Abstract

Background

Advanced cancer patients experience considerable symptoms, problems, and needs. Early referral of these patients to specialised palliative care (SPC) could improve their symptoms and problems.

The Danish Palliative Care Trial (DanPaCT) investigates whether patients with metastatic cancer, who report palliative needs in a screening, will benefit from being referred to ‘early SPC’.

Methods/Design

DanPaCT is a clinical, multicentre, parallel-group superiority trial with balanced randomisation (1:1). The planned sample size is 300 patients. Patients are randomised to specialised palliative care (SPC) plus standard treatment versus standard treatment. Consecutive patients from oncology departments are screened for palliative needs with a questionnaire if they: a) have metastatic cancer; b) are 18 years or above; and c) have no prior contact with SPC. Patients with palliative needs (i.e. symptoms/problems exceeding a certain threshold) according to the questionnaire are eligible. The primary outcome is the change in the patients’ primary need (the most severe symptom/problem measured with the European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer Quality of Life Questionnaire (EORTC QLQ-C30)). Secondary outcomes are other symptoms/problems (EORTC QLQ-C30), satisfaction with health care (FAMCARE P-16), anxiety and depression (the Hospital Anxiety and Depression scale), survival, and health care costs.

Discussion

Only few trials have investigated the effects of SPC. To our knowledge DanPaCT is the first trial to investigate screening based ‘early SPC’ for patients with a broad spectrum of cancer diagnosis.

Trial registration

Current controlled Trials NCT01348048

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

The aim of palliative care is to relieve suffering and improve quality of life in patients with a life-threatening disease [1]. Palliative care can be divided into basic palliative care provided by general practitioners, home-care services, and hospitals, and specialised palliative care (SPC) which is offered by palliative care teams, departments of palliative medicine, and hospices [2].

In 2011, 38% of patients dying from cancer in Denmark had been in contact with SPC [2]. Their median survival from first contact with SPC was six weeks [2]. Our recent, nation-wide study showed that large proportions of advanced cancer patients not in contact with SPC had symptoms and problems such as pain, fatigue, and depression [3, 4]. One possible solution to the inadequate management of symptoms could be the referral of these patients to SPC at an earlier time in their disease trajectory (‘early SPC’).

A recent randomised trial investigated ‘early SPC’ plus standard treatment versus standard treatment alone [5–7]. It showed that patients newly diagnosed with metastatic lung cancer who were randomised to SPC plus standard treatment obtained better quality of life, less depression, and longer survival than patients receiving standard treatment. Thus, the trial provided preliminary evidence that ‘early SPC’ seem beneficial in lung cancer. However, this was a single-centre U.S.A. trial assessing a small and selected group of patients. We wanted to assess the effects of ‘early SPC’ in a Danish setting and in a population with various cancer diagnoses. Furthermore, not all patients with metastatic cancer need SPC and therefore including patients with no palliative needs may ‘dilute’ possible positive effects of ‘early SPC’. Accordingly, we therefore want to investigate whether patients with metastatic cancer who report palliative needs (symptoms and problems) in a screening will benefit from being referred to SPC.

The aim of the present paper is to describe the Danish Palliative Care Trial (DanPaCT) protocol.

Methods and design

Trial design

The trial is a clinical, multicentre, parallel-group superiority trial with balanced randomisation (1:1) conducted at six Danish SPC centres. The protocol has been approved by the local regional ethics committee (the Ethics Committee for the Capital Region, Denmark; journal number H-3-2010-144) and registered at www.clinicaltrials.gov (NCT01348048).

Setting

Patients from departments of oncology are randomised to SPC plus standard care versus standard care. Patients are recruited at the following hospitals: Copenhagen University Hospital (Rigshospitalet), Aarhus University Hospital, Odense University Hospital, Herning Hospital, and Vejle Hospital. Information about the six SPC centres can be seen in Table 1.

