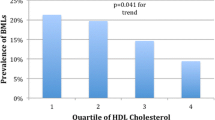

However, the mechanism by which polyunsaturated fatty acids affect the knee structure and consequently the risk of knee OA has not been fully elucidated. We have recently shown that higher intakes of monounsaturated, total, and n-6 polyunsaturated fatty acids were associated with an increased prevalence of bone marrow lesions (BMLs) in a healthy population without clinical knee OA [6]. BMLs have been associated with structural changes of disease severity, including increased cartilage defects, tibial plateau area, loss of cartilage, and joint space narrowing, suggesting that they play a role in the pathogenesis of OA [7–9]. However, there are no longitudinal studies examining the role of fatty acids on incident BMLs in either healthy or OA populations. Therefore, the aim of this study was to examine the association between intakes of different types of fatty acids and the incidence of BMLs in healthy, community-based, middle-aged men and women with no clinical knee OA.

Materials and methods

Subjects

This study was conducted within the Melbourne Collaborative Cohort Study (MCCS), a prospective cohort study of 41,528 Melbourne, Australia residents who were 40 to 69 years old at recruitment (1990 to 1994) [10]. Participants for the current study were recruited from within the MCCS between 2003 and 2004 as previously described [6]. Briefly, participants were eligible if they were between 50 and 79 years old without any of the following exclusion criteria: a clinical diagnosis of knee OA as defined by American College of Rheumatology criteria [11], knee pain lasting for more than 24 hours in the last 5 years, a previous knee injury requiring non-weight-bearing treatment for more than 24 hours or surgery (including arthroscopy), or a history of any form of arthritis diagnosed by a medical practitioner. A further exclusion criterion was a contraindication to magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), including pacemaker, metal sutures, presence of shrapnel or iron filings in the eye, or claustrophobia. The study was approved by The Cancer Council Victoria's Human Research Ethics Committee and the Standing Committee on Ethics in Research Involving Humans of Monash University. All participants gave written informed consent.

Anthropometric and dietary data

Height was measured using a stadiometer with shoes removed. Weight was measured using electronic scales with bulky clothing removed. Body mass index (BMI) (weight/height2, kg/m2) was calculated. At MCCS baseline, questionnaires covered demographic data and diet (via a 121-item food frequency questionnaire developed from a study of weighed food records [12]). Fatty acid intakes were calculated from the food frequency questionnaire using Australian food composition data and were adjusted for energy intake [13].

Magnetic resonance imaging and the measurement of bone marrow lesions

Each subject had an MRI performed on the dominant knee, determined from kicking preference [14], at baseline and approximately 2 years later. Knees were imaged on a 1.5-T whole-body magnetic resonance unit (Philips Medical Systems, Eindhoven, The Netherlands) using a commercial transmit-receive extremity coil, with coronal T2-weighted fat-saturated acquisition as previously described [9]. BMLs were defined as areas of increased signal intensity adjacent to subcortical bone present in either the medial or lateral, distal femur or proximal tibia [9]. Two trained observers, blinded to patient characteristics and sequence of images, together assessed the presence of lesions for each subject. The baseline and follow-up images were assessed unpaired. A lesion was defined as present if it appeared on two or more adjacent slices and encompassed at least one quarter of the width of the tibial or femoral cartilage being examined from coronal images, equivalent to a 'large BML' as described by Felson and colleagues [9]. The reproducibility for determination of BMLs was assessed using 60 randomly selected knee MRIs (κ value 0.88, P < 0.001).

Statistical analyses

The descriptive statistics of the characteristics of study participants were tabulated. Participants with self-reported total energy intakes in the top or bottom 1% of the gender-specific distributions were excluded. A BML was defined as incident if it was present at follow-up in the knees without BMLs at baseline. Logistic regression models were constructed to explore the relationship between fatty acid intakes and incident BMLs after adjusting for potential confounders of age, gender, BMI, and energy intake. Intake of fatty acids was standardised so that the coefficients represent the effect of an increment of one standard deviation (SD) in intake. P values of less than 0.05 were considered to be statistically significant. All analyses were performed using the SPSS statistical package (standard version 15.0.0; SPSS Inc., Cary, NC, USA).

Results

Two hundred ninety-seven subjects entered the study, and four subjects were excluded due to having energy intakes in the top or bottom 1% of the gender-specific distributions. Of the 251 participants who did not have a BML at baseline, 230 (92%) completed the 2-year follow-up. Participants lost to follow-up had a higher BMI (P = 0.04) compared with those who completed follow-up. There were no significant differences in consumption of saturated (P = 0.56), monounsaturated (P = 0.59), or polyunsaturated (P = 0.75) fatty acids between the two groups. Thirty-two subjects developed BMLs at follow-up. Participants who developed BMLs had a higher BMI (mean [SD] 27.9 [5.3] versus 25.4 [3.8] kg/m2, P = 0.02) and higher energy intake-adjusted saturated fatty acid consumption (mean [standard error] 35.7 [1.2] versus 33.0 [0.5] g/day, P = 0.03) when compared with those who did not. There was no significant difference in terms of the energy intake-adjusted consumption of monounsaturated and polyunsaturated fatty acids (Table 1).

