Abstract

Background

To investigate the association between dietary components and development of chronic diabetic complications, the dietary evaluation should include a long period, months or years. The present manuscript aims to develop a quantitative food frequency questionnaire (FFQ) and a portfolio with food photos to assess the usual intake pattern of Brazilian patients with type 2 diabetes to be used in future studies.

Methods

Dietary data using 3-day weighed diet records (WDR) from 188 outpatients with type 2 diabetes were used to construct the list of usually consumed foods. Foods were initially clustered into eight groups: “cereals, tubers, roots, and derivatives”; “vegetables and legumes”; “fruits”; “beans”; “meat and eggs”; “milk and dairy products”; “oils and fats”, and “sugars and sweets”. The frequency of food intake and the relative contribution of each food item to the total energy and nutrient intakes were calculated. Portion sizes were determined according to the 25th, 50th, 75th, and 95th percentiles of intake for each food item.

Results

A total of 62 food items were selected based on the 3-day WDR and another 27 foods or how they are prepared and nine beverages were included after the expert examination. Also, a portfolio with food photos of each included food item and portion sizes was made to assist the patients in identifying the consumed portion.

Conclusions

We developed a practical quantitative FFQ and portfolio with photos of 98 food items covering those most commonly consumed in the past 12 months, to assess the usual diet pattern of patients with type 2 diabetes in Southern Brazil.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

The field of nutritional epidemiology has been developed because of an interest in the concept that aspects of diet may influence the occurrence of human disease [1]. In the case of patients with diabetes, dietary advice and assessment of compliance with these recommendations are important for achieving metabolic goals, especially glycemic control [2].

There are several methods for the assessment of food and nutrient consumption as well as energy intake, including 24-hour recall, food records, food frequency questionnaire (FFQ), and biomarkers [3]. To investigate the association between dietary components and development of chronic diabetic complications, the dietary evaluation should include a long period, months or years, as is the case of FFQ. To date, four FFQs involving patients with diabetes have been validated and published in specific populations: Australian [4], Japanese [5], Malian [6], and Korean [7]; however, none was made for the Brazilian population. In fact, the FFQ should represent regional habits and the accuracy of such data needs to take this into account [8].

In drawing up an FFQ, careful attention must be given to the choice of foods, the clearness of the questions, and the format of the frequency response section. In addition, the choice of foods, especially if the FFQ is constructed to also include quantitative or semi-quantitative dietary evaluation, should be based on an accurate dietary tool [9]. In this way, the present manuscript aims to create an FFQ and a portfolio with food photos to assess the usual intake pattern of Brazilian patients with diabetes to be used in future studies.

Methods

Study population

Patients were identified belonged to the Group of Nutrition in Endocrinology (GNE), a cohort of outpatients with type 2 diabetes in southern Brazil [10]. The GNE study was designed to evaluate possible associations of dietary factors with chronic complications of diabetes. From a previously constructed database of patients with type 2 diabetes [11] data from consecutive registered patients who reported a plausible ratio of protein intake estimated from the 3-day weighed diet records (WDR) to protein intake from urinary nitrogen [12] were selected. The acceptable ratio between the two protein intake estimates ranged from 0.79 to 1.26 [12]. An equal seasonal distribution (1:1:1:1 spring, summer, autumn, and winter) and the same gender proportion (1:1 males and females) between each season were also considered inclusion criteria. Therefore, records from 188 patients with type 2 diabetes were analyzed.

This study was conducted according to the guidelines laid down in the Declaration of Helsinki and all procedures involving patients were approved by the Hospital Ethics Committee. Written informed consent was obtained from all patients.

The new instrument: food frequency questionnaire

The most frequently consumed foods and their respective portion sizes were extracted from 3-day WDR (two nonconsecutive weekdays and one-weekend day) to create the FFQ and the food portfolio photo. All registered foods and preparation methods were listed and clustered into eight groups as proposed by the Food Guide for the Brazilian Population [13]: “cereals, tubers, roots, and derivatives”; “vegetables and legumes”; “fruits”; “beans”; “meat and eggs”; “milk and dairy products”; “oils and fats” and “sugars and sweets”. The caloric and non caloric beverages were added into a new group, according to the WDR description (“beverages group”).