Patient inclusion and exclusion criteria

Patients in contact with the oncology departments who have cancer stage four according to the ‘TNM’ (TNM stands for Tumor, Node, Metastases) classification [8] or cancer in the central nervous system grade three or four, are at least 18 years, live in the area of one of the participating SPC centres, and who have not had contact with an SPC during the previous year receive a screening questionnaire. If, according to their answers in the questionnaire, they have a palliative need and four additional symptoms (see definition below) they are informed about the trial and invited to participate. Patients who provide informed consent are randomised. Patients are excluded from the trial if they cannot understand Danish well enough to fill in a questionnaire or are considered incapable of complying with the trial protocol.

Screening: assessment of palliative needs and additional symptoms

Patients are screened with the European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer Quality of Life Questionnaire (EORTC QLQ-C30) [9].

The EORTC QLQ-C30 [9] assesses health-related quality of life and consists of nine multi-item scales measuring: physical function, role function, emotional function, cognitive function, social functioning, global health status/quality of life, fatigue, nausea and vomiting, and pain, and six single-item scales: dyspnoea, insomnia, lack of appetite, constipation, diarrhoea and financial difficulties.

Patients are defined as having a palliative need and four additional symptoms (and are thus eligible for the trial) if they:

● Score at least 50% of the score corresponding to maximal symptom burden or maximally reduced functioning on at least one of the following scales in EORTC QLQ-C30: physical function, role function, emotional function, nausea and vomiting, pain, dyspnoea, or lack of appetite; AND

● Have four additional symptoms (defined as EORTC QLQ-C30 scale score of at least 33% of the score corresponding to maximal symptom burden or maximally reduced functioning) out of the 14 EORTC QLQ-C30 scales (global health status/quality of life excluded).

Randomisation

Central randomisation via telephone is carried out by the Copenhagen Trial Unit (CTU), which is independent of the trial administration office. The allocation sequence is computer-generated 1:1 with varying block size and is kept unknown for all investigators. Randomisation is stratified by the variable ’primary need’ (see description in the section ‘Outcomes’).

Assessments and questionnaires

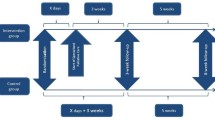

All randomised patients are assessed with a questionnaire (see Figure 1): a) at baseline (the screening); b) after a 3-week follow-up period; and c) after an 8-week follow-up period.

The questionnaires include EORTC QLQ-C30 (described in the section on ‘screening’), the FAMCARE-p16 questionnaire [10] and the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HAD scale) [11]. FAMCARE-p16 assesses advanced cancer patients’ satisfaction with the health care system. The questionnaire includes several items that address key areas of palliative care. It uses 5-point Likert scales where 1=‘very satisfied’, 2=‘satisfied’, 3=‘undecided’, 4=‘dissatisfied’ and 5=‘very dissatisfied’. The patients are asked to rate the care they received within the previous month. In addition four items measuring satisfaction were developed for this particular trial.

The HAD [11] scale assesses anxiety and depression and was developed for people with a somatic disease. The questionnaire has been used in many studies of advanced cancer patients, and its validity and reliability has been tested on several occasions with a generally positive conclusion [12].

Finally, we included six additional newly developed items to measure pain, three items measuring appetite loss, and three items about dyspnoea. These items were selected from the item banks of the EORTC Computerised Adaptive Testing Project [13, 14] and will be used in sensitivity analysis and subsequent methodological analyses only.

Three months after end of the intervention information about death, use of health services and treatments are retrieved from registers by investigators who are blinded and not aware of treatment allocation.

Clinical data is extracted from the medical records regarding primary tumour, sex, age, stage of cancer according to the TNM system, time of primary diagnosis, and treatment status.

To describe the interventions given and the ‘palliative activity’ in both groups all treatments and contacts with the health care system are registered. This is done by reviewing the medical records from the time of randomisation until the 8-week follow-up.

Outcomes

The primary outcome is estimated as the difference between the intervention and the control group in the change from baseline to the weighted mean of the 3- and 8-week follow-up measured as area under the curve (AUC) for the EORTC QLQ-C30 scale score that constitutes the primary need. The primary need is defined as the palliative need having the highest intensity at baseline according to the EORTC QLQ-C30. Seven different palliative needs (listed in the section on screening) are considered when defining the primary need.