Although there was no significant association between fatty acid consumption and the incidence of BMLs over 2 years in univariate analysis, higher consumption of saturated fatty acids was significantly associated with an increased risk of developing BMLs after adjusting for energy intake (Table 2, model 1). For each SD increase in dietary intake of saturated fatty acids, the risk of developing BMLs over 2 years increased 2.62-fold (95% confidence interval [CI] 1.11 to 6.17). This relationship persisted after further adjusting for age, gender, and BMI (odds ratio 2.56, 95% CI 1.03 to 6.37) (Table 2, model 2). No significant association between consumption of monounsaturated or polyunsaturated fatty acids or n-6/n-3 ratio and incident BMLs was found in multivariate analyses (Table 2).

From MCCS baseline when dietary fatty acid intake data were collected during 1990 to 1994 to the inception of current study when baseline MRI was performed in 2003 to 2004, the weight of participants increased by a mean of 2.1 kg (SD 5.2 kg). After adding weight gain to model 2, consumption of saturated fatty acids persisted to be positively associated with incident BMLs (odds ratio 2.54, 95% CI 1.01 to 6.39).

There was no evidence that BMI modified the association between energy intake-adjusted dietary saturated fatty acid consumption and incident BMLs when an interaction term for BMI category × saturated fatty acid intake was included in the logistic model with adjustment for energy intake. The P value was 0.64 when BMI was categorised as less than 25 kg/m2, 25 to 30 kg/m2, and greater than or equal to 30 kg/m2.

Discussion

In a population of healthy middle-aged adults with no clinical knee OA, we found that higher intake of saturated, but not monounsaturated or polyunsaturated, fatty acids or that the n-6/n-3 ratio was associated with an increased likelihood of developing BMLs over 2 years. This is the first longitudinal study presenting a relationship between dietary fatty acid intake and the incidence of BMLs. We have previously shown in a cross-sectional study that increased dietary intake of monounsaturated and n-6, but not n-3, polyunsaturated fatty acids were associated with an increased risk of having BMLs in a healthy population without clinical knee OA [6]. When this population was followed up for 2 years, we found an association between higher saturated fatty acid intake and increased likelihood of developing BMLs over 2 years. Although the mechanism for the discrepancy in terms of the type of fatty acid consumption observed between the previous cross-sectional study and the current prospective cohort study is unclear, the adverse effect of saturated fatty acids on the incidence of BMLs may be attributed to a vascular effect. Saturated fatty acid intake has been associated with atherosclerosis and cardiovascular disease [15]. There are no previous studies identifying a relationship between saturated fatty acid intake and the risk of OA. Recently, it has been suggested that atheromatous vascular disease may be important in the progression of OA [16] and that subchondral ischaemia may be a mechanism by which vascular pathology plays a role in the initiation and/or progression of OA [17]. The findings of this study therefore suggest that vascular disease in subchondral bone may play a role in the pathogenesis of OA via BMLs.

There is mounting evidence that BMLs play a role in the pathogenesis of OA [7–9]. It has been demonstrated that BMLs are associated with the presence of cartilage defects in healthy asymptomatic populations with no history of significant knee pain or injury and that risk factors for OA such as age, height, and BMI also affect the prevalence of BMLs [18, 19]. Moreover, the presence of BMLs predicts the progression of cartilage defects and loss of cartilage volume over 2 years in longitudinal studies [20, 21]. These findings suggest that BMLs may be associated with an increased risk of knee OA. This study demonstrates an increased incidence of BMLs associated with increased saturated fatty acid intake in a healthy population and suggests that modifying diet may be one such way to reduce the development and subsequent burden of OA.

This study has a number of potential limitations. First, this study examined a healthy, community-based population selected on the criterion of having no knee pain or injury and therefore the results may not be generalisable to symptomatic populations or people who have injured their knees. However, the findings of our study can be generalised to populations that would be targeted by primary prevention strategies. Second, whilst the dietary intake of fatty acids was measured in a valid fashion [22], this was based on a single measure of nutrient intakes 10 years earlier. Although significant underreporting of fat intake is likely [23], absolute intake of dietary fat tends to remain stable [24, 25]. While nutritional data collected 10 years earlier may have resulted in some misclassification of exposure, such misclassification is likely to have been non-differential in relation to knee structure since only subjects with no history of knee symptoms or injury were included, thereby tending to underestimate the strength of any observed associations. In the current study, we did not measure knee alignment, which has been shown to be associated with BMLs [9].