Data analyses

A food item was classified according to its relative contribution, at least 80%, for daily energy or intake of a selected relevant nutrient (K nutrient) in its respective food group. The relative contribution was calculated by the equation proposed by Block et al. [14] [% K nutrient contribution by food = (amount of the K nutrient provided by food × 100) / amount of the K nutrient provided by all foods]. The most relevant nutrients in each food group were selected considering their influence on glucose metabolism [15–18] and/or diabetic complications [15, 19–22] and are described in Table 1. Information about the nutritional composition of each food and regional ingredients used in their preparation was based on NutriBase Clinical® software (1986-2013 CyberSoft, Inc. an Arizona corporation). This software used the USDA Nutrient Database for Standard Reference [23]. Nutrient data on frequently consumed foods were complemented if necessary with data obtained from local manufacturers of specific industrialized foods.

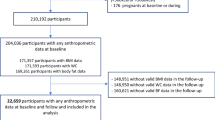

The size of servings of each food item was classified according to its respective weight distribution as registered in the WDR: small = 25th percentile, medium = 50th percentile, large = 75th percentile, and extra large = 95th percentile [24]. Figure 1 shows an example of food portions as illustrated in the food portfolio photo. The amount of each portion in grams or milliliters was transformed into household measures using the Table for Assessment of Food Intake in Household Measures [25]. The FFQ also included open questions about the frequency of food consumption and an option to include new foods according to personal eating habits. The frequency was described as the number of times the food was consumed and also if the intake occurred daily, weekly, monthly, or yearly.

In order to obtain an expert examination, the constructed FFQ was submitted to health researchers used to dealing with diabetes care: endocrinologists, nutritionists, and researchers from the GNE [10]. After the experts’ meeting, changes were made in the food list and definition of portion sizes. Regional dishes and seasonal foods were also included according to suggestions.

Portfolio with food photos

The construction of the portfolio with food photos was based on the methodology suggested by Monteiro et al. [26]. Digital photographs were taken of each portion of food from the FFQ and organized in the order in which they were mentioned, considering the four portion sizes and food groups (Figure 1). A numerical legend was also created to explain details about the each portion (amount in grams or milliliters) and keep patients blinded to serving sizes. The food portions were determined with an analytical scale (Marte ®, from 0.01 to 2000 g) and measuring cup (50-250 mL; Marinex, Brazil). The solid foods were arranged in the same plate meal size to perform the pictures, in order to help the patients acquire a perspective of size.

Results

The main features of 188 patients with type 2 diabetes were: 61.1 ± 10.1 years of age (range 34-80 years), males 50.0%, 12 years (6-18 years) of diabetes duration, BMI of 28.8 ± 4.3 kg/m2; HbA1c of 7.5 ± 1.4%, 42.5% from lower middle class, and 84.4% self-identified as whites. The patients performed 3-day WDR, totaling 564 WDR during all seasons: 25% (n = 141) in winter, 25% (n = 141) in spring, 25% (n = 141) in summer, and 25% (n = 141) in autumn.

Initially, a list of 177 different food items was compiled based on data from the WDR and the number of food items in each food cluster was as follows: “cereals, tubers, roots, and derivatives” - 39 food items; “vegetables and legumes” - 34 food items; “fruits”- 22 food items; “beans” - 5 food items; “meat and eggs” - 27 food items; “milk and dairy products” - 14 food items; “oils and fats” - 7 food items; “sugars and sweets”- 16 food items; “beverages” - 13 food items. Subsequently, only 62 food types were included in the FFQ, considering the 80% cutoff contribution in its respective food group. The reported frequency of each included food item with respective relevant nutrient is shown in Table 2. The most frequently consumed foods by patients with diabetes included white rice (94.1%), papaya (87.2%), beans (78.2%), French or Vienna bread (75.5%), banana (71.8%), and tomato (71.3%). Furthermore, another four food items (lettuce, beef, chicken, and margarine) were reported by more than 50% of this patient sample. After expert examination, 21 regional foods (fruits, vegetables, sweets, and fats), six different types of food preparations, and nine beverages were included in the food list.