Secondary outcomes, estimated in the same way, are a) the remaining symptoms and problems measured by the EORTC QLQ-C30 (14 scales), b) anxiety and depression measured by the HAD Scale c) the patients’ evaluation of treatment and care provided by the health care system measured by the FAMCARE-p16, d) survival, and e) economical consequences per week from the start of the trial to minimum three months after the end of the intervention.

Sample size estimation

We know from previous studies (unpublished data) that the standard deviation (SD) for a difference between repeated measurements (three weeks apart) in the EORTC QLQ-C30 is 15 to 22 points. Therefore, we assume that the primary outcome has an SD of 20 points in the present trial. We wish to be able to detect a difference of 7.5 points (a difference between 5 and 10 is normally judged clinically significant [15]). With a risk of type I error of 0.05 and type II error of 0.10 we need 150 patients in each intervention group, i.e., a total of 300 patients, and 50 from each centre.

Plan of analysis

Analyses will be made using SAS statistical software version 9 [16]. The primary analysis will be based on the intention-to-treat principle. If there are more than 5% missing answers we will use multiple imputations with the following variables in our model: age, sex, diagnosis, cancer stage, and The World Health Organisations(WHO) performance score.

Analyses will be made as multiple regressions. The primary analysis of all outcomes will be adjusted for the stratification variable, the patient’s ‘primary need’. Sensitivity analyses will further be adjusted for WHO performance status, and ‘centre’. If there is an imbalance in the two treatments groups we shall further consider adjusting for gender, age, cancer stage, diagnosis, co-morbidity, treatment status and education which may have a prognostic value [17, 18].

Blinding

Allocation status cannot be blinded for the participants and trial personnel. However, concealment of allocation is carefully maintained during retrieval of outcome information from national registers. Further, all statistical analyses will be carried out blinded to intervention with the two groups coded as, e.g., A and B. Two conclusions will be drawn, one assuming A is the experimental group and B is the control group, and one assuming the opposite. After this, the blind will be broken.

Ethics

The justification for carrying out the trial is the sparse evidence concerning the beneficial and harmful effects of ‘early SPC’. In addition, patients randomised to standard treatment in this trial receive the same treatment as they would have had it not been for this trial. Some of these patients may seek referral to SPC and of course, this will be registered but not prevented.

Discussion

Few randomised clinical trials have investigated the effect of SPC and thus, the evidence regarding SPC is sparse [5, 19–29]. DanPaCT is a randomised multicentre trial including patients with advanced cancers from multiple organs. To our knowledge it is the first trial to investigate ‘early SPC’ for patients with a broad spectrum of cancer diagnosis, and the first trial to investigate screening-based referral to SPC. In addition it is the first to provide detailed information about the specific interventions given by the SPC centres; a knowledge that has been requested [30].

In DanPaCT, the primary outcome is tailored to the patient by being the patient’s most pronounced symptom/problem (‘primary need’). For some patients, the primary outcome is pain, for others it is appetite loss. The strength of this approach is that the primary outcome is relevant for all patients, and that it takes into account the multidimensionality of palliative care without summing up the different symptoms/problems, which may lead to dilution of the measurement of effect.

The treatment allocation cannot be blinded for participants and staff, which is of course a limitation [31, 32]. This lack of blinding of the treatment after allocation may have several consequences. It is possible that patients in the SPC group will receive less attention from the oncology departments. To determine whether this is the case, the two groups’ number of contacts with the oncology departments will be assessed and compared. Although we consider it unlikely, it is also possible that patients in the SPC group will receive a better SPC treatment than patients receiving usual care, and it is possible that patients in the SPC group will underreport their symptoms at follow-up. However, the patients are not informed about the primary outcome of the trial. Further, assessment of survival and health economics will be based on registry data and hence, blinded to intervention. In addition, the randomisation will be performed centrally and allocation carefully concealed to the project nurses in order to avoid selection bias, and data-analysts will be blinded to intervention [31, 32].