Conclusions

The findings of this study suggest that increased fatty acid consumption may increase the risk of developing BMLs in a healthy population without clinical knee OA. As subchondral bone is important in maintaining joint integrity and the development of OA, this study suggests that dietary modification of fatty acid intake may be one strategy in the prevention of knee OA which warrants further investigation.

Abbreviations

- BMI:

-

body mass index

- BML:

-

bone marrow lesion

- CI:

-

confidence interval

- MCCS:

-

Melbourne Collaborative Cohort Study

- MRI:

-

magnetic resonance imaging

- OA:

-

osteoarthritis

- SD:

-

standard deviation.

References

Goggs R, Vaughan-Thomas A, Clegg PD, Carter SD, Innes JF, Mobasheri A, Shakibaei M, Schwab W, Bondy CA: Nutraceutical therapies for degenerative joint diseases: a critical review. Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr. 2005, 45: 145-164. 10.1080/10408690590956341.

Plumb MS, Aspden RM: High levels of fat and (n-6) fatty acids in cancellous bone in osteoarthritis. Lipids Health Dis. 2004, 3: 12-10.1186/1476-511X-3-12.

Curtis CL, Rees SG, Little CB, Flannery CR, Hughes CE, Wilson C, Dent CM, Otterness IG, Harwood JL, Caterson B: Pathologic indicators of degradation and inflammation in human osteoarthritic cartilage are abrogated by exposure to n-3 fatty acids. Arthritis Rheum. 2002, 46: 1544-1553. 10.1002/art.10305.

Weaver CM, Peacock M, Johnston CC: Adolescent nutrition in the prevention of postmenopausal osteoporosis. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1999, 84: 1839-1843. 10.1210/jc.84.6.1839.

Weiss LA, Barrett-Connor E, von Muhlen D: Ratio of n-6 to n-3 fatty acids and bone mineral density in older adults: the Rancho Bernardo Study. Am J Clin Nutr. 2005, 81: 934-938.

Wang Y, Wluka AE, Hodge AM, English DR, Giles GG, O'Sullivan R, Cicuttini FM: Effect of fatty acids on bone marrow lesions and knee cartilage in healthy, middle-aged subjects without clinical knee osteoarthritis. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2008, 16: 579-583. 10.1016/j.joca.2007.09.007.

Phan CM, Link TM, Blumenkrantz G, Dunn TC, Ries MD, Steinbach LS, Majumdar S: MR imaging findings in the follow-up of patients with different stages of knee osteoarthritis and the correlation with clinical symptoms. Eur Radiol. 2006, 16: 608-618. 10.1007/s00330-005-0004-5.

Sowers MF, Hayes C, Jamadar D, Capul D, Lachance L, Jannausch M, Welch G: Magnetic resonance-detected subchondral bone marrow and cartilage defect characteristics associated with pain and X-ray-defined knee osteoarthritis. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2003, 11: 387-393. 10.1016/S1063-4584(03)00080-3.

Felson DT, McLaughlin S, Goggins J, LaValley MP, Gale ME, Totterman S, Li W, Hill C, Gale D: Bone marrow edema and its relation to progression of knee osteoarthritis. Ann Intern Med. 2003, 139: 330-336.

Giles GG, English DR: The Melbourne Collaborative Cohort Study. IARC Sci Publ. 2002, 156: 69-70.

Altman R, Asch E, Bloch D, Bole G, Borenstein D, Brandt K, Christy W, Cooke TD, Greenwald R, Hochberg M, Howell D, Kaplan D, Koopman W, Longley S, Mankin H, McShane DJ, Medsger T, Meenan R, Mikkelsen W, Moskowitz R, Murphy W, Rothschild B, Segal M, Sokoloff L, Wolfe F: Development of criteria for the classification and reporting of osteoarthritis. Classification of osteoarthritis of the knee. Diagnostic and Therapeutic Criteria Committee of the American Rheumatism Association. Arthritis Rheum. 1986, 29: 1039-1049. 10.1002/art.1780290816.

Ireland P, Jolley D, Giles G: Development of the Melbourne FFQ: a food frequency questionnaire for use in an Australian prospective study involving and ethnically diverse cohort. Asia Pac J Clin Nutr. 1994, 3: 19-31.

RMIT Lipid Research Group: Fatty acid compositional database. 2001, Brisbane, Australia: Xyris Software

Rizzardo M, Wessel J, Bay G: Eccentric and concentric torque and power of the knee extensors of females. Can J Sport Sci. 1988, 13: 166-169.

Bemelmans WJ, Lefrandt JD, Feskens EJ, Broer J, Tervaert JW, May JF, Smit AJ: Change in saturated fat intake is associated with progression of carotid and femoral intima-media thickness, and with levels of soluble intercellular adhesion molecule-1. Atherosclerosis. 2002, 163: 113-120. 10.1016/S0021-9150(01)00747-X.