The final version of the FFQ consisted of 98 food items and beverages distributed into nine groups: eight food groups and one of beverages. The preparation options (fried, boiled, cooked or roasted) were considered in food items of the “cereals, tubers, roots, and derivatives” and “meats and eggs” groups. The FFQ is shown in Additional file 1. All included food items contributed 95% of the total energy and nutrient intake as follows: total energy (94.2%), protein (96.8%), carbohydrate (92.8%), fat (94.6%), fiber (90.3%), iron (93.4%), calcium (95.3%), and potassium (92.2%). The portions of each food in grams or milliliters and its respective number of portions in household measures are shown in Table 3.

The FFQ also included open questions about frequency of food consumption and eight queries about food preferences and usual dietary practices: number of meals per day, type of sweetener added in beverages, type and amount of fat used in food preparation, if intake of visible fat from meats, the habit of salt added in prepared foods and salads, and other foods and/or seasonings not listed but regularly consumed.

Discussion

Patients with diabetes are encouraged to comply with specific dietary recommendations to achieve optimal glucose, lipid, and blood pressure control as well as a healthy body weight [2]. These aspects can modify the food intake of patients with diabetes as compared to the general population. We constructed a quantitative FFQ and a portfolio with photos of 98 food items distributed into nine food groups and based on WDR performed by patients with type 2 diabetes. This is the first FFQ for Brazilian type 2 diabetes patients.

The development of an FFQ should take into account some important aspects such as drawing up the food list, definition of portion intake [8], and how representative of the dietary habits of a population-based sample is the food list [1]. Our FFQ took into account the foods most commonly consumed by patients with type 2 diabetes and, as recommended, represents the regional dietary habits [1] in Southern Brazil. In addition, the cultural and clinical appropriateness of food items included in our FFQ was assured by using as reference the 3-day WDRs, a dietary instrument previously standardized, validated [12, 27], and widely used in diabetic patients by our research group [11, 28–30]. It is also important to keep in mind that these WDR were performed throughout the year because it is known that portion sizes and food types can vary according to season [31] and the gender distribution was equal, since gender also influences food intake [31].

The final food list was drawn up considering the contribution criteria of each relevant nutrient to minimize the omission of usually consumed food [14]. It should be noted that nutrients known to influence glucose, lipid, or blood pressure control, or that have been associated with chronic diabetic complications were considered to choose the relevant nutrients for the food list. The number of food items in the final version of the FFQ is appropriate according to suggestions found in the literature [32] and similar to other FFQs for diabetes around the world [5–7]. Small food lists (less than 50 items) may underestimate food intake, and very long lists (more than 100 items) may tire respondents and overestimate food intake [32].

The FFQ in the present study also includes a quantitative evaluation of food intake. The size of portions (quartiles of intake) was based on the weight of consumed foods assessed by 3-day WDR. These portions, specific for each food item, were shown as photos and as household measures in the food portfolio and can be easily used for respondents to select their own portion size [8]. Finally, the FFQ structure including open questions provides greater freedom to choose the actual frequency of food intake and reduces the error of consumption categories by the patients [32]. The frequency of food consumption was considered in this FFQ (day, week, month, or year). However, care should be taken when assessing the consumption of a particular food per year. The diary conversion of intake is necessary to minimize the contribution of the foods scarcely consumed in evaluating the eating habits of the individual [8].

Conclusions

In conclusion, we developed a practical quantitative FFQ and a portfolio with 98 food items covering the past 12 months and representing the usual food intake of patients with type 2 diabetes in Southern Brazil. This relatively long-term evaluation of food intake can be particularly relevant for prospective studies that evaluate associations of diet with chronic diabetic complications. However, this dietary instrument should be validated in other samples of patients.

References

Willett WC: Nutritional epidemiology. 1998, Oxford: Oxford University Press

American Diabetes Association: Standards of medical care in diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2012, 35: 11-63.

Pereira RA, Sichieri R: Métodos de avaliação do consumo alimentar. Fiocruz e Atheneu. Edited by: Kac G, Sichieri R, Gigante DP. 2007, Rio de Janeiro: Epidemiologia Nutricional, 120-200.

Riley MD, Blizzard L: Comparative validity of a food frequency questionnaire for adults with IDDM. Diabetes Care. 1995, 18 (9): 1249-1254. 10.2337/diacare.18.9.1249.

Yamaoka K, Tango T, Watanabe M, Yokotsuka M: Validity and reproducibility of a semi-quantitative food frequency questionnaire for nutritional education of patients of diabetes mellitus (FFQW65). Nihon Koshu Eisei Zasshi. 2000, 47 (3): 230-244.