The trial does not include all relevant palliative needs (e.g., existential and spiritual needs). In addition, patients with metastatic cancer constitute a heterogeneous group, and SPC may work better for patients with some primary diagnoses than for others, and this could weaken the power of our trial. It is also possible that the various SPC centres are better at treating different symptoms, and that a high effect from one SPC centre is weakened by the others. However, the heterogeneity of patients and centres increase the generalisability of our results.

When the trial started we had different inclusion criteria from what has been presented here. Originally, the patients needed to have two palliative needs instead of only one, and the definition of palliative need was originally stricter (in order to have a palliative need the patients had to consider the symptom to be a problem and have a need for help with the symptom). However, after the first two months of the trial, we realised that our initial inclusion criteria was too strict. Out of the first 168 patients completing a screening questionnaire, only eight were randomised. Therefore we changed the inclusion criteria in order to make a larger proportion of patients eligible. It is the revised and final inclusion criteria which are presented in this paper. The change was approved by the local regional ethics committee, the funding body and reported to clinicaltrials.gov.

Conclusion

The DanPaCT trial aims at investigating whether patients with metastatic cancer who report palliative needs in a screening will benefit from being referred to ‘early SPC’. We also study the economical and survival consequences of such a referral.

References

World Health Organization: Policies and managerial guidelines. 2002, Geneva: WHO, http://www.who.int/cancer/publications/nccp2002/en/index.html.

Groenvold M, Hansen MB, Rasmussen M: [Årsrapport for dansk palliativ database 2011]. Report from the Danish palliative database 2011. 2012, Copenhagen, http://dmcgpal.dk/files/dpd_aarsrapport_2011.pdf.

Johnsen AT, Petersen MA, Pedersen L, Groenvold M: Symptoms and problems in a nationally representative sample of advanced cancer patients. Palliat Med. 2009, 23: 491-501. 10.1177/0269216309105400.

Johnsen AT, Petersen MA, Pedersen L, Houmann LJ, Groenvold M: Do advanced cancer patients in Denmark receive the help they need? A nationally representative survey of the need related to 12 frequent symptoms/problems. Psychooncology. 2013, 22: 1724-1730. 10.1002/pon.3204.

Temel JS, Greer JA, Muzikansky A, Gallagher ER, Admane S, Jackson VA, Dahlin CM, Blinderman CD, Jacobsen J, Pirl WF, Billings JA, Lynch TJ: Early palliative care for patients with metastatic non-small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2010, 363: 733-742. 10.1056/NEJMoa1000678.

Pirl WF, Greer JA, Traeger L, Jackson V, Lennes IT, Gallagher ER, Perez-Cruz P, Heist RS, Temel JS: Depression and survival in metastatic non-small-cell lung cancer: effects of early palliative care. J Clin Oncol. 2012, 30: 1310-1315. 10.1200/JCO.2011.38.3166.

Greer JA, Pirl WF, Jackson VA, Muzikansky A, Lennes IT, Heist RS, Gallagher ER, Temel JS: Effect of early palliative care on chemotherapy use and end-of-life care in patients with metastatic non-small-cell lung cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2012, 30: 394-400. 10.1200/JCO.2011.35.7996.

American Joint Committee on Cancer: AJCC - cancer staging manual. 2010, Chicago: Springer, http://www.cancerstaging.org/, 7.

Aaronson NK, Ahmedzai S, Bergman B, Bullinger M, Cull A, Duez NJ, Filiberti A, Flechtner H, Fleishman SB, Dehaes JCJM, Kaasa S, Klee M, Osoba D, Razavi D, Rofe PB, Schraub S, Sneeuw K, Sullivan M, Takeda F: The european-organization-for-research-and-treatment-of-cancer Qlq-C30 - a quality-of-life instrument for Use in international clinical-trials in oncology. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1993, 85: 365-376. 10.1093/jnci/85.5.365.

Lo C, Burman D, Rodin G, Zimmermann C: Measuring patient satisfaction in oncology palliative care: psychometric properties of the FAMCARE-patient scale. Qual Life Res. 2009, 18: 747-752. 10.1007/s11136-009-9494-y.

Zigmond AS, Snaith RP: The hospital anxiety and depression scale. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1983, 67: 361-370. 10.1111/j.1600-0447.1983.tb09716.x.