Conaghan PG, Vanharanta H, Dieppe PA: Is progressive osteoarthritis an atheromatous vascular disease?. Ann Rheum Dis. 2005, 64: 1539-1541. 10.1136/ard.2005.039263.

Findlay DM: Vascular pathology and osteoarthritis. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2007, 46: 1763-1768. 10.1093/rheumatology/kem191.

Guymer E, Baranyay F, Wluka AE, Hanna F, Bell RJ, Davis SR, Wang Y, Cicuttini FM: A study of the prevalence and associations of subchondral bone marrow lesions in the knees of healthy, middle-aged women. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2007, 15: 1437-1442. 10.1016/j.joca.2007.04.010.

Baranyay FJ, Wang Y, Wluka AE, English DR, Giles GG, O'Sullivan R, Cicuttini FM: Association of bone marrow lesions with knee structures and risk factors for bone marrow lesions in the knees of clinically healthy, community-based adults. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2007, 37: 112-118. 10.1016/j.semarthrit.2007.01.008.

Wluka AE, Wang Y, Davies-Tuck M, English DR, Giles GG, Cicuttini FM: Bone marrow lesions predict progression of cartilage defects and loss of cartilage volume in healthy middle-aged adults without knee pain over 2 yrs. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2008, 47: 1392-1396. 10.1093/rheumatology/ken237.

Wluka AE, Hanna F, Davies-Tuck M, Wang Y, Bell RJ, Davis SR, Adams J, Cicuttini FM: Bone marrow lesions predict increase in knee cartilage defects and loss of cartilage volume in middle-aged women without knee pain over 2 years. Ann Rheum Dis. 2009, 68: 850-855. 10.1136/ard.2008.092221.

Hodge AM, Simpson JA, Gibson RA, Sinclair AJ, Makrides M, O'Dea K, English DR, Giles GG: Plasma phospholipid fatty acid composition as a biomarker of habitual dietary fat intake in an ethnically diverse cohort. Nutr Metab Cardiovasc Dis. 2007, 17: 415-426. 10.1016/j.numecd.2006.04.005.

Astrup A: The American paradox: the role of energy-dense fat-reduced food in the increasing prevalence of obesity. Curr Opin Clin Nutr Metab Care. 1998, 1: 573-577. 10.1097/00075197-199811000-00016.

Sigman-Grant M: Can you have your low-fat cake and eat it too? The role of fat-modified products. J Am Diet Assoc. 1997, 97: S76-81. 10.1016/S0002-8223(97)00736-0.

Allred JB: Too much of a good thing? An overemphasis on eating low-fat foods may be contributing to the alarming increase in overweight among US adults. J Am Diet Assoc. 1995, 95: 417-418. 10.1016/S0002-8223(95)00111-5.

Acknowledgements

The Melbourne Collaborative Cohort Study recruitment was funded by VicHealth and The Cancer Council Victoria. This study was funded by a program grant from the National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC) (209057) and was further supported by infrastructure provided by The Cancer Council Victoria. We would like to acknowledge the NHMRC (project grant 334150), Colonial Foundation, and Shepherd Foundation for support. YW and AEW are the recipients of NHMRC Public Health (Australia) Fellowships (NHMRC 465142 and 317840, respectively). MLD-T is the recipient of Australian Postgraduate Award PhD Scholarship. We would especially like to thank the study participants, who made this study possible.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors' contributions

YW participated in the design of the study, performed the statistical analysis and the interpretation of data, and drafted the manuscript. MLD-T performed the measurement of bone marrow lesions, participated in the statistical analysis and the interpretation of data, and drafted the manuscript. AEW participated in the interpretation of data and reviewed the manuscript. AF helped in the statistical analysis and reviewed the manuscript. DRE and GGG participated in the design of the study and the acquisition of data and reviewed the manuscript. RO provided technical support and reviewed the manuscript. FMC participated in the design of the study, helped in the interpretation of data, and reviewed the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Yuanyuan Wang, Miranda L Davies-Tuck contributed equally to this work.

Rights and permissions

This article is published under an open access license. Please check the 'Copyright Information' section either on this page or in the PDF for details of this license and what re-use is permitted. If your intended use exceeds what is permitted by the license or if you are unable to locate the licence and re-use information, please contact the Rights and Permissions team.

About this article

Cite this article

Wang, Y., Davies-Tuck, M.L., Wluka, A.E. et al. Dietary fatty acid intake affects the risk of developing bone marrow lesions in healthy middle-aged adults without clinical knee osteoarthritis: a prospective cohort study. Arthritis Res Ther 11, R63 (2009). https://doi.org/10.1186/ar2688

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/ar2688