Coulibaly A, Turgeon O’Brien H, Galibois I: Validation of an FFQ to assess dietary protein intake in type 2 diabetic subjects attending primary health-care services in Mali. Public Health Nutr. 2008, 12 (5): 644-650.

Hong S, et al: Development and validation of a semi-quantitative food frequency questionnaire to assess diets of Korean type 2 diabetic patients. Korean Diabetes J. 2010, 34 (1): 32-39. 10.4093/kdj.2010.34.1.32.

Cade J, Thompson R, Burley V, Warm D: Development, validation and utilization of food-frequency questionnaires – a review. Public Health Nutr. 2002, 5 (4): 567-587. 10.1079/PHN2001318.

Lopes ACS, Caiaffa WT, Mingoti SA, Lima-Costa MFF: Ingestão Alimentar em Estudos Epidemiológicos. Rev Bras Epidemiol. 2003, 6 (3): 209-219. 10.1590/S1415-790X2003000300004.

Conselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento Científico e Tecnológico: Diretório de Grupos de Pesquisa no Brasil. 2012, Grupo de Nutrição em Endocrinologia (GNE), http://dgp.cnpq.br/buscaoperacional/detalhegrupo.jsp?grupo=01924053KT5EMV#identificacao Accessed in June 26, 2012

De Paula TP, Steemburgo T, De Almeida JC, Dall'alba V, Gross JL, De Azevedo MJ: The role of Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension (DASH) diet food groups in blood pressure in type 2 diabetes. Br J Nutr. 2011, 6: 1-8.

Vaz JS, Bittencourt M, Almeida JC, Gross JL, Azevedo MJ, Zelmanovitz T: Protein intake estimated by weighed diet records in type 2 diabetic patients: misreporting and intra-individual variability using 24-hour nitrogen output as criterion standart. J Am Diet Assoc. 2008, 108 (5): 867-872. 10.1016/j.jada.2008.03.022.

Brasil. Ministério da Saúde: Secretaria de Atenção à Saúde. Departamento de Atenção Básica. Coordenação Geral da Política de Alimentação e Nutrição. Guia Alimentar para a População Brasileira. 2006, Brasília: promovendo a alimentação saudável

Block G, Dresser CM, Hartman AM, Carroll MD: Nutrient sources in the American diet: quantitative data from the NHANES II survey. Am J Epidemiol. 1985, 122: 13-26.

Bantle JP, Wylie-Rosett J, Albright AL, Apovian CM, Clark NG, Franz MJ, Hoogwerf BJ, Lichtenstein AH, Mayer-Davis E, Mooradian AD, Wheeler ML: Nutrition recommendations and interventions for diabetes: a position statement of the American Diabetes Association. Diabetes Care. 2008, 31 (Suppl. 1): S61-S78.

Pittas AG, Lau J, Hu FB, Dawson-Hughes B: The role of vitamin D and Calcium in type 2 diabetes. A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2007, 92: 2017-2029. 10.1210/jc.2007-0298.

Zillich AJ, Garg J, Basu J, Barkis GL, Carter BL: Thiazide diuretics, potassium, and the development of diabetes: a quantitative review. Hypertension. 2006, 48: 219-224. 10.1161/01.HYP.0000231552.10054.aa.

Mello VD, Laaksonen DE: Dietary fibers: current trends and health benefits in the metabolic syndrome and type 2 diabetes. Arq Bras Endocrinol Metabol. 2009, 53: 509-518. 10.1590/S0004-27302009000500004.

Robertson L, Waugh N, Robertson A: Protein restriction for diabetic renal disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2007, 17 (4): CD002181

De Mello VD, Zelmanovitz T, Perassolo MS, Azevedo MJ, Gross JL: Withdrawal of red meat from the usual diet reduces albuminuria and improves serum fatty acid profile in type 2 diabetes patients with macroalbuminuria. Am J Clin Nutr. 2006, 83 (5): 1032-1038.

De Mello VD, Zelmanovitz T, Azevedo MJ, De Paula TP, Gross JL: Long-term effect of a chicken-based diet versus enalapril on albuminuria in type 2 diabetic patients with microalbuminuria. J Ren Nutr. 2008, 18 (5): 440-447. 10.1053/j.jrn.2008.04.010.