Herrmann C: International experiences with the hospital anxiety and depression scale–a review of validation data and clinical results. J Psychosom Res. 1997, 42: 17-41. 10.1016/S0022-3999(96)00216-4.

Petersen MA, Groenvold M, Aaronson NK, Chie WC, Conroy T, Costantini A, Fayers P, Helbostad J, Holzner B, Kaasa S, Singer S, Velikova G, Young T: Development of computerized adaptive testing (CAT) for the EORTC QLQ-C30 physical functioning dimension. Qual Life Res. 2011, 20: 479-490. 10.1007/s11136-010-9770-x.

Petersen MA, Groenvold M, Aaronson NK, Chie WC, Conroy T, Costantini A, Fayers P, Helbostad J, Holzner B, Kaasa S, Singer S, Velikova G, Young T: Development of computerised adaptive testing (CAT) for the EORTC QLQ-C30 dimensions - general approach and initial results for physical functioning. Eur J Cancer. 2010, 46: 1352-1358. 10.1016/j.ejca.2010.02.011.

King MT: The interpretation of scores from the EORTC quality of life questionnaire QLQ-C30. Qual Life Res. 1996, 5: 555-567. 10.1007/BF00439229.

SAS Institute Inc: SAS/STAT 9.1 user’s guide. 2004, Cary, NC: SAS Institute Inc, http://support.sas.com/documentation/onlinedoc/stat/chapters91.html.

Jordhoy MS, Fayers P, Loge JH, Saltnes T, Ahlner-Elmqvist M, Kaasa S: Quality of life in advanced cancer patients: the impact of sociodemographic and medical characteristics. Br J Cancer. 2001, 85: 1478-1485. 10.1054/bjoc.2001.2116.

Parker PA, Baile WF, de Moor C, Cohen L: Psychosocial and demographic predictors of quality of life in a large sample of cancer patients. Psychooncology. 2003, 12: 183-193. 10.1002/pon.635.

Brumley R, Enguidanos S, Jamison P, Seitz R, Morgenstern N, Saito S, McIlwane J, Hillary K, Gonzalez J: Increased satisfaction with care and lower costs: results of a randomized trial of in-home palliative care. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2007, 55: 993-1000. 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2007.01234.x.

Rabow MW, Dibble SL, Pantilat SZ, McPhee SJ: The comprehensive care team: a controlled trial of outpatient palliative medicine consultation. Arch Intern Med. 2004, 164: 83-91. 10.1001/archinte.164.1.83.

Jordhoy MS, Fayers P, Loge JH, Ahlner-Elmqvist M, Kaasa S: Quality of life in palliative cancer care: results from a cluster randomized trial. J Clin Oncol. 2001, 19: 3884-3894.

Hughes SL, Cummings J, Weaver F, Manheim L, Braun B, Conrad K: A randomized trial of the cost effectiveness of VA hospital-based home care for the terminally ill. Health Serv Res. 1992, 26: 801-817.

Hanks GW, Robbins M, Sharp D, Forbes K, Done K, Peters TJ, Morgan H, Sykes J, Baxter K, Corfe F, Bidgood C: The imPaCT study: a randomised controlled trial to evaluate a hospital palliative care team. Br J Cancer. 2002, 87: 733-739. 10.1038/sj.bjc.6600522.

McWhinney IR, Bass MJ, Donner A: Evaluation of a palliative care service: problems and pitfalls. BMJ. 1994, 309: 1340-1342. 10.1136/bmj.309.6965.1340.

McCorkle R, Benoliel JQ, Donaldson G, Georgiadou F, Moinpour C, Goodell B: A randomized clinical trial of home nursing care for lung cancer patients. Cancer. 1989, 64: 1375-1382. 10.1002/1097-0142(19890915)64:6<1375::AID-CNCR2820640634>3.0.CO;2-6.

Zimmer JG, Groth-Juncker A, McCusker J: A randomized controlled study of a home health care team. Am J Public Health. 1985, 75: 134-141. 10.2105/AJPH.75.2.134.

Kane RL, Wales J, Bernstein L, Leibowitz A, Kaplan S: A randomised controlled trial of hospice care. Lancet. 1984, 1: 890-894.