Liu Q, Sun L, Tan Y, Wang G, Lin X, Cai L: Role of iron deficiency and overload in the pathogenesis of diabetes and diabetic complications. Curr Med Chem. 2009, 16: 113-129. 10.2174/092986709787002862.

USDA SR 17 Research Quality Nutrient Data: The Agricultural Research Service: Composition of Foods. 2006, DC, US Department of Agriculture: Agricultural Handbook no 8 Washington

Cardoso MA, Stocco PR: Desenvolvimento de um questionário quantitativo de freqüência alimentar em imigrantes japoneses e seus descendentes residentes em São Paulo. Brasil Cad Saúde Pública. 2000, 16 (1): 107-114.

Pinheiro ABV, Lacerda EMA, Benzecry EH, Gomes MCS, Costa VM: Tabela para avaliação de consumo alimentar em medidas caseiras. 3ª Ed. Rio de. 2004, Editora Atheneu: Janeiro

Monteiro JP: Nutrição e Metabolismo: Consumo Alimentar: Visualizando Porções. 1 ed. Rio de. 2007, Guanabara Koogan: Janeiro

Moulin CC, Tiskievicz F, Zelmanovitz T, De Oliveira J, Azevedo MJ, Gross JL: Use of weighed diet records in the evaluation of diets with different protein contents in patients with type 2 diabetes. Am J Clin Nutr. 1998, 67 (5): 853-857.

Almeida JC, Zelmanovitz T, Vaz JS, Steemburgo T, Perassolo MS, Gross JL, Azevedo MJ: Sources of protein and polyunsaturated fatty acids of the diet and microalbuminuria in type 2 diabetes mellitus. J Am Coll Nutr. 2008, 27 (5): 528-537. 10.1080/07315724.2008.10719735.

Steemburgo T, Dall'Alba V, Almeida JC, Zelmanovitz T, Gross JL, De Azevedo MJ: Intake of soluble fibers has a protective role for the presence of metabolic syndrome in patients with type 2 diabetes. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2009, 63 (1): 127-133. 10.1038/sj.ejcn.1602902.

Silva FM, Steemburgo T, De Mello VD, Tonding SF, Gross JL, Azevedo MJ: High dietary glycemic index and low fiber content are associated with metabolic syndrome in patients with type 2 diabetes. J Am Coll Nutr. 2011, 30 (2): 141-148. 10.1080/07315724.2011.10719953.

Slater B, Philippi ST, Marchioni DML, Fisberg RM: Validação de Questionários de Freqüência Alimentar - QFA: considerações metodológicas. Rev Bras Epidemiol. 2003, 6 (3): 200-208. 10.1590/S1415-790X2003000300003.

Fisberg RM, Slater B, Marchioni DML, Martini LA: Inquéritos Alimentares: métodos e bases científicos. 2005, São Paulo: Manole

Pre-publication history

The pre-publication history for this paper can be accessed here:http://www.biomedcentral.com/1471-2458/13/740/prepub

Acknowledgments

This study was partially supported by Fundo de Incentivo à Pesquisa e Eventos – Hospital de Clínicas de Porto Alegre and Fundação de Amparo à Pesquisa do Estado do Rio Grande do Sul (ARD-FAPERGS 01/2010). RAS received scholarships from Fundação de Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal de Nível Superior (CAPES), and BPR from Programa Institucional de Bolsas de Iniciação Científica - Conselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento Científico e Tecnológico.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

RAS was responsible for the study design, collection, analysis and interpretation of data, as well as the preparation of the manuscript. BPR contributed the construction of the portfolio with food photos. TCR contributed the initial idea. MJA contributed to the interpretation of results and final version of the manuscript. JCA contributed to the study design and each step of the FFQ construction as well as proof-reading the manuscript. The final paper version was approved by all authors.

Electronic supplementary material

Authors’ original submitted files for images

Below are the links to the authors’ original submitted files for images.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is published under license to BioMed Central Ltd. This is an Open Access article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License ( https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0 ), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

About this article

Cite this article

Sarmento, R.A., Riboldi, B.P., da Costa Rodrigues, T. et al. Development of a quantitative food frequency questionnaire for Brazilian patients with type 2 diabetes. BMC Public Health 13, 740 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-13-740

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-13-740