Edmonds P, Karlsen S, Khan S, Addington-Hall J: A comparison of the palliative care needs of patients dying from chronic respiratory diseases and lung cancer. Palliat Med. 2001, 15: 287-295. 10.1191/026921601678320278.

Higginson IJ, Hart S, Burman R, Silber E, Saleem T, Edmonds P: Randomised controlled trial of a new palliative care service: compliance, recruitment and completeness of follow-up. BMC Palliat Care. 2008, 7: 7-10.1186/1472-684X-7-7.

Temel JS, Jackson VA, Billings JA, Dahlin C, Block SD, Buss MK, Ostler P, Fidias P, Muzikansky A, Greer JA, Pirl WF, Lynch TJ: Phase II study: integrated palliative care in newly diagnosed advanced non-small-cell lung cancer patients. J Clin Oncol. 2007, 25: 2377-2382. 10.1200/JCO.2006.09.2627.

Wood L, Egger M, Gluud LL, Schulz KF, Juni P, Altman DG, Gluud C, Martin RM, Wood AJ, Sterne JA: Empirical evidence of bias in treatment effect estimates in controlled trials with different interventions and outcomes: meta-epidemiological study. BMJ. 2008, 336: 601-605. 10.1136/bmj.39465.451748.AD.

Savovic J, Jones HE, Altman DG, Harris RJ, Juni P, Pildal J, Als-Nielsen B, Balk EM, Gluud C, Gluud LL, Ioannidis JP, Schulz KF, Beynon R, Welton NJ, Wood L, Moher D, Deeks JJ, Sterne JA: Influence of reported study design characteristics on intervention effect estimates from randomized, controlled trials. Ann Intern Med. 2012, 157: 429-438.

Pre-publication history

The pre-publication history for this paper can be accessed here:http://www.biomedcentral.com/1472-684X/12/37/prepub

Funding

This work was funded by The Danish foundation TrygFonden [journal number 7-10-0838A] and the Danish Cancer Society [journal number R16-A695].

Acknowledgements

We wish to thank the following project nurses for collecting the data: Agnethe Fløe Nielsen and Sine Jürgensen Stamm Mikkelsen, Aarhus University Hospital; Lone Thorup Røge and Grethe Christensen, Herning Sygehus; Berit Schmidt Bigum and Kristina Olesen, Vejle Sygehus; Kirsten Rasmussen, Line Haslund and Merethe Martin, Odense University Hospital; and Katrine Eldrup, Helena Lindholm, Louise Christoffersen and Lisbeth Grave Bendixen, Copenhagen University Hospital (Rigshospitalet). Furthermore, we wish to thank the palliative care teams for participating in the trial. Last, but not least, we wish to thank the patients for their participation.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

ATJ, AD, TBV, JL, PS, CG, MAN, MAP, LEL, LP, PF, IJH, MG took part in designing the trial. JL, CG, MAP, PF with special competence in RCT and/or statistical analysis, and ATJ, AD, TBV, PS, MAN, LEL, LP, IJH, MG with special competence in palliative care. AD, TBV, PS, MAN, LEL, LP, MG are clinical investigators and in charge of the data collection, and ASS helped collect data. ATJ was project coordinator and MG received the funding for the study. ATJ drafted the paper and all authors read, amended and approved the final manuscript.

Authors’ original submitted files for images

Below are the links to the authors’ original submitted files for images.

Rights and permissions

This article is published under an open access license. Please check the 'Copyright Information' section either on this page or in the PDF for details of this license and what re-use is permitted. If your intended use exceeds what is permitted by the license or if you are unable to locate the licence and re-use information, please contact the Rights and Permissions team.

About this article

Cite this article

Johnsen, A.T., Damkier, A., Vejlgaard, T.B. et al. A randomised, multicentre clinical trial of specialised palliative care plus standard treatment versus standard treatment alone for cancer patients with palliative care needs: the Danish palliative care trial (DanPaCT) protocol. BMC Palliat Care 12, 37 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1186/1472-684X-12-37

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/1472-684X-12-37